b Department of Advanced Materials Science, Kagawa University, Takamatsu, Kagawa 761-0396, Japan

Benzimidazole is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound and particularly important in pharmaceutical chemistry [1]. Numbers of methods have been applied for the synthesis of benzimidazole derivatives so far [2], including reactions of 1, 2-phenylenediamines with carboxylic acids, its derivatives [3], or aldehydes [4], whereas there are serious problems such as co-production of toxic wastes and low atom efficiencies. Methods using transition metal-catalyzed reactions such as carbonylation of 1, 2-phenylenediamine followed by cyclodehydration [5], and intramolecular N-arylation reaction of (o-bromophenyl)amidines [6] were also reported.

Among these methods, dehydrogenation between primary alcohols and derivatives of 1, 2-phenylenediamine is one of the most straightforward and environmentally-benign synthetic routes, since only water and two equivalents of molecular hydrogen are liberated. Kondo and co-workers reported a successful example catalyzed by a ruthenium phosphine complex, namely RuCl2(PPh3)3 [7]. However, this process requires harsh conditions, such as a high reaction temperature as 200 ℃. Afterwards, the reaction catalyzed by Ru(PPh3)3(CO)H2 in combi-nation with a Xantphos ligand was reported to smoothly proceed in refluxing toluene, but an excess amount of crotononitrile was equired as a hydrogen acceptor [8]. Acceptorless reactions were reported to be realized in the presence of an iridium complex stabilized by a tridentate P^N^P ligand together with a stoichio-metric amount of strong base [9]. Recently, Milstein and co-workers reported cobalt-catalyzed acceptorless reactions operated at 150 ℃ [10]. However, homogeneous catalysts have several inherent disadvantages in terms of the development of environ-mentally-benign processes, such as the difficulty of recovering and recycling the catalysts after the reaction.

The use of solid catalysts can overcome these problems. Therefore, much attention has been focused on synthetic processes with supported metal catalysts [11, 12]. The authors have devel-oped a series of ceria-supported ruthenium [11g, h] and rhodium [13] catalysts which enable various highly atom-efficient organic transformations.

Herein, the mini review provides examples of supported transition metal catalysts for the synthesis of benzimidazoles from 1, 2-phenylenediamines and primary alcohols. The oxidative synthesis of 2-phenylbenzimidazole (3aa) was achieved at 80 ℃ via tandem reactions of the oxidation of benzyl alcohol (2a), double condensation with phenylenediamine (1a), and amine oxidation in the presence of a ruthenium hydroxide catalyst supported on anatase (JRC-TIO-1, supplied from the Catalysis Society of Japan) [14] (Scheme 1a). The synthesis of benzimidazoles by simulta-neous photocatalytic oxidation of alcohol and catalytic dehydro-genation of the intermediates on Pt-modified titania nanoparticles (JRC-TIO-4, equivalent to Degussa P25) has been demonstrated at room temperature under UV irradiation (λ>300 nm) [15] (Scheme 1b). Various primary alcohols including ethanol and benzyl alcohol were applicable and the desired products were selectively produced.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme1. Examples of the synthesis of benzimidazoles by titania-supported transition metal catalysts [14-16]. | |

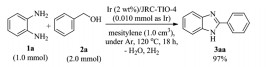

Remarkably, Shimizu and co-workers have compared the activity of various supported transition metal catalysts for the dehydrogenative synthesis of 2-substituted benzothiazoles and benzimidazoles directly from primary alcohols in refluxing mesitylene without acceptors and additives. They reported the excellent activity of Pt/TiO2 (JRC-TIO-4) catalyst [16] (Scheme 1c): Ir/TiO2 was also effective under these conditions.

Following these reports on the titania-supported catalysts and our works shown below [17], successful examples using solid catalysts, such as Co3O4@Al2O3/SiO2 in air or O2 [18a], Pd/Cu-MOF with a base [18b], Ru/N-doped carbon with KOH [18c], Mg-modified Cu-Pd/λ-Al2O3 [18d], and polystyrene-supported rhodi-um with a base [18f], were reported. Recent progresses were also summarized in a review by Shimizu et al. [12].

The present authors focused their efforts on the development of supported transition-metal catalysts which realize acceptorless dehydrogenative synthesis of benzimidazoles at relatively low temperatures. As shown in Fig. 1, the comparison of the activity of the supported catalysts clearly revealed the dominance of iridium catalysts to Pd, Rh and Ru ones at 120 ℃. As a support for the iridium catalyst, titania (JRC-TIO-4) was found to be most excellent (reaction (1)) [17a].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Effects of metallic species and supports on the synthesis of 3aa at 120 ℃, 18 h[17a] | |

|

(1) |

In the reaction at a higher substrate-to-catalyst ratio (S/C=1000), a high turnover number (TON) over 800 was achieved. This titania-supported iridium catalyst was applicable to the reactions of various primary alcohols and derivatives of 1, 2-phenylenediamine as shown in Fig. 2. Not only benzylic alcohols, but simple aliphatic alcohol (2g) could be used also.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Scope of substrates for the reaction at 120 ℃ for 18 h catalyzed by Ir(2.0 wt %)/ JRC-TIO-4. Reaction conditions are shown in reaction (1) | |

The present catalysts maintained its excellent activity until the 3rd use. After the removal of the solid catalyst by hot filtration, further conversion of 1a was completely stopped, which clearly indicates that the solid catalyst acted heterogeneously. ICP-AES analysis revealed that the leaching of iridium species into the reaction mixture was almost negligible: 0.000022 mmol(0.22 mol% of the iridium species in the fresh catalyst). These results evidence that this reaction proceeded on the surface of the solid catalyst.

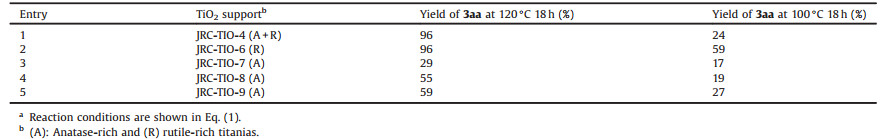

As shown in Table 1,titania used as a support significantly affect the low-temperature activity of the iridium catalyst [17b]. While the catalysts supported on anatase showed moderate to poor activity at 100 ℃, the reaction in the presence of rutile-supported catalysts smoothly proceeded to give 3aa in high yields. The activity of JRC-TIO-6-supported one further improved to give 3aa in 88% yield when the catalyst was prepared without the calcination procedure prior to the reduction in an H2 flow.

|

|

Table 1 Effects of JRC titania supports.a |

Dehydrogenative conversion of 2-(2-aminophenyl)ethanol to indole also shows similar dependency on titania. The reaction at 100 ℃ for 18 h in the presence of 1.0 mol% iridium on rutile gave indole in a yield of 73%, while the use of anatase-supported catalysts resulted in poor yields.

TEM images show that iridium species were not homogeneous-ly loaded on anatase such as F-2 (anatase delivered from Showa Denko Ceramics Co., Ltd., Fig. 3a)]. There are dense iridium nanoparticles on some specific facets of the titania particles but not on other facets. Such uneven loading of noble metallic species on TiO2 has been reported, especially by the photo-deposition [19]. The formation of small iridium nanoparticles (ca. 1 nm to 2 nm in diameter) was observed for the highly-active JRC-TIO-6-supported catalyst (Fig. 3b), but iridium nanoparticles of Ir/JRC-TIO-7 of poor low-temperature activity was smaller (Fig. 3c). These results suggest that not only the iridium particle size but other factors might govern the catalytic activity.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. TEM images of the Ir catalysts(2 wt%) supported on (a) F-2, (b) JRC-TIO-6, and (c) JRC-TIO-7 [17b]. | |

On the other hand, there is a significant relationship between CO uptake and the activity of titania-supported catalysts as summarized in Fig. 4. In general, iridium on rutile adsorbed much amount of CO and showed higher activity at 100 ℃. The investigation by XPS indicates that fully-reduced iridium species are predominant on rutile titanias. The formation of well-reduced iridium species on rutile would be one reason for both the predominant catalytic activity and CO uptake ability. Recently, the superior activity of iridium catalyst supported on rutile for high-concentration N2O decomposition to those of anatase- or γ-alumina-supported catalysts was reported [20]. Similar to our study, XPS study revealed that the iridium species on rutile were more electron rich in comparison with iridium on other support. A characteristic charge transfer to noble metal nanoclusters from a rutile support could be one reason for the formation of electron rich species [21].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Relationship between CO uptake (mol/Ir-mol) by the catalysts and the yield of 3aa at 100 ℃. *Prepared without calcination. **Prepared using [(COD)IrCl]2 as an iridium source. | |

As proposed previously [15-17], the acceptorless dehydrogenative synthesis of benzimidazoles is considered to be initiated by the oxidation of alcohol by the metallic catalyst to form corresponding aldehydes, followed by the condensation with 1, 2-phenylenediamines and the final metal-catalyzed dehydroge-nation. A kinetic study on Pt-catalyzed reaction indicates that the dehydrogenation of alcohols is the slow step [15]. Interestingly, the dehydrogenation from 2a to benzaldehyde by Ir/JRC-TIO-4 is much slower than the reaction of 2a with 1a. In addition, the presence of benzaldehyde almost completely inhibited the dehydrogenation of 2a, suggesting the poisoning effect of benzaldehyde on the iridium catalysis [17a]. This benzaldehyde would be smoothly removed from the iridium sites by the successive reaction with 1a.Understanding of the reaction mechanisms of such multiple catalytic transformations is indispensable to design a suitable catalyst. Therefore, further application of in situ measurement technique [22] for such mechanistic study is highly expected.

Note that titania-supported iridium catalysts with ultralow iridium loading (ca.0.05 wt%) were reported to be excellent for the synthesis of quinolines from nitroarenes and aliphatic alcohols via hydrogen transfer [23]: Sub-nano-sized iridium clusters formed on the surface were reported to be responsible for the excellent activity. Therefore, the authors prepared such low-loading catalysts, but they were not very effective for the dehydrogenative benzimidazole synthesis. This indicates significant differences in the iridium species suitable for dehydrogenative reactions and those via hydrogen transfer.

In this review, the recent development of titania-supported iridium catalysts for the title reaction by the authors and related works by other researchers are briefly summarized. These catalysts are promising for the synthesis of not only benzimidazole derivatives but also a wide range of useful chemicals, while further efforts should be paid for the improvement of the stability of the catalysts. The results shown here suggest the importance of the selection of suitable titania supports for the iridium catalysts.

AcknowledgmentThis research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (No. JSPS, 17H03458).

| [1] |

(a) D.A. Horton, G.T. Bourne, M.L. Smythe, Chem. Rev. 10 (2003) 893–930; (b) M. Salahuddin, M. Shaharyar, A. Mazumder, Arabian J. Chem. 10 (2017) 5157–5173 and references therein. |

| [2] |

(a) J.B. Wright, Chem. Rev. 48 (1951) 397–541; (b) P.N. Preston, Chem. Rev. 74 (1974) 279–314; (c) M. Curini, F. Epifano, F. Montanari, O. Rosati, S. Taccone, Synlett (2004) 1832–1834; (d) J. Zhu, Z. Zhang, C. Miao, W. Liu, W. Sun, Tetrahedron 73 (2017) 3458–3462 and references therein. |

| [3] |

E. Alcalde, I. Dinares, L.P. Garcia, T. Roca, Synthesis (1992) 395–398. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240855791_ChemInform_Abstract_An_Advantageous_Synthesis_of_2-Substituted_Benzimidazoles_Using_Polyphosphoric_Acid_2-Pyridyl-1H-benzimidazoles_1-Alkyl-1H-_benzimidazol-2-ylpyridinium_Salts_Their_Homologues_and_V

|

| [4] |

P. Sun, Z. Hu, J. Heterocyclic Chem. 43 (2006) 773-775. DOI:10.1002/jhet.5570430338 |

| [5] |

R.J. Perry, B.D. Wilson, J. Org. Chem. 58 (1993) 7016-7021. DOI:10.1021/jo00077a019 |

| [6] |

C.T. Brain, S.A. Brunton, Tetrahedron Lett. 43 (2002) 1893-1895. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00132-6 |

| [7] |

T. Kondo, S. Yang, K. Huh, et al., Chem. Lett. 1275-1278. |

| [8] |

A.J. Blacker, M.M. Farah, M.I. Hall, et al., Org. Lett. 11 (2009) 2039-2042. DOI:10.1021/ol900557u |

| [9] |

T. Hille, T. Irrgang, R. Kempe, Chem. -Eur. J. 20 (2014) 5569-5572. DOI:10.1002/chem.201400400 |

| [10] |

P. Daw, Ben-David Y., D. Milstein, ACS Catal. 7 (2017) 7456-7460. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b02777 |

| [11] |

(a) P. Laszlo, Acc. Chem. Res. 19 (1986) 121–127; (b) Y. Izumi, M. Onaka, Adv. Catal. 38 (2018) 245–282; (c) K. Kaneda, Synlett (2007) 999–1015; (d) M. Tada, Y. Iwasawa, Coord. Chem. Rev. 251 (2007) 2702–2716; (e) L. Yin, J. Liebscher, Chem. Rev. 107 (2007) 133–173; (f) A. Corma, H. Garcia, Chem. Soc. Rev. 37 (2008) 2096–2126; (g) K. Wada, S. Hosokawa, M. Inoue, Catal. Surv. Asia 15 (2011) 1–11; (h) K. Wada, H. Miura, S. Hosokawa, M. Inoue, J. Jpn. Petro. Inst. 56 (2013) 69– 79. |

| [12] |

S.M.A.H. Siddiki, T. Toyao, K. Shimizu, Green Chem. 20 (2018) 2933-2952. DOI:10.1039/C8GC00451J |

| [13] |

S. Tsukada, K. Wada, H. Miura, et al., Res. Chem. Intermed. 41 (2015) 9575-9586. DOI:10.1007/s11164-015-1983-8 |

| [14] |

J.W. Kim, J. He, K. Yamaguchi, N. Mizuno, Chem. Lett. 38 (2009) 920-921. DOI:10.1246/cl.2009.920 |

| [15] |

Y. Shiraishi, Y. Sugano, S. Tanaka, T. Hirai, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (2010) 1656-1660. DOI:10.1002/anie.200906573 |

| [16] |

C. Chaudhari, S.M.A.H. Siddiki, K. Shimizu, Tetrahedron Lett. 56 (2015) 4885-4888. DOI:10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.06.073 |

| [17] |

(a) K. Tateyama, K. Wada, H. Miura, et al., Catal. Sci. Technol. 6 (2016) 1677–

1684;

(b) T. Fukutake, K. Wada, G.C. Liu, S. Hosokawa, Q. Feng, Catal. Today 303 (2018)235–240.

|

| [18] |

(a) P.L. Reddy, R. Arundhathi, M. Tripathi, et al., Chem. Select 2 (2017) 3889–

3895; (b) J. Mokhtaria, A.H. Bozcheloei, Inorg. Chim. Acta 482 (2018) 726–731; (c) B. Guo, H.X. Li, S.Q. Zhang, D.J. Young, J.P. Lang, ChemCatChem 10 (2018) 5627–5636; (d) F. Feng, Y. Deng, Z. Cheng, et al., Catalysts 9 (2019) 8–18; (e) C. Baumler, R. Kempe, Chem. -Eur. J. 24 (2018) 8989–8993; (f) S. Sharma, A. Sharma, P.Das Yamini, Adv. Synth. Catal. 361 (2019) 67–72. |

| [19] |

(a) T. Ohno, K. Sarukawa, M. Matsumura, New J. Chem. 26 (2002) 1167–1170;

(b) D. Sun, W. Yang, L. Zhou, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 182 (2016) 85–93.

|

| [20] |

S. Liu, N. Tang, Q. Shang, et al., Chin. J. Catal. 39 (2018) 1189-1193. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2067(18)63077-3 |

| [21] |

A. Visikovskiy, K. Mitsuhara, Y. Kido, J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 31 (2013) 061404. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260707629_Role_of_gold_nanoclusters_supported_on_TiO2110_model_catalyst_in_CO_oxidation_reaction?ev=auth_pub

|

| [22] |

L. Wang, W. Zhang, X. Zheng, J. Zeng, et al., Nat. Energy 2 (2017) 869-876. DOI:10.1038/s41560-017-0015-x |

| [23] |

L. He, J.Q. Wang, Y. Gong, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50 (2011) 10216-10220. DOI:10.1002/anie.201104089 |

2020, Vol. 31

2020, Vol. 31