b Key Laboratory of Special Function Materials and Structure Design, Ministry of Education, Lanzhou 730000, China;

c Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences, CAS Key Laboratory of Molecular Recognition and Function, CAS Research/Education Center for Excellence in Molecular Sciences, Institute of Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China;

d University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Rhenium (abbreviated as Re) was discovered by Noddack and Berg in 1925, which was the last natural element discovered [1]. It was named after the Rhine River of its discoverers' motherland. Currently, the worldwide fast uprising demand for rhenium is attributed to its irreplaceable applications in nuclear, aerospace, missile, petrochemical fields, among others. In recent years, two main uses of rhenium in China are in the petro-chemistry (as petroleum refinement catalyst) and aviation/space technologies (as heat resistant materials). According to the reports and estimation, rhenium will be a strategic resource for China in the future [2, 3].

Rhenium is a silvery-white metal, located in the position of row 4 and group 7 of the periodic table. With an estimated average content of 1 ppb in the earth's crust (10-9), rhenium is one of the rarest elements [4]. Meanwhile, rhenium has the third-highest melting point (3459 K) and the second-highest boiling point (5869 K) of all elements. This makes rhenium a unique metal for the production of combustion chambers, turbine blades, and exhaust nozzles of jet engines as composition of nickel-based super-alloy, which contains up to 6% rhenium.

Rhenium shares the same group with manganese and technetium, and thus has a lot of chemical properties in common with them. Because rhenium shows a wide range of oxidation states (ranging from -1 to +7) in its compounds, the variability of valences makes rhenium suitable for the production of petroleum refinement catalysts [5-11]. Another important use of rhenium is as a catalyst (Pt-Re catalyst) for the reforming of naphtha in gasoline (Rheniforming process). Because of the low availability of rhenium, related to high demand, rhenium is expensive, with an average price of 2600 US$ per kilogram (until 2016, catalytic-grade NH4ReO4) and increasing annually [12].

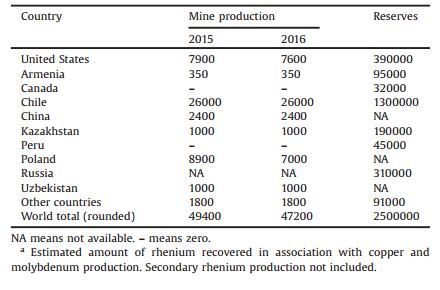

1.2. OccurrenceAs mentioned above, rhenium is the 77th abundant element, one of the rarest, in earth's crust. Rhenium is usually found with other main minerals as molybdenum-copper porphyry deposits with contents up to 0.2%. While the only documented occurrence of rhenium as a mineral, rheniite (ReS2), was found only near the Russian Kudryavyi volcano, Iturup Island, in the Kuril Islands [13]. Kudryavi produced up to 20–60 kg rhenium per year mostly in the form of rhenium disulfide (ReS2), which cannot meet the large demands all around the world. Currently, the major commercial source of rhenium is from the extraction and refinement of molybdenum and copper ores as a by-product. Chile has the world's largest rhenium mineral reserves (about 1.3 million kg associated with the copper ore) and produced the most rhenium (about 26, 000 kg in 2016). United States, Poland and Kazakhstan produced 7600, 7000 and 1000 kg rhenium in 2016, respectively [12]. As for China, it has produced 2400 kg rhenium in 2016 and Jiangxi Copper Corporation was the biggest producer in China, which controlled more than 40% of the Chinese market [14]. The world mine production and reserves are shown below (Table 1) [12].

|

|

Table 1 World mine production and reserves.a |

Nearly 90% reserves of rhenium (estimated up to 237, 000 kg) in China were associated with molybdenum, i.e., molybdenite (MoS2), which was found in Jincheng (Shaanxi province), Luanchuan (Henan province), Daheishan (Jilin province) and Duobaoshan (Heilongjiang province) [15].

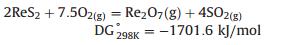

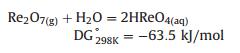

1.3. Separation and enrichmentNow, the practicable ores containing rhenium in industry are copper concentrates and molybdenite (MoS2). Typically, rhenium exists in mixed copper/molybdenum deposits, which is firstly separated from the copper (accompanied with molybdenum), using conventional concentration technologies such as froth flotation. After the primary separation, molybdenum trioxide (MoO3) is produced via pyrometallurgical roasting or hydrometallurgical pressure oxidation processes. Thus the molybdenum trioxide (MoO3), a basic raw material for most commercially used products of molybdenum, is recovered with small amount of rhenium (estimated up to 0.2%). In pyrometallurgical roasting process of molybdenum concentrates, rhenium is oxidized to rhenium heptoxide (Re2O7) via the following simplified reaction (Eq. (1)). Thanks to the fact that rhenium heptoxide is extremely volatile (Pvap = 711 mmHg at 633 K), the temperatures used for molybdenum roasting (about 900–950 K) ensure that nearly all of the rhenium present is volatilized. Next, rhenium is extracted from water where molybdenum roaster-flue gas is absorbed (Eq. (2)). Finally, the perrhenic acid (HReO4) or aqueous rhenium is recovered through solvent extraction or ion-exchange processes giving the end precursor product as ammonium perrhenate (NH4ReO4) via recrystallization [16].

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

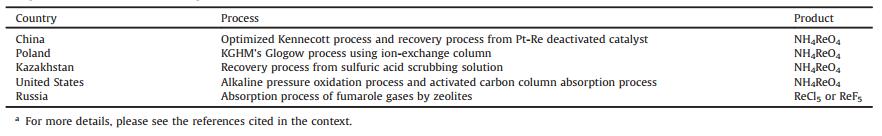

In general, the dominant processing all over the world for rhenium recovery is related to various acid solutions, which are formed during the aqueous purification of dust-gas mixture. Such mixture is usually produced from the pyrometallurgical processing of molybdenite and/or copper concentrates. The main production countries using this process include Chile, USA, Russia and China [12]. A brief comparison of worldwide rhenium processes is shown below (Table 2).

|

|

Table 2 Comparison of worldwide industrial processes.a |

1.4. Unsolved problems

The apparent trend of growing consumption of rhenium not only increases its price but also enlarges the gap between supply and demand. To solve this problem, rhenium may be recovered either from raw materials (solutions from processing of copper and copper-molybdenum concentrates) with improved separation/ enrichment technologies, or from recycled materials containing rhenium (such as dust, slime, spent catalysts, waste recycling alloys, etc.). The key to the question is how to increase the yield and purity of rhenium products and decrease the cost as much as possible. As for China, in light of the fact that most rhenium is associated with molybdenum and/or copper, the challenge is to explore advanced methods to separate rhenium from molybdenum and concentrate it both in laboratories and manufactories in a more effective and economical way. Also, the technologies, which are related with recycling rhenium from spent Pt-Re catalysts or other secondary resources, need to be studied.

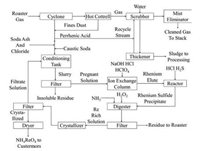

2. Industrial processes 2.1. ChinaThe Kennecott Process is a conventional processing in industry for more than 40 years worldwide. During this process, exhaust gases from the molybdenum roasting circuit are washed with water to produce perrhenic acid in the end [17]. The mother liquor is circulated continuously through the scrubber circuit until the rhenium concentration reaches at least of 100 mg/L. Then, the solution is conditioned with NaOH, soda ash and oxidized with Ca (ClO)2 for 24 h. In order to precipitate any contaminants (primarily iron) remaining in the solution and filtrate them out, the pH of this solution should be adjusted to 10. After the filtration, the solution is sent to an ion exchange processing, where the resin adsorbs the aqueous rhenium from the alkaline solution, and then the rhenium is stripped by the addition of hydrochloric acid. For the sake of removing adsorbed molybdenum on the resin, a caustic soda solution is used, and molybdenum can be recovered as calcium molybdate (CaMoO4) subsequently. When perchloric acid (HClO4) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) are added to the stripping solution, rhenium is precipitated as rhenium sulfide (Re2S7). This precipitate is dissolved in a solution of ammonia and hydrogen peroxide, from which it crystallizes as ammonium perrhenate (NH4ReO4) and further purification steps can be undertaken by recrystallization as well. The whole flowsheet for the Kennecott process is illustrated herein (Fig. 1).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. The original Kennecott process. | |

Industrial practice in China involves the recovery of rhenium as by-product after molybdenite concentrate flotation. Thus the final content of MoS2 may come up to 85%–95%, while the rhenium content, typically, in MoS2 ranges from 0.02% to 0.2% [18]. Since the metallurgical and catalytic applications of molybdic oxide (MoO3) are the primary needs, preparing metallurgical and chemical grade molybdic oxide will release rhenium from the MoS2 lattice during pyrometallurgical processing at the same time. In China, oxidizing roasting is the principal method in industry to produce MoO3 from MoS2. This method also releases rhenium from MoS2 as gaseous Re2O7 species, which is captured from the roaster off gases by a scrubbing processing afterwards.

Many producers in China are applying the traditional Kennecott process excepting for Jiangxi Copper Corporation [15, 19, 20]. It was the biggest rhenium producer in China in 2016 (> 2000 kg per year) and took up more than 40% share of Chinese market. It developed and applied its own production processing including solvent extraction of scrubbing liquid, stripping of the organic solvent, purification and crystallization of NH4ReO4, with the final yield of rhenium up to 92%. The key parameters to the recovery processes were the utilization of the mixture extractive solvent of N335 (20%), 2-octanol (15%), kerosene (65%), while keeping the contact time to about 1 min. In addition, aqueous ammonia (> 7 mol/L) was used as stripping liquid and the rhenium could be concentrated (2g/L) accordingly [18].

Meanwhile, China is the largest platinum group metals (PGMs) consuming country in the world and the mineral resources of PGMs are very rare worldwide [21]. Therefore, the recovery of PGMs from secondary resources is very important not only in China but also in other countries. On one hand, the petroleum reforming catalysts, containing Re and Pt and alumina substrate, are widely used in the refining industry to improve the octane level of fuels [16]. There are two basic methods for the recovery of rhenium and other PGM metals when these catalysts were deactivated:

(1) Complete dissolution of the alumina substrate;

(2) Selective dissolution and recovery of rhenium and platinum.

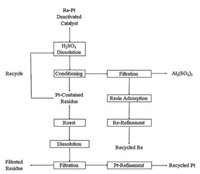

On the other hand, Sino-Platinum Metals (Yimen) Co., Ltd. applied a selective dissolution and recovery processing of Pt-Re deactivated catalyst [22], this processing was modified from the prototype developed by Kumming Institute of Precious Metals since 1970s [23, 24]. The processing was composed of selective dissolution (H2SO4), filtration, and ion exchange resin absorption of rhenium. The filtrated residues were calcined and gaseous rhenium was absorbed by ammonia and treated by ion exchange resins. Thus, the total recovery yield of Re was up to 95%. The whole process is shown below (Fig. 2).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. The optimized process used in Sino-Platinum Metals Co., Ltd. | |

2.2. Other countries

The major producers of the rhenium metal and compounds worldwide were Chile, Poland, Kazakhstan, and the United States (in 2016). The Molymet Corporation (Nos, Chile) operated the largest rhenium recovery plant in the world with an estimated capacity of 40, 000 kg per year of the rhenium metal and NH4ReO4. In addition, Molymet has molybdenum concentrate roasting facilities in Mexico (Molymex S.A. de C.V.), roasting and ferromolybdenum plants in Belgium (Sadaci n.V.), a powder metallurgy plant in Germany (Chemiemetall Gmbh), and a metal facility in China (Luoyang high-tech molybdenum & Tungsten material Co., Ltd.) [25].

Mass production of rhenium from Poland's own sources was launched in 2007 [4]. This production was mainly developed by scientists from the Institute of Non Ferrous Metals in Gliwice, Poland. The KGHM Polska Miedź S.A. Company used acid industrial effluent, which came from cooper ores extraction processing, and obtained crystalline NH4ReO4 in the first step, which was then sintered in the form of pellets and reduced to metallic rhenium subsequently.

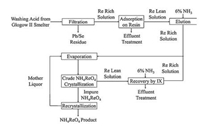

Notably, KGHM's Glogow smelting facility utilized ion exchange technology for the recovery of aqueous rhenium from copper concentrate smelter flue gas [26]. Similar to the Kennecott process, the Re2O7 (volatilized from copper concentrate) was scrubbed by water, thus the absorption solution (typical rhenium concentration was 0.02 g/L) was obtained with various other impurities, including molybdate, sulfate and sulfate salts. This solution was sent to a closed polypropylene filter to remove any residues before the ion exchange step, the solution was then eluted through a series of ion exchange columns, where perrhenate anion (ReO4-) was selectively adsorbed on the weak basic anionic resin. After the absorption, the rhenium was eluted by ammonia solution. Finally, the ammonia eluent was sent to the vacuum crystallization circuit, where NH4ReO4 was produced. Additionally, several times of recrystallizations were necessary to prepare a high-grade (99.95% pure) ammonium perrhenate product. The Glogow smelter facility has the capability to produce 4000–5000kg of ammonium perrhenate per year. The whole process is shown below (Fig. 3).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. The whole process of KGHM Ecoren rhenium recovery at the Glogow smelter. | |

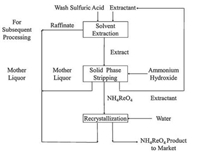

The copper concentrates found in Zhezkazgan (Kazakhstan) contains up to 30 g/t of rhenium, which is the richest rhenium containing deposits in the world [27]. Hence, Abisheva et al. proposed an electrosmelted process for these ores, where the rhenium was volatilized as rhenium heptoxide (Re2O7), and was scrubbed with water and dilute sulfuric acid to form perrhenic acid (HReO4, up to 0.25g/L) [27]. Then the aqueous rhenium solution was sent to a solvent extraction step for selective separation using trialkylamine (TAA) organic compound in a kerosene diluent as the extractant. The loaded organic phase was stripped by ammonium hydroxide giving ammonium perrhenate as the raw product. The organic raffinate was designed to be reused, and the crude rhenium could be dissolved and recrystallized to produce the target ammonium perrhenate (>98.5% purity). A flowsheet of this process is shown in Fig. 4.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Flowsheet for the recovery of rhenium from sulfuric acid scrubbing solution in Kazakhstan. | |

As an alternative to traditional roasting processing, RioTinto (in United States) developed an alkaline pressure oxidation process for the recovery of molybdenum and rhenium from molybdenite concentrates [28]. In this process, the molybdenite concentrate, which was enriched by flotation, was leached with KOH/NaOH at elevated temperature (150–200 ℃) and pressure (517–1400kPa) to form soluble molybdate (MoO42-). The aqueous molybdate was recovered by solvent extraction and stripped with an ammonium hydroxide eluent. The rhenium in the molybdenite concentrate was recovered in the solvent extraction step simultaneously and absorbed by selective ion exchange resin, which contains quaternary amine functional groups.

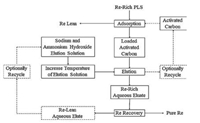

In 2009, Freeport-McMoRan (in United States) applied for a patent for its proprietary method of rhenium recovery. Specifically, rhenium could be obtained as a byproduct from the copper leaching and molybdenum oxidation processing [29]. The core step was an activated carbon column circuit for absorption of the aqueous rhenium. During the desorption processing, rhenium was stripped byan eluent solution at the pH of 7 and the temperature of 80–110 ℃. The eluent contained approximately 2.5% sodium hydroxide and 2.5% ammonium hydroxide. After elution, the rhenium-rich stream was sent to produce a pure rhenium product, and then the rhenium-barren eluting solution would be reused in the circuit if possible. An example of Freeport-McMoRan's suggested rhenium recovery circuit is shown here (Fig. 5).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Freeport pressure oxidation rhenium recovery process. | |

After the discovery of rheniite (ReS2) at Kudryavyi volcano in the mid-1990s, Russian researchers found that the high-temperature fumarole gases from the volcano contained rhenium (0.5– 2.5 g/t) considerably in the form of gaseous rhenium chlorides (ReCl5) and fluorides (ReF5). Presently, researchers are working on applying zeolites as absorption medium for the fumarole gases. They operated this process on a pilot scale in 2007 [30, 31]. Because of the inherent danger of the volcano environment and lack of infrastructure there, the progress was carried on in a quite slow rate.

3. Laboratory trials 3.1. General principleAs stated earlier, rhenium are always found in the ores as a minor component such as copper concentrate or molybdenite (of content < 1%) [1]. This makes rhenium a rare and pricey element for its challenging separation and enrichment requirements. The primary step in industry is to separate and enrich rhenium from the major ore-forming elements, which is well developed and applied in industry, such as pyrometallurgical oxidation of raw ore and following scrubbing of Re(Ⅶ) oxidative gaseous species. The laboratory works in China are mainly focused on the following separation process, which is usually between rhenium and other metal elements in scrubbing solution [16]. For example, the labscale separation between Re(Ⅶ) and Mo(Ⅵ) can be conducted on weak basic anion exchangers by means of sorption-desorption process [32]. The sulphuric and nitric-sulphuric acid solutions used in the separation experiment are obtained from pyrometallurgical and nitric acid processing of rhenium-containing molybdenum concentrates. The chelating differences between Re(Ⅶ) and Mo(Ⅵ) on weak basic anion exchange resin are the foundation for the separation.

Also, other physical and chemical differences can be applied in the rhenium separation and enrichment processing. For instance, solventextraction is based onthe chelation and solubility differences [33]. The extractive resin used in lab separationwas based on the fact that rhenium ions had their unique radii and affinity to the specific resin thus could be differentiated from other ions.

3.2. Ion exchangeMany kinds of ion exchange resins have been widely investigated and used in the area of separation and enrichment for rhenium, owing to the relative convenient operating conditions and low costs of these resins. However, the main challenge for the preparation of resins comes as how to increase the inherent selectivity and stability.

The absorption properties of 4-amino-1, 2, 4-triazole resin (4-ATR) for Re(Ⅶ) were investigated by Xiong et al. in 2007 [34]. The influence of operation parameters such as temperature, pH changes of initial solution, and contact time was studied. The saturated absorption capacity of 4-ATR resin was up to 354 mg/g (298 K in HOAc–NaOAc medium, pH 2.6). The absorption behavior of 4-ATR obeyed the Freundlich empirical equation, and the absorption heat was -11.8 kJ/mol. The fitting molar ratio of 4-ATR (functional group) to Re(Ⅶ) was about 2:1. Re(Ⅶ) absorbed on 4-ATR was eluted by HCl (1.0–5.0 mol/L) and the yield could reach nearly 100% when the elution solution of hydrochloric acid (4.0 mol/L) was utilized.

In 2009, Wu et al. studied the absorption properties of Re(Ⅶ) on D301 resin (D301R), of which the saturated absorption capacity was 715 mg/g (298 K in HOAc-NaOAc medium, pH 2.7) [35]. Besides, the rhenium absorbed on D301R could be eluted by HCl (0.5-5.0 mol/L), and the best desorption operation should be eluted by 4.0 mol/L HCl solution (yield nearly 100%). This absorption obeyed the Freundlich formula and was an empirical absorption process, of which the enthalpy change DH was -4.4 kJ/mol. The fitting molar ratio of D301R (functional group) to Re(Ⅶ) was about 1:1.

Shu et al. utilized an anion exchange resin (D318) to concentrate Re(Ⅶ) selectively and studied the mechanism during the process [36]. At pH of 5.2, the time required for the equilibrium of absorption was 2 h, while the absorption rate of Re(Ⅶ) on resin D318 was independent of temperature (ranges between 298– 313 K). The static and the dynamic absorption capacities of the resin were 351.4 and 366.5 mg/g, respectively, for the temperatures of 298 and 313 K. The absorption behavior obeyed the Freundlich equation and the rate-determining step was the diffusion of liquid film. It is easy to regenerate resin D318. Researchers found that potassium thiocyanate solution (KSCN, 2.0 mol/L) was the optimal strippant, and the percentage of desorption was up to 99.7%.

Chen et al. developed a kind of strong basic anion exchange resin which was functionalized with N-methylimidazolium and studied the performance of its absorption and separation for Re (Ⅶ) from Mo(Ⅵ), especially for copper arsenic filter cake [37]. Such resin was based on an earlier study, in which the Nmethylimidazolium functionalized strong basic anion exchange resin were synthesized and used for Cr(Ⅳ) extraction. At the pH 6.25, Re(Ⅶ) was separated from Mo(Ⅵ) effectively with the recovery yield of up to 93.3% for Re(Ⅶ), but of only 5.1% for Mo(Ⅵ). As for the recovery of copper arsenic filter cake sample, the yield could achieve 89.1% for Re(Ⅶ).

3.3. Solvent extractionCao et al. studied solvent extraction of rhenium from molybdenum in alkaline solution using a mixture of tributyl phosphate (TBP) and triotylamine (TOA) as extractants, where the complete separation of rhenium from molybdenum was possible if repeated extraction and stripping were conducted [38]. The results showed that the mixture of TOA (20%) and TBP (30%) diluted in kerosene was an efficient selective extract system (pH of 9.0 for the feed solution, room temperature, phase ratio 1:1), whose extraction efficiency of molybdenum was 1.7%, of rhenium was 96.8%, and the separation coefficient βRe/Mo was quite good (1.7 × 103). In addition, for the stripping process of rhenium into aqueous phase, the rhenium stripping yield could reach to 99.3% under conditions of phase ratio of 1:1 (O:A) for 10 min at 40 ℃ when 18% ammonia liquor was applied.

In 2010, Fang et al. measured the solvent extraction thermodynamics of Re(Ⅶ) with trioctyl amine (TOA) as the extractant [39]. This extraction system consisted of TOA, NH4ReO4, n-C7H16, HCl and H2O, and the standard extraction constants K0 were calculated by methods of Debye-Hückel extrapolation and Pitzer polynomial approximation. Thus the calculation results of the extraction thermodynamic properties were obtained.

Also in the year of 2010, Xiong et al. studied the solvent extraction system of Re(Ⅶ) and Mo(Ⅵ), i.e., mixtures of trialkylamine (N235, R3N, R = C8-C10) and tri-n-butyl phosphate (TBP) dissolved in heptane as the extractant, and the extracting mechanism inherent was investigated too [40]. The parameters such as stirring speed, temperature, concentrations of extractants were varied in order to observe the influences on extracting rates. It was confirmed that the extraction of Re(Ⅶ) occurred at the liquid-liquid interface, and the extraction kinetic was controlled by chemical reaction rate. Under the experimental conditions, the extraction rate equations and the rate-determining step were obtained, and thus the extraction rate constant was calculated. The extraction results of mixed system were compared with the system of N235 as extractant alone. The Re(Ⅶ) extraction rate was enhanced and the activation energy was decreased in case that the mixture of N235 and TBP was utilized.

In 2014, Zang and Xia et al. further studied amine N235 as extractant of rhenium from sulphuric acid solution and found the extraction effect was above 99% [41]. Molalities of perrhenate after extraction were measured at different ionic strengths which arranged from 0.2 to 2.0 (mol/kg) in aqueous phase and at a series of temperatures (278.15 K, 283.15 K, 288.15 K, 293.15 K, 298.15 K, and 303.15 K). The standard extraction constants K0 were thus obtained by the polynomial approximation method and some microcosmic phenomena were also investigated during the extraction process.

3.4. Extractive resinThere is a trend of developing a new method for higher selective separation of rhenium, where extractant impregnated resin (EIR) or extractive resin was applied by combination of characteristic advantages of ion exchange with extraction. The core design principle of EIR is based on the physical impregnation of an extractant into a porous resin. Moreover, it is easy to prepare the specific EIR depending on the requirements by choosing various extractants. In view of the mechanism of absorption, the impregnation of a reagent on the hydrophobic internal surface of macroporous nonionic resins can be conducted. For example, TEVA resin, which was made by Eichrom Technologies Inc., could act as a commercially available extraction chromatographic material and were used for rhenium separation [32]. This resin impregnated the aliphatic quaternary amine Aliquat 336 on AmberchromTM CG-71, where the latter played a role as the inert polymeric support [42].

The characteristics of P350 extractive resin for extracting rhenium from sulfuric acid solution were studied by Song et al. in 2003 [43]. The trace amount of rhenium was separated by a small chromatographic column, in which P350 extractive resin was fixed as immobile phase and sulfuric acid solution (2 mol/L) was eluted as mobile phase. The rhenium could also be stripped by sulfuric acid solution (4 mol/L).

In 2010, Jiang et al. prepared a novel trialkyl amine (N235) extractive resin and studied its extraction behavior of rhenium and molybdenum [44]. The influencing factors such as extraction time, concentrations of Re and Mo, pH of the extraction medium were investigated. The mechanism of extracting rhenium by the resin was analyzed through the equivalent molar series and conventional slope analysis method. Also, at different acid concentrations, rhenium could be separated from molybdenum (pH 6–10) or coextracted with molybdenum (pH 1).

3.5. Membrane separationIn 2000, Wang et al. developed an emulsion liquid membrane system for the separation and enrichment of rhenium [45]. This system was made up of a mobile carrier dibenzo-18-crown-6 (abbreviated as DBC), a surfactant (L113B), a solvent mixture of CCl4 and n-hexane, and the internal phase solution (NaClO4). They studied the stability of the emulsion liquid membrane and observed the effects of different factors such as operating temperature, concentrations (Re or H2SO4 in outer phase), and the ratios of two phases such as Rwe (water vs. emulsion) and Roi (CCl4 vs. Hexane). The best efficiency of rhenium enrichment could achieve 99.5% under an optimized condition. Additionally, cations such as Mo6+, Sn4+, Fe3+, Cu2+, K+, etc. and anions such as SO24-, NO3-, Cl-, etc. could not transport through the emulsion liquid membrane in this experiment, and hence ReO4- was separated from these ions. The method was suitable for the enrichment of minute quantities of rhenium in molybdenum concentrates and other rhenium-contained ores.

One year later (2001), Li et al. improved the system with some changes of the components [46]. In this case, the extraction system was made up of TBP, isoamyl alcohol, L113B, liquid paraffin, sulfonated kerosene and NH4NO3 in water. Experimental results showed that the extraction (enrichment) rate of rhenium could be more than 99.4% under the optimal condition, while the purity of Re (in the form of ReO4-) was above 99.9% after further treatment.

3.6. Novel methodsIn 2006, Lan et al. developed a resin-in-pulp (RIP) hydrometallurgical process on rhenium recovery after the molybdenite calcination leaching process, which was a combination of absorbing and eluting operations [47]. In detail, the improvement combined fresh water leaching and strong basic anion resin absorbing in one step. Then, Mo and Re was eluted by NH4OH and HNO3, respectively, and more than 90% of rhenium was recovered in the end. The resins they used were resin D216 and gel type resin 201 ×7. The resins were treated with NaOH, ion free water, washed with HCl and ion free water step by step. The eluting operations mentioned above were all conducted at pH of 7. After the RIP, the pregnant resins were separated from the pulp, washed with ion free water at first, and then the resins were eluted with specific solution (NH4Cl + NH4OH) to separate molybdenum compounds, followed with dilute HNO3 (1 mol/L) to separate the rhenium. The resins were finally washed with ion free water to regenerate themselves. The new RIP rhenium recovery process featured higher selectivity, short process, less costs and environmental compact compared to the typical process.

Dai et al. developed a new method to prepare periodic mesoporous organosilica (PMO) materials, on which ionic liquids were immobilized and ionic functional groups could be introduced accordingly. In addition, bridged N(3)-(3-trimethoxysilylpropyl-4, 5-dihydroimidazolium iodide and silsesquioxane N-(3-triethox-ysilylpropyl) were involved in the preparation [48]. The modified PMO materials were used as novel anion exchange resins for the separation of perrhenate anions in aqueous solution. Compared with previous cetyltrimethylammonium chloride (CTAC), 1-hexadecane-3-methylimidazolium bromide (CTAB) was demonstrated to be a more efficient surfactant template for the generation of PMO materials (1-hexadecane-3-methylimidazolium bromide immobilized).

Recently, Xiong et al. developed a novel microemulsion method to separate Re(Ⅶ) from hydrochloric acid medium. The extraction system contained multiple components such as N263, TBP, n-heptane and NaCl, where methyl trioctylammonium chloride (N263) acted two roles as surfactant and extractant at the same time [49]. The core extraction mechanism was a mix of anionexchange and complexation simultaneously, in which the actual two extracted species were assumed to be R3CH3N + ReO4- and (R3CH3N+Cl-)·(NH4ReO4) with a ratio of 1:3. Moreover, all of the extraction yields of Re(Ⅶ) were not less than 90% when the ratio of Re(Ⅶ) to Mo(Ⅵ) was distributed between 1:2.5, 1:5, 1:10 and 1:20 with the concentration of Re(Ⅶ) being fixed in solutions (20 mg/L).

The same group reported (2016) the recovery of Mo(Ⅵ) from Re (Ⅶ) on amino-functionalized mesoporous materials, which provided a new point of view for rhenium separation [50]. These materials were based on different mesoporous silicas, and the best type (SS5-1h-5.5@95) was prepared by anchoring of mesoporous silica substrate with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) via conventional methods and partitioned cooperative self-assembly process (PCSA process). It was showed that the SS5-1h-5.5@95-APTES had a high affinity for Mo(Ⅵ), and the maximum absorption capacity was evaluated as 194.32 mg/g at pH 1. Moreover, the absorption behavior, isotherm, kinetics and thermodynamics of Mo(Ⅵ) from Re(Ⅶ) on the SS5-1h-5.5@95-APTES were studied, where the absorption obeyed to Langmuir model. The absorbed complexes of Mo(Ⅵ) were assumed to be (SiO2-NH3)nHzMoxOy and/or (SiO2-NH2)·H2MoO4 during the ion exchange process.

Xiong et al. studied the extraction of Re(Ⅶ) and Mo(Ⅵ) in chloride media by using mixtures of bis-(3, 5-dimethylhexyl-4-methylhexyl) amine (N298) and tributylphosphate (TBP) [51]. There was a higher synergistic effect on Re(Ⅶ) than that of Mo(Ⅵ), and the maximal synergistic factor was obtained at the ratio of 1:9 (N298 vs. TBP) as a mixed extractant. Re(Ⅶ) was extracted in the form of (R2NH2Cl)3·HReO4·B, whereas Mo(Ⅵ) was extracted in the form of (R2NH2Cl)0.5·H2MoO4.0.25B. In contrast, the complexes formed during extraction were (R2NH2Cl)3·HReO4 and (R2NH2Cl)3·H2MoO4 by N298 alone, respectively. Furthermore, the formation constants and extraction mechanism were determined. Molybdenum and rhenium could be effectively separated by the mixtures at the pH values ranging from 1 to 10. So it was preferable to separate Mo(Ⅵ) from Re(Ⅶ) at high concentrations of N298 at first, and then to extract Re(Ⅶ) at low levels of N298.

Recently, Shen et al. investigated the extraction of ReO4- and TcO4- by ionic liquids (ILs) systematically [52]. The results indicated that ReO4- and TcO4- could be extracted either by imidazolium or quaternary ammonium ILs efficiently via anionexchange mechanism. Moreover, PF6-based ILs showed a higher extraction efficiency of ReO4-and TcO4- than NTf2-based ILs. The extraction efficiency would increase if the chain length of IL's cation was extended, while IL's identical anion was fixed. The addition of HNO3 and IL's anion in aqueous phase decreased the extraction efficiency, albeit the introduction of IL's cation led to an increase of the extraction efficiency. The ReO4- ions were selectively extracted by either [N6, 444][NTf2] or [C8mim][PF6] from simulated solution if it contained lower concentration of nitric acid. The ReO4- could be stripped effectively from [C8mim][PF6] and [N6, 444][NTf2] by aqueous KPF6 and LiNTf2 solutions, respectively.

4. Conclusion and outlookMost of the industrial processes related to the production of rhenium involve the use of either elevated temperatures, pressures, large amounts of organic reagents/extractants or the combination of them. Thus, it is imperative that the extraction and recovery of rhenium should be as effective and economical as possible. Some feasible advances of industrial production for the higher efficient processes are proposed as follows.

The roasting of molybdenum concentrates is an exothermic process with temperatures of 900–950 K. The present scrubbing process of flue gases were relatively inefficient, i.e. capturing only 25% of the total rhenium. Thus, increasing the recovery efficiency of rhenium from roasting flue dusts makes itself an estimable research opportunity. For example, through update of the scrubbing equipment, recoveries could be increased to approximately 80% in pilot scale [16].

Alternatively, another practical option for rhenium recovery may involve the industrial utilization of hydrometallurgical pressure oxidation of molybdenum concentrates. The enhanced recoveries of this process may make it another viable choice to traditional roasting processes, though it involves the use of elevated temperatures/pressures and additional reagents. Hence the research related to hydrometallurgical oxidation in relatively low temperature/pressure is ongoing in industry.

As a following process to roasting or pressure oxidation, the need for efficient separation of aqueous rhenium is more important and urgent. A variety of techniques have been investigated in both industry and laboratory, including ion exchange, solvent extraction, and many other innovative absorption/separation materials. With the development of higher selectivity resins and extractants used in ion exchange and solvent extraction, respectively, these two methods present themselves more practical and applicable in industrial production. Meanwhile, other methods need to be studied further in laboratory such as extractive resins, membrane separation, and so on. These methods may be the next-generation separation/enrichment choices in the future owing to higher selectivity and lower price/consumption.

Another way to meet the increasing demands of rhenium is the reprocessing of rhenium-laden manufacturing scrap and end-oflife materials, such as Pt-Re catalysts and Ni-based super alloys. Since it is a new part of the rhenium industry, the research opportunities are almost boundless. The principal problem is the dissolution of these super alloys or catalysts in either complete or selective way [16].

As China is becoming the major producer and consumer of rhenium with the fast growth of economics and industries, it is an urgent need to update the separation/enrichment techniques in China's rhenium industry [24].

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21472194, 21701073 and 21772202) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. lzujbky-2017-12).

| [1] |

T. A. Millensifer, Rhenium and rhenium compounds, in: K. Othmer (Eds. ), Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, John Wiley and Sons, 2010, pp. 1-21.

|

| [2] |

H. Chong, C. Qishen, Y. Li, Q. Liu, China Min. Mag. 9 (2014) 9-11. |

| [3] |

National Bureau of Statistics of China, Statiscal Year Books, 2016.

|

| [4] |

Dobrzanska-Danikiewicz A.D., W. Wolany, Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 82 (2016) 70-78. DOI:10.5604/18972764 |

| [5] |

G. Mao, Q. Huang, C. Wang, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017 (2017) 3549-3564. DOI:10.1002/ejoc.v2017.25 |

| [6] |

Y. Wang, L. Zhang, Y. Yang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 18048-18051. DOI:10.1021/ja410195j |

| [7] |

X. Jin, X. Yang, Y. Yang, C. Wang, Org. Chem. Front. 3 (2016) 268-272. DOI:10.1039/C5QO00336A |

| [8] |

X. Geng, C. Wang, Org. Biomol. Chem. 13 (2015) 7619-7623. DOI:10.1039/C5OB01121C |

| [9] |

G. Mao, B. Jia, C. Wang, Chin. J. Org. Chem. 35 (2015) 284. DOI:10.6023/cjoc201409027 |

| [10] |

X. Geng, C. Wang, Org. Lett. 17 (2015) 2434-2437. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00938 |

| [11] |

H. Gu, C. Wang, Org. Biomol. Chem. 13 (2015) 5880-5884. DOI:10.1039/C5OB00619H |

| [12] |

D. E. Polyak, US Geological Survey Minerals Year Book, U. S. Department of the Interior, 2016, pp. 136-137.

|

| [13] |

S.G. Tessalina, M.A. Yudovskaya, I.V. Chaplygin, J.L. Birck, F. Capmas, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72 (2008) 889-909. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2007.11.015 |

| [14] |

L. Li, Y. Liu, W. Zhang, L. Jiang, W. Zhang, China Molybd. Ind. 40 (2016) 1-6. |

| [15] |

H. Li, X. He, Y. Zhao, et al., Precious Met. 35 (2014) 77-81. |

| [16] |

C.D. Anderson, P.R. Taylor, C.G. Anderson, Miner. Metall. Proc. 30 (2013) 59-73. |

| [17] |

A. Sutulov, Molybdenum Extractive Metallurgy, University of Concepcion, Santiago, 1965.

|

| [18] |

D.W. Fang, S.L. Zang, Y.L. Song, J. Liaoning Univ. 43 (2016) 233-237. |

| [19] |

W. Jilie, Precious Met. 23 (2002) 57-61. |

| [20] |

J. J. C. C. Ltd., http://money.finance.sina.com.cn/corp/view/vCB_AllBulletinDetail.php?stockid=600362&id=3165494, 2016.

|

| [21] |

P. J. Loferski, US Geological Survey Minerals Year Book, National Minerals Information Center, U. S. Geological Survey, 989 National Center, 2017, pp. 1-5.

|

| [22] |

S. P. M. C. Ltd., http://money.finance.sina.com.cn/corp/view/vCB_AllBulletinDetail.php?stockid=600459&id=3225871, 2016.

|

| [23] |

Y. Wang, Precious Met. 33 (2012) 48-64. |

| [24] |

X. He, J. Guo, H. Wang, et al., Precious Met. 34 (2013) 82-89. |

| [25] |

E. D. Polyak, Minerals Yearbook, U. S. Department of the Interior, 2015, pp. 1-6.

|

| [26] |

A. Chmielarz, K. Litwinionek, Development of the Technology for the Recovery of Rhenium from Polish Copper Smelters, Hamburg DE, 2010.

|

| [27] |

Z.S. Abisheva, A.N. Zagorodnyaya, N.S. Bekturganov, Hydrometallurgy 109 (2011) 1-8. DOI:10.1016/j.hydromet.2011.04.014 |

| [28] |

V. J. Ketcham, E. J. Coltrinari, W. W. Hazen, in: U. S. P. a. T. Offce (Eds. ), Kennecott Utah Copper Corporation (Salt Lake City, UT), 2000.

|

| [29] |

B. T. Waterman, S. N. Dixon, T. L. Morelli, G. Owusu, S. T. Ormsby, in: U. S. P. a. T. Office (Eds. ), Freeport-McMoran Corporation (Phoenix, AZ, US), 2013.

|

| [30] |

A.V. Naumov, Russ. J. Non-Ferr. Met. 48 (2007) 418-423. DOI:10.3103/S1067821207060089 |

| [31] |

V.A. Sinegribov, K.V. Sotskov, A.A. Yudin, Theor. Found. Chem. Eng. 41 (2007) 593-598. DOI:10.1134/S0040579507050235 |

| [32] |

M. Lučaníková, Kučcera J., F. Šebesta, J. Radioanal, Nucl. Chem. 277 (2008) 479-485. DOI:10.1007/s10967-007-7153-8 |

| [33] |

D.G. Pearson, S.J. Woodland, Chem. Geol. 165 (2000) 87-107. DOI:10.1016/S0009-2541(99)00161-8 |

| [34] |

C. Xiong, C. Yao, X. Wu, Hydrometallurgy 90 (2008) 221-226. DOI:10.1016/j.hydromet.2007.10.011 |

| [35] |

X. Wu, Z. Shu, Chin. J. Inorg. Chem. 25 (2009) 1227-1232. |

| [36] |

Z. Shu, M. Yang, Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 18 (2010) 372-376. DOI:10.1016/S1004-9541(10)60233-9 |

| [37] |

M. Jia, H. Cui, W. Jin, et al., J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 88 (2013) 437-443. DOI:10.1002/jctb.2013.88.issue-3 |

| [38] |

Z.F. Cao, H. Zhong, Z.H. Qiu, Hydrometallurgy 97 (2009) 153-157. DOI:10.1016/j.hydromet.2009.02.005 |

| [39] |

D.W. Fang, X.J. Gu, Y. Xiong, et al., J. Chem. Eng. Data 55 (2010) 424-427. DOI:10.1021/je900402w |

| [40] |

Y. Xiong, Z. Lou, S. Yue, et al., Hydrometallurgy 100 (2010) 110-115. DOI:10.1016/j.hydromet.2009.10.014 |

| [41] |

D.W. Fang, W.J. Shan, Q. Yan, et al., Fluid Phase Equilibr. 383 (2014) 1-4. DOI:10.1016/j.fluid.2014.09.012 |

| [42] |

J.K. Moon, Y.J. Han, C.H. Jung, E.H. Lee, B.C. Lee, Korean J. Chem. Eng. 23 (2006) 303-308. DOI:10.1007/BF02705732 |

| [43] |

J.R. Song, Z.X. Gong, Y.Q. Deng, J. East China Geol. Inst. 26 (2003) 274-278. |

| [44] |

K.X. Jiang, Y.C. Zhai, Y. Xiong, X.F. Wang, Nonferr. Met. (Extr. M.) 2 (2010) 35-37. |

| [45] |

X. Wang, Y. Li, L. Li, China Molybd. Ind. 24 (2000) 38-41. |

| [46] |

Y. Li, L. Li, X. Wang, China Molybd. Ind. 25 (2001) 23-26. |

| [47] |

X. Lan, S. Liang, Y. Song, Hydrometallurgy 82 (2006) 133-136. DOI:10.1016/j.hydromet.2006.03.007 |

| [48] |

B. Lee, H.J. Im, H. Luo, E.W. Hagaman, S. Dai, Langmuir 21 (2005) 5372-5376. DOI:10.1021/la050313d |

| [49] |

Z. Lou, X. Cui, S. Zhang, et al., Hydrometallurgy 165 (2016) 329-335. DOI:10.1016/j.hydromet.2016.01.004 |

| [50] |

W. Shan, Y. Shu, H. Chen, et al., Hydrometallurgy 165 (2016) 251-260. DOI:10.1016/j.hydromet.2016.02.005 |

| [51] |

Y. Xiong, W.J. Shan, Z.N. Lou, et al., J. Phase Equilibr. Diff. 32 (2011) 193-197. DOI:10.1007/s11669-010-9847-9 |

| [52] |

Y. Song, T. Sun, Q. Chen, X. Shen, Sci. Acta, Nat. Univ. Pekinensis(2017), 1-7. |

2018, Vol. 29

2018, Vol. 29