Adenine is one of the two purine nucleobases serving as a main building block for a range of endogenous compounds that play essential roles in many cellular processes [1], for example, as a key structural component in adenosine and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) involved in cell signalling and the well-known biological energy-carrying molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP). A large number of proteins bind adenine-containing ligands or cofactors [2], such as protein kinases, ATPases, and other adenosine nucleotide-binding proteins [3], which are pivotal to cell signalling and protein regulation.

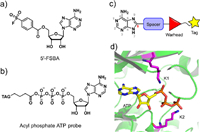

In recent years, a variety of affinity-based probes have been developed to covalently label specific amino acids within the binding sites of proteins. Lysine residues are more abundant (5.9% of all residues in human proteins) than cysteine residues (1.9% of all residues) [4,5], a number of chemical probes targeting lysine residues have been developed [6–11]. There are two notable examples of compounds with an adenosine moiety that covalently bind a lysine residue, 5′-fluorosulfonylbenzoyl 5′-adenosine (5′-FSBA) (Fig. 1a) [12–17] and an acyl phosphate ATP probe [18,19] (Fig. 1b). Even though the acyl phosphate probe is able to label a wide range of kinases and other nucleotide-binding proteins, unfortunately, its intrinsic chemical and physicochemical properties restrict it to applications in cell lysates. Development of cell-permeable probes for interrogating nucleotide-binding proteins in living cells is therefore much needed. Here we present our efforts in developing adenine-based probes with activated ester reactive groups that successfully label and capture a number of nucleotide-binding proteins in living cells.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Design strategy of an adenine-derived probe. (a, b) Chemical structure of 5′-FSBA and acyl phosphate ATP probe. (c) Framework of modular-designed probe based on a study of the co-crystal structure of kinase complexed with ATP. (d) Study of ATP and conserved lysine residues within the co-crystal structure of kinase (PDB ID: 1HCK). | |

A modular approach, combined with structure-based design, was adopted in order to construct this series of cell-permeable probes (Fig. 1). We started with adenine as the main recognition motif of probes, which not only avoids the cell permeability issue caused by the ribose and charged phosphate moieties of ATP but also is capable of being recognized by a wider range of nucleotide-binding proteins beyond protein kinases. The general design of our probes included adenine, a spacer, a reactive group, and a tag moiety for purification (Fig. 1c).

Considering that protein kinases are a distinctive enzyme family among the nucleotide-binding proteome and have been extensively studied, we used protein kinases as a template. For a general probe, we looked for conserved nucleophilic amino acids in the ATP binding pocket. Sequence comparisons have shown that virtually all kinases have two conserved lysine residues within their active sites [20]. The first lysine residue is conserved in all typical protein kinases, with few exceptions [3,21], and the second lysine residue is conserved in the majority of serine/threonine kinases. Unlike the ε-amine of surface lysines, these internal lysines at the active site were amenable to modification by covalent small molecules due to their lower pKa's than surface lysines [22,23]. A total of 120 available co-crystal structures of kinase–ATP complexes were examined (Table S1 in Supporting information), which showed that the phosphate group of the ATP was positioned in a direct line with the C-8 carbon atom of adenine, thus directly connecting a spacer moiety out of the C-8 atom seemed like a tempting approach (Figs. 1c and d). By measuring the distance between the terminal nitrogen atoms of the two conserved lysine residues and the respective phosphorus atoms of the terminal phosphate groups, we also found that the first lysine residue was closer to the α-phosphate, with an average distance of 3.90 Å, while the second lysine residue was closer to the γ-phosphate of ATP, with an average distance of 5.09 Å (Fig. S1 and Table S1 in Supporting information). Thus, a benzene ring was considered as the spacing block because of its appropriate size and the possibility of fine-tuning the reactivity of reactive groups by decorating substituents on the benzene ring. The meta-position of the benzene ring would be proximal to the ε-amino groups of lysines. We chose the ester group as the reactive group to transfer an alkynyl tag onto proteins in order to facilitate subsequent detection and purification. Consequently, compounds 6a–6h were designed and synthesized (Fig. 2a and Scheme S1 in Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Labelling studies of probe 6f in vitro. (a) Chemical structures of adenine-derived probes 6a–6h (b) Adenine probe labelling of recombinant Btk protein (0.4 µg each lane) showing fluorescence scanning (FS) and silver staining (SS). (c) Concentration course of labelling of recombinant Btk protein (0.4 µg each lane) by probe 6f. (d) Time course of labelling of recombinant Btk protein (0.4 µg each lane) by probe 6f (50 µmol/L). (e) Probe 6f was able to label multiple purified kinases. Fluorescence scanning (FS, upper) and silver staining (SS, lower). | |

We first examined whether these six probes could covalently label recombinant kinases. Recombinant Btk (0.4 µg) was incubated with these six probes (100 µmol/L) separately, followed by click reaction with tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA)-azide for 1 h. After boiling with loading buffer, the mixture was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then in-gel fluorescence scanning. The results revealed that all six probes labelled Btk, of which probe 6f exhibited the strongest fluorescence intensity of the protein bands (Fig. 2b). We first studied the stability of probe 6f in aqueous solution by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. The results showed that it's half-life in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) buffer is ~68.5 h (Fig. S2 in Supporting information). Then probe 6f was selected for subsequent examination.

The gel image showed that the fluorescence signals intensified when increasing concentrations of probe 6f were incubated with the same amount of recombinant Btk, and maximum Btk labelling was achieved at approximately 50 µmol/L probe 6f (Fig. 2c). When probe 6f was incubated with Btk for increasing incubation times, the brightness of the fluorescence signals indicated that probe 6f efficiently labelled Btk within 15 min, suggesting the excellent labelling efficiency of our probe (Fig. 2d). A variety of kinases (Btk, Lck, Jak3, Tak1, CDK2, Gsk3β, CDK1, Mek1, and Erk2) were examined for general kinase labelling. The results clearly demonstrated that probe 6f displayed appreciable labelling for most of the kinases tested (Fig. 2e).

Next, we tried to identify the exact labelling sites of probe 6f. Purified Btk, Lck, and CDK1 were used as model kinases. After incubating probe 6f (6 µmol/L) with purified kinases (2 µmol/L) for 1 h, the mixture was digested with trypsin and subjected to analysis by LC-MS/MS. Mass spectrometry data showed that the peptide 423GQYDVAIKMIK433 of Btk was found to be covalently modified and exhibited a mass increase of 80.03 Da when compared to the unmodified peptide, which exactly matched the mass change due to the amide formed by the ε-amine of lysine and the carbonyl group of the probe. LC-MS/MS data further revealed that Lys-430 (Btk) was indeed the amino acid modified by probe 6f (Fig. 3a). Similarly, the peptide 270VAVKSLK276 of Lck was detected to be labelled at Lys-273 (Fig. S3 in Supporting information), and the peptides 25TTGQVVAMKK34 and 128DLKPQNLLIDDK139 of CDK1 were also detected to be labelled at Lys-33 and Lys-130, respectively (Fig. S4 in Supporting information). As expected, all modified amino acids described above were the conserved lysine residues within the corresponding kinases. Taken together, these results demonstrated that probe 6f was able to covalently bind to the conserved lysine residues in the ATP binding site of protein kinases and form a stable amide bond (Fig. 3b). We further docked probe 6f into the ATP binding pocket of Btk in order to visualize the binding mode. The calculation predicts that probe 6f can occupy the pocket with a similar binding mode as that of ATP. The amino group of probe 6f may form hydrogen bonds with Glu-475 and Met-477 of Btk, and the carbonyl group of probe 6f sits very close to the ε-amine of the conserved lysine residue, making it possible to form an amide bond (Figs. 3c and d).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. LC-MS/MS analysis of exact modified site of probe 6f. (a) Peptide fragmentation data of Btk/probe 6f adduct reveals that lysine-430 is the binding site of probe 6f. (b) Proposed mechanism of labelling. The ε-amine of the conserved lysine attacks the carbonyl carbon of the probe to form a stable amide bond, releasing an adenine motif. (c) Putative binding mode of probe 6f in the Btk kinase domain. (d) Probe 6f interaction diagram (2D representation) by MOE (PDB ID: 3GEN). | |

We then proceeded to address the critical question of whether our probe could be applied to labelling endogenous proteins in living cells. A concentration course study of labelling for human B-cell lymphoma OCI-LY7 cells showed that 50 µmol/L probe 6f displayed appreciable labelling (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). Cell-based inhibition assay showed that probe 6f had a low inhibitory effect on OCI-LY7 cell growth (GI50 > 50 µmol/L, Fig. S6 in Supporting information). All of these six probes (6a-6f, 50 µmol/L) were incubated with OCI-LY7 cells at 37 ℃ for 0.5 h, and then lysates were prepared and subjected to click conjugation with TAMRA-azide for 1 h. All of the probes labelled different levels of proteins, with no detection in the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) group (Fig. 4a), while probe 6f displayed the strongest overall labelling intensity, consistent with the labelling results with recombinant proteins. Pre-incubation of 6g, an inhibitor without an alkyne group, reduced the fluorescence signals (Fig. 4b).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Labelling studies of probe 6f in vivo. (a) Gel-based profiling of adenine probe 6a-6f labelled in OCI-LY7 cell line. Fluorescence scanning (TAMRA, upper) and Coomassie Blue staining (CBB, lower). (b) Fluorescence scanning of SDS-PAGE gel resolving proteins labelled by probe 6f in the presence of increasing concentrations of compound 6g. (c) Gel-based profiling of probe 6f and 6h labelled in OCI-LY7 cell line. (d) Silver staining analysis of pull-down enrichment in OCI-LY7 cell line by probe 6f and control. (e) Representative protein hits identified by pull-down/LC−MS/MS with probe 6f (50 µmol/L), the full details see Tables S2-S5 in Supporting information. (f) Target validation by pull-down/Western blot (WB) with probe 6f and the corresponding antibodies in OCI-LY7 cell line. Whole cell lysate (WCL). | |

We further profiled the probe 6f-labelling proteome in an intracellular context. Compound 6h was synthesized as a negative control, which was otherwise identical to 6f, except for using an amide group instead of the ester group. As expected, gel-based profiling showed that compound 6h did not significantly label any proteins (Fig. 4c). The probe 6f-labelled cellular samples were subjected to a ‘click reaction’ with biotin-PEG3-ethyl-azide and then enriched and purified with streptavidin sepharose beads. After boiling, the captured proteins on beads were eluted into loading buffer, followed by SDS-PAGE. Silver staining analysis showed that probe 6f labelled a number of proteins in living cells (Fig. 4d), including endogenous Btk and Lck kinase (Figs. 4e and f).

In order to identify the probe-labelled proteins, a label-free MS quantification was adopted in order to identify labelled proteins with three independent replicates. According to the literature [12,24,25], we used criteria of unique peptides ≥ 1 and a fold change (probe 6f/6h or DMSO) > 2; probe 6f captured 52 kinases in both data sets (Tables S2 and S3 in Supporting information). Using criteria of P-value < 0.05 and fold change > 2, probe 6f captured 581 proteins, compared to the DMSO group (Table S4 and Fig. S7a in Supporting information) and 592 proteins, compared to the probe 6h group (Table S5 and Fig. S7b in Supporting information). An analysis of these identified proteins was conducted based on their function or nucleotide-binding ability, and the results are summarized in Fig. 4e and Fig. S8 (Supporting information). Of these proteins, a significant proportion were adenine moiety-recognizing proteins, including nucleotide-binding proteins (33%) and DNA/RNA-binding proteins (30%). In addition, there were approximately 1% of nucleotide biosynthetic enzymes, GTPase, as well as GTP-binding proteins. Clearly, these proteins had adenine-containing ligand-binding ability and could be labelled by our adenine-derived probe. Finally, we further validated the important targets protein hits including kinase such as Btk, Syk, MAPK1 (Erk2), Blk and Lck, as well as HSP90AB1, MCM3, PFKM nucleotide binding proteins by pull-down/Western blot with probe 6f and the corresponding antibodies (Fig. 4f), these immunoblotting results were also consistent with probe 6f pull-down/LC−MS/MS experiments. Overall, the adenine-based probe 6f was capable of identifying numerous endogenous nucleotide-binding proteins in living cells.

In summary, we have developed a novel adenine-based probe 6f to covalently capture a number of endogenously expressed kinases and diverse nucleotide-binding proteins in living cells. A global study of nucleotide-binding proteins is very challenging owing to the enormous diversity of the nucleotide-binding protein family. With additional modifications of the adenine moiety, more potent or selective probes may be developed to capture proteins within complex cellular contexts. Nevertheless, our probe clearly provides a new starting point for probing the nucleotide-binding proteome.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsWe acknowledge funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81872749), Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (Nos. 20200815000631001 and JCYJ20200109120414564), and Peking University.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108455.

| [1] |

R. Shapiro, Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 25 (1995) 83-98. DOI:10.1007/BF01581575 |

| [2] |

B.F. Cravatt, A.T. Wright, J.W. Kozarich, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77 (2008) 383-414. DOI:10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.124125 |

| [3] |

G. Manning, D.B. Whyte, R. Martinez, et al., Science 298 (2002) 1912-1934. DOI:10.1126/science.1075762 |

| [4] |

M.A. Gauthier, H.A. Klok, Chem. Commun. (2008) 2591-2611. DOI:10.1039/b719689j |

| [5] |

C.B. Rosen, M.B. Francis, Nat. Chem. Biol. 13 (2017) 697-705. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.2416 |

| [6] |

A.M. James, A.C. Smith, S. Ding, et al., Sci. Rep. 10 (2020) 20254. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-77261-1 |

| [7] |

P. Chen, J. Sun, C.J. Zhu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202203878. DOI:10.1002/anie.202203878 |

| [8] |

T. Yang, A. Cuesta, X. Wan, et al., Nat. Chem. Biol. 18 (2022) 934-941. DOI:10.1038/s41589-022-01019-1 |

| [9] |

S.B. Lee, J. Yu, H. Kim, et al., J. Med. Chem. 66 (2023) 2893-2903. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01926 |

| [10] |

A.M.M. Rangaswamy, M.H.R. Beh, E. Soleimani, et al., J. Org. Chem. 87 (2022) 13542-13555. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.2c01000 |

| [11] |

P. Chen, G. Tang, C. Zhu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 3844-3849. DOI:10.1021/jacs.2c11595 |

| [12] |

P.K. Pal, W.J. Wechter, R.F. Colman, J. Biol. Chem. 250 (1975) 8140-8147. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)40827-2 |

| [13] |

R.M. Scoggins, A.E. Summerfield, R.A. Stein, et al., Biochemistry 35 (1996) 9197-9203. DOI:10.1021/bi952909d |

| [14] |

M.P. Kamps, S.S. Taylor, B.M. Sefton, Nature 310 (1984) 589-592. DOI:10.1038/310589a0 |

| [15] |

S.S. Khandekar, B.B. Feng, T. Yi, et al., J. Biomol. Screen. 10 (2005) 447-455. DOI:10.1177/1087057105274846 |

| [16] |

S.J. Ratcliffe, T. Yi, S.S. Khandekar, J. Biomol. Screen. 12 (2007) 126-132. DOI:10.1177/1087057106296685 |

| [17] |

G. Renzone, A.M. Salzano, S. Arena, et al., J. Proteome. Res. 5 (2006) 2019-2024. DOI:10.1021/pr0601234 |

| [18] |

M.P. Patricelli, A.K. Szardenings, M. Liyanage, et al., Biochemistry 46 (2007) 350-358. DOI:10.1021/bi062142x |

| [19] |

M.P. Patricelli, T.K. Nomanbhoy, J. Wu, et al., Chem. Biol. 18 (2011) 699-710. DOI:10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.04.011 |

| [20] |

M. Saraste, P.R. Sibbald, A. Wittinghofer, Trends. Biochem. Sci. 15 (1990) 430-434. DOI:10.1016/0968-0004(90)90281-F |

| [21] |

S.K. Hanks, T. Hunter, FASEB J. 9 (1995) 576-596. DOI:10.1096/fasebj.9.8.7768349 |

| [22] |

U.P. Dahal, A.M. Gilbert, R.S. Obach, et al., MedChemComm 7 (2016) 864-872. DOI:10.1039/C6MD00017G |

| [23] |

G.R. Grimsley, J.M. Scholtz, C.N. Pace, Protein. Sci. 18 (2009) 247-251. DOI:10.1002/pro.19 |

| [24] |

Q. Zhao, X. Ouyang, X. Wan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 680-685. DOI:10.1021/jacs.6b08536 |

| [25] |

B. Ruprecht, J. Zecha, S. Heinzlmeir, et al., ACS Chem. Biol. 10 (2015) 2743-2752. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.5b00616 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35