With the rapid increase in demand for green and clean energy, the progress of intelligent products and electric vehicles worldwide, a variety of energy storage systems are designed and improved. However, many energy storage systems (ESS) including lithium ion battery (LIB), sodium ion battery (SIB), potassium ion battery (PIB), Li-S battery, zinc ion battery (ZIB), supercapacitor are restricted by the essentials of high energy density, high power density, long durability or other drawbacks [1-4]. Therefore, the materials for electrodes with satisfactory properties are urgently-needed.

2D layered materials with strong in-plane covalent bonding and weak out-of-plane van der Waals interaction are like a dawn showing prospects to the ESS. Represented by graphene and transition metal oxides/sulphides, 2D layered materials have already shown great potential due to their unique physical and chemical properties [5]. The layer structure provides extra space for ion insert/extract storage on the basis of large specific surface area. For instance, the anodes of graphene can deliver a high lithium-ion storage capacity of >2000 mAh/g during the first Li+ insertion process [6]. Moreover, the further enlargement of interlayer space by the intercalation of different ions, atoms and molecules can provide better ion-accessible surface, abundant active sites and decrease the ion diffusion energy barrier in ESS. Such strategy has been widely explored to improve the capacity, rate performance, stability and reducing volume expansion indifferent devices. For examples, N-doped carbon monolayers were alternately intercalated into the adjacent MoS2 monolayers via an annealing-followed soft-template approach, the obtained electrodes can deliver a reversible discharge capacity of 1025 mAh/g at 1000 mA/g for LIB [7]. K+ was pre-intercalated into layered birnessite-MnO2 nanoflakes via a one-step facile hydrothermal method during the in-situ fabrication on graphene foam, the foam electrodes show a high pseudocapaitance of 344 F/g at 2 mV/s [8]. Due to the realized significant performance optimization results of graphene and transition metal oxides/sulphides by intercalation, there are several novel methods developed to obtain more achievements, especially the cation intercalations, such as hydrothermal method, immersion method, ion exchange method and electrochemical method [9].

Beyond those materials, MXenes with unique tunable layer structure, rich surface terminations, excellent conductivity and other prominent physicochemical properties have greatly enriched the 2D materials family [10]. Generally, MXenes have a formula of Mn+1XnTx (n = 1, 2, 3) obtained by selective etching A layers from MAX phases, where M represents the early transition metal (such as Ti, V, Mo, Nb and Hf), X represents carbon and/or nitrogen, A represents elements from group IIIA or IVA (such as Al, Ga and Sn) and Tx represents terminal groups derived from the synthesis procedures (such as -O, -F and -Cl) [4, 11]. Based on the distinguishing characteristics, MXenes have attracted lots of attention and been invested in various applications, such as carbon capture to reduce the ever-increasing CO2 emissions [12], terahertz absorption of 3D MXene/GO foam [13], plasmonic photodetection of Mo2CTx in the visible spectral region [14], improved thermal property of Ti3C2/epoxy composite [15], nanofluidic osmotic power generators of MXene/Kevlar nanofiber composite membranes [16] and electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction of P-doped V2CTx MXene [17]. Particularly, MXenes are most widely used in energy storage systems including LIB, SIB, Li-S battery, ZIB, supercapacitor and hybrid devices, benefitting from their excellent conductivity for electronic transmission, large layer spacing for energy storage and easy delamination for flexible electrodes. The theoretical capacitance of Ti3C2 for Li, Na and K can reach to 448 mAh/g, 352 mAh/g and 192 mAh/g, respectively [18]. After composite with CNT or treated by intercalation agents, the MXenes electrodes can deliver highly improved capacity over 1000 mAh/g under 0.1 A/g in LIB [19, 20]. These researches and applications have greatly promoted the essential cognition of MXenes and led another spring in the field of energy storage, among which cation intercalation played a non-negligible effect. The cation intercalation can also tune the lattice structure, electronic structure and coordination environment of different atoms. These changes spur scientists to find powerful and suitable characterizations to precisely study them. Furthermore, the construction of synchrotron radiation sources and development of synchrotron radiation X-ray characterizations have shown high potential on exploring the property, structure and energy storage/conversion mechanism of MXenes and their derivatives [21-23].

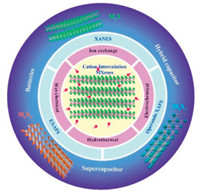

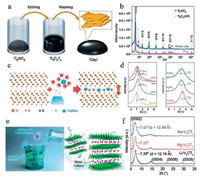

In recent years, there are already many reviews of MXenes focusing on the development of synthesis procedures, properties, theoretical study, delamination, electrochemical energy storage and conversion. However, less review paid the attention on cation intercalation engineeringfor energy storage and the X-ray characterizations of MXenes. Thus, this review aims to summarize the recent works on cation intercalated MXenes via different strategies and the application of X-ray absorption characterizations. First, there is a brief introduction of synthesis methods of MXenes according to the new progresses on fabrication. Then, a variety of most commonly used cation intercalation methods are described. The synchrotronbased X-ray absorption spectroscopic characterizations on cation intercalated MXenes and their operando applications in different ESS are also summarized as shown in Fig. 1. Finally, an outlook is proposed on the future research.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of cation intercalated MXenes via different strategies for energy storage and the synchrotron radiation X-ray characterizations. | |

2. Preparation

As mention above, MXenes are usually obtained from MAX phases by selectively removing the A layers. This is mainly due to the stronger covalent/ionic bonding of M—X compared with metallic bonding of M—A. Due to the different characteristics between M—X and M—A bonds, it is possible to remove "A" layers by proper etchants resulting in specific terminations.

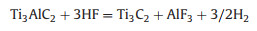

The first and most versatile etching method is HF-etching, reported in 2011. Ti3C2Tx is obtained with typical accordion-like multilayer nanostructure after removing Al layers from densely layer-stacked Ti3AlC2 MAX in HF solution at room temperature. After this, lots of MXenes including M2X, M3X2 and M4X3 are fabricated via HF etching method from their homologous MAX phases. Notably, the etching time, etching temperature, concentration of HF acid and particle size of MAX phases are all pretty essential parameters to get ideal MXenes due to the kinetically controlled etching process described as below:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

Generally, the obtained bulk MXenes can be further delaminated into single or few layers by the intercalation of different agents like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and tetrabutylammoniumhydroxide (TBAOH). Following by conventional sonication and vacuum filtration, the free-standing MXene films are achieved which greatly enriched the usability of MXenes and their composites [24].

Despite the widely operated HF etching method, the toxicity, pollution, high risk and difficulty in operation of HF encourages scientists to find milder and safer etchants. In situ HF method is then developed by combining fluoride salts (LiF, NaF, KF or NH4F) and HCl/H2SO4 [25]. HF acid in the mixed solution can be highly controllable by tuning the concentration of each solution. Compared with HF etching method, this "in situ HF" method can result in larger size and fewer defects of MXene samples with spontaneously intercalation of different cations which bring windfall benefits for subsequent applications. NH4HF2 is also used as another kind of milder etchant which may resulting in more uniform interlayer spacing, larger c lattice parameters according to the intercalation of NH4+ and NH3 in MXenes [26].

Recently, there are several other strategies developed to synthesize fluorine-free MXenes or just to explore novel methods for obtaining MXenes such as hydrothermal in concentrated alkali [27-29], electrochemical etching process [30-32] and element replacement approach by reaction with Lewis acidic molten salts [33]. In 2017, it has been reported that the treatment of Ti3AlC2 with KOH in the presence of a small amount of water under 180 ℃ could promote the extraction of Al layer and result in total delamination of Ti3C2 MXene [27]. Then, in 2018, Li et al. reported that Ti3C2Tx powder with 92 wt% purity can be successfully prepared via a hydrothermal treatment in 27.5 mol/L NaOH at 270 ℃ [28]. The ultra-high temperature and concentration of alkali are not satisfied even though it promotes the fabrication of MXenes. At the same time, Ti3C2Tx Mxene with sizes up to 18.6 mm and high yield (over 90%) of mono- and bilayers is obtained via an efficient fluoride-free etching method based on the anodic corrosion of Ti3AlC2 in the mixture of NH4Cl and tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAOH) [31]. Coincidently, in 2019, Hao et al. reported a universal strategy to successfully synthesize Ti2CTx, Cr2CTx and V2CTx Mxenes based on thermal-assisted electrochemical etching route in HCl electrolyte [32]. In the same year, Huang et al. reported an element replacement approach by reaction with Lewis acidic molten salts to synthesize Ti3C2Cl2 and Ti2CCl2 under 550 ℃ [33]. It is persuasive that these etching approaches will play a crucial factor in future explorations.

3. Cation intercalation of MXenesDue to abundant etching methods, dozens of MXenes are created and applied in various fields, represented by Ti3C2, Ti2C, V2C, Nb2C, Mo2C and Nb4C3. Then a number of agents and methods have been developed to obtain intercalated MXenes in order to improve their interlayer spacing, lattice structure, electronic structure and property. In this section, we will summarize the most widely and sophisticated methods of cation intercalation of MXenes.

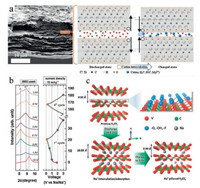

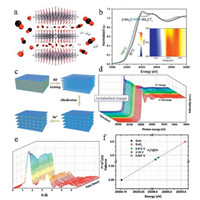

3.1. Wet-chemical intercalationThis method is the most convenient and direct way to realize different cations intercalated into MXene layers. It means that the intercalation is conducted in aqueous or other solutions by adding the solution of target precursors into MXenes under mild temperature. As mentioned before and shown in Fig. 2a, during the etching process of fluoride salts and HCl mixture, different cations will spontaneously intercalated into MXene layers. Li+ is intercalated into Ti3C2Tx MXene during the etching process in LiF/HCl reported by Ghidiu et al. in 2014. The successful intercalation is proved through XRD results in Fig. 2b. The (0002) peaks of Ti3C2Tx MXene and its 'clay' are both at much lower angle than typical MXene produced by HF-etching (green star), showing the obviously enlargement of interlayer spacing for this LiF/HCl etched Ti3C2Tx MXene [34]. As early as 2013, Lukatskaya et al. reported the spontaneous intercalation of cations (Na+, K+, NH4+, Mg2+ and Al3+) from aqueous salt solutions between Ti3C2 MXene layers (the schematic illustration is shown in Fig. 2c). The XRD results (Fig. 2d) show that there is a down shift of (002) peak after placing the Ti3C2Tx invarious salt solutions, indicating the expansion of Ti3C2Tx interlayers due to the cation intercalation [35]. Moreover, Beidaghi et al. reported in 2019 that the delaminated V2CTx (d-V2CTx) MXenes can also be intercalated with cations by immersing in concentrated alkali chloride solutions as shown in Figs. 2e and f. The change in the position of (002) peak after the treatment in Li+, Na+ and Mg2+ solutions indicates the decrease of the interlayer spacing on the type of cation present between the d-V2CTx layers. This is probably caused by the attraction of the MXene layers to the interlayer Li+, Na+ and Mg2+ cations [36]. The cation intercalated MXenes obtained through wet-chemical method get improved physical and electronic structures which are beneficial for the stable structure and tunable properties.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Different types of wet-chemical methods for cation intercalation of MXenes. (a) Simultaneous Li+ intercalation during the etching process of Ti3AlC2 powders in LiF/HCl solution; (b) XRD patterns of Ti3C2Tx, pink trace is for multilayer Ti3C2Tx, the blue trace is for the same sample after rolling into an approximately 40-mm-thick film. (c) Schematic illustration of the intercalation of cations between Ti3C2Tx layers by immersing MXenes in aqueous salt solutions; (d) XRD patterns after placing the Ti3C2Tx in various salt solutions. The dashed vertical line refers to the (002) peak of original Ti3C2Tx MXenes. (e) Schematic illustration of cations intercalate into d-V2CTx MXenes; (f) XRD patterns of various cations intercalated d-V2CTx MXenes. The dashed line on the left of the graph refers to the (002) peak of d-V2CTx before intercalation. (a, b) Reproduced with permission [34]. Copyright 2014, Springer Nature. (c, d) Reproduced with permission [35]. Copyright 2013, American Association for the Advancement of Science. (e, f) Reproduced with permission [36]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. | |

3.2. Electrochemical intercalation

Electrochemical methods mainly come up for the intercalation of assorted cations of various sizes and charges into interlayer spacing of MXenes through electrochemical reactions, such as during the charge/discharge process of supercapacitors, batteries and hybrid capacitors. The unique layered structure of MXenes allows multiple cations in aqueous and organic electrolytes to be embedded via electrochemical intercalation method. Li+, Na+, K+ and Mg2+ can successfully intercalated into Ti3C2Tx paper electrode driven by the electrochemical kinetics in the aqueous electrolyte of Li2SO4, Na2SO4, K2SO4 and MgSO4, respectively.

Interestingly, the insertion of Li+, Na+ and Mg2+ ions results in contraction of the Ti3C2Tx electrode (Fig. 3a), whereas for K+ a small expansion is observed. This is mainly due to the difference of ion radius, terminations on MXene layers and the rearrangement of hydration shell of ions during the intercalation process, which still needs further investigation [37]. Moreover, by simply changing the solvent of the electrolyte such as LiTFSI in DMSO, acetonitrile and propylene carbonate, the interlayer spacing of MXenes will also appear differently during charge/discharge process, which is mainly due to the difference of desolvation during electrochemical process [39]. In batteries systems, cations from reference metal anodes (such as Li, Na and K) can also insert/extract through MXenes interlayer. For instance, V2C MXene was reported to as anode material for Na-ion batteries. The energy storage occurred through Na+ intercalation between the layers of V2CTx proved from the XRD results as shown in Fig. 3b. (002) diffraction peak shifts to lower angle during the first sodiation process, indicating the expansion of MXene interlayer spacing. Moreover, the irreversible expansion/contraction during Na+ intercalation/deintercalation is also observed (Fig. 3c). This mainly attributes to the trapping of Na+ in V2CTx structure, relating to the interaction between Na+ and terminations of MXene layers, as well as the formation of solid electrolyte interphase. Beyond those, electrochemical intercalation has already been widely used or passively occurred in most of the energy storage devices and still showing great appealing to scientists [36, 40-42].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Electrochemical intercalation of cations into MXene layers in EES, such as supercapacitor and batteries. (a) Morphology of the delaminated Ti3C2Tx paper electrode and the schematic representation of the contraction of Ti3C2Tx interlayers during the intercalation of cations. Reproduced with permission [37]. Copyright 2015, Elsevier Ltd. (b) Ex situ XRD patterns (left) for V2CTx MXene electrode during the electrochemical sodiation/desodiation process (right); (c) Schematic illustration of the expansion/contraction behavior of V2CTx during sodiation/desodiation. Reproduced with permission [38]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. | |

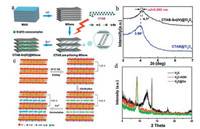

3.3. Ion exchange intercalation

Generally, the ion exchange intercalation in MXenes is based on the different electrostatic interaction between cations in negatively charged MXene interlayers. This can be realized between organic long-chain cations [43], cations [44] as well as between both of them [45]. Fig. 4a illustrates a schematic for ion exchange intercalation between CTA+ and Sn4+. When Ti3C2 is firstly immersed in CTAB solution under 40 ℃, the CTA+ would selfassembled and intercalates into the interlayer of negatively charged Ti3C2 by electrostatic interaction. There is a guess that during the CTA+ intercalation, the CTA+ cations in Ti3C2 interlayers may replace the H+ in the [Ti-O]-H+ to form [Ti-O]-CTA+. The interlayer spacing of CTAB@Ti3C2 is increased to 2.230 nm compared with the original spacing of 0.977 nm for Ti3C2 MXene. After the CTAB@Ti3C2 is immersed in SnCl4 solution, Sn4+ is successfully intercalated into CTAB@Ti3C2 by the ion exchange intercalation with CTA+ cation, which is confirmed by the XRD results in Fig. 4b. The (002) peak of CTAB-Sn(IV)@Ti3C2 shifts to a higher angle, indicating the decrease of interlayer spacing after Sn4+ intercalation, indicating the possible ion exchange between smaller Sn4+ and CTA+ [45]. In 2018, we also reported the ion exchange process between cations in V2C MXene layers [44, 46]. The illustration is shown in Fig. 4c. V2C MXene is firstly intercalated with K+ by immersing in 2 mol/L KOH solution. The interlayer spacing of V2C-KOH MXene increases to 0.963 nm from the original spacing of 0.735 nm for V2C MXene. Then Co2+ can intercalate into the interlayer via ion exchange process by immersing V2C-KOH in C4H6O4Co solution confirmed by XRD results (Fig. 4d) and other characterizations. The higher angle shift of (002) peak of V2C@Co compared with V2C-KOH indicates the ion exchange between K+ and Co2+ mainly due to the difference of electrostatic interactions.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) Schematic illustration of ion exchange intercalation in Ti3C2 MXene between CTA+ and Sn4+; (b) Magnification of XRD patterns of CTAB@Ti3C2 before and after Sn4+ intercalation. (c) Schematic illustration of ion exchange intercalation in V2C MXene between K+ and Co2+; (d) XRD patterns of V2C, V2C-KOH and V2C@Co MXenes. (a, b) Reproduced with permission [45]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (c, d) Reproduced with permission [44]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. | |

3.4. Hydrothermal intercalation

This is another method to realize cation interaction especially in preparing MXenes quantum dots and high-purity Ti3C2Tx (T = OH, O), cation intercalation process is conducted during the hydrothermal reaction [27-29, 47, 48]. For instance, monolayered Ti3C2 quantum dots (MQDs) decorated with –NH groups can be prepared through a facile hydrothermal method. The morphologies of MQDs are adjustable by changing the reaction temperature. The MQDs obtained under 100 ℃ exhibits the pristine structure of MXene due to the low reaction temperature, its (0002) peak also shifts to lower angle compared with the untreated Ti3C2Tx mainly due to the intercalation of cations [47]. The hydrothermal etching method in concentrated solution of alkali can also result in the intercalation of cation intercalation like Na+ and K+. As reported, Ti3C2Tx powder with high purity can be successfully prepared via a 27.5 mol/L NaOH treatment at 270 ℃ with the intercalation of Na+ [28, 48].

Besides of the above discussion, cation intercalation can also be achieved in ionic liquid. In 2016, Simon et al. reported that MXene materials was investigated in 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide (EMI-TFSI) ionic electrolyte for supercapacitor for the first time. It was found that the interlayer spacing changes with the intercalation and de-intercalation of EMI+ cations and/or TFSI- anions [49, 50]. The intercalation of cations in ionic liquid is further performed by other works on MXenes to improve the supercapacitor property [51, 52]. As a preliminary summary, the numerous intercalators can tune the properties of MXenes via different intercalation strategies, enabling more comprehensive exploration and wider applications of 2D MXenes.

4. Synchrotron radiation X-ray absorption spectroscopic characterizations of cation intercalated MXenesFurther development of new and improved nanomaterials like 2D MXenes require the ability to control their structure at nanoscale and thorough comprehension of their properties in electronic level. In order to achieve controllable synthesis of MXenes and study their physicochemical properties, advanced characterization methods are essential. The synchrotron-based Xray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) with short-range order sensitivity make it a prominent characterization in probing the local structural environment of atoms and electronic structure of MXenes, as well as detecting their dynamic process in various reactions [21, 53].

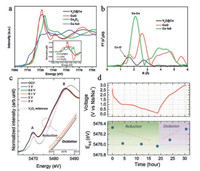

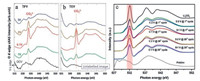

4.1. Ex-situ X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS)The X-ray absorption near edgestructure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) have shown very prominent advantages in exploring the structure of cation intercalated MXenes. In the case of cobalt ion engineered interlayers of V2C MXene (V2C@Co) for superior Li+ storage, we deeply studied the local structure of cobalt ion in V2C MXene combined XANES, EXAFS and other characterizations (Figs. 5a and b). Particularly, two different Co-O bonds are fitted with bond length of 2.09 Å and 1.92 Å according to different oxidation state of Co. In fact, the combination of V-O-Co bonding is clearly verified in V2C@Co MXene and the average chemical valence of Co atoms is also confirmed to be +2.12 [44]. In 2017, Yang et al. reported the study of Na+ charge storage mechanism in V2CTx MXene using ex-situ XAFS (Figs. 5c and d). The V K-edge XANES results clearly showed the redox reaction of vanadium during the Na+ intercalation/deintercalation, proving that the redox reaction of transition metal in MXenes should be responsible for the electrochemical charge storage [38]. When Ti3C2Tx MXene was used as supercapacitor electrode in H2SO4 electrolyte, K-edge XANES can be used to study the oxidation state changes of Ti during energy storage process, proving the pseudocapacitive behavior in this system [23]. Actually, ex-situ XAFS also plays a very prominent role in studying the material structure on other fields, i.e., MXenes composite and single atom catalyst for Zn-air battery and water splitting, etc. [22, 54].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) Normalized XANES spectra of Co K-edge. Inset: First-order derivative of normalized XANES spectra; (b) Fourier-transformed Co K-edge EXAFS spectra for V2C@Co, CoO and Co foil. (c) Ex-situ V K-edge XANES spectra of V2CTx at different voltages during first sodiation/desodiation process; (d) Corresponding voltage profile and variation of V absorption edge energy at half height of normalized XANES spectra. (a, b) Reproduced with permission [44]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. (c, d) Reproduced with permission [38]. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH. | |

4.2. Soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy

This technique is powerful in elucidating the electronic and structure of molecules on surfaces, especially for absorbed elements with comparable low Z values. The K-edge spectrum of 2p (such as O, C and N), L-edge spectrum of 3p (such as S and P) non-metal elements and 3d transition metal elements (such as Ti, V, Mn and Co) can be considered as an image of the 2p and 3d unoccupied density of states [55]. These results are very sensitive to the local structure of the transition metal oxides which is ideal characterizations for MXenes.

In 2016, Magne et al. evidenced the role of surface groups in the chemical bonding in Ti3C2Tx MXene. Benefiting from the C K-edge XANES, they concluded that the multilayer Ti3C2Tx are predominantly functionalized with OH and F groups and the etchant has little effect on the electronic structure of the MXenes but changes significantly the [O]/[F] ratio [56]. The ex situ of O K-edge XAS results (Figs. 6a and b, the work of Yang et al.) collected under TFY and TEY both show the reversible formation/decomposition of CO32- species upon the (de)intercalation of Na+ in V2CTx MXene. It is speculated that the reaction occurred between the Na+ intercalated V2CTx and the nonaqueous electrolyte. However, this CO32- related reaction still needs further understanding [38]. In 2018, our group also found the reversible reaction of CO32- species during cycling process when Sn4+ intercalated V2C MXene was used in LIB (Fig. 6c). It could be related to the electrochemical reaction between oxygen on V2C layers and the EC/DMD electrolyte which may contributes to the Li+ storage capacity [44]. For this technique, the request of high vacuum and slow data acquisition rate still hinder the development of soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Even though, we believe this characterization will become an imperative method in 2D materials with the increase of energy and time resolution of the components.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. (a, b) Bulk-sensitive TFY and surface-sensitive TEY of O K-edge soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy at different voltages of V2CTx for SIB, respectively. Reproduced with permission [38]. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH. (c) O K-edge soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy of V2C@Sn electrode under different voltages for LIB. Reproduced with permission [44]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. | |

4.3. In-situ XAFS

In addition to the static XAFS characterization of MXenes summarized above, in-situ XAFS characterization managed during dynamic reaction process is expected to provide more reliable and fine information for understanding the dynamic mechanism in 2D materials including MXenes. For instance, in-situ XANES was performed to study the structural stability of 2D Mo2CTx temperature-programmed reduction in reducing atmosphere (Fig. 7a), reported by Deeva et al. in 2019. From XRD and thermo-gravimetric analysis, when the temperature is below 350 ℃ in H2, the residues of water trapped in between carbide layers are desorbed. With the increase of temperature especially to 500 ℃ and 600 ℃, the functional groups are defunctionalized from the surface, leading to a decrease of interlayer distance. In-situ XANES of Mo K-edge is further performed in the same in situ experiment (Fig. 7b). With the increase of temperature, the edge position of Mo XANES spectra shifts continuously to lower energies, indicating the gradual decrease of oxidation state of Mo. A fast transformation of Mo2CTx to a new phase is also observed around 600 ℃, indicating the forming of bulk β-Mo2C [57].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. (a) Schematic illustration of 2D Mo2CTx remaining stable in a reducing environment under high temperature up to 550–600 ℃; (b) In-situ Mo K-edge XANES study of Mo2CTx under temperature-programmed reduction in H2. (c) Fabrication process of Sn4+ intercalated V2C MXene via ion exchange method; (d) In situ Sn K-edge XAFS spectra during Li+ storage process of V2C@Sn as electrode in LIB; (e) Fourier-transformed Sn K-edge EXAFS spectra corresponding to (d); (f) Average chemical valence of Sn atom in V2C@Sn at applied potentials, using the Sn K-edge absorption edge energy of the reference SnO and SnO2. (a, b) Reproduced with permission [57]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (c–f) Reproduced with permission [46]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. | |

In 2018, our team reported the operando XAFS characterization on studying the dynamic Li+ storage mechanism in Sn4+ intercalated V2C MXene (Fig. 7c) in LIB. The in-situ Sn K-edge spectra during cycling process under corresponding voltages are collected to probe the changes of Sn chemical state (Fig. 7d). During the first few cycling, the intensity of the main absorption peaks and position of absorption edges for Sn K-edge spectra gradually changes, as well as the coordination numbers of Sn (Fig. 7e). These results indicate the changes of oxidation state of Sn during the embedding and extraction of Li+ in V2C layers. Furthermore, we calculate the average valences of Sn at almost fully discharge and charge state when the cycling process is stable (Fig. 7f). As a result, the average valences of Sn reversibly changes between +3.35 to +3.42 during Li+ deintercalation and intercalation processes. In-situ XAFS measurement is also used to detect the changes in the Ti oxidation state during cycling of Ti3C2Tx in H2SO4 electrolyte for supercapacitor [58]. It proves that the electrochemical behavior of Ti3C2Tx in sulfuric acid is predominantly pseudocapacitive which is in consistent with the above results [23].

5. Cation intercalated MXenes for energy storage 5.1. BatteriesAs an essential energy storage device with high energy density, batteries are widely used as power sources in electronics and electric vehicles. MXenes with unique layer structure for metal ion intercalation storage and high electrical conductivity have been predicted to be promising anode electrode materials for batteries. By using first-principles density functional calculations, Shenoy et al. calculated the capacities for Li, Na, K and Ca on Ti3C2, resulting in 447.8, 351.8, 191.8 and 319.8 mAh/g, respectively [18]. Although the capacity of MXenes for Li is close to that of commercial graphite electrodes in LIB, MXenes exhibit much better rate performance due to smaller diffusion barrier for Li atoms on Ti3C2 (0.07 eV) [59], showing promise in increasing overall battery performance.

It was also found that MXenes with low formula weights, such as Ti2C, Nb2C, V2C and Sc2C show higher gravimetric capacities than their M3X2 and M4X3 counterparts, due to the ion intercalation mechanism. Yao et al. reported the study of electronic properties and Li storage capability of V2C via first-principles calculations. They found that bare V2C monolayer shows fast Li diffusion with low diffusion barrier height and a high theoretical value about 940 mAh/g. However, the functional groups produced in the synthesis process on MXenes surface show important impact on the storage performance. The –F and –OH on the surface tend to block Li diffusion and reduce the Li storage capacity. The calculated theoretical specific capacities for V2CF2 and V2C(OH)2 are just 116 mAh/g and 181 mAh/g [60]. It is also proved that the –O surface termination tends to promote the highest capacity than –F and –OH, whereas termination of –F and/or -OH should be avoided as much as possible [61]. Besides the influence of terminations on capacity, the engineering of interlayer spacing via cation intercalation and MXenes composites can also greatly affect the performance of batteries [19, 62]. For instance, Sn-intercalated V2C MXene electrode can deliver a highly improved discharge capacity of 1284.6 mAh/g with a charge capacity of 1115.6 mAh/g at 0.1 A/g in LIB, which is much higher than the V2C MXene electrode [46].

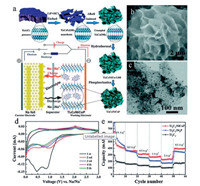

MXenes can also be used in other batteries through metallic ions intercalation, such as Na+ and K+ with similar storage mechanism of LIB. For instance, Yin et al. reported the composite of NiCoP and Ti3C2 as anodes for high-performance SIB in 2019. The synthesis process of the Ti3C2/NiCoP hybrid is shown in Fig. 8a. Li+ can intercalates between Ti3C2Tx layer during the etching of LiF/HCl. Then, during the induce of NaOH, Na+ can intercalates in the interlayer of Ti3C2Tx and replaces Li+, resulting in the crinkle and larger interlayer spacing of Ti3C2Tx. The morphology of final Ti3C2/NiCoP is shown in Figs. 8b and c, indicating the uniform distribution of NiCoP on crumpled Ti3C2Tx. The two broad peaks in CV curves around 1 V and 2 V during cathodic and anodic scans attribute to the insertion and extraction of Na+, also indicating the pseudocapacitance behavior (Fig. 8d). The Ti3C2/NiCoP composite demonstrates a high Na+ capacity of 416.9 mAh/g at 0.1 A/g and excellent rate capability due to the enhanced stability of Co-P bond during the Na+ insertion/extraction [63]. Moreover, MXenes are good candidates beyond the above batteries, such as Li-S battery [64, 65] and ZIB [66, 67].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 8. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthesis process of the Ti3C2/NiCoP hybrid and schematic mechanism of half-cells for SIB; (b, c) Morphology and TEM image of Ti3C2/NiCoP hybrid; (d) CV curves of Ti3C2/NiCoP hybrid electrode in half-cell by using sodium metal as a counter electrode; (e) Rate capability of the Ti3C2, Ti3C2/Ni2P and Ti3C2/NiCoP electrodes. Reproduced with permission [63]. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

5.2. Supercapacitors

MXenes have been also widely used in supercapacitors due to the good electrical conductivity, abundant surface terminations and easy delamination. However, due to the easy oxidation at positive potential, MXenes have mainly been used as the negative electrode in supercapacitors. Additive-free Ti3C2Tx paper in KOH electrolyte shows high volumetric capacitance of 340 F/cm3, which is much higher than activated graphene and other carbon electrodes. Moreover, both bulk MXenes and multi-layered exfoliated MXenes can be intercalated by various cations with various charges and sizes in aqueous electrolytes [35]. The delamination of MXene can further improve the capacity of MXene electrodes due to the increase of interlayer spacing and specific surface area. Beidaghi et al. proved the cation intercalation storage mechanism of V2CTx in various sulfate electrolytes, like Na2SO4, MgSO4 and K2SO4. The Na-V2CTx in 3 mol/L H2SO4 electrolyte shows a high specific capacitance about 1315 F/cm3 and 420 F/g at a scan rate of 5 mV/s due to pseudocapacitive behavior. Under the same scan rate, high volumetric capacitances of 852 and 790 F/cm3 are also achieved in ZnSO4 and K2SO4 electrolytes [36].

The pseudocapacitive behavior of MXenes electrodes in H2SO4 electrolyte is already proved by using in situ Raman (Fig. 9a). During the charging/discharging process, the Raman peaks especially the mode in the range of 530-770 cm-1 shift dramatically. The 590 cm-1 band in Ti3C2O2 is variable, however, the modes at 630 and 672 cm-1 in Ti3C2(OH)2 stay unchanged. It is finally found that hydronium in the H2SO4 electrolyte is involved in bonding with the termination of O in the Ti3C2Tx upon discharging. The bonding/debonding of hydronium also changes the valence state of Ti, resulting in pseudocapacity in acidic electrolyte [68]. The capacity and rate performance of MXenes electrodes can also be increased by preparation of MXene hydrogels and macroporous electrodes (Figs. 9b and c). The prepared MXene hydrogel electrode can deliver a high volumetric capacitance about 1500 F/cm3, and the macroporous electrode shows an excellent rate performance (Fig. 9d). Meanwhile, in the result of EIS, there is an obvious increase of the 45-degree linear part at -0.7 V, -0.9 V and -1.1 V (Fig. 9e), showing the pseudocapacitive mechanism which is in consistent with the redox peaks in CV curves. Based on the mechanism, composites of MXenes and the engineering of functional groups, interlayers of MXenes can be effective methods for preparing high performance supercapacitor electrodes [11, 70]. Recently, the pseudocapacitive performance of dozens MXenes were simulated in aqueous H2SO4 electrolyte by De-En Jiang in 2019. They found that the nitride MXenes exhibit better pseudocapacitive performance than carbide MXenes. This depends on the higher hydrogen adsorption free energy and low shift in the potential at the point of zero charge which can be applied to the design of pseudocapacitive MXene electrodes in future [71].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 9. (a) Schematic of Ti3C2Tx and the Raman analysis for the mechanism study of Ti3C2Tx electrode in H2SO4 electrolyte; (b) Schematic of the structure of MXene; (c) Crosssection of Ti3C2Tx hydrogel and macroporous templated Ti3C2Tx film electrode; (d) CV curves of macroporous Ti3C2Tx film electrode under different scan rates in H2SO4 electrolyte; (e) EIS results collected at different potentials for macroporous Ti3C2Tx film electrode. (a) Reproduced with permission [68]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (b–e) Reproduced with permission [69]. Copyright 2017, Springer Nature. | |

5.3. Hybrid capacitors

This kind of ESS is expected to combine the advantages of both batteries with high energy density and supercapacitors with high powder density and durability. It is a hybrid system with batterytype materials as anode and capacitor-type cathode in nonaqueous electrolyte. During charging process, the hybrid capacitor stores energy through a diffusion-controlled electrochemical process in cathode and a surface-controlled electrochemical process in anode simultaneously. For battery-type materials, extrinsic pseudocapacitance behaviour is receiving attention and playing an important role [72]. Based on the large specific surface area and intercalation pseudocapacitive mechanism, MXenes are widely used in batteries and supercapacitors. Thus, MXenes electrodes can be used for both cathode and anode in hybrid capacitors which is different compared with the discussion in section 5.2. In 2014, Yamada et al. reported the application of Naion hybrid capacitor by using Ti2C as anode with intercalation pseudocapacity and alluaudite Na2Fe2(SO4)3 as cathode. This device operates a high voltage of 2.4 V and delivers 90 mA h/g at 1 A/g indicating the prospect of MXenes for hybrid capacitors [73]. In 2015, Simon et al. reported the V2CTx MXene as positive electrode for Na-ion capacitor. During the pre-intercalation of sodium in MXene and hard carbon electrodes, they are assembled into a hybrid capacitor. This V2CTx/HC hybrid Na+ capacitor shows a high cell voltage of 3.5 V and a capacity of 50 mAh/g based on the intercalation of Na+ into V2CTx layers. The composite of MXenes and cation intercalated MXenes are also reported to fabricate hybrid Li+/Na+/K+ capacitors with excellent property [42, 44, 74-77].

6. Conclusions and outlookIn summary, we make an overview on the cation intercalated MXenes through different strategies, showing that cation intercalation is very important and indispensable on the development of MXenes. The characterization methods to analyse the structure and property of MXenes after cation intercalation with the help of ex/in-situ XAFS are also summarized as well as the application of MXenes in ESS.

Nowadays, more and more MXenes are being discovered and studied, greatly enrich the 2D material family. However, the correspondence of the engineering of MXene structure, surface functionalization and MXene based composite with the performance should be further investigated. Such as we mentioned above, the mechanism of cation intercalated MXene in energy storage and conversion should be better understood. More stable MXenes and efficient synthetic method should be deeply investigated. The fabrication of hybrid capacitor, efficient matching of positive/negative electrodes still needs further exploration. Though X-ray absorption spectroscopic characterizations have shown excellent prospect in studying the local and electronic structures of functional MXene materials, more synchrotron-based X-ray characterizations should be developed and applied including operando and real condition ways. Moreover, synchrotron-based techniques also need to be developed from the aspects of spatial, time and energy resolutions in order to solve the current challenges. Therefore, there is still lots of efforts in promoting the further development of MXenes, and we believe that MXenes will shine in numerous fields in coming future.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was financially supported in part by National Key R & D Program of China (No. 2017YFA0303500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Nos. U1932201, 11574280, 21727801, 11605201), Innovative Research Groups of NSFC (No. 11621063), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. WK2310000074), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 1708085QB27), National Natural Science Foundation of China and Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Italy (NSFC-MAECI, No. 51861135202), CAS Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences (No. QYZDB-SSWSLH018), CAS Iterdisciplinary Innovation Team and National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (No. BX20190315). L. Song acknowledges the support from Key Laboratory of Advanced Energy Materials Chemistry (Ministry of Education), Nankai University (111 project, No. B12015). We thank the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (14W1, SSRF), the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (1W1B and soft-X-ray endstation, BSRF), the Hefei Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ARPES, MCD and Photoemission Endstations at NSRL), and the USTC Center for Micro and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication for helps in characterizations.

| [1] |

A.R. Dehghani-Sanij, E. Tharumalingam, M.B. Dusseault, R. Fraser, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 104 (2019) 192-208. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.023 |

| [2] |

T. Kim, W.T. Song, D.Y. Son, L.K. Ono, Y.B. Qi, J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 2942-2964. DOI:10.1039/C8TA10513H |

| [3] |

J. Ming, J. Guo, C. Xia, W. Wang, H.N. Alshareef, Mater. Sci. Eng. R 135 (2019) 58-84. DOI:10.1016/j.mser.2018.10.002 |

| [4] |

J. Nan, X. Guo, J. Xiao, et al., Small (2019) e1902085. DOI:10.1002/smll.201902085 |

| [5] |

J. Huang, Z. Wei, J. Liao, et al., J. Energy Chem. 33 (2019) 100-124. DOI:10.1016/j.jechem.2018.09.001 |

| [6] |

R. Raccichini, A. Varzi, S. Passerini, B. Scrosati, Nat. Mater. 14 (2015) 271-279. DOI:10.1038/nmat4170 |

| [7] |

L.Y. Jing, G. Lian, F. Niu, et al., Nano Energy 51 (2018) 546-555. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.06.084 |

| [8] |

L.L. Cao, B.Z. Yu, T. Cheng, et al., Ceram. Int. 43 (2017) 14897-14904. DOI:10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.08.006 |

| [9] |

J. Wan, S.D. Lacey, J. Dai, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 45 (2016) 6742-6765. DOI:10.1039/C5CS00758E |

| [10] |

M. Naguib, M. Kurtoglu, V. Presser, et al., Adv. Mater. 23 (2011) 4248-4253. DOI:10.1002/adma.201102306 |

| [11] |

H. Yu, Y. Wang, Y. Jing, et al., Small (2019) e1901503. |

| [12] |

I. Persson, J. Halim, H. Lind, et al., Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) e1805472. DOI:10.1002/adma.201805472 |

| [13] |

W. Ma, H. Chen, S. Hou, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11 (2019) 25369-25377. DOI:10.1021/acsami.9b03406 |

| [14] |

D.B. Velusamy, J.K. El-Demellawi, A.M. El-Zohry, et al., Adv. Mater. (2019) e1807658. DOI:10.1002/adma.201807658 |

| [15] |

R. Kang, Z. Zhang, L. Guo, et al., Sci. Rep. 9 (2019) 9135. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-45664-4 |

| [16] |

Z. Zhang, S. Yang, P. Zhang, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 2920. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-10885-8 |

| [17] |

Y. Yoon, A.P. Tiwari, M. Choi, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. (2019) 1903443. |

| [18] |

D. Er, J. Li, M. Naguib, Y. Gogotsi, V.B. Shenoy, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6 (2014) 11173-11179. DOI:10.1021/am501144q |

| [19] |

J. Luo, X. Tao, J. Zhang, et al., ACS Nano 10 (2016) 2491-2499. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.5b07333 |

| [20] |

X. Wu, Z. Wang, M. Yu, L. Xiu, J. Qiu, Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1607017. DOI:10.1002/adma.201607017 |

| [21] |

V.M. Hong Ng, H. Huang, K. Zhou, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 5 (2017) 3039-3068. DOI:10.1039/C6TA06772G |

| [22] |

Z. Li, L. Yu, C. Milligan, et al., Nat. Commun. 9 (2018) 5258. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-07502-5 |

| [23] |

C. Zhan, M. Naguib, M. Lukatskaya, et al., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9 (2018) 1223-1228. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b00200 |

| [24] |

L. Verger, V. Natu, M. Carey, M.W. Barsoum, Trend. Chem. (2019), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.trechm.2019.04.006.

|

| [25] |

A. Lipatov, M. Alhabeb, M.R. Lukatskaya, et al., Adv. Electron. Mater. 2 (2016) 1600255. DOI:10.1002/aelm.201600255 |

| [26] |

J. Halim, M.R. Lukatskaya, K.M. Cook, et al., Chem. Mater. 26 (2014) 2374-2381. DOI:10.1021/cm500641a |

| [27] |

G. Li, L. Tan, Y. Zhang, B. Wu, L. Li, Langmuir 33 (2017) 9000-9006. DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01339 |

| [28] |

T. Li, L. Yao, Q. Liu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 6115-6119. DOI:10.1002/anie.201800887 |

| [29] |

B. Zhang, J.F. Zhu, P. Shi, W.L. Wu, F. Wang, Ceram. Int. 45 (2019) 8395-8405. DOI:10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.01.148 |

| [30] |

L.G.B. Camargo, B.G. Palazzo, G. Taylor, et al., J. Electrochem. Soc. 162 (2015) H811-H815. DOI:10.1149/2.0031512jes |

| [31] |

S. Yang, P. Zhang, F. Wang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 15491-15495. DOI:10.1002/anie.201809662 |

| [32] |

S.Y. Pang, Y.T. Wong, S. Yuan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 9610-9616. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b02578 |

| [33] |

M. Li, J. Lu, K. Luo, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 4730-4737. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b00574 |

| [34] |

M. Ghidiu, M.R. Lukatskaya, M.Q. Zhao, Y. Gogotsi, M.W. Barsoum, Nature 516 (2014) 78-81. DOI:10.1038/nature13970 |

| [35] |

M.R. Lukatskaya, O. Mashtalir, C.E. Ren, et al., Science 341 (2013) 1502-1505. DOI:10.1126/science.1241488 |

| [36] |

A. VahidMohammadi, M. Mojtabavi, N.M. Caffrey, M. Wanunu, M. Beidaghi, Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) e1806931. DOI:10.1002/adma.201806931 |

| [37] |

J. Come, J.M. Black, M.R. Lukatskaya, et al., Nano Energy 17 (2015) 27-35. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2015.07.028 |

| [38] |

S.M. Bak, R.M. Qiao, W.L. Yang, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 7 (2017) 1700959. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201700959 |

| [39] |

X. Wang, T.S. Mathis, K. Li, et al., Nat. Energy 4 (2019) 241-248. DOI:10.1038/s41560-019-0339-9 |

| [40] |

R.F. Cheng, T. Hu, H. Zhang, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 123 (2019) 1099-1109. |

| [41] |

K. Kim, Y. Ando, A. Sugahara, et al., Chem. Mater. 31 (2019) 5190-5196. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b01334 |

| [42] |

F. Ming, H. Liang, W. Zhang, et al., Nano Energy 62 (2019) 853-860. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.06.013 |

| [43] |

L. Shen, X.Y. Zhou, X.L. Zhang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 6 (2018) 23513-23520. DOI:10.1039/C8TA09600G |

| [44] |

C. Wang, H. Xie, S. Chen, et al., Adv. Mater. 30 (2018) e1802525. DOI:10.1002/adma.201802525 |

| [45] |

J. Luo, W. Zhang, H. Yuan, et al., ACS Nano 11 (2017) 2459-2469. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.6b07668 |

| [46] |

C.D. Wang, S.M. Chen, H. Xie, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 9 (2019) 1802977. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201802977 |

| [47] |

Q. Xue, H. Zhang, M. Zhu, et al., Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1604847. DOI:10.1002/adma.201604847 |

| [48] |

L. Huang, T. Li, Q. Liu, J. Gu, Electrochem. Commun. 104 (2019) 106472. DOI:10.1016/j.elecom.2019.05.021 |

| [49] |

Z. Lin, P. Rozier, B. Duployer, et al., Electrochem. Commun. 72 (2016) 50-53. DOI:10.1016/j.elecom.2016.08.023 |

| [50] |

Z.F. Lin, D. Barbara, P.L. Taberna, et al., J. Power Sources 326 (2016) 575-579. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.04.035 |

| [51] |

S. Chen, Y. Xiang, M.K. Banks., et al., Nanoscale 10 (2018) 20043-20052. DOI:10.1039/C8NR05760E |

| [52] |

S.H. Zheng, C. Zhang, F. Zhou, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 9478-9485. DOI:10.1039/C9TA02190F |

| [53] |

J. Pang, R.G. Mendes, A. Bachmatiuk, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 48 (2019) 72-133. DOI:10.1039/C8CS00324F |

| [54] |

T.Y. Ma, J.L. Cao, M.J. Roniec, S.Z. Qiao, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 1138-1142. DOI:10.1002/anie.201509758 |

| [55] |

J.G. Chen, Surf. Sci. Rep. 30 (1997) 1-152. DOI:10.1016/S0167-5729(97)00011-3 |

| [56] |

D. Magne, V. Mauchamp, S. Celerier, P. Chartier, T. Cabioc'h, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18 (2016) 30946-30953. DOI:10.1039/C6CP05985F |

| [57] |

E.B. Deeva, A. Kurlov, P.M. Abdala, et al., Chem. Mater. 31 (2019) 4505-4513. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b01105 |

| [58] |

M.R. Lukatskaya, S.M. Bak, X.Q. Yu, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 5 (2015) 1500589. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201500589 |

| [59] |

Q. Tang, Z. Zhou, P. Shen, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134 (2012) 16909-16916. DOI:10.1021/ja308463r |

| [60] |

J. Hu, B. Xu, C. Ouyang, S.A. Yang, Y. Yao, J. Phy. Chem. C 118 (2014) 24274-24281. DOI:10.1021/jp507336x |

| [61] |

C. Eames, M.S. Islam, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 16270-16276. DOI:10.1021/ja508154e |

| [62] |

Y. Huang, H. Yang, Y. Zhang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 11250-11256. DOI:10.1039/C9TA02037C |

| [63] |

D.Y. Zhao, R.Z. Zhao, S.H. Dong, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 12 (2019) 2422-2432. DOI:10.1039/C9EE00308H |

| [64] |

L. Jiao, C. Zhang, C. Geng, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 9 (2019) 1900219. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201900219 |

| [65] |

H. Tang, W. Li, L. Pan, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. (2019) 1901907. |

| [66] |

S. Luo, L. Xie, F. Han, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. (2019) 1901336. |

| [67] |

Q. Yang, Z. Huang, X. Li, et al., ACS Nano 13 (2019) 8275-8283. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.9b03650 |

| [68] |

M. Hu, Z. Li, T. Hu, et al., ACS Nano 10 (2016) 11344-11350. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.6b06597 |

| [69] |

M.R. Lukatskaya, S. Kota, Z.F. Lin, et al., Nat. Energy 2 (2017) 17105. DOI:10.1038/nenergy.2017.105 |

| [70] |

Y. Dall'Agnese, M.R. Lukatskaya, K.M. Cook, et al., Electrochem. Commun. 48 (2014) 118-122. DOI:10.1016/j.elecom.2014.09.002 |

| [71] |

C. Zhan, W. Sun, P.R.C. Kent, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 123 (2018) 315-321. |

| [72] |

D. Tie, S. Huang, J. Wang, et al., Energy Storage Mater. 21 (2019) 22-40. DOI:10.1016/j.ensm.2018.12.018 |

| [73] |

X. Wang, S. Kajiyama, H. Iinuma, et al., Nat. Commun. 6 (2015) 6544. DOI:10.1038/ncomms7544 |

| [74] |

P. Yu, G. Cao, S. Yi, et al., Nanoscale 10 (2018) 5906-5913. DOI:10.1039/C8NR00380G |

| [75] |

O. Mashtalir, M.R. Lukatskaya, M.Q. Zhao, M.W. Barsoum, Y. Gogotsi, Adv. Mater. 27 (2015) 3501-3506. DOI:10.1002/adma.201500604 |

| [76] |

A. Byeon, A.M. Glushenkov, B. Anasori, et al., J. Power Sources 326 (2016) 686-694. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.03.066 |

| [77] |

J. Luo, C. Fang, C. Jin, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 6 (2018) 7794-7806. DOI:10.1039/C8TA02068J |

2020, Vol. 31

2020, Vol. 31