MXenes, new transition metal carbide, nitride and carbonitride two-dimensional crystals expressed as Mn+1XnTx (M represents an early transition metal such as Ti, V, Nb or Mo, X stands for carbide, nitride or carbonitride, T represents the active functional groups such as —OH, —O, —F on their surface), have become popular rookies for their good electrical conductivity, large specific surface area, excellent energy storage performance. The first of MXene, Ti3C2Tx, was achieved by using HF etched and extracted Al layers from MAX (A usually represents the third and fourth main group chemical element) based on the weaker bond energy of M-Al than M—C in 2011 by Professors Gogotsi and Barsoum [1, 2]. It is predicted that there may be more than 256 MXenes through the different combinations between M, T and X subsequently, in which Ti3C2Tx is the most studied one [3].

However, similar to graphene and many other two-dimensional materials, except the in-plane covalent bonds, MXenes also have van der Waals interactions between adjacent sheets, which make MXenes narrow interlayer distance and serious aggregation, restrict their practical application severely [4-6]. Hence, opening the interlayer space to obtain larger available surface area, more active sites and wider ion transport channels is critical for achieving materials with improved properties [7]. To this end, several strategies have been used such as converting the MXene flakes into hollow spheres by template method [8, 9], obtaining the three dimensional porous structure composed of interconnected MXene nanoribbons by alkali treatment [10] or aligning MXene sheets vertically through mechanical shearing [11]. Nonetheless, as the increasing requirement for performance, single material could not meet the demand. The design and construction of composites by making use of various materials with complementary and synergistic impact on the structure and performance are highly desired.

In 2013, Gogotsi and Barsoum successfully expanded the interlayer spacing of multi-layers MXenes by large organic molecules such as hydrazine and urea, obtained single-layer or few-layer MXene flakes through subsequent sonication in water [12]. Later, the same research group used LiF and HCl as mild etching agents instead of HF, the obtained Ti3C2 sheets have higher volumetric capacitances attributed to the intercalation of Li+ [13]. In addition, there are many other materials can be used as intercalators, such as cation, dimethyl sulfoxide, N, N-dimethylformamide, isopropylamine and organic alkali [14-16].

This method has gradually developed into the preparation of intercalated MXene-based layered composites (IMLCs) with these advantages: ⅰ) prevents MXenes from stacking, expands the interlayer space and exposes more active sites; ⅱ) combines the advantages of MXenes and other materials, further improves the performance in application; ⅲ) enhances the stability of the composites by fixing other materials between layers of MXenes; ⅳ) the IMLCs are easy to be processed into films with layered structure, which has great potential in the fields of self-supporting electrodes and flexible wearable devices [17, 18].

With the flourishing development of MXenes, many reviews have been reported. Nevertheless, most of the reviews are focusing on the preparation of MXenes and their application in a specific field, there are few reviews focusing on the construction of composites thoroughly. Furthermore, as the most widely used and universal strategy, review article focusing on the construction of IMLCs to improving the overall performance in application has not been found. Hence, in this paper, we classify the strategies of preparing IMLCs firstly and summarize their advantages in enhancing performance in various applications in detail secondly. Finally, we outline the challenges and development prospects of IMLCs, hoping that this review can promotes the deeper application of MXenes.

2. Preparation strategiesUnderstanding the interfacial interactions between different components is essential for constructing hybrid structures and expanding the scope of application. In general, the interactions between MXenes and other materials can be divided into two categories: physical and chemical interactions. Physical interactions such as electrostatic interaction, van der Waals' force and hydrogen bond have been widely used to obtain MXene-based composites due to their relatively simple and convenient. While chemical interactions also are chosen for the construction of hybrid structures on account of they can introduce strong mutual coupling between MXenes and other materials, which usually manifest as the formation of chemical bonds [19, 20].

Therefore, according to the different interactions and configuration between MXenes and other substances, we summarized three common preparation methods here. The principles, procedures and relative merits of each type are also discussed.

2.1. Active surface connectionMXenes tend to connect with other objects and stack alternately to form layered structures through electrostatic force or hydrogen bond due to their electronegativity and the presence of active functional groups on their surface, these layered structures could form IMLCs through subsequent processing, such as vacuum filtration, hydrothermal or annealing.

Firstly, focusing on the electronegativity of MXenes, some positively charged ions or molecules can be adsorbed directly on the surface of them. For example, in the work recently reported by Ji et al. [21], Cu2+ are attracted to the surface of Ti3C2 flakes through directly mixing Ti3C2 flakes with copper nitrate trihydrate, the target Ti3C2/CuS with sandwich structure were obtained by hydrothermal reaction in the presence of thioacetamide (Fig. S1a in Supporting information). Furthermore, to combine more non-positively charged materials with MXenes, surfactants were chosen to modify the surface potentials of intercalators or MXenes [22-24]. In the work of Li et al. [25], MoS42- can insert into the interlayers of Ti3C2 MXene uniformly attributed to the preintercalation of CTAB which expanded the MXene's interlayer space and modified them with positively charged (Fig. 1a). In addition, ion exchange is also an important technology, Dong et al. got C/Ti3C2 composite triumphantly by in situ carbonized longchain fatty amines which intercalated into the interlayers of MXene through ion exchange with TMA+ [26].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Preparation strategies of IMLCs. (a) MoS2-in-Ti3C2 hybrids prepared by CTAB assisted intercalation. Copied with permission [25]. Copyright 2018, WILEY-VCH. (b) Abridged general view of the preparation of S@titanium oxides-Ti3C2 composite according to controlled oxidation process. (c) Raman spectra of Ti3C2 and 500-Ti3C2Ox obtained by controlling oxidation. Reproduced with permission [35]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier. (d) Schematic diagram of Ti3C2Tx MXene/CNT prepared by layer-by-layer spraying. (e) The cross section of Ti3C2Tx MXene/CNT layered structure observed by SEM. Reproduced with permission [44]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. | |

Secondly, active functional groups on the surface of MXenes also provide more possibilities for grafting other substances [27, 28]. For example, Huang et al. [29] take advantage of the functional groups (—O, —OH and —F) on the surface of MXenes and the carboxyl group (—COOH) on metal-porphyrin frameworks (MPFs) to form hydrogen bond, MXene/MPFs composites was obtained through subsequent vacuum filtering (Fig. S1b in Supporting information). Analogously, connected on the surface of Ti3C2Tx according hydrogen bond between N—H and —O/—F, pyrrole monomers in the interlayer of MXene could in situ polymerize and form pyrrole/Ti3C2Tx film [30].

Certainly, active surface connection is the most widely used method in the preparation of IMLCs, easy operating makes it more promising. But it is necessary to conduct in-depth research to achieve better use of this method and make it more controllable and universal.

2.2. Controlled oxidation processAs early in 2014, Barsoum et al. obtained a material of ordered graphite carbon flakes with TiO2 on the surface by heating MXene in air [31]. Since then, experiments and in-situ characterization techniques have been used to further study the process of oxidation [32-34]. With the development of scientific research, this method has gradually appeared in the field of preparing IMLCs for its simple and fast.

TiO2-Ti3C2 composite obtained by Huang's group through fast heating Ti3C2 MXene in air, which integrated the conductivity of Ti3C2 and the absorption ability of TiO2 to polysulfide, is an ideal sulfur host for lithium sulfur batteries (Li-S batteries) (Figs. 1b and c) [35]. In the same way, IMLCs were also obtained by choosing different oxidizing substances (such as H2O2 and CO2) and heating methods (hydrothermal, annealing, microwave) [36-39]. In consequence, the key to the success of controlled oxidation process is to understand the mechanism and the control of temperature and heating speed in the process of reaction.

2.3. Layer by layer assemblyLayer-by-layer assembly technology plays an important role in the preparation of multilayer composites since its emergence 30 years ago with the advantages of simple preparation, controllable thickness and wide application [40]. For IMLCs, Gogotsi et al. successfully obtained MXene-CNT layered composite with sandwich structure by vacuum filtrating of MXene and CNT layers alternately [41]. With the continuous progress of equipment technology, spray and atomic layer deposition (ALD) are gradually used for the more accurate control of concentration and amount [42, 43]. The MXene/CNT composite membrane obtained by spray coating is more uniform and controllable compared with vacuum filtration (Figs. 1d and e) [44]. As proved in the reported of Alshareef et al., SnO2/MXene obtained by ALD has higher cycling stability than hydrothermal and sputtering when used as lithium ion battery anodes (Fig. S1c in Supporting information) [45].

3. ApplicationIn view of the excellent properties, IMLCs have experienced rapid progress in practical application recent years. Therefore, in this section we summarized their pivotal role in various fields, expecting to provide some references for the further development of them.

3.1. Energy storage 3.1.1. SupercapacitorsSupercapacitors have been widely studied in recent years in high-power electronic devices due to their remarkable advantages of fast charge and discharge rates and long cycle life. There are two energy storage mechanisms of supercapacitors: forming electric double layer at the interface of electrode and electrolyte or occurring redox reaction on the surface or near surface of the electrode. Based on this, large specific surface area, rapid electron transport and ion diffusion, excellent redox reactivity of the electrode materials are the crux to improve the electrochemical performance of supercapacitors [46, 47].

MXenes are ideal electrode materials for supercapacitors due to their transition metal redox activity and high electrical conductivity [48]. In order to overcome the obstacles caused by stack, intercalating other substances to the interlayers of MXenes is a general approach.

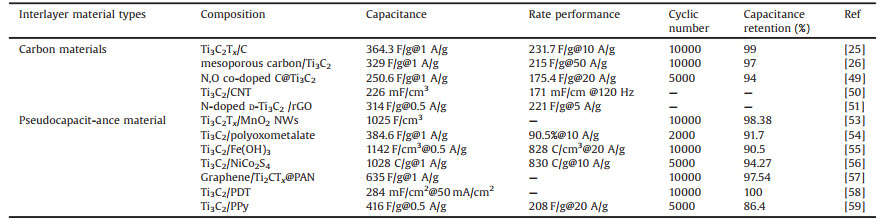

In the first place, carbon materials are commonly used as the intercalators to preparing IMLCs for supercapacitor electrodes. For instance, the electronegative Ti3C2 MXene and the modified electropositive graphene could self-assemble into a high conductive (2261 S/cm) film [6], which can prevent both MXene and rGO from stacking and accelerate the transport of electrolyte ion (Figs. 2a–c). When as a self-supporting electrode, it can achieve a volumetric capacitance of 1040 F/cm3 at a scan rate of 2 mV/s and retain 61% at 1 V/s (Fig. 2d). In addition, when assembled into a symmetrical supercapacitor, the volume energy density could reach 32.6 Wh/L (Fig. 2e). There were some other successful applications of IMLCs as supercapacitors electrodes with carbon materials as intercalator (Table 1) [25, 26, 49-51].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Application of IMLCs in energy storage. (a, b) The cross section of pure MXene and MXene/rGO layered hybrid films observed by SEM. (c) TEM images of MXene/rGO. (d) CV curves of MXene/rGO at different scan rates. (e) Gravimetric energy and power densities for symmetric supercapacitors based on pure MXene and MXene/rGO electrodes. Reproduced with permission [6]. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH. (f) Schematic diagram of preparing SnO2 nanowires@MXene and TiO2 nanorods@MXene. (g, h) cycle performance of SnO2 nanowires@MXene and TiO2 nanorods@MXene. Reproduced with permission [62]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. | |

|

|

Table 1 Performance of supercapacitors with IMLCs as electrode materials. |

Although the combination of MXenes and carbon materials can expand the capacitance to a certain extent, the general redox activity limits their energy density. Using pseudocapacitance materials instead of carbon materials as intercalator to provide additional specific capacitance is becoming an excellent choice. Rosen et al. used high conductive Mo1.33C MXene and poly(3, 4- ethylenedioxythiophene) modified by poly(styrenesulfonic acid) to form a homogeneous suspension and subsequently obtained a flexible film through vacuum filtration, achieved a ultrahigh energy density of 33.2 mWh/cm3 and a power density of 19, 470 mW/cm3 [52]. Other IMLCs constructed by MXenes and pseudocapacitance materials for supercapacitors [53-59] are also detailed in Table 1.

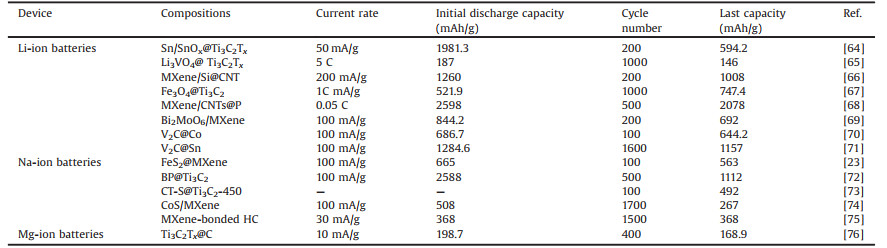

3.1.2. Alkali metal ion batteriesAlkali metal ion batteries, expanding from lithium-ion batteries to sodium, potassium and other ion batteries recent years, store energy by ion's moving through the electrolyte and interacting with the electrodes. With people's pursuit of thinner and higher endurance of portable electronic products, traditional graphite anode is unable to meet the requirements due to its relatively low theoretical capacitance, low density and poor rate performance, new anode materials with higher volumetric capacitance are urgent to be discovered [60].

According to the energy storage mechanism, taking lithium-ion batteries as representative, the ways to improve the performance of electrode materials are as follows: ⅰ) Select other materials with higher theoretical capacitance such as transition metal oxide, transition metal sulfide or polymer to provide higher specific capacitance; ⅱ) Use Si, Sn or other materials that can form reversible alloy with lithium ions as anode materials [3]. However, to realize ideal rate performance and cycling stability, the poor conductivity and easy volume expansion of the above materials must be overcome.

As new electrode materials of lithium-ion batteries [61], MXenes can also prevent the expansion and crushing of active materials during lithiation/delithiation through spatial confined effect. Meanwhile, they are also ideal bases to promote the rapid electronic transmission for super high conductivity. In the report of Xu et al., transition metal oxides with low surface energy can coated on the surface of individual Ti3C2 MXene through van der waals' force (Fig. 2f). Specifically, by forming a reversible alloy between SnO2 (theoretical capacitance 790 mAh/g) and Li+, SnO2 nanowires@MXene as electrode material can achieve a higher capacity of 530 mAh/g after 500 cycles and an initial reversible capacity of 303 mAh/g at 50 mA/g. Moveover, storage energy through intercalation/deintercalation of Li+, TiO2 nanorods@MXene achieves an initial reversible capacity of 303 mAh/g at 50 mA/g (Figs. 2g and h) [62]. Moreover, to make the electrodes thinner and more powerful, using MXene instead of soft carbon as matrix shows greater advantages. Based on this, thinner film η-MoC/MXene/C with higher conductivity shows higher performance of lithium storage and cyclic stability compared with carbonaceous materials as conductive agents [63].

It is also applicative for many other anode materials possessing high capacity but relatively low conductance, such as Si, Ge, Fe3O4, Co3O4, MnO2 and red P [64-71]. Additionally, studies on the replacement of lithium ions with sodium, potassium or magnesium ions which is larger have been gradually increased due to the limited lithium storage on the earth, fortunately, IMLCs can also be applied to these ion batteries according the adjustable layer spacing of MXenes [23, 72-76]. The details are listed in Table 2.

|

|

Table 2 Performance of alkali metal ion batteries with IMLCs as electrode materials. |

3.1.3. Li-S batteries

The general theoretical energy density of lithium-ion batteries (420 Wh/kg or 1400 Wh/L) limits their application in mobile transportation. Unlike the intercalation energy storage mechanism of lithium-ion batteries, Li-S batteries store energy by the plating and stripping of metal on the lithium anode and occurring conversion reaction on the sulfur cathode. Benefiting from their higher theoretical energy density (2500 Wh/kg or 2800 Wh/L), Li-S batteries become a promising substitute for lithium-ion battery since their inception in 1960 [77, 78]. Despite their great advantages, the development of Li-S batteries encounters some obstacles: First, low utilization of active materials resulted from the insulation of sulfur cathode and its intermediates lithium polysulfides (LiPSs); Second, shuttle effect of LiPSs in electrolyte may cause the loss of active materials, the contamination of lithium anode and the damage of membrane; Third, low rate performance and short cycle life due to the volume expansion from sulfur to LiPSs [3, 79].

MXenes have become promising materials for mitigating these problems mentioned above. Sulfur was inserted and fixed in the interlayer of MXenes, which not only increase the load of active substances, improve the conductivity of electrodes, but also prevent the structure damage caused by the volume change of active substances during charging and discharging [80]. Yang and Zhang have achieved a Ti3C2Tx/S flexible paper through vacuum filtration and sulfur impregnation. Due to the high electrical conductivity, mechanical property and the strong adsorption capacity for LiPS of MXene nanosheets, the Ti3C2Tx/S paper get an initial capacity of 1169 mAh/g and just 0.014% capacity decay after 1500 cycles (Figs. S2a-c in Supporting information) [81]. Besides, for the separator, Lai et al. had designed T@CP through the one step self-assembled of Ti3C2 MXene and polyethyleneimine functionalized CNT, in which the intercalation of CNT between MXene sheets provides spacious channels for the transport of Li ions, alleviates the shuttle of LiPSs and the growth of lithium dendrite (Fig. S2d in Supporting information) [82].

To make the best use of the stronger adsorption energy of TiO2 to LiPSs, TiO2 quantum dots/Ti3C2Tx becomes a potential material for sulfur host with higher sulfur loading and weaker shuttle effect of LiPSs [83, 84]. Moreover, CNT, carbon fibers and GO are also intercalators for MXenes to enhance ion and electron transport while mitigated LiPSs shuttling through physical shielding and strong chemical affinity [85-88].

3.2. CatalysisPrecious metals play important roles in catalysis, but the features of scarcer and expensive hinder them from widespread industrial application. The studies of substitution for precious metals have been carried out for many years, however, catalysts which can replace precious metals generally have inherent low conductivity, limited activity surface area and strong tendency of aggregation.

2D MXenes' excellent electrical conductivity, adjustable electronic structure and chemical stability make them ideal conjugate and carrier for the active substances including metals, metal oxides, chalcogenides, metal organic frames and graphene derivatives via as electron transport mediums, but also ensure the accessible surface sites of the active substances, prevent them from leaching via fixing them in the interlayer [89].

In 2015, Qiao et al. constructed a self-supporting flexible film with small impedance and low current loss during cycling by vacuum filtration of g-C3N4 and Ti3C2 sheets. It also demonstrated excellent oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity when used as oxygen electrodes for Zn-air batteries (Figs. 3a–c) [90]. Similarly, IMLCs are also widely used to further improve the performance of electrochemical hydrogen evolution. CoxMo2-xC/MXene/N-doped carbon obtained by simple coannealing of MXene, Mo7O246-, Co2+ and dopamine demonstrated higher activity of hydrogen evolution reaction in the full pH range and seawater than commercial Pt/C [91]. NiFe-LDH/MXene/Nickle foam electrode in which the nickel foam coated with MXene as superconducting skeleton contributed to large current density, greatly promoted the high adsorption and activation of NiFe-LDH on the surface to water molecules [92].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Application of IMLCs in catalysis and sensors. (a) Preparation process of porous g-C3N4/Ti3C2 film. (b) SEM image and photo of g-C3N4/Ti3C2 film. (c) The polarization curves of g-C3N4/Ti3C2 film and IrO2/C powder in the whole OER/ORR region in the three-electrode system. Reproduced with permission [90]. Copyright 2016, Wiley-VCH. (d) Schematic diagram of preparing Ti3C2/NMPs film. (e) Schematic diagram of flexible sensor made by Ti3C2/NMPs thin film. Reproduced with permission [105]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. | |

In addition to energy conversion, IMLCs also play significant roles in catalyzing the degradation of pollutants. The Co3O4/MXene with sandwich shape obtained by immersion evaporation could effectively catalyze the degradation of peroxymonosulfate to bisphenol at a rate of 95% in seven minutes [93]. α-Fe2O3/Ti3C2 MXene composite has high photocatalytic activity for rhodamine B degradation under visible light irradiation [94].

3.3. SensorsOn account of the high conductivity and biocompatibility of MXenes, IMLCs have also been widely used in the sensors which reflect mainly in three aspects: biomolecule sensors, environmental pollutant sensors and mechanical sensors.

Due to their unique hypotoxicity and biocompatibility, MXenes can be used as excellent substrates of biosensitive material with low electrical conductivity such as enzymes, proteins and nucleic acids for the detection of specific biological substances [95-97]. For instance, TiO2-Ti3C2 obtained by hydrothermal was successfully used as the substrate of hemoglobin to detecting H2O2, in which TiO2 served as the protective layer of hemoglobin and MXene greatly improved the electron transfer rate in hemoglobin [98].

Except for biomolecule sensors, IMLCs also perform well in the detection of environmental pollutants and environmental elements. In the work of Yang et al., [Ti-O]-H+ and [Ti-O]-K+ formed by the interaction between KOH and Ti3C2 flakes can improve the adsorption ability for heavy metal ions and reduce them to metal with high electronic transmission capability. As a result, the detection limit of Cd(Ⅱ), Pb(Ⅱ), Cu(Ⅱ) and Hg(Ⅱ) were 0.098, 0.041, 0.032 and 0.130 μmol/L, respectively [99]. Moreover, there were many other studies on the application of IMLCs to the detection of humidity sensors [100], MXene immobilized enzyme used to detect phenol [101], nafion/Ti3C2Tx MXene for the detection of bromate [102], acetylcholinesterase/chitosan-Ti3C2Tx for organophosphate pesticides [103].

Moreover, benefiting from the high conductivity after mechanical deformation, MXenes show great potential in mechanical sensors and can be used to capture physiological signals and detect subtle activities of human [43, 104]. More recently, Shen et al. exploited a series of alternating sequences of MXene and natural microcapsules (NMPs) to design a flexible pressure sensor. Specifically, hollow NMPs were confined between the MXene layers and forms an interlocking structure through their own spine, the sensors prepared by this biocomposite film can stably detect static pressure signals on account of the excellent flexibility and mechanical deformability (Figs. 3d and e) [105].

3.4. Electromagnetic interference (EMI) shieldingThe emergence of electronic products have provided great convenience for human and promoted the development of aerospace engineering and medical treatment greatly. But at the same time EMI also threatens human health and affects the function and lifetime of electronic devices. Developing high performance EMI shielding materials is the most effective and imperative way to alleviate this problem [106].

Thanks to their excellent conductivity and typical twodimensional lamellar structure, MXenes have strong ability to absorb and reflect electromagnetic waves compared with metal and carbon-based fillers. Meanwhile, MXenes have significant advantages in building lightweight and flexible materials [107, 108]. However, easy stacking results in a sharp reduction of available surface area in practical application. Fortunately, in order to give full use of the EMI shielding performance of MXenes, Gogotsi et al. make sodium alginate and MXene to form a selfsupporting membrane with layered structure through the reaction occured in the interlayer of MXene, the EMI shielding performance can reach 92 decibels with only 45 μm thick (Figs. 4a and b) [109], which offer a new solution of constructing MXene-based composite membranes for EMI [110-112].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Application of IMLCs in EMI shielding and biomedicine. (a) EMI shielding mechanism of MXene. (b) Preparation process of sodium alginate/MXene self-supporting membrane. Reproduced with permission [109]. Copyright 2016, Science Publishing Group. (c) Schematic diagram the fabrication of Ti3C2@mMSNs-RGD. (d) Schematic diagram of collaborative treatment of HCC cells [123]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. | |

Apart from constructing composite membranes, the construction of 3D MXene macrostructure is also an ingenious solution [113-115]. Research conducted by Zhang et al. further confirmed the outstanding EMI shielding performances of Ti3C2Tx/rGO hybrid aerogels [116]. The 3D porous and highly conductive aerogels endows epoxy nanocomposite with excellent EMI shielding performances of more than 50 dB in the X-band at a low MXene content of 0.74 vol% (Figs. S3a-c in Supporting information).

3.5. BiomedicineIn addition to the outstanding applications summarized above, IMLCs also show fascinating potential in antibacterial, biological imaging, diagnosis and treatment. Taken advantage of the fluorescence quenching effect of MXene to rhodamine B (RhB), Nie et al. [117] obtained a novel fluorescent probe for imaging of phospholipase D. When natural phospholipids doped with RhB were modified on the surface of Ti3C2, the fluorescence quenching rate of RhB are 95%, however, in the presence of phosolipase D, RhB breaks away from MXene and fluorescence recovers (Fig. S4a in Supporting information). The lowest detection concentration can reach 0.01 U/L (Figs. S4b and c in Supporting information). Furthermore, thanks to the biocompatibility, strong absorption to the near-infrared region and high photothermal conversion efficiency of MXenes, IMLCs also show great utilization potentiality in photothermal therapy [118, 119]. Shi et al. synthesized polyvinylpyrrolidone modified Nb2C nanosheets with higher physiological stability successfully and achieved the goal of in vivo photothermal ablation of mouse tumors efficiently [120].

In view of surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are still the three major treatments for cancer [121, 122]. Researchers have gradually turned to realize the synergy between photothermal therapy and other treatment methods by constructing MXene-based composites. Recently, Yang et al. [123] realized the photothermal therapy and chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) simultaneously. Firstly, mesoporous-silica layer which is used as the carrier of the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin is coated on the surface of Ti3C2 MXene (Ti3C2@mMSNs). Subsequently, with the help of arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD), the Ti3C2@mMSNsRGD can target HCC cells well, realize the collaborative therapy of photothermal therapy and chemotherapy (Figs. 4c and d).

Morover, Gogotsi et al. [124] have demonstrated the excellent antibacterial properties of MXene by preparing MXene coated polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. In another study, the research group of Mahmoud fabricated a film of Ag/MXene. Under the optimal experimental condition, the 21% Ag@MXene film can inhibit the growth of 99% escherichia coli [125]. These all suggest that modified MXene membranes have broad application prospects in the field of water and wastewater treatment.

The surface and interface structure will affect materials' performance in many ways. There are numerous studies on the application of IMLCs, but most of them stay in the study on performance, fewer studies focus on the mechanisms of interactions between MXenes surface and other materials. Enhanced understanding of the interactions between MXenes surface and other materials is conducive to the synthesis of more MXenesbased hybrid structures.

4. Conclusions and outlookThe unique composition and physicochemical properties of 2D MXenes have attracted extensive attention. Combining MXenes with other substances to form IMLCs is one of the common research directions of MXenes to obtain unique application advantages. This paper mainly summarized the preparation and application of IMLCs, especially expounds the unique advantages and research progress of the structure and characteristics of IMLCs in various applications.

The continuous emergence of new requirements will definitely promote the development of IMLCs to more extensive and in-depth applications, especially in flexible and bionic devices. Although some achievements have been made so far, there are still some areas to improve: ⅰ) controllable adjustment of the component units, interfacial interactions and assembly mode, structure and morphology of the IMLCs at nanoscale as required during preparation; ⅱ) further understanding of the synergistic mechanism of IMLCs and design multi-components composite structure so as to realize more complex and efficient applications.

Therefore, further studies on the surface properties of MXenes are needed to control and facilitate interfacial interactions in the preparation of composites. Moreover, rapid and simple characterization technology for structure and performance are needed to realize precise regulation of reaction conditions, further understanding of the synergistic mechanism. Finally, given the advantages of IMLCs in the preparation of flexible materials, the use of biomimetic technology to prepare IMLCs with fine hierarchical structure is bound to play an increasingly important role in the field of new flexible and wearable materials.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21776061, 21978069, 21707081 and 41807128) and the program for Science & Technology Innovation Team in Universities of Henan Province (No. 19IRTSTHN029).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary material related to this article canbefound, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2020.02.046.

| [1] |

S.Z. Butler, S.M. Hollen, L.Y. Cao, et al., ACS Nano 7 (2013) 2898-2926. DOI:10.1021/nn400280c |

| [2] |

M. Naguib, M. Kurtoglu, V. Presser, et al., Adv. Mater. 23 (2011) 4248-4253. DOI:10.1002/adma.201102306 |

| [3] |

J. Pang, R.G. Mendes, A. Bachmatiuk, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 48 (2019) 72-133. DOI:10.1039/C8CS00324F |

| [4] |

M. Khazaei, A. Ranjbar, M. Arai, T. Sasaki, S. Yunoki, J. Mater. Chem. C 5 (2017) 2488-2503. |

| [5] |

M. Xu, T. Liang, M. Shi, H. Chen, Chem. Rev. 113 (2013) 3766-3798. DOI:10.1021/cr300263a |

| [6] |

J. Yan, C.E. Ren, K. Maleski, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 27 (2017) 1701264. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201701264 |

| [7] |

Y. Xue, Q. Zhang, W. Wang, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 7 (2017) 1602684. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201602684 |

| [8] |

M.Q. Zhao, X. Xie, C.E. Ren, et al., Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1702410. DOI:10.1002/adma.201702410 |

| [9] |

Q. Zhao, Q. Zhu, J. Miao, et al., Small 15 (2019) 1904293. DOI:10.1002/smll.201904293 |

| [10] |

Y. Dong, S. Zheng, J. Qin, et al., ACS Nano 12 (2018) 2381-2388. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.7b07672 |

| [11] |

Y. Xia, T.S. Mathis, M.Q. Zhao, et al., Nature 557 (2018) 409-412. DOI:10.1038/s41586-018-0109-z |

| [12] |

O. Mashtalir, M. Naguib, V.N. Mochalin, et al., Nat. Commun. 4 (2013) 1716. DOI:10.1038/ncomms2664 |

| [13] |

M. Ghidiu, M.R. Lukatskaya, M.Q. Zhao, et al., Nature 516 (2014) 78-81. DOI:10.1038/nature13970 |

| [14] |

J. Halim, M.R. Lukatskaya, K.M. Cook, et al., Chem. Mater. 26 (2014) 2374-2381. DOI:10.1021/cm500641a |

| [15] |

M.R. Lukatskaya, O. Mashtalir, C.E. Ren, et al., Science 341 (2013) 1502-1505. DOI:10.1126/science.1241488 |

| [16] |

O. Mashtalir, M.R. Lukatskaya, M.Q. Zhao, et al., Adv. Mater. 27 (2015) 3501-3506. DOI:10.1002/adma.201500604 |

| [17] |

Y. Lei, W. Zhao, Y. Zhang, et al., Small 15 (2019) 1901190. DOI:10.1002/smll.201901190 |

| [18] |

S. Xu, Y. Dall'Agnese, J. Li, et al., Chemistry 24 (2018) 18556-18563. DOI:10.1002/chem.201805162 |

| [19] |

R. Li, W. Sun, C. Zhan, P.R.C. Kent, D. Jiang, Phys. Rev. B 99 (2019) 2469-9950. |

| [20] |

X. Wu, Z. Wang, M. Yu, L. Xiu, J. Qiu, Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1607017. DOI:10.1002/adma.201607017 |

| [21] |

Z. Pan, F. Cao, X. Hu, X. Ji, J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 8984-8992. DOI:10.1039/C9TA00085B |

| [22] |

J.M. Luo, J. Zheng, J. Nai, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 29 (2019) 1808107. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201808107 |

| [23] |

J. Luo, W. Zhang, H. Yuan, et al., ACS Nano 11 (2017) 2459-2469. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.6b07668 |

| [24] |

J. Luo, C. Wang, H. Wang, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 29 (2019) 1805946. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201805946 |

| [25] |

K. Ma, H. Jiang, Y. Hu, C. Li, Adv. Funct. Mater. 28 (2018) 1804306. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201804306 |

| [26] |

L. Shen, X. Zhou, X. Zhang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 6 (2018) 23513-23520. DOI:10.1039/C8TA09600G |

| [27] |

A.E. Allah, J. Wang, Y.V. Kaneti, et al., Nano Energy 65 (2019) 103991. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.103991 |

| [28] |

Y. Wang, X. Wang, X. Li, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 29 (2019) 1900326. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201900326 |

| [29] |

W. Zhao, J. Peng, W. Wang, et al., Small 15 (2019) 1901351. DOI:10.1002/smll.201901351 |

| [30] |

M. Boota, B. Anasori, C. Voigt, et al., Adv. Mater. 28 (2016) 1517-1522. DOI:10.1002/adma.201504705 |

| [31] |

M. Naguib, O. Mashtalir, M.R. Lukatskaya, et al., Chem. Commun. (Camb) 50 (2014) 7420-7423. DOI:10.1039/C4CC01646G |

| [32] |

H. Ghassemi, W. Harlow, O. Mashtalir, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 2 (2014) 14339-14343. DOI:10.1039/C4TA02583K |

| [33] |

D.A.H. Hanaor, C.C. Sorrell, J. Mater. Sci. 46 (2010) 855-874. |

| [34] |

R.B. Rakhi, Bilal Ahmed, M.N. Hedhili, H. Anjum Dalaver, H.N. Alshareef, Chem. Mater. 27 (2015) 5314-5323. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b01623 |

| [35] |

H. Pan, X. Huang, R. Zhang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 358 (2019) 1253-1261. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2018.10.026 |

| [36] |

B. Ahmed, D.H. Anjum, M.N. Hedhili, Y. Gogotsi, H.N. Alshareef, Nanoscale 8 (2016) 7580-7587. DOI:10.1039/C6NR00002A |

| [37] |

M. Han, X. Yin, H. Wu, Z. Hou, C. Song, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8 (2016) 21011-21019. DOI:10.1021/acsami.6b06455 |

| [38] |

C.J. Zhang, S.J. Kim, M. Ghidiu, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 26 (2016) 4143-4151. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201600682 |

| [39] |

X. Zhang, Y. Liu, S. Dong, Z. Ye, Y. Guo, Ceram. Int. 43 (2017) 11065-11070. DOI:10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.05.151 |

| [40] |

S. Zhao, F. Caruso, L. Dahne, et al., ACS Nano 13 (2019) 6151-6169. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.9b03326 |

| [41] |

M.Q. Zhao, C.E. Ren, Z. Ling, et al., Adv. Mater. 27 (2015) 339-345. DOI:10.1002/adma.201404140 |

| [42] |

W. Tian, A.Vahid Mohammadi, Z. Wang, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 2558. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-10631-0 |

| [43] |

M.Q. Zhao, N. Trainor, C.E. Ren, et al., Adv. Mater. Technol. 4 (2019) 1800639. DOI:10.1002/admt.201800639 |

| [44] |

Y. Cai, J. Shen, G. Ge, et al., ACS Nano 12 (2018) 56-62. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.7b06251 |

| [45] |

B. Ahmed, D.H. Anjum, Y. Gogotsi, H.N. Alshareef, Nano Energy 34 (2017) 249-256. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.02.043 |

| [46] |

L. Li, Y. Zhou, H. Zhou, et al., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 7 (2018) 1337-1346. |

| [47] |

H. Zhou, Y. Zhou, L. Li, et al., ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 7 (2019) 9281-9290. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b00279 |

| [48] |

M. Hu, C. Cui, C. Shi, et al., ACS Nano 13 (2019) 6899-6905. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.9b01762 |

| [49] |

Z. Pan, X. Ji, J. Power Sources 439 (2019) 227068. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.227068 |

| [50] |

S. Xu, W. Liu, B. Hu, X. Wang, Nano Energy 58 (2019) 803-810. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.01.079 |

| [51] |

L. Yang, W. Zheng, P. Zhang, et al., Electrochim. Acta 300 (2019) 349-356. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2019.01.122 |

| [52] |

L. Qin, Q. Tao, A. El Ghazaly, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 28 (2018) 1703808. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201703808 |

| [53] |

J. Zhou, J. Yu, L. Shi, et al., Small 14 (2018) 1803786. DOI:10.1002/smll.201803786 |

| [54] |

S. Chen, Y. Xiang, M.K. Banks, et al., Nanoscale 10 (2018) 20043-20052. DOI:10.1039/C8NR05760E |

| [55] |

Z. Fan, Y. Wang, Z. Xie, et al., Nanoscale 10 (2018) 9642-9652. DOI:10.1039/C8NR01550C |

| [56] |

J. Fu, L. Li, J.M. Yun, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 375 (2019) 121939. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.121939 |

| [57] |

J.J. Fu, J.M. Yun, S.X. Wu, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10 (2018) 34212-34221. DOI:10.1021/acsami.8b10195 |

| [58] |

X. Wu, B. Huang, R.Q. Wang, Y. Wang, Chem. Eng. J. 378 (2019) 122246. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.122246 |

| [59] |

X. Jian, M. He, L. Chen, et al., Electrochim. Acta 318 (2019) 820-827. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2019.06.045 |

| [60] |

N.K. Chaudhari, H. Jin, B. Kim, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 5 (2017) 24564-24579. DOI:10.1039/C7TA09094C |

| [61] |

R. Cheng, T. Hu, H. Zhang, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 123 (2018) 1099-1109. |

| [62] |

Y.T. Liu, P. Zhang, N. Sun, et al., Adv. Mater. 30 (2018) 1707334. DOI:10.1002/adma.201707334 |

| [63] |

S. Niu, Z. Wang, M. Yu, et al., ACS Nano 12 (2018) 3928-3937. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.8b01459 |

| [64] |

D.C. Zuo, S.C. Song, C.S. An, et al., Nano Energy 62 (2019) 401-409. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.05.062 |

| [65] |

Y. Huang, H. Yang, Y. Zhang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 11250-11256. DOI:10.1039/C9TA02037C |

| [66] |

S. Liu, X. Zhang, P. Yan, et al., ACS Nano 13 (2019) 8854-8864. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.9b02129 |

| [67] |

Y. Wang, Y. Li, Z. Qiu, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 6 (2018) 11189-11197. DOI:10.1039/C8TA00122G |

| [68] |

S. Zhang, H. Liu, B. Cao, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 21766-21773. DOI:10.1039/C9TA07357D |

| [69] |

P. Zhang, D. Wang, Q. Zhu, et al., Nano-Micro Lett. 11 (2019) 81. DOI:10.1007/s40820-019-0312-y |

| [70] |

C. Wang, H. Xie, S. Chen, et al., Adv. Mater. 30 (2018) 1802525. DOI:10.1002/adma.201802525 |

| [71] |

C. Wang, S. Chen, H. Xie, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 9 (2019) 1802977. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201802977 |

| [72] |

C.F. Du, Q. Liang, Y. Zheng, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10 (2018) 33779-33784. DOI:10.1021/acsami.8b13750 |

| [73] |

R. Zhao, Z. Qian, Z. Liu, et al., Nano Energy 65 (2019) 104037. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104037 |

| [74] |

Y. Zhang, R. Zhan, Q. Xu, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 357 (2019) 220-225. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2018.09.142 |

| [75] |

N. Sun, Q. Zhu, B. Anasori, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 29 (2019) 1906282. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201906282 |

| [76] |

F. Liu, Y. Liu, X. Zhao, X. Liu, Li. Fan, J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 16712-16719. DOI:10.1039/C9TA02212K |

| [77] |

R.J.Jo.E.C. Jasinski, J. Electroanal, Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 26 (1970) 189-194. DOI:10.1016/S0022-0728(70)80302-3 |

| [78] |

Y. Yang, G. Zheng, Y. Cui, Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2013) 3018-3032. DOI:10.1039/c2cs35256g |

| [79] |

Z.W. Seh, Y. Sun, Q. Zhang, Y. Cui, Chem. Soc. Rev. 45 (2016) 5605-5634. DOI:10.1039/C5CS00410A |

| [80] |

Z. Xiao, Z. Li, X. Meng, R. Wang, J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 22730-22743. DOI:10.1039/C9TA08600E |

| [81] |

H. Tang, W. Li, L. Pan, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 29 (2019) 1901907. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201901907 |

| [82] |

D. Guo, F. Ming, H. Su, et al., Nano Energy 61 (2019) 478-485. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.05.011 |

| [83] |

X.T. Gao, Y. Xie, X.D. Zhu, et al., Small 14 (2018) 1802443. DOI:10.1002/smll.201802443 |

| [84] |

L. Jiao, C. Zhang, C. Geng, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 9 (2019) 1900219. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201900219 |

| [85] |

Q. Jin, L. Li, H. Wang, et al., Electrochim. Acta 312 (2019) 149-156. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2019.04.182 |

| [86] |

L.P. Lv, C.F. Guo, W. Sun, Yong Wang, Small 15 (2018) 1804338. |

| [87] |

Z. Wang, N. Zhang, M. Yu, et al., J. Energy Chem. 37 (2019) 183-191. DOI:10.1016/j.jechem.2019.03.012 |

| [88] |

Q. Zhao, Q. Zhu, J. Miao, P. Zhang, B. Xu, Nanoscale 11 (2019) 8442-8448. |

| [89] |

J. Peng, X. Chen, W.J. Ong, X. Zhao, N. Li, Chem. 5 (2019) 18-50. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.08.037 |

| [90] |

T.Y. Ma, J.L. Cao, M. Jaroniec, S.Z. Qiao, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 1138-1142. DOI:10.1002/anie.201509758 |

| [91] |

X. Wu, S. Zhou, Z. Wang, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 9 (2019) 1901333. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201901333 |

| [92] |

M. Yu, Z. Wang, J. Liu, et al., Nano Energy 63 (2019) 103880. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.103880 |

| [93] |

Y. Liu, R. Luo, Y. Li, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 347 (2018) 731-740. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2018.04.155 |

| [94] |

H. Zhang, M. Li, J. Cao, et al., Ceram. Int. 44 (2018) 19958-19962. DOI:10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.07.262 |

| [95] |

H. Liu, C. Duan, C. Yang, et al., Sens. Actuator. B-Chem. 218 (2015) 60-66. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2015.04.090 |

| [96] |

R.B. Rakhi, P. Nayak, C. Xia, H.N. Alshareef, Sci. Rep. 6 (2016) 36422. DOI:10.1038/srep36422 |

| [97] |

J. Zheng, J. Diao, Y. Jin, et al., J. Electrochem. Soc. 165 (2018) B227-B231. DOI:10.1149/2.0051807jes |

| [98] |

F. Wang, C. Yang, M. Duan, Y. Tang, J. Zhu, Biosens. Bioelectron. 74 (2015) 1022-1028. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2015.08.004 |

| [99] |

X. Zhu, B. Liu, H. Hou, et al., Electrochim. Acta 248 (2017) 46-57. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2017.07.084 |

| [100] |

E.S. Muckley, M. Naguib, H.W. Wang, et al., ACS Nano 11 (2017) 11118-111126. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.7b05264 |

| [101] |

L. Wu, X. Lu, Dhanjai, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 107 (2018) 69-75. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2018.02.021 |

| [102] |

P.A. Rasheed, R.P. Pandey, K. Rasool, K.A. Mahmoud, Sens. Actuator, B-Chem. 265 (2018) 652-659. |

| [103] |

L. Zhou, X. Zhang, L. Ma, et al., BioChem. Eng. J. 128 (2017) 243-249. DOI:10.1016/j.bej.2017.10.008 |

| [104] |

X. Shi, H. Wang, X. Xie, et al., ACS Nano 13 (2019) 649-659. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.8b07805 |

| [105] |

K. Wang, Z. Lou, L. Wang, et al., ACS Nano 13 (2019) 9139-9147. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.9b03454 |

| [106] |

H. Lv, Y. Guo, Z. Yang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. C 5 (2017) 491-512. DOI:10.1039/C6TC03026B |

| [107] |

M.S. Cao, Y.Z. Cai, P. He, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 359 (2019) 1265-1302. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2018.11.051 |

| [108] |

S. Hu, S. Li, W. Xu, et al., Ceram. Int. 45 (2019) 19902-19909. DOI:10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.06.246 |

| [109] |

F. Shahzad, M. Alhabeb, C.B. Hatter, et al., Science 353 (2016) 1137-1140. DOI:10.1126/science.aag2421 |

| [110] |

W.T. Cao, F.F. Chen, Y.J. Zhu, et al., ACS Nano 12 (2018) 4583-4593. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.8b00997 |

| [111] |

X. Jin, J. Wang, L. Dai, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 380 (2020) 122475. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.122475 |

| [112] |

G.-M. Weng, J. Li, M. Alhabeb, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 28 (2018) 1803360. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201803360 |

| [113] |

Z. Chen, C. Xu, C. Ma, W. Ren, H.M. Cheng, Adv. Mater. 25 (2013) 1296-1300. DOI:10.1002/adma.201204196 |

| [114] |

Z. Fan, D. Wang, Y. Yuan, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 381 (2020) 122696. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.122696 |

| [115] |

J. Liu, H.B. Zhang, R. Sun, et al., Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1702367. DOI:10.1002/adma.201702367 |

| [116] |

S. Zhao, H.B. Zhang, J.Q. Luo, et al., ACS Nano 12 (2018) 11193-11202. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.8b05739 |

| [117] |

X. Zhu, L. Fan, S. Wang, et al., Anal. Chem. 90 (2018) 6742-6748. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00581 |

| [118] |

C. Dai, Y. Chen, X. Jing, et al., ACS Nano 11 (2017) 12696-12712. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.7b07241 |

| [119] |

G. Liu, J. Zou, Q. Tang, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9 (2017) 40077-40086. DOI:10.1021/acsami.7b13421 |

| [120] |

H. Lin, S. Gao, C. Dai, Y. Chen, J. Shi, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 16235-16247. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b07818 |

| [121] |

K. Liu, D. Zheng, J. Zhao, et al., J. Mater. Chem. B 6 (2018) 4738-4746. DOI:10.1039/C8TB01295D |

| [122] |

Y. Liu, D. Zheng, Y. Ma, et al., ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4 (2018) 1641-1650. |

| [123] |

Z. Li, H. Zhang, J. Han, et al., Adv. Mater. 30 (2018) 1706981. DOI:10.1002/adma.201706981 |

| [124] |

K. Rasool, K.A. Mahmoud, D.J. Johnson, et al., Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 1598. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-01714-3 |

| [125] |

R.P. Pandey, K. Rasool, V.E. Madhavan, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 6 (2018) 3522-3533. DOI:10.1039/C7TA10888E |

2020, Vol. 31

2020, Vol. 31