b State Key Laboratory of Environment-friendly Energy Materials, School of National Defence Science and Technology, Southwest University of Science and Technology, Mianyang 621010, China;

c College of Chemistry, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610064, China;

d School of Physics and Astronomy, China West Normal University, Nanchong 637002, China;

e NHC Key Laboratory of Nuclear Technology Medical Transformation, Mianyang Central Hospital, Mianyang 621010, China

Nuclear energy is regarded as one of the most effective solutions to solve the shortage of fossil energy and environmental problems because of its high energy density and without-producing greenhouse gas [1]. As a long half-life nuclide, radionuclide uranium is mainly produced in spent fuel reprocessing process. Its high chemical toxicity and radioactivity result in a threat to human health and environmental safety, which places higher demands on environmental pollution remediation and prevention [2]. Thus, how to safely and efficiently remove U(Ⅵ) from wastewater has become a concern of the public and scientific community. Until now, there are many technologies which have been developed for treatment and removal of U(Ⅵ) including adsorption, ion exchange and chemical reduction [3]. Among them, adsorption technology has been popularized and applied for its cost-effectiveness and simple operation [4, 5]. To be specific, adsorption materials such as layered double hydroxides (LDHs) [6] and metal organic frameworks (MOFs) [7] have been used to efficiently remove uranium in wastewater. However, the recovery and reuse of LDHs and the high cost of MOFs limit their further application. Therefore, polymeric carbon nitride (PCN) with its easier-functionalization and unique electronic property has attracted more attention as a uranium adsorption material in recent years [8].

Graphitic C3N4 (g-C3N4) is one of the most stable allotropes of polymeric carbon nitride with simple modification and abundant electron density, which has been widely used in adsorption in the past [9]. Generally, g-C3N4 is used to adsorb radionuclides by adding or releasing adsorption sites by compounding with other materials or grafting functional groups, and the directional chemical structure modification of g-C3N4 can increase active sites so to bring special characteristics [10-12]. Vinu et al. found that adding additional nitrogen-rich units to the g-C3N4 framework to increase the N/C ratio in carbon nitride from 1.3 to 1.6–1.8 could expand the conjugate network and electron density. The precursor aminoguanidine hydrochloride was used to synthesize mesoporous carbon nitride (MCN-4) with high nitrogen content through the hard template method. MCN-4 had a lower band gap and a larger specific surface area, and it could be a highly active catalyst in friedel–crafts acylation of benzene using hexanoyl chloride as the acylating agent [13-15]. Sasanka et al. used the precursor dicyandiamide and the template SBA-15 to synthesize mesoporous carbon nitride nanodomains (MDY) with g-C3N4.7 stoichiometry by the hard template method, showing excellent performance in the photocatalytic hydrogen precipitation [16]. Liu et al. used PVP and NH4Cl to synthesize N-doped carbon (NCG) with high nitrogen content through the one-pot pyrolysis of melamine, showing excellent adsorption performance for methylene blue [17]. Furthermore, Wu et al. [18] and Kumar et al. [19] used melamine pretreatment to synthesize C3N5 with a new stoichiometry, which also showed excellent adsorption photoreduction activity. However, these nitrogen-rich carbon nitrides research seem to be more focused on the field of catalysis or removal of dye pollutants, the research of nitrogen-rich carbon nitrides for radionuclide uranium absorption is still quite scarce.

Today, some researchers have found that nitrogen-rich materials or nitrogen-containing functional groups have a good capture effect on radionuclides, such as uranium. Wang et al. prepared N-doped porous magnetic materials (N-doped Fe/Fe3C@C) by hydrothermal method using dopamine as the N source, which improved their adsorption properties on uranium and recyclability [20]. The same group also synthesized fabricate cotton-like graphitic carbon nitride@layered double hydroxides nanocomposites (g-C3N4@Ni-Mg-Al-LDH) by a mild hydrothermal process. The synergistic effect of carbon nitride and LDH enhanced the capture of UO22+ [21]. Wang et al. prepared metal-organic framework (UiO-66-AO) appended amidoxime by post synthetic modification method for extraction of uranium from seawater. It demonstrated very fast adsorption kinetics and high adsorption capacity of uranyl ion, also suggesting multiple amidoxime ligands can chelate U(VI) ions [22]. Furthermore, they found the placement of amidoxime chelating groups on MXene surface by diazonium salt grafting can enhance the selectivity for uranyl ions, and improve their stability in aqueous solution [23]. Qiu et al. fabricated amidoxime/carbon nitride (AO/g-C3N4) for capturing U(VI) from nuclear wastewater and seawater. It exhibited the high uranium extraction capacity from natural seawater and excellent selectivity [24]. Chen et al. report a sunlight-driven photocatalysis-assisted extraction (SUPER) method by utilizing a bifunctional carbon nitride material, CN550. Compared with the pure physicochemical adsorption (PA) method, a tenfold higher uranium extraction capacity [25].

Here, we firstly reported the removal of uranium using the nitrogen-rich carbon nitride polymer with C3N5 stoichiometry and explored its adsorption mechanism. Compared with g-C3N4, the heptazine unit is connected through an azo bridge in the C3N5 structure, which increases the conjugated system of the material, and its high electron density of states enhances the electrostatic bonding ability. The results show that C3N5 can capture uranyl ions by a combination of physical adsorption with chemical adsorption, also have high kinetic characteristics for uranyl ions, which only costs 10 min to adsorb 100 mg/g U(VI). Besides, it can achieve complete adsorption balance in 60 min with maximum adsorption capacity 207 mg/g. In addition, it shows high selectivity in presence of excess of competitive ions and good recyclability. Combining theoretical and experimental results, this work provides a method to improve the adsorption performance of carbon-nitrogen polymers on uranium by nitrogen-enrichment treatment and sheds light on the design and development of nitrogen-rich carbon nitride polymer for application in the separation and enrichment of uranium.

As illustrated in Fig. S1 (Supporting information), C3N5 is synthesized by melamine thermal polymerization and deamination (see Supporting information for experimental details). In order to explore the morphology of the prepared C3N5, we characterized SEM and TEM images. As shown in Fig. 1a and Fig. S2 (Supporting information), the prepared C3N5 has a porous overall structure, which is different from the traditional g-C3N4 block structure. And the TEM of C3N5 (Fig. 1b) further demonstrates the characteristics of the material being stacked in layers. The wider diffraction ring is seen in the selected area electron diffraction (SARD) of C3N5 corresponds to the 002 plane of the material, and it shows that the material is amorphous (Fig. 1c).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. SEM of C3N5 (a), HR-TEM of C3N5 (b, c), right inset showing SAED diffraction pattern. | |

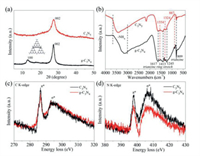

In order to research the crystal mode information, we performed XRD characterization on the prepared C3N5 and g-C3N4. The difference in the structure of phases and changes in the crystalline property of the C3N5 precursor are shown in Fig. S3 (Supporting information) [26]. As shown in Fig. 2a, the XRD spectrum of g-C3N4 shows two peaks at around 12.9° and 27.3° indexed to the (100) and (002) planes, which the former corresponds to the in-planar structural packing of the motif, and the latter can be ascribed to the interplanar stacking of the sheets [27, 28]. The XRD spectrum of C3N5 only shows one peak at 27.5° corresponded to (002) plane, and there is no peak corresponding to (100) plane. It is proved that the distortion of the C3N5 grid structure also means that the bridging of the azo bond to the heptazine unit makes the nanochannel distance between heptazine larger [29]. These XRD results clearly support the distinct structure of C3N5 possessing azo linkage. The slight increase in the 2θ value and d spacing can be explained by the repulsion between the electron-rich π-conjugated C3N5 sheets [30]. Additionally, the changes in the functional groups on the surface of the original g-C3N4 and C3N5 were further studied by FT-IR spectroscopy (Fig. 2b). The changes in the preparation of C3N5 precursors are shown in Fig. S4 (Supporting information). The peaks of C3N5 and g-C3N4 at 809 cm−1 are all attributed to the characteristic peaks of the triazine ring, which is consistent with the literature reports [27]. The peaks at 1617, 1413 and 1245 cm−1 are basically the same as g-C3N4, indicating that the basic building blocks are still triazine units [31]. However, the difference between C3N5 and g-C3N4 infrared spectra at 887, 1324 and 1554 cm−1 indicate that C3N5 and g-C3N4 have completely different grid structures [19]. As for C3N5, since the azo bond is forbidden to vibrate, no new vibration peaks have been found due to azo. We also tested the N2 sorption/desorption isotherm of C3N5 and g-C3N4 (Fig. S5 in Supporting information), there is no significant difference in the specific surface area of C3N5 and g-C3N4, which are 7.04 m2/g and 7.3 m2/g, respectively. Moreover, it is tested that the bonding performance and electronic structure of C and N in the material by measuring the electron energy loss spectrum (EELS).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. XRD diffraction spectra (a) and FTIR spectra (b) of g-C3N4 and C3N5; Normalized EELS spectra of g-C3N4 and C3N5 for (c) C K-edge and (d) N K-edge loss. | |

As shown in Fig. 2c, two symmetrical peaks at 286.6 eV and 293.1 eV were appeared in the normalized EELS spectra of C3N5 and g-C3N4 due to C K-edge loss, corresponding to the 1s-π* and 1s-σ* electronic transitions of the sp2 hybrid carbon trigonally bonding with N in the s-heptazine nucleus [32, 33]. The C K-edge intensity of π* belonging to C3N5 and the peak area ratio of π*/σ* of C3N5 are slightly higher, indicating that the superposition of the π orbitals of the bridged azo group in C3N5 structure and the heptazine sequence leads to increased conjugation, and such an increased conjugation also leads to higher electron density in C3N5 than in g-C3N4 [34]. This is also demonstrated by the calculation of the surface charge density distribution. In contrast to the electron density dispersion at the bridge linkage of g-C3N4, the electron density at the bridge linkage of C3N5 is more concentrated due to the azo. Meanwhile, the N K edge peaks of C3N5 and g-C3N4 are located at 397.8 eV and 406.3 eV (Fig. 2d), which are attributed to the sp2 hybrid nitrogen and bridging nitrogen in the heptazine unit [35]. The electronic states of N of the two are basically similar, but the peak area of C3N5 was increased slightly relative to g-C3N4, which might be because of the extra nitrogen in the framework. Since the electronic transition caused by the azo motif makes a greater contribution to the 1s-σ* transition, the relative peak intensity of the π* signal at the N K edge of C3N5 is reduced [14]. The N(C)3 of g-C3N4 passes through the azo to form a lone pair on the azo, which suppresses the relative strength of the π* and σ* signals.

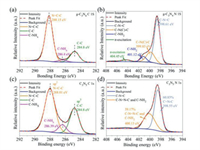

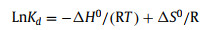

Moreover, XPS spectra were obtained to further confirm the functional information on pristine g-C3N4 and C3N5. From Fig. S6 (Supporting information), the XPS elemental survey scan of g-C3N4 and C3N5 shows peaks corresponding to C 1s, N 1s, O 1s and C 1s, N 1s, Na 1s, O 1s, respectively. The presence of Na 1s of C3N5 comes from intercalated Na+ ions in the supramolecular cavity of the C3N5 motif. As shown in Fig. 3a, the high-resolution of spectrum for C 1s of g-C3N4 can be deconvolved into three components at binding energies of 284.8 eV, 286.4 eV and 288.15 eV, corresponding to C-C coordination of surface adventitious carbon, C-NHx (x = 1, 2) on the edges of heptazine units and the sp2 hybrid N=C-N in the stronger tri-s-triazine ring [36, 37]. The spectrum for N 1s of g-C3N4 (Fig. 3b) includes four peaks at binding energies of 396.61 eV, 399.83 eV, 401.12 eV and 404.45 eV, corresponding to the N (C-N=C) bonded to two sp2 hybrid carbons in the g-C3N4 framework, the N (C-N(C)-C) connected to the three sp2 hybrid carbons in the tri-s-triazine ring, the residual N-H bond at the edge of g-C3N4, and the charged effect caused by π excitation, respectively [38, 39]. The high-resolution of spectrum for C 1s of C3N5 (Fig. 3c) is deconvolved into three components at binding energies of 284.8 eV, 286.39 eV and 287.9 eV, corresponding to the sp3 hybrid carbons, C-NHx (x = 1, 2) on the edges of heptazine units and sp2 hybrid carbons, respectively [36]. The sp3 carbon corresponds to the exogenous carbon, turbostratic carbons and the edge carbon in the scaffold of the C3N5 framework, while the stronger sp2 carbon corresponds to the N=C-N in the C3N5 framework [18]. In addition, the difference for C 1s of C3N5 is slightly lower (0.14 eV) at the sp2 hybrid carbon N=C-N bond at 288.01 eV compared to g-C3N4, indicating that the charge density on the nitrogen-containing heterocycle of C3N5 is greater. Zeta potential test results also provide support for this view (Fig. S7b in Supporting information). The spectra for N 1s of C3N5 (Fig. 3d) can be divided into two components at binding energies of 398.55 eV and 400.13 eV. The peak at 398.55 eV could be ascribed to C-N=C and C-N(C)-C in the aromatic ring structure of C3N5, while the other peak at 400.13 eV corresponds to bridged C-N=NnullC and residual C-NH2 [19]. There is an obvious bridging C-N=NnullC peak instead of N-(C)3 in N 1s region of C3N5, which shows that the connection mode of each unit of C3N5 is azo bond connection instead of N-(C)3 bond connection. Since the precursor MH of C3N5 have undergone the reaction of melem and hydrazine hydrate to convert amino groups into hydrazine groups, there are fewer residual amino groups in the N 1s of C3N5, which are separated to 400.13 eV. Furthermore, the N on the aromatic ring and the bridging N account for 60.83% and 39.17%, respectively, and their ratio is 3:2, which indicates that the two heptazine units are connected through one azo. The XRD, FT-IR and XPS results reveal that the C3N5 with a heptazine structure was successfully synthesized.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. The high resolution XPSspectra of C 1s and N 1s of g-C3N4 (a, b) and C3N5 (c, d). | |

As we know, the aqueous speciation of U(VI) in an aqueous solution is greatly affected by solution pH (Fig. S7a in Supporting information). When pH < 4, U(Ⅵ) exists as free UO22+ cations, with the increase of pH, it is dominated by multi-nuclear hydroxide complex cations, such as (UO2)2(OH)22+, (UO2)3(OH)5+, which may affect the adsorption behavior. Hence, the adsorption experiments of U(Ⅵ) on g-C3N4 and C3N5 under different pH (2–5.5) were carried out (Fig. 4a). It can be seen that with the increase of pH, the removal ratio of U(VI) by C3N5 gradually increases from 5% to a maximum of 99% at pH 4, but decreases as the pH continues to go up. As for g-C3N4, no matter how the pH changes, it has almost no adsorption performance for U(VI). This phenomenon does not only come from the change of species, but also be affected by the surface potential of the material. C3N5 has a lower surface potential than g-C3N4 due to the increase in electron density, which are −18.76 mV and 23.67 mV at pH 4, respectively (Fig. S7b). Thus, the adsorption performance of C3N5 is better than that of g-C3N4 during the experimental pH range because of the electrostatic interaction force. Taking account of the better adsorption performance and U(VI) hydrolysis caused by excessively high pH, the subsequent adsorption experiments were carried out at a pH value of 4.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. The comparison for adsorption performance of uranium by g- C3N4 and C3N5. (a) Effect of pH on U(VI) adsorption; (b) Adsorptionkinetics for U(Ⅵ); (c) Adsorptionisotherms for U(VI); (d) U(VI) sorption onto C3N5 at different; (e) Selective sorption of U(VI) with C3N5; (f) The reusability C3N5 for U(VI) sorption. | |

To better clarify the performance differences between C3N5 and g-C3N4 in adsorption of U(Ⅵ), adsorption kinetics experiments and adsorption isotherm studies were being carried out. As depicted in Fig. 4b, the uranium capture by g-C3N4 is sluggish and almost inefficient, with the removal efficiency of uranium achieving 4% after 8 h. While the adsorption equilibrium time of C3N5 is relatively faster, the removal efficiency of uranium can reach more than 75% in 10 min, and the adsorption equilibrium can be reached at near 30 min (Fig. S8 in Supporting information). The sorption kinetics curve of C3N5 and g-C3N4 towards U(Ⅵ) can be well fitted to the pseudo-second-order model (Fig. S9 and Table S1 in Supporting information), which means that the pseudo-second-order kinetic model is more suitable to describe the adsorption of U(Ⅵ) on C3N5 and g-C3N4, and further shows that the process is controlled by chemical adsorption. The adsorption isotherm studies were determined by adjusting the initial concentration of U(Ⅵ) from 10 ppm to 500 ppm at a constant pH of 4.0 ± 0.1. As shown in Fig. 4c, the maximum adsorption capacity of C3N5 to U(VI) is 207 mg/g, while the g-C3N4 to U(VI) is about 50 mg/g. Obviously, the adsorption performance of C3N5 for U(VI) is much higher than that of g-C3N4, which is about 4.1 times that of g-C3N4. The sorption isotherms curve of C3N5 and g-C3N4 towards U(Ⅵ) can be well fitted to the Langmuir model and Freundlich model, respectively (Fig. S10 and Table S2 in Supporting information). These results reveal the monolayer adsorption of U(Ⅵ) on C3N5 and multilayer adsorption reaction on g-C3N4.

To further understand the nature of the sorption process, the adsorption of U(VI) by C3N5 sorbent at different temperatures was performed, and the results were shown in Fig. 4d. It can be seen that the adsorption capacity of C3N5 to U(VI) gradually increases with the increase of temperature, indicating that higher temperature is more beneficial to the adsorption. It is known that the dependence of adsorption on temperature is related to changes in thermodynamic parameters, which are standard enthalpy (ΔH0), standard entropy (ΔS0), standard free energy (ΔG0), these can be calculated by the following equations:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

where Kd is the distribution coefficient (mL/g), R is the gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1) and T is the absolute temperature (K). The results were shown in inset of Figs. 5a and d and Table S3 (Supporting information). The positive value of ΔH0 (21.04 kJ/mol) indicates that the adsorption process is an endothermic reaction, and the negative value of ΔG0 indicates that the adsorption process can proceed spontaneously. Besides, the more negative values of ΔG0 at higher temperature further confirm that the higher temperature promotes the progress of the adsorption reaction.

|

Download:

|

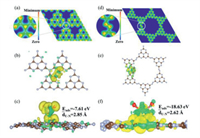

| Fig. 5. Isosurface plot of the electron charge density for g-C3N4 (a) and C3N5 (d). DFT theoretical calculation of adsorption position Ⅱ: top view (b) and side view (c) of isosurface plot of the electron charge density difference for g-C3N4-U. The top view (e) and side view (f) of isosurface plot of the electron charge density difference for C3N5-U (green signifies the negative; yellow represents positive); Brown: N atom, Gray: C atom, Blue: U atom, Red: O atom. | |

In order to investigate the practical application potential of the material, the selective experiment and cyclic experiment of C3N5 to uranium were carried out. The U(VI) solution was added with excessive amounts of metal ions in the form of nitrates, such as La3+, Nd3+, Sm3+, Gd3+, Yb3+, Sr2+, Ni2+, Co2+ and Zn2+ ions, whose concentration shows 10 times than that of U(VI) [40]. The removal rate of U(VI) by C3N5 can reach 57.4% in the system with excess metal ions (Fig. 4e) while the removal rate of other ions is at a very low level. Compared with the removal ratio of 63.2% in the blank experiment (Fig. S11 in Supporting information), there was no significant change. It indicates that competing ions have no obvious inhibitory effect on the uptake of uranium and also shows that C3N5 has good selectivity to U(VI). The reason for the selectivity may be on the electronegativity of different metal ions. The solution-phase electronegativity is a description of the strength of the electron absorption process of metal ions in aqueous solution, and the order of change of electronegativity of metal ions might be Sr2+ < Co2+ < Ni2+ < Zn2+ < La3+ < Nd3+ < Gd3+ < Sm3+ < Yb3+ < UO22+ [41, 42]. In addition, C3N5 exhibits high consistency in the continuous adsorption process (Fig. 4f). It can be seen that the U(VI) sorption by the regenerated C3N5 does not obviously decrease even after 5 cycles (> 85%), which suggests excellent reusability of the sorbent.

Furthermore, to theoretically investigate the structure, adsorption energy, differential charge, and charge density for C3N5 and g-C3N4. The g-C3N4 and C3N5 structures were optimized for cell expansion of 2 × 2 × 1 size, and 2 × 2 × 1 supercell structures were formed by cutting along the (001) crystal plane (Fig. S12 in Supporting information). We analyzed the distribution of the charge density surface of g-C3N4 and C3N5 at adsorption position Ⅱ, which was shown in Figs. 5b, c, e and f. The isosurface of the electron density difference was plotted at a value of 0.0037 electrons/Å3, and the yellow and green isosurfaces representing the charge accumulation and depletion regions, respectively. It can be clearly seen that compared with the g-C3N4, there is obvious charge transfer in the C3N5, and the latter one shows higher adsorption energy in Tables S4 and S5 (Supporting information). Besides, the average bond length of U-N of C3N5-U is generally smaller than that of g-C3N4-U, indicating that C3N5 can form stronger interactions with uranyl ions than g-C3N4. By comparing the adsorption energies and U-N distances of g-C3N4 and C3N5 at three different adsorption positions (Figs. S13 and S14 in Supporting information), we found that C3N5 always exhibits a stronger adsorption capacity for uranyl ions regardless of the adsorption position. In addition, the apparent charge transfer differences at the Ⅲ adsorption positions may result in C3N5, possessing more adsorption sites than g-C3N4. All in all, the DFT calculation results are in accordance with the above experimental results.

To explain the adsorption mechanism, the FTIR spectra and XPS were conducted for pristine and U(VI)-adsorbed samples (g-C3N4 and C3N5) (Fig. 6). Obviously, no peak of U 4f and characteristic stretching bond of UO22+ were found in the g-C3N4-U (uranium-loaded g-C3N4 after sorption) sample (Figs. S15 and S16 in Supporting information). As shown in Figs. 6a and b, the XPS spectra for C 1s and N 1s of g-C3N4 before and after adsorption have almost no shape change and shift, which proves that there is no interaction between g-C3N4 and U(VI). On the contrary, a new peak at 933 cm−1 on C3N5-U (uranium-loaded C3N5 after sorption) of FTIR spectra, which is a characteristic stretching bond of UO22+, confirms the fact of U(VI) adsorption, while there is no change in the characteristic peak of the triazine, indicating that the basic framework of the material is well maintained (Fig. 6f). As shown in Fig. S17 (Supporting information), the XPS elemental survey scan of C3N5-U shows a new peak corresponding to U 4f, which also explains the adsorption of U(VI).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. The comparison for high resolution XPSspectra of C 1s (a) and N 1s (b) of g-C3N4 and g-C3N4-U; C 1s (c) and N 1s (d) of C3N5 and C3N5-U; The high resolution XPS spectra of U 4f (e) of C3N5-U; (f) The before and after adsorption of FTIR spectra for C3N5. | |

As shown in Fig. 6c, compared with the C 1s spectra in the two samples, it is observed that the peak located at 288.01 eV for C3N5 become wider and moved 0.29 eV to higher binding energy after loading with uranium for C3N5-U. Meanwhile, the N 1s spectra peak locates at 398.55 eV and 400.13 eV for C3N5 moves 0.31 and 0.3 eV to higher binding energy after loading with uranium for C3N5-U, respectively (Fig. 6d). These indicate the decrease of electron density on the bridged azo and heptazine rings in the C3N5 skeleton after loading of U(VI). The high-resolution of U 4f5/2 and U 4f7/2 spectra contains several single peaks at 392.9, 390.9 eV and 384.74, 382.05, 379.96 eV, respectively (Fig. 6e). The peak at 390.9 and 379.96 eV correspond to U(IV), which shows the part of U(VI) is reduced to U(IV) during the adsorption process, when the relative ratio of U(IV) was calculated to be 13.2% in samples [43]. Besides, the uranium adsorbed on C3N5 exists mainly in the UO3·2H2O and (UO2)4O(OH)6(H2O)5 form of U(VI), indicates that the uranyl ion forms coordination with negative oxygen and hydroxide ions in solution in the presence of C3N5 (Fig. S18 in Supporting information). The main mechanism for the formation of these complexes may be from the electron-rich property of C3N5 trapping the hydrogen ions in solution and increasing the concentration of hydroxide ions in the system, leading to the complexation of excess hydroxide ions with UO22+. The results testify that strong chemical interaction and electron transfer happened between uranyl and the bridged azo on C3N5, which indicated that the excess electrons on the C3N5 backbone are transferred to the surface adsorbed uranyl during the adsorption process to reduce it from U(VI) to U(IV). On the other hand, many adsorption processes are related to the surface potential of material, the lower surface potential of C3N5 and change in electron density before and after adsorption suggest that electrostatic adsorption is also a possible mechanism.

In conclusion, we synthesized a new carbon nitride polymer with C3N5 stoichiometric for the removal of uranium. The C3N5 backbone composed of azo-bridged heptazine units which had a strong conjugation system and high electron density for the generation of additional lone pairs of electrons. Compared to conventional carbon nitrogen polymers (g-C3N4), the nitrogen-rich C3N5 had several advantages including high adsorption capacities and rapid kinetics. Meanwhile, C3N5 exhibited excellent selectivity for the UO22+ ion against hard ions such as Gd3+, Yb3+, Ni2+ and Sr2+. In addition, it can be recycled by a low-cost and environmentally friendly approach. The results of spectral analysis and theoretical calculations elucidated the mechanism of nitrogen enrichment for enhancing the physicochemical properties and the ability to capture uranium in carbo nitride polymers. Therefore, this work indicated that C3N5 has great promise and application in the separation and enrichment of uranyl ions, and also provides a reference for the systematic investigation of the adsorption ability of nitrogen-rich carbon nitrogen polymers on uranyl ions.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U2167221, 21976148, 21906133, 21902129); the Basic Scientific Research Project of China (No. JCKY2018404C008); the National key research and development Project of China (No. 2016YFC1402500); the Project of State Key Laboratory of Environment-friendly Energy Materials, Southwest University of Science and Technology (No. 18ZXHK04); the Long Shan Talent Project (Nos. 18LZX304, 18LZXT04).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.097.

| [1] |

S. Chu, A. Majumdar, Nature 488 (2012) 294-303. DOI:10.1038/nature11475 |

| [2] |

R. Taylor, Chem 1 (2016) 662-663. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2016.10.004 |

| [3] |

Y. Xie, C. Chen, X. Ren, et al., Progress Mater. Sci. 103 (2019) 180-234. DOI:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.01.005 |

| [4] |

B. Zhang, H.Y. Sun, J. Li, et al., Inorg. Chem. 58 (2019) 11622-11629. DOI:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01531 |

| [5] |

X. Qin, W. Yang, Y. Yang, et al., Inorg. Chem. 59 (2020) 9857-9865. DOI:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c01072 |

| [6] |

D. Yang, S. Song, Y. Zou, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 323 (2017) 143-152. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2017.03.158 |

| [7] |

B. Zhao, L. Yuan, Y. Wang, T. Duan, W. Shi, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13 (2021) 16300-16308. DOI:10.1021/acsami.1c00364 |

| [8] |

Z. Zhou, Y. Zhang, Y. Shen, S. Liu, Y. Zhang, Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (2018) 2298-2321. DOI:10.1039/c7cs00840f |

| [9] |

W.J. Ong, L.L. Tan, Y.H. Ng, S.T. Yong, S.P. Chai, Chem. Rev. 116 (2016) 7159-7329. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00075 |

| [10] |

G. Xiao, Y. Wang, S. Xu, et al., Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 27 (2019) 305-313. DOI:10.1016/j.cjche.2018.09.028 |

| [11] |

R. Gusain, N. Kumar, S.S. Ray, Coordin. Chem. Rev. 405 (2020) 213111. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2019.213111 |

| [12] |

C. Chang, W. Chen, Y. Chen, et al., Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 37 (2021) 2108017. DOI:10.3866/pku.whxb202108017 |

| [13] |

S.N. Talapaneni, G.P. Mane, A. Mano, et al., ChemSusChem 5 (2012) 700-708. DOI:10.1002/cssc.201100626 |

| [14] |

G.P. Mane, S.N. Talapaneni, K.S. Lakhi, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 8481-8485. DOI:10.1002/anie.201702386 |

| [15] |

I.Y. Kim, S. Kim, X. Jin, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 17135-17140. DOI:10.1002/anie.201811061 |

| [16] |

B. Antil, L. Kumar, R. Ranjan, et al., ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 4 (2021) 3118-3129. DOI:10.1021/acsaem.0c02858 |

| [17] |

B. Ren, J. Miao, S. Wang, et al., Adv. Powder Technol. 32 (2021) 1774-1784. DOI:10.1016/j.apt.2021.03.035 |

| [18] |

L. Wu, X. Yang, T. Chen, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 427 (2022) 131773. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.131773 |

| [19] |

P. Kumar, E. Vahidzadeh, U.K. Thakur, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 5415-5436. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b00144 |

| [20] |

T. Wen, X. Wang, J. Wang, et al., Inorg. Chem. Front. 3 (2016) 1227-1235. DOI:10.1039/C6QI00091F |

| [21] |

Y. Zou, P. Wang, W. Yao, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 330 (2017) 573-584. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.135 |

| [22] |

L. Chen, Z. Bai, L. Zhu, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9 (2017) 32446-32451. DOI:10.1021/acsami.7b12396 |

| [23] |

P. Zhang, L. Wang, Z. Huang, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12 (2020) 15579-15587. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c00861 |

| [24] |

B. Hu, H. Wang, R. Liu, M. Qiu, Chemosphere 274 (2021) 129743. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129743 |

| [25] |

S. Liu, Z. Wang, Y. Lu, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 282 (2021) 119523. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119523 |

| [26] |

H.B. Zheng, W. Chen, H. Gao, et al., J. Mater. Chem. C 5 (2017) 10746-10753. DOI:10.1039/C7TC02966G |

| [27] |

V.W. Lau, M.B. Mesch, V. Duppel, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137 (2015) 1064-1072. DOI:10.1021/ja511802c |

| [28] |

H. Deng, X. Wang, L. Wang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 401 (2020) 125977. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125977 |

| [29] |

S. Kim, M. Hankel, W. Cha, et al., Nano Energy 72 (2020) 104702. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104702 |

| [30] |

Q. Meng, X. Yang, L. Wu, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 422 (2022) 126912. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126912 |

| [31] |

J. Xu, L. Zhang, R. Shi, Y. Zhu, J. Mater. Chem. A 1 (2013) 14766-14772. DOI:10.1039/c3ta13188b |

| [32] |

X. Li, J. Zhang, L. Shen, et al., Appl. Phys. A 94 (2008) 387-392. |

| [33] |

S.N. Talapaneni, G.P. Mane, D.H. Park, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 5 (2017) 18183-18192. DOI:10.1039/C7TA04041E |

| [34] |

J. Hu, P. Yang, C.M. Lieber, Phys. Rev. B 57 (1998) R3185-R3188. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.57.R3185 |

| [35] |

P. Chen, B. Lei, X. Dong, et al., ACS Nano 14 (2020) 15841-15852. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.0c07083 |

| [36] |

H. Yu, R. Shi, Y. Zhao, et al., Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1605148. DOI:10.1002/adma.201605148 |

| [37] |

Z. Mo, X. She, Y. Li, et al., RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 101552-101562. DOI:10.1039/C5RA19586A |

| [38] |

Q. Gu, Z. Gao, H. Zhao, et al., RSC Adv. 5 (2015) 49317-49325. DOI:10.1039/C5RA07284K |

| [39] |

P. Li, Y. Wang, J. Wang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 414 (2021) 128810. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.128810 |

| [40] |

Z. Huang, Z. Li, L. Zheng, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 328 (2017) 1066-1074. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.067 |

| [41] |

K. Li, M. Li, D. Xue, J. Phys. Chem. A 116 (2012) 4192-4198. DOI:10.1021/jp300603f |

| [42] |

J. Moens, G. Roos, P. Jaque, F. De Proft, P. Geerlings, Chemistry (Easton) 13 (2007) 9331-9343. DOI:10.1002/chem.200700547 |

| [43] |

H. Zhang, W. Liu, A. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 16110-16114. DOI:10.1002/anie.201909718 |

2022, Vol. 33

2022, Vol. 33