Ethene is a valuable platform chemical in modern chemical industry. The traditional route for ethene production is steam cracking of the naphtha from crude oil [1]. Alternatively, high-temperature cracking of ethane is another ethene production approach, because of the exploitation of shale gas that supplies abundant ethane over the past decade [2–4]. Although being used industrially, operating these two recipes requires harsh conditions, including high reaction temperature (> 900 ℃), coupled with fast outlet gas cooling (< 800 ℃) and short contact time (~0.3 s) to avoid overoxidation of ethene [5–7]. Apart from steam cracking, thermocatalytic oxidative and non-oxidative ethane dehydroge-nation (EDH) to produce ethene have stimulated great interest in recent years [8–10]. The oxidative EDH involving an oxidant (e.g., O2) is thermodynamically favorable owing to the exothermic feature but suffers easily from overoxidation to form CO2 [11,12]. Comparatively, the nonoxidative EDH bears an obvious merit in preventing overoxidation, yet this route usually encounters severe catalyst deactivation caused by coke formation and metal sintering at high temperatures [13], which imposes complex and even high-cost processes to regenerate the catalysts [14].

Besides thermal strategies, the technology of light-driven photocatalysis has recently exhibited immense vitality in dehydrogenation of alkanes to olefins [15–24], which enables the break of thermodynamic limitation and the handling of the reactions under mild conditions. For example, Pt+-loaded black TiO2 presents excellent conversion and high stability for cyclohexane dehydrogenation, but a much slower conversion rate for EDH, even at a very negative partial pressure [19]. Another photocatalytic EDH is achieved over Cu/TiO2 under UV light irradiation, affording moderate conversion (1.7%) and high ethene selectivity (98.41%) using diluted ethane (10%) [20]. Despite these achievements, the study of photocatalytic EDH is just in its infancy, and it is challenging to realize efficient and selective light-initiated EDH for making ethene, especially those mediated by non-noble-metal catalysts in undiluted ethane.

Herein, we demonstrate the facile preparation of an Ov-rich LaVO4-Ov photocatalyst, which displays high activity and stability for EDH via dynamic collaborations between Olatt. and Ov. The LaVO4-Ov material is created through a one-pot hydrothermal method and characterized by diverse physiochemical techniques. Under simulated sunlight irradiation, pristine LaVO4-Ov actively dehydrogenates pure C2H6 to form C2H4 (15.4 µmol h−1 g−1) and CO (26.8 µmol h−1 g−1) with a conversion of 2.3%. By depositing a small amount of Pt as a cocatalyst, the yield and selectivity of C2H4 are promoted to 275 µmol h−1 g−1 and 96.8%. Noteworthily, the photocatalyst appears nearly no coke formation after the reaction. The 13C and 18O labeled isotope reactions validate that C2H4 produces from C2H6, while CO originates from C2H6 and Olatt.. Importantly, the consumed Olatt. can recover readily by contacting the catalyst with O2 in air, which thus constructs a dynamic cycle of Olatt. and achieves a simplistic catalyst regeneration. The restored LaVO4-Ov displays good reusability and affords a turnover number of about 305 based on the determined catalytic-active sites. The Ov is revealed to strengthen optical harvesting, boost ethane capture/activation, and facilitate separation and migration of charge carriers, contributing to the augmentation of photocatalytic efficiency. DFT and in-situ DRIFTS identify the key intermediates in the EDH process and support the construction of the possible reaction mechanism.

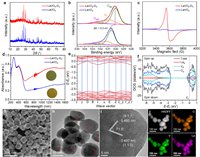

The LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 samples exhibit similar X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns with all diffraction peaks indexed to a monoclinic LaVO4 phase (Fig. 1a) [25]. The Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR) indicate that Ov formation affects the chemical feature of the VO43− unit (Fig. S1 in Supporting information) [26,27]. The XPS survey spectra show only La, V and O elements, except C, indicating their high purities, and further analysis on La and V elements reveals the forms of La3+ and V4+/V5+ cations (Fig. S2 in Supporting information) [27,28]. The asymmetric O 1s spectrum comprises three peaks with the dominant one at 529.7 eV (Fig. 1b), attributing to Olatt.. The additional two peaks at 530.5 and 532.0 eV correspond to Ov and surface adsorbed oxygen species (Oads.), respectively [29–31]. Compared with LaVO4-Ov, the V 2p and O 1s spectra of LaVO4 are negatively shifted by about 0.2 eV, meaning that introducing Ov into LaVO4 endows these elements with enriched electrons [32].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (a) XRD patterns, (b) O 1s spectra, (c) EPR spectra, (d) DRS and colors of LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4. (e) The calculated band structure, (f) DOS, (g) FESEM image, (h) TEM image, (i) HRTEM image, and (j) EDS maps of LaVO4-Ov. | |

The defective structure of LaVO4-Ov was probed by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). A strong signal (g = 1.977) is detected for LaVO4-Ov, but not for LaVO4 (Fig. 1c), which confirms the existence of Ov-related V4+ species [28]. Mesopores are revealed present in LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 (Fig. S3 in Supporting information), and the former holds a larger specific surface area than the latter, which underlines that formation of Ov endows LaVO4 with beneficial texture properties for heterogeneous photocatalysis.

The UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) indicate LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 have broad light absorption in UV-visible region (Fig. 1d). Besides, LaVO4-Ov exhibits a reinforced infrared harvesting, compared with LaVO4, due to the presence of Ov that elevates the Fermi level and builds defect level in the bandgap [29,33–36]. The Tauc plots determine the bandgap energies (Eg) of LaVO4-Ov (2.21 eV) and LaVO4 (2.28 eV) (Fig. S4 in Supporting information). From the Mott-Schottky curves with positive slopes (Fig. S5 in Supporting information), the flat band potentials of LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 are estimated at 0.46 and 0.50 V (vs. NHE), which are considered as their conduction band (CB) potentials. Therefore, the band structures of LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 are defined (Fig. S6 in Supporting information).

The band structures and density of states (DOS) of LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 were theoretically simulated. The modeled LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 feature indirect bandgap with Eg values of about 2.4 and 2.5 eV (Fig. 1e and Fig. S7a in Supporting information), respectively, close to the experimental data. The DOS indicate that the Fermi levels of LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 are located above the valence band (VB) maximum (Fig. 1f and Fig. S7b in Supporting information), due to perfect or lower energy electron filling. Moreover, the VBs are dominated by oxygen p-orbital, inferring that the photo-formed holes will retention on oxygen atoms for oxidation reactions, while the CBs consist of the d-orbitals of V and La with a localized electronic density of states. These results suggest that Ov not only shifts the Fermi level of LaVO4, but also makes it overlap with the CB. Moreover, the small difference in the Eg values of LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 reflects that the intensified photoabsorption of LaVO4-Ov should be induced by oxygen defects on the surface, rather than in the bulk.

The field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) image of LaVO4-Ov presents a morphology of nanoparticles in size around 100 nm (Fig. 1g). The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image exposes the presence of mesopores (indicated by arrows, Fig. 1h), which might be the result of ammonia gas release during the crystallization process. In the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image (Fig. 1i), two lattice spacing values of 0.485 and 0.497 nm, with an inclination angle of 71.5°, are well resolved, correspond to the (011) and (110) facets of monoclinic LaVO4. Further analysis of the HRTEM image reveals that the particle has high crystallinity and dominantly exposes (110) facets on the surface [37]. Energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS) maps display the uniform distribution of La, V and O elements of the LaVO4-Ov material (Fig. 1j).

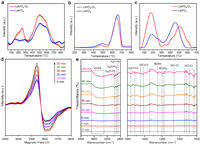

Photocatalytic EDH activities of the samples were evaluated by simulated sunlight in pure ethane with a partial pressure of 1 atm, which are much harsh conditions compared with previous works using diluted ethane at negative pressures [19,20,38]. The LaVO4 catalyst is active to the EDH reaction with C2H4 and CO as the main products (Fig. 2a). In comparison, LaVO4-Ov presents a enhanced activity, affording C2H4 and CO at rates of 15.4 and 26.8 µmol h−1 g−1, respectively, which corresponds to a C2H4 selectivity of 47.8% and a C2H6 conversion of 2.3%. The moderate C2H4 selectivity may result from the strong oxidizing ability of the photoinduced holes that leads to C2H4 overoxidation to form CO. However, the EDH efficiency is expected to be controllable by tailoring the active sites and redox potentials of LaVO4-Ov. Positively, the preliminary results reveal that the yield rate and selectivity of C2H4 are improved to 275 µmol h−1 g−1 and 96.8% by depositing Pt as a cocatalyst (Fig. 2b), and detailed studies are ongoing in our group. The high performance of LaVO4-Ov is mainly attributed to the presence of Ov, serving as active sites for the EDH reaction. Also, Ov enhances light-to-heat conversion to drive the reaction. Specifically, LaVO4-Ov with a strong infrared absorption delivers a higher photo-to-thermal conversion than LaVO4 (Fig. S8 in Supporting information), that is, 170 ℃ for LaVO4-Ov and 130 ℃ for LaVO4.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) Photocatalytic ODE performance of different samples, (b) activities of LaVO4-Ov and Pt/LaVO4-Ov samples, (c) activity cycling tests of LaVO4-Ov after regeneration. MS spectra of (d) C2H4 and (e) CO produced from the 13CH312CH3 isotope experiment, and (f) CO produced from 12CH312CH3 over the used LaVO4-Ov after regenerating with 18O2. | |

Interestingly, CO produces from EDH without an oxidant, indicating CO should come from C2H6 oxidation by Olatt. of the catalysts. The participation of Olatt. is mirrored by the time-dependent activity of LaVO4-OV, showing a gradual decay in the 4 h reaction (the first cycle, Fig. 2c), due to consumption of catalytic-active Olatt and formation excessive Ov. To assess the reusability, the used LaVO4-Ov is employed to catalyze two sets of 4h-reaction, but appears substantial deactivation (Fig. S9 in Supporting information). In another test, when the used LaVO4-Ov is first exposed to air for regeneration and then re-applied to run the reaction repeatedly, it well preserves the original activity (Fig. 2c). These highlight that Olatt. realizes regeneration by exposure to air, attaining a dynamic cycle of Olatt. and the recovery of its intrinsic activity [21,39,40], together with its color becomes almost the same to the fresh sample (Fig. S10 in Supporting information). In other words, LaVO4-Ov holds an oxygen storage/release ability, like the well-studied CeO2 [41,42]. Therefore, CeO2 is also utilized for photocatalytic EDH, but just exhibits negligible activity (Fig. 2a), which however stresses the superior performance of LaVO4-Ov.

Control experiments indicate no product yields without LaVO4-Ov, C2H6, or photoirradiation (Fig. S11 in Supporting information), suggesting that excitation of the photocatalyst triggers the EDH reaction. To estimate the contribution of thermal-catalysis, EDH is conducted at 200 ℃ (higher than 170 ℃ in photocatalysis) in dark, just affording a small C2H4/CO production (Fig. S11), emphasizing the high EDH efficiency stems primarily from photocatalysis.

XRD, XPS and TEM reveal no crystal, surface, and structural changes for LaVO4-Ov after activity cycling tests (Fig. S12 in Supporting information), highlighting the outstanding stability of the photocatalyst after regeneration. Moreover, thermogravimetry (TG) and TG-mass spectroscopy (TG-MS) tests disclose nearly no noticeable carbon deposition forms on spent LaVO4-Ov (Fig. S13 in Supporting information), which underlines the superiority of photocatalysis in preventing coke formation.

13C and 18O labeled isotope experiments were conducted to track the origin of C2H4 and CO. First, the fresh LaVO4-Ov is employed for dehydrogenating 13CH312CH3. The MS spectrum of C2H4 gives dominated fragments of 13CH212CH2 (m/z = 29) (Fig. 2d and Fig. S14 in Supporting information), while those of CO are indexed to 13CO (m/z = 29) and 12CO (m/z = 28) (Fig. 2e). Such results confirm that C2H4 derives from C2H6, while CO comes from C2H6 and Olatt.. In the 18O-labeled experiment, the used LaVO4-Ov is exposed to 18O2 for regeneration, and then applied to catalyze 12CH312CH3 conversion, which results in the detections of main C18O (m/z = 30) and C16O (m/z = 28) (Fig. 2f), proving Olatt. recovery of the catalyst from molecular O2 [43]. Such isotope experiments solidly validate the sources of C2H4 and CO and directly illustrate the dynamic Olatt. loop of LaVO4-Ov.

The steady-state photoluminescence (PL) and time-resolved PL (TR-PL) spectra reveal that LaVO4-Ov manifests inhibited recombination and promoted separation of light-induced carriers, compared with LaVO4 (Fig. S15 in Supporting information). Meanwhile, the electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) indicate LaVO4-Ov retains a lowered charge-transfer resistance than LaVO4 (Fig. S16a in Supporting information), and the transient photocurrent responses reflect electron transfer in LaVO4-Ov is much faster than that in LaVO4 (Fig. S16b in Supporting information). These findings suggest Ov formation promotes separation and migration of the charges, thus boosting photocatalytic EDH efficiency.

Temperature-programmed desorption of ethane (C2H6-TPD) was carried out to probe the active sites of LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4. The C2H6-TPD profiles exhibit two broad signals centered at around 250 and 500 ℃ (Fig. 3a), attributing to physical and chemical adsorption of ethane, respectively. The corresponding peak areas of LaVO4-Ov are greater than that of LaVO4, indicating Ov of LaVO4-Ov promotes ethane adsorption. The determined number of active sites on LaVO4-Ov is about 2.68 µmol/g, and hence, the turnover number of the catalyst in the activity cycling tests reaches 305, confirming the catalytic nature of the photo-driven EDH reaction.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) C2H6-TPD, (b) H2-TPR and (c) O2-TPD profiles of LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4. (d) In situ EPR spectra of LaVO4-Ov in C2H6 under varied conditions. (e) In situ DRIFTS spectra of LaVO4-Ov in C2H6 under light irradiation for different durations. | |

The redox abilities of the catalysts were estimated by temperature-programmed reduction of hydrogen (H2-TPR) and O2-TPD. The H2-TPR profiles of LaVO4-Ov and LaVO4 display two peaks at around 485 and 650 ℃ (Fig. 3b), relating respectively to reduction of surface adsorbed oxygen and Olatt. [44]. Besides, the reduction peaks of LaVO4-Ov appear at the lower temperatures, indicative of its enhanced oxidation ability. Three desorption peaks are observed in the O2-TPD profile of LaVO4-Ov (Fig. 3c). The strongest desorption below 300 ℃ links to surface adsorbed oxygen species (Oads.) [44]. The small peak at around 330 ℃ is ascribed to the desorption of surface lattice oxygen (Os-latt.), which is reactive and affects catalytic properties [45]. The desorption above 350 ℃ represents the release of bulk lattice oxygen (Ob-latt.) [44,46], reflecting the structural stability. Compared to LaVO4-Ov, LaVO4 exhibits a markedly diminished desorption of Osorb., owing to its absence of Ov that reduces surface O2 adsorption. Furthermore, no clear desorption of Os-latt. evolves for LaVO4 because the lack of Ov makes its Os-latt. more stable. In addition, the desorption of Ob-latt. of LaVO4 presents at a lower temperature, revealing the higher structural stability of LaVO4-Ov. These results confirm LaVO4-Ov possess high redox ability, rich active sites, and enhanced oxygen storage capability.

To probe the reactive oxygen species and structural changes of the LaVO4-Ov photocatalyst, in situ EPR measurements were conducted. The EPR signal assigned to Ov-related V4+ species intensifies regularly according to the prolongation of irradiation time (Fig. 3d), which signifies the enrichment of Ov, due to the release of Olatt. for running the EDH reaction.

In-situ DRIFTS was employed to identify intermediates and elucidate processes of EDH. After adsorbing C2H6 in dark, LaVO4-Ov exhibits five distinct peaks assigned to stretching vibrations of C—H bonds (Fig. S17 in Supporting information) [17,20], suggesting efficient C2H6 adsorption by the catalyst. Upon light irradiation, signals of several new species are detected with the intensities heightened by prolonging the photoirradiation (Fig. 3e). The gradually enhanced band at 3680–3058 cm−1 reflects the accumulation of H2O (Table S1 in Supporting information) [47,48]. The vibrations of C—H (2975 and 2875 cm−1) and CH2 (2930 cm−1) bonds imply the generation of the key intermediates of CH3—CH2· and ·CH2—CH2· [17,20,49], which may be generated from dissociation adsorption of C2H6 on Ov. The involvements of these key species are also supported by detected vibrations corresponding to CH3 (1400 and 1380 cm−1) and C-C (1265, 1138, 1118, 1089 and 1031 cm−1) moieties. Notably, observation of featured vibrations of C=O (1763 and 1716 cm−1) and C=C (1650, 1619 and 1545 cm−1) bonds reveals the formation of CO and C2H4 [50–52]. In addition, the vibration at 1452 cm−1 points to the evolution of OH species during the reaction [17,48].

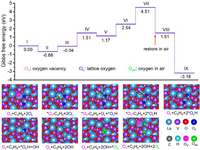

Based on the results of photocatalytic EDH, we further performed DFT calculations to explore the thermodynamic favorability of C2H6 transformation and Olatt. consumption. The reaction mechanism of alkane dehydrogenation co-steered by Ov and Olatt. has not been thoroughly tracked and deciphered on LaVO4-Ov. This mysterious mechanism is expected to be decoded on the recyclable LaVO4 benchmark platform. The LaVO4-Ov catalyst allows Ov to capture C2H6 with a low adsorption energy of −0.66 eV (Fig. 4, from Ⅰ to Ⅱ). The adjoining lattice oxygens are responsible for subsequent bonding with H to generate OH (Fig. 4, from Ⅲ to Ⅳ). The upward trend in free energy until complete desorption of 2OH (Fig. 4, from Ⅴ to Ⅶ), discloses that ethane dehydrogenation to ethene is a challenging process that requires photothermal energy to drive. After that, it is very favorable for the adsorption of O2 because of a downward trend in energy (Fig. 4, Ⅷ), which can perfectly refill the consumed Olatt. sites after decomposing into two oxygen atoms (Fig. 4, Ⅸ). Such theoretical results are in good agreement with the hao de activity cycling tests. In contrast, LaVO4 without Ov is inferior in both ethane adsorption and OH desorption (Fig. S18 in Supporting information), demonstrating the effectiveness of more stable intrinsic Ov in EDH, rather than metastable Ov generated by depleting Olatt..

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Calculated potential energy diagram and the corresponding optimized geometries of active species over LaVO4-Ov by DFT. | |

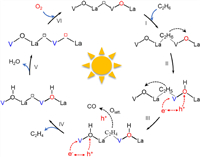

The photocatalytic EDH process is proposed based on the experimental and theoretical results (Fig. 5). Initially, C2H6 is preferentially adsorbed on Ov of LaVO4-Ov (step Ⅰ). Upon light irradiation, the photoinduced holes are trapped by surface Olatt. to produce active O•− species [21], which enables H abstraction from adsorbed C2H6, yielding the C2H5/C2H4 fractions and adsorbed OH groups (steps Ⅱ and Ⅲ). Concurrently, the electrons reduce V5+ to form V4+, which is supported by XPS analyses on used LaVO4-Ov catalyst (Fig. S19a in Supporting information). Afterward, the C2H4 species release from catalyst surface to generate ethene gas (step Ⅳ), while the adsorbed OH groups desorb in form of H2O (step Ⅴ), rendering the catalyst with decreased Olatt. and increased Ov (Fig. S19b in Supporting information). Due to the strong oxidative ability of photogenerated holes, overoxidation of C2H4 also occurs in cooperation of Olatt., resulting in CO release. Lastly, being exposed to O2, V4+ cation reduces O2 to Olatt. positioned in the lattice with itself oxidized to V5+ (step Ⅵ), achieving a dynamic cycle of Olatt. and catalyst regeneration, which finishes the catalytic loop.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. The proposed photocatalytic EDH mechanism over LaVO4-Ov (the black box represents the Ov of fresh LaVO4-Ov, and the red box represents the Ov created from the consumption of Olatt. during the reaction). | |

In summary, demonstrated herein is the facile synthesis of a LaVO4-Ov catalyst with Ov and its function in light-driven EDH under mild conditions. The photocatalytic EDH reaction follows a mechanism mediated dynamically by Olatt. and Ov. Bare LaVO4-Ov grants effective dehydrogenation of undiluted C2H6 to produce C2H4, together with CO, while Pt-loaded LaVO4-Ov affords greatly enhanced C2H4 production and selectivity. Remarkably, LaVO4-Ov shows an excellent coking-resistant property and achieves fine reusability via a simplistic regeneration with air exposure to restore the depleted Olatt.; while its Ov promotes optical absorption, ethane adsorption/activation, and charge separation/transport to boost the photocatalytic efficiency. This work may advance the feasibility of photocatalysis technology for EDH with renewable solar resource. Also, the recoverable catalytic-active Olatt. of LaVO4-Ov is anticipated to extend for driving some oxidant-sensitive organic transformations in a heterogeneous fashion.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work is financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Nos. 2021YFA1502100 and 2022YFE0114800) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21973014).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108313.

| [1] |

T. Amrillah, A.R. Supandi, V. Puspasari, A. Hermawan, Z.W. Seh, Trans. Tianjin Univ. 28 (2022) 307-322. DOI:10.1007/s12209-022-00328-9 |

| [2] |

J.M. Venegas, W.P. McDermott, I. Hermans, Acc. Chem. Res. 51 (2018) 2556-2564. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00330 |

| [3] |

R. Yao, J.E. Herrera, L. Chen, Y.H.C. Chin, ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 6952-6968. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c01073 |

| [4] |

Y. Zhou, F. Wei, J. Lin, et al., ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 7619-7629. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c02347 |

| [5] |

Z. Maeno, S. Yasumura, X. Wu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 4820-4832. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b13865 |

| [6] |

J. Liu, N. He, Z. Zhang, et al., ACS Catal. 11 (2021) 2819-2830. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.1c00126 |

| [7] |

M. Numan, E. Eom, A. Li, et al., ACS Catal. 11 (2021) 9221-9232. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.1c01156 |

| [8] |

J.J.H.B. Sattler, J. Ruiz-Martinez, E. Santillan-Jimenez, B.M. Weckhuysen, Chem. Rev. 114 (2014) 10613-10653. DOI:10.1021/cr5002436 |

| [9] |

Y. Bian, M. Kim, T. Li, A. Asthagiri, J.F. Weaver, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 2665-2672. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b13599 |

| [10] |

S. Najari, S. Saeidi, P. Concepcion, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 50 (2021) 4564-4605. DOI:10.1039/d0cs01518k |

| [11] |

Y. Pan, A. Bhowmick, W. Wu, et al., ACS Catal. 11 (2021) 9970-9985. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.1c02676 |

| [12] |

R. Jin, M. Peng, A. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 18921-18925. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b06986 |

| [13] |

M.D. Porosoff, M.N.Z. Myint, S. Kattel, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 15501-15505. DOI:10.1002/anie.201508128 |

| [14] |

Z. Yang, H. Li, H. Zhou, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 16429-16436. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c07792 |

| [15] |

C. Zhao, M. Xi, J. Huo, C. He, L. Fu, Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107213. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.02.018 |

| [16] |

Q. Li, H. Yue, C. Liu, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 395 (2020) 125120. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125120 |

| [17] |

R. Zhang, H. Wang, S. Tang, et al., ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 9280-9286. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b02441 |

| [18] |

Q.H. Zheng, C. Chen, S.M. Cao, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107273. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.02.078 |

| [19] |

L. Zhang, L. Liu, Z. Pan, et al., Nat. Energy 7 (2022) 1042-1051. DOI:10.1038/s41560-022-01127-1 |

| [20] |

L. Song, R. Zhang, C. Zhou, et al., Chem. Commun. 59 (2023) 478-481. DOI:10.1039/d2cc05438h |

| [21] |

S. Song, H. Song, L. Li, et al., Nat. Catal. 4 (2021) 1032-1042. DOI:10.1038/s41929-021-00708-9 |

| [22] |

S. Shoji, X. Peng, A. Yamaguchi, et al., Nat. Catal. 3 (2020) 148-153. DOI:10.1038/s41929-019-0419-z |

| [23] |

D. Gao, W. Li, H. Wang, G. Wang, R. Cai, Trans. Tianjin Univ. 28 (2022) 245-264. DOI:10.1007/s12209-022-00326-x |

| [24] |

L. Chen, Q. Liu, J. Yang, Y. Li, G. Li, Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107335. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.058 |

| [25] |

Y. Xu, J. Liu, M. Xie, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 357 (2019) 487-497. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2018.09.098 |

| [26] |

Y. He, J. Cai, L. Zhang, et al., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53 (2014) 5905-5915. DOI:10.1021/ie4043856 |

| [27] |

L. Jing, Y. Xu, J. Liu, et al., Appl. Catal. B 277 (2020) 119245. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119245 |

| [28] |

S. Wang, T. He, P. Chen, et al., Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) 2001385. DOI:10.1002/adma.202001385 |

| [29] |

S. Wang, B.Y. Guan, X.W. Lou, Energy Environ. Sci. 11 (2018) 306-310. DOI:10.1039/C7EE02934A |

| [30] |

F. Yang, X. Bao, P. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 14179-14183. DOI:10.1002/anie.201908194 |

| [31] |

Y. Wang, C. Zhang, R. Li, Trans. Tianjin Univ. 28 (2022) 227-235. DOI:10.1007/s12209-022-00334-x |

| [32] |

B. Zhang, Y. Chang, Y. Wu, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 12 (2022) 2200321. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202200321 |

| [33] |

W. Wei, Z. Wei, R. Li, et al., Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 3199. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-30958-5 |

| [34] |

W. Zhang, C. Fu, J. Low, et al., Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 2806. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-30532-z |

| [35] |

W. Fan, H. Li, F. Zhao, et al., Chem. Commun. 52 (2016) 5316-5319. DOI:10.1039/C6CC00903D |

| [36] |

Y. Zhao, C. Chang, F. Teng, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 7 (2017) 1700005. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201700005 |

| [37] |

Y. Guo, B. Yan, F. Deng, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107468. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.04.066 |

| [38] |

L. Liu, H. Li, H. Zhou, et al., Chem 9 (2023) 637-649. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2022.10.026 |

| [39] |

X. Yu, V.L. Zholobenko, S. Moldovan, et al., Nat. Energy 5 (2020) 511-519. DOI:10.1038/s41560-020-0616-7 |

| [40] |

Y. Fang, Q. Zhang, H. Zhang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202212273. DOI:10.1002/anie.202212273 |

| [41] |

Y. Zhang, S. Zhao, J. Feng, et al., Chem 7 (2021) 2022-2059. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2021.02.015 |

| [42] |

N. Daelman, M. Capdevila-Cortada, N. López, Nat. Mater. 18 (2019) 1215-1221. DOI:10.1038/s41563-019-0444-y |

| [43] |

J. Di, Y. Li, Y. Zhang, et al., Trans. Tianjin Univ. (2022). DOI:10.1007/s12209-022-00344-9 |

| [44] |

S. Wu, H. Liu, Z. Huang, H. Xu, W. Shen, Appl. Catal. B 312 (2022) 121387. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.121387 |

| [45] |

L. Zhang, Y. Liu, X. Fang, Y. Cheng, Fuel 321 (2022) 124116. DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124116 |

| [46] |

Y. Wang, R. Liu, M. Shi, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107200. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.02.006 |

| [47] |

N. Li, B. Wang, Y. Si, et al., ACS Catal. 9 (2019) 5590-5602. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.9b00223 |

| [48] |

W. Wang, C. Deng, S. Xie, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 2984-2993. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c00206 |

| [49] |

L. Wang, B. Zhao, C. Wang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 8 (2020) 10175-10179. DOI:10.1039/d0ta01256d |

| [50] |

W. Jiang, J. Low, K. Mao, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 269-278. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c10369 |

| [51] |

F. Tian, H. Zhang, S. Liu, et al., Appl. Catal. B 285 (2021) 119834. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119834 |

| [52] |

W. Gao, S. Li, H. He, et al., Nat. Commun. 12 (2021) 4747. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-25068-7 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35