Dysidavarones A–C (1–3, Fig. 1) are sesquiterpene quinone meroterpenoids isolated from Dysidea avara by Lin and coworkers in 2012 [1]. These three meroterpenoids possess an unprecedented bridged bicyclo[3.3.1]nonane ring system with three successive stereocenters within the molecules, two of which are quaternary carbon centers. Cytotoxicity evaluation showed that dysidavarone A (1) exhibited a growth inhibitory effect against HeLa cells with an IC50 value of 39.9 µmol/L [1]. In addition, dysidavarone A (1) showed inhibitory activity against protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B, a major negative regulator in insulin and leptin signaling pathways, and a positive regulator of tumorigenesis and progression of cancers) with IC50 values of 9.98 µmol/L [1]. Dysidavarone A (1) was also demonstrated to show potent inhibitory effects against Gram-positive bacteria, in particular against various Staphylococci (MIC50 = 0.2–9.9 mg/mL) [2].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Structures and biosynthetic hypothesis of (+)-dysidavarones A–C (1–3) and “E” (7). | |

With their interesting structures, impressive bioactivities, and sparse availability from natural resources, dysidavarones received much attention from synthetic chemists since their isolation. Five research groups have achieved the total synthesis of dysidavarones A (1), B (2), or C (3) in the past decade [2–6]. Four of these synthetic routes utilized a steric hindrance-sensitive reductive alkylation reaction of a protected WielandiMiescher ketone derivative in liquid ammonia [2–5], whereas one employed a bioinspired tail-to-head cyclization strategy [6]. Here, we report a concise and divergent enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-dysidavarones A–C (1–3).

Biosynthetically, it was assumed that dysidavarones A–C (1–3) might be generated from a common precursor, such as 4, as shown in Fig. 1. Specifically, the connection of the C6′ of the hydroquinone motif with C7 of the decalin moiety would give rise to tetracyclic diene 5, which possesses the bridged bicyclic[3.3.1]nonane ring system of dysidavarones A–C (1–3). Oxidation of the p-hydroquinone moiety of 5 would afford predysidavarone 6. It was suspected that the ethoxy group within dysidavarones A–C (1–3) might be introduced onto predysidavarone 6 as a precursor compound during extraction with solvent ethanol [1]. Thus, compound 7, a regioisomer of dysidavarone C (3), might also be a “natural product”, which was tentatively named as “dysidavarone E” (7). Introduction of the ethoxy group into predysidavarone 6 would give dysidavarones C (3) and “E” (7). Predysidavarone 6 could be transformed into quinone 8 under acidic conditions. Introduction of the ethoxy group into quinone 8 would yield dysidavarones A (1) and B (2), which also could be formed from dysidavarones “E” (7) and C (3) under acidic conditions, respectively.

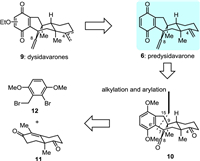

Guided by the above biosynthetic hypothesis, we carried out a retrosynthetic analysis of dysidavarones A–C (1–3). Since dysidavarones A–C (1–3) and “E” (7) could be prepared in a divergent way from predysidavarone 6, we focused the retrosynthetic analysis for all three natural products on this key intermediate. As depicted in Fig. 2, predysidavarone 6 could be easily transformed from tetracyclic diketone 10 through oxidation of the protected hydroquinone moiety and methylenation of the carbonyl groups at C4 and C8. Further disassembly of both C6′–C7 and C15–C9 single bonds of tetracyclic diketone 10 would give rise to Wieland...Miescher ketone derivative 11 and benzyl bromide 12.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Retrosynthesis of dysidavarones. | |

Our adventure for the total synthesis of dysidavarones A–C (1–3) started with the investigation of the coupling of Wieland...Miescher ketone derivative 11 and benzyl bromide 12. Wieland–Miescher ketone and its derivatives (e.g., 11) are versatile building blocks as starting materials and have been employed in the total synthesis of numerous natural products [7–9]. Usually, the more reactive C4 carbonyl group of 11 is protected before further selective transformations (e.g., alkylation), and the protecting group is then removed at a later stage [7–9]. To save synthetic steps and reduce overall effort, we envisioned that the protecting group might not be essential for the alkylation reaction.

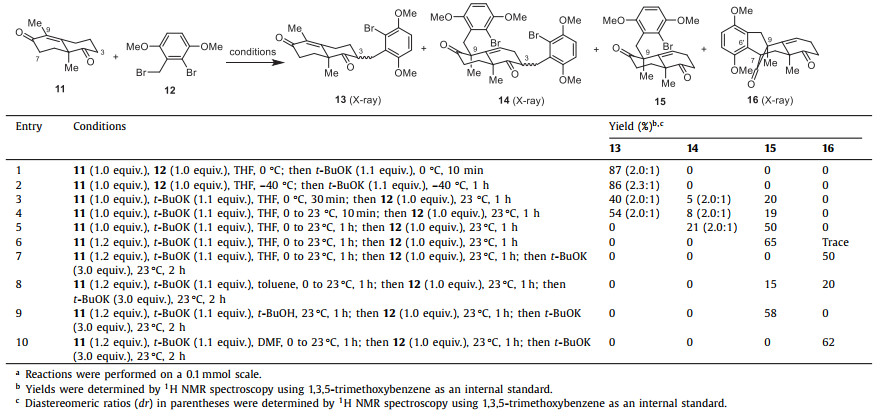

With this assumption in mind, we investigated the direct alkylation of the unprotected Wieland–Miescher ketone derivative 11 with benzyl bromide 12, as summarized in Table 1. Initially, adding t-BuOK to a mixture of 11 and 12 in THF at 0 ℃ led to undesired C3 alkylation products 13 in high combined yield and moderate diastereoselectivity (87%, 2.0:1 dr, entry 1). The alkylation position of 13 was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis of one of the diastereoisomers (13A, Scheme 1). Lowering the reaction temperature afforded almost the same yield and slightly higher diastereoselectivity (86%, 2.3:1 dr, entry 2). Satisfactorily, exposure of a pre-mixed solution of 11 and t-BuOK (30 min at 0 ℃) to 12 gave aforementioned C3 alkylation products 13 and double alkylation products 14 along with 20% of desired C9 alkylation product 15 (entry 3). The structure of double alkylation products 14 was also verified by X-ray crystallographic analysis of one of the diastereoisomers (14A, Scheme 1). Higher temperature and shorter reaction time (23 ℃ and 10 min, entry 4) gave similar results (entry 3). A sufficiently long reaction time at a higher temperature (1 h at 23 ℃) gave the desired C9 alkylation product 15 as a major product (50%) and a small portion of double alkylation products 14 (21%, entry 5). Increasing 11 from 1.0 equiv. to 1.2 equiv. suppressed the formation of double alkylation products 14, giving 15 in 65% yield as the sole product (entry 6), which is consistent with Newhouse's observations, but in higher yield and diastereoselectivity [10].

|

|

Table 1 Investigation of the coupling of Wieland–Miescher ketone derivative 11 and benzyl bromide 12a. |

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Proposed mechanism for the coupling of Wieland–Miescher ketone derivative 11 and benzyl bromide 12. | |

In studying the coupling of Wieland–Miescher ketone derivative 11 with benzyl bromide 12, a very small amount of tetracyclic diketone 16 was isolated from the reaction mixture in some cases, such as in entry 6. Tetracyclic diketone 16 possesses the core carbon backbone of dysidavarones A–C (1–3) and we thought that 16 was derived from 15 by intramolecular arylation. We assumed that an excess of t-BuOK could facilitate the conversion of 15 to 16. Indeed, when 3 additional equivalents of t-BuOK were added to the reaction mixture, 16 were isolated in 50% yield (entry 7). We also suspected that the solvent might affect the transformation of 15 to 16. Thus, a series of solvents were examined and we found that toluene and t-BuOH resulted in poor conversion of 15 (entries 8 and 9), whereas DMF gave superior yield, affording 16 in 62% yield (entry 10).

To explain the selectivity of different alkylation products under different reaction conditions, we would like to propose a mechanism, as illustrated in Scheme 1. At lower temperatures (≤0 ℃), the enolate corresponding to the C3 carbanion 17 is formed under kinetic control [11] and can be directly quenched by the addition of benzyl bromide 12 as an alkylating reagent to afford 13 as a mixture of diastereoisomers (87%, 2.0:1 dr). At higher temperatures and a sufficiently long reaction time (such as 23 ℃ for 1 h), the C3 carbanion 17 converts to the thermodynamically more stable dienolate via intermolecular proton exchange. This species can be either represented as the C1 carbanion 18 or the C9 carbanion 19, respectively, and reacts with benzyl bromide 12 in α-position to give 15 as a major product. To support this hypothesis, a series of control experiments were performed. C3 alkylation products 13 (a 2.0:1 mixture of diastereoisomers) were treated with t-BuOK at 23 ℃ for 1 h before benzyl bromide 12 was added. As we expected, double alkylated products 14 were obtained (61% yield, 2.0:1 dr) via the formation of the thermodynamically favored enolate corresponding to carbanion 20. Additionally, treatment of a mixture of diketone 15 and benzyl bromide 12 with t-BuOK at 0 ℃ resulted in the aforementioned double alkylated products 14 in 84% yield and 2.0:1 dr via intermediate 21, whereas treatment of 15 with t-BuOK at 23 ℃ in the absence of benzyl bromide 12 afforded the tetracyclic diketone 16 in 88% yield, presumably via direct intramolecular arylation of enolate 22 [12].

Having successfully established efficient reaction conditions for the preparation of tetracyclic diketone 16, we moved to the synthesis of (+)-dysidavarones A–C (1–3) according to the retrosynthesis. As shown in Scheme 2, tetracyclic diketone 16 was efficiently synthesized from the Wieland...Miescher ketone derivative 11 and benzyl bromide 12 in a one-pot procedure under previously established conditions (entry 10, Table 1) in 60% yield on a gram scale. However, the direct reduction of the Δ(1,10) double bond of diketone 16 with the correct configuration at C10 proved to be a challenging task. Various protocols for heterogeneous and homogeneous hydrogenation or metal-catalyzed hydrogen atom transfer reactions [13–17] exclusively yielded the undesired diastereomer 23.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Divergent synthesis of 10-epi-dysidavarones A–C (29, 30, and 27). | |

In order to increase the diversity of the structural space of dysidavarone analogs to be biologically studied, we decided to proceed with this compound for now. As shown in Scheme 2, double methylenation of diketone 23 using Wittig reagent (Ph3P═CH2) gave the tetracyclic diene 24 in 94% yield, the structure of which was confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis (see Supporting information for details). Direct oxidation of 24 with cerium ammonium nitrate (CAN) or other oxidating reagents resulted in either decomposition of starting material or poor isolated yield of the desired product. Delightfully, the removal of one of the O-methyl groups with n-BuSLi [18] and subsequent oxidation with O2 and salcomine gave the desired quinone 25 in 70% overall yield over both steps. Introduction of an ethoxy group to quinone 25 with Et3N in EtOH under an oxygen atmosphere resulted in 10-epi-dysidavarones “E” (26) and C (27) in 41% combined yield (26:27 = 3:1) [19]. Quinone 25 was converted to 28 under acidic conditions in 76% yield and the introduction of an ethoxy group afforded 10-epi-dysidavarones A (29) and B (30) in 35% combined yield (29:30 = 5:1). Alternatively, 10-epi-dysidavarones A (29) and B (30) also could be obtained from 10-epi-dysidavarones “E” (26) and C (27) in 70% and 50% yield, respectively, under acidic conditions.

To complete the total synthesis of (+)-dysidavarones A–C (1–3), we envisioned that the diastereoselectivity of the hydrogenation of 16 could be reversed by exploiting intramolecular hydroxy-directed hydrogenation. For this reason, the C4 ketone functionality of tetracyclic diketone 16 was first reduced by l-selectride to give alcohol 31 in high yield and diastereoselectivity (95%, > 15:1 dr) (Scheme 3). The orientation of the hydroxy group of 31 was verified by X-ray crystallographic analysis (see Supporting information for details). As expected, the hydroxyl-directed hydrogenation of 31 using Crabtree's catalyst [20] now exclusively afforded alcohol 32 with the correct configuration in 95% yield. Dess–Martin periodinane (DMP) oxidation of alcohol 32 rendered diketone 10 with very high efficiency (94%). Methylenation of diketone 10 and direct oxidation with CAN gave predysidavarone 6 in 80% overall yield over the two steps. Thus, the stage was set for the completion of the divergent total synthesis of (+)-dysidavarones A–C (1–3) and “E” (7). Introduction of the ethoxy group onto predysidavarone 6 with Et3N in EtOH under an oxygen atmosphere led to (+)-dysidavarones “E” (7) and C (3) in acceptable combined yield (55%, 7:3 = 1.1:1) [19]. When predysidavarone 6 was converted to the isomeric quinone 8 under acidic conditions in 91% yield, the subsequent introduction of the ethoxy group gave (+)-dysidavarones A (1) and B (2) in moderate combined yield (50%, 1:2 = 1:1). As in the epimeric series, (+)-dysidavarones A (1) and B (2) could also be prepared from (+)-dysidavarones “E” (7) and C (3) in 92% yield, respectively. The spectroscopic data and optical rotation of synthetic (+)-dysidavarones A–C (1–3) matched well with those reported for the natural products [1].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. Divergent synthesis of dysidavarones A–C (1–3) and “E” (7). | |

In summary, we have achieved a concise and divergent enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-dysidavarones A–C (1–3) and “E” (7) via the common intermediate predysidavarone (6). The highly strained and bridged eight-membered skeleton of predysidavarone 6 was constructed by a one-pot intermolecular alkylation and intramolecular arylation of Wieland–Miescher ketone derivative 11 and benzyl bromide 12. The total synthesis of (+)-dysidavarones A–C (1–3) was concluded by a late introduction of the ethoxy group into the quinone moiety of the precursor predysidavarone under mild conditions. This reveals a possible biogenetic origin of the ethoxy group in these natural products and provides an avenue for the diversity-oriented synthesis of dysidavarone analogs for further evaluation of their anti-cancer activity. Furthermore, the detailed investigation of the selective alkylation of Wieland–Miescher ketone derivative 11 with benzyl bromide 12 contributes to a better understanding of these versatile building blocks, opening new valuable options for the synthetic use of Wieland–Miescher ketone and its derivatives and will certainly find future application in the synthesis of natural products and pharmaceutically useful compounds.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22171146, 21971121, and 22188101 to ZL) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2021M701775 to CC). We thank Profs Yanxing Jia (Peking University), Yefeng Tang (Tsinghua University), Zhiqiang Ma (South China University of Technology), Bo Su (Nankai University), and Quan Zhang (Nankai University) for their helpful discussion. We are grateful to Dr. Ruocheng (Ronnie) Yu (Rice University) and Prof. Hans-Günther Schmalz (University of Cologne) for their kind help during the preparation of this manuscript. We thank Dr. Qingxin Cui (Nankai University) for NMR spectroscopic assistance and Dr. Quanwen Li (Nankai University) for X-ray crystallographic analysis.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108338.

| [1] |

W.H. Jiao, X.J. Huang, J.S. Yang, et al., Org. Lett. 14 (2012) 202-205. DOI:10.1021/ol202994c |

| [2] |

B. Schmalzbauer, J. Herrmann, R. Müller, D. Menche, Org. Lett. 15 (2013) 964-967. DOI:10.1021/ol400156u |

| [3] |

Y. Fukui, K. Narita, T. Katoh, Chem. Eur. J. 20 (2014) 2436-2439. DOI:10.1002/chem.201304809 |

| [4] |

C. Yu, X. Zhang, J. Zhang, Z. Shen, Tetrahedron 72 (2016) 4337-4345. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2016.05.073 |

| [5] |

Y.M. Li, Y.T. Sun, B.Y. Li, H.B. Qin, Org. Lett. 23 (2021) 7254-7258. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02641 |

| [6] |

W. Zhu, Q. Yin, Z. Lou, M. Yang, Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 6633. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-34404-4 |

| [7] |

B. Bradshaw, J. Bonjoch, Synlett 23 (2012) 337-356. DOI:10.1055/s-0031-1290107 |

| [8] |

Z.Q. Liu, Curr. Org. Synth. 16 (2019) 328-341. DOI:10.2174/1570179416666190328233710 |

| [9] |

H. Hagiwara, Prod. Commun. 15 (2020) 1-17. |

| [10] |

D.E. Kim, J.E. Zweig, T.R. Newhouse, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 1479-1483. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b13127 |

| [11] |

P.A. Grieco, S. Ferriño, T. Oguri, J. Org. Chem. 44 (1979) 2593-2594. DOI:10.1021/jo01328a063 |

| [12] |

C. Adouama, M.E. Budén, W.D. Guerra, et al., Org. Lett. 21 (2019) 320-324. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03831 |

| [13] |

J.C. Lo, J. Gui, Y. Yabe, C.M. Pan, P.S. Baran, Nature 516 (2014) 343-348. DOI:10.1038/nature14006 |

| [14] |

K. Iwasaki, K.K. Wan, A. Oppedisano, S.W.M. Crossley, R.A. Shenvi, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 1300-1303. DOI:10.1021/ja412342g |

| [15] |

J.C. Lo, Y. Yabe, P.S. Baran, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 1304-1307. DOI:10.1021/ja4117632 |

| [16] |

S.A. Green, S.W.M. Crossley, J.L.M. Matos, et al., Acc. Chem. Res. 51 (2018) 2628-2640. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00337 |

| [17] |

J. Wu, Z. Ma, Org. Chem. Front. 8 (2021) 7050-7076. DOI:10.1039/D1QO01139A |

| [18] |

P.A. Bartlett, W.S. Johnson, Tetrahedron Lett. 46 (1970) 4459-4462. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)83950-2 |

| [19] |

C. Chong, Q. Zhang, J. Ke, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 13807-13813. DOI:10.1002/anie.202100541 |

| [20] |

R.H. Crabtree, H. Felkin, T. Fillebeen-Khan, G.E. Morris, J. Organomet. Chem. 168 (1979) 183-195. DOI:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)83274-X |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35