b University of Chinese Academy Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Organic optoelectronic materials have drawn widespread attention from both academia and industry in the past decades. Charge transport is an essential process and important for the optoelectronic mechanisms and performance of the devices [1]. Electronic couplings between adjacent molecules and site energies are two key factors to tune the charge transport process [2, 3]. The site energies are not only determined by intrinsic characteristics of isolated molecules, but also closely related to the electronic polarization of the surrounding environment in the solid state [4, 5]. To date, the researches on electronic polarization mainly concentrate on classical nonpolar molecular systems, such as naphthalene, anthracene, tetracene, pentacene, and fullerene [4-9].

Recently, dipolar π-conjugated molecules have achieved remarkable advances in organic optoelectronic properties. Based on the donor-acceptor (D-A) structures, organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials have been designed and achieved high external quantum efficiencies [10, 11]. D-A π-conjugated molecules and polymers have been also applied in organic solar cells (OSCs) [12-18]. For example, the power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) of the devices based on the dipolar small molecule donor of DTDCTB exceeded 8% for a single junction [14, 15], and the devices based on the dipolar DTDCPB even achieved 15% for a tandem junction [19]. It should be noted that recently, the highest PCEs of single-junction and tandem OSCs have been over 16% [20] and 17.3% [21], respectively. At the same time, the charge transport performance of dipolar organic semiconductors have been greatly improved [22, 23]. The thin film transistors exhibited hole mobilities of 0.18 cm2 V-1 s-1 and on/off ratio of 106 for the dipolar molecules based on merocyanine [24], and the hole mobilities could be as high as 0.45 cm2 V-1 s-1 for the dipolar squaraine dyes [25].

However, the electronic polarization effect has been rarely studied for the dipolar molecular systems. Intuitively, compared with nonpolar molecular systems, there are strong electrostatic interaction and inductive effect in dipolar ones. Can the larger dipole moments really bring stronger electronic polarization effect in organic dipolar molecular systems? In addition, organic semiconductors can have various molecular packing modes, such as herringbone, brickwork, and lamellar packing motifs [26, 27]; these different molecular aggregation structures can lead to different degrees of electronic polarization [6, 28]. Owing to preferential dipole-dipole interaction, the dipolar molecules often tend to form one-dimensional anti-parallel π-π stacking. Will the π-π stacks make the outstanding contribution to the total polarization energy in the dipolar systems? With those natural questions, we choose a typical small dipolar molecule, 1, 2, 3, 4- tetrafluoro-6, 7-dimethylnaphthalene (TFDMN) [29] as a case study. As shown in Fig. S1 (Supporting information), this molecule has the same π-conjugated core as the nonpolar naphthalene but with electron-donating substituents of methyl groups and electron-withdrawing substituents of fluorine atoms at two ends, and the crystal structure exhibits one-dimensional antiparallel stacking.

According to the Lyons relation [30], the polarization energy for a positive or negative charge carrier can be calculated by the following equations [6, 28]:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

Here IP and EA represent the ionization potential and electron affinity, respectively; they are calculated as the energy difference between the ionic state and the neutral state.

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

where Ecation, Eanion, and Eneutral denote the total potential energies of the system with the central molecule in the cationic, anionic, and neutral states, respectively.

In our study, the total potential energies were calculated by the polarizable force field method based on AMOEBA (Atomic Multipole Optimized Energetics for Biomolecular Applications) [31-33]. For AMOEBA, the multipole moment parameters are derived directly from quantum mechanical density matrix and able to reproduce the electrostatic interaction. It was reported that AMOEBA force field can give good description of electronic polarization for oligoacene systems [34]. On the other hand, as a molecular mechanics method, the computational cost is relatively low for AMOEBA. To parameterize the force field of AMOEBA, atom-centered multipoles were obtained with Stone's GDMA program via distributed multipole fitting of the single-particle density matrix [35]. The original integration algorithm named Gauss-Hermite quadrature was used for an exact and efficient analysis. The electronic density matrices of neutral, cationic and anionic states were computed by density functional theory at the B3LYP/6–311 G(d, p) level [36, 37], as implemented in the Gaussian09 program [38]. The atomic polarizabilities were chosen according to the Thole model [39, 40], while the aromatic H and C atomic isotropic polarizabilities were set to 0.696 and 1.750 Å3, as proposed by Yin et al. [36].

The crystal molecular packing structure of TFDMN is obtained from the Cambridge structural database without further geometry optimization. To illustrate the structure-property relation, a series of spherical clusters, planar disks, and one-dimensional (1D) stack are generated for the calculations of polarization energies (Fig. 1). The radius of the three-dimensional (3D) clusters is changed from 10 to 50 Å to extrapolate the bulk polarization energies. The 1D stack is extracted along the π-π stacking direction. Through extending the 1D stack along different adjacent directions (Fig. S2 in Supporting information), three kinds of 2D disks are constructed and the radius of the 2D disks is changed from 10 Å to 80 Å. All the total potential energy calculations utilizing the AMOEBA polarizable force field have been carried out with the Tinker software package [41].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (a) 3D cluster model of TFDMN and the charged molecule is set at the center. (b) 1D stack model of TFDMN with the charged molecule at the middle position. (c) Illustration of three-stack models with the TFDMN molecule represented by an arrow. (d, e, f) Top and side views of three kinds of 2D disk models: 2D-Ⅰ (d), 2D-Ⅱ (e) and 2D-Ⅲ (f). | |

Dipolar molecules have strong intermolecular interaction due to large molecular polarities. To characterize the molecular polarities, electrostatic potential (ESP) maps of TFDMN molecules were calculated and shown in Fig. 2. The dipole moments of the neutral, cationic, and anionic states exhibit the same direction and are in accordance with the molecular C2v axis. The dipole moment of the neutral TFDMN molecule is 4.56 Debye. Upon negatively charged, the molecular dipole moment is decreased to 2.17 Debye. In contrast, the cationic state has a stronger dipole moment of 5.85 Debye. The different dipole moments may result in difference between the polarization energies for the positive and negative charge carriers.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Electrostatic potential maps and dipole moments of the TFDMN molecule in the neutral (a), anionic (b) and cationic (c) states and electrostatic potential maps of the antiparallel stacking TFDMN dimer (d). Upper panel: top view, lower panel: side view. | |

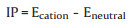

Fig. 3a shows the plot of the polarization energies vs the inverse of the cubic root of the number of molecules (N-1/3) for the different sizes of clusters. The polarization energies of the bulk materials can be obtained by extrapolation to infinite radius of the cluster (N-1/3 = 0) [42-44]. It can be found that there is a good linear correlation between the polarization energy and N-1/3. As seen from Fig. S3 (Supporting information), the electronic polarization energies are almost converged from the radius of 30 Å. The extrapolated results point to that the values of P+ and P- are -1.088 and -0.922 eV for the bulk material, respectively. This means that the positive charge (hole) is more stabilized by the surrounding environment with respect to the negative charge (electron), which is consistent with the stronger dipole moment in the cationic state. Unexpectedly, the polarization energies obtained for TFDMN are similar to or even smaller than those of the nonpolar counterpart of naphthalene reported by Yin et al. (-1.57 and -1.13 eV for hole and electron, respectively) and by Ryno et al. (-1.14 and -1.03 eV for hole and electron, respectively) [36, 42].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) Polarization energies of the charge carriers in the clusters versus the inverse of the cubic root of the number of molecules. (b) Polarization energies of the charge carriers in the π-π stack versus the inverse of the number of molecules. (c) Polarization energies of the positive charge carrier in the three-stack models as a function of the inter-stack distance. (d, e, f) Polarization energies of the charge carriers in the 2D-Ⅰ, 2D-Ⅱ, and 2D-Ⅲ disks versus the inverse of the square root of the number of molecules. | |

To reveal the electronic polarization effect along the onedimensional π-π stacking direction, the polarization energies of different lengths of the antiparallel π-π stacks vs the inverse of the number of TFDMN molecules are plotted in Fig. 3b. Similarly, the P+ and P- for the infinite 1D stack (N-1 = 0) are extrapolated to -0.383 and -0.272 eV, respectively. Obviously, the polarization energies of the 1D stack are just about one third of those for the bulk material, indicating that the inter-stack electronic polarization effect should be at least taken into account. Consistent with the 3D clusters, the positive charge carrier is more stabilized than the negative charge carrier for the 1D stack. These results suggest that the polarization energies of the TFDMN crystal are not dominated the π-π stacking direction.

To consider the inter-stack contribution, we have added two adjacent stacks along three different directions in the crystal (Fig. S4 in Supporting information), and calculated the polarization energies for these 3-stack models. We can find that the inter-stack polarization effects are very obvious and different along the studied three directions. The 2D-Ⅰ (head-to-tail inter-stack) model has the weakest hole polarization and strongest electron polarization among the three 3-stack models. The hole polarization of the 2D-Ⅱ (side-by-side inter-stack) model is the strongest and nearly as large as twice that of the single stack. The 2D-Ⅱ and 2D-Ⅲ models exhibit similar electron polarization. At the same time, we gradually increase the distances between the adjacent stacks (Fig. 1c). The dependence of the polarization energies for hole and electron on the increased inter-stack distance is shown in Fig. 3c. When the distance is increased by 15 Å, the inter-stack polarization will almost vanish, and the hole and electron polarization energies of the 3-stack models are converged to the values of the single stack.

To fully understand the inter-stack influence, the polarization energies of 2D disks with various radii (Figs. 1d-f) have been calculated and are shown in Figs. 3d-f as a function of the square root of the number of molecules (N-1/2). Clearly, the polarization energies are linearly correlated with the values of N-1/2. Interestingly, with increasing number of molecules, the polarization energy for hole almost remains the same in the case of the 2D-Ⅰ disk, but the electron polarization energy is hardly changed for the 2D-Ⅱ and 2D-Ⅲ disks. For 2D-Ⅱ and 2D-Ⅲ disks, the extrapolated electron polarization energies are almost equivalent (ca. -0.49 eV), and they are weaker than the hole polarization energies (ca. -0.73 and -0.63 eV, respectively). On the contrary, the polarization energy is stronger for electron (ca. -0.57 eV) than hole (ca. -0.49 eV) in the case of the 2D-Ⅰ disk. Apparently, although the polarization energies for the 2D disks are significantly enhanced, they are still weaker than the bulk polarization energy (Fig. 4). Namely, the contributions to the bulk polarization energy along the three dimensions are comparable to each other.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Extrapolated polarization energies for the 1D stack, 2D disks, and 3D cluster. | |

Up to now, we note that the electronic polarization effects of the dipolar TFDMN molecular system are similar to the corresponding nonpolar naphthalene system. Since the TFDMN molecules are antiparallel packed, we have calculated the ESP maps of the antiparallel TFDMN dimer (Fig. 2d). Compared with the single TFDMN molecule, the contrast between the electron-rich and electrondeficient regions of ESP is much decreased and approaches that of the naphthalene's ESP (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). Thus, the dipole moments of TFDMN will be substantially decreased in the antiparallel packing condensed state. Then, the polarization effect will be largely decreased, and especially, every pair of antiparallel TFDMN molecules exhibit as weak polarity as the nonpolar systems.

In summary, using an electron push-pull substituted naphthalene molecule as representative, we have studied the electronic polarization on charge carriers in dipolar molecular semiconductors by a polarizable force field method. It is found that there is no significant difference in polarization energies between the dipolar and nonpolar systems. In addition, the electronic polarization along the π-π stacking direction does not hold the main part of polarization energy, and the contributions to the polarization energy along three dimensions are comparable to each other. This underlines that the electronic polarization along each dimension cannot be ignored. These findings would be helpful for understanding the site energies and charge transport properties in dipolar organic semiconductors.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors acknowledge the support from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. 2017YFA0204502) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDB12020200).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary material related to this article can befound, in the online version, at doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2019.05.024.

| [1] |

V. Coropceanu, J. Cornil, D.A. da Silva Filho, et al., Chem. Rev. 107 (2007) 926-952. DOI:10.1021/cr050140x |

| [2] |

M. Pope, C.E. Swenberg, Electronic Processes in Organic Crystals and Polymers, Oxford University Press, New York, 1999.

|

| [3] |

J.L. Bredas, J.E. Norton, J. Cornil, V. Coropceanu, Acc. Chem. Res. 42 (2009) 1691-1699. DOI:10.1021/ar900099h |

| [4] |

H. Yoshida, K. Yamada, Jy. Tsutsumi, N. Sato, Phys. Rev. B B 92 (2015) 075145. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.92.075145 |

| [5] |

J.E. Norton, J.L. Bredas, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (2008) 12377-12384. DOI:10.1021/ja8017797 |

| [6] |

S.M. Ryno, C. Risko, J.L. Bredas, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 6421-6427. DOI:10.1021/ja501725s |

| [7] |

J. Li, G. D'Avino, I. Duchemin, D. Beljonne, X. Blase, J. Phy. Chem. Lett. 7 (2016) 2814-2820. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b01302 |

| [8] |

S.M. Ryno, Y.T. Fu, C. Risko, J.L. Bredas, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8 (2016) 15524-15534. DOI:10.1021/acsami.6b02851 |

| [9] |

Z. Zheng, J.L. Bredas, V. Coropceanu, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7 (2016) 2616-2621. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00911 |

| [10] |

Z. Yang, Z. Mao, Z. Xie, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 46 (2017) 915-1016. DOI:10.1039/C6CS00368K |

| [11] |

H. Wang, L. Xie, Q. Peng, et al., Adv. Mater. 26 (2014) 5198-5204. DOI:10.1002/adma.201401393 |

| [12] |

R. Bhosale, J. Misek, N. Sakai, S. Matile, Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 (2010) 138-149. DOI:10.1039/B906115K |

| [13] |

H. Buerckstuemmer, E.V. Tulyakova, M. Deppisch, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50 (2011) 11628-11632. DOI:10.1002/anie.201105133 |

| [14] |

O.L. Griffith, X. Liu, J.A. Amonoo, et al., Phys. Rev. B 92 (2015) 085404. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.92.085404 |

| [15] |

X. Shen, G. Han, Y. Yi, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18 (2016) 15955-15963. DOI:10.1039/C6CP02296K |

| [16] |

X. Xu, G. Zhang, Y. Li, Q. Peng, Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 809-825. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.02.030 |

| [17] |

Z. Wen, X. Ma, X. Yang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 995-999. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.01.028 |

| [18] |

Y. Li, Y. Xu, F. Yang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 222-224. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2018.09.014 |

| [19] |

X. Che, Y. Li, Y. Qu, S.R. Forrest, Nat. Energy 3 (2018) 422-427. DOI:10.1038/s41560-018-0134-z |

| [20] |

B. Fan, D. Zhang, M. Li, et al., Sci. China Chem. 62 (2019) 746-752. DOI:10.1007/s11426-019-9457-5 |

| [21] |

L. Meng, Y. Zhang, X. Wan, et al., Science 361 (2018) 1094-1098. DOI:10.1126/science.aat2612 |

| [22] |

Z.F. Yao, J.Y. Wang, J. Pei, Cryst. Growth Des. 18 (2018) 7-15. DOI:10.1021/acs.cgd.7b01385 |

| [23] |

J. Vura-Weis, M.A. Ratner, M.R. Wasielewski, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 1738-1739. DOI:10.1021/ja907761e |

| [24] |

L. Huang, M. Stolte, H. Bürckstümmer, F. Würthner, Adv. Mater. 24 (2012) 5750-5754. DOI:10.1002/adma.201202441 |

| [25] |

M. Gsaenger, E. Kirchner, M. Stolte, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 2351-2362. DOI:10.1021/ja409496r |

| [26] |

C. Wang, H. Dong, L. Jiang, W. Hu, Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (2018) 422-500. DOI:10.1039/C7CS00490G |

| [27] |

X. Zhang, X. Chen, J. Liu, et al., Sci. China Chem. 59 (2016) 1645-1650. DOI:10.1007/s11426-016-0098-y |

| [28] |

S.M. Ryno, C. Risko, J.L. Bredas, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8 (2016) 14053-14062. DOI:10.1021/acsami.6b02579 |

| [29] |

C.M. Kane, T.B. Meyers, X. Yu, M. Gerken, M. Etzkorn, Eur. J. Org. Chem. (2011) 2969-2980. |

| [30] |

L. Wang, G. Nan, X. Yang, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 (2010) 423-434. DOI:10.1039/B816406C |

| [31] |

P. Ren, J.W. Ponder, J. Comput. Chem. 23 (2002) 1497-1506. DOI:10.1002/jcc.10127 |

| [32] |

P. Ren, J.W. Ponder, J. Phys. Chem. B 107 (2003) 5933-5947. DOI:10.1021/jp027815+ |

| [33] |

J.W. Ponder, C. Wu, P. Ren, et al., J. Phys. Chem. B 114 (2010) 2549-2564. DOI:10.1021/jp910674d |

| [34] |

X. Zhao, T. Xu, S. Yin, Chem. Phys. 516 (2019) 84-91. DOI:10.1016/j.chemphys.2018.08.027 |

| [35] |

P.Y. Ren, J.W. Ponder, J. Phy. Chem. B 108 (2004) 13427-13437. DOI:10.1021/jp0484332 |

| [36] |

T. Xu, S. Yin, Sci. China Chem. 57 (2014) 1375-1382. |

| [37] |

N.R. Tummala, Z. Zheng, S.G. Aziz, V. Coropceanu, J.L. Bredas, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6 (2015) 3657-3662. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01709 |

| [38] |

M.J. Frisch, G.W. Trucks, H.B. Schlegel, et al., Gaussian 09, Revision E.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2013.

|

| [39] |

B.T. Thole, Chem. Phys. 59 (1981) 341-350. DOI:10.1016/0301-0104(81)85176-2 |

| [40] |

P.T. van Duijnen, M. Swart, J. Phys. Chem. A 102 (1998) 2399-2407. DOI:10.1021/jp980221f |

| [41] |

A. Grossfield, P.Y. Ren, J.W. Ponder, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 (2003) 15671-15682. DOI:10.1021/ja037005r |

| [42] |

S.M. Ryno, S.R. Lee, J.S. Sears, C. Risko, J.L. Bredas, J. Phy. Chem. C 117 (2013) 13853-13860. DOI:10.1021/jp402991z |

| [43] |

G. D'Avino, L. Muccioli, C. Zannoni, D. Beljonne, Z.G. Soos, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10 (2014) 4959-4971. DOI:10.1021/ct500618w |

| [44] |

T. Xu, W. Wang, S. Yin, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 14 (2018) 3728-3739. DOI:10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00132 |

2020, Vol. 31

2020, Vol. 31