Graphene oxide (GO) [1, 2], as a reliable graphene derivative [3-5], has attracted significant attention for its rich functional groups, atomic thickness and high surface area [6-8], holding broad applications, such as macroscopically assembled material [9, 10], biochemistry [11], electronics [12-14], nanomedicine [15, 16]. The processing of GO usually relies on the fluid assembly method and its aqueous dispersed system has become an important processing stock of GO [17]. As complexed with metal ions in aqueous dispersions, GO has been utilized to prepare crosslinked materials with high mechanical strength [18], metal oxide composite materials for energy storage [19] and adsorption materials for hazard substances [20]. In this context, understanding the dispersion behavior of GO under the existence of metal ions is fundamentally important for its wide applications in complex hybrids and environment treatment.

Generally, GO can disperse homogeneously in aqueous system due to the rich hydrophilic functional groups, mainly including epoxide, phenolic hydroxyl, and carboxylic groups [8, 21]. The negatively charged carboxylic groups provide strong electrostatic repulsion force to avoid stacking [21, 22], allowing GO as a versatile chemical precursor for fluid processing. Previous researches have investigated the dispersive state of GO in aqueous surroundings, in the frame of static EDL mechanism [23-26]. In aqueous surroundings, the stability of GO strongly depends on the ionic strength (IS), pH and salt types [24, 25, 27, 28]. The increase of IS can induce compression of EDL of dispersed GO [23-26], and lead to a decrease of electrostatic repulsion between GO sheets. GO prefers to aggregate gradually at low pH (acidic), while it disperses well at high pH (basic) due to the higher degree of deprotonation of carboxylic functional groups on GO sheets [24, 28]. Adding metal salt into GO dispersion usually gives immediate aggregation because of the shielding effect of solvated ions [23, 29]. The aggregation degree is positively correlated with the valence state of the metal cations according to the Schulze-Hardy rule [30], suggesting that the ionic strength plays an important role in determining the stability of GO suspension [24, 29]. Gao et al. [25] reported the influence of cations (Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+ and Al3+) and anions (Cl, HCO3-, HPO42- and SO42-) on static dispersion behavior of GO. They found the tendency of GO to agglomerate decreases in the order of Ca2+ > Mg2+ > K+ ≈ Na+. Ren et al. [26] revealed that the aggregation of GO and its deposition on Al2O3 depended on the solution pH value and the types and concen-trations of electrolytes. Although the static dispersion of GO has been established, the dynamic stability of GO considering ions exchange still keeps an open question.

Here, we investigated the dynamic dispersion stability of GO with metal ions. GO gets aggregated when mixing with most metal cations (Na+, Mg2+, Al3+, etc.) over a wide range of concentrations. We found an unexpected redispersion behavior of GO for Fe3+ ions under ion exchange. A dynamic mechanism of EDL was proposed to explain the reversal of ζ potential [31] of GO-Fe3+ system and the redispersion behavior of GO in Fe3+ system. We revealed that the dynamic change of repulsion potential energy (Er) between GO sheets governs the dispersion state of GO-cation system. The intrinsic adsorption mechanism between GO and Fe3+ is system-atically investigated. The shielding effect and strong complexion ability of Fe3+ with GO enable the selective redispersion behavior, which is distinct from other ions. This study complements the understanding of dynamic dispersion stability of GO and guides the design and preparation of graphene metal hybrids and composites.

Aqueous dispersion GO sheets (2.5 mg/mL) with lateral size of 30 μm (GO-3) and 5 μm (GO-1), thickness of 1 nm, was obtained from Hangzhou Gaoxi Technology Co., Ltd. (www.gaoxitech.com). All metal ions supplied in this work are in the form of MCln (where M is Na, Mg, Ca, Cu, Co, Ni, Al and Fe), which were purchased from Aladdin Co., Ltd. All other reagents were analytical grade and were used without further purification

GO dispersion was diluted to ~0.1 mg/mL. A certain amount of MCln was dissolved in deionized water and added into the 5.00 mL of GO dispersion slowly under stirring, forming GO-Mn+ mixed dispersion with different concentration from 0.04 mmol/L to 0.2 mol/L. Specifically, GO with Fe3+ under high ion concentration (the mass ratio of Fe3+ to GO was 6:1) was studied intensively, which was defined as GO-Fe3+ complex. GO-1 and GO-3 were explored to react with Fe3+ under high ion concentration.

After agitated in a conditioning mixer (AR-100) at 25 C for 10 min, 500 μL GO-Mn+ mixed dispersion of various ionic concentration were used immediately for measurement of ζ potential on a ZET-3000HS apparatus. Macroscopic photos were taken by Canon 600D. Optical microscope photographs of the redispersed GO in GO-Fe3+ system and the GO in pure water were obtained using a Nikon E600POL. SEM images were taken on Hitachi S4800 field emission scanning electron microscope to characterize the surface morphologies. For atomic force microscopy (AFM) studies, a droplet of GO and GO-Fe3+complex dispersion were cast onto freshly cleaved mica, dried by spin-coating method, and investigated using an Agilent 5500A atomic force microscope in the tapping mode. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were carried out on a PHI 5000C ESCA system operated at 14.0 kV, and all of the binding energies were referenced to the C 1s neutral carbon peak at 284.8 eV.

The EDTA-2Na solution was added into the GO-Fe3+ system to react with the Fe3+ at the mole ratio of EDTA2- : Fe3+ = 1:1 and EDTA2- : Fe3+ = 2:1. ζ potential was applied to evaluate the dispersion state of the four kind of suspension: GO, GO-Fe3+ complex, EDTA2- /Fe3+ (1:1) and EDTA2- /Fe3+ (2:1). Photographs was taken to show the visual changes of the four suspension. Furthermore, XPS survey spectra results demonstrate the elements contained of the four suspension above.

The GO-Cu2+ aggregates were prepared by adding a certain amount of Cu2+ at the mass ratio of Cu2+:GO = 20:1. Then Fe3+ of same concentration of Cu2+ was added into the GO-Cu2+ aggregates. ζ potential was applied to evaluate the dispersion state of the suspension as the increase of concentration of Fe3+.

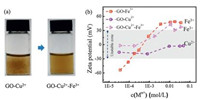

The homogenously dispersed GO sheets get agglomerated immediately when adding metal ions, such as Mg2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Al3+, etc. (Fig. 1a and Fig. S1 in Supporting information). The typical immediate agglomerate states of GO in the presence of different valence of cations (Na+, Mg2+, Fe3+) are shown in Fig. 1a. Both Na+ and Mg2+ induce aggregation of GO under a low ionic concentration and the precipitation aggravates at higher concentrations. As shown in Fig. 1b, the ζ potential of GO increases to ±30 mV as the concentration of Na+ and Mg2+ increases, denoting the colloidal instability according to criterion of colloidal stability [32]. The introduced metal cations could get absorbed with functionalities on GO sheets by electrostatic attraction, leading to the compression of EDL. In this case, the potential difference between the interface of GO sheets and the solution body, that is, the absolute value of ζ potential, is reduced. As a result, the decreased repulsion force between GO sheets induces the aggregation, similar to previous reports [22, 29, 33].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (a) Digital images of the GO-Mn+ dispersions with the increasing ionic concentration. (b) Zeta (ζ) potential of the GO-Mn+ as a function of the concentration of Na+, Mg2+ and Fe3+, respectively. Optical microscope images of the redispersed GO in GO-Fe3+ system (c) and GO in pure water (f). SEM images of the redispersed GO in GO-Fe3+system (d) and GO in pure water (g). AFM images of the redispersed GO in GO-Fe3+ system (e) and GO in pure water (h). | |

In aggregated dispersions of GO, we continuely increased the metal ion concentration and found an unexpected redispersion of GO in Fe3+ system. We observed that GO aggregates induced by a small amount of Fe3+ get dispersed homogenously again as Fe3+ concentrations increasing after long time stirring for 1 h. As shown in Fig. 1a, the aggregated dispersion at the mass ratio of Fe3+ to GO of 1:20 turned homogenous dispersion as the ratio of Fe3+ to GO increased to 6:1. This observation is anti-intuitive as compared with the aggregation trend of GO in high metal ion concentrations (Fig. S1 and Ref. [23-26]). We tracked the ζ potential change as the Fe3+ ionic concentration increases and detected that the ζ potential passes through the unstable zone (-30 mV to +30 mV) to reach +45 mV at the Fe3+ ionic concentration of 10 mmol/L (Fig. 1b). This high reversal charged ζ potential in Fe3+ system means a good dispersibility of GO. As a comparison, divalent ions, including Mg2+, Cu2+, Ni2+, Co2+, Ca2+, turned the ζ potential to reach the zone in the range from -5 mV to 30 mV (Fig. S1). Another trivalent cation of Al3+ also exhibit a slight inversion of ζ potential to reach +10 mV, smaller than the stable one (+45 mV) in the case of Fe3+. In addition, the same ζ potential reversion was observed in GO sheets with lateral sizes of 5 μm (GO-1) and 30 μm (GO-3) as interacted with Fe3+ (Fig. S2 in Supporting information). The concentration of GO with a wide range (from 0.1 mg/mL to 5 mg/mL) has a negligible influence on the stability of GO-Fe3+ suspension (Fig. S3 in Supporting information).

We used optical microscopy, SEM and AFM to confirm the single layer state of the redispersed GO in Fe3+ system. As shown in Figs. 1c and d, the redispersed GO sheets in concentrated Fe3+ solution independently spread on the substrate in a flat state, similar to the state of GO in pure water (Figs. 1f and g). The redispersed GO sheet has a thickness of 3.12 nm measured by AFM (Fig. 1e), which is much thicker than that (1.13 nm) of GO in pure water (Fig. 1h), indicating the presence of Fe3+ layers on both sides of redispersed GO sheets.

The observed redispersion behavior of GO in Fe3+ is distinct from the usual precipitation [23-25]. From the classical EDL theory, the continuous increasing concentration of ions inevitably brings more severe precipitation for the enhanced shielding effect, which is contrast to our observed redispersion behavior. We reasoned that the classic EDL theory describes the static dispersion state of colloids and ignores the dynamic interaction between colloids and ions. Thus, we proposed a dynamic mechanism of EDL theory to explain the unusual redispersion behavior of GO-Fe3+ system, by considering the exchange interaction with Fe3+ ions.

The redispersion mechanism of GO with Fe3+ was illustrated in Fig. 2a. Firstly, in the absence of Fe3+, GO sheets dispersed in water carry a denser layer of H+ and a diffusion layer of H+ for the ionization of carboxyl functional groups. In Fig. 2b, GO dispersion remains stable since the repulsion potential energy (Er) induced by repulsion between negative charges is larger than adsorption potential energy (Ea) according to the DLVO theory [34, 35]. Secondly, a small quantity of Fe3+ less than coordinated sites of GO sheets can exchange with H+ absorbed on GO sheets. As more Fe3+ ions penetrate the denser layer, EDL gets compressed, resulting in the decrease absolute value of ζ potential and Er. The breakup of balance between Er and Ea leads to immediate flocculation of GO sheets (Fig. 2b). Further increasing Fe3+ gradually exchange with H+ on coordinated sites of GO sheets. The diffusion layer disappears and the ζ potential can reach to zero. In the dynamic range, the increased Fe3+ continuously occupies the coordinated sites on GO till the density overwhelms the negatively charged sites. GO sheets become wrapped by a large amount of Fe3+ and covered by positive charges. Diffusion layer of EDL also expanded by the excess Fe3+, leading to the increase of Er. As a result, precipitated GO was driven to be isolated to become individual sheets by repulsion of surface positive charges (Fig. 2b).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) Schematic of dynamic electric double layer (EDL) mechanism, showing the evolution of EDL on the surface of GO sheets with loading Fe3+. (b) The corresponding diagram of GO-Fe3+ dispersion during this process. | |

In this dynamic EDL mechanism, the exchange with Fe3+ ions drives the reversion of ζ potential and the redispersion behavior of GO-Fe3+ system. The dispersion state of all GO-Mn+ (where M are Na, Mg, Ca, Cu, Co, Ni, Al and Fe) colloids were examined (Fig. S1). The change of ζ potential depends on not only the concentration but also the valence of the added cation. In Fig. S1, only the ζ potentials of GO-Al3+ and GO-Fe3+ systems inverse from negative to positive at higher concentration. The results above can be explained by the Schulze-Hardy rule [30]: Cations (Al3+ and Fe3+) with higher valences provide stronger charge screening capability than lower valence cations at the same concentration. As a result, Al3+ and Fe3+ exhibit higher efficiency in increasing the absolute value of ζ potential of GO. Theoretically, the cations with the same valence should produce similar charge screening effects. However, the GO-Al3+ system does not pass through the +30 mV threshold and results a temporary stability after the potential reversal as in the case of GO-Fe3+ system, suggesting that the coordination between GO and metal cations possibly has a strong influence on the stability of redispersed GO, not only depending on the electrostatic attraction induced by EDL.

For the GO-Fe3+ system, the redispersion process is accompanied by surface adsorption. Metal cations are reported to be bound to the surface through electrostatic attraction with carboxylic groups on GO sheets [25]. However, there is still confusion whether any other interactions were involved. We prepared GO-Fe3+ complex to analyze the interaction between GO and Fe3+. XPS spectra revealed that the adsorption of Fe3+ onto GO depends not only mainly on electrostatic attraction but also highly on complexation with oxygen-containing groups. The spectra (Fig. 3a) of neat GO, GO-Fe3+ complex show a predominant graphitic C 1s peak at 285.0 eV and an O 1s peak at 532.0 eV [36, 37]. By contrast, the characteristic Fe 2p peak is clearly observed at 711.0 eV in GO-Fe3+ complex [36, 37]. The Fe content of GO-Fe3+ complex is 6.26%, demonstrating that there is a large portion of Fe3+ ions tightly loaded on the GO after repeated washing. Fig. 3b shows a pair of peaks at 710.8 eV and 724.2 eV that are assigned to Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 [36, 37], respectively, indicating the formation of Fe-O coordination according to the Binding Energy Contrast Table. The O1s spectra of GO and GO-Fe3+ complex were depicted in Figs. 3c and d. For GO sample, the O1s spectra (Fig. 3e) is deconvoluted into two peaks at 531.8 eV and 533.0 eV, which can be attributed to oxygen containing functional groups, that are, C=O and C-O, respectively [38]. For GO–Fe3+ complex sample, a new peak at 530.0 eV in Fig. 3d is assigned to the Fe-O [38], in correspondence to the formation of Fe-O complexation. The C 1s spectra of GO and GO-Fe3+ complex were illustrated in Fig. S4 (Supporting information). The content of C=O and O=C-O-H decreased severely after GO reacting with Fe3+, demonstrating that the Fe3+ is coordinated with C=O and O=C-O-H on GO sheets.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. XPS spectra of GO and GO-Fe3+ complex at full survey (a). Fe 2p spectra of GO-Fe3+ complex (b). O 1s spectra of GO (c) and GO-Fe3+ complex (d). | |

The XPS analysis confirms our deduction that the interaction between GO and metal cations involves a complexation mechanism, beyond the simple electrostatic attraction. Although a variety of functional groups on GO, including carboxyl, carbonyl, epoxy and hydroxyl can coordinate with cations, to simplify the problem, we assume that complexation occurs primarily on the carboxyl groups. Complexation stability constants for the acetic acid-Mn+ system [39] were used to estimate for the GO-Mn+ system. Specifically, the complexation stability constant for Fe3+ and Al3+-acetic acid complexes are logK = 4.29 and 3.43, respectively. Therefore, GO-Fe3+ complex has a stronger coordination capability than GO-Al3+ complex. The Fe3+ is more efficient in increasing the ζ potential values of GO and enables the redispersion behavior.

We further demonstrated the complexation interaction between GO and Fe3+ dominating the redispersion behavior. According to the adsorption mechanisms, the removal of the bound Fe3+ from GO-Fe3+ complex may lead to aggregations. We added ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt (EDTA-2Na) to the GO-Fe3+ homogeneous dispersion slowly at a ratio of EDTA2- :Fe3+ = 1:1 and EDTA2- :Fe3+ = 2:1. The transition of dispersion state during this process is shown in Fig. 4a. The corresponding variation of ζ potential of the four dispersions precisely evaluates the dispersion state. In stage 1, GO sheets dispersed homogenously and the corresponding ζ potential is 40 mV. In stage 2, an excess amount of Fe3+ was added into the GO dispersion. GO-Fe3+ system remains stable but the ζ potential increased to +47 mV, which can be explained by the dynamic mechanism of EDL theory we proposed above. XPS spectra (Fig. 4b) also declare the existence of Fe3+ ions in stage 2. In stage 3, the GO-Fe3+ dispersion gets unstable upon adding EDTA2- at a ratio of EDTA2- :Fe3+ = 1:1. The ζ potential in this system turned to 15 mV, indicating the broken balance between Er and Ea in the presence of EDTA2-. In stage 4, with further adding EDTA2- at the ratio of EDTA2- :Fe3+ = 2:1, the flocculation disappears absolutely and the ζ potential recovers to 30 mV. XPS spectra (Fig. 4b) results show that a very small amount of Fe is detected in the EDTA2- /Fe3+ (1:1) system while the EDTA2- /Fe3+ (2:1) has no Fe peak at all, demonstrating that coordinated Fe3+ of GO-Fe3+ complex has been entirely removed by chelating with EDTA2-. The results are consistent with our expectation that only the completely removal of Fe3+ from GO sheets results in the redispersion of GO sheets as original negatively charged state.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) ζ potential and the corresponding digital images of the redispersed GO in the four kinds of dispersion: GO, GO-Fe3+ complex, EDTA2- /Fe3+ (1:1) and EDTA2- /Fe3+ (2:1). GO-Fe3+ complex redispersed homogeneously when the mole ratio of EDTA2- /Fe3+ is adjusted to 2:1. (b) XPS spectra of GO, GO-Fe3+ complex, EDTA2- /Fe3+ (1:1) and EDTA2- /Fe3+ (2:1). Fe3+ fails to be detected in EDTA2- /Fe3+ (2:1) system, indicating that Fe3+ was removed through chelating with EDTA2-. | |

The redispersion of GO-Fe3+ system may provide an effective method to tune GO stability by considering dynamic interaction between GO and ions. In Fig. 5a, GO-Cu2+ system aggregates at the mass ratio of 20:1 (Cu2+:GO). The addition of excess Fe3+ (mass ratio of Fe3+:GO is also 20:1) made the GO-Cu2+ aggregates redisperse because of the stronger adsorption capability for Fe3+ with GO. Fe3+ could replace Cu2+ on absorbed sites of GO, and then a repulsion between positive charges formed once Fe3+ surpass the threshold. The ζ potential evolution of GO-Cu2+, GO-Fe3+, GO-Cu2+-Fe3+ was shown in Fig. 5b. GO-Cu2+ system is in unstable region under a wide range of Cu2+ concentration, different from GO-Cu2+-Fe3+ system which gets stable when the concentration of Fe3+ is beyond 4.7 mmol/L.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) Digital images of GO-Cu2+ dispersion and GO-Cu2+-Fe3+ dispersion. (b) ζ potential of the three kinds of dispersion: GO-Cu2+, GO-Fe3+ and GO-Cu2+-Fe3+. GO-Cu2+ system is unstable under a wide range of Cu2+ concentration, whereas the GO-Cu2+-Fe3+ system gets stable when the concentration of Fe3+ is beyond 4.7 mmol/L. | |

On the other hand, we found that the introduction of metal ions (M+ and M2+) has a negligible effect on the stability of GO-Fe3+ complex, through examining the dispersed state by optical microscopy (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). Taking Ca2+ as an example, GO-Fe3+-Ca2+ system kept stable (> ±30 mV) in a wide Ca2+ concentration range up to 0.2 mol/L (Fig. S6 in Supporting information). The stability of GO-Fe3+-Mn+ complex denotes that the adsorption capability for Fe3+ with GO is stronger than other ions.

In summary, we investigated the dynamic dispersion stability of GO with metal ions and found a redispersion behavior in concentrated Fe3+ solution, other than permanent aggregation. The exchange with Fe3+ ions drives the reversion of ζ potential and enables the redispersion to individual GO-Fe3+ complex sheets, following a dynamic EDL mechanism. The specifically strong electrostatic shielding effect and coordination attraction between Fe3+ and functional oxygen groups of GO allow the selective redispersion in concentrated Fe3+ solution. The revealed dynamic dispersion stability complements our understanding on the dispersive stability of GO and can be utilized to fabricate graphene-metal hybrids for rich applications.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51533008, 51603183, 51703194, 51803177, 21805242 and 5197030056), National Key R & D Program of China (No. 2016YFA0200200), Fujian Provincial Science and Technology Major Projects (No. 2018HZ0001-2), Hundred Talents Program of Zhejiang University (No. 188020*194231701/113), Key Research and Development Plan of Zhejiang Province (No. 2018C01049), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. 2017QNA4036, 2017XZZX001-04), Foundation of National Key Laboratory on Electromagnetic Environment Effects (No. 614220504030717). We thank Dr. Hua Li for helps on vibration experiments.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementarymaterial related to this article canbefound, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2019.10.010.

| [1] |

D.R. Dreyer, S. Park, C.W. Bielawski, R.S. Ruoff, Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 (2010) 228-240. DOI:10.1039/B917103G |

| [2] |

J. Kim, L.J. Cote, J. Huang, Acc. Chem. Res. 45 (2012) 1356-1364. DOI:10.1021/ar300047s |

| [3] |

Z. Liu, Z. Xu, X. Hu, C. Gao, Macromolecules 46 (2013) 6931-6941. DOI:10.1021/ma400681v |

| [4] |

Z. Weng, Z. Xu, C. Gao, Sci. China Chem. 57 (2014) 605-614. DOI:10.1007/s11426-013-5060-0 |

| [5] |

A.M. Dimiev, J.M. Tour, ACS Nano 8 (2014) 3060-3068. DOI:10.1021/nn500606a |

| [6] |

S. Yang, C. Chen, Y. Chen, et al., ChemPlusChem 80 (2015) 480-484. DOI:10.1002/cplu.201402284 |

| [7] |

C.N. Yeh, K. Raidongia, J. Shao, Q.H. Yang, J. Huang, Nat. Chem. 7 (2014) 166-170. |

| [8] |

B.J. Hong, O.C. Compton, Z. An, I. Eryazici, S.B.T. Nguyen, ACS Nano 6 (2012) 63-73. DOI:10.1021/nn202355p |

| [9] |

M. Zhang, L. Huang, J. Chen, C. Li, G. Shi, Adv. Mater. 26 (2014) 7588-7592. DOI:10.1002/adma.201403322 |

| [10] |

F. Guo, X. Zheng, C. Liang, et al., ACS Nano 13 (2019) 5549-5558. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.9b00428 |

| [11] |

J. Zhang, F. Zhang, H. Yang, et al., Langmuir 26 (2010) 6083-6085. DOI:10.1021/la904014z |

| [12] |

Y. Shao, J. Wang, H. Wu, et al., Electroanal. 22 (2010) 1027-1036. DOI:10.1002/elan.200900571 |

| [13] |

T. Huang, X. Chu, S. Cai, et al., Energy Storage Mater. 17 (2019) 349-357. DOI:10.1016/j.ensm.2018.07.001 |

| [14] |

K.S. Kim, Y. Zhao, H. Jang, et al., Nature 457 (2009) 706-710. DOI:10.1038/nature07719 |

| [15] |

X. Sun, Z. Liu, K. Welsher, et al., Nano Res. 1 (2008) 203-212. DOI:10.1007/s12274-008-8021-8 |

| [16] |

B. Tian, C. Wang, S. Zhang, L. Feng, Z. Liu, ACS Nano 5 (2011) 7000-7009. DOI:10.1021/nn201560b |

| [17] |

Z. Xu, H. Sun, X. Zhao, C. Gao, Adv. Mater. 25 (2013) 188-193. DOI:10.1002/adma.201203448 |

| [18] |

S. Park, K.S. Lee, G. Bozoklu, et al., ACS Nano 2 (2008) 572-578. DOI:10.1021/nn700349a |

| [19] |

P.Y. Chen, M. Liu, T.M. Valentin, et al., ACS Nano 10 (2016) 10869-10879. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.6b05179 |

| [20] |

N. Zhang, H. Qiu, Y. Si, W. Wang, J. Gao, Carbon 49 (2011) 827-837. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2010.10.024 |

| [21] |

L.J. Cote, F. Kim, J. Huang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (2009) 1043-1049. DOI:10.1021/ja806262m |

| [22] |

D. Li, M.B. Müller, S. Gilje, R.B. Kaner, G.G. Wallace, Nat. Nanotechnol. 3 (2008) 101-105. |

| [23] |

K. Yang, B. Chen, X. Zhu, B. Xing, Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 (2016) 11066-11075. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.6b04235 |

| [24] |

L. Wu, L. Liu, B. Gao, et al., Langmuir 29 (2013) 15174-15181. DOI:10.1021/la404134x |

| [25] |

Y. Gao, X. Ren, X. Tan, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 335 (2017) 56-65. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.04.027 |

| [26] |

X. Ren, J. Li, X. Tan, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 48 (2014) 5493-5500. DOI:10.1021/es404996b |

| [27] |

X. Wang, H. Bai, G. Shi, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (2011) 6338-6342. DOI:10.1021/ja200218y |

| [28] |

I. Chowdhury, N.D. Mansukhani, L.M. Guiney, M.C. Hersam, D. Bouchard, Environ. Sci. Technol. 49 (2015) 10886-10893. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.5b01866 |

| [29] |

M. Wang, Y. Niu, J. Zhou, et al., Nanoscale 8 (2016) 14587-14592. DOI:10.1039/C6NR03503E |

| [30] |

M. Sano, J. Okamura, S. Shinkai, Langmuir 17 (2001) 7172-7173. DOI:10.1021/la010698+ |

| [31] |

T. Jimbo, M. Higa, N. Minoura, A. Tanioka, Macromolecules 31 (1998) 63-68. |

| [32] |

B. Konkena, S. Vasudevan, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3 (2012) 867-872. DOI:10.1021/jz300236w |

| [33] |

K.A. Huynh, K.L. Chen, Environ. Sci. Technol. 45 (2011) 5564-5571. DOI:10.1021/es200157h |

| [34] |

T. Cao, G. Trefalt, M. Borkovec, Langmuir 34 (2018) 14368-14377. DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b03191 |

| [35] |

Y. Li, M. Girard, M. Shen, J.A. Millan, M. Olvera de la Cruz, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114 (2017) 11838-11843. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1713168114 |

| [36] |

R. Liu, X. Zhu, B. Chen, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 1-11. DOI:10.1038/s41598-016-0028-x |

| [37] |

H.P. Cong, X.C. Ren, P. Wang, S.H. Yu, ACS Nano 6 (2012) 2693-2703. DOI:10.1021/nn300082k |

| [38] |

M.D. Sánchez, P. Chen, T. Reinecke, M. Muhler, W. Xia, ChemCatChem 4 (2012) 1997-2004. DOI:10.1002/cctc.201200286 |

| [39] |

M. Liu, P.Y. Chen, R.H. Hurt, Adv. Mater. 30 (2018) 1-8. |

2020, Vol. 31

2020, Vol. 31