b Department of Chemistry, Stoddart Institute of Molecular Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China;

c Green Catalysis Center and College of Chemistry, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, China

In natural muscular tissues, fueled by ATP, myosin motors pull on actin filaments and collectively reduce the micrometric size of a sarcomere unit [1]. Both hierarchical organization of sarcomeres in myofibrils and subsequent bundling of the myofibrils in stiffer muscular fibers lead to macroscopic actuations. To mimic these efficient motions in biological systems, chemists have now succeeded in building a number of molecular muscles. One of the most prolific lines of investigations concerns the supramolecular control over the molecular topology and the mechanical bond of interlocked molecules to realize the internal motions of large amplitudes [2-7].

Many molecular muscles based on catenanes and rotaxanes have been reported with programmed intramolecular switching when stimulated by external triggers [8-14]. In particular, caused by the well-defined intramolecular sliding actuations, [c2]daisy chain rotaxanes have been widely applied in this field [15-18], which is a cyclic dimer has two subcomponents made of one cycle and one axle, with each axle threading the other cycle. Since the first bistable [c2]daisy chain rotaxane prepared by Sauvage and co-workers in 2000 [19], molecular muscles with doubly threaded structures based on different cyclic moieties have been developed rapidly. For instance, not only the synthetic macrocycles, such as crown ethers [20-28], cyclodextrins [29-31], nanohoops [32], cyclobis(paraquat-p-phenylene) [33-35], and cyclic polymetallic complexes [36,37], but also bio-originated cyclic-peptides [38] and cyclic-DNAs [39], have been used extensively as the cycle part. However, all these reported [c2]daisy chains were formed by two exactly the same non-chiral (crown ethers, cyclobis(paraquat-p-phenylene), cyclic polymetallic complexes) or single-chiral (cyclodextrins) subcomponents. In contrast, we reported here, an interlock-induced meso-molecular muscle made up of two copillar[5]arene moieties with opposite planar chirality (a pR and a pS).

Pillararene is a new class of macrocycles composed of hydroquinone units linked by methylene bridges at para positions [40-54]. Different from traditional macrocycles, they all have two most stable conformations (pR and pS) that are mirror images of each other (Fig. S1 in Supporting information) [55-60]. By one pot cyclic co-oligomerization of different monomers, mono-, di- even tetra-functionalized copillar[5]arene have been prepared and applied as building blocks in the construction of various supramolecular systems [61-68]. Because of the selective binding of a pillar[5]arene cavity to a linear alkyl chain, mono-functionalized copillar[5]arene became one of the most-accessible model for construction of daisy chains [69-77]. Especially, when an electron withdrawing group was introduced at the terminal of the guest part, [c2]daisy chains could be easily formed by the selective self-assembly process. Interestingly, as reported by Liu et al. [71], Wang et al. [72] and us [69,77], from their crystal structures, we observed that most of such [c2]daisy chains were composed of two copillar[5]arene molecules with opposite planar chirality conformations, as shown in Figs. S2–S7 (Supporting information). Therefore, we believed that if we could cap such a cyclic dimer with a suitable stopper, a doubly interlock-induced meso-molecular muscle would be prepared.

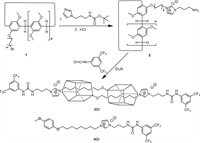

To verify this deduction, a bistable molecular muscle 3Cl was synthesized in two steps from a bromo-functionalized copillar[5]arene 1, which was synthesized by co-oligomerization of 1, 4-dimethoxybenzene and 1-(8-bromooctyloxy)-4-methoxybenzene [61,69], as shown in Scheme 1. An imidazole group was introduced by refluxing 1 with tert-butyl(3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)propyl)carbamate in acetonitrile. The terminal amino was released by the following deprotection of Boc-group using hydrochloric acid. The monomer 2 was then self-assembled and capped by 3, 5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl isocyanate with excess triethylamine in chloroform at room temperature. After purification by column chromatography, the main product 3Cl was isolated in 45% yield. Using the same method, a control compound 4Cl without the pillar[5]arene cavity was prepared (Scheme 1 and Scheme S1 in Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Synthesis of the meso-molecular-muscle 3Cl and control compound 4Cl. | |

Evidence for the formation of the desired doubly interlocked [c2]daisy chain type molecular muscle was firstly obtained by the electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) studies. Different from the mass (Fig. S10 in Supporting information) of [2–Cl]+ (m/z 972.54), for 3Cl, peaks were observed corresponding to [3Cl–2Cl]2+ (m/z 1228.06), with the intervals were only 0.5 instead of 1 as shown in Fig. 1. These results were all isotopically resolved and in excellent agreement with their theoretical distributions.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. ESI mass spectrum of 3Cl (blue) and its simulated spectrum (red). | |

Single crystals of 3Cl were obtained by slow evaporation of a solution of 3Cl in a chloroform/methanol mixture (CCDC: 2257323). The X-ray crystallographic analysis (Fig. 2) revealed that, as we expected, a doubly interlocked molecular muscle 3Cl was formed by two mirror image subcomponents (a pR-copillar[5]arene shown in blue and a pS-copillar[5]arene). In this cyclic dimer, the octyl group of each half threaded through the electron-rich cavity of the other half, leaving the imidazolium, propylidene and urea groups at the outer side. There were four hydrogen atoms on each of the included linear octyl group with C—H···π plane distances (A, 2.983; B, 2.872 C, 2.729; D, 2.601) shorter than 3.05 Å, implying the existence of multiple C—H···π interactions (green dotted lines in Fig. 2). This is similar to the cases for the previously reported mono-substituted copillar[5]arenes in the solid state [59,67,69,70,75]. Additionally, one C—H···π interaction (E, 2.517 Å) and one C—H···O interaction (F, 2.352 Å, 165°) between the electron-poor imidazolium and the electron-rich pillar[5]arene cavity were observed, which also should be the driven force of the contraction of 3Cl in the solid state. Moreover, there are two N—H···Cl interactions (G, 2.609 Å, 152°; H, 2.363 Å, 167°) between the urea group and the chloride ion on each half of the molecular muscle. The crystal structure of 3Cl clearly showed that, indeed, it is a meso-[c2]daisy chain type molecular muscle composed of a pR-copillar[5]arene and a pS-copillar[5]arene, whose conformations were fixed by the doubly interlocked mechanical bonds.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Stick presentations of 3Cl in the solid state. Hydrogens, except the ones with CH-π, CH—O or NH—Cl interactions, were omitted for clarity. The pR-conformation was shown as blue sticks. Lines A–E indicate the multiple CH···π interactions. Line F–H indicates the CH···O or NH···Cl interactions. Parameters: C—H···π distance (Å), A, 2.983; B, 2.872 C, 2.729; D, 2.601; E, 2.517. CH···O distance (Å), CH—O angle (°): F, 2.352,165. NH···Cl distance (Å), NH···Cl angle (°): G, 2.609,152, H, 2.363,167. | |

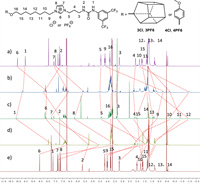

The internal motions of this meso-molecular muscle were systematically investigated by NMR spectra afterwards. The proton NMR spectrum of 3Cl (Fig. 2b and Fig. S11 in Supporting information) in chloroform-d showed that, like other host-guest complex of pillar[5]arenes and linear alkyl groups, there were also several broad peaks located in the high field, two peaks were even below zero. Therefore, 3Cl should be a doubly threaded cyclic dimer with the linear guest moieties threaded in the aromatic pillar[5]arene cavities. Moreover, from 2D 1H–1H COSY experiments of 3Cl (Fig. S12 in Supporting information) and 4Cl (Fig. S25 in Supporting information) in chloroform-d, the signals from the linear guest protons were identified, respectively. By comparison of 1H NMR spectra of them (Figs. 2a and b), the chemical shift changes of the guest protons caused by threading through the electron-rich copillar[5]arene cavity can be estimated. The protons H6, H8, H9 and H10 on the guest moiety showed much larger upfield chemical shift changes (–1.9, –1.9, –3.9 and –3.3 ppm, respectively) than others (as indicated by the red dotted lines in Fig. 3). These results proved that, same as its solid state structure shown in Fig. 2, in chloroform-d, the center of pillar[5]arene cavities were located on H9 and H10 of the octyl group. To clarify the influence of different solvents to the meso-molecular muscle, we performed the 1H NMR and 2D 1H–1H COSY (Fig. S14 in Supporting information) experiments of 3Cl in deuterated DMSO. By the comparison of Figs. 2a–c, we found that H12 and H11 showed the largest upfield chemical shift changes (‒2.2 and ‒2.6 ppm, respectively). It indicated that, in the polar solvent DMSO, the meso-molecular muscle is somehow extended, with the center of pillar[5]arene cavities located on H12 and H11 of the linear octyl group.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Partial 1H NMR (500 MHz, 25 ℃) spectra: (a) 4Cl in CDCl3; (b) 3Cl in CDCl3; (c) 3Cl in DMSO-d6; (d) 3PF6 in CDCl3; (e) 4PF6 in CDCl3. | |

The impact of the counter ions was studied subsequently. By mixing with the saturated solution of potassium hexafluorophosphate respectively, the meso-molecular muscle 3PF6 and the control compound 4PF6 were prepared (Scheme S1). From the 2D 1H–1H COSY NMR spectrum of 3PF6 (Fig. S17 in Supporting information) and 4PF6 (Fig. S29 in Supporting information) in chloroform-d, we assigned all the signals of the linear guest protons respectively. By comparison of 1H NMR spectra of them (Figs. 2d and e), we found that the upfield chemical shifts of protons on the guest moiety were averaged on some extent, and no peaks below 0 ppm could be found for the 3PF6. Caused by the loose ion pairing of hexafluorophosphate, H5, H6, H7, H8 and H9 on the guest moiety showed relatively larger upfield chemical shift changes (–2.7, –1.7, –2.7, –3.5 and –1.9 ppm, respectively), which proved that the center of pillar[5]arene cavities should located on the electron-poor imidazolium group at these conditions. Therefore, at this time, we can conclude that the meso-molecular muscle was in a fully contracted state.

In summary, here we successfully prepared a molecular muscle 3Cl by capping the [c2]daisy chain dimer of a mono-functionalized copillar[5]arene 2 with an imidazolium group in its axle. From its crystal structure, we observed that 3Cl was a cyclic dimer composed of two mirror image subcomponents a pR- and a pS-copillar[5]arene. Their conformations were fixed by the doubly interlocked mechanical bond. Therefore, we named 3Cl as an interlocked induced meso-molecular muscle. By comparison of 1H NMR, COSY spectra of 3Cl, 4Cl, 3PF6 and 4PF6, its internal motions were investigated. It demonstrated that the length of this molecular muscle could be controlled not only by changing the solvents, but also by changing the counter anions. In DMSO, the molecular muscle was in an extended state with the cavity center on H12 and H11. In chloroform, the molecular muscle was in a partially contracted state with the cavity center on H9 and H10 of the linear octyl group. When the chloride anions were replaced by hexafluorophosphates, it will be in a fully contracted state with the cavity center located on the imidazolium groups. Applying such copillar[5]arene monomers in the construction of stimuli-responsive mechanically interlocked polymers or molecular actuators that can mimic the biologic contraction/stretching process in natural muscular tissues is another goal.

Declaration of competing interestsThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsZ. Zhang thanks the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LY22B040001) and the Science & Technology Innovation Program of Zhejiang Province (No. 2018R52051). F. Huang thanks the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22035006) for financial support. The authors thank Jiyong Liu (Department of Chemistry, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China) for the single crystal characterization.

AcknowledgmentsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108712.

| [1] |

J.L. Krans, Nat. Educ. 3 (2010) 66-69. |

| [2] |

J.P. Sauvage, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 11080-11093. DOI:10.1002/anie.201702992 |

| [3] |

J.F. Stoddart, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 11094-11125. DOI:10.1002/anie.201703216 |

| [4] |

B.L. Feringa, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 11060-11078. DOI:10.1002/anie.201702979 |

| [5] |

D.A. Leigh, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 14506-14508. DOI:10.1002/anie.201609841 |

| [6] |

S.D.P. Fielden, D.A. Leigh, S.L. Woltering, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 11166-11194. DOI:10.1002/anie.201702531 |

| [7] |

J.R. Nitschke, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 39. DOI:10.1002/anie.201611682 |

| [8] |

S.E. Cakmak, D.A. Leigh, C.T. McTernan, A.L. Nussbaumer, Chem. Rev. 115 (2015) 10081-10206. |

| [9] |

C.J. Bruns, J.F. Stoddart, Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 2186-2199. DOI:10.1021/ar500138u |

| [10] |

M. Baroncini, S. Silvi, A. Silvi, Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 200-268. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00291 |

| [11] |

D. Dattler, G. Fuks, J. Heiser, et al., Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 310-433. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00288 |

| [12] |

L.F. Hart, J.E. Hertzog, P.M. Rauscher, et al., Nat. Rev. Mater. 6 (2021) 508-530. DOI:10.1038/s41578-021-00278-z |

| [13] |

X. Wang, W. Li, W. Wang, H. Yang, Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 4091-4106. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00507 |

| [14] |

D. Xia, P. Wang, X. Ji, et al., Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 6070-6123. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00839 |

| [15] |

J. Rotzler, M. Mayor, Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2013) 44-46. DOI:10.1039/C2CS35217F |

| [16] |

A. Goujon, E. Moulin, G. Fuks, N. Giuseppone, CCS Chem. 1 (2019) 83-96. DOI:10.31635/ccschem.019.20180023 |

| [17] |

X. Wang, W. Li, W. Wang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 13923-13930. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b06739 |

| [18] |

M. Xue, Y. Yang, X. Chi, X. Yan, F. Huang, Chem. Rev. 115 (2015) 7398-7501. DOI:10.1021/cr5005869 |

| [19] |

M.C. Jiménez, C.D. Buchecker, J.P. Sauvage, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39 (2000) 3284-3287. DOI:10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3284::AID-ANIE3284>3.0.CO;2-7 |

| [20] |

L. Fang, M. Hmadeh, J. Wu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (2009) 7126-7134. DOI:10.1021/ja900859d |

| [21] |

B. Zheng, M. Zhang, S. Dong, J. Liu, F. Huang, Org. Lett. 14 (2012) 306-309. DOI:10.1021/ol203062w |

| [22] |

X. Fu, Q. Zhang, S. Rao, D. Qu, H. Tian, Chem. Sci. 7 (2016) 1696. DOI:10.1039/C5SC04844C |

| [23] |

A. Goujon, G. Mariani, T. Lang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 4923-4928. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b00983 |

| [24] |

D. Aoki, G. Aibara, S. Uchida, T. Takata, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 6791-6794. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b01151 |

| [25] |

A. Goujon, T. Lang, G. Mariani, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 14825-14828. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b06710 |

| [26] |

J. Chang, S. Tseng, C. Lai, et al., Nat. Chem. 9 (2017) 128-134. DOI:10.1038/nchem.2608 |

| [27] |

P.Q. Nhien, J.H. Tien, T.M. Khang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. C 10 (2022) 18241-18257. DOI:10.1039/d2tc03814e |

| [28] |

Z. Zhang, W. You, P. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 567-578. DOI:10.1021/jacs.2c11105 |

| [29] |

S. Ikejiri, Y. Takashima, M. Osaki, H. Yamaguchi, A. Harada, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 17308-17315. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b11351 |

| [30] |

L. Randone, H. Onagi, S.F. Lincoln, C.J. Easton, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019 (2019) 3495-3502. DOI:10.1002/ejoc.201900136 |

| [31] |

S. Tsuda, Y. Komai, S.I. Fujiwara, Y. Nishiyama, Chem. Eur. J. 27 (2021) 1966-1969. DOI:10.1002/chem.202004505 |

| [32] |

J.M. Van Raden, N.N. Jarenwattananon, L.N. Zakharov, R. Jasti, Chem. Eur. J. 26 (2020) 10205-10209. DOI:10.1002/chem.202001389 |

| [33] |

D. Cao, C. Wang, M.A. Giesener, Z. Liu, J.F. Stoddart, Chem. Commun. 48 (2012) 6791-6793. DOI:10.1039/c2cc32499g |

| [34] |

C.J. Bruns, M. Frasconi, J. Iehl, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 4714-4723. DOI:10.1021/ja500675y |

| [35] |

K. Cai, Y. Shi, G. Zhuang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 10308-10313. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c04029 |

| [36] |

A. Fernandez, E.M. Pineda, J.F. Soria, et al., Chem. Commun. 51 (2015) 11126-11129. DOI:10.1039/C5CC02216A |

| [37] |

J.F. Soria, A. Fernandez, D. Asthana, et al., Chem. Commun. 55 (2019) 2960-2963. DOI:10.1039/C8CC09339C |

| [38] |

H.V. Schröder, Y. Zhang, A.J. Link, Nat. Chem. 13 (2021) 850-857. DOI:10.1038/s41557-021-00770-7 |

| [39] |

S. Yao, Y. Chang, Z. Zhai, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022) 20739-20748. DOI:10.1021/acsami.2c03265 |

| [40] |

T. Ogoshi, S. Kanai, S. Fujinami, T.A. Yamagishi, Y. Nakamoto, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (2008) 5022-5023. DOI:10.1021/ja711260m |

| [41] |

Y.Kou D.Cao, J. Liang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48 (2009) 9721-9723. DOI:10.1002/anie.200904765 |

| [42] |

P.J. Cragg, K. Sharma, Chem. Soc. Rev. 41 (2012) 597-607. DOI:10.1039/C1CS15164A |

| [43] |

G. Yu, C. Han, Z. Zhang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134 (2012) 8711-8717. DOI:10.1021/ja302998q |

| [44] |

M. Xue, Y. Yong, X. Chi, Z. Zhang, F. Huang, Acc. Chem. Res. 45 (2012) 1294-1308. DOI:10.1021/ar2003418 |

| [45] |

Q. Duan, Y. Cao, Y. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 10542-10549. DOI:10.1021/ja405014r |

| [46] |

Z. Li, Y. Zhang, C. Zhang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 8577-8589. DOI:10.1021/ja413047r |

| [47] |

N.L. Strutt, H. Zhang, S.T. Schneebeli, J.F. Stoddart, Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 2631-2642. DOI:10.1021/ar500177d |

| [48] |

C. Li, Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 12420-12433. DOI:10.1039/C4CC03170A |

| [49] |

K. Wang, C. Wang, Y. Zhang, et al., Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 9458-9461. DOI:10.1039/C4CC03992K |

| [50] |

Z. Zhang, K. Sun, S. Li, G. Yu, Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 956-960. |

| [51] |

X. Lou, Y. Yang, Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) 2003263. DOI:10.1002/adma.202003263 |

| [52] |

Y. Cai, Z. Zhang, Y. Ding, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 1267-1279. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.10.036 |

| [53] |

H. Zhang, K. Huang, L. Ding, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1537-1540. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.002 |

| [54] |

Y. Li, X. Lou, C. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107877. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.107877 |

| [55] |

T. Ogoshi, K. Masaki, R. Shiga, K. Kitajima, T.A. Yamagishi, Org. Lett. 13 (2011) 1264-1266. DOI:10.1021/ol200062j |

| [56] |

J. Yao, W. Wu, W. Liang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 6869-6873. DOI:10.1002/anie.201702542 |

| [57] |

E.J. Lee, H.Y. Ju, I.H. Park, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 9669-9677. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b05751 |

| [58] |

S. Li, H. Zhang, X. Xu, Y. Liu, Nat. Commun. 6 (2015) 7590. DOI:10.1038/ncomms8590 |

| [59] |

H. Liang, B. Hua, F. Xu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 19772-19778. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c10570 |

| [60] |

H. Zhu, Q. Li, B. Shi, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 17340-17345. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c09598 |

| [61] |

Z. Zhang, B. Xia, C. Han, Y. Yu, F. Huang, Org. Lett. 12 (2010) 3285-3287. DOI:10.1021/ol100883k |

| [62] |

L. Liu, D. Cao, Y. Jin, et al., Org. Biomol. Chem. 9 (2011) 7007-7010. DOI:10.1039/c1ob05871a |

| [63] |

K. Wang, L. Tan, D. Chen, et al., Org. Biomol. Chem. 10 (2012) 9405-9409. DOI:10.1039/c2ob26635k |

| [64] |

Y. Zhang, B. Shi, H. Li, et al., Polym. Chem. 5 (2014) 4722-4725. DOI:10.1039/C4PY00186A |

| [65] |

P. Wei, D. Li, B. Shi, Q. Wang, F. Huang, Chem. Commun. 51 (2015) 15169-15172. DOI:10.1039/C5CC06682D |

| [66] |

M. Wu, Y. Yang, Polym. Chem. 10 (2019) 2980-2985. DOI:10.1039/c8py01497c |

| [67] |

X. Lou, Y. Yang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 11976-11981. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c07006 |

| [68] |

S. Liu, T. Yan, Q. Wu, Z. Xu, J. Han, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 239-242. DOI:10.3390/land11020239 |

| [69] |

Z. Zhang, G. Yu, C. Han, et al., Org. Lett. 13 (2011) 4818-4821. DOI:10.1021/ol2018938 |

| [70] |

Z. Zhang, C. Han, G. Yu, F. Huang, Chem. Sci. 3 (2012) 3026-3031. DOI:10.1039/c2sc20728a |

| [71] |

L. Liu, L. Wang, C. Liu, et al., J. Org. Chem. 77 (2012) 9413-9417. DOI:10.1021/jo301779y |

| [72] |

X. Wang, K. Han, J. Li, X. Jia, C. Li, Polym. Chem. 4 (2013) 3998-4003. DOI:10.1039/c3py00462g |

| [73] |

Y. Han, G. Huo, J. Sun, et al., Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 28748. DOI:10.1038/srep28748 |

| [74] |

S. Jiang, Y. Han, J. Sun, C. Yan, Tetrahedron 73 (2017) 5107-5114. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2017.07.001 |

| [75] |

R. Zhang, C. Wang, R. Long, et al., Front. Chem. 7 (2019) 508. DOI:10.3389/fchem.2019.00508 |

| [76] |

W. Li, W. Wang, X. Wang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 8473-8482. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c02475 |

| [77] |

Y. Yao, J. Liu, P. Zhang, et al., Cryst. Growth Des. 23 (2023) 68-76. DOI:10.1021/acs.cgd.2c00711 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35