b School of Energy Science and Engineering & Institute for Advanced Materials, Nanjing Tech University, Nanjing 211816, China

Supercapacitors with attractive high power density, rapid charge and discharge and long cycling life have attracted increasing research attentions. As the key components for supercapacitors, electrode materials with high specific capacitance, good rate performance and stable cycling have been widely investigated [1-4]. Porous carbons are one of the widely explored candidates due to their large specific surface area, rich porosity, high electron conductivity and ultrashort charge-discharge time, which is closely related to their energy storage mechanism, i.e., electric double layer instead of Faradaic process [1, 2]. However, supercapacitors based on porous carbon materials show limited energy density, and then focus is turned into the investigation of pseudocapacitive materials based on the charge-transfer Faradaic reactions, i.e., redox reactions, such as oxides and sulfides [3, 4].

The fast reversible redox reactions, and/or ion intercalation/deintercalation reactions occurring on the shallow surface are supposed to be responsible for high pseudocapacitance [4]. Consequently, nanoscale materials with diverse unique morphology such as hollow structure [4-6], core-shell design [7] and nanosheets [8] holding higher specific surface area compared to their bulk counterparts have been widely explored. On the other side, general pseudocapacitive materials such as metal oxides or sulfides show poor electron conductivity and/or limited cycling stability, which greatly limit their electrochemical performance and practical applications. The introduction of conductive agents such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [9, 10] and graphene [4, 11, 12] enables the remarkable improvement of the electrochemical performance by increasing the electronic conductivity and preventing the collapse of nanostructures during repeated cycling process.

Recently, metal organic framework (MOF) compounds, due to their high specific surface area, controllable abundant porous structure and simple synthesis methods, were investigated for energy storage applications [4, 13-15]. For example, a composite of nanoporous Co3O4 and carbon with high capacitance was synthesized by a single MOF and ZIF-67 (zeolitic imidazolate framework) was used to prepare electrode materials for supercapacitors with a high capacitance of 504 F/g [16]. The metal sulfides with hollow structure possessing high specific area and ordered porous structure was synthesized via sulfidation of MOF [5, 17, 18]. These hollow particles show better electrochemical performance compared with their bulk materials. However, they still present poor conductivity. Recent work showed that sandwich-like cobalt sulfide based on reduced graphene oxides (rGO) shows high cycling stability with 99.7% capacitance retention after 4000 cycles [12].

Herein, we reported a simple hydrothermal method to prepare a composite of rGO with hollow Co9S8 particles from the reaction of uniform ZIF-67 nanoparticles with thioacetamide and results show that they can be used as superior electrode materials for supercapacitors.

The synthetic procedure of this composite, Co9S8/rGO, is illustrated in Fig. 1a and details are shown in Supporting information. Firstly, GO was prepared via a chemically modified method [19]. Then, ZIF-67 was prepared by mixing the 2-methylimidazole (2-MI) solution and cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O), and kept still for 24 h. Monodispersed ZIF-67 with average diameter of 200-300 nm was prepared (Fig. 1b). In the case of the preparation of GO/ZIF-67, beside the addition of GO after adding 2-MI, the process was similar to that of ZIF-67. The obvious composite with uniform ZIF-67 attached to both sides of GO was achieved after the addition of GO [20]. As shown in Fig. 1c, a composite of perfect monodispersed dodecahedron of ZIF-67 supported on GO was prepared. The obtained GO/ZIF-67 composite was dispersed in ethanol solution by ultrasonic treatment, followed by adding thioacetamide (TAA). After hydrothermal reaction at 120 ℃ for 3 h in a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, the obtained precipitate was annealed at 500 ℃ in argon atmosphere for 2 h. A composite of rGO with hollow Co9S8 particles was successfully prepared (Fig. 1d).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of the preparation process of rGO/Co9S8 (a) and SEM images of synthesized materials in each process: (b) ZIF-67, (c) GO/ZIF-67, and (d) rGO/Co9S8. Scale bar: (a) 3μm, (b) 1μm, (c) 3 μm. | |

Magnified SEM image of ZIF-67 (Fig. 2a) show clearly that it exists as dodecahedron particles and there is little change in shape from the initial ZIF-67, and that of Co9S8 exists as hollow particles (Fig. 2b). Some broken particles also verified the hollow structure of the prepared Co9S8. Noteworthy, the average diameter of the obtained Co9S8 is enlarged after the sulfidation, which can be explained by the different diffusion speed of metal ion and sulfur ion. During the sulfidation procedure, the sulfur ion dissolved from TAA diffused to the surface of the ZIF-67 and combine the cobalt ion to form a hollow Co9S8. Due to the large diameter of sulfur ion it is difficult to move inward. As a result, the smaller cobalt ion moved outward to form cobalt sulfide. Therefore, the inner side of the ZIF-67 particles becomes empty and a hollow Co9S8 is achieved (Fig. S1 in Supporting information). As shown in Fig. 2c, powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns for both ZIF-67 and GO/ZIF-67 show typical ZIF topologies, and no peak of GO is observed because of its low intensity. The XRD patterns of Co9S8 and rGO/Co9S8 (Fig. 2d) show the characteristic peaks of (311), (222), (331), (511) and (440) planes for the cobalt pentlandite (JCPDS No. 86-2273, Co9S8) at 2θ values of 29.8°, 31.2°, 39.6°, 47.6° and 52.1°, respectively. Raman spectra (Fig. S4 in Supporting information) show a clear evidence of the presences of graphene in the composites. Raman peaks at 1361.2 cm-1 and 1603.2 cm-1 could be ascribed to disordered carbon-induced D band and graphitic carbon related G band of rGO/Co9S8, respectively.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. SEM images of ZIF-67 (a) and Co9S8 (b), XRD patterns of ZIF-67 and GO/ZIF-67 (c), and Co9S8 and rGO/Co9S8 (d). | |

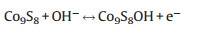

For cobalt sulfide-based electrode in alkaline solution (1 mol/L KOH), the Faradaic reactions are suggested as the following equations [21]:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

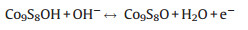

Fig. 3a shows the representative cyclic voltammetric (CV) curves of the rGO/Co9S8 at various scan rates in the potential range of 0–0.55 V (vs. saturated calomel electrode, SCE). All of the curves show clear pseudocapacitance features with a similar shape, an evident oxidation peak and a large reduction one, which correspond to the reactions suggested in Eqs. (1) and (2). The curves maintained regular shapes even at a high scan rate of 100 mV/s, indicating the superb high-rate performance of rGO/Co9S8. To compare the functions of the added rGO, their CV curves at a scan rate of 10 mV/s are shown in Fig. 3b. The higher area of the closed CV curve of the rGO/Co9S8 indicates its higher activities for the redox reactions due to the presence of rGO. When the current density increases from 2 A/g to 10 A/g in the potential window from 0 to 0.45 V (Fig. 3c), there are no obvious potential plateaus, which are similar to those of supercapacitors and different from those of batteries [4, 22]. Due to the existence of pseudocapacitance from the redox reactions of Eqs. (1) and (2), their charge and discharge curves are not linearly symmetric [4]. The capacitances of the electrodes were calculated from the following Eq. (3):

|

(3) |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. CV curves of (a) rGO/Co9S8 at different scan rates and (b) Co9S8 and rGO/Co9S8 at the scan rate of 10 mV/s, (c) charge-discharge curves of rGO/Co9S8, (d) rate performance, (e) EIS spectra and equivalent circuits, and (f) cycling performance of Co9S8 and rGO/Co9S8. | |

where Cs is the specific capacitance (F/g), I is the discharge current (A), dt is the differential of discharge time, m is the mass of the active materials (g) and dV (V) is the differential of potential. The rGO/Co9S8 electrode shows a specific capacitance of 575.9, 526.0, 493.7, 467.2 and 447.7 F/g at a current density of 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 A/g, respectively (Fig. 3d). The IR drop of the curves resulting from fast accumulation of charges and reactions during the charge/discharge process is relatively low even at a large current density of 10 A/g. The specific capacitance of the rGO/Co9S8 retains 59.9% with the current density ranging from 1 A/g to 20 A/g. This is illustrated from the EIS spectra of Co9S8 and the rGO/Co9S8, and their corresponding equivalent circuits shown in Fig. 3e. The resistance of the system (Rs), including the ohmic resistance of electrolyte interfaces and the active materials, are 0.5Ω in rGO/Co9S8 and 1.34Ω in Co9S8. This decrease is mainly resulted from the good electronic conductivity introduced by rGO. The charge transference resistance (Rct) is only 0.89Ω after the addition of rGO, which is dramatically decreased compared with that of Co9S8, 2.16Ω. The diffusion resistances (RD), indicating the migration rate of ions from the electrolyte inside the surface of Co9S8, are 1.26Ω and 1.07Ω for Co9S8 and rGO/Co9S8, respectively. This result is consistent with the above results such as excellent rate performance.

As shown in Fig. 3f, the rGO/Co9S8 exhibited a remarkable good capacitance retention of 92.0% after 9000 cycles at a current density of 4 A/g. In contrast, Co9S8 remained only 82.7% at the same condition and its reversible capacitance is also lower than that of rGO/Co9S8.

The excellent performances are mainly ascribed to the following three factors: (ⅰ) An electronic pathway is introduced by the rGO substrate. Consequently, the charge transfer resistance of the rGO/Co9S8 is smaller than that of Co9S8, which leads to higher output power. (ⅱ) The hollow structure with its high specific surface area lowers the ion transportation distance. Due to the high surface area, the contact area between activated material and electrolyte is largely increased. Higher contact area could reduce the ion transportation distance and enhance the efficiency of ion transporting, which benefits the good high-rate performance and larger capacitance. (ⅲ) The added rGO supports the Co9S8 hollow particle during the cycling, which promotes the cycling stability. The rGO can prevent Co9S8 from collapsing during fast charge and discharge process. The SEM image of the rGO/Co9S8 after the cycling shows the relative better retention of hollow structure than that of Co9S8 (Fig. S5 in Supporting information), in spite of the inevitable slight collapsing in the rGO/Co9S8. Actually, this unique hollow Co9S8 on rGO is generally valid for other materials, such as hollow ZnS particle derived from ZIF-8 [23] and Fe2O3 microboxes derived from Prussian blue [24].

In summary, we demonstrate an approach to fabricate a composite of hollow Co9S8 on rGO, in which the hollow Co9S8 is derived from the sulfidation of ZIF-67. The obtained rGO/Co9S8 exhibits excellent electrochemical performance including high specific capacitance of 575.9 F/g at 2 A/g, excellent high-rate capability of 447.7 F/g at 10 A/g and good cycling stability with 92.0% capacitance retention after 9000 cycles at 4 A/g. The outstanding electrochemical performance can be explained by the elaborately designed structure. We analyzed and summarized the relational advantages of this unique structure, and believed it could be generally extended to other hollow materials. Further work on the influence of the rGO content is needed while the insufficient and excessive addition both have negative effect on electrochemical performance. This work paved a way to design the composite structure combining rGO and nanohollow materials such as metal sulfides and oxides.

AcknowledgmentsFinancial support from National Key Project (No. 2017YFF0210703), Distinguished Young Scientists Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51425301, 21374021, 51673096 and U1601214) and Sanyo Chemical Co., Ltd. is gratefully appreciated.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2018.01.051.

| [1] |

F.X. Wang, S.Y. Xiao, Y.Y. Hou, et al., RSC Adv. 3 (2013) 13059-13084. DOI:10.1039/c3ra23466e |

| [2] |

M. Winter, R.J. Brodd, Chem. Rev. 104 (2004) 4245-4269. DOI:10.1021/cr020730k |

| [3] |

B.E. Conway, W.G. Pell, J. Solid State Electrochem. 7 (2003) 637-644. DOI:10.1007/s10008-003-0395-7 |

| [4] |

F.X. Wang, X.W. Wu, X.H. Yuan, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 46 (2017) 6816-6854. DOI:10.1039/C7CS00205J |

| [5] |

X.Y. Yu, L. Yu, X.W.D. Lou, Adv. Energy Mater. 6 (2016) 1501333. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201501333 |

| [6] |

M. Xu, L. Kong, W. Zhou, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 111 (2007) 19141-19147. DOI:10.1021/jp076730b |

| [7] |

X. Lu, M. Yu, G. Wang, et al., Adv. Mater. 25 (2013) 267-272. DOI:10.1002/adma.201203410 |

| [8] |

M. Acerce, D. Voiry, M. Chhowalla, Nat. Nanotechnol. 10 (2015) 313-318. DOI:10.1038/nnano.2015.40 |

| [9] |

J. Yan, Z. Fan, T. Wei, et al., J. Power Sources 194 (2009) 1202-1207. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.06.006 |

| [10] |

C. Peng, S. Zhang, D. Jewell, et al., Prog. Nat. Sci. 18 (2008) 777-788. DOI:10.1016/j.pnsc.2008.03.002 |

| [11] |

X.C. Dong, H. Xu, X.W. Wang, et al., ACS Nano 6 (2012) 3206-3213. DOI:10.1021/nn300097q |

| [12] |

Y. Wang, B. Chen, Z. Chang, J. Mater. Chem. A 5 (2017) 8981-8988. DOI:10.1039/C7TA01500C |

| [13] |

H. Li, M. Eddaoudi, M. O'Keeffe, et al., Nature 402 (1999) 276-279. DOI:10.1038/46248 |

| [14] |

D.Y. Lee, S.J. Yoon, N.K. Shrestha, et al., Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 153 (2012) 163-165. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.12.040 |

| [15] |

A. Morozan, F. Jaouen, Energy Environ. Sci. 5 (2012) 9269-9290. DOI:10.1039/c2ee22989g |

| [16] |

R.R. Salunkhe, J. Tang, Y. Kamachi, et al., Acs Nano 9 (2015) 6288-6296. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.5b01790 |

| [17] |

X.Y. Yu, L. Yu, B.H. Wu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 5331-5335. DOI:10.1002/anie.201500267 |

| [18] |

Z. Jiang, W. Lu, Z. Li, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 2 (2014) 8603-8606. DOI:10.1039/C3TA14430E |

| [19] |

A. Fasolino, J.H. Los, M.I. Katsnelson, Nat. Mater. 6 (2007) 858-861. DOI:10.1038/nmat2011 |

| [20] |

L. Jiao, Y.X. Zhou, H.L. Jiang, Chem. Sci. 7 (2016) 1690-1695. DOI:10.1039/C5SC04425A |

| [21] |

J. Yu, H. Wan, J. Jiang, et al., J. Electrochem. Soc. 161 (2014) A996-A1000. DOI:10.1149/2.053406jes |

| [22] |

Z. Chang, Y.Q. Yang, M.X. Li, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 2 (2014) 10739-10755. DOI:10.1039/C4TA00565A |

| [23] |

Z. Jiang, H. Sun, Z. Qin, et al., Chem. Commn. 48 (2012) 3620-3622. DOI:10.1039/c2cc00004k |

| [24] |

L. Zhang, H.B. Wu, S. Madhavi, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134 (2012) 17388-17391. DOI:10.1021/ja307475c |

2018, Vol. 29

2018, Vol. 29