b State Key Laboratory of Hollow-fiber Membrane Materials and Membrane Processes, School of Environmental and Chemical Engineering, Tianjin Polytechnic University, Tianjin 300387, China

The high energy density battery is ever-increasing demanded due to large using of electronic gadgets ranging from portable electronics to electrical vehicles and smart grids [1]. Over the years, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) is considered as one of the most promising devices to fulfill the energy demands thanks to their high energy density, long cycle life and good environmental benignity [2]. However, large-scale market penetration of LIBs raises much concern, such as high cost of lithium resource ($5000 ton-1) as well as low abundance of Li in the earth's crust (20 mg/kg) [3, 4]. Therefore, to develop low cost, high safety and desirable cycling performance rechargeable batteries with natural abundance is regarded as one of the current priorities [5]. So far, much effort has recently been dedicated to sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) because of the nature abundance of sodium resources and the similar physical and chemical properties between sodium and lithium [6]. Therefore, SIBs is considered as one of the most promising candidates for the next-generation energy storage devices. But theoretically speaking, Na has some disadvantages for SIBs regarding that the radius of Na+ (1.02 Å) is larger than Li+ (0.76 Å), Na is more than 3 times heavier than Li (22.99 g/mol vs. 6.94 g/mol) and the standard electrochemical potential of Na (2.71 V) is lower than Li (3.04 V) with respect to SHE [7]. These disadvantages make that the performance of present SIBs may not reach expectation. It is known that the battery performance characteristics such as specific capacity are mainly determined by electrode materials. Therefore, the major challenge in advancing SIBs technology lies in finding suitable electrode materials, including cathode and anode materials [8].

Among the materials as anode for SIBs, tin mono sulphide (SnS) is considered as one of the most promising materials for SIBs due to its unique layer structure and high theoretical capacity (1022 mAh/g) through a sequential conversion (355 mAh/g) and alloying-dealloying reaction (667 mAh/g) [9]. However, SnS as anode for SIBs performs unsatisfied cycling performance due to slow reaction kinetics of large-radius Na+, huge expansion during charge and discharge process and inferior conductivity [10, 11]. Introducing conductive agents to SnS system could accommodate the volume change and improve the conductance of the active materials, which is an effective way to solve the problems of SnS [12]. So far, amorphous carbon [9], carbon powder [11] and graphene [13] are main conductive agents composited with SnS. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) is a newly one-dimensional material with remarkably mechanical properties (tensile strength as high as 63 GPa), electrical property (conductivity of 10, 000 cm2 V-1 s-1) and extremely lightweight, which is an ideal hybrid for improving electrochemical performance of electrodes [14, 15]. Ding et al. reported that the SnS2/CNTs electrode synthesized by a solvothermal method exhibits a superior capacity (180 mAh/g at 1280 mA/g) to that of pure SnS2 electrode (15 mAh/g at 1280 mA/g) [16]. Therefore, it is promising to develop a CNTs improved SnS composite towards the high electrochemical performance for SIBs. However, to the best knowledge, there are hardly any reports about this topic.

Herein, we synthesized SnS/CNTs composite anode by a facile one-step solvothermal method. In SnS/CNTs composite, SnS nanoparticles distribute on the surface of CNTs. The reversible capacity of SnS/CNTs composite electrode (365 mAh/g at 50 mA/g after 50 cycles) is three times higher than that of pure SnS electrode (115.9 mAh/g). When increasing the current density to 500 mA/g, SnS/CNTs composite electrode still exhibits a reversible capacity up to 210 mAh/g after 100 cycles, nearly two times higher than that of the pure SnS electrode. Rate performance of the SnS/CNTs composite electrode is also superior to that of pure SnS electrode at different current densities from 50 mA/g to 800 mA/g. The enhanced electrochemical performance of SnS/CNTs composite originates from the adding of CNTs as both the flexible and conductive structure supporter and the steric hindrance agent to obtain the SnS with small nanoscale diameter and the high surface area, which could buffer the volume change of electrode during charge and discharge process, provide high electronic conductivity, shorten Na+ diffusion length and facilitate the sufficient electrode-electrolyte contacting.

SnS/CNTs composite was synthesized by a facile solvothermal reaction. The schematic illustration of the synthesis process of SnS/CNTs composite is shown in Fig. S1 (Supporting information). Firstly, 50 mg of CNTs (TNM1, Chengdu, China) were homogeneously dispersed into 60 mL of ethyleneglycol (EG) by ultrasonication for 1 h. Then, 1.25 mmol of SnCl2·5H2O, 3.75 mmol of thiourea and 1.25 mmol of citric acid were added to the CNTs suspension and stirred for 30 min. After that, the mixture was transferred to a 100 mL Telfon-lined sealed autoclave and heated at 190 ℃ for 18 h. Lastly, the precipitates were cooled to room temperature naturally, and then centrifugated and washed with deionized (DI) water and absolute ethanol repeatedly for several times. The final SnS/CNTs composite products were obtained by drying the collected samples at 60 ℃ for 10 h under vacuum (SnS was prepared without adding CNTs in the precursor). The sections of characterization and electrochemical measurements could be seen in Supporting information.

As shown in SEM images of SnS/CNTs composite (Figs. 1a–c), some SnS nanoparticals are observed on the surface of CNTs. The size of SnS nanoparticals is less than 10 nm as shown in HRTEM image of SnS/CNTs composite (Fig. 1d). In addition, HRTEM image also shows the interplaner distance of 0.212, 0.284 and 0.293 nm for the (210), (111) and (101) plane of the orthorhombic SnS (JCPDS No. 39-0354) and lattice plane of 0.340 nm for the (002) plane of graphite-like structure of CNTs. It indicates the effective compositing of SnS nanoparticals with CNTs. For comparison, pure SnS synthesized without the adding of CNTs is flower-like morphology with the size ranging from 1–5 μm (Fig. 1e). These SnS flowers are actually agglomerated by many SnS nanosheets with the thickness of 10–30 nm (Fig. 1f). It is obvious that the adding of CNTs not only facilitates the formation of SnS with small nanoscale diameter, but also promotes the distribution of SnS nanoparticals on the CNTs backbone, which are benefit for reducing the pathway of Na+ diffusion and increasing the conduction of SnS/CNTs composite [17, 18].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (a and b) SEM images, (c) TEM image and (d) HRTEM image of SnS/CNTs composite; (e, f) SEM images of pure SnS. | |

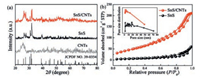

The XRD patterns of SnS/CNTs composite, pure SnS and CNTs are shown in Fig. 2a. All the diffractions of SnS are matched well with orthorhombic SnS (Space group: Pbnm, JCPDS No.39-0354) with lattice constants of a = 4.3291 Å, b = 11.1923 Å, and c = 3.9838 Å. The pattern of SnS/CNTs composite exhibits almost the same peaks as pure SnS except for 2θ = 26°, corresponding to the (002) plane of CNTs [19]. The thermogravimetric (TG) curves of SnS/CNTs composite is shown in Fig. S2 (Supporting information). The CNTs contents of SnS/CNTs composite could be roughly calculated to be 30.5% by weight. The surface area of SnS/CNTs composite is estimated up to 172 m2/g, nearly 8 times higher than that of pure SnS (22 m2/g) (Fig. 2b). The pore volume of SnS/CNTs composite (0.31 cm3/g) is also much large than that of pure SnS (0.09 cm3/g). The higher surface area and larger pore volume of SnS/CNTs composite synthesized with the adding of CNTs are benefit for increasing electrode-electrolyte contacting and shortening Na+ diffusion length, which are important to achieve high electrochemical performance for SIBs [20, 21].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) XRD patterns of SnS/CNTs composite, pure SnS and CNTs. (b) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and pore size distributions of SnS/CNTs composite and pure SnS. | |

To determine the sodium-ion storage performance of SnS/CNTs composite electrode, both cyclic voltammetry (CV) and galvanostatic charge-discharge test were conducted. The CV curve of SnS/CNTs composite electrode is shown in Fig. 3a. During the first cycle, a broad reduction peak at around 0.9 V is observed, which could be assigned to two aspects. One aspect is the conversion of SnS to Sn and amorphous NaxS, analogous to the conversion reaction of tin-sulfide as anode for LIBs [11, 22, 23]. The other one is the formation of SEI and the decomposition of electrolyte [24-26]. This irreversible reduction peak disappears in the following cycles which are associated with the irreversible specific capacity of SnS/CNTs composite electrode. The reduction peaks below 0.8 V and the oxidation peaks at 1.2 V and below 0.5 V can be attributed to the alloying and dealloying process of Na and Sn [11]. From the second cycle onwards, the CV curves almost overlap, which can be identified in the charge-discharge voltage profiles (Fig. 3b), indicating good cycling performance of SnS/CNTs composite electrode.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) Cyclic voltammograms of SnS/CNTs composite electrode; (b) Galvanostatic discharge-charge profiles of SnS/CNTs composite electrode; (c) Cycling performance and coulombic efficiency of SnS/CNTs composite, pure SnS and CNTs electrodes at 50 mA/g; (d) Rate performance of SnS/CNTs composite, pure SnS and CNTs electrodes; (e) Cycling performance and coulombic efficiency of SnS/CNTs composite and SnS electrodes at 500 mA/g; (f) Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of SnS/CNTs composite, pure SnS and CNTs samples. | |

The sodium-ion storage property of SnS/CNTs composite electrode was investigated in the potential range of 0.01–2 V (versus Na/Na+) at 50 mA/g. For comparison, pure SnS and CNTs electrodes were also tested under the same conditions (Fig. 3c). The initial discharge capacity of SnS/CNTs composite electrode is as high as 833 mAh/g, corresponding to 81.5% of the theoretical capacity of SnS (1022 mAh/g). It is much higher than that of pure SnS electrode (315.9 mAh/g). The initial coulombic efficiencies of SnS/CNTs composite and pure SnS electrodes are only 41.7% and 42.8%, which are in accordance with previous reports [25, 26]. Such low coulombic efficiencies are due to the formation of SEI [27]. SnS/CNTs composite electrode stabilizes at around 365 mAh/g after 50 cycles, which is 3 times higher than that of pure SnS electrode (115.9 mAh/g). In addition, the coulombic efficiency of SnS/CNTs composite electrode increases from 96% for the 5th cycle to 110% for the 50th, indicating stable cycling performance. For pure CNTs electrode, the capacity is 50 mAh/g after 50 cycles, which agrees with the previous report [28]. It is obvious that the electrochemical performance of SnS/CNTs composite electrode is much better than that of pure SnS electrode. The enhanced electrochemical performance of SnS/CNTs composite is benefit from the adding of CNTs as both the flexible and conductive structure supporter and the steric hindrance agent to obtain the SnS with small nanoscale diameter and the high surface area, which could buffer the volume change of electrode during charge and discharge process, provide high electronic conductivity, shorten Na+ diffusion length and facilitate the sufficient electrode-electrolyte contacting.

The rate performances of samples once again confirm the advantage of the SnS/CNTs composite synthesized with the adding of CNTs. SnS/CNTs composite electrode could deliver stable capacity of ca. 420, 350, 270 and 200 mAh/g at 50, 100, 200 and 500 mA/g (Fig. 3d). Even increasing current density to 800 mA/g, SnS/CNTs composite electrode is able to maintain stable cyclability capacity of 184 mAh/g, which is better than that of pure SnS electrode (65 mAh/g at 800 mAh/g). When cycled back to 50 mA/g, the reversible capacity of SnS/CNTs composite electrode recovers to 415 mAh/g, showing a stable structure tolerance for rapid Na+ insertion/extraction. The cyclability of SnS/CNTs composite electrode at a high current density (500 mA/g) is compared to pure SnS as shown in Fig. 3e. SnS/CNTs composite electrode performs a reversible capacity up to 210 mAh/g with coulombic efficiency of nearly 100% after 100 cycles. The reversible capacity of SnS/CNTs composite is two times higher than pure SnS (108 mAh/g).

The electrochemical performance of SnS/CNTs composite is more excellent than that of pure SnS electrode as observed above. To further understand the effect of synthesized by the adding of CNTs and kinetics of electrode process, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were performed for SnS/CNTs composite, pure SnS and CNTs electrodes. As depicted in Fig. 3f, all curves are apparently including a medium-high-frequency semicircle and a low-frequency line, which corresponding to the charge-transfer impendance (Rct) and Na+ diffusion process through active materials [29]. The semicircle diameters of SnS/CNTs composite electrode is smaller than that of pure SnS electrode, indicating the charge transfer resistance (Rct) of SnS/CNTs composite electrode (273.6 Ω) is much lower than that of SnS electrode (344.6 Ω). The low-frequency line of SnS/CNTs composite electrode is steeper than that of pure SnS electrode, suggesting faster Na+ diffusion. The EIS performance of SnS/CNTs composite electrode indicates that the adding of CNTs could accelerate Na+ diffusion and improve the conductivity, which can lead better electrochemical performance as observed above.

In summary, SnS/CNTs composite with SnS nanoparticles anchored on the surface of CNTs is synthesized by a simple solvothermal reaction. The diameter of SnS is less than 10 nm. The SnS/CNTs composite electrode exhibits higher sodium-ion storage capacity and more excellent cyclability (365 mAh/g at 50 mA/g for 50 cycles) as well as rate capability than that of pure SnS electrode. Even increasing the current to 500 mA/g, SnS/CNTs composite electrode still delivers a reversible capacity up to 210 mAh/g after 100 cycles, which is two times higher than that of pure SnS electrode. The enhanced electrochemical performance of SnS/CNTs composite originates from the adding of CNTs as both the conductive supporter and the steric hindrance agent, which could enable the structural stabilization, increase the electrolyte-electrode contacting, enhance Na+ effective diffusion, and finally improve the electrochemical performance of SnS/CNTs composite electrode.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Nos. 51572192, 51472179) and General Program of Municipal Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (Nos. 17JCYBJC17000, 17JCYBJC22700).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associatedwith this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2017.06.019.

| [1] |

C. Liu, F. Li, L.P. Ma, et al., Adv. Mater. 22(2010) E28-62. DOI:10.1002/adma.v22:8 |

| [2] |

L. Ji, Z. Lin, M. Alcoutlabi, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 4(2011) 2682. DOI:10.1039/c0ee00699h |

| [3] |

M.D. Slater, D. Kim, E. Lee, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 23(2013) 947-958. DOI:10.1002/adfm.v23.8 |

| [4] |

N.S. Choi, Z. Chen, S.A. Freunberger, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51(2012) 9994-10024. DOI:10.1002/anie.201201429 |

| [5] |

E. Cho, K. Song, M.H. Park, et al., Small 12(2016) 2510-2517. DOI:10.1002/smll.201503168 |

| [6] |

V. Palomares, P. Serras, I. Villaluenga, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 5(2012) 5884. DOI:10.1039/c2ee02781j |

| [7] |

M.H. Han, E. Gonzalo, G. Singh, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 8(2015) 81-102. DOI:10.1039/C4EE03192J |

| [8] |

J. Kim, D.H. Seo, H. Kim, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 8(2015) 540-545. DOI:10.1039/C4EE03215B |

| [9] |

H.L. Wu, L.F. Xiao, J.F. Qian, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 2(2014) 16424-16428. DOI:10.1039/C4TA03365E |

| [10] |

D.D. Vaughn, O.D. Hentz, S. Chen, et al., Chem. Commun. 48(2012) 5608-5610. DOI:10.1039/c2cc32033a |

| [11] |

S.H. Choi, Y.C. Kang, Nano Res. 8(2015) 1595-1603. DOI:10.1007/s12274-014-0648-z |

| [12] |

L. Zhou, K. Zhang, J. Sheng, et al., Nano Energy 35(2017) 281-289. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2017.03.052 |

| [13] |

L. Wu, H. Lu, L. Xiao, et al., J. Power Sources 293(2015) 784-789. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.06.015 |

| [14] |

S.H. Hong, S. Myung, Nat. Nano 2(2007) 207-208. DOI:10.1038/nnano.2007.89 |

| [15] |

M.F. Yu, O. Lourie, M.J. Dyer, et al., Science 287(2000) 637-640. DOI:10.1126/science.287.5453.637 |

| [16] |

Y. Ren, J. Wang, X. Huang, et al., Mater. Lett. 186(2017) 57-61. DOI:10.1016/j.matlet.2016.09.089 |

| [17] |

W. Wei, F.F. Jia, K.F. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 28(2017) 324-328. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2016.09.003 |

| [18] |

J. Lu, C. Nan, L. Li, et al., Nano Res. 6(2012) 55-64. |

| [19] |

G. Zhou, L. Li, Q. Zhang, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15(2013) 5582-5587. DOI:10.1039/c3cp50221j |

| [20] |

N. Zhang, X. Han, Y. Liu, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 5(2015) 1401123. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201401123 |

| [21] |

Z. Hu, L. Wang, K. Zhang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53(2014) 12794-12798. DOI:10.1002/anie.201407898 |

| [22] |

D.H. Youn, S.K. Stauffer, P. Xiao, et al., ACS Nano 10(2016) 10778-10788. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.6b04214 |

| [23] |

M. Zhang, D. Lei, X. Yu, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 22(2012) 23091. DOI:10.1039/c2jm34864k |

| [24] |

T.F. Zhou, W.K. Pang, C.F. Zhang, et al., ACS Nano 8(2014) 8323-8333. DOI:10.1021/nn503582c |

| [25] |

B. Guo, J. Shu, K. Tang, et al., J. Power Sources 177(2008) 205-210. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.11.003 |

| [26] |

D. Zhou, Y. Liu, W.L. Song, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 316(2017) 645-654. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2017.02.008 |

| [27] |

X. Li, Y. Zhong, M. Cai, et al., Electrochim. Acta 89(2013) 387-393. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2012.11.097 |

| [28] |

X.F. Luo, C.H. Yang, Y.Y. Peng, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 3(2015) 10320-10326. DOI:10.1039/C5TA00727E |

| [29] |

P. Guo, H. Song, X. Chen, Electrochem. Commun. 11(2009) 1320-1324. DOI:10.1016/j.elecom.2009.04.036 |

2018, Vol. 29

2018, Vol. 29