b College of Chemistry, and Institute of Green Catalysis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, China;

c College of Chemistry, Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing 401331, China

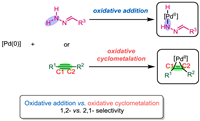

Alkynes are key building blocks in organic synthesis because they are widely used to obtain valuable compounds, including alkanes, alkenes, ketones, and cyclic hydrocarbons, which are prevalent in pharmaceuticals, natural products, optical materials, and pesticides [1–10]. Owing to the highly reactive nature of C≡C bonds, alkynes can easily react with transition metal catalysts (e.g., Pd, Rh, Cu, Ag, and Au, among others), where the metals often serve as π-acids [11–22,3,23]. Numerous important synthetic methods relating to alkyne transformations (e.g., Fujiwara Reaction, Pauson-Khand Reaction, and Larock Reaction) have been developed [24–28]. Over the past few decades, the metal-catalyzed transformation of alkynes to multi-substituted alkenes has emerged as a direct and efficient strategy for producing multi-functionalized alkenes [29–35]. Targeted multi-substituted alkenes represent one of the most useful building blocks for organic synthesis, owing to their abundance and versatile reactivity [36–41]. Scheme 1 summarizes the established reaction pathways for converting internal alkynes to multi-substituted alkenes. When an M–H or M–Nu intermediate is generated, insertion of the alkyne C≡C bond into the M–H/M–Nu bond could yield vinyl-metal intermediates, where the intermediates, where the two substituents (R1 and R2) from the alkyne typically adopt cis-positions in the product alkene (Scheme 1, Mode A) [42–47]. Alternatively, alkynes could act as π-ligands coordinating to the transition metal centers; in this case, the C≡C bond would be activated, leading to intermolecular nucleometallation, which generates vinyl-metal intermediates. The R1 and R2 groups following this reaction would likely adopt trans-positions in the product (Scheme 1, Mode B) [48–52]. Alkyne transformation reactions catalyzed by Ti, Zr, Ta, and other early transition metals typically involve an oxidative cyclometallation of the C≡C bond with the metal center to form three- or five-membered ring metallacycle intermediates [53–60]. However, although there are limited reports describing oxidative cyclopalladation via five-membered palladacycle intermediates [61–65], even fewer examples involving three-membered palladacycles have been reported [66]. Thus, herein we propose a novel alkyne activation model, whereby oxidative cyclopalladation of a C≡C bond yields an active three-membered palladacycle intermediate. Subsequent electrophilic attack or hydrogen atom transfer can generate multi-substituted alkenes (Scheme 1, Mode C).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Reaction modes for the conversion of alkynes to multi-substituted alkenes. | |

To better understand this reaction, we focused on the Pd-catalyzed hydroalkylation of alkynes recently reported by Li and co-workers to validate our proposal (Scheme 2) [67]. In this work, hydrazones were selected as the hydroalkylation partners, and trisubstituted alkenes were obtained in moderate-to-high yield, with high regioselectivity. The present study employed density functional theory (DFT) to investigate the potential mechanisms of the Pd-catalyzed hydroakylation reaction, while focusing on the mode of activation and the transformation of alkynes.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Pd-catalyzed hydroalkylation of alkynes with hydrazones. | |

All of the DFT calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16 [68] series of programs in the solution phase with the solvation-model density (SMD) [69–71] model (solvent = 1,4-dioxane). The B3LYP-D3 functional [72–75] was applied with the standard def2-SVP [76–78] basis set for all atoms to conduct geometry optimizations in 1,4-dioxane. Harmonic vibrational frequency calculations were performed for all stationary points to (ⅰ) determine whether they corresponded to local minima or transition state structures and (ⅱ) derive thermochemical corrections for the enthalpies and free energies. The M06 [79–82] functional proposed by Truhlar and co-workers was used with the def2-TZVP [76–78] basis set for all atoms to calculate the single-point energies in 1,4-dioxane, thus providing accurate energy information. The solvent effects were considered based on single-point calculations of the solution-phase stationary points simulated with the SMD continuum model. The Gibbs free energies (ΔGM06(1,4-dioxane)) reported in this paper were obtained using Eq. 1,

|

(1) |

where ΔG(correction) is the thermochemical correction for the Gibbs free energy calculated at the B3LYP-D3/def2-SVP level in the solution phase (solvent = 1,4-dioxane), and ΔEM06(1,4-dioxane) is the single-point energy calculated at the M06/def2-TZVP level in 1,4-dioxane relative to stationary points in the 1,4-dioxane solvent. The ΔGM06(1,4-dioxane) values are used to discuss the energies. The Mayer bond order [83,84], interaction region indicator (IRI) [85], Laplacian of the electron density [86–88], and localized orbital bonding analysis (LOBA) [89] were calculated at the B3LYP-D3/def2-SVP level in 1,4-dioxane. The electrostatic potential was also computed using the highly effective algorithm of the Multiwfn program [90].

Hydrazones served as the hydroalkylation partners in the present work. Existing reports generally propose that the catalytic cycle begins with hydrazone activation by Pd(0). Therefore, there is a competition between acetylene activation and hydrazones activation in the catalytic cycle. As shown in Scheme 3, the oxidative addition of the hydrazone N–H moiety to the Pd(0) center could generate a Pd(Ⅱ)-hydrazinide species, which facilitates subsequent denitrogenation and C–C bond formation. Alternatively, acetylene activation by Pd(0) via oxidative cyclopalladation could generate a metallacyclopropene species, which could also convert to the desired product. Therefore, there is a competition between the hydrazone and acetylene activation pathways. Two catalytic cycles involving these proposes are illustrated in Fig. 1. All pathways begin with the Pd(0) species Ⅰ, and in the first step, the hydrazone coordinates to the Pd center to yield intermediate Ⅲ. In Path A (proposed by Li et al.), hydrazine N–H oxidative addition occurs to yield Pd(Ⅱ)-hydrazinide Ⅴ. Subsequent alkyne insertion affords the six-membered palladacycle Ⅵ, which can undergo base-assisted denitrogenation to form the four-membered palladacycle intermediate Ⅶ. Protonation of Ⅶ generates the alkenyl Pd(Ⅱ) intermediate Ⅷ. Finally, reductive elimination releases the desired Z-alkene P, and ligand exchange with phosphine oxide regenerates the Pd(0) species Ⅰ. In Path B, oxidative cyclometallation of alkyne Ⅳ with the Pd center generates palladacyclopropene intermediate Ⅸ. Subsequent base-assisted isomerization via proton transfer forms hydrazone-coordinated Pd(Ⅱ) intermediate Ⅹ, which then undergoes denitrogenation to generate an alkyl-bonded Pd(Ⅱ) species Ⅺ. Protonation of Ⅺ opens the palladacyclopropene ring to afford the vinyl Pd(Ⅱ) intermediate Ⅻ, and finally, reductive elimination releases the desired Z-alkene P and regenerates the Pd(0) catalyst.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. Competitive Pd-catalyzed reaction pathways: acetylene activation and hydrazone activation. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Potential reaction pathways for Pd-catalyzed hydroalkylation of alkynes with hydrazones. | |

We first considered Path A, which was proposed following the experimental studies. As shown in Fig. 2, Pd(PCy3)(OPCy3) 1 was chosen as the relative zero point for the free energy profiles (further details in Supporting information). In Path A, the coordination of hydrazone 2 to the Pd(0) species generates intermediate 3 through an endergonic process (+6.7 kcal/mol). Oxidative addition of the N–H bond to the Pd center then generates Pd(Ⅱ)-hydrazinide intermediate 5 via transition state ts-4, which endergonic by an additional 12.3 kcal/mol; the energy barrier for this step is 20.3 kcal/mol. Subsequent ligand exchange with 1,2-diphenylethyne 6 forms intermediate 7 and releases a phosphine oxide species in another endergonic process (+1.8 kcal/mol). Conjugative insertion of the alkyne via transition state ts-8 has an energy barrier of 22.7 kcal/mol, and the generation of vinyl Pd intermediate 9 is endergonic by 1.3 kcal/mol. Geometric optimization of transition state ts-8 revealed Pd−C3 and C1−C2 bond lengths of 2.33 and 2.34 Å, respectively. Deprotonation of intermediate 9 by the base (1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec–7-ene; DBU) via transition state ts-10 leads to synergistic denitrogenation. The calculated free energy barrier is 9.0 kcal/mol, and this step is associated with a free energy release of 33.6 kcal/mol. In ts-10, the Pd−N1, C1−N2, H − N1, and H − N3 bond distances are 2.06, 1.53, 1.50, and 1.14 Å, respectively, which verifies the synergistic process. Subsequent protonation of 11 occurs via transition state ts-12, overcoming an energy barrier of 20.7 kcal/mol to afford vinyl Pd-hydride intermediate 13, which releases 15.0 kcal/mol of free energy. Rapid reductive elimination of 13 yields the final Z-alkene 15 via transition state ts-14, with concomitant regeneration of the active Pd(0) species 1; this step is exergonic by 32.8 kcal/mol. The calculated overall activation free energy for Path A is as high as 43.5 kcal/mol, indicating that this reaction pathway is kinetically unfavorable.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Free energy profile and selected transition state (ts) and intermediate structures along Path A for Pd-catalyzed hydroalkylation of alkynes with hydrazones. Energies are reported in kcal/mol and represent the relative free energies calculated with the DFT/M06 method in 1,4-dioxane; bond distances are reported in angstroms. | |

Next, an alternative pathway was analyzed based on our proposal, where the Pd(Ⅱ) species acts as a good Lewis acid during hydrazine activation. As shown in Fig. 3 (Path B), hydrazone 2 coordinates with Pd to form intermediate 3, and then, 1,2-diphenylethyne 6 performs ligand exchange with phosphine oxide in 3 to produce intermediate 16. Oxidative cyclization of the alkyne π bond to the Pd center in intermediate 16 forms the three-membered pallada(Ⅱ)cycle intermediate 17. This step is associated with a free energy absorption of 1.3 kcal/mol, and the geometry of the Pd changes to square planar. Moreover, in intermediate 16, the Pd−C1, Pd−C2, and C1−C2 bond lengths are 3.51, 3.42, and 1.22 Å, respectively; however, those bond lengths in intermediate 17 are 2.07, 2.06, and 1.29 Å, respectively. Following base-assisted deprotonation and re-protonation via transition states ts-18 and ts-20, respectively, the proton on the hydrazonic N-atom could transfer to the benzylic C-atom of intermediate 17; thereby achieving isomerization of the coordinated hydrazone to alkylenehydrazine in pallada(Ⅱ)cycle 21. The calculated energy barrier of proton transfer is 22.0 kcal/mol. Subsequent base-assisted denitrogenation via transition state ts-22 generates benzylic pallada(Ⅱ)cycle 23 with an energy barrier of 16.1 kcal/mol, and this step is exergonic by 24.4 kcal/mol. In intermediate 23, the Pd(Ⅱ) center has a lone pair of electrons in the axial direction [91,92]. There should be a weak interaction between the B-H+ and the Pd dz2 lone pair. Protonation of the carbon atom on the three-membered pallada(Ⅱ)cycle moiety via transition state ts-24 generates vinyl Pd(Ⅱ) intermediate 25 in an exergonic process (–25.9 kcal/mol). The calculated energy barrier for this step is 13.5 kcal/mol. Finally, reductive elimination via transition state ts-26 affords the Z-alkene product 15 (exergonic by 24.3 kcal/mol) and regenerates the active Pd(0) catalyst 1. The calculated overall activation free energy of Path B is only 27.4 kcal/mol, which is 16.1 kcal/mol lower than that of Path A. These results confirm that our proposed mechanism is feasible.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Free energy profile and selected transition state and intermediate structures along Path B for the Pd-catalyzed hydroalkylation of alkynes with hydrazones. The energies are reported in kcal/mol and represent the relative free energies calculated with the DFT/M06 method in 1,4-dioxane; The bond distances are reported in angstroms. | |

These theoretical calculations indicate that the oxidative cyclization step in Path B is the key process for alkyne activation, and an accompanying change in the oxidation state of the Pd center is proposed. To verify the oxidation state change during oxidative cyclization, the Laplacians of the electron density (Fig. 4a), the IRI (Fig. 4b), the Mayer bond order, and the localized orbital bonding (Fig. 4c) of intermediates 16 and 17 were analyzed. The Laplacians of the electron density on the plane defined by C1, C2, and Pd in intermediates 16 and 17 were plotted using AIM theory. In 16, the bond critical point (BCP) was identified between Pd and the C1≡C2 triple bond, whereas in 17, two BCPs were detected (between Pd–C1 and Pd–C2); therefore, two new covalent bonds were formed in intermediate 17 (between Pd–C1 and Pd–C2). The IRI analysis similarly indicated that the Pd–C1 and Pd–C2 interactions in 17 were strongly attractive (dark blue area in Fig. 4b), analogous to other covalent bonds. However, Pd–C1 and Pd–C2 were only weakly interacting (light green area in Fig. 4b) in intermediate 16, which indicated non-bonding interactions. These results support the coordination of the unsaturated C≡C bond to the Pd center in 16 and covalent bonding between Pd–C1 and Pd-C2 in 17. The bonding between C1 and C2 was also considered. As shown in Fig. 4c, the calculated Mayer bond orders of Pd–C1, Pd–C2, and C1–C2 in intermediate 16 were 0.02, 0.02 and 2.28, respectively; in contrast, those values in intermediate 17 were 0.64, 0.71, and 1.87, respectively. The results reveal that the C1–C2 bond in intermediate 16 is likely to be a triple bond, whereas the C1–C2 bond in intermediate 17 is more like a double bond. Moreover, localized orbital bonding analysis (LOBA) indicated that the oxidation states of Pd in intermediates 16 and 17 were 0 and +2, respectively. All of these analytical results strongly support the oxidative cyclization step, as well as the change in Pd oxidation state. The results revealed that the three-membered pallada(Ⅱ)cycle species plays a role of Lewis acid to assist deprotonation and re-protonation (proton transfer) of hydrazones, which is an essential precondition for denitrogenation. By this way, the coordinated hydrazone can be transformed into alkylenehydrazine, which participates in the subsequent step. Therefore, generation of pallada(Ⅱ)cycle is required at the beginning of the catalytic cycle.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) Laplacian of electron density for intermediates 16 and 17 plotted on the C1−Pd−C2 plane; (b) Three-dimensional structures and plane structures for IRI analysis of intermediates 16 and 17 on the C1−Pd−C2 plane (blue = notable attraction; green = van der Waals interaction; red = notable repulsion); (c) Bond lengths (Å), Mayer bond orders, and LOBA for intermediates 16 and 17. | |

In the experimental study, a wide range of non-symmetrical alkynes was examined, and high regioselectivities were observed (generally greater than 95:5). Based on the calculated free energy profiles of the potential reaction pathways, we concluded that the regioselectivity is governed by the protonation step when a non-symmetrical alkyne is employed as the substrate, i.e., protonation at C1 and C2 could afford the respective regioisomers. Our computational results (Fig 5a, further details in Supporting Information) indicate that the energy barrier of protonation at C2 of the benzylic pallada(Ⅱ)cycle 23′ via transition state ts-24′a is 1.6 kcal/mol lower than that at C1 via transition state ts-24′b, thus, the generation of alkene product 15′a is more favorable. The calculated regioselectivity ratio (rr) is 90:10, which is consistent with the experimentally observed regioselectivity. To further investigate the origin of this regioselectivity, the electrostatic potential intermolecular penetration diagrams of the protonated transition states ts-24′a and ts-24′b were analyzed (Fig. 5b). In transition state ts-24′a, C2 in the pallada(Ⅱ)cycle moiety has a positive surface potential, while the DBUH+ moiety has negative surface potentials, indicating that the protonation of C2 is preferential. In contrast, both the C1 and the DBUH+ moieties in transition state ts-24′b have negative surface potentials, leading to electrostatic repulsion, which is unfavorable for C1 protonation. Therefore, electrostatic potential analysis suggested that the regioselectivity of the product is controlled by the charge distribution on the pallada(Ⅱ)cycle, which governs the favorability of C2 protonation. This conclusion is consistent with the DFT computations, as well as the experimental results.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) Theoretical regioselectivities for the Pd-catalyzed hydroalkylation of non-symmetrical alkynes with hydrazones (bond distances reported in angstroms). (b) Electrostatic potential inter-molecular penetration diagrams of the protonated transition states, ts-24′a and ts-24′b. | |

In this work, a C≡C bond's oxidative cyclopalladation activation during the Pd-catalyzed hydroalkylation of alkynes was proposed and investigated by DFT calculations at the M06 level of theory. This novel pathway involves five main steps: (1) oxidative cyclopalladation with the alkyne and the Pd center to generate a palladacyclopropene; (2) base-assisted proton transfer to form alkylenehy-drazine-coordinated Pd(Ⅱ); (3) deprotonation-driven denitrogenation to form a benzylic Pd(Ⅱ) species; (4) protonation-mediated ring-opening of the palladacyclopropene to generate a vinyl Pd(Ⅱ) intermediate; and (5) reductive elimination to release the Z-alkene product. The internal alkyne plays the role of an atypical oxidant for Pd(0) oxidative cyclization. The previously proposed C≡C bond insertion for the alkyne transformation is kinetically unfavorable. The Laplacians of the electron density, IRI analysis, Mayer bond orders, and LOBA revealed the covalent bonding between the Pd(Ⅱ) and the C-atoms in three-membered palladacycle intermediate species. Electrostatic potential analysis indicated that the regioselectivity of the reaction process is controlled by the charge distribution on the pallada(Ⅱ)cycle during the protonation step. The results presented herein contribute to a better understanding of transition metal-catalyzed alkyne transformations and provide a practical theoretical guide for further experimental investigation.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22003006, 21822303, 22103008, 22271034). Project supported by graduate research and innovation foundation of Chongqing, China (No. CYB20045). We are thankful for a project (No. 2018CDXZ0002) supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Chongqing University). We acknowledge Beijing PARATERA Tech CO, for providing HPC resources that have contributed to the research results reported within this paper. URL: http://cloud.paratera.com.

| [1] |

B.M. Trost, C.J. Li, Modern Alkyne Chemistry: Catalytic and At-Om-Economic Transformations. John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

|

| [2] |

V.P. Boyarskiy, D.S. Ryabukhin, N.A. Bokach, A.V. Vasilyev, Chem. Rev. 116 (2016) 5894-5986. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00514 |

| [3] |

J. Chen, J. Guo, Z. Lu, Chin. J. Chem. 36 (2018) 1075-1109. DOI:10.1002/cjoc.201800314 |

| [4] |

G. Fang, X. Bi, Chem. Soc. Rev. 44 (2015) 8124-8173. DOI:10.1039/C5CS00027K |

| [5] |

Y. Iyori, R. Ueno, A. Morishige, N. Chatani, Chem. Sci. 12 (2020) 1772-1777. |

| [6] |

S. Jeong, J.M. Joo, Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 4518-4529. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00547 |

| [7] |

M. Patel, R.K. Saunthwal, A.K. Verma, Acc. Chem. Res. 50 (2017) 240-254. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00449 |

| [8] |

N.E. Schore, Chem. Rev. 88 (1988) 1081-1119. DOI:10.1021/cr00089a006 |

| [9] |

C.-Y. Shi, L. Li, W. Kang, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 446 (2021) 214131. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214131 |

| [10] |

L. Zhang, Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 877-888. DOI:10.1021/ar400181x |

| [11] |

Y. Lan, Computational Methods in Organometallic Catalysis: From Elementary Reactions To Mechanisms. John Wiley & Sons, 2021.

|

| [12] |

F. Alonso, I.P. Beletskaya, M. Yus, Chem. Rev. 104 (2004) 3079-3159. DOI:10.1021/cr0201068 |

| [13] |

S.R. Chemler, P.H. Fuller, Chem. Soc. Rev. 36 (2007) 1153-1160. DOI:10.1039/b607819m |

| [14] |

A.M. Echavarren, C. Nevado, Chem. Soc. Rev. 33 (2004) 431. DOI:10.1039/b308768a |

| [15] |

Y.H. Lee, B. Morandi, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 6444-6448. DOI:10.1002/anie.201812396 |

| [16] |

T.E. Müller, M. Grosche, E. Herdtweck, et al., Organometallics 19 (1999) 170-183. |

| [17] |

R. Severin, S. Doye, Chem. Soc. Rev. 36 (2007) 1407-1420. DOI:10.1039/b600981f |

| [18] |

X.F. Wu, X. Fang, L. Wu, et al., Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 1041-1053. DOI:10.1021/ar400222k |

| [19] |

Y. Zheng, W. Zi, Tetrahedron. Lett. 59 (2018) 2205-2213. DOI:10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.04.057 |

| [20] |

Y. Dai, F. Wang, S. Zhu, L. Chu, Chi. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4074-4078. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.12.050 |

| [21] |

Z. Shi, W. Mao, Z. Yang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107488. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.05.002 |

| [22] |

L. Li, S. Wang, A. Jakhar, et al., Green Synth. Catal. 4 (2023) 124-134. DOI:10.1117/12.2660370 |

| [23] |

T. Liu, R. Duan, Y. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4281-4286. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.01.041 |

| [24] |

C. Jia, T. Kitamura, Y. Fujiwara, Acc. Chem. Res. 34 (2001) 633-639. DOI:10.1021/ar000209h |

| [25] |

I.U. Khand, G.R. Knox, P.L. Pauson, et al., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 (1973) 977. |

| [26] |

R.C. Larock, E.K. Yum, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113 (2002) 6689-6690. |

| [27] |

I. Moritanl, Y. Fujiwara, Tetrahedron Lett. 8 (1967) 1119-1122. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)90648-8 |

| [28] |

P.L. Pauson, Tetrahedron 41 (1985) 5855-5860. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91424-3 |

| [29] |

Q. He, L. Zhu, Z.H. Yang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 17989-17994. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c09877 |

| [30] |

N. Iqbal, D.S. Lee, H. Jung, E.J. Cho, ACS Catal. 11 (2021) 5017-5025. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.1c00536 |

| [31] |

S.J. Lou, Q. Zhuo, M. Nishiura, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 2470-2476. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c13166 |

| [32] |

A. Ogawa, T. Ikeda, K. Kimura, T. Hirao, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 (1999) 5108-5114. DOI:10.1021/ja983949i |

| [33] |

Y. Pang, G. Liu, C. Huang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 12789-12794. DOI:10.1002/anie.202004950 |

| [34] |

M. Suginome, M. Shirakura, A. Yamamoto, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (2006) 14438-14439. DOI:10.1021/ja064970j |

| [35] |

M.R. Uehling, R.P. Rucker, G. Lalic, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 8799-8803. DOI:10.1021/ja503944n |

| [36] |

T. Ichitsuka, T. Fujita, T. Arita, J. Ichikawa, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 7564-7568. DOI:10.1002/anie.201402695 |

| [37] |

B. Tian, P. Chen, X. Leng, G. Liu, Nat. Catal. 4 (2021) 172-179. DOI:10.1038/s41929-021-00574-5 |

| [38] |

B.M. Trost, G. Zhang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 7312-7316. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c01755 |

| [39] |

S.-S. Yan, Q. Fu, L.-L. Liao, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 374 (2018) 439-463. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2018.07.011 |

| [40] |

D. Yu, S.P. Teong, Y. Zhang, Coord. Chem. Rev. 293-294 (2015) 279-291. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2014.09.002 |

| [41] |

D.H. Zhang, X.Y. Tang, M. Shi, Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 913-924. DOI:10.1021/ar400159r |

| [42] |

W.T. Boese, A.S. Goldman, Organometallics 10 (2002) 782-786. |

| [43] |

K. Gao, P.S. Lee, T. Fujita, N. Yoshikai, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 12249-12251. DOI:10.1021/ja106814p |

| [44] |

R. Ghosh, X. Zhang, P. Achord, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 (2007) 853-866. DOI:10.1021/ja0647194 |

| [45] |

Y. Huang, C. Ma, S. Liu, et al., Chemistry 7 (2021) 812-826. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2021.02.018 |

| [46] |

J. Pinkas, I. Císařová, R. Gyepes, et al., Organometallics 27 (2008) 5532-5547. DOI:10.1021/om800691f |

| [47] |

M. Tobisu, N. Chatani, Chem. Soc. Rev. 37 (2008) 300-307. DOI:10.1039/B702940N |

| [48] |

D.J. Durand, N. Fey, Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 837-848. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00807 |

| [49] |

A. Furstner, P.W. Davies, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46 (2007) 3410-3449. DOI:10.1002/anie.200604335 |

| [50] |

M. Korb, S.A. Moggach, P.J. Low, Chem. Commun. 57 (2021) 4251-4254. DOI:10.1039/d1cc00605c |

| [51] |

Y. Lyu, N. Toriumi, N. Iwasawa, Org. Lett. 23 (2021) 9262-9266. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03606 |

| [52] |

O.J.S. Pickup, I. Khazal, E.J. Smith, et al., Organometallics 33 (2014) 1751-1761. DOI:10.1021/om500114u |

| [53] |

E.N. Bahena, S.E. Griffin, L.L. Schafer, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 20566-20571. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c10405 |

| [54] |

C.A. Bradley, I. Keresztes, E. Lobkovsky, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (2004) 16937-16950. DOI:10.1021/ja045072v |

| [55] |

F. Guérin, D.H. McConville, J.J. Vittal, Organometallics 16 (1997) 1491-1496. DOI:10.1021/om960964s |

| [56] |

K. Kaleta, F. Strehler, A. Hildebrandt, et al., Chem. Eur. J. 18 (2012) 12672-12680. DOI:10.1002/chem.201202188 |

| [57] |

W. Ma, C. Yu, T. Chen, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 46 (2017) 1160-1192. DOI:10.1039/C6CS00525J |

| [58] |

S. Ohta, N. Miura, K. Saitoh, et al., Organometallics 40 (2021) 2826-2835. DOI:10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00292 |

| [59] |

A.F. Orsino, M. Gutierrez Del Campo, M. Lutz, M.E. Moret, ACS Catal. 9 (2019) 2458-2481. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b05025 |

| [60] |

P. Yang, Y. Sun, K. Fu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202111778. DOI:10.1002/anie.202111778 |

| [61] |

Y. Hu, M. Bai, Y. Yang, Q. Zhou, Org. Chem. Front. 4 (2017) 2256-2275. DOI:10.1039/C7QO00702G |

| [62] |

T.S. Ito, S. Hasegawa, Y. Takahashi, Y. Ishii, J. Organomet. Chem. 73 (1974) 401-409. DOI:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)83840-1 |

| [63] |

Y. Lan, L. Deng, J. Liu, et al., J. Org. Chem. 74 (2009) 5049-5058. DOI:10.1021/jo900919v |

| [64] |

J. Marco-Martinez, V. Lopez-Carrillo, E. Bunuel, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 (2007) 1874-1875. DOI:10.1021/ja0685598 |

| [65] |

N. Martinez-Espada, M. Mena, A. Perez-Redondo, et al., Dalton Trans. 44 (2015) 9782-9794. DOI:10.1039/C5DT01200G |

| [66] |

M. van der Sluis, V. Beverwijk, A. Termaten, et al., Organometallics 18 (1999) 1402-1407. DOI:10.1021/om980913q |

| [67] |

L. Yu, L. Lv, Z. Qiu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 14009-14013. DOI:10.1002/anie.202005132 |

| [68] |

Gaussian 16, Revision A. 03, 2016 Wallingford CT.

|

| [69] |

V. Barone, M. Cossi, J. Tomasi, J. Comput. Chem. 19 (1998) 404-417. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199803)19:4<404::AID-JCC3>3.0.CO;2-W |

| [70] |

E. Cancès, B. Mennucci, J. Tomasi, J. Chem. Phys. 107 (1997) 3032-3041. DOI:10.1063/1.474659 |

| [71] |

M. Cossi, V. Barone, R. Cammi, J. Tomasi, Chem. Phys. Lett. 255 (1996) 327-335. DOI:10.1016/0009-2614(96)00349-1 |

| [72] |

A.D. Becke, J. Chem. Phys. 98 (1993) 5648-5652. DOI:10.1063/1.464913 |

| [73] |

A.D. Becke, E.R. Johnson, J. Chem. Phys. 123 (2005) 154101. DOI:10.1063/1.2065267 |

| [74] |

S. Grimme, S. Ehrlich, L. Goerigk, J. Comput. Chem. 32 (2011) 1456-1465. DOI:10.1002/jcc.21759 |

| [75] |

C. Lee, W. Yang, R.G. Parr, Phys. Rev. B 37 (1988) 785-789. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785 |

| [76] |

Q. Feng, X. Ma, W. Bao, et al., CCS Chem. 3 (2021) 377-387. DOI:10.31635/ccschem.021.202000725 |

| [77] |

F. Weigend, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8 (2006) 1057-1065. DOI:10.1039/b515623h |

| [78] |

F. Weigend, R. Ahlrichs, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7 (2005) 3297-3305. DOI:10.1039/b508541a |

| [79] |

X. Qi, Y. Lan, Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 2905-2915. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00075 |

| [80] |

X. Qi, Y. Li, R. Bai, Y. Lan, Acc. Chem. Res. 50 (2017) 2799-2808. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00400 |

| [81] |

C. Shan, L. Zhu, L.B. Qu, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (2018) 7552-7576. DOI:10.1039/c8cs00036k |

| [82] |

Y. Zhao, D.G. Truhlar, Theor. Chem. Acc. 119 (2008) 525. DOI:10.1007/s00214-007-0401-8 |

| [83] |

I. Mayer, Chem. Phys. Lett. 97 (1983) 270-274. DOI:10.1016/0009-2614(83)80005-0 |

| [84] |

I. Mayer, Int. J. Quantum. Chem. 29 (1986) 477-483. DOI:10.1002/qua.560290320 |

| [85] |

T. Lu, Q. Chen, Chemistry–Methods 1 (2021) 231-239. DOI:10.1002/cmtd.202100007 |

| [86] |

A. Ariafard, Z. Lin, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (2006) 13010-13016. DOI:10.1021/ja063944i |

| [87] |

R.F.W. Bader, Chem. Rev. 91 (2002) 893-928. |

| [88] |

T. Lu, F. Chen, J. Phys. Chem. A 117 (2013) 3100-3108. DOI:10.1021/jp4010345 |

| [89] |

A.J. Thom, E.J. Sundstrom, M. Head-Gordon, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 11 (2009) 11297-11304. DOI:10.1039/b915364k |

| [90] |

T. Lu, F. Chen, J. Comput. Chem. 33 (2012) 580-592. DOI:10.1002/jcc.22885 |

| [91] |

Y. Zhou, X. Zhang, H. Liang, et al., ACS Catal. 4 (2014) 1390-1397. DOI:10.1021/cs500208n |

| [92] |

A.V. Rozhkov, I.V. Ananyev, R.M. Gomila, et al., Inorg. Chem. 59 (2020) 9308-9314. DOI:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c01170 |

2023, Vol. 34

2023, Vol. 34