b Department of In Vitro Diagnostic Reagent, National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, Beijing 100050, China;

c State Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Plant Resources in West China, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650201, China

Polyketides play an important role in natural medicinal chemistry due to their complex structures and a wide variety of biological activities such as lovastatin, strobilurin, and fumagillin [1–3]. Aromatic polyketides are a large subclass of natural products that have attracted a great deal of attention not only because of their diverse structures and fascinating bioactivities but also their biosynthetic pathways [4–7]. Duclauxin derivatives, which are mainly reported from Penicillium and Talaromyces species, are dimeric oxaphenalenones consisting of at least one unit of the dihydrocoumarin benzo[de]isochromen-1(3H)-one [8,9]. The first duclauxin was isolated from the culture of the fungus Talaromyces duclauxii in 1965 [10], which is a well-known antitumor agent that inhibits ATP synthesis in mitochondria [11]. Detailed literature investigation revealed that there are about 36 naturally occurring duclauxins to date, which displayed a diverse range of biological activities, such as cytotoxic, antimicrobial, antiviral, kinase inhibitory, and phytotoxic activities [12]. Furthermore, in 2018, Tang and co-workers characterized the cascade of redox transformations in the biosynthetic pathway of duclauxin from Talaromyces stipitatus [13]. The fungus T. stipitatus is a rich source of secondary metabolites, including polyketides, terpenoids, steroids, alkaloids, and so on [14–17], of which duclauxins are the main chemical constituents with 16 examples [12].

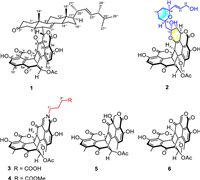

In our previous report, four fusicoccane diterpenoids with a 5/8/6 carbon skeleton as well as five steroids were obtained from T. stipitatus [18,19]. During our continuous investigation on this fungus, two novel duclauxin hybrids (1 and 2) with two types of unique structural frameworks, along with three new (3−5) and a known analogue (6) were isolated (Fig. 1). Talaroclauxin A (1) features an unprecedented dodecacyclic ring system that is fused by ergosterol and duclauxin via a [4 + 2] cycloaddition. Talaroclauxin B (2) exhibits an unusual 6/6/6/5/6/6/6/6 ring system derived from the polymerization between a duclauxin and an additional polyketide. Herein, we report the isolation, structural elucidation, biological evaluation, and plausible biogenetic pathways of these duclauxin hybrids.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. The structures of compounds 1−6. | |

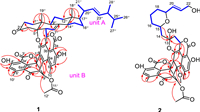

Talaroclauxin A (1) was obtained as a white powder. Its molecular formula of C56H60O11 was determined based on a (+)-HRESIMS peak at m/z 931.4038 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C56H60O11Na, 931.4033) and required 27 degrees of unsaturation. The 1H and 13C NMR data (Table S1 in Supporting information) of 1 displayed characteristic resonances of an ergostane-type steroid [δH 5.21 (1H, dd, J = 15.3, 7.5 Hz), 5.13 (1H, dd, J = 15.3, 8.0 Hz), 1.37 (3H, s), 1.03 (3H, d, J = 6.6 Hz), 0.89 (3H, d, J = 6.8 Hz), 0.81 (3H, d, J = 6.6 Hz), 0.79 (3H, d, J = 6.6 Hz), and 0.61 (3H, s)]. The key 1H–1H COSY correlations (Fig. 2) of 1 indicated the presence of four independent spin systems [H2-1″/H2-2″, H-6″/H-7″, H-9″/H2-11″/H2-12″, and H-14″/H2-15″/H2-16″/H-17″/H-20″(Me-21″)/H-22″/H-23″/H-24″(Me-28″)/H-25″/Me-26″(Me-27″)]. Moreover, the HMBC correlations from Me-18″ to C-12″, C-13″, C-14″, and C-17″, from Me-19″ to C-1″, C-5″, C-9″, and C-10″, from H2-4″ to C-2″, C-3″, C-5″, C-6″, and C-10″, and from H-7″ to C-8″, C-9″, and C-14″ constructed the planar structure of the ergosterol moiety.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Key 1H−1H COSY, and HMBC correlations of 1 and 2. | |

The remaining signals were assigned to three methyl singlets (δH 3.00, 2.59 and 2.02), an oxygenated methylene (δH 4.87 and 4.78, both d, J = 12.5 Hz), five methines, including two olefinic ones (δH 6.94 and 6.86, both s), and 19 nonprotonated carbons, including one ketocarbonyl (δC 190.4), three ester carbonyls (δC 170.5, 170.3, 167.2), one sp3 quaternary carbon (δC 48.4), and 14 olefinic carbons. The NMR-based structural analysis of these remaining signals indicated a condensed polyaromatic system which was challenging due to the low H/C ratio. Based on literature investigations, the aforementioned NMR data indicated that the unit should be a duclauxin. The main HMBC correlations from Me-10(10′) to C-5(5′), C-6(6′) and C-6a(6a′), from H-1(1′) to C-3b(3b′), C-9(9′) and C-9a(9a′), from OH-4(4′) to C-3a(3a′), C-4(4′) and C-5(5′), from H-5(5′) to C-3a(3a′), C-4(4′), C-6(6′) and C-6a(6a′), from H-8′ to C-7, C-7′ and C-9a′ confirmed the planimetric map of unit B which was similar to bacillisporin A [20]. The connectivity of the two units through the C-1−C-6″ and C-9−O−C-5″, which was deduced by the 1H−1H COSY correlation of H-1/H-6″ and the remaining one degree of unsaturation, as well as the highly deshielded 13C chemical shift of C-5″ (δC 88.3) compared with (22E, 24R)-ergosta-7,9(11), 22-trien-3β, 5β, 6β-triol (δC 74.2) [21].

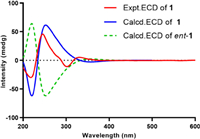

The relative configuration of the core steroidal part was assumed to be the same as that of typical ergosterol analogues and confirmed by the corresponding NOESY correlations (Fig. S1 in Supporting information) of H3-19″/H3-18″, H3-19″/H-6″, H-9″/H-14″, H-14″/H-17″, H3-18″/H3-21″, and H-20″/H-16″. The key NOESY correlation of H-1 and H-4″ unraveled the orientation of H-1. As almost no coupling was observed between H-8′ and H-9′, suggesting a torsion angle of ca. 90° between these two protons. In addition, NOESY correlations of H-8′/H-9′, H-8′/H3-10 as well as H-9′/H-1′α are in agreement with the configuration of bacillisporin A [20]. Furthermore, the key NOESY correlations of H-1′ and H-9″ established the whole relative configuration of compound 1. To further confirm the relative configuration of 1, the theoretical 13C NMR calculation of 1 (1S*, 1′S*, 8′R*, 9′S*, 5″S*, 6″S*, 9″R*, 10″R*, 13″R*, 14″R*, 17″R*, 21″R*, 24″R*) was performed, and the calculated 13C NMR of 1 matched well with experimental data (Fig. S2 in Supporting information). Finally, the absolute configuration of 1 was determined as 1S, 1′S, 8′R, 9′S, 5″S, 6″S, 9″R, 10″R, 13″R, 14″R, 17″R, 21″R, 24″R by ECD calculations (Fig. 3).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Comparison of the experimental and calculated ECD spectra of 1. | |

Talaroclauxin B (2) was isolated as a colorless crystal and gave a molecular formula of C40H40O14 based on its HRESIMS ion peak at m/z 767.2313 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C40H40O14Na, 767.2316), indicating 21 degrees of unsaturation. The 1H and 13C NMR data (Table S2 in Supporting information) of 2 showed similarity to those of 1, and the difference was the appearance of an additional nine-carbon alkyl chain and absence of ergosterol signals in 2, which was supported by the 1H−1H COSY correlations (Fig. 2) of H2-14/H-15/H2-16/H2-17/H2-18/H-19/H-20/H-21/H2-22. Furthermore, the HMBC correlations from H2-14 and H-15 to C-13 suggested that the alkyl chain was located at C-13. Finally, based on the chemical shifts of C-15 (δH 4.32; δC 74.8) and C-19 (δH 4.11; δC 77.4) along with the degrees of unsaturation, a pyran ring was assigned via an oxygen bridge between C-15 and C-19.

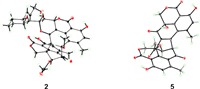

The NOESY correlations of H-8′/H-9′, H-8′/H3-10, H-9′/H-1′α, H-8/H-1′β, and H-8/H3-11 suggested identical configurations in the duclauxin moiety [8]. Moreover, the strong NOESY correlation between H-15 and H-19 indicated they were cofacial. However, it is a challenge to uncover the whole relative configuration of 2 by interpreting the NMR data alone. With a varied range of attempts, a single crystal of 2 suitable for X-ray diffraction was obtained by slowly crystallizing in MeOH/CH2Cl2 (1:1) at room temperature, which confirmed both planar structure and absolute configuration of 2 (Fig. 4).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. X-ray structures of 2 and 5. | |

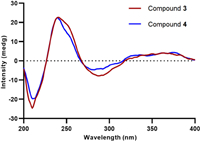

Talaroclauxin C (3) gave an ion [M + Na]+ at m/z 654.1573, consisting with the molecular formula of C33H29NO12 and indicating 20 degrees of unsaturation. Detailed analyses of 1D and 2D NMR data showed that compound 3 is similar to bacillisporin H [16], except for the presence of a butanoic acid chain, which was disclosed by the 1H−1H COSY correlations (Fig. S5 in Supporting information) of H2-1″/H2-2″/H2-3″ and the HMBC correlations from H2-2″ and H2-3″ to C-4″. Additionally, the HMBC correlation from H-1 to C-1″ supported that the chain was located at the N atom. Talaroclauxin D (4) was isolated as a faint yellow powder and gave an HRESIMS ion peak corresponding to a molecular formula of C34H31NO12, which was 14 mass units more than 3. The only difference was that the carboxyl group in 3 was replaced by a methoxycarbonyl in 4, which was confirmed by the presence of an additional methoxyl (δH 3.73, s; δC 52.0) and the HMBC correlation from Me-5″ to C-4″. The NOESY correlations of H-8′/H-9′, H-8′/H3-10, H-9′/H-1′α, H-8/H-1′β, and H-8/H3-11 were similar to those of 2, suggesting the same relative configuration for 3 and 4. The absolute configurations of 3 and 4 were established as 7S, 8S, 8′S, 9′S, 9a′R based on their experimental ECD spectra (Fig. 5) showing almost the same Cotton effects as these of duclauxin [22].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Experimental ECD spectra of compounds 3 and 4. | |

Talaroclauxin E (5) was isolated as a colorless crystal with the molecular formula of C28H20O11 (19 degrees of unsaturation), as deduced from the molecular peak at m/z 555.0913 [M + Na]+ in the HRESIMS. Interpretation of the 1H and 13C NMR data (Tables S3 and S4 in Supporting information) revealed that 5 possessed the same planar structure as bacillisporin E [20], except for the slight differences in H2-1 (δH 4.89 and 4.42 in 5; δH 4.90 and 4.82 in bacillisporin E), indicating that 5 is likely the C-9a epimer of bacillisporin E. Finally, a high-quality crystal of 5 was obtained from a solution of MeOH at 4 ℃, which confirmed the above analyses based on the flack parameter of 0.024(5) (Fig. 4).

The possible biosynthetic pathways of 1−6 are proposed as shown in Scheme 1 and Scheme S1 (Supporting information). Firstly, the diradical-coupling of two oxaphenalenone monomers produced a heptacyclic oligophenalenone dimer, which could be converted to compounds 5 and 6. On the one hand, after a dehydration reaction of 5, intermediate Ⅰ with an additional double bond Δ1,9a was generated. Then, the α,β-unsaturated ketone in Ⅰ and the olefinic functionality at C-5 and C-6 in the (22E)-ergosta-5,7,22-trien-3-one could undergo a [4 + 2] cycloaddition reaction to obtain 1. On the other hand, compound 2 could be produced via two possible pathways (A and B) from 6. In pathway A, the [4 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of 6 and b (enoic acid) was the key step, which was followed by a decarboxylation. In pathway B, a Michael addition reaction was proposed as the key step between compound 6 and a (the keto form of b) led to the key intermediate Ⅲ, and the followed decarboxylation and intramolecular nucleophilic addition reactions led to compound 2. In addition, 6 might undergo acylation with a glutamic acid, followed by the nucleophilic addition to form intermediate V, which was then transformed into 3 by decarboxylation and into 4 by an additional methylation (Scheme S1).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Hypothetical biosynthetic pathways of compounds 1 and 2. | |

After no-toxicity confirmation (Fig. 6A), the cytoprotective and anti-neuroinflammatory activities of 1−6 were evaluated. Encouragingly, compound 5 showed potential neuroprotection effect against 20 mmol/L glutamate-induced oxidative injury in SH-SY5Y cells, which was better than the H2O2 oxidative stress model (Figs. 6B and C). Treated with 5 and 10 µmol/L of 5 could significantly reduce the glutamate-induced cell death from 39.6% to 15.2% and 9.5%, respectively. The additional Annexin V-FITC/PI double dying assay showed that 5 can reduce the large proportion of apoptotic cells in a dose-depended manner which was consistent with the CCK8 assay (Figs. 6D and E). Furthermore, the lower ROS production verified that 5 dose-dependently resisted the oxidative stress (Figs. 6F and G). These results suggested that 5 inhibited ROS production in SH-SY5Y cells and thereby inhibited glutamate-induced oxidative injury. In addition, 5 simultaneously showed significant protective effects on LPS-induced BV-2 cell injury and attenuate NO production, combining the decreasing transcriptional levels of several inflammatory associated genes, including AMPK, TNF-α, PPARα, IL-18, and TLR4 (Fig. S8 in Supporting information). All results demonstrate 5 may be a potential candidate for regulating oxidative injury and neuroinflammatory response in the brain for nervous system disease.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. The cytoprotective activity of 5 against glutamate/H2O2-induced oxidative injury in SH-SY5Y cells. (A) Cytotoxicity assay of 1−6 in SH-SY5Y cells. (B, C) The cytoprotective activity of 5 in glutamate (20 mmol/L) or H2O2 (500 µmol/L) induced cell injury. (D, E) Flow cytometry was applied to determine the apoptotic ratio after Annexin V-FITC/PI staining. (F, G) The intracellular ROS production was measured using DCFH-DA method. All results were calculated as the mean ± SD. ###P < 0.001 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. the glutamate or H2O2-treated group. | |

In conclusion, two novel duclauxin hybrids together with three new and one known analogues were isolated from Talaromyces stipitatus. Compound 1 represents the first example of duclauxin-ergosterol hybrid possessing an unprecedented 6/6/6/5/6/6/6/6/6/6/6/5-fused dodecacyclic scaffold, and compound 2 is a new member of the rare duclauxin-polyketide hybrid. Moreover, compound 5 exhibited neuroprotective effects in SH-SY5Y cells, indicating that 5 might be a promising leading scaffold for regulating oxidative injury and neuroinflammatory response in the brain for nervous system disease.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was financially supported by the Program for Changjiang Scholars of Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (No. T2016088), the National Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 81725021), the National Natural Science Foundation for Excellent Young Scholars (No. 81922065), Innovative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81721005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82173706), the Science and Technology Major Project of Hubei Province (No. 2021ACA012), the Research and Development Program of Hubei Province (No. 2020BCA058), the Academic Frontier Youth Team of HUST (No. 2017QYTD19), and the Integrated Innovative Team for Major Human Diseases Program of Tongji Medical College (HUST). The authors thank the Analytical and Testing Center at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology for assistance in the acquisition of the NMR, ECD, and UV spectra. The computation is completed in the HPC Platform of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108193.

| [1] |

S. Lin, J. Huang, H. Zeng, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4587-4594. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.064 |

| [2] |

Y. Du, Z. Chen, H. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 981-984. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.01.034 |

| [3] |

C. Hertweck, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48 (2009) 4688-4716. DOI:10.1002/anie.200806121 |

| [4] |

H. Zhou, Y. Li, Y. Tang, Nat. Prod. Rep. 27 (2010) 839-868. DOI:10.1039/b911518h |

| [5] |

S. Chen, C. Zhang, L. Zhang, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202202286. DOI:10.1002/anie.202202286 |

| [6] |

Q. Shen, G. Dai, A. Li, et al., J. Nat. Prod. 84 (2021) 2875-2884. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00617 |

| [7] |

Z.Y. Ji, Q.Y. Nie, Y. Yin, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 18046-18054. DOI:10.1002/anie.201910882 |

| [8] |

N.K. Chaudhary, A. Crombie, D. Vuong, et al., J. Nat. Prod. 83 (2020) 1051-1060. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01066 |

| [9] |

P. Cao, J. Yang, C.P. Miao, et al., Org. Lett. 17 (2015) 1146-1149. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00081 |

| [10] |

S. Shibata, Y. Ogihara, N. Tokutake, et al., Tetrahedron Lett. 6 (1965) 1287-1288. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77197-8 |

| [11] |

L. Kovac, E. Bohmerova, J. Fuska, J. Antibiot. 31 (1978) 616-620. DOI:10.7164/antibiotics.31.616 |

| [12] |

H. Shahid, T. Cai, Y.Y. Wang, et al., Front. Microbiol. 12 (2021) 766440. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2021.766440 |

| [13] |

S.S. Gao, T. Zhang, M. Garcia-Borras, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 6991-6997. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b03705 |

| [14] |

Y. Zang, G. Genta-Jouve, T.A. Sun, et al., Phytochemistry 119 (2015) 70-75. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.09.002 |

| [15] |

Y. Zang, G. Genta-Jouve, P. Retailleau, et al., Org. Biomol. Chem. 14 (2016) 2691-2697. DOI:10.1039/C5OB02657A |

| [16] |

Y. Zang, G. Genta-Jouve, A.E. Escargueil, et al., J. Nat. Prod. 79 (2016) 2991-2996. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00458 |

| [17] |

J. Noinart, S. Buttachon, T. Dethoup, et al., Mar. Drugs 15 (2017) 139-150. DOI:10.3390/md15050139 |

| [18] |

M. Zhang, S. Yan, Y. Liang, et al., Org. Chem. Front. 7 (2020) 3486-3492. DOI:10.1039/d0qo00960a |

| [19] |

M. Zhang, Y. Deng, F. Liu, et al., Phytochemistry 189 (2021) 112816. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112816 |

| [20] |

T. Dethoup, L. Manoch, A. Kijjoa, et al., Planta Med. 72 (2006) 957-960. DOI:10.1055/s-2006-947188 |

| [21] |

Q. Shi, Y. Huang, H. Su, et al., Phytochemistry 168 (2019) 112109. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112109 |

| [22] |

M. Wang, L. Yang, L. Feng, et al., Mar. Drugs 17 (2019) 516-525. DOI:10.3390/md17090516 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35