b Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources Collection and Preservation, Ministry of Agriculture, Institute of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100081, China

Since 1800 s the settlers in the America's western frontier noticed that their livestock displayed a neurologically toxic symptom (locoism) including staggering, and staring vacantly, and then the afflicted animals eventually die after consumption of the notorious "locoweed plants" including Swainsona, Astragalus, and Oxytropis species. Now it was revealed that the agent behind locoism is the toxic alkaloid swainsonine (1S, 2R, 8R, 8aR-1, 2, 8-trihydroxyoctahydroindolizine) (1) [1, 2]. Swainsonine is also produced in different fungi such as Rhizoctonia leguminicola, Metarhizium anisopliae, and recently it has been isolated from endophytic fungus Undifilum oxytropis [3-6]. The producer of swainsonine (1) from locoweed plant Oxytropis was now confirmed completely originated from its endophytic fungus Undifilum oxytropis [3-6], yet it could not conclude that this toxic alkaloid is a fungal secondary metabolite only, because there is still not other evidence to support that swainsonine isolated from locoweed plants are all originated from their endophytic fungi [7-9].

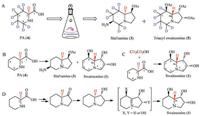

This toxic polyhydroxyoctahydroindolizine alkaloid (1) was first isolated from fungus R. leguminicola by Guengerich and coworkers in 1973, but its structure was elucidated wrongly as a pyridine (2) not an indolizine skeleton [10] (Fig. 1). Colegate in 1979 purified a poly-hydroxyl alkaloid named swainsonine (1) from the toxic plant S. canescens based on bioactivity-guided isolation process, and its structure was characterized by NMR experiment and chemical reactions. In addition, its relative configuration was determined by analysis of its coupling constants [11]. In 1980, based on the result of diacyl swainsonine X-ray diffraction, Skelton further confirmed its planar structure and relative configuration [12]. Several years later, Schneider et al. rectified the wrong structure (2), and characterized structure of swainsonine (1) as what it is (Fig. 1). In addition, its absolute configuration was determined by Horeau's method [13]. Later different groups totally synthesized the structure of swainsonine (1) and now more than 40 synthetic approaches have been reported [14, 15], which implied that this toxic alkaloid was one of the most important star-molecules in the synthetic organic field.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Structural elucidation of swainsonine (1). | |

The potential targets of swainsonine (1)was now revealed to be the mannosidase and Golgi mannosidase Ⅱ [16-18], and this compound could lead to oligosaccharide accumulation in lysosome, and cause the improper glycoprotein synthesis, cellular vacuolation and cellular death of herbivores, whereas a great amount of evidence confirmed that swainsonine (1) possessed diverse biological activities including immunosuppressive effects [19, 20], and anti-virus [21]. Most importantly, swainsonine (1) could suppress the different cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo, and was under consideration as a component of chemotherapeutic treatments for different cancers [22-26]. Though swainsonine (1) has therapeutic potentials as a drug-like lead, the low yield in plants, fungi, or from total synthesis as the bottleneck restricts its further investigation on structure-activity relationship (SAR). This review highlighted the advance of swainsonine biosynthesis from 1973 to 2017 in order to provide insights to solve the bottleneck of this bioactive polyhydroxyoctahydroindolizine alkaloid (1).

2. The biosynthesis of indolizine skeleton in swainsonine (1)Both slaframine (3) and swainsonine (1), isolated from the fungus R. leguminicola, possess the same indolizine skeleton, so Guengerich considered that the pyridine ring in the structure 1 and 3 was originated from the same L-pipecolic acid (4, PA) [27]. Unusually and interestingly, the configuration of C-8a in 1 is different from those of C-8a in 3 and C-2 in 4, respectively.

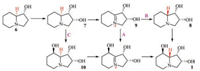

To elucidate the hypothetic biosynthetic pathway, the pipecolic acid-d9 hydrochloride was fed into the culture of R. leguminicola [28]. Swainsonine (1) was isolated from the extract and acetylated to be 1, 2, 8-triacyl swainsonine (5). Mass and 2H NMR analysis confirmed that seven deuterium (D) atoms were incorporated into the structures of 1, 2, 8-triacyl swainsonine (5), implying that two deuterium atoms were lost in the biosynthesis of swainsonine (1). The first deuterium atom was lost at C-8 in 5 by an oxidative reaction (8-CH2-oxidized to be 8-CHOH-), but where was the second D atom lost? Because structure 1 had different absolute configuration at C-8a from that of structure 3, it was guessed that the second D atom at C-8a might be lost in 1. Though it was easy to prove this guess by analysis of 1H NMR and 2H NMR spectra of deuteriumed and non-deuteriumed compound (5), the chemical shift values of H-8a and 7-CH2 were overlapped in the 1H NMR spectrum, which could not differentiate these protons (H-8a and 7-CH2) (Scheme 1, route A). Then Schneider and co-authors did another isotope-labelled experiment: putting [2-2H] pipecolate into the culture to find that the C-8a in 1 did not contained the corresponding 2H atom. This result confirmed that the hydrogen atom at C-8a in 1 did not originate from the proton of C-2 in PA (4) (Scheme 1, route B). Furthermore, Schneider put PA and [1, 2-2H2] ethanol into the culture, and obtained 1 with D-atom at C-8a, again supporting that the proton at C-8a in 1 did not stem from the proton at C-2 of PA (Scheme 1, route C). These confirmed that pipecolic acid was the precursor of swainsonine (1), but the H-8a in 1 did not originate from H-2 of pipecolic acid [28]. From the mentioned above isotope-labelled experiments, it implied that an oxidation reaction might happen with loss of a hydrogen atom and then a reduction reaction incorporated another hydrogen into C-8a in the biosynthetic pathway of 1, which led to the different configuration at C-8a between 1 and 3 (Scheme 1, route D).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Possible biosynthesis of swainsonine (1) from PA constructed by Schneider et al. | |

Harris et al. in 1987 put [3H]-1-hydroxy indolizine (6) into the culture of R. leguminicola, and obtained 1, 2-dihydroxyindolizine (7) besides the isotope-labeled swainsonine (1) and slaframine (3). Then the authors fed [3H]-1, 2-dihydroxy indolizine (7) into R. leguminicola culture and isolated the isotope-labeled swainsonine (1), thus Harris et al. considered that (7) should be the biogenetic precursor of (1), and suggested three possible biosynthetic pathways of swainsonine (1) from 6 and 7 (Scheme 2) [29].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Three possibly biosynthetic pathways from 6 and 7 to 1. | |

In 1988, Harris et al. investigated the chemical constituents of locoweed Astragalus oxyphysus and isolated compounds 6 and 7 besides swainsonine (1). The authors then fed isotope-labeled [3H]-pipecolic acid (4) into A. oxyphysus and found that the pyridine ring in structures of 1, 6 and 7 all possessed the isotopelabelled [3H], implying that PA (4) was the precursor of compounds 1, 6 and 7. Thus Harris et al. thought that swainsonine (1) had the same biogenetic origin in locoweed plant A. oxyphysus and fungus R. leguminicola [30].

Later Harris et al. fed isotope-labelled 7 into R. leguminicola culture, and purified 1 but not 8 and 10. Then the authors considered that pathways B and C in Scheme 2 were not correct. In order to confirm the biosynthetic pathway A, the authors put isotope-labeled 9 into the culture, and expected to obtain 1, but compound 9 was not stable, and was easy transformed into other side products. Though the experiment to test the pathway A was not successful, the investigators considered that pathway A was more reliable than those of pathways B and C [31].

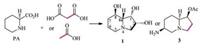

The isotope-labelled experiments confirmed that the pyridine ring including the C-1 in the structure of swainsonine (1) is biosynthesized from pipecolic acid (4), but where does the C-2 and C-3 in swainsonine (1) originate from? In fact, Clevenstine et al. in 1979 did the following experiment: putting [1-14C]-, [2-14C] malonic acid, and [1-14C]-, [2-2H] acetic acid into R. leguminicola and obtained C-2/C-3 isotope-labelled swainsonine (1) and slaframine (3), which confirmed that the C-2 and C-3 in swainsonine (1) were a polyketide origin (Scheme 3) [32].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. The biosynthetic origin of C-2 and C-3 in 1. | |

|

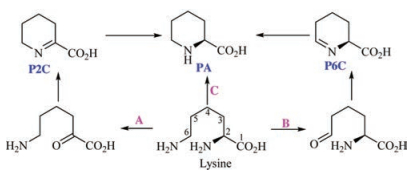

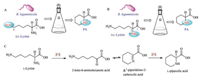

The pipecolic acid is the vital precursor in the biosynthesis of swainsonine (1). A great wealth of evidence implied that pipecolic acid was biosynthesized from lysine, whereas there at least are three biosynthetic pathways from lysine to pipecolic acid in different organisms (Scheme 4) [33]. The first one is the Δ1-piperideine-2-carboxylic acid (P2C) pathway, in which the α-amino group in lysine is oxidized to be the corresponding ketone unit, and then this group automatically reacts with 6-NH2 to form P2C. Finally, the P2C is reduced to be the pipecolic acid (A pathway) [34, 35]. The second one is the Δ1-piperideine-6-carboxylic acid (P6C) pathway. A L-lysine ε-aminotransferase (LAT) catalyzes lysine to form P6C, which then shape PA under the action of pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C) reductase (B pathway) [36-40]. The third pathway arose from the studies of the biosynthesis of rapamycin, FK506 and FK520 [41, 42]. The labelled experiments confirmed that ε-15N not α-15N atom in D, L-lysine was incorporated in the pipecolic acid [43]. Later an enzyme named RapL was suggested to catalyze the deaminative cyclization from L-lysine to L-pipecolic acid [44-47]. So which pathway is the corresponding one from lysine to pipecolic acid in the biosynthesis of swainsonine (1)?

Guengerich and Broquist in 1973 put [15N6]-lysine and [15N2]-lysine into R. leguminicola and obtained [15N6]-pipecolic acid. Then the authors viewed that the 2-amino group in [15N6]-lysine was oxidized to be the corresponding [15N6]-2-keto-6-aminohexanoic acid

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 5. The biosynthesis from lysine to PA in R. leguminicola suggested by Guengerich. | |

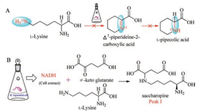

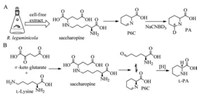

To test validity of the experimental results suggested by Guengerich, Wickwire and Broquist in 1990 reinvestigated the biosynthesis of PA from lysine. The Δ1-piperideine-2-carboxylic acid was not isolated according to the experimental methods Guengerich ever used (Scheme 6, pathway A), but when the investigators mixed the crude enzymes from R. leguminicola culture with α-keto glutarate, NADH, and lysine, they purified an unexpected product peak I as saccharopine. The authors then established the biosynthetic pathway from lysine to saccharopine (Scheme 6, pathway B) [49].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 6. The biosynthesis of saccharopine from lysine. | |

Saccharopine was added to the cell free extract of R. leguminicola culture with an additional peak observed in the HPLC analysis, of which the retention time was same as that of Δ1-piperideine-6-carboxylic acid (P6C). Mixing this additional peak with NaNB2H3 shaped the corresponding product [2H6] pipecolic acid, which further confirmed that the additional peak was Δ1-piperideine-6-carboxylic acid (Scheme 7, pathway A), thus the authors reconstructed the biosynthetic pathway from lysine to pipecolic acid in R. leguminicola: first lysine reacted with α-keto glutarate to generate saccharopine, and then oxidation of saccharopine shaped glutamic acid and α-aminoadipic semialdehyde (

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 7. The pipecolic acid biosynthesis in R. leguminicola. | |

4. Functional investigations of genes or gene cluster of swainsonine biosynthesis

The biosynthesis of swainsonine (1) is established by using isotope-labelled approaches according to the mentioned above results, but the potential intermediates in the biogenetic pathway are usually highly hydrophilic or unstable, or do not possess strong chromophores, which makes it very difficult to purify these key compounds. With the great development of microbial deepsequencing techniques, it is very convenient to obtain the whole genome data of a fungus, from which the gene clusters synthesizing secondary metabolites could be elucidated by combination of bioinformatics, genetic and chemical methods. Now different groups have began to investigate the biosynthetic gene clusters especially the key genes to biosynthesize swainsonine (1).

Mukherjee et al. in 2010 first constructed the genetic transformed system of the locoweed endophytic fungus U. oxytropis, and knocked out the saccharopine reductase gene to found that the output of swainsonine, pipecolic acid and Δ1-piperideine-6-carboxylic acid in the culture increased, whereas the yields of lysine and saccharopine were reduced. This result implied that saccharopine reductase plays a very important role in the biosynthesis of swainsonine (1) [51, 52].

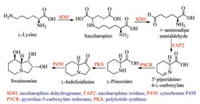

Based on the bioinformatic analysis results of the whole genome data of the endophytic fungus U. oxytropis together with consideration of the mentioned above results suggested by isotope-labelled experiments, Lu in 2016 suggested the possible genes to form swainsonine (1), which includes saccharopine dehydrogenase (SDH) gene, saccharopine oxidase (FAP2) gene, pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase (P5CR) gene, polyketide synthase (PKS) gene and cytochrome P450 gene (Scheme 8) [53]. Though the authors did not provide the corresponding gene cluster of SW, and also did not validate the functions of each gene in the biosynthetic pathway, for the first time, they sequenced the whole genome of the endophytic fungus U. oxytropis, and suggested the possibly key genes to biosynthesize swainsonine.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 8. The biosynthesis of swainsonine (1) suggested by Lu et al. | |

Because different fungi such as M. robertsii, S. leguminicola, U. oxytropis et al. all could produce swainsonine (1), Cook and coworkers targeted the gene cluster (SWN) of compound 1 by using comparative genomic analysis. The gene cluster SWN includes different genes: swnK (PKS-NRPS multifunctional enzyme gene), swnN (an NmrA-like, NADB Rossmann-fold reductase gene), swnR (an NADB Rossmann-fold reductase gene), swnH1 (2-oxoglutaratedependent dioxidase gene), swnH2 (Fe(Ⅱ)-dependat dioxidase gene), swnA (Amino transferase gene), swnT (Transmembrane choline transporter gene), in which the multifunctional enzyme gene swnK included adenylylation gene (A), acyltranserase gene (AT), thiolation gene (T), β-ketoacyl synthase gene (KS), β-ketoacyl reductase gene (KR), reductase (SDR) and thioester reductase gene (SDRe1). The authors inactivated the key gene swnK in M. robertsii, and the transformant could not produce 1, whereas swnK-complemented strain could, in return, produce the alkaloid (1), which confirmed that swnK plays a vital role in the biosynthesis of swainsonine (1), and supported that the SWN is the gene cluster synthesizing this toxic alkaloid 1. Then the investigators estab-lished the biosynthetic pathway of swainsonine (Scheme 9): first PA (4) was activated by possessing a AMP group under the action of adenylylation enzyme, and then reacted with malonyl-CoA by incorporation of two carbon atoms. The followingly successive reductive reactions catalyzed by SDR and SDRe1 enzymes formed the first key precursor (12), which spontaneously shaped the intermediate (13); Then the reductases SwnH1 or SwnH2 transformed 13 to be 1-hydroxyl octahydroindolizin (6), and the continuous oxidations under the two oxidases SwnR or SwnN made 6 to be the end-product swainsonine (1) (Scheme 9) [54]. Though the authors only postulated the functions of key postmodification genes including swnH1, swnH2, swnR and swnN by bioinformatic approaches, they first reported the SW gene cluster by comparative genomics, knock-out and complementation experiments, which will provide the important basis for further investigation of SW biosynthetic pathway.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 9. The biosynthesis of swainsonine (1) suggested by Cook et al. | |

5. Conclusions

Swainsonine (1) was found to be potential inhibitors of mannosidase and Golgi mannosidase Ⅱ, and later was used as molecular probe to investigate the glycoprotein synthesis. Recently, it was revealed that swainsonine (1) displayed a wide range of biological effects especially the anti-cancer cell lines activities. Whereas due to the bottleneck that the low yield of swainsonine (1) was in plants or fungi, and no economically total synthesis route was developed, this restricted the structureactivities relationships (SAR) investigation of this drug-like lead. Biosynthetic pathway elucidation of secondary metabolites will help to analyse and find the key precursors, intermediates, ratelimiting enzymes (genes), transcription regulators and especially the vital post-modification enzymes (genes), which will provide a solid base for increasing the output of swainsonine (1) or provide some thoughts to biomimetically synthesize this compound with economical and efficient approaches. This review highlighted the biosynthetic advance of swainsonine (1) from 1973 to 2017. The biosynthetic pathway framework was set up by using isotopelabelled experiments, but some important intermediates (with highly hydrophily or no chromophores) were still not found, thus new techniques or methods need to be developed urgently. The gene cluster of swainsonine (1) was revealed and confirmed in different fungi including insect pathogen M. robertsii, clover pathogen S. leguminicola, endophytic fungus Undifilum oxytropis, and a fungus belonging to the order Chaetothyriales by compara-tive genome mining and gene-inactivating methods. In fact, the specific functions of key genes including swnA, swnR, swnN, swnH1 and swnH2 in the gene cluster of swainsonine (1) were still not elucidated. The gene of swnT was predicted to be a transmembrane transporter by informatic analysis. If this gene is overexpressed, whether more swainsonine (1) can be transported to be out ofcells, and then SW output will be increased. Cook et al. observed the existence of transcription regulators in the gene cluster of swainsonine (1), and its function is also not tested. Whether overexpression of the transcription regulators could upregulate the mRNA expression in the gene cluster of swainsonine (1), and then increasethe yield of the swainsonine (1)will be an interesting topic. More importantly and interestingly, the change of configuration at C-8a in SW biosynthesis is related to different oxidoreductase reactions, but the specific post-modification genes (swnR or swnN or swnH1 or swnH2) catalysing these reactions are not clear. These are the problems that should be answered in future. In sum up, the biosynthetic advance of swainsonine (1)was highlighted in this review, which expectedly could provide some thoughts for the further biosynthetic investigation or mimetic synthesis of this bioactive alkaloid (1), and then to increase its output in practice.

AcknowledgmentsWe gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31570340, for G. Ding), The National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017ZX09101003-006-006), and the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund for Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (No. 502-17).

| [1] |

X. Huang, J.P. Liang, X.D. Gao, et al., Acta Vet. Zootechnica Sin. 47 (2016) 1075-1085. |

| [2] |

G. D. Yang, Study on Biosynthesis of Swansonine by the Locoweed's Endophytic Fungi, Ph. D Dissertation, Northwest A & F University, 2012.

|

| [3] |

Q.M. Zhao, Y.T. Yu, S.H. He, et al., J. Agric. Sci. 33 (2012) 82-88. |

| [4] |

K. Braun, J. Romeor, C. Liddell, et al., Mycol. Res. 107 (2003) 980-988. DOI:10.1017/S095375620300813X |

| [5] |

D. Cook, D.R. Gardner, J.A. Pfister, J. Agric. Food Chem. 64 (2014) 7326-7334. |

| [6] |

Y.T. Yu, Q.M. Zhao, J.N. Wang, et al., Toxicon 56 (2010) 330-338. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.03.020 |

| [7] |

D. Cook, D.R. Gardner, D. Grum, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 59 (2011) 1281-1287. DOI:10.1021/jf103551t |

| [8] |

D.S. Grum, D. Cook, D. Baucom, et al., J. Nat. Prod. 67 (2013) 1984-1988. |

| [9] |

D. Cook, W.T. Beaulieu, I.W. Mott, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 61 (2013) 3797-3803. DOI:10.1021/jf4008423 |

| [10] |

F.P. Guengerich, S.J. Dimari, H.P. Broquist, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95 (1973) 2055-2056. DOI:10.1021/ja00787a080 |

| [11] |

S.M. Colegate, P.R. Dorlin, C.R. Huxtable, Aust. J. Chem. 32 (1979) 2257-2264. DOI:10.1071/CH9792257 |

| [12] |

B.W. Skelton, A.H. White, Aust. J. Chem. 33 (1980) 435-439. DOI:10.1071/CH9800435 |

| [13] |

M.J. Schneider, F.S. Ungemach, H.P. Broquist, et al., Tetrahedron 39 (1983) 29-32. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)97625-2 |

| [14] |

S.J. Ye, J.L. Liu, W.P. Huang, Chin. J. Org. Chem. 29 (2009) 689-695. |

| [15] |

D.J. Wardrop, S.L. Waidyarachchi, Nat. Prod. Rep. 27 (2010) 1431-1468. DOI:10.1039/b914958a |

| [16] |

D.R.P. Tulsian, T.M. Harris, O. Touster, J. Biol. Chem. 257 (1982) 7936-7939. |

| [17] |

Y.F. Liao, A. Lal, K.W. Moremen, J. Biol. Chem. 271 (1996) 28348-28358. DOI:10.1074/jbc.271.45.28348 |

| [18] |

A. Bastida, A. Fernandez-Mayoralas, R.G. Arrayas, et al., Chem. Eur. J. 7 (2001) 2390-2397. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1521-3765 |

| [19] |

S.L. White, K. Schweitzer, M.J. Humphries, et al., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 150 (1988) 615-625. DOI:10.1016/0006-291X(88)90437-8 |

| [20] |

T. Kino, N. Inamura, K. Nakahara, et al., J. Antibiot. 38 (1985) 936-940. DOI:10.7164/antibiotics.38.936 |

| [21] |

E. Borges de Melo, A. da Silveira Gomes, I. Carvalho, Tetrahedron 62 (2006) 10277-10302. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2006.08.055 |

| [22] |

M.J. Humphries, K. Matsumoto, S.L. White, et al., Cancer Res. 48 (1988) 1410-1415. |

| [23] |

C. Galustian, S. Foulds, Frances Dye J., et al., Immunopharmacolgy 27 (1994) 165-172. DOI:10.1016/0162-3109(94)90051-5 |

| [24] |

H. Lu, J.J. Wang, L.S. Sun, et al., Progr. Vet. Med. 30 (2009) 87-90. |

| [25] |

S.S. Chen, B.Y. Zhao, G. Rui, et al., Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 16 (2004) 66-70. |

| [26] |

A. Myc, J.E. Kunicka, M.R. Melamed, et al., Cancer Res. 49 (1989) 2879-2883. |

| [27] |

F.P. Guengerich, S.J. Dimari, H.P. Broquist, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 95 (1973) 2055-2056. DOI:10.1021/ja00787a080 |

| [28] |

M.J. Schneider, F.S. Ungemach, H.P. Broquist, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104 (1982) 6863-6864. DOI:10.1021/ja00388a102 |

| [29] |

T.M. Harris, C.M. Harris, J.E. Hill, et al., J. Org. Chem. 52 (1987) 3094-3098. DOI:10.1021/jo00390a024 |

| [30] |

C.M. Harris, B.C. Campbell, R.J. Molyneux, et al., Tetrahedron Lett. 29 (1988) 4815-4818. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)80616-4 |

| [31] |

C.M. Harris, M.J. Schneider, F.S. Ungemach, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110 (1988) 940-949. DOI:10.1021/ja00211a039 |

| [32] |

E.C. Clevenstine, H.P. Broquist, T.M. Harris, Biochemistry 18 (1979) 3658-3663. DOI:10.1021/bi00584a003 |

| [33] |

M. He, J. Ind. Microbiol. Biothechnol. 33 (2006) 401-407. DOI:10.1007/s10295-006-0078-3 |

| [34] |

Y.F. Chang, E. Adams, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 45 (1971) 570-577. DOI:10.1016/0006-291X(71)90455-4 |

| [35] |

D.L. Miller, V.W. Rodwell, J. Biol. Chem. 246 (1971) 2758-2764. |

| [36] |

N. Rius, A.L. Demain, J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 7 (1997) 95-100. |

| [37] |

Y. Aharonowitz, G. Cohen, J.F. Martin, Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46 (1992) 461-495. DOI:10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.002333 |

| [38] |

M.B. Tobin, S. Kovacevic, K. Madduri, et al., J. Bacteriol. 173 (1991) 6223-6229. DOI:10.1128/jb.173.19.6223-6229.1991 |

| [39] |

T. Fujii, T. Narita, H. Agematu, et al., J. Biochem. 128 (2000) 391-397. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022766 |

| [40] |

K. Soda, H. Misono, T. Yamamoto, Biochemistry 7 (1968) 4102-4109. DOI:10.1021/bi00851a045 |

| [41] |

M.E. Cardenas, D. Zhu, J. Heitman, Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 4 (1995) 472-477. DOI:10.1097/00041552-199511000-00002 |

| [42] |

J. J. G. B. Sanglier, M. Dreyfuss, T. Fehr, et al., Immunosuppressants of Microbial Origin, Developments in Industrial Microbiology Series, vol. 32, Wm, C. Brown Publisher, Dubuque, 1993, pp. 1-27.

|

| [43] |

K.M. Byrne, A. Shafiee, J. Nielsen, et al., Dev. Ind. Microbiol. 32 (1993) 29-45. |

| [44] |

I. Molnar, J.F. Aparicio, S.F. Haydock, et al., Gene 169 (1996) 1-7. DOI:10.1016/0378-1119(95)00799-7 |

| [45] |

T. Schwecke, J.F. Aparicio, I. Molnar, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92 (1995) 7893-7843. |

| [46] |

N. Sans, U. Schindler, J. Schroder, Eur. J. Biochem. 173 (1988) 123-130. DOI:10.1111/ejb.1988.173.issue-1 |

| [47] |

U. Schindler, N. Sans, J. Schroder, J. Bacteriol. 171 (1989) 847-854. DOI:10.1128/jb.171.2.847-854.1989 |

| [48] |

F.P. Guengerich, H.P. Broquist, Biochemistry 12 (1973) 4270-4274. DOI:10.1021/bi00745a035 |

| [49] |

B.M. Wickwire, C.M. Harris, T.M. Harris, et al., J. Biol. Chem. 265 (1990) 14742-14747. |

| [50] |

B.M. Wickwire, C. Wagner, H.P. Broquist, J. Biol. Chem. 265 (1990) 14748-14753. |

| [51] |

S. Mukherjee, A.L. Dawe, R. Creamer, J. Microbiol. Method 81 (2010) 160-165. DOI:10.1016/j.mimet.2010.02.015 |

| [52] |

S. Mukherjee, A.L. Dawe, R. Creamer, Fungal Biol. 116 (2012) 902-909. DOI:10.1016/j.funbio.2012.05.007 |

| [53] |

H. Lu, H. Y. Quan, Z. H. Ren, et al., Sci. Rep. 6(2016) 30760.

|

| [54] |

D. Cook, B.G.G. Donzelli, R. Creamer, et al., G3:Genes|Genomes|Genetics 7 (2017) 1791-1797. |

2018, Vol. 29

2018, Vol. 29