b School of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200241, China;

c College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Kunming University, Kunming 650214, China

The rapid and sensitive detection of pathogenic bacteria is crucial for ensuring food safety and public health, because pathogenic bacteria attract considerable attention in terms of food safety and can cause global threats to public health [1-3]. The standard plate colony counting method is time-consuming, and often takes several days owing to lengthy incubation periods [4]. Therefore, this strategy is inappropriate for the rapid and sensitive detection of pathogenic bacteria. Currently, detection methods for pathogenic bacteria include real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) [5], surface plasmon resonance imaging (SPRi) [6], enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [7], fluorescent assay [8], surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) [9], chemiluminescence (CL) techniques [10], and electrochemical biosensors [11]. These techniques have attracted considerable attention for use in bacterial detection. The advantages of these methods include high accuracy, decent selectivity, and short duration of analysis. However, these methods have certain shortcomings such as employing expensive instrumentation and enzymes, and involving intensive labour, labelling of signal molecules, and complex DNA extraction operations. Therefore, rapid and highly sensitive strategies must be urgently developed to detect pathogenic bacteria.

The microfluidic chip detection technology has received considerable attention owing to its ease of operation, high throughput, cost-effectiveness, and high sensitivity [12-17]. Compared with conventional strategies such as culture plating, ELISA, bioluminescence, and single/multiplex PCR, microchips have become attractive methods for the analysis of pathogenic bacteria. These powerful analytical methods have received considerable attention owing to their ease of operation, high throughput, cost-effectiveness, and high sensitivity. Since the development of microchip technology, some researchers have explored the possibility to use microchip capillary electrophoresis (MCE) for the detection of bacteria. MCE is a rapid analysis that requires low sample consumption while allowing automation of the process. Therefore, microchips have become an attractive strategy for the analysis of pathogenic bacteria, and are being recognised as promising alternative methods in this area [12-15]. The number of recent studies on the determination of pathogenic bacteria has been increasing. The determination of pathogenic bacteria has been reviewed with respect to electrochemical biosensors [18,19] and aptamer-based biosensors [20,21]. However, to the best of our knowledge, a systematic review of the microchip-based detection of pathogenic bacteria has not been reported. Therefore, this review aims at presenting a comprehensive overview of recent research (2015–2021) on microchips with a focus on the rapid identification of pathogenic bacteria. The different strategies, applications, limitations, and prospects of popular methods involving the use of microchips for detecting pathogenic bacteria are summarised herein.

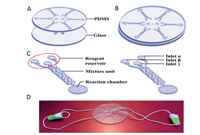

2. The detection of pathogenic bacteria based on microchips 2.1. Detection of pathogenic bacteria using aptamer combined with MCE 2.1.1. Using aptamer binding strategies combined with MCE for the detection of bacteriaAptamers, which are obtained by the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) technique, were first studied in the early 1990s based on their origin from a selection of DNA and RNA aptamers [22,23]. Aptamers have specific, defined structures and compact secondary or tertiary structures [22-25] based on which they exhibit a high affinity and decent selectivity towards specific targets such as small molecules [26], whole cells [27], proteins [28], and bacteria [29]. Aptamers have been recently used for bacterial recognition. Lee et al. described a strategy for the determination of E. coli using aptamer-functionalised single-walled carbon nanotube field-effect transistor arrays [30]. Luo et al. presented a method involving rapid and sensitive detection of E. coli based on an electrochemical biosensor using a target-induced aptamer displacement strategy [31]. Yuan et al. developed a simple detection method for S. typhimurium based on the use of aptamers as recognition and capture elements [32]. MCE has been recently used for the detection of bacteria using specific aptamers. Zhang et al. first described a new strategy for the detection of S. typhimurium using an MCE assay based on bacteria-specific aptamers [33]. The electrophoretic mobilities were found to be influenced by MCE owing to the different charge-to-mass ratios of the bacteria-aptamer complex and the free aptamers. MCE assisted in two peaks corresponding to the free aptamers and the bacteria-aptamer complex being obtained within 135 s. A schematic of this process is shown in Fig. 1. In addition, Zhang et al. described a rapid and sensitive MCE assay for the detection of E. coli using this strategy based on bacteria-specific aptamers [34].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Schematic of the application of a microchipelectrophoresis (MCE) assay based on bacteria-specific aptamers. MCE was employed to detect the bacteria-aptamer complex and the free aptamers. Reproduced with permission [33]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier. | |

Gan et al. developed a dual-mode aptasensor by combining colourimetry with a microfluidic chip for the simultaneous assay of different pathogenic bacteria in foods [35]. This dual-mode aptasensor offered certain advantages such as rapid on-site screening by the naked eye and simultaneous quantification of multiple bacteria. S. typhimurium and Vibrio parahaemolyticus (V. parahaemolyticus) were selected as the models in this study. First, the presence of the target pathogenic bacteria was examined by the naked eye. Subsequently, S. typhimurium and V. parahaemolyticus were simultaneously quantified using MCE. Fig. 2 shows the measurement scheme. In the experiment, a series of magnetic DNA-encoded probes were prepared via rolling circle amplification of a lengthy DNA chain (RCA-DNA) rich in G-quadruplex sequences. DNAzyme was subsequently obtained by combining DNA-encoded probes with hemin, which catalysed the 3, 3′, 5, 5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB)-H2O2 system for colour development. Meanwhile, the DNA-encoded probes were cleaved by EcoRV endonuclease, resulting in the production of DNA fragments of different lengths, which were separated by MCE; moreover, S. typhimurium and V. parahaemolyticus were simultaneously assessed by quantifying the fragments. This strategy was employed to obtain results, which were used to detect S. typhimurium and V. parahaemolyticus with detection limits of 32 CFU/mL and 30 CFU/mL, respectively.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (A) Schematic of the preparation of magnetic DNA-encoded probes. (B) Simultaneous determination of S.T and V.P using the dual-mode aptasensor. Reproduced with permission [35]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. | |

Catalysed hairpin assembly (CHA) is a nucleic-acid-based circle amplification method. As a toehold-mediated strand displacement reaction, CHA is driven by the free energy of base pair formation in the absence of enzymes [36]. Numerous DNA duplexes that have been produced via CHA have been combined with aptamers for isothermal sensing of biomolecules. The recent application of CHA in fluorescent [37] and electrochemical sensors [38] has attracted considerable interest. However, these strategies typically involve nucleic acid labelling, during which the performance of aptamers or hairpin probes can be weakened. Therefore, a new analytical method for CHA had to be developed. CHA-based MCE, as a new strategy, is extremely popular [36,39], and features an advantage in terms of being directly labelled with SYBR Gold in the MCE system; moreover, the original properties of the probes are not destroyed. Therefore, the recent use of CHA in combination with MCE has led to enhancements in the detection sensitivity [39]. Zhao et al. developed a method that was used as an aptamer and exonuclease-assisted signal amplification strategy for the detection of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) through MCE [40]. Gan et al. examined a combination of MCE and specific antibiotic aptamers and target-catalysed hairpins for the detection of two antibiotics, kanamycin and oxytetracycline [36]. CHA-based MCE, which was not studied for bacterial sensing, was first explored by Wang et al., who combined CHA with MCE to detect bacteria such as E. coli O157:H7 [39]. The strategy was developed using the E. coli O157:H7 aptamer (apt-E) for specific bacterial recognition in combination with aptamer-induced CHA. An illustration of this scheme is presented in Fig. 3. The strategy based on the combination of CHA and MCE is label-free, enzyme-free, cost-effective, and ultrasensitive. The method presented a limit of detection (LOD) as low as 75 CFU/mL. In addition, the detection of E. coli O157:H7 in defatted milk was achieved using this strategy. This research pioneered a new method based on CHA-based MCE for the detection of other bacteria in actual food samples.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Schematic of the detection of E. coli O157:H7 based on catalysed hairpin assembly (CHA) coupled with MCE. Reproduced with permission [39]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. | |

Wang et al. described a new strategy involving an aptamer-based probe and a novel universal primer-duplex polymerase chain reaction (UP-DPCR) process combined with the MCE method, which was applied for the simultaneous detection of S. typhimurium and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) [41]. The mechanism of bacterial detection is shown in Fig. 4. The recognition unit (aptamer) was used as the probe to specifically capture bacterial cells and subsequently release complementary DNAs (C1 and C2). Additionally, identical sequences were designed at both ends of the two DNA strands; therefore, the two released DNA strands (C1 and C2) were simultaneously amplified based on a pair of universal primers. The UP-DPCR products of C1 and C2 were detected by MCE, with the heights of the two peaks being related to the concentrations of the corresponding bacteria. The bacterial concentration was quantified based on the concentration of the corresponding complementary DNA. The results showed that sensitive detection of bacteria was achieved based on a combination of UP-DPCR and MCE, with LODs of 15 CFU/mL for S. typhimurium and 5 CFU/mL for P. aeruginosa. This strategy was successful in detecting S. typhimurium and P. aeruginosa in defatted milk. The complexity of the duplex PCR system was reduced using this strategy. The detection sensitivity of this method was improved in comparison with that of the simple aptamer recognition method [33] and the conventional genome-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based electrophoretic method [42].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Schematic of the detection of S. typhimurium and P. aeruginosa based on an aptamer-based probe and a combination of UP-DPCR and MCE. (A) Aptamers recognize the bacterial cells and release C1 and C2. (B) Detection of the released C1 and C2 via UP-DPCR and MCE-LIF. Reproduced with permission [41]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. | |

Probe-lengthening amplification (PLA) is a new nucleic-acid-amplification strategy that achieves decent selectivity by effectively avoiding nonspecific amplification. PLA has certain advantages such as a simple process of detection and an exponential accumulation of DNA copies. In addition, PLA has been employed for the detection of low-concentration DNA with a single-base differentiation ability [43]. Liu et al. described a PLA method involving an electrochemical biosensing strategy for ultrasensitive detection of genomic DNA in human serum [43]. The electrochemical signal was based on short probes for labelling with thiols and biotin; moreover, the operations were complex. Therefore, a new strategy was urgently required for the detection of nucleic acids based on PLA. A new strategy involving a combination of PLA and MCE was recently proposed [44]. This strategy exhibited sensitive detection of low-abundance genomic DNA; additionally, PLA was found to effectively avoid non-specific amplification. The target bacterial 16S rRNA gene was selected for this experiment. Meanwhile, auto-continuous MCE provided an ultra-high-throughput method for bacterial screening. Wang et al. proposed a strategy by combining PLA with MCE for the detection of five bacteria based on the analysis of 16S rRNA genes [44]. In this assay, four specific short probes were designed for a target bacterium by recognising the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. Fig. 5 shows a schematic of this method. The 16S rRNA genes of Enterococcus faecalis, E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), and Proteus mirabilis (P. mirabilis) were investigated using this approach. The results showed that sensitive detection of bacterial genes was realised based on the combination of PLA and MCE with a LOD of 30 fmol/L. This approach for the bacterial 16S rRNA gene has significant potential for application in the diagnosis of infection.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Schematic of probe-lengthening amplification for highly sensitivedetection of bacteria based on MCE. Reproduced with permission [44]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. | |

Among the recently developed nucleic acid assays for the detection of pathogenic bacteria, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has shown tremendous promise for the effective, simultaneous, quantitative, and rapid detection of pathogenic bacteria [45-48]. Although traditional methods of bacterial culture are simple and inexpensive, they are time-consuming [4,49]. Compared with traditional detection strategies, PCR-based techniques in combination with gel electrophoresis (GE) are being explored as alternative strategies for the detection of bacteria to reduce the detection time. However, gel electrophoresis exhibits low detection sensitivity and is tedious in terms of operation [50]. Therefore, combinations of PCR-based techniques and MCE are preferable for the detection of pathogenic bacteria, compared with those with GE, because of the obvious advantages of MCE such as rapid operation, easier miniaturisation, and higher accuracy in quantitative analysis of DNA fragments, as well as higher sensitivity and resolution [42,51,52]. Zhang et al. reported on the detection of three foodborne pathogenic bacteria (E. coli, S. aureus and S. Typhimurium) by MCE based on the PCR strategy. Primer pairs targeting these foodborne pathogenic bacteria were selected from the literature or using biosoft. The separation of these foodborne pathogenic bacteria PCR products was realised within 135 s with limits of 1.6–3.5 ng/µL. The LODs were as low as 62, 45 and 42 CFU/mL for S. aureus, E. coli and S. typhimurium, respectively [42]. Zhang et al. also reported a PCR-based strategy combined with MCE for the detection of three foodborne pathogenic bacteria (L. monocytogenes, E. coli, and S. typhimurium). The obtained LODs were as low as 68, 82 and 85 CFU/mL for L. monocytogenes, E. coli and S. typhimurium, respectively [53]. Zhu et al. employed PCR technology in combination with MCE to detect S. aureus, Proteus mirabilis and Enterobacter sakazakii (E. sakazakii) (Fig. 6) [54]. Li et al. developed a strategy for the rapid and specific detection of L. monocytogenes and Y. enterocolitica in food by combining MCE-laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) with duplex PCR [55]. Chen et al. described an approach involving MCE coupled with a simple-to-use space domain internal standard (SDIS) method for the rapid analysis of S. aureus [56]. Lee et al. investigated a novel paper-based capillary electrophoresis (pCE) microdevice that was fabricated by a mineral paper company. The microdevice was found to offer benefits in terms of being durable, waterproof, tear-resistant, simple to fabricate, lightweight, inexpensive, and disposable. The PCR products of E. coli O157:H7 and S. aureus were detected using the pCE microdevice. The LOD indicated that S. aureus and E. coli O157:H7 could be successfully analysed with 1.6 × 102 copies (0.5 pg) and 1.6 × 102 copies (0.5 pg) of the genomic DNA templates, respectively [57]. This highly sensitive MCE detection method requires smaller amounts of reagents and has a shorter analysis time. Therefore, PCR-based strategies combined with MCE can be employed for routine microbial detection in foods owing to these advantages.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. (A) Electropherogram of the DNA-500 kit with 1 to 19 peaks between the low-end internal standard (LM) and the high-end internal standard (UM). (B) The three PCR products correspond to: (1) E. sakazakii, (2) S. aureus, and (3) P. mirabilis. Reproduced with permission [54]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier. | |

PCR is considered the most powerful strategy for the detection of bacteria compared to traditional culture methods. However, a special PCR instrument had to be designed for amplification of target DNA or RNA in traditional PCR. Therefore, a new strategy was developed for performing PCR on a microchip. The advantages of performing PCR on a microchip, compared to traditional PCR, include high heat-transfer efficiency, excellent surface properties, cost-effective product design, and low reagent consumption. Rizzo et al. developed a rapid procedure for the molecular detection of P. aeruginosa, E. coli, S. epidermidis, and S. aureus by integrating pathogen capture in blood samples via peptides displayed in engineered M13 phage-coated paramagnetic beads with direct RT-PCR into microchips (Fig. 7) [58]. Tong et al. designed a fully portable and ultra-fast microchip-based PCR instrument as a rapid pathogen detection system. three functional components were incorporated into the designed instrument: electrical modules, heating, and an optical system. Two different real DNA samples, E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella, were evaluated using this portable PCR machine with a DNA detection sensitivity as low as 1 pg/µL [13]. Ohlsson et al. designed an integrated microsystem for the first online acoustophoretic plasma generation from blood with seed particle-enabled trapping enrichment and PCR to rapidly detect bacteria in blood samples. The entire process, including rapid separation, enrichment, and detection of bacteria from blood, was completed in less than 2 h The LOD of Pseudomonas putida (P. putida) was found to be as low as 1000 bacteria/mL in whole blood [59]. Gorgannezhad et al. fabricated a glass-polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-glass sandwiched microchip device as a microfluidic PCR array for the real-time PCR-based detection of E. coli and Bacteroidales. Modified Triton X-100 was employed on the surface of PDMS to prevent undesirable protein adsorption and enhance PCR compatibility in the chip. This strategy has been successfully applied to microbial faecal source tracking in water [60].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. A rapid procedure for the molecular detection of bacteria was prepared by the CDC-biochip. Reproduced with permission [58]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. | |

Molecular diagnostics play an important role in medical diagnosis, biological studies, food safety, and environmental monitoring. However, the effective detection of low amounts of target nucleic acids in complex biological samples required signal amplification techniques; loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) [61,62], CHA [39,63], RCA [64,65], and strand displacement amplification (SDA) [66,67], have been developed in this regard. SDA is an isothermal amplification method that generally depends on an ssDNA template containing complementary bases to the endonuclease recognition sequence; however, the SDA method falls short in terms of detecting short nucleic acids. Therefore, a new strategy involving the use of a defective T-junction structure was employed to support the SDA (dT-SDA). T junctions, which were used as a type of stable architecture, were formed by three strands of DNA based on the Watson-Crick complementary base pairing principle [68,69]. Yuan et al. developed an ultrasensitive and specific detection method for nucleic acids using a defective T junction combined with an electrochemical sensing strategy. The results indicated that the high sensitivity of target DNA for electrochemical DNA biosensing was as low as 0.4 fmol/L [70]. Wang et al. exploited this benefit of the dT-SDA strategy to develop a dT-SDA approach combined with MCE for the detection of longer bacterial 16S rDNA. A schematic of this process is shown in Fig. 8. With respect to dT-SDA, a primer and an auxiliary probe were designed to identify the target gene based on the formation of a stable defective T-junction structure via proximity hybridisation. Numerous ssDNA products were produced by triggering cascade SDA cycling based on the defective T junctions. The ssDNA products obtained were separated and detected using MCE. The concentration of the target gene was found to be a function of the quantity of ssDNA product. The proposed dT-SDA strategy took only up to 2.5 h to complete, and exhibited satisfactory sensitivity with a minimum LOD of 10 pmol/L; therefore, this method is a potential strategy for effective bacterial screening and infection diagnosis [71].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 8. Schematic of the detection of VP-16S rDNA based on the combination of a dT-SDA biosensor and MCE-LIF analysis. Reproduced with permission [71]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. | |

Among the recently developed nucleic acid assays for the detection of pathogenic bacteria, the isothermal strand-displacement polymerase reaction (ISDPR) technique has been explored as a promising strategy for effective, simultaneous, quantitative, and rapid detection of pathogenic bacteria [72,73]. ISDPR is an enzyme-assisted amplification process in which ssDNA is replaced by the substrate-ssDNA duplex through the extension of an initiator strand; moreover, this extension is completely complementary to the toehold region of the substrate strand. Nucleic acid amplification is achieved by this process based on the generation of several substrate-initiator duplexes. Sequence modelling is straightforward and temperature regulation is not strictly required in the process of ISDPR. In addition, ISDPR can realise exponential amplification with prominent signal amplification in less than an hour [74,75]. Based on these advantages, various assays based on molecular beacons [76], electrochemistry [77], and fluorescence [78] have been used to detect bacteria via ISDPR amplification. Wang et al. first integrated ISDPR with MCE for the detection of the characteristic mecA gene in methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [79]. Fig. 9 shows a schematic of the ISDPR signal recycling amplification in which the target DNA first binds to the hairpin probe (HP), which results in the DNA hairpin structure being opened. The target DNA is released by the primer hybridised with the probe in the presence of the Klenow fragment, exo-polymerase. Meanwhile, the released target DNA could open the next HP. Target recycling and amplification were thereby achieved. The amplified products of the HP-cDNA duplex were detected by MCE with a LOD of 12.3 pmol/L for the target DNA. The proposed strategy was successfully applied to detect methicillin-resistant S. aureus and could prove to be useful for detecting other bacteria owing to its rapid detection, ultrasensitivity, label-free ability, and straightforward operation.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 9. Schematic of mecA gene detection based on isothermal strand-displacement polymerase reaction (ISDPR) integrated with the MCE-LIF system. Reproduced with permission [79]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. | |

Sensitive, rapid, and cost-effective detection of pathogenic bacteria is urgently needed in medical diagnosis, biological studies, food safety, and environmental monitoring. Therefore, loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) has been employed for the rapid detection of pathogenic bacteria to accommodate the increasing demand for rapid detection techniques [80,81]. Compared with the PCR technology, LAMP is an isothermal nucleic-acid amplification method that does not require a thermal cycler because of the use of a single temperature throughout the reaction. In addition, LAMP is more tolerant to crude samples than PCR. Moreover, LAMP is more suitable than PCR because the PCR strategy requires well-equipped laboratories, sophisticated instruments, and specially trained technicians, which may not be feasible in resource-limited settings. LAMP has been used with four to six primers and a strand-displacing DNA polymerase to perform cyclic amplification at a constant temperature throughout the reaction. LAMP has also been proven to be more sensitive, specific, stable, and faster than PCR [82,83]. LAMP assays integrated with microchips have been recently developed for rapid pathogen detection. Zhou et al. fabricated a dual-sample microfluidic chip integrated with the LAMP assay to simultaneously detect ten pathogenic microorganisms. This on-chip LAMP provided highly sensitive results with LODs ranging from 10-1 pg/µL to 100 pg/µL for genomic DNA of tested bacteria, with run times of less than 30 min [80]. Wang et al. developed a versatile microfluidic chip platform integrated with LAMP for the simultaneous detection of S. pneumoniae and M. pneumonia. The platform used in this study was composed of a portable device and a polymer/paper microfluidic chip (Fig. 10). Magnetic particles were employed in the microfluidic chip to extract nucleic acids of pathogen genomic DNA. The DNA extraction was realised in ~15 min using this microfluidic chip. The genomic DNA of the pathogens was subjected to LAMP. A portable device was used to heat the microfluidic chip and record the results. The analytical sensitivity of the assay was as low as 2 fg for the target DNA [84]. Fu et al. developed a rapid on-chip gene quantification strategy based on LAMP-assisted PCR. The LAMP assays were employed to detect the target genes of E. coli and Enterococcus spp. using the most-probable-number approach. The colourimetric LAMP assay achieved a high sensitivity of as few as 4 copies/well and clear positive/negative observations on polymethyl methacrylate microchips [81]. Zhong et al. developed a microfluidic-based real-time fluorogenic LAMP system for the reliable and simple detection of Vibrio splendidus (V. splendidus). A LAMP primer set with six primers (arsB1) specifically targeting the arsB gene of V. splendidus was first designed in this study to test the portable microfluidic system. A linear standard curve for V. splendidus in a template concentration range of 5 × 103 to 5 × 106 CFU/mL was constructed [85]. Dou et al. fabricated a polymer/paper hybrid microfluidic biochip integrated with LAMP for the detection of three major types of meningitis-causing bacteria, S. pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), with high sensitivity and specificity. A smartphone camera under a portable UV light source was used to observe the results, which could also be observed by the naked eye. In addition, this strategy achieved high sensitivity with LODs of a few DNA copies per LAMP zone for the three investigated meningitis-causing bacteria within 1 h, without using any specialised laboratory instrument. Therefore, the microfluidic approach has significant potential for the detection of pathogens [86]. Seo et al. developed a centrifugal microfluidic device to identify foodborne pathogen bacteria via a combination of LAMP and colourimetric detection using Eriochrome Black T (EBT). The centrifugal microfluidic system included five identical structures to realise the genetic analysis of 25 pathogen samples in a high-throughput manner. The primer mixtures and DNA sample solutions were mixed in the microchannels, followed by being subjected to LAMP. Three types of pathogenic bacteria (Salmonella typhimurium, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus) were detected using the EBT-mediated colourimetric strategy. However, the results demonstrated that the genomic DNA of E. coli O157:H7 was specifically identified using primer sets in the LAMP reaction based on identification with the naked eye, with the entire process lasting 60 min. The developed microsystem enabled adequate testing of foodborne pathogens with high simplicity and high speed without using any bulky and expensive instrumentation [61].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 10. Schematics of the chip, portable device, and LAMP detection principle. (A) 3D illustration of the schematic of the chip. The IPµchip has three distinct functional domains. (a) DNA extraction region, (b) fluid control region, (c) the LAMP region. The pathogen's genomic DNA was extracted by magnetic beads method. A chromatographypaper disk is placed in each microchamber to preload LAMP primers. (B) 3D schematics of the portable device. (C) The schematic diagram of the LAMP detection principle. (B) 3D schematics of the portable device. (C) The schematic diagram of the LAMP detection principle. Reproduced with permission [84]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier B.V. | |

S. aureus is a Gram-positive rod-shaped bacterium found in air, dust, soil, and water that can cause various diseases in humans [87,88]. Rapid and accurate bacterial detection strategies that can effectively monitor the quality of food supplies are urgently required to enable effective control of microbial contamination of food and ensure food safety. Conventional microbial culture methods used for the identification and quantification of pathogens are time-consuming and extremely labour-intensive. Microchips are a powerful strategy to solve this issue because of their high information exportation, rapid response, automatic sampling, and high-throughput [89]. Zhang et al. developed a strategy that utilised Cy5 to label vancomycin (Cy5-Van) for the specific binding and detection of S. aureus, as shown in Fig. 11. The LOD of S. aureus obtained using this strategy was as low as 981 CFU/mL [89]. Song et al. developed a microfluidic platform for the detection of S. aureus based on fluorescence labelling. This microfluidic platform involved a microbial culture and S. aureus antibodies coated on the diameter of 50–90 µm microspheres to study the effect of capturing S. aureus. This platform quantitatively monitored bacteria with a LOD of 1.5 × 101 CFU/µL. The results indicated that the microfluidic chip used in this study was sensitive, accurate, portable, and could be further employed for investigating the detection of bacteria [90].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 11. Detection of S. aureus using fluorescently labelled vancomycin for specific binding based on MCE. Reproduced with permission [89]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier. | |

The rapid and sensitive detection of E. coli in water and food samples is extremely important for food safety. Several methods based on PCR [91] and electrochemical technologies [92] have been used for the detection of E. coli. One of these methods for the detection of E. coli involves measuring the activity of β-galactosidase (β-gal), which is frequently used as a marker for coliforms [93,94]. To date, β-gal has been used to examine the concentration of E. coli in food and water samples. Electrochemical methods [95], colourimetry [96], and fluorescent substrates [97] have been applied for the detection of E. coli based on the activity of β-gal. Wang et al. developed a sensitive strategy based on the activity of β-gal in which the measurement of 4-aminophenol was realised by MCE, which was used further to indicate E. coli. 4-Aminophenol is obtained via the hydrolysis of the 4-aminophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (PAPG) substrate by β-gal [98]. A schematic of the activity of β-gal activity is shown in Fig. 12. The concentration of E. coli was found to be proportional to the quantity of 4-aminophenol. This microfluidic platform used the field-amplified sample injection (FASI) method to increase the sensitivity of 4-aminophenol. The results indicated that the LOD reached 10 CFU/mL based on the fluorescence responses of 4-aminophenol, and this strategy achieved the detection of E. coli at a level as low as 23 CFU/mL in river water. Therefore, this strategy provided new insights into the detection of bacteria.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 12. Schematic of the detection of E. coli using an MCE assay for 4-aminophenol, which is obtained via hydrolysis of the 4-aminophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (PAPG) substrate by β-gal. Reproduced with permission [98]. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

MCE has become an attractive strategy for the analysis of pathogenic bacteria because of its ease of operation, high throughput, cost-effectiveness, and high sensitivity, compared with those of traditional culture or molecular methods such as PCR. However, currently reported MCE devices are facing significant challenges for the rapid detection of pathogenic bacteria. Therefore, various new microfluidic devices have been developed and applied for the detection of pathogens. Nguyen et al. developed a smartphone-based electric power system for microcapillary electrophoresis (µCE) on a chip (Fig. 13), which exhibits advantages such as improved portability of the µCE device and simple electrical operations. This system achieved the detection of 4.03 ng/µL of E. coli and 3.8 ng/µL of S. typhimurium [99]. Altintas et al. developed a fully automated microfluidic-based electrochemical biosensor for the quantification of E. coli in water samples (Fig. 14). This strategy was based on a nanomaterial-modified assay with high sensitivity and specificity, and exhibited tremendous potential for pathogen detection [100]. Fang et al. fabricated an integrated microfluidic chip (IMC) that included a membrane-based filtration module, a bacteria-capturing module, and a miniature PCR module for bacterial identification. This microdevice was applied for the rapid isolation of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria from blood. All white-blood cells and 99.5% of red blood cells were separated from the bacteria using a filtration module. The LOD for the PCR assay was 5 CFU per reaction, and the entire process was complete within 4 h [101]. Chen et al. developed a finger-actuated microfluidic chip (µFAchip) integrated with gel-based loop-mediated isothermal amplification (gLAMP) for the simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens. The designed µFAchip comprised three PDMS layers that could be used for finger-actuated operation to mix the sample and reagents in a controlled manner. An on-chip LAMP reaction was conducted on a miniaturised heater for realising point-of-care testing (POCT), and the resulting imaging was recorded using a portable fluorescence imaging system (Fig. 15). The developed µFAchip achieved a detection of as low as 1.6 cells with high selectivity and sensitivity, and provided a rapid and easy-to-operate platform for POCT-related applications of multiplexed pathogens [102]. Yamaguchi et al. developed a microfluidic device comprising on-chip fluorescent staining and semi-automated counting of target microbial cells based on fluorescent antibody staining. In addition, the microfluidic device was integrated with a self-made portable system for rapid and accurate counting of bacterial cells in freshwater [103]. Jin et al. developed a self-priming compartmentalisation (SPC) microdevice that was integrated into the LAMP system for enabling high-throughput visual detection. The microfluidic chip comprised a self-filling microwell array. The reaction solution was introduced from the access hole in the chip. In addition, the method employed for avoiding cross-contamination and ensuring the accuracy of the results was found to depend on the independent and closed wells. This approach achieved the simultaneous determination of six foodborne pathogens within 1 h [104]. Li et al. developed a strategy in which rapid bacterial identification in urine samples was achieved based on a microchannel silicon-nanowire microfluidic chip coupled with matrix assisted laser desorption ionisation-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Bacteria were detected at concentrations as low as 103 CFU/mL based on culturing urine samples for 4 h [105]. Khan et al. developed an electrically-receptive thermally-responsive (ER-TR) sensor chip that was composed of simple filter paper used as a substrate based on poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-graphene nanoplatelets. Au electrodes were evaporated to realise real-time capture of bacteria such as S. mutans, B. subtilis and E. coli [106]. Oh et al. developed a centrifugal microfluidic device for fully automated and colourimetric foodborne pathogen detection. DNA extraction and purification, DNA amplification and amplicon detection were performed on a single disc. Silica microbeads were used for the extraction and purification of bacterial genomic DNA from bacteria-contaminated milk samples. Four types of foodborne pathogens (S. typhimurium, E. coli O157:H7, L. monocytogenes and V. parahaemolyticus) were selected and subjected to LAMP to amplify specific genes of these bacteria. The results of the LAMP reactions relied on colourimetric detection mediated by a metal indicator. The results obtained indicated its potential for detecting foodborne pathogens from a contaminated milk sample, with a LOD of 10 bacterial cells achieved in 65 min [107]. Yang et al. developed a non-biofouling polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based microfluidic chip integrated with a functionalised nanoporous alumina membrane. The anti-E. coli O157:H7 antibody and anti-S. aureus antibody were individually immobilised on two nanoporous alumina membranes. E. coli O157:H7 and Staphylococcus aureus were specific targets in terms of bacterial detection, with a LOD of approximately 102 CFU/mL [108]. Shen et al. developed a herringbone microfluidic chip integrated with vancomycin-modified magnetic beads (herringbone-VMB microchip) to enrich pathogens, which were identified by MALDI-TOF MS [16]. Wang et al. achieved online and sensitive detection of Salmonella using a microfluidic biosensor that included immunomagnetic separation, fluorescence labelling, and smartphone video processing (Fig. 16). The LOD indicated that Salmonella could be successfully analysed at 58 CFU/mL using this proposed biosensor [109]. Li et al. developed a fully hand-powered centrifugal miniaturised nucleic-acid amplification testing platform, which comprised sample preparation, strand exchange amplification (SEA), and visual fluorescence detection as components. Sample preparation, reagent manipulation, mixing, SEA reaction, and fluorescence signal observations were realised in a single chip for the first time in this study. A schematic of the hand-powered microfluidic centrifugal platform is shown in Fig. 17. The microfluidic platform achieved a DNA or RNA LOD as low as 10 CFU/g via enrichment within 1 h [110]. Kwon et al. developed a modified herringbone microfluidic chip prepared using gold-nanoparticle-embedded PDMS. This microfluidic device was found to be applicable for adsorbing and destroying airborne bacteria and enriching and extracting DNA from pathogenic bacteria (S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa and Bacillus cereus) in air samples [111]. Kim et al. developed a micromachined microfluidic device that comprised cell focusing, dielectrophoretic sensing, and impedance measurement for label-free detection of E. coli in drinking water. The proposed system was found to achieve high throughput and exhibit a low LOD with enumerating populations as low as 300 CFU/mL [112].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 13. (A) Dimensions of the µCE chip fabricated using a CNC milling machine. (B) A high-boosting voltage DC-DC circuit system. (C) Schematic of the CE system. Reproduced with permission [99]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 14. (A) Illustration of custom-designed novel microfluidic-based electrochemical biosensor. (B) Pathogen detection assay. Reproduced with permission [100]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 15. Illustration of the designed µFAchip integrated with pathogen detection system. Reproduced with permission [102]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 16. Illustration of the principle of the proposed microfluidic biosensor integrated with fluorescent microscopic system. Reproduced with permission [109]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 17. Detection of V. parahaemolyticus using a hand-powered centrifugal microfluidic system. Reproduced with permission [110]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier. | |

This review provides an overview of recent advances in the development of microchip-based assays for the detection of pathogenic bacteria. Recent advances in microchip strategies have facilitated the fabrication of smaller, easy-to-use and fully integrated dual-mode aptasensors and aptamers featuring multiplex detection, PCR, LAMP, dT-SDA, ISDPR, or antibodies for the detection of pathogenic bacteria in a variety of biological samples [39,41,44,53,62,72]. However, several shortcomings and major challenges exist in terms of practical applications of these pathogenic bacteria assays.

For example, the sensitivity and selectivity of certain biological samples, such as food and serum, were found to be dependant on microfluidic devices. This necessitates the development of new microdevices for the detection of pathogenic bacteria. However, the newly designed microdevices require a complicated manufacturing process for fabrication, which increases the cost of detection [113]. Furthermore, the operation of these devices is complicated, which necessitates the development of new microchips that are suitable for testing complex samples. In terms of aptamer binding strategies, selective aptamers with specific properties face challenges in terms of their availability because non-specific binding of the aptamer with bacteria can lead to false positive results. A major challenge in the aptamer-induced CHA circle amplification and/or probe-lengthening amplification based on aptamers involves the selection of suitable aptamers to achieve an ideal result. This is because appropriate aptamers must be selected in terms of their dissociation constants and their stabilities and specificities [39]. Point-of-care devices are easy to integrate with smartphone-assisted detection for the analysis of pathogenic bacteria. However, these devices require significant optimisation for realising widespread commercialisation [102]. The urgent demand for the detection of pathogenic bacteria will positively stimulate research towards improved sensitivity and reproducibility as well as rapid, user-friendly operation. The detection of real-time PCR products and PCR products combined with MCE by these strategies presents obvious advantages. Compared with gel electrophoresis, smaller amounts of reagents, shorter analysis times, and automation of operation are achievable by MCE, which is cost-effective and therefore better suited for routine microbial analysis of foods [53]. During the measurement of β-galactosidase activity in combination with MCE, researchers should consider influencing factors such as the concentration of the buffer, derivatisation buffer pH, and derivatisation time. However, these factors limit the application of this strategy [98]. The use of antibodies in combination with MCE for the detection of bacteria involves high costs because of the expensive antibodies, which are also readily inactivated. The use of dT-SDA in combination with MCE for the detection of bacterial 16S rDNA consumes less time and has satisfactory sensitivity with high accuracy in real genomic sample analysis. This dT-SDA strategy is promising for diagnostic applications and biomedical research [71].

4. Future perspectivesIn summary, research on microfluidic devices for food and beverage safety-related applications has evolved considerably [114]. Despite the major challenges and application restrictions, new and exciting strategies based on microchips are being developed for the detection of pathogenic bacteria. Accordingly, MCE is expected to play an important role in the analysis of pathogenic bacteria in the near future for rapid, sensitive, and continuous on-site monitoring [115].

Microfluidic platforms have proven to be a successful method for the detection of pathogenic bacteria. These devices are time-effective, more sensitive, and more cost-effective than current traditional techniques used for the analysis of pathogenic bacteria. The use of MCE for the detection of pathogenic bacteria can be highly advantageous; it can introduce various benefits over other strategies. Further enhancements in currently employed strategies by combining with MCE are expected to broaden the scope for accommodating other applications. MCE provides selective and accurate detection results with high-performance devices at minimal cost, which enables the development of commercial microchip-based analytical strategies for pathogen detection. The urgent need for rapid pathogen detection will positively stimulate studies based on microchip stability and reproducibility as well as those on simple, user-friendly operation. Utilising the MCE strategy will certainly advance the current trends being researched for the detection of pathogenic bacteria.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21575042), Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2019M663577), Applied Basic Research Programs of Yunnan Science and Technology Department (No. 2018FH001–102), Talent Introduction Project of Kunming University (No. YJL18011) and Innovative Practical Scientific Research Project of Kunming University (No. HXHG1805).

| [1] |

J.H. Jung, G.Y. Kim, T.S. Seo, Lab Chip 11 (2011) 3465-3470. DOI:10.1039/c1lc20350a |

| [2] |

L. Liu, J. Liu, H. Huang, et al., Microchem. J. 148 (2019) 702-707. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2019.05.016 |

| [3] |

D. Li, L. Liu, Q. Huang, et al., World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37 (2021) 45. DOI:10.1007/s11274-021-03002-9 |

| [4] |

E. Voitoux, V. Lafarge, C. Collette, B. Lombard, Int. J. Food Microbiol. 77 (2002) 213-221. DOI:10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00110-1 |

| [5] |

C.L. Lee, D.S.W. Ow, S.K.W. Oh, J. Microbiol. Methods 65 (2006) 258-267. DOI:10.1016/j.mimet.2005.07.019 |

| [6] |

E. Bulard, A. Bouchet-Spinelli, P. Chaud, et al., Anal. Chem. 87 (2015) 1804-1811. DOI:10.1021/ac5037704 |

| [7] |

T. Chang, S. Huang, J. Food Prot. 57 (1994) 184-189. DOI:10.4315/0362-028X-57.3.184 |

| [8] |

L. Xu, Z. Lu, L. Cao, et al., Food Control 75 (2017) 21-28. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.12.018 |

| [9] |

E. Yang, D. Li, P. Yin, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 172 (2021) 112758. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2020.112758 |

| [10] |

Y. Zhag, C. Tan, R. Fei, et al., Anal. Chem. 86 (2014) 1115-1122. DOI:10.1021/ac4028774 |

| [11] |

H. Yu, W. Guo, X. Lu, et al., Food Control 127 (2021) 108117. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108117 |

| [12] |

M.G. Rizzo, S. Carnazza, L.M. De Plano, et al., Sens. Actuators B 329 (2021) 129227. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2020.129227 |

| [13] |

R. Tong, L. Zhang, Q. Song, et al., Electrophoresis 40 (2019) 1699-1707. DOI:10.1002/elps.201900090 |

| [14] |

Y. Zhang, X. Hu, Q. Wang, Talanta 232 (2021) 122410. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2021.122410 |

| [15] |

F. Luo, Y. Lu, X. Geng, et al., Anal. Chem. 93 (2021) 3551-3558. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04991 |

| [16] |

Y. Shen, J. Yi, M. Song, et al., Analyst 146 (2021) 4146-4153. DOI:10.1039/D1AN00335F |

| [17] |

N. Zhuang, J. Ma, L. Yang, et al., Microchem. J. 164 (2021) 106075. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2021.106075 |

| [18] |

H.O. Kaya, A.E. Cetin, M. Azimzadeh, S.N. Topkaya, J. Electroanal. Chem. 882 (2021) 114989. DOI:10.1016/j.jelechem.2021.114989 |

| [19] |

R. Pourakbari, N. Shadjou, H. Yousefi, et al., Microchim. Acta 186 (2019) 820. DOI:10.1007/s00604-019-3966-8 |

| [20] |

M. Shahdordizadeh, S.M. Taghdisi, N. Ansari, et al., Sens. Actuators B 241 (2017) 619-635. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2016.10.088 |

| [21] |

M. Majdinasab, A. Hayat, J.L. Marty, TrAC Trends in Anal. Chem. 107 (2018) 60-77. DOI:10.1016/j.trac.2018.07.016 |

| [22] |

A.D. Ellington, J.W. Szostak, Nature 355 (1992) 850-852. DOI:10.1038/355850a0 |

| [23] |

C. Tuerk, L. Gold, Science 249 (1990) 505-510. DOI:10.1126/science.2200121 |

| [24] |

X. Wang, D. Yan, Microchem. J. 165 (2021) 106099. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2021.106099 |

| [25] |

X. Zhang, Y. Wang, H. Deng, et al., Microchem. J. 161 (2021) 105761. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2020.105761 |

| [26] |

M. Zayats, Y. Huang, R. Gill, C.A. Ma, I. Willner, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (2006) 13666-13667. DOI:10.1021/ja0651456 |

| [27] |

S. Fukuyama, S. Kumamoto, S. Nagano, et al., Talanta 228 (2021) 122239. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2021.122239 |

| [28] |

A. Numnuam, K.Y. Chumbimuni-Torres, Y. Xiang, et al., Anal. Chem. 80 (2008) 707-712. DOI:10.1021/ac701910r |

| [29] |

W. Gao, B. Li, R. Yao, et al., Anal. Chem. 89 (2017) 9836-9842. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01813 |

| [30] |

H.M. So, D.W. Park, E.K. Jeon, et al., Small 4 (2008) 197-201. DOI:10.1002/smll.200700664 |

| [31] |

C. Luo, Y. Lei, L. Yan, et al., Electroanalysis 24 (2012) 1186-1191. DOI:10.1002/elan.201100700 |

| [32] |

J. Yuan, Z. Tao, Y. Yu, et al., Food Control 37 (2014) 188-192. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.09.046 |

| [33] |

Y. Zhang, F. Luo, Y. Zhang, et al., J. Chromatogr. A 1534 (2018) 188-194. DOI:10.1016/j.chroma.2017.12.054 |

| [34] |

Y. Zhang, L. Zhu, P. He, et al., Talanta 197 (2019) 284-290. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2019.01.040 |

| [35] |

J. Yu, H. Wu, L. He, et al., Talanta 225 (2021) 122062. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2020.122062 |

| [36] |

Y. Wang, N. Gan, Y. Zhou, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 97 (2017) 100-106. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2017.05.017 |

| [37] |

J. Li, Y. Xiang, L. Zhang, et al., Sens. Actuators B 288 (2019) 757-762. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2019.03.058 |

| [38] |

S. Wang, S. Lu, J. Zhao, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 126 (2019) 565-571. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2018.09.088 |

| [39] |

F. Luo, Z. Li, G. Dai, et al., Sens. Actuators B 306 (2020) 127577. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2019.127577 |

| [40] |

Y. Qin, L. Zhang, S. Li, et al., Chem. Commun. 53 (2017) 455-458. DOI:10.1039/C6CC08911A |

| [41] |

F. Luo, Z. Li, G. Dai, et al., J. Chromatogr. A 1615 (2020) 460734. DOI:10.1016/j.chroma.2019.460734 |

| [42] |

Y. Zhang, L. Zhu, Y. Zhang, P. He, Q. Wang, J. Chromatogr. A 1555 (2018) 100-105. DOI:10.1016/j.chroma.2018.04.058 |

| [43] |

J.Y. Chen, Z.J. Liu, X.W. Wang, et al., Anal. Chem. 91 (2019) 4552-4558. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05692 |

| [44] |

F. Luo, Y. Lu, Z. Li, et al., Sens. Actuators B 325 (2020) 128784. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2020.128784 |

| [45] |

J. Xu, P. Zhang, L. Zhuang, et al., J. Food Saf. 39 (2019) 12674. |

| [46] |

M. Aslam, J. Hogan, K.L. Smith, Food Microbiol 20 (2003) 345-350. DOI:10.1016/S0740-0020(02)00121-1 |

| [47] |

D. Zeng, S. Chen, L. Jiang, et al., Microchem. J. 159 (2020) 105418. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2020.105418 |

| [48] |

D. Zeng, B. Qian, K. Zhao, et al., Microchem. J. 156 (2020) 104940. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2020.104940 |

| [49] |

J.L. McKillip, L.A. Jaykus, M.A. Drake, J. Appl. Microbiol. 89 (2000) 49-55. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01079.x |

| [50] |

L. De Vero, E. Gala, M. Gullo, et al., Food Microbiol 23 (2006) 809-813. DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2006.01.006 |

| [51] |

X. Jiang, N. Shao, W. Jing, et al., Talanta 122 (2014) 246-250. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2014.01.053 |

| [52] |

Y. Li, Y. Li, B. Zheng, L. Qu, C. Li, Anal. Chim. Acta 643 (2009) 100-107. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2009.04.006 |

| [53] |

Z. Yan, X. Hu, Q. Wang, Microchem. J. 157 (2020) 104876. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2020.104876 |

| [54] |

L. Zhu, Y. Zhang, P. He, Y. Zhang, Q. Wang, J. Chromatogr. B: Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 1093 (2018) 141-146. |

| [55] |

Y. Li, H. Su, Y. Lan, J. AOAC Int. 101 (2018) 1833-1838. DOI:10.5740/jaoacint.17-0507 |

| [56] |

J. Chen, Y. Sun, X. Peng, et al., Sensors 21 (2021) 1334. DOI:10.3390/s21041334 |

| [57] |

J.W. Lee, D. Lee, Y.T. Kim, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 91 (2017) 388-392. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2016.12.053 |

| [58] |

M.G. Rizzo, S. Carnazza, L.M. De Plano, et al., Sens. Actuators B 329 (2021) 129227. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2020.129227 |

| [59] |

P. Ohlsson, M. Evander, K. Petersson, et al., Anal. Chem. 88 (2016) 9403-9411. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00323 |

| [60] |

L. Gorgannezhad, K.R. Sreejith, J. Zhang, et al., Micromachines (Basel) 10 (2019) 883. DOI:10.3390/mi10120883 |

| [61] |

S.J. Oh, B.H. Park, J.H. Jung, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 75 (2016) 293-300. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2015.08.052 |

| [62] |

Y. Fu, X. Zhou, X. Duan, et al., Sens. Actuators B 321 (2020) 128502. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2020.128502 |

| [63] |

L. Zou, X. Li, J. Zhang, L. Ling, Anal. Chem. 92 (2020) 12656-12662. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02858 |

| [64] |

T. Zhang, Q. Tao, X.J. Bian, Q. Chen, J. Yan, Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 49 (2021) 377-386. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2040(21)60085-3 |

| [65] |

Y. He, L. Cheng, Y. Yang, et al., Sens. Actuators B 320 (2020) 128407. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2020.128407 |

| [66] |

R. Cai, F. Yin, H. Chen, Y. Tian, N. Zhou, Microchim. Acta 187 (2020) 304. DOI:10.1007/s00604-020-04293-9 |

| [67] |

T. Wang, Q. Peng, B. Guo, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 150 (2020) 111954. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2019.111954 |

| [68] |

J. Cui, H. Han, J. Piao, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12 (2020) 34130-34136. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c06032 |

| [69] |

K. Fan, R. Yang, Y. Zhao, et al., Sens. Actuators B 321 (2020) 128515. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2020.128515 |

| [70] |

R. Yuan, S. Ding, Y. Yan, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 77 (2016) 19-25. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2015.09.009 |

| [71] |

F. Luo, Y. Lu, X. Geng, et al., Anal. Chem. 93 (2021) 3551-3558. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04991 |

| [72] |

Y. Peng, S. Wu, Z. Sun, et al., Sens. Actuators B 313 (2020) 128046. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2020.128046 |

| [73] |

Y. Dai, A. Furst, C.C. Liu, Trends Biotechnol 37 (2019) 1367-1382. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.10.001 |

| [74] |

A.M. Solovjev, S.A. Kurzeev, I.Y. Sakharov, Talanta 215 (2020) 120895. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2020.120895 |

| [75] |

O. Mayboroda, I. Katakis, C.K. O'Sullivan, Anal. Biochem. 545 (2018) 20-30. DOI:10.1016/j.ab.2018.01.005 |

| [76] |

H. Dong, J. Zhang, H. Ju, et al., Anal. Chem. 84 (2012) 4587-4593. DOI:10.1021/ac300721u |

| [77] |

T. Wang, Z. Zhang, Y. Li, G. Xie, Sens. Actuators B 221 (2015) 148-154. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2015.06.057 |

| [78] |

X. Yan, M. Tang, J. Yang, et al., RSC Adv 8 (2018) 31710-31716. DOI:10.1039/C8RA06480F |

| [79] |

Y. Lu, F. Luo, Z. Li, G. Dai, et al., Talanta 222 (2021) 121686. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121686 |

| [80] |

Q.J. Zhou, J.F. Lu, X.R. Su, et al., J. Fish Dis. 44 (2021) 401-413. DOI:10.1111/jfd.13325 |

| [81] |

J. Fu, E.L.C. Chiang, C.A.D. Medriano, L. Li, S. Bae, Water Res. 199 (2021) 117172. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2021.117172 |

| [82] |

Y.P. Wong, S. Othman, Y.L. Lau, S. Radu, H.Y. Chee, J. Appl. Microbiol. 124 (2018) 626-643. DOI:10.1111/jam.13647 |

| [83] |

S. Lee, V.S.L. Khoo, C.A.D. Medriano, et al., Water Res. 160 (2019) 371-379. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2019.05.049 |

| [84] |

H. Wang, Z. Ma, J. Qin, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 126 (2019) 373-380. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2018.11.011 |

| [85] |

R. Zhong, S. Liu, X. Wang, et al., Anal. Methods 12 (2020) 2985-2994. DOI:10.1039/D0AY00566E |

| [86] |

M. Dou, S.T. Sanjay, D.C. Dominguez, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 87 (2017) 865-873. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2016.09.033 |

| [87] |

A.L.H. Gray, A. Antevska, D.S. Oluwatoba, et al., Anal. Chem. 92 (2020) 11802-11808. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.0c01974 |

| [88] |

W. Kong, J. Xiong, H. Yue, Z. Fu, Anal. Chem. 87 (2015) 9864-9868. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02301 |

| [89] |

Y. Zhang, Y. Zhang, Y. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 29 (2018) 1383-1386. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.10.026 |

| [90] |

B. Song, J. Wang, Z. Yan, et al., Bioengineered 11 (2020) 1137-1145. DOI:10.1080/21655979.2020.1831362 |

| [91] |

A. Garrido-Maestu, S. Azinheiro, J. Carvalho, P. Fuciños, M. Prado, Food Control 108 (2020) 106790. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106790 |

| [92] |

X. Zhang, T. Wu, Y. Yang, et al., Sens. Actuators B 321 (2020) 128472. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2020.128472 |

| [93] |

C. Sicard, N. Shek, D. White, et al., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 406 (2014) 5395-5403. DOI:10.1007/s00216-014-7935-0 |

| [94] |

E.W. Rice, M.J. Allen, S.C. Edberg, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56 (1990) 1203-1205. DOI:10.1128/aem.56.5.1203-1205.1990 |

| [95] |

L.V. Tarditto, M.A. Zon, H.G. Ovando, et al., Talanta 174 (2017) 507-513. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2017.06.059 |

| [96] |

J. Chen, A.A. Jackson, V.M. Rotello, S.R. Nugen, Small 12 (2016) 2469-2475. DOI:10.1002/smll.201503682 |

| [97] |

H. Labrousse, J.L. Guesdon, J. Ragimbeau, S. Avrameas, J. Immunol. Methods 48 (1982) 133-147. DOI:10.1016/0022-1759(82)90188-0 |

| [98] |

Y. Zhang, Y. Zhang, L. Zhu, P. He, Q. Wang, Anal. Methods 11 (2019) 1558-1565. DOI:10.1039/C9AY00067D |

| [99] |

N. Van Dan, N. Hau Van, K.H. Bui, T.S. Seo, Sens. Actuators B 301 (2019) 127108. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2019.127108 |

| [100] |

Z. Altintas, M. Akgun, G. Kokturk, Y. Uludag, Biosens. Bioelectron. 100 (2018) 541-548. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2017.09.046 |

| [101] |

Y.L. Fang, C.H. Wang, Y.S. Chen, et al., Lab Chip 21 (2021) 113-121. DOI:10.1039/D0LC00966K |

| [102] |

P. Chen, C. Chen, H. Su, et al., Talanta 224 (2021) 121844. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121844 |

| [103] |

N. Yamaguchi, Y. Fujii, Biol. Pharm. Bull. 43 (2020) 87-92. DOI:10.1248/bpb.b19-00549 |

| [104] |

Z. Jin, G. Ding, G. Li, et al., J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 95 (2020) 1460-1466. DOI:10.1002/jctb.6331 |

| [105] |

Y. Li, T. Wang, J. Wu, Analyst 146 (2021) 1151. DOI:10.1039/D0AN02222E |

| [106] |

M.S. Khan, S.K. Misra, K. Dighe, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 110 (2018) 132-140. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2018.03.044 |

| [107] |

S.J. Oh, B.H. Park, G. Choi, et al., Lab Chip 16 (2016) 1917-1926. DOI:10.1039/C6LC00326E |

| [108] |

F. Tian, J. Lyu, J. Shi, F. Tan, M. Yang, Sens. Actuators B 225 (2016) 312-318. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2015.11.059 |

| [109] |

S. Wang, L. Zheng, G. Cai, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 140 (2019) 111333. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2019.111333 |

| [110] |

M. Li, A. Ge, M. Liu, et al., Talanta 219 (2020) 121221. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121221 |

| [111] |

K. Kwon, J.W. Park, K.A. Hyun, et al., Sens. Actuators B 248 (2017) 580-588. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2017.04.043 |

| [112] |

M. Kim, T. Jung, Y. Kim, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 74 (2015) 1011-1015. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2015.07.059 |

| [113] |

S. Mao, X. Hu, Y. Tanaka, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. (2021). DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.065 |

| [114] |

Y. Wu, L. Zhao, Y. Chang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 3446-3449. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.05.034 |

| [115] |

W. Hu, D. Gao, Z. Su, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. (2021). DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.041 |

2022, Vol. 33

2022, Vol. 33