Disulfides are relatively stable products of thiol oxidation and play important roles in determining the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of proteins [1]. Moreover, disulfides are abundantly existed in the natural products and have wide applications at various industrial levels, which is mainly linked with their outstanding redox chemical characteristics [2]. The superiority on redox sensitivity has made the disulfide bond bridge vital in drug delivery program [3]. In the field of physiology, the disulfide bonds are crucial building scaffolds for the stabilization of the folded form of proteins [4, 5] and for the control of enzymes activity [6]. Moreover, thiols exhibit serious negative effects on human health and natural environment because of their high toxicity and pollution [7, 8]. Thus, the oxidation of thiols is also of environmental significance.

Due to the importance of disulfides in both biological and chemical systems, the synthesis of them received much attention. For its application on organic synthesis, on one hand, the disulfides are used as the available reagents to realize the sulfenylation of some organic compounds [9-11]; on the other hand, as the protection group of thiols, disulfides are more stable in some conversions [12], and they are not foul smelling just as the thiol ones. With the benefits from the above, various methods for the synthesis for the disulfides have been reported in the past few decades, but the oxidation of thiols to disulfides is still the most common strategy [13]. In order to alleviate the negative issue that the thiols were prone to be overoxidized [14, 15], extensive types of oxidants, including H2O2 [16], halogens and derivatives [17], KMnO4/CuSO4 [18] and sulfoxide [19], had been taken to implement the controlled oxidation tests. The target disulfides could be obtained efficiently, but those methods commonly held the main drawback: Toxic oxidant input and waste output all in stoichiometric amounts. Fortunately, O2 or aerial O2 emerges as the optimal oxidant from the cost-efficient and eco-friendly perspective and has gained great achievements on this type of transformation.

TiO2 is one of the most famous semiconductor photocatalysts [20]. However, it needs UV light rather than visible light illumination to overcome its band gaps. Visible light, served as an easily available energy source to motivate and split organic molecules into highly active radicals in reactions [21-25], has widely extended its application in laboratory. When it came to the issue of oxidation of thiols to disulfides, this method has brought significant achievements and turned out to be one of the most promising strategies [26-28]. The classical approaches for the transformation from thiols to disulfides (Scheme S1 in Supporting information) usually accompanied by the consumption of extra sacrificial reagent, CdSe QDs (quantum dots) exhibited considerable efficiency under visible light irradiation at room temperature without any additives [29], and the strategy was highlighted by releasing hydrogen as the exclusive byproduct. But actually, more substantial efforts were made toward the themes of exploiting green oxidant O2 and metal-free photocatalysis. Recently, rose bengal, an organic dye, had successfully induced the oxidation coupling of thiols to disulfides under white light-emitting diodes (LEDs) at room temperature by using an efficient micro-flow reaction device [30]. Under similar reaction conditions, Another organic dye Eosin Y could also photocatalyze the transformation with excellent yields of disulfides and a wide scope of thiols, but equilmolar of additive tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) was essential to shorten reaction time [31].

In this contribution, we would like to report a more facile and efficient protocal on the selective oxidation of thiols into disulfides including symmetrical and unsymmetrical ones. Employing O2 as a terminal oxidant and TEMPO as a photocatalyst, this protocol was demonstrated with an extraordinarily high efficiency and disulfides could be obtained in high isolate yields (≥86%) at room temperature without any additives, along with a broad selectivity, substrate scope as well as excellent functional group compatibility. This work demonstrates the versatile role of TEMPO that could potentially play in visible lightpromoted selective organic transformations.

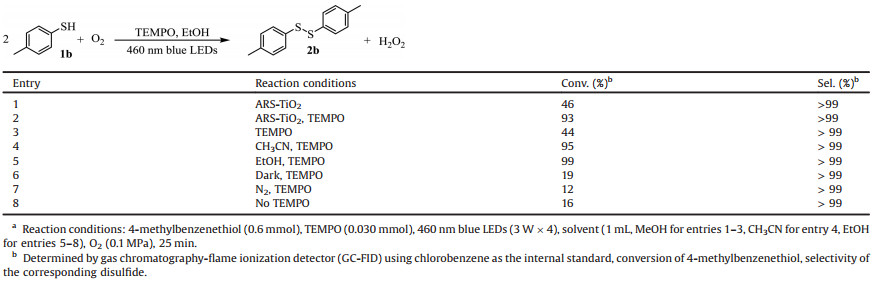

This research was commenced based on our two previous studies regarding the selective aerobic oxidation of sulfides into sulfoxides by cooperative photocatalysis with TEMPO [32, 33]. Beforehand, might be plausible for the oxidation of thiols which can be viewed as a simple extension of our previous studies. To this hypothesis, we employed 4-methylbenzenthiol 1b as the probe substrate under conditions quite similar to our previous studies, because TEMPO is a very good hydrogen abstraction agent. With alizarin red S-sensitized TiO2 (ARS-TiO2) as the photocatalyst, selective oxidation of 4-methylbenzenethiol into disulfide 2b proceeded well (entry 1, Table 1). Adding TEMPO could considerably promote the yield of disulfide (entry 2, Table 1). These results were very promising at an early stage which might validate our hypothesis. Thereafter, we furthered our rigorous control experimental process. Quite unexpectedly, without the presence of ARS-TiO2, disulfide 2b could be yielded in 44% smoothly in methanol (MeOH) after dropping 5 mol% of TEMPO into the reaction mixture excited by 460 nm blue LEDs (entry 3, Table 1), suggesting TEMPO itself can be a photocatalyst for this specific reaction. Even though these results indicate that our previous cooperative photocatalysis with TEMPO did not reign for selective oxidation of thiols, we were quite happy to uncover the hitherto unknown photocatalytic activity of TEMPO. Motivated by this result, we were pleased to discover that ethanol (EtOH) acted as a much better solvent than CH3OH and CH3CN for this photocatalytic reaction (entries 3–5, Table 1). Moreover, EtOH is a bio-compatible solvent which is also advantageous for the application of this protocol in bio-related scenario. Metal-free photocatalysis is particularly suitable to bio-friendly conditions [34]. We did more investigations on the photocatalytic selective oxidation reactions. Concluded from entries 6–8 of Table 1, we confirmed that visible light, O2 and TEMPO made up the necessary components for the photocatalytic synthesis of disulfide 2b. Low pressure O2 (0.1 MPa) and a closed Pyrex reactor was selected to prevent the emitting of odor of thiols. Note that the reaction can proceed smoothly with aerial O2.

|

|

Table 1 Control experiments for the visible light promoted selective aerobic oxidation of 4-methylbenzenethiol 1ba. |

After the establishment of TEMPO as a photocatalyst for the selective aerobic oxidation of thiol, we subsequently did some additional screening experiments to make more evident its importance. As such, we evaluated the influence of different kinds and amounts of TEMPO on the photocatalytic aerobic oxidation reaction which were summarized in Tables S1 and S2 (Supporting information). Known from Table S1, TEMPO would be preferred as the photocatalyst from the views of efficiency and commercial cost. From the results in Table S2, it was reasonable to employ 5 mol% of TEMPO (30 μmol) as an optimized quantity. Finally, we would like to continue the investigation with the following optimized conditions: 0.6 mmol of thiol, 5 mol% of TEMPO photocatalyst, 460 nm blue LED irradiation, 1 mL of EtOH solvent and 0.1 MPa of O2.

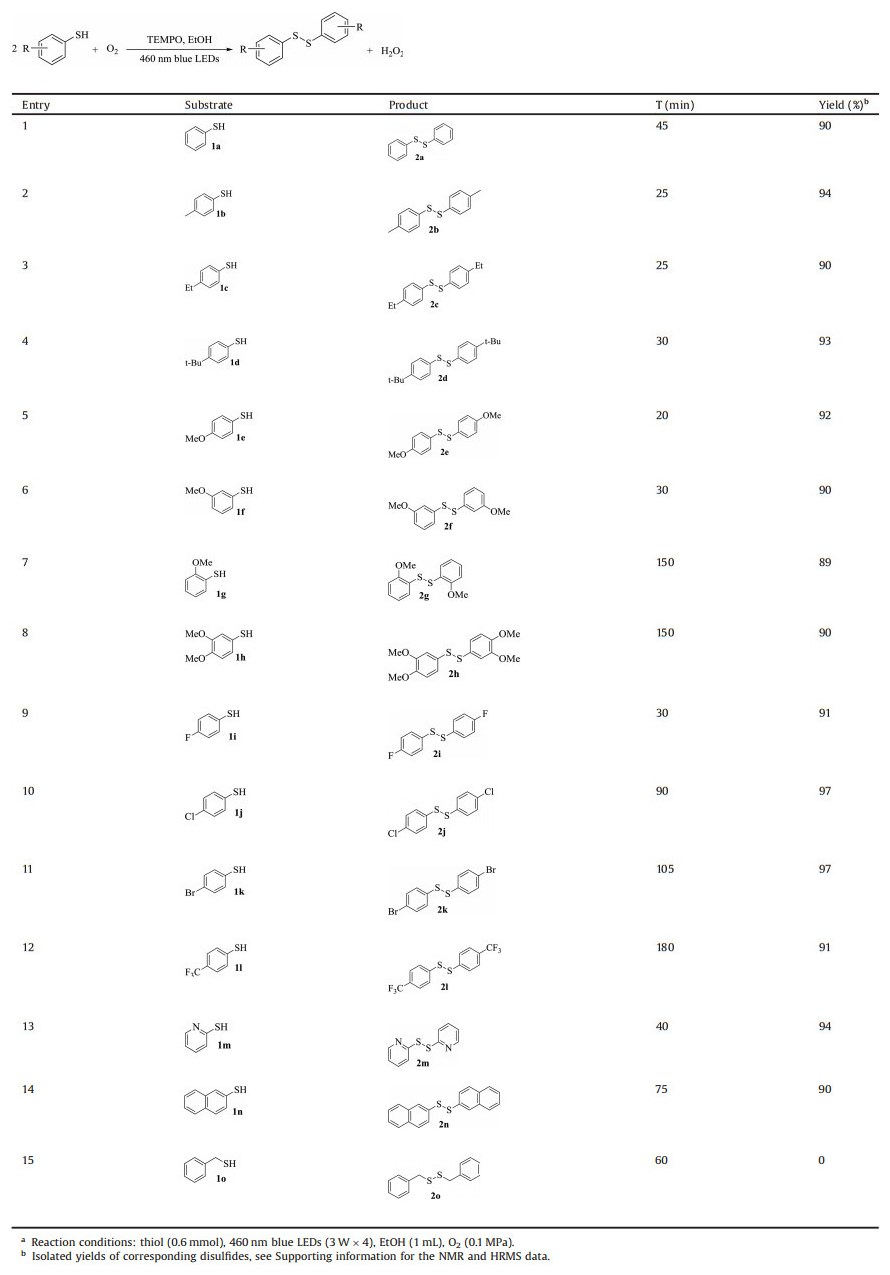

The scope of thiols was further investigated under the optimal reaction conditions. As showed in Table 2, we first examined the aerobic oxidation of benzenethiol 1a and this transformation was accomplished in 45 min (traced by thin-layer chromatography) with an isolated yield of 90% (entry 1, Table 2). When the para-substituted thiols bearing electron donating groups on the benzene ring (entries 2–5, Table 2) were tested, it was found that the reaction rate, according to the reaction time, had a positive correlation with the ability of electron donation of substrate. Additionally, the ortho-substituted thiol 1 g (entry 7, Table 2) needed much longer irradiation time than the para- and meta-substituted thiols (entries 5 and 6, Table 2) to accomplish the oxidation coupling. This sluggish performance could ascribe mainly to its unique steric hindrance. Analogously, the disubstituted thiol 1 h (entry 8, Table 2) also required a longer reaction time. Subsequently, after some other attempts on substrates bearing electron withdrawing groups (entries 9–12, Table 2), we concluded that they needed much longer irradiation time than those ones possessing electron donating groups. From a view of electronic effect, it could be concluded that the electron donating group makes a positive contribution to stabilizing the generated radical intermediates in the conversion. Conveniently, these attempts showed a tolerance to various functional groups (F, Cl, Br, CF3). The protocol was also suitable for the hetero-(1m) and poly-aromatic (1n) thiols (entries 13 and 14, Table 2).

|

|

Table 2 Visible light photocatalytic selective aerobic oxidative synthesis of disulfides by TEMPO. a |

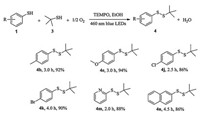

This visible light photocatalytic protocol was inadequate to convert aliphatic thiol 1o into disulfide 2o (entry 15, Table 2), suggesting aliphatic thiol should be stable under the standard condition. Opportunity arises for the synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfides. Different from the symmetrical disulfide, the unsymmetrical one had its inherent challenge in synthesis with high selectivity. But the present protocol could get around the drawback and achieve the synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfide with excellent isolated yield in a more facile and efficient manner when 3.0 equiv. the aliphatic thiol 3 was added into the mixture at the initial stage (Scheme 1). Taking the synthesis of disulfide 4b as a model, this unsymmetrical synthesis occurred smoothly in and disulfide 4b was obtained in 92% isolated after 3 h irradiation. This method was tolerated to various functional groups and influenced slightly by electronic effect (4e, 4j and 4k). Hetero- (4m) and ployaromatic (4n) disulfides were also afforded by this protocol successfully.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Visible light photocatalytic selective aerobic oxidative synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfides by TEMPOa. Reaction conditions: thiol (0.6 mmol), 3 (1.8 mmol), 0.030 mmol of TEMPO (0.03 mmol), 3 W blue LEDs irradiation, EtOH (1 mL), O2 (0.1 MPa). The data below the disulfide molecules are reaction time (h) and isolated yields respectively, see Supporting information for the NMR and HRMS data. | |

After gathering the optimized conditions and affirming the generality for this visible light photocatalytic protocol, the underlying mechanistic insight was elucidated regarding this TEMPO mediated process. For a photocatalytic reaction, it should be wavelength dependent. Thus, we carried out the selective oxidation reaction with different emitting maximum wavelength (λmax). Table S3 (Supporting information) shows that 460 nm blue LEDs (the light-emitting spectrum, Fig. S1 in Supporting information) give the best result, indicating that the absorption of the visible light should be centered around this range.

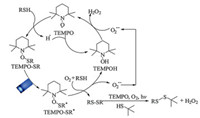

In appearance, TEMPO is red-orange which means that it can directly absorb visible light around 460 nm range. However, absorption of TEMPO disappears in EtOH due to solvatochromism phenomena. Therefore, we assumed that there should be other pivotal species involved to capture visible light. The trapping sulfur radical by TEMPO accounts for the photocatalytic oxidative synthesis of symmetrical disulfide. Some further investigations were performed on the reaction course. During, the optimization of applicable amount of TEMPO, TEMPO was increased to 0.5 equiv. and 0.6 mmol of 4-methylbenzenethiol 1b and 0.3 mmol of TEMPO were combined in a 10 mL Pyrex vessel containing 1 mL of EtOH. Subsequently, O2 was injected into the sealed vessel to reach 0.1 MPa of pressure. Then the reaction mixture was magnetically stirred at 1500 rpm and simultaneously illuminated for 25 min. The reaction pressure was released and the crude product products were purified with column chromatography (petroleum ether: ethyl acetate = 80:1, v:v). then the target products 2b and 5b were obtained (see photocatalytic experiments 3.7 in Supporting information). Complex 5b, formed by from 4-methylbenzenethiol 1b and TEMPO, is reddish which can absorb visible light and can be excited by 460 nm blue LEDs for the activation of O2. We successfully trapped the radical intermediate 5b in 17% isolated yield, together with the product 2b in 81% yield (Eq. S1 in Supporting information). This observation indicated directly the sulfur-centered radical was involved in the visible light-promoted process.

Furthermore, kinetic studies were carried out in an effort to understand the mechanism. As for the synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfide 4b, the concentrations of main components (1b, 2b and 4b) were recorded by GC-FID during the synthesis of 4b. The results were summarized as follows: The product 2b was afforded sharply at the initial 20 min from 1b, then it underwent gentle consumption until it was depleted. Whilst the product 4b began to increase dramatically after the mixture was irradiated for 20 min, and received an excellent yield at the end. From the observations, we concluded that: i) The substrate 1b was more prone to transform into disulfide 2b at the initial stage; ii) the symmetrical disulfide 2b was not stable in the identical reaction conditions with presence of aliphatic thiol 3. And it would be transformed into the unsymmetrical disulfide 4b via a radical pathway motivated by visible light.

Based on the above evidences, a plausible mechanism was proposed for the visible light photocatalytic selective aerobic oxidation of thiols into disulfides by TEMPO (Scheme 2). First, the key intermediate TEMPO-SR was obtained along with the generation of H· after the TEMPO attacked the substrate benzenethiol. The active H· was prone to combine with TEMPO to give TEMPOH. For the newly formed complex TEMPO-SR, it was motivated by visible light to an excited state TEMPO-SR*. Subsequently, the TEMPO-SR* was treated by benzenethiol and O2 to afford the symmetrical disulfide, superoxide anion radical O2·- and TEMPOH. Then, the photocatalytic reaction cycle could be finished after the TEMPOH combined with O2·- to regenerate TEMPO, affording H2O2 as an exclusive byproduct. Moreover, the visible light photocatalytic synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfide includes two sequential reactions. The selective oxidation of benzenethiol into symmetrical disulfide occurred beforehand and aliphatic thiol 3 was intact during this stage. Then, the formed symmetrical disulfide underwent a homolytic cleavage in the presence of TEMPO to react with aliphatic thiol 3, affording the corresponding unsymmetrical disulfides in the end. Meanwhile, O2 acts as an acceptor for proton and electron.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. A plausible mechanism for the selective aerobic oxidation of thiols into disulfides by TEMPO visible light photocatalysis. | |

In summary, we have serendipitously disclosed a visible light promoted protocol for the oxidation thiols into disulfides including symmetrical and unsymmetrical ones by employing TEMPO as photocatalyst at room temperature. Besides, EtOH was selected the solvent and O2 was chosen as the terminal oxidant. Importantly, no additives and transition-metals were needed during the reaction process. A complex in situ formed between thiol and TEMPO has been identified to be central in implementing the photocatalytic activation of O2. This reaction protocol had been identified by a wide scope of thiols, and the results showed excellent yields and functional groups compatibility.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21773173, 21503086), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2042018kf0212) and the start-up fund of Wuhan University.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2019.10.024.

| [1] |

P. Nagy, C.C. Winterbourn, Redox chemistry of biological thiols, in: J.C. Fishbein (Ed.), Advances in Molecular Toxicology, Elsevier B.V., Amsterdam, 2010, pp. 183-222.

|

| [2] |

N.J.W. Straathof, Y.H. Su, V. Hessel, T. Noël, Nat. Protoc. 11 (2016) 10-21. DOI:10.1038/nprot.2015.113 |

| [3] |

A.M. Sauer, A. Schlossbauer, N. Ruthardt, et al., Nano Lett. 10 (2010) 3684-3691. DOI:10.1021/nl102180s |

| [4] |

J.P. Tam, C.R. Wu, W. Liu, J.W. Zhang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113 (1991) 6657-6662. DOI:10.1021/ja00017a044 |

| [5] |

C.D. Spicer, B.G. Davis, Nat. Commun. 5 (2014) 4740. DOI:10.1038/ncomms5740 |

| [6] |

A. Corma, T. Rodenas, M.J. Sabater, Chem. Sci. 3 (2012) 398-404. DOI:10.1039/C1SC00466B |

| [7] |

S. Chen, H.M. Li, P. Hou, Anal. Chim. Acta 993 (2017) 63-70. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2017.09.016 |

| [8] |

R.B. An, P. Wei, D.T. Zhang, N. Su, Tetrahedron Lett. 57 (2016) 3039-3042. DOI:10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.05.107 |

| [9] |

P. Sang, Z.K. Chen, J.W. Zoua, Y.H. Zhang, Green Chem. 15 (2013) 2096-2100. DOI:10.1039/c3gc40724a |

| [10] |

N. Taniguchi, J. Org. Chem. 80 (2015) 1764-1770. DOI:10.1021/jo5026805 |

| [11] |

Z.H. Peng, X. Zheng, Y.J. Zhang, D.L. An, W.R. Dong, Green Chem. 20 (2018) 1760-1764. DOI:10.1039/C8GC00381E |

| [12] |

S.T.A. Shah, K.M. Khan, M. Fecker, W. Voelter, Tetrahedron Lett. 44 (2003) 6789-6791. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(03)01402-3 |

| [13] |

A. Dhakshinamoorthy, S. Navalon, D. Sempere, M. Alvaro, H. Garcia, ChemCatChem 5 (2013) 241-246. DOI:10.1002/cctc.201200569 |

| [14] |

A. Dhakshinamoorthy, M. Alvaro, H. Garcia, Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 46 (2010) 6476-6478. DOI:10.1039/c0cc02210a |

| [15] |

H. Golchoubian, F. Hosseinpoor, Catal. Commun. 8 (2007) 697-700. DOI:10.1016/j.catcom.2006.08.036 |

| [16] |

M. Kirihara, Y. Asai, S. Ogawa, et al., Synthesis (2007) 3286-3289. |

| [17] |

M.H. Ali, M. McDermott, Tetrahedron Lett. 43 (2002) 6271-6273. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)01220-0 |

| [18] |

N.A. Noureldin, M. Caldwell, J. Hendry, D.G. Lee, Synthesis (1998) 1587-1589. |

| [19] |

J.B. Arterburn, M.C. Perry, S.L. Nelson, B.R. Dible, M.S. Holguin, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 (1997) 9309-9310. DOI:10.1021/ja972013r |

| [20] |

B.B. Dong, T.F. Liu, C. Li, F.X. Zhang, Chin. Chem. Lett. 29 (2018) 671-680. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.12.002 |

| [21] |

S. Choi, T. Chatterjee, W.J. Choi, Y. You, E.J. Cho, ACS Catal. 5 (2015) 4796-4802. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.5b00817 |

| [22] |

D. Ravelli, D. Dondi, M. Fagnoni, A. Albini, Chem. Soc. Rev. 38 (2009) 1999-2011. DOI:10.1039/b714786b |

| [23] |

S. Peiris, J. McMurtrie, H.Y. Zhu, Catal. Sci. Technol. 6 (2016) 320-338. DOI:10.1039/C5CY02048D |

| [24] |

W.R. Leow, X.D. Chen, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 92 (2019) 505-510. DOI:10.1246/bcsj.20180274 |

| [25] |

W.R. Leow, J.C. Yu, B. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 9780-9784. DOI:10.1002/anie.201805395 |

| [26] |

M. Oba, K. Tanaka, K. Nishiyama, W. Ando, J. Org. Chem. 76 (2011) 4173-4177. DOI:10.1021/jo200496r |

| [27] |

C. Bottecchia, N. Erdmann, P.M.A. Tijssen, et al., ChemSusChem 9 (2016) 1781-1785. DOI:10.1002/cssc.201600602 |

| [28] |

W.B. Wu, Y.C. Wong, Z.K. Tan, J. Wu, Catal. Sci. Technol. 8 (2018) 4257-4263. DOI:10.1039/C8CY01240G |

| [29] |

X.B. Li, Z.J. Li, Y.J. Gao, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 2085-2089. DOI:10.1002/anie.201310249 |

| [30] |

T. Tankam, K. Poochampa, T. Vilaivan, M. Sukwattanasinitt, S. Wacharasindhu, Tetrahedron 72 (2016) 788-793. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2015.12.036 |

| [31] |

Y.H. Su, A. Talla, V. Hessel, T. Noël, Chem. Eng. Technol. 38 (2015) 1733-1742. DOI:10.1002/ceat.201500376 |

| [32] |

H.M. Hao, Z. Wang, J.L. Shi, X. Li, X.J. Lang, ChemCatChem 10 (2018) 4545-4554. DOI:10.1002/cctc.201801304 |

| [33] |

X.J. Lang, J.C. Zhao, X.D. Chen, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 4697-4700. DOI:10.1002/anie.201600405 |

| [34] |

R.F. Chen, J.L. Shi, Y. Ma, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 6430-6434. DOI:10.1002/anie.201902543 |

2020, Vol. 31

2020, Vol. 31