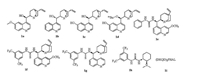

The heterocyclic thiophenes are attractive targets in organic synthesis because the thiophene ring system constitutes the core structural element found in a large family of natural products and unnatural compounds exhibiting highly pronounced biological activities [1] as well as wide-ranging utility as synthetic intermediates for pharmaceutical agents [2], agricultural chemicals [3], dyes [4] and materials [5]. Among them, the chiral highly functionalized dihydrothiophenes are of considerable interest as they possess a wide range of biological properties [6] as well as they could serve as building blocks for new chiral ligands in asymmetric metal catalysis [7], chiral organocatalyst [8] and natural product synthesis, as shown in Fig. 1. For example, the analogues of penicillins which contain chiral tetrahydrothiophene ring system have strong antibacterial activity [9]. Salacinol, which was isolated from an antidiabetic Ayurvedic traditional medicine, is a most potent natural α-glucosidase inhibitor [10]. Biotin is a water-soluble B-vitamin and it is very important in fatty acid synthesis, branched-chain amino acid catabolism, and gluconeogenesis [11]. Moreover, chiral tetrahydrothiophenes appeared to be efficient organocatalysts for the asymmetric reaction, such as asymmetric epoxidation [8].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. The important compounds which contain chiral dihydrothiophene unit. | |

The importance of numerous applications of chiral thiophenes in these areas has led to a demand for efficient synthetic methods for the synthesis of the thiophenes, particularly those producing optically active thiophenes [12]. And a few elegant transformations have been developed for the construction of these optically active structural skeletons, which usually employ either enantiopure starting materials or thiols or multistep reactions to construct these skeletons [12, 13]. Although these were elegant and creative strategies toward the thiophene architecture, the stereoselective synthesis of chiral dihydrothiophenes and tetrahydrothiophenes with high atomic efficiency and good feasibility to assemble various substitution patterns is still highly desirable. Here we report the development of a new organocatalytic Michael/ cyclization domino reaction for the synthesis of regio-, chemo-, diastereo-and enantiomerically pure 4, 5-dihydrothiophenes, building up highly substituted 4, 5-dihydrothiophenes in one step.

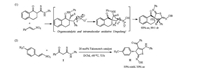

In the past few years, many efforts have been made on the development of novel and practical asymmetric domino reactions through organocatalyzed 1, 3-dicarbonyl compounds activation providing five-membered heterocycles in our group [14]. And we have recently successfully constructed the optically active multifunctional spiroannulated dihydrothiophenes and spiroannulated 1, 2, 3-thiadiazole derivatives with high yields and enantioselectivities via an umpolung strategy from the thioamides (Scheme 1, eq.1) [13]. When the acyclic thioamide Ⅰ was utilized as Michael donor in the reaction with nitroalkene, however, the monocyclic dihydrothiophene Ⅱ was isolated with poor enantioselectivity (33% ee, Scheme 1, eq. 2), even catalyzed by other organocatalysts 1a-1i (Fig. 2). In order to get the optically active monocyclic dihydrothiophenes, we envisioned that maybe other acyclic thioamides with different groups afford good results. As such, the acyclic thioamide 2a with a ester group was firstly prepared and Table 1 showed some screening results for the construction the optically active monocyclic dihydrothiophenes via a thio[3 + 2] cyclization of the acyclic thioamide 2a with (E)-α-nitrostyrene 3a.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Previous work. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Structures of organocatalysts 1a-i. | |

|

|

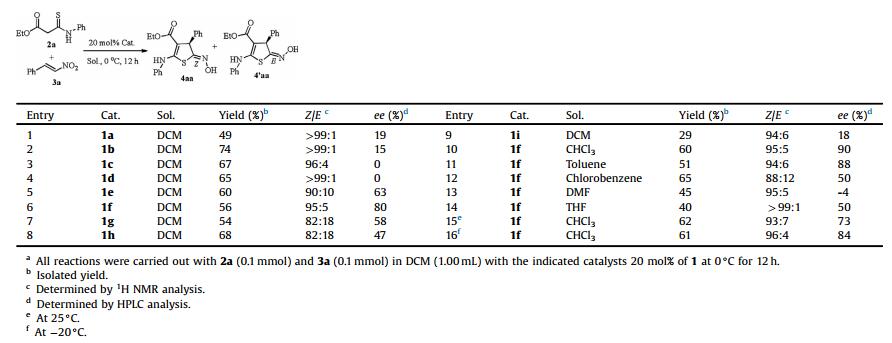

Table 1 Optimization the reaction conditions.a |

At first, our studies focused on the reaction between the acyclic thioamide 2a and (E)-α-nitrostyrene 3a by using a series of cinchona alkaloids 1a-i as organocatalysts in CH2Cl2 at 0 ℃ (Table 1). We found that the model reaction with 10 mol% quinine 1a proceeded as anticipated furnishing the monocyclic dihydrothiophene 4aa in moderate yield and high Z-selectivity, albeit low enantioselectivity was observed (Table 1, entry 1). Similar results were achieved when the thio[3 + 2] cyclization was catalyzed by cinchonine 1b (entry 2). In hopes of enhancing the enantioinduction, the effects of various bifunctional H-bond donor catalysts 1c-h were then probed under the same conditions (entries 3-8). Cinchona alkaloids 1c-1d bearing a 6'-hydroxyquinoline ring, which have appeared to be efficient organocatalysts for asymmetric additions, were also found to effect the thio[3 + 2] cyclization in high Z-selectivity, however, only a racemic dihydrothiophene 4aa was obtained (entries 3-4). Switching from 1a and 1b to bifunctional thioureas 1e-h led to good stereochemical induction (entries 5-9). Gratifyingly, excellent selectivity and good enantioselectivity were achieved when the thio[3 + 2] cyclization was catalyzed by cinchonine quinine-derived bifunctional thiourea 1f and 1f was identified as the best catalyst among those screened (entry 6). Subsequently, a few commonly used solvents were screened. Aromatic hydrocarbon solvent toluene afforded moderate yield and good enantioselectivity (entry 11), on the contrary, when the reaction was carried out in chlorinated aromatic solvent chlorobenzene, product 4aa was isolated in similar yield, while the enantioselectivity was decreased (entry 12). After a brief survey of solvents revealed that CHCl3 was better than other solvents tested and the dihydrothiophene 4aa was isolated in moderate yield with excellent Z-selectivity and enantioselectivity (entry 10). Lowering the reaction temperature to -20 ℃ led to a slight decrease of enantioselectivity, as well as increasing the reaction temperature to 25℃ (entries 15, 16). Based on the above screening, the optimal reaction conditions: 1.0 equiv. 1a and 1.0 equiv. 2a in CHCl3 with 20 mol% catalyst 1f at 0 ℃ were established.

|

|

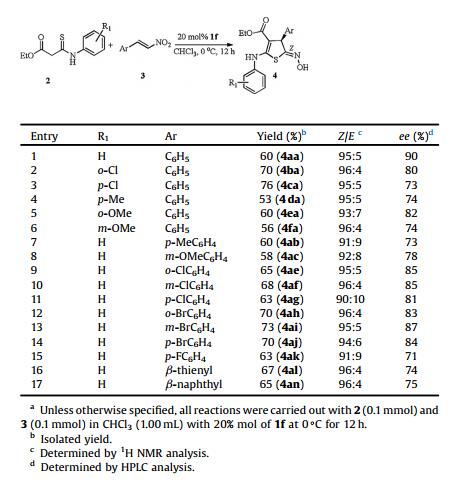

Table 2 Asymmetric Domino Michael/cyclization of thioamides 2 to (E)-a-nitrostyrenes 3.a |

With the optimized reaction conditions at hand, we applied the optimized reaction conditions to investigate the generality for the scope of the acyclic thioamides 2 and (E)-α-nitrostyrenes 3. As shown in Table 2, this new asymmetric catalytic thio[3 + 2] cyclization provides a facile access to a range of full substituted dihydrothiophenes, which contain several functional groups, such as amine, ester and oxime groups, in good enantiomeric excesses and high Z-selectivities. The electronic nature of a substituent on the aromatic moiety of thioamides 2 has little effects on efficiency and regioselectivity of the thio[3 + 2]cyclization with this new methodology (entries 3-4), but the position of the substituent on the phenyl ring have an influence on the enantioselectivities (entries 2-6). A ortho substituent on the aromatic moiety of thioamides 2 afforded higher stereoselectivity than para or meta substituent on the aromatic moiety of thioamides 2 (entries 2, 5 vs. entries 3, 4, 6). Further exploration of the substrate scope was focused on (E)-α-nitrostyrenes 3 bearing neutral, electron-donating, electron-withdrawing groups at the phenyl ring (entries 7-15). The results showed that the electronic nature of substituents on the aryl ring of (E)-α-nitrostyrenes, including Me, OMe, Cl, and Br groups, has an impact on enantioselectivity of the thio[3 + 2] cyclization. Obviously, the electronically deficient (E)-α-nitrostyrenes afforded higher stereoselectivity than the electronically rich derivatives (entries 9-14 vs. 7-8). But the strong electronically deficient (E)-α-nitrostyrene 3k afford multi-functionalized dihydrothiophenes with slightly inferior enantioselectivity (entry 15). In addition, (E)-α-nitrostyrene 3l bearing a heteroaromatic ring was also viable substrate for the 1f-catalyzed enantioselective the thio[3 + 2]cyclization (entry 16). Increasing steric hindrance of 3, satisfactory yields as well as excellent Z-selectivity and good enantioselectivity were observed (entry 17). The absolute configuration of the polyfunctionalized spiroannulated dihydrothiophenes confirmed by single-crystal X-ray analysis of representative enantiopure 4aa that bears a sulfur atom. As shown in Fig. 3, it composes of (C1Z, C2R) configuration (Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 30% probability level. | |

In summary, we have successfully demonstrated the organocatalytic asymmetric a formal thio[3 + 2]cyclization of acyclic thioamides with (E)-α-nitrostyrenes provides a facile synthetic route to optically active monocyclic dihydrothiophenes with excellent regio-, chemo-and enantioselectivities, by employing bifunctional thiourea 1f as the organocatalyst and using an umpolung strategy as a key step. These novel full substituted dihydrothiophenes, which contain several functional groups, such as amine, ester and oxime groups, could serve as chiral building blocks useful for access to a large variety of target molecules possessing biological/pharmacological activity.

AcknowledgmentFinancial support for this work provided by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21272214) is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2017.08.048.

| [1] |

(a) E. Campaigne, Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry, Pergamon, Oxford U. K., 1984, pp. 863-934; (b) S. Gronowitz, A. B. Hornfeldt, Thiophenes, Elsevier, Oxford U. K., 2004; (c) G. C. Nandi, S. Samai, M. S. Singh, J. Org. Chem. 76(2011) 8009-8014; (d) W. You, X. Yan, Q. Liao, C. Xi, Org. Lett. 12(2010) 3930-3933. |

| [2] |

P.S. Wei, M.X. Wang, D.C. Xu, J.W. Xie, J. Org. Chem. 81 (2016) 1216-1222. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.5b02369 |

| [3] |

V.A. Tsygankova, Y.B. Blume, Biopolim. Kletka 13 (1997) 484-492. |

| [4] |

(a) G. Hallas, A. D. Towns, Dyes Pigments 33(1997) 319-336; (b) M. K. R. Fischer, S. Wenger, M. Wang, et al., Chem. Mater 22(2010) 1836-1845. |

| [5] |

(a) C. B. Nielsen, J. M. Fraser, B. C. Schroeder, et al., Org. Lett. 13(2011) 2414-2417; (b) J. Wang, K. Liu, Y. Y. Liu, et al., Org. Lett. 11(2009) 2563-2566; (c) C. Qiao, K. Q. Ling, E. M. Shepard, D. M. Dooley, L. M. Sayre, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128(2006) 6206-6219. |

| [6] |

(a) J. Zempleni, S. S. K. Wijeratne, Y. I. Hassan, Bio. Factors 35(2009) 36-46; (b) S. Benetti, C. D. Risi, G. P. Pollini, V. Zanirato, Chem. Rev. 112(2012) 2129-2163; (c) K. Haraguchi, H. Shimada, H. Tanaka, et al., J. Med Chem. 51(2008) 1885-1893. |

| [7] |

E. Hauptman, R. Shapiro, W. Marshall, Organometallics 17 (1998) 4976-4982. DOI:10.1021/om980540t |

| [8] |

(a) E. M. McGarrigle, E. L. Myers, O. Illa, et al., Chem. Rev. 107(2007) 5841-5883; (b) N. Furukawa, Y. Sugihara, H. Fujihara, J. Org. Chem. 54(1989) 4222-4224; (c) A. H. Li, L. X. Dai, X. L. Hou, Y. Z. Huang, F. W. Li, J. Org. Chem. 61(1996) 489-493; (d) K. Julienne, P. Metzner, J. Org. Chem. 63(1998) 4532-4534; (e) J. Zanardi, C. Leriverend, D. Aubert, K. Julienne, P. Metzner, J. Org. Chem. 66(2001) 5620-5623; (f) J. Zanardi, D. Lamazure, S. Miniere, V. Reboul, P. Metzner, J. Org. Chem. 67(2002) 9083-9086; (g) M. T. Huang, H. Y. Wu, R. J. Chein, Chem. Commun. 50(2014) 1101-1103. |

| [9] |

(a) L. P. Garrod, Br. Med. J. 1(1960) 527-529; (b) C. J. Schofield, J. E. Baldwin, M. F. Byford, et al., Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7(1997) 857-864; (c) K. C. Nicolaou, D. Vourloumis, N. Winssinger, P. Baran, Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 39(2000) 44-122. |

| [10] |

(a) M. Yoshikawa, T. Murakami, H. Shimada, et al., Tetrahedron Lett. 38(1997) 8367-8370; (b) M. Yoshikawa, T. Murakami, K. Yashiro, H. Matsuda, Chem. Pharm. Bull. 46(1998) 1339-1340; (c) H. Matsuda, T. Murakami, K. Yashiro, J. Yamahara, M. Yoshikawa, Chem. Pharm. Bull. 47(1999) 1725-1729. |

| [11] |

(a) J. Zempleni, S. S. K. Wijeratne, Y. I. Hassan, Bio. Factors 35(2009) 36-46; (b) S. Benetti, C. D. Risi, G. P. Pollini, V. Zanirato, Chem. Rev. 112(2012) 2129-2163. |

| [12] |

(a) S. Benetti, C. D. Risi, G. P. Pollini, V. Zanirato, Chem. Rev. 112(2012) 2129-2163; (b) A. M. Ponce, L. E. Overman, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122(2000) 8672-8676; (c) D. Desmaele, S. Delarue-Cochin, C. Cave, J. Angelo, G. Morgant, Org. Lett. 6(2004) 2421-2424; (d) S. Brandau, E. Maerten, K. A. Jørgensen, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128(2006) 14986-14991; (e) H. Li, L. Zu, H. Xie, J. Wang, W. Wang, Org. Lett. 9(2007) 1833-1835; (f) C. Yu, Y. Zhang, A. Song, Y. Ji, W. Wang, Chem. Eur. J. 17(2011) 770-774; (g) J. Tang, D. Q. Xu, A. B. Xia, et al., Adv. Synth. Catal. 352(2010) 2121-2126. |

| [13] |

(a) X. M. Zeng, C. Y. Meng, J. X. Bao, et al., J. Org Chem. 80(2015) 11521-11528; (b) X. M. Zeng, J. W. Xie, J. Org. Chem. 81(2016) 3553-3559. |

| [14] |

(a) J. W. Xie, M. L. Xu, R. Z. Zhang, J. Y. Pan, W. D. Zhu, Adv. Synth. Catal. 356(2014) 395-400; (b) R. Z. Zhang, C. Y. Meng, J. W. Xie, M. L. Xu, W. D. Zhu, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 15(2014) 3104-3107; (c) Y. R. Zhang, J. W. Xie, X. J. Huang, W. D. Zhu, Org. Biomol. Chem. 10(2012) 6554-6561; (d) L. P. Fan, P. Li, X. S. Li, et al., J. Org Chem. 75(2010) 8716-8719. |

2018, Vol. 29

2018, Vol. 29