On the basis of extensive reports, we realized that reactive oxygen species (ROS) actively participate in a variety of biological processes, and hypochlorous acid (HClO) is an important component of ROS; specifically, HClO is produced by immune cells to fight infections [1-3]. When bacteria invade the human body or when the epidermis is damaged, endogenous HClO is secreted from neutrophils in leukocytes in the body to resist these foreign bacteria and viruses by destroying their cell walls and making them unable to survive [4-8]. It is known that chlorine is commonly used to sterilize tap water. The sterilization effect is achieved because the formed HClO in an aqueous solution is a strong oxidant that kills harmful substances such as bacteria. Thus, residual amounts of HClO in tap water are usually present. In addition, HClO discolors dyes and organic colors; thus, it is commonly used in industrial production or in daily life as a bleach, antioxidant, deodorant and disinfectant. However, excessive amounts of HClO are of great harm to the organism's health and result in tissue necrosis and diseases such as atherosclerosis and cancer [9-11].

For the qualitative and quantitative analysis of HClO, many scientific methods have been invented, including mass spectrometry, HPLC analysis and bioanalytical methods etc. [12-14]. When implementing these methods of operation, the process is complicated, time-consuming and labor-intensive, and the equipment is difficult to master. To avoid the shortcomings, chemical sensors (e.g., fluorescence probes) that are designed to detect HClO are essential. It is known that fluorescence probes possess many advantages over the above methods, including high selectivity, sensitivity, and ease of operation. In addition, fluorescent probes provide strategies for detecting HClO in vitro and in vivo [15-21].

Thus far, scientists have developed many fluorescence probes to detect HClO [22-31]. Strong oxidation of HClO is a key consideration in the synthesis of these sensors [32-35]. However, some of the developed probes do not perform well in a physiological pH range and require excessive amounts of organic solvents. A fluorescent probe with a single emission peak response to HClO does not perform well and is susceptible to environmental factors like the concentration of fluorescent probe, excitation intensity and so on [36-41]. Therefore, there is a pressing need to overcome these issues by creating new ratiometric fluorescence probes. By measuring the intensity changes of two emission peaks, ratiometric fluorescence probes tend to perform well in quantitative detection and offer more accurate data. In addition, successful application in living cells detection and some other useful practical applications can make fluorescence probes more attractive.

In this study, a new ratiometric benzothiazole-based fluorescent probe (HBT-HBZ) is reported. The developed probe exhibits excellent selectivity for HClO compared with other analytes. HBTHBZ uses 3-(benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-2-hydroxy-5-methylbenzaldehyde as a donor. When HBT-HBZ is dissolved in a phosphatebuffered saline (PBS) solution, it exhibited weak orange fluorescence after the addition of some HClO into the solution; an intramolecular cyclization reaction immediately occurred between HBT-HBZ and HClO, and unbridged C=N transformed into bridged C=N [42]. The fluorescence of the mixture exhibited a strong cyan color. From this phenomenon, we concluded that HBTHBZ can selectively identify HClO among other ions (e.g., ROS and RNS) in the PBS solution. Most importantly, HBT-HBZ provides an efficient approach for analyzing HClO residues in tap water. Finally, HBT-HBZ was used to image HClO in HeLa cells.

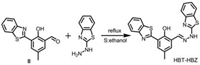

3-(Benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-2-hydroxy-5-methylbenzaldehyde (Ⅱ) was synthesized according to our previous report [43]. The synthetic routes of HBT-HBZ are illustrated in Scheme 1. A Schiff base reaction occurred between compound Ⅱ and 2- hydrazino benzothiazole to form HBT-HBZ. Specific synthesis and characterization are located in Supporting information (Scheme S1, Figs. S1–S9).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Synthetic route for HBT-HBZ. | |

A series of experiments of the HBT-HBZ response to ROS, RNS and other ions, (e.g., ClO-, ONOO-, tBuOO·, ROO·, ClO4-, HPO42-, H2O2, CO32-, HSO3-, SO42-, NO2-, NO3-, SCN-, S2-, Cl-, Br- and I-), in the PBS solution (50 mmol/L, pH 7.4) were performed via fluorescence and UV spectroscopy to explore the selectivity of HBTHBZ for HClO. The HBT-HBZ solution showed an orange fluorescence band at 572 nm; after the addition of HClO (100 μmol/L), the fluorescence intensity considerably increased at 470 nm and decreased at 572 nm. However, there was no major change in the fluorescence of the solution after the addition of other analytes (Fig. S10]in Supporting information). The fluorescence intensity ratio between 470 nm and 572 nm after the addition of different analytes is shown in Fig. 1A. In addition, HBTHBZ can clearly distinguish HClO and other analytes by UV spectroscopy (Fig. 1B); specifically, the absorbance of the solution clearly decreased in the range of 270–400 nm after adding HClO; other analytes did not show a similar decrease.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (A) Fluorescence intensity ratio (I470 nm/I572 nm) changes of HBT-HBZ (10 μmol/L) with different analytes (100 μmol/L) in the PBS solution (50 mmol/L, pH 7.4) (λex = 400 nm. Slit: 5 nm/10 nm): 1. HBT-HBZ, 2. ClO-, 3. ONOO-, 4. tBuOO·, 5. ROO·, 6. ClO4-, 7. HPO42-, 8. H2O2, 9. CO32-, 10. HSO3-, 11. SO42-, 12. NO2-, 13. NO3-, 14. SCN-, 15. S2-, 16. Cl-, 17. Br-, 18. I-. (B) Absorption spectra of HBT-HBZ (10 μmol/L) with ClO- (100 μmol/L) and other anions (100 μmol/L) in the PBS (50 mmol/L, pH 7.4) solution. (C) Fluorescence titration spectra of HBT-HBZ (10 μ mol/L) with increasing HClO concentration (λex = 400 nm. Slit: 5 nm/10 nm). Inset: Fluorescence color of HBTHBZ (10 μmol/L) (left), fluorescence color of HBT-HBZ with 10 equiv. of HClO (right) under a portable 365 nm UV lamp. (D) Linear relationship between fluorescent intensity ratios (I470 nm/I572 nm) and HClO concentrations (λex = 400 nm. Slit: 5 nm/10 nm). | |

Then, fluorescence titration experiments were conducted to determine the sensitivity of HBT-HBZ for HClO. With the addition of HClO, a new peak appeared at 470 nm, and its intensity gradually increased, whereas the intensity of emission at 572 nm slightly decreased. HClO can be visually identified under a portable 365 nm UV lamp; after adding HClO, the fluorescence color changed from orange to cyan (Fig. 1C). The ratios of fluorescence intensity (I470 nm/I572 nm) were mapped as a function of the HClO amount (0–10 equiv.), and a linear relationship was observed (Fig. 1D). From the linear curve, 24 nmol/L detection limit was obtained using a well-knownformula (Formula S1 in Supporting information).Based onformula S2 (Supporting information), the quantumyieldsof HBTHBZ increased from 0.26 to 0.34 after the addition of HClO (10 equiv.).

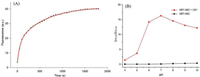

We further explored the time effects of HBT-HBZ fluorescence with 10 equiv. HClO in the PBS solution (50 mmol/L, pH 7.4). When HClO was added into the solutions in which HBT-HBZ was dissolved, an immediate fluorescence at 470 nm was observed; fluorescence intensity increased for approximately 1200 s and then remained stable (Fig. 2A). To investigate the appropriate pH range for HClO sensing, a series of pH-dependent experiments was performed. In the pH range of 4–10, the ratio of fluorescence intensity (I470 nm/I572 nm) of HBT-HBZ is very low and is approximately equal to zero. After adding 10 equiv. of HClO, the ratios showed considerable changes in the pH range of 5 to 10, which indicated that the probe was suitable for use under physiological conditions (Fig. 2B).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (A) Time-spectrum of fluorescence at 470 nm of HBTHEZ (10 μmol/L) in the PBS solution (50 mmol/L, pH 7.4) afer the addition of HCIO (λex=400 nm.Slit:5nm/10nm). (B) Changes in the fluorescence intensity ratios (I470 nm/I572 nm) before and after the addition of HCIO (100 u mol/L) to HBTHRZ (10 μmol/L) at different pH in the PBS solution (50 mmol/L, pH 7.4) (λex = 400 nm. Slit: 5 nm/10 nm). | |

Then, we carefully studied the mechanism of HClO detection by HBT-HBZ. First, we compared the changes in the 1H NMR spectra with and without the addition of NaClO to the HBT-HBZ solution. With the addition of NaClO, the deprotonation of hydroxyl group is occurred, and two proton signals at δ 12.66 (imine) and δ 12.34 (amine) disappeared (Fig. S11 in Supporting information), which indicated that the oxidation of HBT-HBZ by HClO occurs on the imine group that was oxidized into a triazolyl group; this was also confirmed by mass spectrometry measurements of the addition of HClO to HBTHBZ (Fig. S12 in Supporting information). The mechanism of HBT-HBZ detection of HClO is shown in Scheme 2 and Scheme S2 (Supporting information). However, three infrared peaks at 2850, 2912, 2960 nm appeared after the addition of NaClO, which also confirmed that the imine group was oxidized into a triazolyl group (Fig. S14 in Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Mechanism of the recognition process. | |

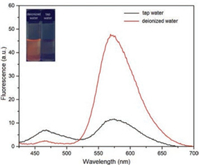

To evaluate its practical applications in industrial production and daily life, HBTHBZ was used to sense HClO in tap water. Although fluorescent probes for detecting HClO have many practical applications, they are rarely used for detecting HClO in tap water. On the basis of the abovementioned, we developed a method for determining the concentration of HClO in tap water. After adding 2970 μL of deionized water and tap water to two quartz cuvettes, 30 μL of HBT-HBZ (1 mmol/L) was added into quartz cuvettes and stirred. Then, we collected the fluorescence spectra and visually observed solution fluorescence with a portable UV lamp. Different from deionized water, the emission peak of the fluorescence spectrum at 572 nm considerably decreased after HBT-HBZ was added to tap water, whereas the fluorescence intensity at 470 nm increased. The insert in Fig. 3 shows that fluorescence of deionized water and tap water with HBT-HBZ are completely different under a portable 365 nm UV lamp (Fig. 3). From the abovementioned linear relationship, it was determined that HBT-HBZ was sensitive toward HClO in the tap water sample and HClO concentration was calculated as 2.0 × 10-5 mol/L, which is higher than the required standard concentrations (8.4 × 10-6 mol/L) [44, 45]. According to GB 5749-2006, tap water in our laboratory is in compliance with the regulations [46]. Thus, we determined that HBTHBZ has a practical application in quantitatively determining the concentration of HClO in an environmental sample.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Fluorescence spectra of HBT-HBZ (10 μmol/L) in deionized water and tap water (2970 μL) (λex = 400 nm. Slit: 5 nm/10 nm). Inset: Fluorescence color of HBT-HBZ (10 μmol/L) in deionized water and tap water under a portable 365 nm UV lamp. | |

Inspired by the sensing properties of the extra-receptor HBT-HBZ, we explored the detection of HClO by HBT-HBZ imaging in cells. When HeLa cells were treated with HBT-HBZ (10 μmol/L), they showed yellow fluorescence. After the treatment with NaClO (100 μmol/L), different color of a bright cyan fluorescence was observed in HeLa cells (Fig. 4). The abovementioned experimental results showed that HBT-HBZ had another practical application in biological systems.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Fluorescence images. (A–C) HeLa cells incubated with HBT-HBZ (10 μmol/L) for 15 min at 37 ℃. (D–F) HeLa cells treated with HBT-HBZ (10 μmol/L) before and after incubation with HClO (100 μmol/L) for another 15 min at 37 ℃. | |

In conclusion, we developed a new type of ratiometric fluorescence probe (HBTHBZ), which is based on benzothiazole for the selective and sensitive discrimination of HClO in aqueous solutions. The probe exhibited high selectivity for HClO among other ROS, RNS and anions. The detecting mechanism was confirmed by MS, 1H NMR and FT-IR analyses. In addition, HBT-HBZ has some practical applications such as the analysis of the HClO content in tap water. Furthermore, confocal fluorescence microscopy imaging showed that HBT-HBZ can be applied for detecting HClO in living cells.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFA0902200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21722605, 21978131 and 21878156), the Six Talent Peaks Project in Jiangsu Province (No. XCL-034) and the Project of Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions(PAPD).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.03.064.

| [1] |

X. Chen, F. Wang, J.Y. Hyun, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 45 (2016) 2976-3016. DOI:10.1039/C6CS00192K |

| [2] |

C.C. Winterbourn, H.M.B. Ampton, J.H. Livesey, A.J. Kettle, J. Biol. Chem. 281 (2006) 39860-39869. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M605898200 |

| [3] |

Z. Ye, R. Zhang, B. Song, et al., Dalton Trans. 43 (2014) 8414-8420. DOI:10.1039/c4dt00179f |

| [4] |

Y.H. Yan, H.L. Ma, J.Y. Miao, et al., Anal. Chim. Acta 1064 (2019) 87-93. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2019.03.004 |

| [5] |

Y. Chen, T. Wei, Z. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 28 (2017) 1957-1960. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.05.010 |

| [6] |

X.H. Zhou, Y.R. Jiang, X.J. Zhao, D. Guo, Talanta 160 (2016) 470-474. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2016.07.047 |

| [7] |

H. Ma, B. Song, Y. Wang, D. Cong, et al., Chem. Sci. 8 (2017) 150-159. DOI:10.1039/C6SC02243J |

| [8] |

S.Y. Yu, C.Y. Hsu, W.C. Chen, et al., Sens. Actuators B:Chem. 196 (2014) 203207. |

| [9] |

H. Xiong, L. He, Y. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 1075-1077. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.02.008 |

| [10] |

L. Yuan, W. Lin, J. Song, Y. Yang, Chem. Commun. 47 (2011) 12691-12693. DOI:10.1039/c1cc15762k |

| [11] |

C. Zhang, Q. Nie, I. Ismail, Z. Xi, L. Yi, Chem. Commun. 54 (2018) 3835-3838. DOI:10.1039/C8CC01917G |

| [12] |

L. Yuan, L. Wang, B.K. Agrawalla, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137 (2015) 5930-5938. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b00042 |

| [13] |

D. Shi, S. Chen, B. Dong, et al., Chem. Sci. 10 (2019) 3715-3722. DOI:10.1039/C9SC00180H |

| [14] |

P. Xing, Z. Zhang, Y. Niu, et al., Chem. Commun. 54 (2018) 9889-9892. DOI:10.1039/C8CC04631J |

| [15] |

J. Shi, Q. Li, X. Zhang, et al., Sens. Actuators B:Chem. 145 (2010) 583-587. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2009.11.003 |

| [16] |

Z. Wang, Y. Zhang, J. Song, et al., Anal. Chim. Acta 1051 (2019) 169-178. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2018.11.028 |

| [17] |

J. Kang, F. Huo, Y. Yue, et al., Dyes Pigm. 136 (2017) 852-858. DOI:10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.09.048 |

| [18] |

S. Goswami, A.K. Das, A. Manna, et al., Anal. Chem. 86 (2014) 6315-6322. DOI:10.1021/ac500418k |

| [19] |

L. Zeng, Y. Yuan, C. Jiang, et al., Dyes Pigm. 165 (2019) 408-414. DOI:10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.02.049 |

| [20] |

Z. Lou, P. Li, Q. Pan, K. Han, Chem. Commun. 49 (2013) 2445-2447. DOI:10.1039/c3cc39269d |

| [21] |

Q. Zhang, N. Zhang, Y.T. Long, X. Qian, Y. Yang, Bioconjug. Chem. 27 (2016) 341353. |

| [22] |

C. Chang, F. Wang, J. Qiang, et al., Sens. Actuators B:Chem. 243 (2017) 22-28. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2016.11.123 |

| [23] |

S.V. Mulay, M. Choi, Y.J. Jang, Y. Kim, S. Jon, Chemistry 22 (2016) 9642-9648. DOI:10.1002/chem.201601270 |

| [24] |

Q. Xu, K.A. Lee, S. Lee, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 9944-9949. DOI:10.1021/ja404649m |

| [25] |

Q. Xu, C.H. Heo, G. Kim, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 4890-4894. DOI:10.1002/anie.201500537 |

| [26] |

P. Stocker, M. Cassien, N. Vidal, Thetiot-Laurent S., S. Pietri, Talanta 170 (2017) 119-127. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2017.03.102 |

| [27] |

B. Zhu, P. Li, W. Shu, et al., Anal. Chem. 88 (2016) 12532-12538. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04392 |

| [28] |

B. Zhu, L. Wu, M. Zhang, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 107 (2018) 218-223. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2018.02.023 |

| [29] |

Q. Fu, G. Chen, Y. Liu, et al., Analyst 142 (2017) 1619-1627. DOI:10.1039/C7AN00244K |

| [30] |

Y. Zhou, W. Pei, C. Wang, et al., Small 10 (2014) 3560-3567. DOI:10.1002/smll.201303127 |

| [31] |

S.I. Reja, V. Bhalla, A. Sharma, G. Kaur, M. Kumar, Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 11911-11914. DOI:10.1039/C4CC05356G |

| [32] |

G. Cheng, J. Fan, W. Sun, et al., Analyst 138 (2013) 6091-6096. DOI:10.1039/c3an01152f |

| [33] |

W. Chen, W. Liu, X.J. Liu, et al., Talanta 162 (2017) 225-231. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2016.10.026 |

| [34] |

X. Chen, K.A. Lee, E.M. Ha, et al., Chem. Commun. 47 (2011) 4373-4375. DOI:10.1039/c1cc10589b |

| [35] |

G. Cheng, J. Fan, W. Sun, et al., Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 1018-1020. DOI:10.1039/C3CC47864E |

| [36] |

X. Cheng, H. Jia, T. Long, et al., Chem. Commun. 47 (2011) 11978-11980. DOI:10.1039/c1cc15214a |

| [37] |

J. Li, P. Li, F. Huo, et al., Dyes Pigm. 130 (2016) 209-215. DOI:10.1016/j.dyepig.2016.02.024 |

| [38] |

H. Yu, Y. Wu, Y. Hu, et al., Talanta 165 (2017) 625-631. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2017.01.015 |

| [39] |

J.O. Moon, J.W. Lee, M.G. Choi, S. Ahn, S.K. Chang, Tetrahedron Lett. 53 (2012) 6594-6597. DOI:10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.09.110 |

| [40] |

S. Goswami, S. Maity, A.C. Maity, A.K. Das, Sens. Actuators B:Chem. 204 (2014) 741-745. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2014.08.024 |

| [41] |

S. Goswami, S. Das, K. Aich, et al., RSC Adv. 4 (2014) 24881-24886. DOI:10.1039/C4RA03200D |

| [42] |

W.C. Chen, P. Venkatesan, S.P. Wu, Anal. Chim. Acta 882 (2015) 68-75. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2015.04.012 |

| [43] |

C. Liu, F. Wang, T. Xiao, et al., Sens. Actuators B:Chem. 256 (2018) 55-62. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2017.09.198 |

| [44] |

F.J. Huo, J.J. Zhang, Y.T. Yang, Sens. Actuators B:Chem. 166-167 (2012) 4449. |

| [45] |

X. Lou, Y. Zhang, Q. Li, J. Qin, Z. Li, Chem. Commun. 47 (2011) 3189-3191. DOI:10.1039/c0cc04911e |

| [46] |

Standardization Administration of the People's Republic of China (SAC) has set the drinking water sanitary standard (GB5749-2006). http://www.sac.gov.cn/.

|

2020, Vol. 31

2020, Vol. 31