b Innovation Institute of Industrial Design and Machine Intelligence Quanzhou-Hunan University, Quanzhou 362801, China

The number of small-molecule drugs accounts for a significant portion of drugs that are used frequently [1]. Their favorable spatial dispersion and drug-forming qualities also aid in the creation of new drugs [2]. Carboxylic acids (Aspirin [3]), indoles (Indomethacin [4]), benzophenones (Fenofibrate [5]) and sesquiterpenes (Artemisinin [6]) are examples of common small-molecule medications. These medications are widely used as antipyretic, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antiseptic. Small-molecule drug industrial synthesis techniques currently used are fairly advanced, but some pressing issues still need to be resolved. These issues include non-recyclable catalysts, expensive metal catalysts, and complicated reaction processes [7]. Therefore, a key area for future research and development is the creation of new multiphase photocatalysts for the synthesis of small-molecule drugs or drug precursors [8].

The use of photocatalysis to transform solar energy into chemical energy is one of the methods for preserving and using solar energy, and it has received extensive research [9]. In the process of photocatalysis, photocatalysts adsorb photons to produce electrons and holes [10] and carriers that separate and spread to the surface of the photocatalyst [11] to start redox reactions. Carbon dioxide reduction [12] and organic matter oxidation [13] are typical photocatalytic processes. The benefits of photocatalytic organic synthesis over traditional techniques include high selectivity, environmental tolerance, and mild reaction conditions [14].

The evolution of photocatalysis depends on the variety of photocatalyst kinds. The tunable structure, high porosity, and sizable specific surface area of porous framework materials enable them to function exceptionally well as catalysts in multiphase photocatalysis. To speed up the reaction process, porous framework materials can be structurally engineered to adjust to the size of the reactant and alter the microenvironment around the catalytic site. They can also accurately alter the ligand structure and electronic state of the catalytic site to enhance catalytic performance [15]. As a result, photocatalysts in the class of porous framework materials have tremendous potential.

2. Synthesis of porous framework materialsCoordinated-driven self-assembly provides a favorable approach for fabricating organometallic structures with a variety of structures and functions. As is known to all, the size and form of the photocatalyst light catalytic properties play an important role. Therefore, it is of great importance to find an effective method to prepare porous organic framework photocatalysts with controllable size and structure.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are made by metal and organic ligand coordination way form the frame structure. The solvothermal method is widely considered to be an effective approach for the synthesis of MOFs due to its straightforward operation, mild reaction conditions, and ability to promote the production of MOFs with high yields [16]. The most important thing in the process of solvothermal reaction is to choose the right solvent. At present, the organic solvents used for the preparation of MOFs are N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) [17], dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [18], N,N-diethylformamide (DEF) [19], toluene, etc. These organic solvents are used as structural guidance agents and synthetic media in the synthesis process. In addition, various methods such as hydrothermal reaction, solution precipitation, ultrasonic, microwave, oil bath, and template methods can be used to prepare high quality MOFs.

Generally, covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are built from organic building blocks via reversible condensation reaction. The connections within the COFs lattice can be understood as continuous correction and rearrangement, resulting in a crystal structure rather than an amorphous state. Since the first successful synthesis of COFs by solvothermal method, this method has been widely used in the synthesis of COFs [20]. In solvothermal synthesis, the required monomers, solvents and catalysts are placed in sealed containers such as sealed tube, ampule, glass bottle with cap, or Teflon lined stainless autoclave. At present, the synthesis methods of COFs include solvothermal, ball milling [21], microwave [22], sonochemical [23] and ionothermal [24] method.

The synthesis of discrete porous coordination cages (PCCs) structures is typically achieved by coordination-driven self-assembly of metal ions and organic ligands in a specific solution through the use of a "bottom-up" approach. Typical methods of PCCs synthesis include classical solution reaction and solvothermal synthesis [25]. In recent years, advanced post-synthetic modification methods have gained recognition because it is more dynamic than traditional methods [26]. Predicting the synthesis of PCCs is therefore a difficult challenge. Changes in reaction conditions, even subtle changes, can lead to significant differences in PCCs.

For porous organic frames, with different synthesis methods, the structure of the frame will be changed to a great extent, and the crystal structure of different packing and coordination modes will be obtained. Even under the premise of obtaining the same crystal structure, it is still possible to obtain materials of different sizes, different yields and different shapes, which indirectly affects their performance as photocatalysts and the efficiency of synthesis of small molecule drugs. For example, size and shape may affect the catalytic effect due to the different surface area of the material.

3. Common photocatalytic reactions of porous framework materialsConventional photocatalysts, commonly use small molecule metal complexes, such as ruthenium and iridium complexes [27]. Although these catalysts have excellent photophysical properties, they are costly, toxic, and prone to environmental pollution [28]. Organic photocatalysts, such as rhodamine B and eosin Y, have recently been introduced into the photocatalytic process to replace small molecule metal complexes [29,30]. Although organo-catalysts can achieve comparable or even better catalytic efficiency [31], their synthesis is often accompanied by pollution [32].

Compared with inorganic porous materials, the biggest advantage of organic porous frame materials is that the arrangement of the frame can be accurately regulated. Porous organic frame materials facilitate the control of the structure and function of the target material by building units. The building units are small organic molecules, which come from a wide variety of sources and make the building units diversified. At the same time, it is connected by covalent bonds to form a spatial network structure, which has good thermal and chemical stability.

MOFs, COFs, PCCs are typical porous framework materials. They all have lots of active sites, adjustable pore channels, and a sizable specific surface area. They have excellent catalytic properties as a result of these features [33]. In addition, MOFs, COFs and PCCs differ in terms of photocatalysis. MOFs is composed of metal ions or clusters connected with organic ligands through coordination bonds, which has better structural adjustability. For different catalytic reactions, MOFs can be easily modified with corresponding active groups during synthesis, and different materials can also be loaded as photocatalysts through post-modification [34]. COFs are formed from organic monomers connected by covalent bonds, and their structure is more stable, which is more suitable for catalytic reactions under severe reaction conditions. As a discrete structure, PCCs have independent cavities. When it is used as a photocatalyst, the reaction substrate can be confined to the interior of the cage to obtain products of different conformations. This also offers guidance for addressing the energy crisis and environmental issues [35] brought on by traditional organic conversion techniques. In conclusion, we started by listing the uses of these three common porous framework materials in photocatalysis.

3.1. Photocatalytic reaction of MOFsThe distinct benefits that MOFs photocatalysts [36] show in photocatalytic reactions have been widely acknowledged [37] in previous papers. For instance, several active sites, a large number of desorption channels, and various charge transfer paths in photocatalytic processes [38,39]. By structural regulation and control, MOF photocatalysts may also accelerate charge separation and transfer rates [22], and the high porosity also enriched the light absorption sites to increase the light absorption capacity.

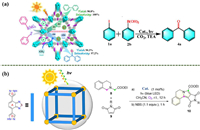

In 2021, Lin’s group designed a bifunctional metal-organic layer (MOL) utilizing metalized organic ligands and Hf6 that had been triflate-capped. The authors have achieved the first efficient conversion of hydrocarbons to cyan-alcohol using MOF(1)-Fe and styrene to styrene carbonate using MOF(1)-Mn through metal center modulation. This work solves the problem of incompatibility between the two by immobilizing different catalysts in layers onto a solid carrier (Fig. 1a). At the same time, MOL can integrate synergistic catalytic sites to provide reusable solid catalysts for tandem reactions, highlighting the potential of structurally tunable porous framework materials for photocatalytic applications [40].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (a) MOLs with both metal sites and Lewis acid sites for photocatalysis. Copied with permission [40]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (b) Chemical structures of Zr6 8-c, H4L, H2TCPP(Ni) and Zr6 12-c. Formation and topological representations of MOF(2), MOF(2)-Ni (C, gray; O, red; N, blue; Zr, cyan polyhedra). Reproduced with permission [41]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (c) Synthetic route of MOF(3) and its selective photocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide to methane. Reproduced with permission [42]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH GmbH. (d) Under visible light irradiation, MOF(4)-Fe can convert nitrogen to ammonia. Copied with permission [44]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. | |

Meanwhile, Energy transfer, or EnT, is a crucial mechanism in nature, and much research has been done to mimic how photosynthesis works. 2-H2TCPP, a metal-organic framework with high porosity and photoactivity, was created and synthesized by Zhang’s group. In MOF(2), the organic ligand H2TCPP is precisely attached to the open metal sites of the octahedral cage. Time-resolved spectroscopy is used to track the EnT conversion of N,N’-bis-carbazole to porphyrin in the compound. 2-H2TCPP further showed outstanding catalytic activity in the photocatalytic oxidation of thioanisole. A hybrid ligand MOF was successfully constructed using two geometrically distinct tetrahedral N,N’-bis-carbazole, and a square planar porphyrin-based ligand (Fig. 1b). The size and shape of the equatorial plane of the octahedral cage in MOF(2) closely match those of the photoactive porphyrin ligand H2TCPP. This leads to an ideal assembly of the donor-acceptor structure, which facilitates light harvesting and energy transfer [41].

The science of mimicking natural photosynthesis to seize CO2 and transform it into high-value compounds is being extensively researched. As a result, Yun’s group created a technique for encasing Cu2O nanowires in MOF. The process uses a synthetic substance to selective photocatalysis the conversion of CO2 to CH4 without the need for surfactants. This study extends the understanding of the relationship between MOF(3) and metal oxides and goes beyond their traditional physisorption/chemisorption type interactions (Fig. 1c). These findings will favorably support the development of efficient organic-inorganic crossover photocatalysts in the future [42].

What is more, ammonia (NH3) plays a vital part in the production of pharmaceuticals and other goods used in industry [43] as a crucial chemical raw material and carbon-free energy carrier. The very stable MOF(4)-Fe was put together by Liang’s group, with Fe serving as the metal center and Al serving as the metal node for the photoactive ligand porphyrin. The active center of photocatalysis, according to the authors, is the Fe-N site. This work achieved room-temperature nitrogen fixation under visible light conditions (Fig. 1d). The dispersed active Fe acts as a trapping site for photogenerated electrons and inhibits electron-hole complexation, effectively enhancing N2 adsorption and activation [44]. It provides a reference for the rational design of artificial photosynthesis catalysts.

Therefore, MOF photocatalysts can be constructed by choosing organic ligands with one/multiple photocatalytic activities, constructing dual metal sites on ligands [45], loading oxide materials onto MOFs, etc. All these strategies can lead to efficient photocatalytic conversion of MOF materials.

3.2. Photocatalytic reaction of COFsCOFs are an emerging family of porous framework materials that have extended π-conjugation, excellent stability, and pre-settable structures [46]. These characteristics aid in the transit and isolation of electron holes during photocatalytic reactions and offer good catalytic performance for processes including redox [47], ring formation [48], and polymerization [49]. Materials made from COFs have potential uses as non-homogeneous metal-free photocatalysts.

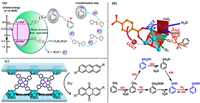

To make full use of the π-conjugated structure to enhance the stability of COFs, Wang’s group constructed a series of super-stable benzoxazole-based COFs by a "two birds with one stone" strategy. The optical band gap can be lowered and visible light absorption improved by adding benzoxazole structures to COF(5). The oxidative hydroxylation of aryl boronic acids, which is triggered by visible light, serves as an outstanding example of this material’s remarkable photocatalytic properties (Fig. 2a) [50]. By this method, the construction of super-stable structures and the functionalization of metal-free photocatalysis were achieved simultaneously. Recently, similar methods for building COFs materials have been reported [51].

Moreover, a unique 2D-COF, exhibits a significant permanent porosity of pores and a high specific surface area. The oxidation of C—H bonds served as evidence of the material’s superior photocatalytic abilities. In the cross-dehydrogenation coupling (CDC) reaction of N-aryl tetrahydroisoquinoline, it was demonstrated to have outstanding catalytic properties [52]. Most COFs materials may catalyze effectively in mild circumstances in other traditional photocatalytic oxidation reactions such as thioanisole oxidation [53], benzylamine coupling [36], and benzyl alcohol oxidation [54].

Dimensionality allows for fine-tuning of the solid material’s electrical structural features. Studies on the impact of various dimensions on the photocatalytic performance of COFs materials are currently lacking. As a result, Cui’s group designed a novel N-diaryl dihydro phenazine (PN) building block and made six isomorphic COF(6)-2D and one COF(6)-3D (Fig. 2b). This is attributed to the two-dimensional structure with a larger internal surface area, more catalytic active sites, higher photosensitivity, and photoinduced electron transfer efficiency [49].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) The photocatalytic conversion of aryl boronic acids to phenols in the presence of COF(5) involves the SET (single-electron transfer) mechanism. Reproduced with permission [50]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. (b) Application of COF(6)-2D and COF(6)-3D with higher internal surface area for the photocatalytic polymerization reaction. Copied with permission [49]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH GmbH. | |

The rational construction of COFs structure mainly relies on the reversible formation of covalent bonds between components, and further improvement of their structural robustness is crucial for their practical applications [55]. High specific surface area and large porosity are also common features of COFs materials with high photocatalytic ability. In addition, dimensionality is a fundamental parameter to modulate the properties of solid materials by tuning the electronic structure. The microstructure, surface area, and electron density of COFs are closely related to the dimensionality, so tuning the dimensionality of materials has an important impact on photocatalytic performance.

3.3. Photocatalytic reaction of PCCsDue to their distinct structural characteristics and catalytic activity, porous ligand molecular cages make the perfect platform for green catalysis [56]. The guests can bind to the independent cavity of the molecular cage, which raises the concentration of the local substrate and improves catalytic performance. It has been demonstrated that the cavity of the molecular cage regulates the activity and selectivity of guest photocatalytic redox, including C—H bond activation [57], Byanamine coupling [58], reduction processes [59], and [2+2] cycloaddition [60]. In addition, molecular cages can have their dimensions, shapes, metal centers, and ligand characteristics customized. Porous coordination molecular cages are a great class of photocatalysts because of this.

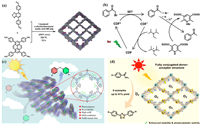

Inspire by the enzyme, Dasgupta’s group created a sp3C-H bond oxidation reaction pathway using guest charge transfer. Entering the cage(7) cavity, the electron-rich visitor creates photoactivatable host-guest charge-transfer complexes. The structural characteristics of the molecular cage in the catalytic system increase the lifetime of the carbon radicals, which effectively interact with oxygen molecules and form oxidation products with high selectivity [57]. This work uses the light energy absorbed by molecules to activate chemical bonds at a very fast rate, elucidating the key role of charge in driving reactions at nanometer confinement (Fig. 3a). Thereby, it is hypothesized that tailored charge signatures should be able to trap complex molecules within molecular cages and enable selective bond polarization.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) Strategy for rapid C—H bond activation and photooxidation in water. Copied with permission [57]. Copyright 2019, The Authors. (b) 1H NMR spectra (400 MHz, D2O/CD3CN = 5:1,298 K) for a photooxidation process. (1) W10O32⊂cage(8); (2) (4-bromotoluene + W10O32)⊂cage(8); (3) after irradiation; (4) product in CDCl3; (5) 4-bromotoluene. Reproduced with permission [61]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH GmbH. | |

In 2022, Sun’s group designed a novel water-soluble cage(8) material by employing dynamic macrocyclic ligands to self-assemble. This substance’s adaptive self-assembly results in appropriate guest binding and catalytic activities. Cage(8) was used to enclose electron-rich polymetallic oxygenate clusters (W10O324−) and toluene derivatives (Fig. 3b). They selectively photo-oxidize C—H to aldehyde compounds in benign conditions [61]. This work uses an enzyme-like concept to complement the substrate with the cavity, providing a convenient strategy for coordinated-driven self-assembly to build metal cages.

For massive metal cages with well-defined cavities, most of them are constructed from rigid ligands to ensure symmetry of the assembly process. Correspondingly, flexible ligands usually produce interconverted structures, accompanied by the collapse of the cavities. However, rigid molecular cages are not conducive to catalysis due to the requirement of cavities for the products during the reaction. Therefore, a balance between the flexibility of the ligand conformation and the expected cavity needs to be considered in the construction of novel molecular cages as a way to synthesize highly adaptable building blocks and porous ligand molecular cages.

As heterogeneous catalysts, MOF materials are highly stable, and the metal core can serve as the catalytic active site. Additionally, the abundant pore structure can enhance substrate adsorption and desorption effectiveness and further the reaction process. As covalently bonded porous materials, COF materials have a unique advantage in the synthesis of small molecule drugs because they can avoid metal residues in the catalytic process in addition to having good stability and an abundance of pores. Although metal ions and organic ligands coordinate to create PCC materials, just like MOFs, PCC materials form discrete polyhedral materials with distinctive cavity structures in the presence of vertex ligands. PCC materials can operate as both heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysts in a reaction because of their distinctive spatial structure. The three materials have numerous advantages over conventional small molecule catalysts, including the ability to be recycled during catalytic reactions and the ability to produce heterogeneous catalysis by enriching substrates with a lot of pore structure.

4. Photocatalytic synthesis of small-molecule drugs by porous framework materialsThere are still some inevitable issues with the present industrial synthesis techniques for familiar small-molecule medications. For instance, metal residual, more by-products, unfavorable reaction conditions. One area for future development is the use of photocatalytic organic conversion in industrial production, which may transform light energy into different types of chemical energy [62,63]. Moreover, the current reports demonstrated remarkable catalytic activity in the photocatalytic production of small-molecule medicines using porous framework materials.

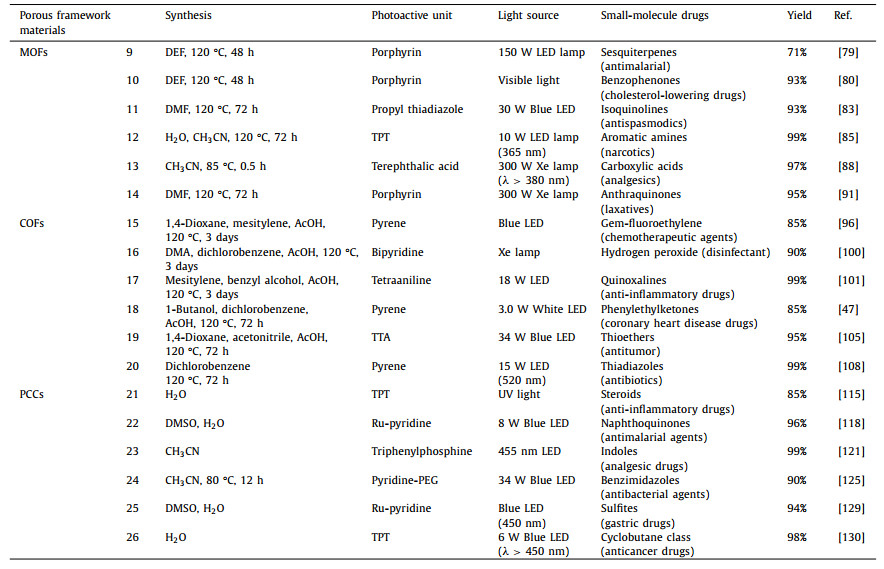

It is well known that MOFs, COFs and PCCs, as porous framework materials, have the advantages of high specific surface area and structural adjustability, and are all considered to be excellent photocatalysts at present (Table 1). At the same time, the three have different advantages for different small molecule drug synthesis. In general, MOFs have better structural adjustability. For different catalytic reactions, it is easy to modify the corresponding active groups during the synthesis of MOFs, and different materials can be loaded as photocatalysts by post-modification [64,65]. COFs with photocatalytic activity are composed of small organic molecules with different functions as electron donors or acceptors through covalent bonding. The ordered constructed D-A system allows charge transfer from donor to acceptor, due to the extended delocalization in the conjugated structure [66,67]. Its more stable frame structure is more suitable for the synthesis of small molecule drug reactions under severe synthesis conditions. As a discrete structure, PCC can be used as a photocatalyst to confine the reaction substrate to the interior of the cage and obtain products of different conformations by limiting molecular rotation.

|

|

Table 1 Recent advances in porous framework materials for the synthesis of small-molecule drugs. |

Despite the advanced industrial synthesis techniques of small molecule drugs currently in use, there are some pressing problems with most synthesis methods. The synthesis of small molecule drugs such as antimalarial and antispasmodics requires expensive catalysts. The synthesis of small molecule drugs, such as cholesterol-lowering drugs and chemotherapeutic agents, has very low response selectivity. These problems include non-recyclable catalysts, expensive metal catalysts, and complex reaction processes [68,69]. Therefore, a more effective catalyst should be sought for small molecule drug synthesis.

In recent years, green chemistry and sustainability have become the subject of the development of new synthetic methods. Therefore, a key area for future research and development is the creation of novel multiphase photocatalysts for the synthesis of small molecule drugs or drug precursors. Porous frame materials are favored for their optical properties of combining transition metal complexes and small organic molecules. As a new type of photocatalyst, porous frame materials can further implement the concept of green chemistry. It uses visible light for oxidation and reduction reaction catalysis, which can reduce costs and be recycled, further implementing the concept of green chemistry.

For small molecule drug synthesis, the common photocatalytic processes include the formation of carbon-carbon bond, carbon-nitrogen bond and carbon-oxygen bond. Simple alkyl substituents can change the physicochemical properties of carbon-carbon bond substituents, which has a great impact on the selectivity and yield of drugs. For example, the regionally selective methylation of Fasudil [70]. Forming carbon-nitrogen bonds is a useful strategy for preparing interesting building blocks in medicinal chemistry. It has been reported that the direct α-C-H amination of tetrahydroquinoline and indole produces N,N-acetals. Direct α-C-H amination of tetrahydroquinolines and indolines giving rise to N,N-acetals is reported as a useful strategy for preparing interesting building blocks in medicinal chemistry [71]. Photocatalysis of functionalized drug molecules to form carbon-oxygen bonds is common. 2-Aminobenzoxazole, for example, is an important drug molecular intermediate used to treat diseases such as inflammation and can be synthesized by building carbon-oxygen bonds [72].

Visible light photoredox catalysis has become a mild and effective method for generating free radicals. The reaction rate in photocatalysis is related to the intensity of light. Therefore, photocatalysis provides a favorable tool for controlling the production of free radicals [73]. The mechanism of the photocatalyst (PC) in the reaction is mostly the transformation from the ground state to the singlet excited state under the irradiation of visible light. In addition, due to intersystem crossing (ISC), the strongest PC have a high chance of forming a long-lasting triplet excited state. Intermolecular reactions are usually mediated by ISC excited states, causing additional chemical transitions that often rely on single electron transfer. The photoexcited PC becomes an effective oxidant and reducing agent, giving or receiving electrons. In the reduction system, the photoexcited PC* first acts as an oxidizing agent, trapping electrons from the electron donor to form a PC•− radical anion with a strong reduction potential. In oxidation systems, photoexcited PC* acts as a reducing agent to transfer electrons to electron acceptors. This results in the formation of PC•+ radical cations. The chemical change is also thought to be caused by the energy transfer within the PC from the ground state transition to the excited state [74].

Since photocatalysis is a powerful emerging field of organic conversion, the use of porous frame materials as photocatalysts for the synthesis of small molecule drugs has great potential.

4.2. Photocatalytic synthesis of small-molecule drugs by MOFsCompared with conventional metal catalysts, MOFs not only have active metal centers but also have higher stability [75]. In addition, MOFs offer the advantages of functional designability, graded porosity, and recyclability. These features provide a more efficient method for the synthesis of drugs such as artemisinin [76] and fenofibrate [77].

4.3. Sesquiterpenes (antimalarial)The most efficient medication for treating malaria is sesquiterpene endoperoxide artemisinin, yet current synthesis processes still have poor yields and high costs [78]. As a result, Zhou’s group developed bifunctional catalysts by gluing Brønsted acid sites onto porphyrin-based metal-organic frameworks’ pore channels (Fig. 4). It is an effective catalyst for artemisinin production due to the interaction between the interpenetrating channels and the specifically designed pore environment. Comparing this MOF(9) to traditional homogeneous catalysts, improved levels of selectivity, recoverability, and stability are seen [79].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Using MOF(9) as a photocatalyst, the reaction mechanism of photocatalytic oxidation of dihydroartemisinic acid to artemisinin. Reproduced with permission [79]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. | |

By employing CO2 as a carbon source, Zhang’s team achieved a green synthesis of benzophenone using a new composite catalyst MOF(10) (Fig. 5a). As composite catalysts, the author placed nanoclusters onto metal-organic skeletons based on porphyrin. Synergistic interactions between various components were used to obtain effective catalytic performance [80]. In addition, the authors used a composite catalyst for the synthesis of the cholesterol-lowering medicinal compound fenofibrate under mild conditions [81].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) Highly efficient MOF(10) photocatalyst for solar-driven Suzuki coupling reaction with multiple components under the synergistic action of carbon dioxide or argon gas. Copied with permission [80]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (b) The cartoon picture of MOF(11). Visible-light-driven photocatalytic [3+2] cycloaddition and oxidative aromatization. Reproduced with permission [83]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. | |

The well-known poppy bases are still significant antispasmodics among isoquinolines, which are compounds with a variety of biological activities [82]. In 2021, Li’s group successfully synthesized a new photoactive MOF(11). It was used to synthesize pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline heterocycles, which include pyrrolo[2,1-a], by the [3+2] cycloaddition mechanism (Fig. 5b). The source of the material’s photocatalytic activity in MOF(11) is the organic ligand pyrazole-benzothiadiazole-pyrazole with a D-A-D conjugated system [83].

4.3.3. Aromatic amines (narcotics)An aromatic small-molecule medication that is frequently used as a local anesthetic is procaine [84]. Han’s group designed a MOF(12) with strong redox activity as a result, and they successfully produced arylamines from nitrobenzene using photoreduction. The band gap energy of the MOF(12) is average, and the photocatalytic activity of the substance is improved by the π-π stacking interactions between TPTs. Additionally, the D-π conjugation of the ligand and Cu(Ⅰ) encourages the activity to rise (Fig. 6a). The synergistic effect of the two results in efficient hole-electron separation and ordered electron transfer [85].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. (a) A hypothetical reaction mechanism is proposed for the photoreduction of nitrobenzene. Reproduced with permission [85]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (b) Turning on visible-light photocatalytic C−H oxidation by MOF(13). Copied with permission [88]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (c) MOF(14) acts as a heterogeneous catalyst for the catalytic oxidation of anthracene to anthraquinone. Reproduced with permission [91]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH GmbH. | |

The photocatalytic carbonylation procedure using CO2 as a carbon source to produce small-molecule analgesics like aspirin [86], ibuprofen [87], and others that contain carboxylic acids is still a difficult task. Therefore, Jang’s group developed a new MOF(13) and successfully applied it to activate stubborn C—H bonds (Fig. 6b) [88]. In MOF(13), photogenerated electrons can reduce O2 to the O2•− radical, and the corresponding hole oxidizes H2O to the ·OH radical. The ·OH radicals make toluene dehydrogenate to form benzyl radicals. Benzyl radicals accept ·OH to produce benzyl alcohol and subsequent benzaldehyde. In addition, phenyl radicals can also form benzaldehyde under the action of O2•−. Under the action of ·OH and O2•− free radicals, the final product benzoic acid was obtained.

4.3.5. Anthraquinones (laxatives)Anthraquinones [89] have hemostatic, antibacterial, laxative, and hemostatic properties. It is often used as a laxative in the treatment of chronic constipation [90] and other diseases. Zhou’s group achieved the functionalization of MOL by a one-pot synthesis strategy, which provides an ideal platform for the selective oxidation of anthracene. By adding a secondary ligand column to the Zr6-BTB layer, the metal-phthalocyanine fragment was successfully incorporated into the MOF(14) (Fig. 6c). This method differs from the traditional anthraquinone synthesis in that it does not call for highly toxic oxidants, high pressure, or high temperatures. Hence, it creates an effective and environmentally friendly synthesis strategy [91].

In summary, we found that the tunable properties of MOFs are fully utilized to construct photoactive materials with excellent photocatalytic properties [92]. These materials can be used as excellent photocatalysts to synthesize molecules such as sesquiterpenes, benzophenones, isoquinolines, aromatic amines, carboxylic acids, anthraquinones. Most importantly, small-molecule drugs such as antimalarial, cholesterol-lowering drugs, antispasmodics, narcotics, analgesics, laxatives, can be prepared based on the above photocatalytic reactions.

4.4. Photocatalytic synthesis of small-molecule drugs by COFsCOFs, an emerging class of crystalline nanoporous framework materials, have extended conjugated and ordered porous structures [93]. These characteristics result in excellent visible light absorption and facilitation of electron-hole transfer. Furthermore, the structure and function of COFs can be tuned in a controlled manner using pre-designed molecular junctions. Therefore, COFs materials have greater advantages over inorganic semiconductors in photocatalysis [94].

4.4.1. Gem-fluoroethylene (chemotherapeutic agents)The gem‑difluoro methylene group is an important fluorinated moiety. It is widely present in bioactive and pharmaceutical molecules, including Maraviroc (HIV-1 therapeutic agent) and Gemcitabine (chemotherapy drug) [95]. Therefore, Beyzavi and coworkers synthesized an imine COF(15) with a highly High crystallinity double pore structure (Fig. 7a). In the bigger pores, the metal coordinates with the imine and pyridine N. The material exhibited excellent photocatalytic properties in the Decarboxylative difluoro alkylation reaction after loading Pt [96].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. (a) Proposed mechanism of the decarboxylative difluoro alkylation process. Reproduced with permission [96]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (b) COFs and APs were tested for their photocatalytic activity in H2O2 production from water and air at 298 K. Chemical structures and photocatalytic performance were analyzed, including (1) COF(16)-TfpBpy, (2) COF(16)-TfpBd, (3) COF(16)-TfpDaaq, (4) COF(16)-TfpPa, (5) COF(16)-TfpBpy-Mo, (6) AP-TfpBpy, and (7) AP-TfbBpy. Reproduced with permission [100]. Copyright 2022, The Authors. Angewandte Chemie International Edition published by Wiley-VCH GmbH. (c) Comparison of H2O2 photocatalytic rates of amorphous polymer photocatalysts and different COFs. Reproduced with permission [100]. Copyright 2022, The Authors. Angewandte Chemie International Edition published by Wiley-VCH GmbH. (d) The proposed mechanism of 1,3-dicarbonyls for the α-examination. Copied with permission [102]. Copyright 2021, Science China Press and Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature. | |

H2O2 solution can be used directly for contaminant removal [97] and water disinfection [98], and when used as an eco-friendly disinfectant to inactivate pathogenic microorganisms, it does not pollute the environment secondarily [99]. To achieve even more efficient photocatalytic synthesis of H2O2 on a small scale, Ma and coworkers synthesized a catalyst, COF(16), that enables efficient photocatalytic production of H2O2. It was found that no sacrificial agent or stabilizer was required in this reaction (Figs. 7b and c). The protonation of the nitrogen atom in the bipyridine monomer facilitated the generation of intermediates via 2e− pathway [100]. This work provides a direction for the efficient synthesis of H2O2 on a small scale.

4.4.3. Quinoxalines (anti-inflammatory drugs)In the production of the anti-tuberculosis medication pyrazinamide, quinoxalines are utilized as intermediates and reagents in organic synthesis. The synthesis of quinine, which has anticancer and anti-inflammatory effects, using the oxidative amination products of carbon-based compounds is one of the key techniques for making such small-molecule drugs [101]. Inorganic photocatalysts for these processes are currently being developed, however, they still have issues with high toxicity, poor cycling stability, and low recovery rates. Therefore, three new COFs materials with high crystallinity, large porosity, and excellent stability were synthesized by Chen’s group in 2021 using the solvothermal method (Fig. 7d). COF(17) have a smaller band gap (1.96 eV) and a more negative HOMO value (−5.97 eV), which makes them better photocatalysts for the oxidation of α-carbon-based compounds [102].

4.4.4. Phenylethylketones (coronary heart disease drugs)Acetophenones have a wide range of applications in antibacterial and anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antioxidant applications [103]. Liu’s group reported a novel imine-based covalent organic framework and applied it to the reductive dehalogenation reaction of bromobenzene derivatives (Fig. 8a). This new COF(18) has a unique electron donor-acceptor structure, excellent visible light absorption, and good photoelectric response properties (Fig. 8b). Therefore, it exhibited efficient catalytic performance in the reduction of 2-bromoacetophenone to acetophenone [47].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 8. (a, b) The synthesis of COF(18) via imine condensation and its proposed mechanism for photoreduction dehalogenation. Reproduced with permission [47]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. (c) COF(19) as photocatalyst for the synthesis of thioether. Copied with permission [105]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH GmbH. (d) Possible photocatalytic pathways for COF(20) catalyzed oxidative amine coupling and thioamide cyclization to form 1,2,4-thiadiazoles. Copied with permission [108]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. | |

In 2021, Leus and coworkers synthesized a triazine COF(19) with a single Ni site as a dual catalyst and successfully applied it to photocatalytic C-S bond cross-coupling reactions. This also provides a platform for the synthesis of sulfur-containing small-molecule drugs, such as 6-mercaptopurine [104], a drug with antitumor activity (Fig. 8c). This research shows that the material has a narrower band gap due to the addition of the electron acceptor triazine ligand, and it also shows the dual catalytic ability that results from the introduction of a single metal site in the photosensitive COF(19) framework [105].

4.4.6. Thiadiazoles (antibiotics)Thiadiazoles [106], a subfamily of azoles, contain a five-membered heterocyclic ring consisting of C, N, and S in their structure and are important intermediates for the synthesis of the antibiotic drug cefazolin sodium [107]. A COF material with a D-A structure was reported by Wang’s group. It showed a powerful light-driven organic synthesis in the photocatalytic thioamide cyclization reaction for the synthesis of 1,2,4-thiadiazoles [108]. The fully conjugated D-A type COF(20) material has high stability and charge separation ability, and also can effectively generate superoxide radicals to promote the reaction under visible light irradiation (Fig. 8d). In 2023, a COF material with a D-A heterostructure was constituted by the group of Xiaojun Wang using the same method. They also successfully applied it to the reaction for the photocatalytic synthesis of 1,2,4-thiadiazole by thioamide [48].

Herein, we found that COFs with a D-A structure have higher stability and charge separation ability. COFs materials with photogenerated electron capabilities can synthesize molecules such as gem‑fluoroethylene, H2O2, quinoxalines, phenylethylketones, thioethers, thiadiazoles. by photocatalysis. In addition, small molecule drugs such as chemotherapeutic agents, disinfectants, anti-inflammatory drugs, coronary heart disease drugs, antitumor drugs, can be prepared on the basis of the above photocatalytic reactions.

4.5. Photocatalytic synthesis of small-molecule drugs by PCCsPorous coordination molecular cages are discrete structures obtained by the coordination of metal ions and organic ligands to mimic the enzymatic structures in nature [109]. These molecular cages have a single well-defined cavity [110] and suitably sized guests can enter the cavity by dynamic exchange [111]. The cavities of PCCs also serve to increase the local concentration of substrates in the reaction and stabilize reactive intermediates and reactive radical species [112]. In addition, PCCs can be designed with components to achieve specific functions and the same topology makes it easier to study the conformational relationships of the materials. For example, PCC with photocatalytic activity can be constructed by using photoactive ligands, which can improve photocatalytic activity and accomplish selective catalysis [113]. The discrete structure of PCCs allows them to participate in reactions as both homogeneous and inhomogeneous catalysts, which also provides a favorable platform for the photocatalytic synthesis of small-molecule drugs.

4.5.1. Steroids (anti-inflammatory drugs)Steroids, such as glucocorticoids, have powerful anti-inflammatory effects and are among the common drugs used to treat chronic inflammatory diseases [114]. Fujita’s group developed a method of demethylation using the cavity of a photoactive ligand molecular cage(21) (Fig. 9a). This method allows the synthesis of completely new non-natural steroid molecules through electron transfer between an electron-rich guest and a highly electron-deficient molecular cage, resulting in a reaction with remarkable selectivity and yield [115].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 9. (a) Presentation of the demethylation reaction of a putative reaction mechanism. Copied with permission [115]. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. (b) The chiral coordination space in the cage(22) is created by self-organization of homochiral photo redox-active RuL3 metal ligands and Ru/Pd PHE units, enabling unique selectivity in the photoinduced biaryl coupling of 3 to give 4. Reproduced with permission [118]. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. (c) Aggregated Pt(Ⅱ)-based octahedral cage(23) catalyzes the photocyclization of alkynyl anilines, mimicking bio-enzyme catalysis by aggregated biological macromolecules. Copied with permission [121]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. | |

Naphthoquinones [116] are widely used as additives for antibacterial purposes, among which atovaquone [117] is a common naphthoquinone that targets the mitochondrial cytochrome of Plasmodium. Su’s group used the heterometallic molecular cage(22) to achieve photo-induced regioselective and enantioselective coupling of naphthoquinones, resulting in simple and efficient access to naphthoquinones (Fig. 9b). This is due to the restricted coordination space within the heterometallic molecular cage that gives it photo-redox ability and stereoselectivity [118].

4.5.3. Indoles (analgesic drugs)Indoles and their derivatives have very important biological and pharmacological activities as well as excellent anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects [119], and the main common indoles are indomethacin and acemetacin [120]. Duan’s group chose organic ligands with propeller conformation and platinum ions to obtain platinum octahedral cages(23) with restricted cavities by self-assembly. The photocatalytic synthesis of 2-phenylpropanolamine derivatives into indole-like products was achieved [121]. The platinum octahedral cage can aggregate to form larger size structures upon the addition of poor solvents (Fig. 9c). Compared with the primary structure, it has superior substrate binding ability, stronger luminescence, and an excited state lifetime, thus facilitating photocatalytic reactions.

4.5.4. Benzimidazoles (antibacterial agents)Benzimidazoles [122,123] are regarded as a promising class of bioactive scaffolds with diverse activities such as anti-inflammatory, antihelminthic, antimalarial, antimicrobial, antiviral, and anti-mycobacterial [124]. In 2023, Li’s group successfully constructed a class of water-soluble metal supramolecular cages with octahedral structures [125]. Water-soluble metal supramolecular cage(24) have a wide range of applications in the fields of molecular recognition, bionic catalysis, and drug delivery (Fig. 10a). Among them, this class of nanoreactors based on ligand-driven self-assembled constructs mediating photochemical reactions in the aqueous phase has also been reported successively. Its hydrophobic cavity can be used as a nanoreactor to mediate photocatalytic cross-dehydrogenation coupling reactions with benzimidazole as a substrate for post-modification addition. This study enriches the types of chemical reactions that can be achieved with water-soluble metal supramolecular cages.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 10. (a) Water-soluble metal supramolecular compounds for mediating visible-light promoted cross-dehydrogenative coupling reactions. Copied with permission [125]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. (b) Photoactive supramolecular nanoreactor for cage-confined catalysis. Copied with permission [129]. Copyright 2020, The Author(s). (c) Cage(26) for photocatalytic oxidation of anisotropies. Reproduced with permission [131]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. | |

Sulfoxide compounds [126] play a pivotal role in proton pump inhibitors, which occupy a large market of gastrointestinal drugs [127]. Therefore, the synthesis of sulfoxide small-molecule drugs is of great social value. Sun’s group used the synthesized Pd4L2-type molecular cage to achieve selective oxidation of thioether in the aqueous phase. The authors took advantage of the large hydrophobic cavity of the molecular cage to increase the solubility of the substrate in water, while the increase in the local concentration of the substrate also increased the effective collision of the substrate molecules. The two synergistic effects led to the reaction to obtain the sulfoxide product in excellent yields [128]. In 2021, the group also synthesized a biomimetic water-soluble molecular cage(25) that can induce adaptive structural changes in the substrate after binding it (Fig. 10b). The desired conversion and product selectivity can be efficiently achieved through the transformability of the catalyst and the hydrophilicity of the sulfoxide product [129].

4.5.6. Cyclobutane class (anticancer drugs)Organic compounds containing tetradentate rings are a unique class of metabolites that are mainly found in several natural products and drugs. A large number of cyclobutyl compounds have shown antimicrobial, antibacterial, anticancer, and other biological activities, and it has been applied in the synthesis of the anticancer drugs carboplatin and cisplatin [130]. To explore the efficient synthesis of tetrameric cyclic organic compounds, Su’s group synthesized a purely chiral metal-organic cage that facilitated the [2+2] cycloaddition reaction of acenaphthene derivatives under mild conditions. The method achieved the goal of triplet state sensitization and chiral control with the help of the supramolecular confinement effect and achieved stereoselectivity, regioselectivity, and enantioselectivity in the sense of supramolecular catalysis [60]. Subsequently, Su and co-workers synthesized a novel metal-organic cage(26) with a nano spatially restricted domain (Fig. 10c). The [2+2] cycloaddition reaction between molecules of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds was achieved by controlling the conformation of reaction intermediates through its spatially restricted effect. This method has exceptional and efficient diastereoisomeric selectivity [131].

Porous frame materials exhibit remarkable catalytic performance in the production of several small molecule medicines due to their distinctive structural features. Porous framework materials provide high conversion, catalytic cycle performance, and product selectivity throughout the small molecule drug manufacturing process. Porous frame materials provide significant advantages over conventional metal catalysts, but there are also some glaring drawbacks. For instance, MOF materials have good stability, but there is still a chance that some exposed metal sites will come off and leave trace metal residues behind throughout the reaction process. Although the issue of metal residues in the reaction process is avoided by COF materials, the synthesis of ligands and materials is relatively challenging, and there are only a limited number of bonding modes. As both heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysts, PCC materials are difficult to recover in catalytic reactions with certain solvents. Additionally, the stability of PCC materials is attributed to their coordination mode, which is susceptible to acid and alkali influence.

5. Conclusions and prospectsThe fine design and modulation of catalysts play a crucial role in the development of catalysis [132]. As we know, photocatalytic organic synthesis, as one of the most promising applications of porous framework materials [133], has been widely studied by researchers and many research results have been achieved.

The development of photocatalysts with the advantages of low cost, high activity and selectivity, easy recovery, and excellent recyclability is still an active research area [134]. In the exploration of photocatalytic organic transformations, the catalytic sites are mainly constructed by adjusting the structure and composition of the materials, and then the catalytic properties are investigated [135]. The types of reactions using porous framework materials as photocatalysts have expanded to include oxidation, reduction, coupling, cyclization, polymerization, and asymmetric catalysis. Therefore, the exploration of porous framework materials for the photocatalytic synthesis of small molecule drugs is also developing rapidly. With the development of science and technology, our research on the photocatalytic properties of porous framework materials has become more in-depth, which also provides important support for the design and synthesis of small-molecule drug photocatalysts.

Although great progress has been made in the field of porous framework materials as photocatalysts for the synthesis of small molecule drugs, many problems and challenges remain. There are still few types of reactions catalyzed by porous materials as photocatalysts. The reaction yield of the photocatalytic products obtained was not high. The synthetic steps of some functional organic ligands are complicated, which leads to the increase of the cost of frame materials. There are still uncertainties in the synthesis of frame structures, and it is not possible to design and synthesize materials accurately. Some frame structures have poor cyclic stability. The structure-activity relationship between frame structure and photocatalytic properties has not been studied deeply enough.

Therefore, how to develop new organic ligands that are cheap, mild, and environmentally friendly; how to find organic transformation types that can be converted into high value-added chemicals; how to expand the photocatalytic reaction library; how to improve the reaction efficiency; how to reduce the cost of materials; how to study the relationship between framework structure and performance; and how to explore the optimization of the combination between monomer structures relying on artificial intelligence [136] are waiting to be studied and solved.

For porous organic frames, in addition to MOFs, COFs and PCCs described in this review, there are POCs and HOFs and other porous frame materials. POCs are often used in the study of fluorescence properties and guest encapsulation. HOFs are commonly used for gas separation and storage, drug delivery, and sensing. However, POCs and HOFs are rarely used in the field of photocatalysis.

Therefore, we should develop new organic ligands that are cheap, gentle and environmentally friendly. It is also important to find the types of organic transformations that can be converted into high value-added chemicals and how to expand the library of photocatalytic reactions. At the same time, how to improve the reaction efficiency and reduce the cost of materials is the basis of industrial production. Finally, relying on artificial intelligence to explore the combinatorial optimization among monomer structures and the structure-activity relationship between frame structure and catalytic performance is a problem to be studied and solved.

We are very confident that researchers will explore the field of photocatalytic synthesis of small molecule drugs from porous framework materials in a more scientific, rational, and in-depth manner in the future, to realize its practical application in industrial production more quickly.

Declaration of competing interestWe declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, and there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service, and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Nos. 21501133, 22371067), and the China Hunan Provincial Science & Technology Department (Nos. 2020RC3020 and 2021JJ20021).

| [1] |

Y. Lin, Q. Shi, G. Yang, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 120 (2023) e2213670120. DOI:10.1073/pnas.2213670120 |

| [2] |

L.D. Pennington, I. Muegge, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 41 (2021) 128003. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.128003 |

| [3] |

L.M. Hurwitz, P.M. Webb, S.J. Jordan, et al., JAMA Netw. Open 6 (2023) e230666. DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0666 |

| [4] |

K.R. Torres, L.A. Segura, R. Ortíz, et al., ChemistrySelect 7 (2022) e202201897. DOI:10.1002/slct.202201897 |

| [5] |

M. Sabaa, E.L. HM, S. Elshazly, et al., Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 390 (2017) 1061-1071. DOI:10.1007/s00210-017-1407-y |

| [6] |

P. Prawang, Y. Zhang, Y. Zhang, et al., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58 (2019) 18320-18328. DOI:10.1021/acs.iecr.9b03305 |

| [7] |

N. Li, X.P. Zhai, B. Ma, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 11 (2023) 4020-4029. DOI:10.1039/D2TA09777J |

| [8] |

J. Liang, H. Yu, J. Shi, et al., Adv. Mater. 35 (2023) 2209814. DOI:10.1002/adma.202209814 |

| [9] |

L. Candish, K.D. Collins, G.C. Cook, et al., Chem. Rev. 122 (2022) 2907-2980. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00416 |

| [10] |

W. Tu, Y. Zhou, Z. Zou, Adv. Mater. 26 (2014) 4607-4626. DOI:10.1002/adma.201400087 |

| [11] |

H. Tong, S. Ouyang, Y. Bi, et al., Adv. Mater. 24 (2012) 229-251. DOI:10.1002/adma.201102752 |

| [12] |

H. Zhang, Y. Wang, S. Zuo, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 2173-2177. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c08409 |

| [13] |

L. Yang, D. Fan, Z. Li, et al., Adv. Sustain. Syst. 6 (2022) 2100477. DOI:10.1002/adsu.202100477 |

| [14] |

Z.D. Chen, X. Zhou, J.T. Yi, et al., Org. Lett. 24 (2022) 2474-2478. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c00459 |

| [15] |

L. Jiao, J. Wang, H.L. Jiang, Acc. Mater. Res. 2 (2021) 327-339. DOI:10.1021/accountsmr.1c00009 |

| [16] |

B. Lerma-Berlanga, R.G.C.N. Almora-Barrios, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 1798-1806. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c09015 |

| [17] |

X. He, M. Wu, Z. Ao, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 403 (2021) 124048. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124048 |

| [18] |

P.B. So, H.T. Chen, C.H. Lin, Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 309 (2020) 110495. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110495 |

| [19] |

R.A. Dodson, A.P. Kalenak, D.R. Du Bois, et al., Chem. Commun. 56 (2020) 9966-9969. DOI:10.1039/D0CC02741C |

| [20] |

A.P. Co, A.I.O.M. Yaghi, Science 310 (2005) 5751. |

| [21] |

H. Lyu, B. Gao, F. He, et al., ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5 (2017) 9568-9585. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b02170 |

| [22] |

S. Ren, M.J. Bojdys, R. Dawson, et al., Adv. Mater. 24 (2012) 2357-2361. DOI:10.1002/adma.201200751 |

| [23] |

S.T. Yang, J. Kim, H.Y. Cho, et al., RSC Adv. 2 (2012) 10179. DOI:10.1039/c2ra21531d |

| [24] |

M.J. Bojdys, J. Jeromenok, A. Thomas, et al., Adv. Mater. 22 (2010) 2202-2205. DOI:10.1002/adma.200903436 |

| [25] |

E. Martinez-Ahumada, D. He, V. Berryman, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 17556-17563. DOI:10.1002/anie.202104555 |

| [26] |

C. Liu, W. Li, Y. Liu, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 428 (2022) 131129. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.131129 |

| [27] |

C.K. Prier, D.A. Rankic, D.W. MacMillan, Chem. Rev. 113 (2013) 5322-5363. DOI:10.1021/cr300503r |

| [28] |

J.J. Wang, K. Schwedtmann, K. Liu, et al., Green Chem. 23 (2021) 881-888. DOI:10.1039/D0GC03281F |

| [29] |

D. Ravelli, M. Fagnoni, A. Albini, Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2013) 97-113. DOI:10.1039/C2CS35250H |

| [30] |

D.P. Hari, B. Konig, Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 6688-6699. DOI:10.1039/C4CC00751D |

| [31] |

I. Ghosh, L. Marzo, A. Das, et al., Acc. Chem. Res. 49 (2016) 1566-1577. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00229 |

| [32] |

T.K.M.P. Kumar, S.K.A. Kumar, Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 18 (2019) 148-154. DOI:10.1039/c8pp00330k |

| [33] |

J. Guo, Y. Qin, Y. Zhu, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 50 (2021) 5366-5396. DOI:10.1039/D0CS01538E |

| [34] |

X. Liu, X. Yang, X. Ding, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 108148. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108148 |

| [35] |

M.J. Suh, S. Weon, R. Li, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (2020) 9106-9115. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.0c01812 |

| [36] |

G. Wu, J. Ma, S. Li, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 11 (2023) 6747-6771. DOI:10.1039/D3TA00279A |

| [37] |

L. Li, X.S. Wang, T.F. Liu, et al., Small Methods 4 (2020) 2000486. DOI:10.1002/smtd.202000486 |

| [38] |

C.W. Kung, S. Goswami, I. Hod, et al., Acc. Chem. Res. 53 (2020) 1187-1195. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00106 |

| [39] |

L. Chen, Q. Tang, S. Wu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107903. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.107903 |

| [40] |

W. Shi, Y. Quan, G. Lan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 16718-16724. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c07963 |

| [41] |

C. Fiankor, J. Nyakuchena, R.S.H. Khoo, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 20411-20418. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c10291 |

| [42] |

H. Wu, X.Y. Kong, X. Wen, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 8455-8459. DOI:10.1002/anie.202015735 |

| [43] |

C. Guo, J. Ran, A. Vasileff, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 11 (2018) 45-56. DOI:10.1039/C7EE02220D |

| [44] |

S. Shang, W. Xiong, C. Yang, et al., ACS Nano 15 (2021) 9670-9678. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.0c10947 |

| [45] |

Q. Huang, R. Wang, X. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 108517. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108517 |

| [46] |

J. Li, Z. Zhang, J. Jia, et al., Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 38 (2022) 275-289. DOI:10.1007/s40242-022-1434-1 |

| [47] |

Z. Li, Y. Zhi, P. Shao, et al., Appl. Catal. B 245 (2019) 334-342. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.12.065 |

| [48] |

Y. Liu, X. Jiang, L. Chen, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 11 (2023) 1208-1215. DOI:10.1039/D2TA07177K |

| [49] |

K. Wang, X. Kang, C. Yuan, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 19466-19476. DOI:10.1002/anie.202107915 |

| [50] |

P.F. Wei, M.Z. Qi, Z.P. Wang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 4623-4631. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b00571 |

| [51] |

Y. Nailwal, A.D.D. Wonanke, M.A. Addicoat, et al., Macromolecules 54 (2021) 6595-6604. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.1c00574 |

| [52] |

Y. Zhi, Z. Li, X. Feng, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 5 (2017) 22933-22938. DOI:10.1039/C7TA07691F |

| [53] |

Z. Gu, J. Wang, Z. Shan, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 10 (2022) 17624-17632. DOI:10.1039/D2TA04541A |

| [54] |

H. Li, H. Liu, C. Li, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 8 (2020) 18745-18754. DOI:10.1039/D0TA06442D |

| [55] |

P. Shang, X. Yan, Y. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107584. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.06.007 |

| [56] |

R. Ham, C.J. Nielsen, S. Pullen, et al., Chem. Rev. 123 (2023) 5225-5261. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00759 |

| [57] |

A. Das, I. Mandal, R. Venkatramani, et al., Sci. Adv. 5 (2019) eaav4806. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aav4806 |

| [58] |

C. Liu, K. Liu, C. Wang, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 1047. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-14831-x |

| [59] |

H. Lin, Z. Xiao, K.N. Le, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202214055. DOI:10.1002/anie.202214055 |

| [60] |

J. Guo, Y.Z. Fan, Y.L. Lu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 8661-8669. DOI:10.1002/anie.201916722 |

| [61] |

D.N. Yan, L.X. Cai, S.J. Hu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202209879. DOI:10.1002/anie.202209879 |

| [62] |

X. Meng, L. Liu, S. Ouyang, et al., Adv. Mater. 28 (2016) 6781-6803. DOI:10.1002/adma.201600305 |

| [63] |

F. Chen, Y. Zhang, H. Huang, Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107523. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.05.037 |

| [64] |

Z. Chen, S. Li, Q. Mo, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 108196. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108196 |

| [65] |

K. Zhang, G. Lu, Z. Xi, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 2207-2211. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.12.021 |

| [66] |

W. Zhong, R. Sa, L. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 7615-7621. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b02997 |

| [67] |

Z. Gu, Z. Shan, Y. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 35 (2024) 108356. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108356 |

| [68] |

J. Wang, Y. Shi, Y. Wang, et al., ACS Energy Lett. 7 (2022) 2043-2059. DOI:10.1021/acsenergylett.2c00752 |

| [69] |

V. Srivastava, P.K. Singh, S. Tivari, et al., Org. Chem. Front. 9 (2022) 1485-1507. DOI:10.1039/D1QO01602D |

| [70] |

D.A. Dirocco, K. Dykstra, S. Krska, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 4802-4806. DOI:10.1002/anie.201402023 |

| [71] |

G.Z. Wang, D.G. Liu, M.T. Liu, et al., Green Chem. 23 (2021) 5082-5087. DOI:10.1039/D1GC01210J |

| [72] |

Z. Wang, H. Hojo, H. Einaga, Chem. Eng. J. 427 (2022) 131369. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.131369 |

| [73] |

M.A. Miranda, M.L. Marin, Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 6 (2017) 139-149. DOI:10.1016/j.cogsc.2017.05.001 |

| [74] |

F. Strieth-Kalthoff, M.J. James, M. Teders, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (2018) 7190-7202. DOI:10.1039/C8CS00054A |

| [75] |

Y. Zhang, K. Ren, L. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 33-60. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.06.013 |

| [76] |

Q. Jin, T. Liu, D. Chen, et al., Front. Pharmacol. 14 (2023) 1097206. DOI:10.3389/fphar.2023.1097206 |

| [77] |

L. Jin, H. Hua, Y. Ji, et al., Biomolecules and Biomedicine 23 (2023) 376-391. |

| [78] |

S. Triemer, K. Gilmore, G.T. Vu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 5525-5528. DOI:10.1002/anie.201801424 |

| [79] |

L. Feng, Y. Wang, S. Yuan, et al., ACS Catal. 9 (2019) 5111-5118. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b04960 |

| [80] |

S. Fu, S. Yao, S. Guo, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 20792-20801. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c08908 |

| [81] |

H. Ling, J.T. Luoma, D. Hilleman, Cardiol. Res. 4 (2013) 47-55. |

| [82] |

M. Benej, X.Q. Hong, S. Vibhute, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115 (2018) 10756-10761. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1808945115 |

| [83] |

J.K. Jin, K. Wu, X.Y. Liu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 21340-21349. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c10008 |

| [84] |

A. Kassa, A. Abebe, G. Tamiru, et al., ChemistrySelect 7 (2022) e202103458. DOI:10.1002/slct.202103458 |

| [85] |

T. Zhang, C. Si, K. Guo, et al., Inorg. Chem. 61 (2022) 20657-20665. DOI:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c03627 |

| [86] |

T. Gnecchi-Ruscone, D.R. Pecorella, JAMA Surg. 154 (2019) 565. |

| [87] |

F. Kleemiss, A. Justies, D. Duvinage, et al., J. Med. Chem. 63 (2020) 12614-12622. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00813 |

| [88] |

C. Xu, Y. Pan, G. Wan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 19110-19117. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b09954 |

| [89] |

A. Mohammed, M.A. Ibrahim, N. Tajuddeen, et al., Phytother. Res. 34 (2020) 486-504. DOI:10.1002/ptr.6544 |

| [90] |

L. Palumbo, S. Fiorito, F. Epifano, et al., Phytochem. Anal. 34 (2023) 153-162. DOI:10.1002/pca.3203 |

| [91] |

G.Y. Qiao, S. Yuan, J. Pang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 18224-18228. DOI:10.1002/anie.202007781 |

| [92] |

H. Zheng, Y. Hou, S. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 5013-5022. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.01.048 |

| [93] |

K. Geng, T. He, R. Liu, et al., Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 8814-8933. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00550 |

| [94] |

X. Li, J. Zhang, Y. Huo, et al., Appl. Catal. B 280 (2021) 119452. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119452 |

| [95] |

Z. Wang, C.Y. Guo, C. Yang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 5617-5622. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b00681 |

| [96] |

Z. Almansaf, J. Hu, F. Zanca, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13 (2021) 6349-6358. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c21370 |

| [97] |

Y.H. Chuang, S. Chen, C.J. Chinn, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (2017) 13859-13868. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.7b03570 |

| [98] |

D.B. Miklos, C. Remy, M. Jekel, et al., Water Res. 139 (2018) 118-131. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2018.03.042 |

| [99] |

P. Sun, C. Tyree, C.H. Huang, Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 (2016) 4448-4458. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.5b06097 |

| [100] |

M. Kou, Y. Wang, Y. Xu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202200413. DOI:10.1002/anie.202200413 |

| [101] |

J. Yan, Y. Xu, F. Zhuang, et al., Mol. Divers. 20 (2016) 567-573. DOI:10.1007/s11030-016-9657-z |

| [102] |

H. Liu, X. Yan, W. Chen, et al., Sci. China Chem. 64 (2021) 827-833. DOI:10.1007/s11426-020-9931-4 |

| [103] |

M. Ansari, M. Montazeri, A. Daryani, et al., Mol. Divers. 24 (2020) 1223-1234. DOI:10.1007/s11030-019-09986-9 |

| [104] |

B.C. Swain, S.K. Mukherjee, J. Rout, et al., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 412 (2020) 2565-2577. DOI:10.1007/s00216-020-02483-1 |

| [105] |

H. Chen, W. Liu, A. Laemont, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 10820-10827. DOI:10.1002/anie.202101036 |

| [106] |

M. Muller, S. Koser, O. Tverskoy, et al., Chem. 25 (2019) 6082-6086. DOI:10.1002/chem.201900462 |

| [107] |

F. Turkan, Z. Huyut, P. Taslimi, et al., J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 32 (2018) e22041. DOI:10.1002/jbt.22041 |

| [108] |

S. Li, L. Li, Y. Li, et al., ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 8717-8726. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c01242 |

| [109] |

T.R. Cook, P.J. Stang, Chem. Rev. 115 (2015) 7001-7045. DOI:10.1021/cr5005666 |

| [110] |

Y. Fang, X. Lian, Y. Huang, et al., Small 14 (2018) e1802709. DOI:10.1002/smll.201802709 |

| [111] |

F.J. Rizzuto, L.K.S. von Krbek, J.R. Nitschke, Nat. Rev. Chem. 3 (2019) 204-222. DOI:10.1038/s41570-019-0085-3 |

| [112] |

B. Huang, L. Mao, X. Shi, et al., Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 13648-13663. DOI:10.1039/D1SC01618K |

| [113] |

Y. Jin, Q. Zhang, Y. Zhang, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (2020) 5561-5600. DOI:10.1039/C9CS00917E |

| [114] |

Y. Hao, F. Zhang, S. Mo, et al., Front. Mol. Biosci. 8 (2021) 700712. DOI:10.3389/fmolb.2021.700712 |

| [115] |

W. Cullen, H. Takezawa, M. Fujita, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 9171-9173. DOI:10.1002/anie.201904752 |

| [116] |

T. Noguchi, S. Isogai, T. Terada, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144 (2022) 5435-5440. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c13074 |

| [117] |

R. Rogers, P.J. Krause, A.M. Norris, et al., Clin. Infect. Dis. 76 (2023) 741-744. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciac473 |

| [118] |

J. Guo, Y.W. Xu, K. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 3852-3856. DOI:10.1002/anie.201611875 |

| [119] |

D.J. Hwang, Y. He, S. Ponnusamy, et al., J. Med. Chem. 66 (2023) 3372-3392. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01858 |

| [120] |

Q. Pang, W.F. Zuo, Y. Zhang, et al., Chem. Rec. 23 (2023) e202200289. DOI:10.1002/tcr.202200289 |

| [121] |

Z. Wei, X. Jing, Y. Yang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202214577. DOI:10.1002/anie.202214577 |

| [122] |

A. Siwach, P.K. Verma, BMC Chem. 15 (2021) 12. DOI:10.1186/s13065-020-00730-1 |

| [123] |

S. Tahlan, S. Kumar, B. Narasimhan, BMC Chem. 13 (2019) 101. DOI:10.1186/s13065-019-0625-4 |

| [124] |

H.M. Diab, D.M. Mohamed, A.F. Darweesh, et al., J. Heterocycl. Chem. 60 (2023) 754-767. DOI:10.1002/jhet.4624 |

| [125] |

X. Han, C. Guo, C. Xu, et al., ACS Nano 17 (2023) 3723-3736. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.2c10856 |

| [126] |

Y. Han, K. Xing, J. Zhang, et al., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 209 (2021) 112885. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112885 |

| [127] |

K. Abe, K. Irie, H. Nakanishi, et al., Nature 556 (2018) 214-218. DOI:10.1038/s41586-018-0003-8 |

| [128] |

L.X. Cai, S.C. Li, D.N. Yan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 4869-4876. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b00394 |

| [129] |

D.N. Yan, L.X. Cai, P.M. Cheng, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 16087-16094. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c06390 |

| [130] |

M.R. van der Kolk, M. Janssen, F. Rutjes, et al., ChemMedChem 17 (2022) e202200020. DOI:10.1002/cmdc.202200020 |

| [131] |

J.S. Wang, K. Wu, C. Yin, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 4675. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-18487-5 |

| [132] |

T. Wang, B.B. Tian, B. Han, et al., Energy Environ. Mater. 5 (2022) 711-730. DOI:10.1002/eem2.12229 |

| [133] |

Z.H. Syed, F. Sha, X. Zhang, et al., ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 11556-11566. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c03056 |

| [134] |

Z. Zhang, J. Jia, Y. Zhi, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 51 (2022) 2444-2490. DOI:10.1039/D1CS00808K |

| [135] |

A. Bavykina, N. Kolobov, I.S. Khan, et al., Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 8468-8535. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00685 |

| [136] |

Y. Bai, L. Wilbraham, B.J. Slater, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 9063-9071. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b03591 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35