Tremendous advances have been achieved in low-valent main group chemistry during the past three decades. Benefit from the appropriate design of ligands and synthetic strategies, a variety of low-valent main group element compounds, such as carbenes [1-5], silylenes [6-10], germylenes [6, 7], borylenes [11], alanediyl [12], aluminyl anions [13], as well as boryl anions [14-17], which were long-considered as transient species have been synthesized and isolated in laboratory conditions. In this context, sterically and electronically demanding ligands are crucial, which affect not only the stability, but also the chemical and physical properties of such highly reactive species. Among them, N-heterocyclic ligand systems, such as β-diketiminato ("NacNac") [18, 19], ene-diamide [14, 20, 21], amidinate [22, 23], amidophosphine [24], as well as monodentate ligand, m-terphenyl [12, 25] are the most commonly utilized resulting from the facile modifiability of the ligand frameworks (Fig. 1).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Selected low-valent group 13 and group 14 element compounds supported by N-heterocyclic and m-terphenyl ligand systems. | |

Carboranes are a class of polyhedral boron-carbon molecular clusters, which have long been employed as versatile ligands for transition metals, leading to the formation of a new class of organometallic complexes with interesting structural features [26-33]. In contrast, carborane-based ligands were employed in main group chemistry only in recent years. On the other hand, carboranes can also be considered as an alternative ligand system for low-valent main group element compounds attributed to their exceptionally thermal and chemical stabilities, easy modifications at the cage carbon vertices, large spherical steric effects, as well as the exo-π-bonding interactions between low-valent main group elements and cage carbons [34-37]. This review summarizes recent achievements in the application of carborane-based ligands in low-valent group 13 and group 14 elements chemistry.

2. Application in low-valent group 13 elements chemistryBorylenes (R-B: ), the boron(I) derivatives analogous to carbenes, are extremely electron-deficient and reactive arising from their structural features, only one substituent, but two vacant orbitals. In fact, free borylenes have not been isolated thus far, nevertheless, a series of Lewis bases-stabilized borylenes were synthesized [38].

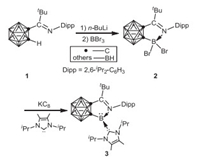

In 2015, Xie and coworkers investigated the application of o-carborane ligand in stabilization of borylenes by an iminocarborane 1 featuring an imino group attached to one cage carbon [39]. Treatment of 1 with n-BuLi in toluene, followed by the addition of BBr3 resulted in the formation of iminocarboranyldibromoborane 2. The desired iminocarboranylborylene 3 was prepared and isolated by reduction of 2 with potassium graphite in the presence of 1, 3-diisopropyl-4, 5-dimethylimidazole-2-ylidene in 57% yield (Scheme 1). Both X-ray analyses and density functional theory (DFT) calculations illustrate the presence of ligand-to-boron σ-donation and boron-to-ligand π-backdonation, which plays a crucial role for the stabilization of borylene 3.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Synthesis of iminocarboranylborylene. | |

The presence of a lone pair of electrons at boron implies the potential of 3 to behave as a Lewis base, however, no reactions of 3 were observed with various transition metals, such as Ni(COD)2, Pd(PPh3)4, Pd(dba)2 and ZnMe2 (COD = 1, 5-cyclooctadiene, dba = dibenzylideneacetone), probably because of the steric hindrance around boron. Nevertheless, the 2e− oxidation reaction of 3 with 2 equiv. of AgOAc in THF proceeded smoothly at room temperature, which afforded the formation of the expected trivalent boron compound 4 and silver metal [39]. To probe the above reaction process, the oxidation of 3 was assessed electrochemically, and the cyclic voltammogram of 3 shows a reversible 1e− oxidation at E1/2 = −1.09 V (versus Fc/Fc+), which implied the oxidation reaction might involve a radical cation intermediate. Indeed, the corresponding azaborolyl radical cations [5]2[Cu2I4] or [5][CuCl2] were obtained as NMR-silent dark red crystals by treatment of 3 with CuI or CuCl in THF at room temperature [40], in addition, the radical cations could be fully converted back to 3 via the reaction with K[CpFe(CO)2] (Scheme 2). DFT calculations show that the electron is delocalized over the BNC moiety, and the spin density is mainly localized at carbon (~73%) and boron (~25%). On the other hand, an unexpected oxidative deboration reaction was observed when 3 reacts with elemental sulfur in THF, leading to the formation of an unprecedented carbene-stabilized dicarbollyl-fused azaborole 6, rather than the compound with a "B = S" double bond [41-46]. Both X-ray analyses and DFT calculations clearly illustrate the existence of π-conjugation between the azaborole ring and dicarbollyl ring.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Oxidation of 3. | |

In 2017, the Xie group reported the reversible photothermal isomerization between 3 and borirane 7, an obvious color change was observed from deep purple to pale yellow, which afforded the first example of carborane-fused borirane 7 (Scheme 3) [47]. DFT calculations show that 3 is thermodynamically more stable compared to borirane. It was noteworthy that, this reaction brought about a new avenue to approach carborane-main group elements three-membered ring. The B-C(cage) bond of 7 can be broken via the reaction with CuCl, HCl or elemental sulfur, resulting in the formation of ring-open and ring-expansion products 8, 9 and 10, respectively (Scheme 3).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. Reversible photothermal isomerization between 3 and borirane 7. | |

3. Application in low-valent group 14 elements chemistry 3.1. Application in carbene chemistry

In 2014, Lavallo and coworkers reported the isolation of a series of carborane anions-fused N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) featuring two N-bound carborane anions via controllable selective deprotonation of an anionic imidazolium salt precursor 11, including two dianionic and a trianionic NHC lithium adducts 12, 13 and 14, respectively (Scheme 4) [48]. It is noteworthy that, 13 can be completely converted to 12 after heating the solution of 13 at 50 ℃ for 24 h, moreover, this isomerization can also be proton-catalyzed by 11. This study demonstrates that introduction of carboranes into NHC readily results in the change of chemical behavior, which undoubtedly broaden the NHC family.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 4. Synthesis of carborane anions-fused N-heterocyclic carbenes. | |

As an extension of this study, the Lavallo group subsequently reported the synthesis of unsymmetrical NHCs 16, 17 and 18 featuring one carborane N-substituent and one hydrocarbon N-substituent by controllable deprotonation of unsymmetrical zwitterionic imidazolium species 15 with bases, which was prepared by treatment of mesityl substituted oxazolinium cation with carborane anion amine, followed by reaction with acid (Scheme 5) [49]. Interestingly, an obvious directing effect induced by the carborane anion substituent was observed in the reaction of 15 with n-BuLi, which leads to the selective formation of dianionic C-2/C-5 NHC lithium adduct 18.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 5. Synthesis of unsymmetrical carborane anion-fused NHCs. | |

To investigate the ability of 12 and 16 to behave as viable ligands for transition metals, reactions of 12 and 16 with ClAuSMe2 in a 1:1 ratio were performed in fluorobenzene, which indeed afforded the expected zwitterionic and anionic gold carbene complexes 19 and 20, respectively (Scheme 6) [50].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 6. Synthesis of carborane anion-fused NHC Au(I) complexes. | |

In a related report [51], Lavallo and coworkers illustrated the suitability of the nido-carborane as an N-substituent for NHCs by isolation of an N-dicarbollide NHC 23 via step deprotonation of the precursor mono-nido-carboranyl imidazolium zwitterion 21, which was prepared via the reaction of anionic nido-amine with mesityl substituted oxazolinium cation, followed by treatment with HBF4 (Scheme 7). Recently, Xiao and coworkers reported the synthesis of nido-carborane anion fused imidazolium zwitterions by reacting of the amino o-carboranes with triethyl orthoformate and HBF4·Et2O [52].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 7. Synthesis of N-dicarbollide NHC dianion. | |

In 2020, the Lavallo group reported the synthesis of polyhalogenated carboranyl NHCs 26 and 27, by deprotonation of the corresponding polyhalogenated imidazolium anions, which were obtained by treatment of 11 with Br2 or ICl via selectively bromination or iodination (Scheme 8) [53]. As an exploration of the implementation of carboranyl NHCs, the Au(I) carbene complexes were found to behave as weakly coordinating anions (WCAs) and catalysts (Scheme 9).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 8. Synthesis of polyhalogenated carboranyl NHCs. | |

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 9. Synthesis of silver and iridium salts. | |

In 2016, Willans and coworkers reported the synthesis of a series of o-carboranyl imidazolium salts 33, 34, 35 and imidazolium nido-carborane zwitterion 36 by treatment of N-tbutyl or N-methylimidazole with bromoethylcarborane in toluene (Fig. 2) [54, 55], which showed unique and versatile coordination modes to give a series of o-carboranyl carbene rhodium, iridium and ruthenium complexes (Fig. 3).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Examples of o-carboranyl imidazolium salts and imidazolium nido-carborane zwitterion. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Examples of o-carboranyl carbene transition metal complexes. | |

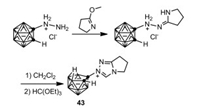

In 2017, Zeitler and coworkers reported a novel carboranyl-fused triazolium 43 through the reaction of carboranyl hydrazinium salt with lactim ether (Scheme 10) [56], which showed excellent catalytic activity in a wide range of C-C bond-forming reactions.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 10. Synthesis of carboranyl-fused triazolium. | |

3.2. Application in silylene chemistry

In 2016, Driess and coworkers demonstrated the isolation of o-carborane-substituted bis(silylene) 44 by treatment of o-carboranyl lithium salt with N, N'-di-tert-butyl(phenylamidinato)chlorosilylene [57, 58] in a 1:2 ratio [59] (Scheme 11). Similarly, in 2018, the Xie group reported the synthesis of a carborane-fused silylene 45 via the metathesis reaction of o-carboranyl lithium salt with N, N'-di-tert-butyl(phenylamidinato)chlorosilylene in a 1:1 ratio (Scheme 11) [60].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 11. Synthesis of o-carborane-substituted silylenes. | |

The Driess group investigated the reactivity of o-carborane-substituted bis(silylene) 44 toward carbon monoxide and 2, 6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide [61], whereby selective CO and isocyanide activation proceeded affording the head-to-head of CO and head-to-tail of isocyanide homocoupling products 46 and 47, respectively (Scheme 12).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 12. Reaction of 44 with carbon monoxide and 2, 6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide. | |

Compound 45 reacts with elemental sulfur and benzophenone resulting in the formation of the corresponding carborane-fused silanethione 48 and silaoxirane 49, respectively. On the other hand, treatment of 45 with 2-benzoylpyridine afforded the 2-benzoylpyridine homocoupling product 50 with a SiC2O2 five-membered ring (Fig. 4) [60].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Examples of carborane-fused silanethione and silaoxirane. | |

The Driess group investigated the o-carborane-substituted bis(silylene) 44 as a viable ligand for transition metals, which is confirmed by the formation of silylene nickel complexes 51 and 52, respectively (Fig. 5) [59].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Examples of o-carborane-substituted bis(silylene) nickel complexes. | |

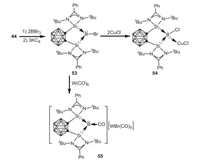

Apart from transition metal chemistry, o-carborane-substituted bis(silylene) 44 can also be utilized in main group chemistry. In 2017, Xie, Lin and coworkers reported the first example of bis(silylene)-stabilized bromoborylene 53 by reduction of bis(silylene)-BBr3 adduct with potassium graphite in THF at room temperature [62]. Bromoborylene 53 reacts with CuCl at room temperature resulting in the formation of the expected borylene-copper complex 54. In sharp contrast, treatment of 53 with W(CO)6 in THF at 80 ℃ afforded an unprecedented bis(silylene)-CO-stabilized borylene cation 55 (Scheme 13).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 13. Synthesis and reactivity of bis(silylene)-stabilized bromoborylene. | |

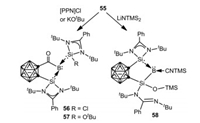

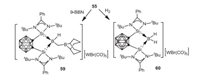

As an extension of this study, Xie, Lin and coworkers investigated the reactivity of 55 toward [PPN]Cl (PPN = Ph3P=N=PPh3), KOtBu, as well as LiN(SiMe3)2, whereby migration and complete cleavage of CO proceeded affording a series of novel silylene-stabilized carbonyl, silyl borylenes, 56, 57 and 58 respectively (Scheme 14) [63]. On the other hand, treatment of 55 with 9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane (9-BBN) gave a cationic borane 59 via CO reduction. It is noteworthy that, the borylene cation 55 can cleave dihydrogen to form the corresponding boronium species 60 (Scheme 15) [62].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 14. Reaction of 55 with nucleophiles. | |

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 15. Reaction of 55 with 9-BBN and dihydrogen. | |

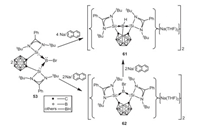

In 2018, Xie and coworkers investigated the reduction of bromoborylene 53 by 2 equiv. of sodium naphthalenide in THF, which leads to the formation of an unexpected diborane derivative 61 with a B-B(cage) single bond [64]. To probe the mechanism, reaction of 53 with 1 equiv. of sodium naphthalenide in THF was carried out, which affords a bis(silylene)-stabilized boron-centered radical cation 62 (Scheme 16). Further one electron reduction of 62 with sodium naphthalenide can also give 61. Based on the experimental and DFT calculations, insertion of in situ generated borylene into B(cage)-H bond resulting in the formation B-B single bond was proposed, which paves a new way for the synthesis of diborane derivatives featuring an electron-precise B-B single bond.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 16. Reduction of bromoborylene. | |

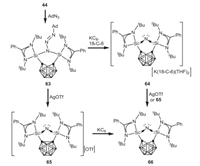

In 2020, Driess and coworkers reported the isolation of a remarkable bis(silylium) NI complex 63 featuring an open-cage dianionic nido-carborane through the reaction of o-carborane-substituted bis(silylene) 44 with adamantly azide [65]. One-electron reduction of 63 with potassium graphite leads to the formation of the remarkable bis(silylene)-stabilized NI complex 64 with the liberation of N2 and adamantine, and the regeneration of silylenes. On the other hand, one-electron oxidation of 63 with AgOTf affords the cationic bis(silylene) NI complex 65, which reacts with potassium graphite to form the neutral NI radical complex 66 (Scheme 17). In addition, 66 can be also achieved by treatment of 64 with AgOTf or 65.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 17. Synthesis of bis(silylene)-stabilized NI radical complex. | |

In 2020, the Driess group reported an o-carborane-substituted bis(silylene)-stabilized silylone 68 by treatment of dianionic nido-carboranyl bis(silylene) 67 with NHC-SiCl2 [66] (NHC = {[HCN(2, 6-iPr2C6H3)]2C: }) in THF [67]. It was noteworthy that, the dianionic nido-carboranyl bis(silylene) 67 behaved as a 2e− reductant in the above reaction. Additionally, one electron reduction of 68 results in the isolation of an unexpected bis(silylene)-stabilized [Si2]2+ complex 69 with a Si-Si bond via the homocoupling of an elusive bis(silylene)-stabilized SiI radical cation generated from the intramolecular one electron transfer from the Sio atom to the carborane cage (Scheme 18).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 18. Synthesis of bis(silylene)-stabilized silylone and [Si2]2+ complex. | |

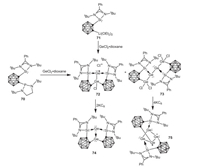

Very recently, Driess and coworkers reported the implementation of o-carborane-substituted silylene in low-valent germanium chemistry [68]. Treatment of o-carboranyl phosphine-silylene 70 with GeCl2·dioxane afforded the novel Ge2 and Ge4 complexes 72 and 73, respectively. Additionally, the Ge2 complex 72 can be also prepared via the reaction of o-carboranyl silylene lithium complex 71 with GeCl2·dioxane in good yield. Further reduction of complexes 72 or 73 with potassium graphite yielded the novel Ge2 complex 74 featuring a localized dative Ge(0)→Ge(II) bond or Ge4 complex 75 bearing a four-membered Ge4 ring with significant σ-electron delocalization over the Ge4 moiety (Scheme 19).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 19. Synthesis and reduction of the dinuclear germyl-germyliumylidine chloride and tetranuclear digermyl-digermylene. | |

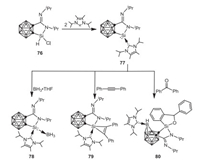

In 2017, Xie and coworkers reported the isolation of a carbene-stabilized cyclic amino(carboranyl) silylene 77 by treatment of cyclic amino(carboranyl) chlorosilane 76 with N-heterocyclic carbene [69]. While the reaction of 77 with borane leads to the formation of a Lewis acid-base adduct 78, the reactions of 77 with unsaturated molecules, such as diphenylacetylene and benzophenone afford cycloaddition products 79 and 80, respectively (Scheme 20).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 20. Synthesis and reactivity of carbene-stabilized cyclic amino(carboranyl) silylene. | |

Very recently, Driess and coworkers investigated the influence of the redox non-innocent carborane on the reactivity of an o-carborane-substituted bis(silylene) stabilized germylone 81 towards reductants and oxidants [70]. In this context, one electron oxidation of 81 with [Cp2Fe][B{C6H3(CF3)2}4] affords the GeI-GeI homocoupling product, bis(silylene)-stabilized diatomic Ge2 complex 82, while one electron reduction of 81 with potassium naphthalenide also results in the formation of the unexpected bis(silylene)-stabilized diatomic Ge2 complex 83 via one electron oxidation of Ge0 to GeI and two electron reduction of the carborane cage. Moreover, a neutral Ge2 complex 85 with a triplet diradical ground state was prepared by treatment of germylene-stabilized GeCl2 84 with potassium naphthalenide (Scheme 21).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 21. Synthesis of the novel Ge2 complexes. | |

3.3. Application in germylene and stannylene chemistry

In 2017, Xie and coworkers reported the synthesis of two iminocarboranyl germylenes 86 and 87 through the reactions of iminocarborane lithium salt with GeCl2·dioxane in a 1:1 ratio or 2:1 ratio [71]. Chlorogermylene 86 reacts with trimethylamine N-oxide or elemental sulfur in THF at room temperature to give the μ-oxo or μ-S dimer 88 and 89 featuring a four-membered Ge2O2 or Ge2S2 ring, respectively (Scheme 22). In addition, treatment of 86 with K[CpFe(CO)2] in toluene at room temperature afforded an iron-germylene complex 90.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 22. Synthesis and reactivity of iminocarboranyl germylenes. | |

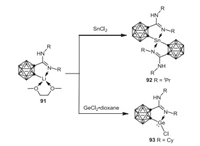

In 2010, the Edelmann group reported that N, N'-dialkylcarbodiimides reacts with o-carboranyl lithium complexes to form the lithium carboranylamidinate 91, which underwent metathesis reaction with anhydrous SnCl2 in THF in a 2:1 ratio to afford the o-carboranyl stannylene 92 [72]. In a similar manner, the chlorogermylene 93 was prepared by treatment of in situ formed 91 with GeCl2·dioxane in a 1:1 ratio (Scheme 23) [73].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 23. Synthesis of o-carboranyl stannylene and chlorogermylene. | |

4. Conclusions and perspectives

Employment of carborane-based ligands allowed the synthesis of a series of low-valent group 13 and group 14 element compounds with novel structure and reactivity via different synthetic routes, which indeed enriched the chemistry of low-valent main group element compounds. To date, a variety of carborane-based ligands supported borylenes, carbenes, silylenes, germylenes and stannylenes have been successfully synthesized whereby varied types of new chemical transformations are observed. These achievements indicate that both the carboranyl and ancillary ligands are critical for the stabilization of reactive low-valent main group element compounds. Notwithstanding, in comparison to the large amount of carboranyl transition metal complexes, the utilization of carborane-based ligands in low-valent main group chemistry is still in its early stage. On the other hand, the types of carborane-based ligands suitable for the stabilization of low-valent main group element compounds are scarce, which undoubtedly restrict the application of carborane-based ligands in the field of low-valent main group element chemistry. Furthermore, the reported carborane-based ligands are all cage carbon fused, the synthesis of cage boron involved ligands has still remained challenging.

The reported results show that the redox non-innocent character of carboranes can be served as reductants or oxidatants under different reaction conditions, which enables the adjustability of the electronic structure of low-valent main group element centers. Moreover, this unique electronic structure can enhance the ability of such carborane-based ligands supported low-valent main group element compounds to participate in the reactions involved multiple electrons transfer processes, such as catalysis and N2 activation. It is quite possible that carborane-based ligands supported low-valent main group element compounds can achieve the above-mentioned challenging tasks.

Additionally, the unique feature of carborane implies the structural diversity of carborane-based ligands, since both cage boron and cage carbon vertices can be fused in the ligand frameworks, which enable the flexibility in ligand design. In fact, design and synthesis of new types of carborane-based ligands are crucial for the development of this new and flourishing field. In addition, the fine design of carborane-based ligands may allow the development of low-valent main group element compounds that participate in those chemical transformations which were long dominant by transition metals, such as small molecule activation, catalysis.

Declaration of competing interestThe author declares that he has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsI am grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21901039), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20190327).

| [1] |

D. Bourissou, O. Guerret, F.P. Gabbaï, G. Bertrand, Chem. Rev. 100 (2000) 39-91. |

| [2] |

J. Vignolle, X. Cattoën, D. Bourissou, Chem. Rev. 109 (2009) 3333-3384. DOI:10.1021/cr800549j |

| [3] |

M. Melaimi, M. Soleilhavoup, G. Bertrand, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (2010) 8810-8849. DOI:10.1002/anie.201000165 |

| [4] |

M. Soleilhavoup, G. Bertrand, Acc. Chem. Res. 48 (2015) 256-266. DOI:10.1021/ar5003494 |

| [5] |

M. Melaimi, R. Jazzar, M. Soleilhavoup, G. Bertrand, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 10046-10068. DOI:10.1002/anie.201702148 |

| [6] |

Y. Mizuhata, T. Sasamori, N. Tokitoh, Chem. Rev. 109 (2009) 3479-3511. DOI:10.1021/cr900093s |

| [7] |

M. Asay, C. Jones, M. Driess, Chem. Rev. 111 (2011) 354-396. DOI:10.1021/cr100216y |

| [8] |

Y.P. Zhou, M. Driess, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 3715-3728. DOI:10.1002/anie.201811088 |

| [9] |

S. Fujimori, S. Inoue, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. (2020) 3131-3142. DOI:10.1002/ejic.202000479 |

| [10] |

C. Shan, S. Yao, M. Driess, Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (2020) 6733-6754. DOI:10.1039/d0cs00815j |

| [11] |

M. Soleilhavoup, G. Bertrand, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 10282-10292. DOI:10.1002/anie.201705153 |

| [12] |

J.D. Queen, A. Lehmann, J.C. Fettinger, H.M. Tuononen, P.P. Power, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 20554-20559. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c10222 |

| [13] |

J. Hicks, P. Vasko, J.M. Goicoechea, S. Aldridge, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 1702-1713. DOI:10.1002/anie.202007530 |

| [14] |

Y. Segawa, M. Yamashita, K. Nozaki, Science 314 (2006) 113-115. DOI:10.1126/science.1131914 |

| [15] |

H. Braunschweig, C.W. Chiu, K. Radacki, T. Kupfer, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (2010) 2041-2044. DOI:10.1002/anie.200906884 |

| [16] |

D.A. Ruiz, G. Ung, M. Melaimi, G. Bertrand, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52 (2013) 7590-7592. DOI:10.1002/anie.201303457 |

| [17] |

W. Lu, H. Hu, Y. Li, R. Ganguly, R. Kinjo, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (2016) 6650-6661. DOI:10.1021/jacs.6b03432 |

| [18] |

C. Cui, H.W. Roesky, H.G. Schmidt, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39 (2000) 4274-4276. DOI:10.1002/1521-3773(20001201)39:23<4274::AID-ANIE4274>3.0.CO;2-K |

| [19] |

M. Driess, S. Yao, M. Brym, C.v. Wüllen, D. Lentz, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (2006) 9628-9629. DOI:10.1021/ja062928i |

| [20] |

A.J. Arduengo, R.L. Harlow, M. Kline, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113 (1991) 361-363. DOI:10.1021/ja00001a054 |

| [21] |

M. Denk, R. Lennon, R. Hayashi, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116 (1994) 2691-2692. DOI:10.1021/ja00085a088 |

| [22] |

C.W. So, H.W. Roesky, J. Magull, R.B. Oswald, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45 (2006) 3948-3950.

|

| [23] |

S.S. Sen, H.W. Roesky, D. Stern, J. Henn, D. Stalke, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 1123-1126. DOI:10.1021/ja9091374 |

| [24] |

R. Rodriguez, D. Gau, Y. Contie, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50 (2011) 11492-11495. DOI:10.1002/anie.201105639 |

| [25] |

B.D. Rekken, T.M. Brown, J.C. Fettinger, H.M. Tuononen, P.P. Power, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134 (2012) 6504-6507. DOI:10.1021/ja301091v |

| [26] |

S.P. Fisher, A.W. Tomich, S.O. Lovera, et al., Chem. Rev. 119 (2019) 8262-8290. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00551 |

| [27] |

S.P. Fisher, A.W. Tomich, J. Guo, V. Lavallo, Chem. Commun. 55 (2019) 1684-1701. DOI:10.1039/c8cc09663e |

| [28] |

Z.J. Yao, G.X. Jin, Coord. Chem. Rev. 257 (2013) 2522-2535. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.004 |

| [29] |

F.T. Edelmann, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 639 (2013) 655-667. DOI:10.1002/zaac.201300014 |

| [30] |

O. Crespo, M.C. Gimeno, A. Laguna, J. Organomet. Chem. 694 (2009) 1588-1598. DOI:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2008.11.069 |

| [31] |

H. Shen, Z. Xie, Chem. Commun. (2009) 2431-2445. DOI:10.1039/b901549c |

| [32] |

Z. Xie, Coord. Chem. Rev. 250 (2006) 259-272. |

| [33] |

Z. Xie, Acc. Chem. Res. 36 (2003) 1-9. |

| [34] |

F. Zheng, J. Zhang, X. Fu, Z. Xie, Chem. Asian J. 8 (2013) 1886-1891. DOI:10.1002/asia.201300240 |

| [35] |

K. Chui, H.W. Li, Z. Xie, Organometallics 19 (2000) 5447-5453. |

| [36] |

L.A. Boyd, W. Clegg, R.C.B. Copley, et al., Dalton Trans. (2004) 2786-2799. |

| [37] |

J.M. Oliva, N.L. Allan, P.v.R. Schleyer, C. Viñas, F. Teixidor, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (2005) 13538-13547. DOI:10.1021/ja052091b |

| [38] |

M. Soleilhavoup, G. Bertrand, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 10282-10292. DOI:10.1002/anie.201705153 |

| [39] |

H. Wang, J. Zhang, Z. Lin, Z. Xie, Chem. Commun. 51 (2015) 16817-16820. DOI:10.1039/C5CC06818E |

| [40] |

H. Wang, J. Zhang, Z. Lin, Z. Xie, Organometallics 35 (2016) 2579-2582. DOI:10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00545 |

| [41] |

H. Dolati, L. Denker, B. Trzaskowski, R. Frank, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 4633-4639. DOI:10.1002/anie.202015553 |

| [42] |

S. Liu, M.A. Légaré, A. Hofmann, H. Braunschweig, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 11223-11226. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b07829 |

| [43] |

S. Liu, M.A. Légaré, D. Auerhammer, A. Hofmann, H. Braunschweig, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 15760-15763. DOI:10.1002/anie.201708729 |

| [44] |

P. Chen, C. Cui, Chem. Eur. J. 22 (2016) 2902-2905. DOI:10.1002/chem.201505182 |

| [45] |

D. Franz, E. Irran, S. Inoue, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 14264-14268. DOI:10.1002/anie.201407809 |

| [46] |

H. Wang, J. Zhang, H. Hu, C. Cui, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 10998-10999. DOI:10.1021/ja105021d |

| [47] |

H. Wang, J. Zhang, Z. Xie, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 9198-9201. DOI:10.1002/anie.201704642 |

| [48] |

A. El-Hellani, V. Lavallo, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 4489-4493. DOI:10.1002/anie.201402445 |

| [49] |

M.J. Asay, S.P. Fisher, S.E. Lee, et al., Chem. Commun. 51 (2015) 5359-5362. DOI:10.1039/C4CC08267B |

| [50] |

S.P. Fisher, A. El-Hellani, F.S. Tham, V. Lavallo, Dalton Trans. 45 (2016) 9762-9765. DOI:10.1039/C6DT00551A |

| [51] |

J. Estrada, V. Lavallo, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 9906-9909. DOI:10.1002/anie.201705857 |

| [52] |

Z. Cui, B. Wang, J. Li, et al., Chin. J. Chem. 39 (2021) 2410-2416. DOI:10.1002/cjoc.202100302 |

| [53] |

S.P. Fisher, S.G. McArthur, V. Tej, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 251-256. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b10234 |

| [54] |

J. Holmes, C.M. Pask, M.A. Fox, C.E. Willans, Chem. Commun. 52 (2016) 6443-6446. DOI:10.1039/C6CC01650B |

| [55] |

J. Holmes, C.M. Pask, C.E. Willans, Dalton Trans. 45 (2016) 15818-15827. DOI:10.1039/C6DT02079H |

| [56] |

C. Selg, W. Neumann, P. Lönnecke, E. Hey-Hawkins, K. Zeitler, Chem. Eur. J. 23 (2017) 7932-7937. DOI:10.1002/chem.201700209 |

| [57] |

C.W. So, H.W. Roesky, J. Magull, R.B. Oswald, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45 (2006) 3948-3950. DOI:10.1002/anie.200600647 |

| [58] |

S.S. Sen, H.W. Roesky, D. Stern, J. Henn, D. Stalke, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 1123-1126. DOI:10.1021/ja9091374 |

| [59] |

Y.P. Zhou, S. Raoufmoghaddam, T. Szilvási, M. Driess, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 12868-12872. DOI:10.1002/anie.201606979 |

| [60] |

H. Wang, J. Zhang, Z. Xie, J. Organomet. Chem. 865 (2018) 173-177. |

| [61] |

Y. Xiong, S. Yao, T. Szilvási, A. Ruzicka, M. Driess, Chem. Commun. 56 (2020) 747-750. DOI:10.1039/c9cc08680c |

| [62] |

H. Wang, L. Wu, Z. Lin, Z. Xie, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 13680-13683. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b08667 |

| [63] |

H. Wang, L. Wu, Z. Lin, Z. Xie, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 8708-8713. DOI:10.1002/anie.201802643 |

| [64] |

H. Wang, J. Zhang, H.K. Lee, Z. Xie, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 3888-3891. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b01795 |

| [65] |

S. Yao, T. Szilvási, Y. Xiong, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 22043-22047. DOI:10.1002/anie.202011598 |

| [66] |

R.S. Ghadwal, H.W. Roesky, S. Merkel, J. Henn, D. Stalke, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48 (2009) 5683-5686. DOI:10.1002/anie.200901766 |

| [67] |

S. Yao, A. Kostenko, Y. Xiong, A. Ruzicka, M. Driess, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 12608-12612. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c06238 |

| [68] |

Y. Xiong, D. Chen, S. Yao, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 6229-6237. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c01722 |

| [69] |

H. Wang, T.L. Chan, Z. Xie, Chem. Commun. 54 (2018) 385-388. DOI:10.1039/C7CC08690C |

| [70] |

S. Yao, A. Kostenko, Y. Xiong, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 14864-14868. DOI:10.1002/anie.202103769 |

| [71] |

H. Wang, Z. Xie, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. (2017) 4430-4435. DOI:10.1002/ejic.201700496 |

| [72] |

P. Dröse, C.G. Hrib, F.T. Edelmann, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 15540-15541. DOI:10.1021/ja108051u |

| [73] |

P. Liebing, N. Harmgarth, F. Zörner, et al., Inorganics 7 (2019) 41. DOI:10.3390/inorganics7030041 |

2022, Vol. 33

2022, Vol. 33