b State Key Laboratory of Silicate Materials for Architectures, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan 430070, China

Room temperature ionic liquids (RTILs) are fascinating materials with low volatility, high thermal stability, wide electrochemical window, decent conductivity and excellent lubricity [1-5]. Many important applications of RTILs, ranging from catalysis, lubrication, CO2 capture, energy storage to heat-exchange nanofluids [6-17], involve RTIL/solid interface. Understanding the wettability of nanometer-thick RTILs on the solid surface is critical to uncovering the molecular arrangement of RTILs at the liquid/solid interface. Moreover, the learning here will enable us to optimize device performance and manufacturing process. One example is RTILs confined in nanoporous solid support, in which RTILs need to be filled into the nanopores, for application in energy storage [7, 8] and CO2 capture [16, 17]. As schematically shown in Fig. 1, the different wettability of nano-sized RTIL on the solid will result in very different liquid-solid interface geometry and thus impact the pore filling, i.e., manufacturing process greatly. In super-capacitors, RTILs are promising electrolytes due to their broad electrochemical window, low volatility and non-flammability. As shown in Eq. (1), the double-layer capacitance (C) is determined by the electrolyte dielectric constant (εr), the dielectric constant of the vacuum (ε0), the charge separation distance (d) and the electrode/RTIL interfacial area (A) [18].

|

(1) |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Effect of the nanoscale wettability of RTILs on the manufacturing process of nano-confined RTILs in nanoporous matrix. | |

To increase the interfacial area and thus increase the capacitance, nanoporous carbon electrodes are being utilized now [18]. However, if the RTILs do not wet the electrode surface completely inside the nanopores (Fig. 1), the desired increase of the capacitance will not be achieved.

Indeed, the wettability of nanometer-thick RTILs on solid surfaces is important for many other applications. For example, due to their high thermal stability and good lubricity, RTILs are promising material candidate as nanometer-thick media lubricant for hard disk drives (HDDs) [15, 19], where the lubricant is placed on top of an amorphous carbon (AC) overcoat [20]. Our recent research showed that the enhanced wettability of nanometer-thick RTILs will significantly reduce the friction [19]. Another important application for the RTIL/solid interface is heat-exchange nanofluid, which has higher thermal conductivity than conventional heattransfer fluid due to the high thermal conductivity of the solid nanoparticles, such as alumina, multi-wall carbon nanotube (MWCNT), graphene and carbon black [12-14]. Due to the high thermal stability and low volatility, RTIL is promising as the dispersion liquid in the nanofluids [12, 13], wherethe enhanced wetting of RTILs on the nanoparticle surface will increase the thermal conductivity of the nanofluid [12-14, 21, 22]. In catalysis application, immobilization of nanometer-thick RTILs on the silica nanoparticles is required [23] and the good wettability of RTILs on the solid support is essential to the success of the process. In electrode position of metals, wetting of RTILs reduces the transport of the reactants at the electrolyte (RTIL)/electrode (solid) interface and thus slows down the growth of nuclei, resulting in nanocrystalline deposit [10].

Given the importance of the wettability of nanometer-thick RTILs on various solids, there have been increasing research interests in the topic in the past two decades. In the current review, we will discuss the recent progress with the emphasis on RTIL/ mica and RTIL/graphite interfaces. Both mica and graphite have been commonly utilized as the model solid surfaces in surface science community. Moreover, they represent electrically charged and neutral solids, respectively, in different applications involving RTIL/solid interfaces. Following the introduction, the research works on the macroscopic wettability of RTILs on solids will be reviewed briefly. Then the difference between macroscopic and nanoscopic wettability will be discussed and the progress on the wettability of nanometer-thick RTILs will reviewed. For RTIL/mica interface, the focus will be the unexpected effect of water. For RTIL/ graphite interface, the proposed governing mechanism of π-π+ stacking will be discussed. Lastly, the future research directions will be briefly discussed.

At macro-scale, the wettability of a liquid on a solid surface has been characterized by contact angle (CA) as described by Young's equation [24] (Eq. (2)) and schematically shown in Fig. 2. Here γlv, γsv and γsl is the liquid surface tension, solid surface tension and liquid-solid interface tension, respectively. θ is defined as the contact angle and it increases with the decrease of the wettability of the liquid on the solid. When the contact angle is 0°, the liquid wets the solid surface completely and a uniform film of liquid will be formed on the solid surface. If the contact angle is 180°, the liquid dewets the solid surface completely and a perfect spherical liquid droplet is formed. When the contact angle is between 0° and 180°, the liquid partially wets the surface.

|

(2) |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Schematic of Young's equation. | |

Although RTILs are salts composed of ions, they are liquids instead of crystalline solids at ambient temperatures. This is because the ions in RTILs are sterically-mismatched anions/cations and, as a result, Coulombic attractions are dampened and lattice structure is not formed [25]. The chemical structure of cations and anions of commonly used RTILs are shown in Fig. 3. In general, the cations have aliphatic hydrocarbon substitutes and anions could be either hydrophilic or hydrophobic. As a result, the chemical structure of RTILs is between salts and molecular liquids. The surface tension of RTILs has been extensively studied and the experimental data indicates that the surface tensions of known RTILs are between alkane and water [26, 27]. Indeed, most of the RTILs, i.e., hydrophobic ones, have the surface tension close to alkane, which suggests that, at the RTIL-air interface, the molecular orientation of RTIL is in such a way that the hydrophobic segments orient toward the air. Surprisingly, there has been only limited research on the contact angle of RTILs on solids. The systematic research on the effect of chemical structure of cations, anions and solid surfaces is yet to be completed. More detailed discussions on this topic, which is not the focus of the current review, are available in two recent reviews [26, 27].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Chemical structures of ionic liquids. Reproduced with permission [5]. Copyright 2009, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

Here, only two points are briefly discussed. First, it is interesting to compare the contact angle of RTILs to molecular liquids with the similar surface tension. Gao and McCarthy [28] reported that smooth surfaces of various chemical composition exhibit lower contact angles with RTILs than with water and that scale with liquid surface tension values. Interestingly, they also found that contact angles of RTILs on rough perfluoroalkyl surfaces are indistinguishable from those of water and not dependent on liquid surface tension [28]. Cione et al. [29] studied the wettability of a RTIL on thiol- and silane-based self-assembly monolayers and found that contact angles of RTILs are significantly larger than those of dicyclohexyl, a model molecular liquid with very similar (±1 mN/m) surface tension. The authors [29] attributed the difference to strong electrostatic interactions between ions within the RTIL drop and the resulting increase in the cohesion forces. Another way to interpret this result is that the RTIL is more polar than dicyclohexyl and this result in higher liquid-solid interfacial tension and thus increases the contact angle. Given the data available at this point, it remains unclear how the ionic nature of RTILs impacts the contact angle and how this can be manipulated by the tailoring the structure of cations and anions. Second, the experimental data [26, 27] also indicates that the contact angle of RTILs on some solids, especially the ones with high surface energy, could change significantly because of minor differences (such as water content change due to storage), which suggests that the RTIL-water-solid interaction is important.

When a liquid is confined to a rigid solid surface, the molecular organization of the liquid could be very different from that in the bulk liquid [25, 30]. Next to the solid surface, mobile liquid molecules are induced into discrete "solid-like" layers, which could extend to a few molecular diameters from the liquid-solid interface [30]. This liquid ordering, termed "solvation layers", is characterized by an oscillatory molecular density profile and has been observed for many liquids, including simple molecular liquids and polymer melts [30, 31]. It is believed that geometric factor (entropy) is critical to the formation of solvation layers since layering even occurs in the absence of attractive solid-liquid interactions [30]. It has been also proposed that the translational entropy available to the liquid molecules under spatial confinement decreases to the point at which it becomes thermodynamically favorable for the molecules to form ordered layering structure [14]. Meanwhile, the strong interfacial solid-liquid attraction, e.g., electrostatic force, promotes the layering structure [30]. When the size of the RTIL droplet is in the range of nanometers to tens of nanometers, where the solid-like layering of RTILs could occur, the macro-scale contact angle may or may not characterize the wettability anymore. If there is solid-like layering of the RTIL next to the solid substrate, the nano-scale contact angle is expected to be 0°, regardless of the macro-scale contact angle value. However, many factors, including RTIL/solid interaction, contamination and roughness, might impact the wettability of nanometer-thick RTILs. In this section, we will review the recent research works form others and us on RTIL/mica and RTIL/graphite interfaces.

When RTILs are next to some ceramic surfaces, e.g., silica, alumina, and mica, extended solid-like layering has been frequently observed [2, 15, 32-42]. Carmichael et al. [33] found that layering of RTIL on the silica is up to 20 nm after annealing based on X-ray reflectivity (XRR) results. In another high-energy XRR study, Mezger et al. [34] reported that RTILs in contact with a charged sapphire substrate show solid-like multilayer structure with at least seven molecular layers. Based on AFM topography results, Liu et al. [35], Bovio et al. [36] and Yokota et al. [37] reported that RTILs formed extended layering structure on the mica surface. By analyzing the AFM force-distance profile, Atkins et al. [2] concluded that there is an extended layering structure of RTILs on the mica surface. Using a surface force apparatus (SFA), Perkin et al. [32, 38, 39] also found the extended layering structure of RTILs at the RTIL/mica interface. Based on high resolution X-ray interface scattering, Zhou et al. [42] reported that layering of RTILs extends 3.5 nm into the bulk liquid at the RTIL-mica interface. Recent simulation and computational results also indicated that RTILs form extended layering structure on the mica surface [40-42].

For conventional molecular liquids, the solid-like layering has also been reported; but the layering is usually limited, e.g., up to a few molecular layers [30, 31]. The layering of molecular liquids has been explained by that the translational entropy available to the liquid molecules under spatial confinement at the liquid-solid interface decreases to the point at which it becomes thermodynamically favorable for the liquid molecules to form ordered layering structure [31]. In the layering process, the size and geometry of the liquid molecules are the keys since these two factors impact the packing efficiency [30, 31]. For RTILs, the bulky and asymmetric cation/anions are expected to decrease the packing efficiency. However, layering of RTILs is much more extended, indicating the existence of alternative mechanisms. Since all of the above-mentioned ceramic surfaces, e.g., silica, alumina and mica, are believed to be negatively charged [2, 15, 32-42], it is generally accepted by the RTIL community that the electrostatic interactions at RTIL/solid interface is critical to the extended layering of RTILs [35, 38, 40, 43-46]. Moreover, it has been speculated that self-assembling of RTILs is another key contributor to the layering as well [4]. Since RTIL ions, especially cations (Fig. 3), have a structure similar to the surfactant; the selforganization to form separate polar and non-polar domains is expected. Indeed, in bulk RTILs, there have been experimental, e.g., X-ray diffraction [47], and computational [48, 49] studies showing the existence of mesoscopic nanostructures, which indicates the self-assembling capability of RTILs. For RTIL at the RTIL/solid interface, Perkin et al. [39] proposed that RTILs form the layers composed of alternating polar and nonpolar domains based on SFA studies.

The electrostatic interaction and the self-assembling mechanisms are certainly reasonable though it is unclear how the solid surface is charged and how the structure of RTILs impacts the selfassembly. However, experimental results are not always consistent [50-52]. As shown in Fig. 4, our group [51] reported that, beyond one monolayer, droplets formed for RTILs on the silica surface based on angle-resolved X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (ARXPS) and AFM studies. Baldelli [52] recently reviewed a series of sum-frequency generation (SFG) spectroscopy studies and concluded that there is only monolayer, instead of multilayer, of RTILs on the charged solid surfaces. Given the fact that many different RTILs have been utilized in previous studies, the different wettability of RTILs, i.e., droplets vs. multilayer, could be attributed to the different chemical structure of RTILs. However, Deyko et al. [50] recently reported that complete dewetting of a RTIL, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide (BMIM NTf2), occurs on a clean mica surface under ultra-high vacuum, and no layering structure was observed at all. It is worthy of mentioning that the RTIL studied in this work [50] is exactly the same as in Ref. [36] where the extended layering was reported on the mica surface. Clearly, the dramatic difference cannot be attributed to the different chemistry of RTILs, indicating the existence of unknown mechanisms governing the layering and nanoscale wettability of RTILs on the mica and likely other ceramic surfaces.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (A) (a)-(f), AFM topography images of ultrathin RTILs on a silica substrate with a thickness of 0.5 molecular layer (ML), 0.6 ML, 0.8 ML, 0.9 ML, 1.1 ML, and 1.3 ML, respectively. (B) AR-XPS results of ultrathin RTIL films on a silica substrate. (C) Schematic showing the molecular arrangement of DMPIIm on a silica substrate (not to scale). Reproduced with permission [51]. Copyright 2013, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

As shown in Fig. 5, bulk mica has layered structure with K+ staying between the AlSiO layers, keeping the charge neutral. After the mica is cleaved to produce two surfaces, half of the K+ go with the top surface and the other half go with the bottom surface, still keeping the surface charge neutral [53-56]. Though it is generally believed that the mica surface carries negative charges [2, 53-56], this is true only when the surface K+ is dissolved in an effective solvent, i.e., with high dielectric constant such as water whose dielectric constant is 80.4 [57], and leaves the mica surface. However, almost all RTILs studied previously [2, 12, 22-32] have a dielectric constant lower than 15 [3, 58, 59] and the solvating power of RTILs is close to conventional aprotic solvent, e.g., dichloromethane and methylamine; but not as high as water [58]. This idea is further supported by the fact that many inorganic salts are not soluble in RTILs [3, 52]. Therefore, RTILs themselves should not dissolve the surface K+ and induce the surface charging of mica in the first place. One possible explanation for previously reported layering is the surface-adsorbed water. It is well known that the mica surface adsorbs water up to ~0.4 nm even under ambient conditions [60-63]. If there is water on the mica surface, K+ ions will be dissolved and thus the mica surface will carry negative charges.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Schematic of the surface charging mechanism of mica [53-56]. Reproduced with permission [63]. Copyright 2009, American Chemical Society. | |

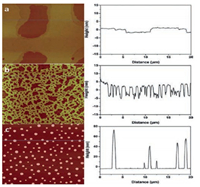

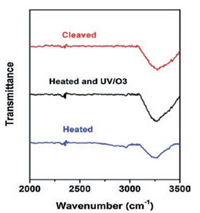

Recent research in our lab [64] suggested that, adsorbed water on the mica surface is the key to the extended layering of RTILs. The AFM and ATR-FTIR results showed that RTILs form extended layering when water is adsorbed on the mica surface under ambient conditions. However, when the water is removed by heating at elevated temperatures, instead of layering, RTILs exhibit droplet structure, i.e., dewetting [64]. A commonly used RTIL, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tris (pentafluoroethyl) trifluorophosphate (BMIM-FAP), was applied on atomically smooth mica by dip-coating based on a procedure established in our lab [51, 64, 65]. To uncover the nano-scale wettability experimentally, we "visualized" the nano-scale contact angle with AFM. If the nanometer-thick RTIL wets the mica surface completely, RTIL nanofilms are observed, i.e., the contact angle is 0°. Otherwise, nano-sized RTIL droplets will show up in the AFM image. For the sample fabricated with freshly cleaved mica under ambient conditions (22 ℃, RH = 45%), the extended layering structure is clearly visible at the edge of the film as shown in Fig. 6. Indeed, the layering extends up to 17 nm [64]. These observations are consistent with previous reports [2, 15, 32-42] showing extended layering of RTILs on the mica surface. Interestingly, as also shown in Fig. 6, when the freshly cleaved mica was heated in a conventional oven at 120 ℃ for 1 h to remove water before dipcoating, the droplets were observed on the BMIM-FAP/mica sample and the solid-like layering completely disappeared! To confirm the water removal on the mica surface after heating at 120 ℃ for 1 hr, the mica surface was characterized by ATR-FTIR. As shown in Fig. 7, before heating, there is a broad peak between 3000 cm-1 and 3500 cm-1, which is attributed to the adsorbed water based on the previous literature [66]. After heating, the intensity of the "water" peak decreases significantly, indicating the (partial) removal of water by heating. Both AFM and FTIR results indicated that the water plays a decisive role in the RTIL layering. This also explains the previous controversy initiated by the observed "dewetting" behavior of RTILs on the mica surface under high vacuum [50]. Almost all of the previous experiments [2, 15, 32-42], on RTIL/mica were conducted under ambient conditions. Therefore, water adsorption on the mica surface is expected and that is why the extended layering of RTILs at the RTIL/mica interface has been frequently reported. For the only study [50] conducted in the high vacuum, there is no water adsorption and, therefore, complete dewetting was observed.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. (left) AFM images of BMIM-FAP (1 g/L solution) dip-coated on a freshly cleaved mica surface (a), mica heated for 5 min at 120 ℃ (b), and mica heated for 1 h at 120 ℃ (c). AFM images are 20 μm × 20 μm and height bar is 20 nm. (right) Corresponding line profiles. Reproduced with permission [64]. Copyright 2015, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. ATR-FTIR of freshly cleaved mica (red), heat-treated (1 h at 120 ℃) mica (blue), and heat-treated mica with UV/O3 treatment (black). Reproduced with permission [64]. Copyright 2015, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

Our results showed that adsorbed water on the mica is the key to the RTIL layering. Why does adsorbed water promotes the RTIL layering? There are two possible mechanisms as schematically shown in Fig. 8: (1) Water-enabled surface charging. Since RTILs have low dielectric constants [3, 58, 59], they cannot effectively dissolve K+ ions on the mica and induce the surface charging. Only when there is adsorbed water, which is an effective solvent, on the mica surface, K+ ions will be dissolved and leave the mica surface and thus the surface will carry negative charges. As a result, the cations of the RTIL are able to occupy the "empty" site left by K+, initiating the extended layering cations/anions. Since the size of hydrated K+ is about the same as the BMIM cation [67], the hydrated K+ could easily fits itself into the RTILs near the interface. (2) Water-assisted self-assembling: In bulk RTILs, it has been reported that the water induces the stronger self-assembling of RTILs. Jiang et al. [68] conducted molecular dynamics simulation and found that addition of water into RTILs results in more organized nanostructure, with separate polar and nonpolar domains. They concluded that water is coupled with RTILs ions via H-bonding and leads to a more extended polar network that enhances the segregation of polar and non-polar domains. Firestone et al. [69] reported that water addition into a RTIL, 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide, results in the formation of a liquid-crystalline gel with lamellar structure based on X-ray scattering study. They also attributed the enhanced self-assembly within RTILs to the formation of water-ion network via H-bonding. The similar effect of water could occur at the RTIL/solid interface as well. Because the solid surface serves as a flat template to initiate the packing of RTILs, the water-assisted self-assembling of RTIL is expected to result in the extended layering structure. Since previous research [34, 39, 51] suggested the alternative cation/ anion layering of RTILs on the ceramic surface, e.g., silica, mica and alumina, the water-anion (or water-cation) H-bonding will reduce the anion-anion (or cation-cation) repulsion within the same layer and thus stabilize the layered structure.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 8. Schematic of the effect of adsorbed water on the layering of RTIL on the mica surface. | |

Our idea is echoed by recent works of Cheng et al. [67, 70]. Based on AFM force-distance profile, they concluded that addition of water into RTILs, instead of on the mica, promotes the layering of the RTIL on the mica surface and attributed the enhanced layering to the water-enabled surface charging [67, 70]. More recently, using AFM force-distance analysis, Cui et al. [71] studied the layering of RTILs on the electrified gold surface and found that addition of water up to 30% improves the ordering of RTIL layers though further addition of water reduces the ordering. Cui et al. [71] attributed the improved ordering to the H-bonding between water and RTIL. Since the charge is applied by external voltage on the gold surface, the addition of water should not impact the surface charging. As a result, the finding here supports the idea of waterassisted self-assembling as described above (Fig. 8). However, there have been different voices. Jurado et al. [72] and Sakai et al. [73] reported that addition of water reduces the ordering of RTIL layers on mica based on their AFM force-distance analysis, respectively. McDonald et al. [74] utilized amplitude modulated atomic force microscopy (AM-AFM) to probe metal ion adsorption at the RTIL/mica interface and concluded that solvation of K+ occurs when mica is in contact with dry RTIL. The reasons for the inconsistency of the different research groups remain unclear. In addition to different chemistry of RTILs used by different research groups, it is worthy noting that the amount of adsorbed water on the mica surface (under ambient) has not been well controlled. Since the humidity could change significantly when the mica is cleaved from lab to lab, this parameter requires more careful control.

Since graphite surface has no charge, there is no electrostatic attraction at the RTIL/graphite interface, which is expected to reduce the solid-like layering of RTILs. Indeed, Bovio et al. [36] reported that BMIM NTf2 forms nanodroplets, instead of uniform nanofilms, on the highly ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) surface (Fig. 9a). However, as shown in Fig. 9b, Atkin and Warr [75] conducted the AFM force-distance analysis and found that, on the graphite surface, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate (EMIM ACE) can form seven solid-like molecular layers. The dramatic difference between the two can certainly be related to the different RTILs utilized in two studies. However, another important parameter is the roughness. It has been long recognized that the solid-like layering of liquids occurs only when the solid surface is atomically smooth [30]. Though HOPG is thought to be atomically smooth and used to calibrate AFM, it has step edges (Fig. 9a). As a result, HOPG is only atomically smooth locally, i.e., within in area with no step edges; but not globally. As a result, when the dilute solution of RTILs are casted on the HOPG, nanodroplets are formed and captured by AFM topography [36]. In AFM force-distance analysis, since the AFM tip is very sharp and detects the RTIL/ graphite interface locally, the layering is still detected.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 9. (a) AFM topographies of thin BMIM NTf2 coatings on HOPG (Scale bar 1 μm). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [36]. Copyright 2009, American Chemical Society. (b) Force versus distance profile for an AFM tip approaching and retracting from a graphite surface in EMIM ACE. Reproduced with permission [75]. Copyright 2007, American Chemical Society. | |

Interestingly, Atkin and Warr [75] also reported that EMIM ACE has only three solvation layers on the mica surface while the same RTIL has seven solvation layers on graphite. Since graphite surface has no charge, Coulombic force cannot be responsible for the extensive solid-like layers of EMIM ACE and there must be alternative mechanisms. Combining high resolution X-ray reflectivity (XRR) and fully atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, Zhou et al. [42] found that, on the graphene surface, the layering of BMIM NTf2 extends 2 nm into the bulk solution. Their [42] and a few other [76-79] MD studies indicated that imidazolium rings of the cation lie parallel to the graphitic surface. Based on this, Zhou et al. proposed that π-π+ stacking between the imidazolium ring and graphene is the key factor enabling the layering of RTILs on the graphene.

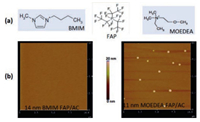

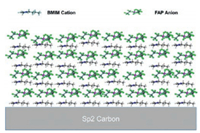

Recent experimental data [65] in our lab suggested that π-π+ stacking between the delocalized π electron of aromatic RTIL cation and the graphitic (sp2) carbon induces the solid-like layering of RTILs and therefore enhanced the wettability of nanometerthick RTILs significantly. To uncover the nano-scale wettability experimentally, we fabricated the nanometer-thick RTILs on the graphitic carbon substrate and then "visualized" the nano-scale contact angle with AFM [65]. If the nanometer-thick RTIL wets the carbon surface completely, a uniform RTIL nanofilm is observed, i.e., the contact angle is 0°. Otherwise, nano-sized RTIL droplets will show up in the AFM image. The two RTILs studied are 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tris(pentafluoroethyl) trifluorophosphate (BMIM FAP) and ethyldimethyl-(2-methoxyethyl) ammonium tris(pentafluoroethyl) trifluorophosphate (MOEDEA FAP), representing the cation with aromatic and aliphatic structure, respectively, as shown in Fig. 10a. The atomically smooth amorphous carbon (AC), with 70% sp2 carbon and 30% sp3 carbon, is utilized as the carbon substrate. The RTIL nanofilms were dip-coated on the AC substrate and the average film thickness was determined by ellipsometry measurement [51]. The average thickness of BMIMFAP and MOEDEA-FAP is 14 nm and 11 nm, respectively. As shown in Fig. 10b, AFM topography results indicate that BMIM FAP forms a uniform nanofilm on the amorphous carbon, i.e., complete wetting with a contact angle of 0°. For MOEDEA-FAP where aromatic imidazolium ring in BMIM is replaced by an aliphatic ammonium (Fig. 10a), the nano-sized droplet is clearly visible in the AFM topography image of MOEDEA-FAP on the amorphous carbon, indicating that partial wetting occurs.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 10. (a) Chemical structure of RTILs. (b) AFM topography images of BMIM-FAP and MOEDEA-FAP on the amorphous carbon. Reproduced with permission [19]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. | |

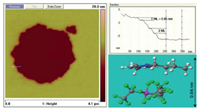

To uncover the underlying mechanism of nano-scale wettability, the molecular-level arrangement of BMIM-FAP in the nanofilms confined to the amorphous carbon was characterized by a "crosssection" AFM experiment. The 14 nm BMIM FAP/AC sample was punctured gently with a sharp needle and then the topography of the created hole was characterized by AFM. As shown in Fig. 11, along the inner wall of the hole, well-defined steps are clearly visible, indicating the layering structure. The step height is either one molecular layer (ML) or two MLs, matching the estimated ML thickness very well. (The ML thickness is estimated to be 0.84 nm for BMIM FAP based on previous report [51] and AFM results showed that ML step height is 0.85 nm.) The AFM results indicate that the solid-like layers of BMIM FAP on amorphous carbon are up to at least 17 molecular diameters. Our results are consistent with Ref. [75] and both studies suggest that there are extensive solidlike layers of RTILs on graphitic surfaces. This solid-like layering could explain the complete wetting of nanometer-thick BMIM-FAP on the graphitic surface.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 11. Ten nanometer BMIM FAP on AC with a "hole" and "cross-section" AFM profile of BMIM FAP/AC. Reproduced with permission [65]. Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society. | |

Then why does not the extensive solid-like layering occur to MOEDEA FAP? Interestingly, In the previous report [75] showing the solid-like layers of RTILs on HOPG, the RTIL used, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate (EMIM ACE), has different anion but also contains imidazolium ring in the cation. It has also been reported that single-walled carbon nanotubes form "bulky gels" when they are mixed with imidazolium-containing RTILs and it was proposed that the π-π+ stacking between the imidazolium ring and the sp2 carbon in the nanotubes initiates the ordered longrange packing of RTIL molecules [80]. In the imidazoliumcation, the positive charge is delocalized (π+) [81].When the imidazoliumcation is in contact with graphitic surface containing sp2 carbon (π electron), e.g., HOPG or amorphous carbon, π-π+ interaction could occur at the interface. The π-π+ interaction originates from both electrostatic and non-electrostatic interaction and the exact nature is still a matter of investigation [81]. However, previous studies [77, 81] suggested that, If the π-π+ interaction occurs between sp2π electron and the imidazolium ring, the imidazolium ring should take a parallel orientation to the graphitic substrate, e.g., π-π+ stacking, since the imidazolium ring is a delocalized π system. As a result, RTIL cations form a highly ordered "lamella-like" structure on the graphitic surface. In other words, the graphitic surface serves as a template to orient the imidazolium ring in an ordered parallel geometry, which does not exist in the bulk liquid. This parallel geometry initiates the extensive solid-like layering and the strong coulombic force between anions and cations of RTILs further promotes the growth of the lamella-like structure, as schematically shown in Fig. 12. For MOEDEA FAP, since it does not contain aromatic rings in the cation, π-π+ stacking is impossible and thus the extensivesolid-like layering does not occur. As a result, MOEDEA FAP forms nano-sized droplets on the amorphous carbon. More recently, Mahurin et al. [82] studied RTIL-graphene interaction with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy and also concluded that π-π+ stacking between imidazolium ring of the cation and the sp2 carbon promotes the layering of RTIL at the liquid/solid interface.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 12. Hypothesized "lamella-like" structure of solid-like layers in BMIM FAP confined to amorphous carbon (AC) (Not to scale). Reproduced with permission [65]. Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society. | |

Although the research on the wettability of nanometer-thick RTILs on solid surfaces is still in its infant stage, the progress and its implications in various applications are exciting. Moving forward, there are still many key questions to be addressed. First, what is the underlying mechanisms governing the macroscopic wettability of RTILs? In other words, will the existing models for molecular liquids be appropriate to describe the wetting behavior of RTILs. To answer this question, a systematic research involving RTILs with different chemical structure of cations and anions, using existing models, e.g., Fowkes [83], Owens-Wendt [84], and Neumannm [85] models, will be a good start. Equally important, the wettability of RTILs on various solids, ranging from low-energy ones like Teflon to high-energy ones like mica, needs to be studied to uncover how the ionic nature of RTILs impacts the wettability. Second, for the wettability of nanometer-thick RTILs on the ceramic surfaces, e.g., mica, it is essential to fully understand the charging mechanism of solids in contact with RTILs since it has been generally accepted that the electrostatic force at the RTIL/solid interface is critical to the nanoscale wetting. To this end, it is highly desirable to directlycharacterize the surface charging of the solid in contact with liquids, e.g., RTILs and water. Moreover, investigation of RTILs with different solvation efficiency will greatly help us to uncover the charging mechanism of the ceramics. The self-assembling of RTILs in bulk have been extensively studied and the existence of nanostructure has been reported by many research groups [4]. While charged ceramic surfaces serve as a flat template, the selfassembling promotes the layering and increases the wettability of nanometer-thick films. What is the role of water in selfassembling? This question is important since water adsorption is inevitable in practical application. Moreover, it will be interesting to extend the research from RTIL/water to RTIL/solvent mixture since the latter is believed to provide better performance in many applciations [86]. The learning here is also relevant to the RTIL/metal interface where the charging is enabled by an externally applied voltage. Third, to uncover the governing mechanisms of wetting behavior of nanometer-thick RTILs on the graphitic carbon surface, it is critical to experimentally testify the existence of π-π+ interaction between RTIL and graphitic surface using spectroscopy. Moreover, it is desirable to separate the effect of spatial confinement and π-π+ interaction, which could be achieved by careful selection of RTILs and solids. Another interesting question is whether the wetting behavior of nanosized RTILs inside the nanoporous solid is the same as on the flat solid. It is unknown at this point whether the curvature of the pores and stronger spatial confinement will change the wetting behavior. Last but not least, how fast (or slow) is the wetting process when the nanometer-thick RTIL wets the solid surface completely? There has been very limited research on this. Since the kinetics of wetting is important in real-life application such as lubrication and catalysis, the breakthrough on understanding the mechanisms governing the kinetics will facilitate the application of RTILs greatly.

AcknowledgmentL. Li acknowledges the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (ACS PRF No. 54840-DNI5), Advanced Storage Technology Consortium (ASTC) and Taiho Kogyo Tribology Research Foundation (TTRF) for the financial support. X. Gong acknowledges the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21774098).

| [1] |

T. Welton, Chem. Rev. 99(1999) 2071-2084. DOI:10.1021/cr980032t |

| [2] |

R. Hayes, G.G. Warr, R. Atkin, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12(2010) 1709-1723. DOI:10.1039/b920393a |

| [3] |

M.V. Fedorov, A.A. Kornyshev, Chem. Rev. 114(2014) 2978-3036. DOI:10.1021/cr400374x |

| [4] |

R. Hayes, G.G. Warr, R. Atkin, Chem. Rev. 115(2015) 6357-6426. DOI:10.1021/cr500411q |

| [5] |

F. Zhou, Y. Liang, W. Liu, Chem. Soc. Rev. 38(2009) 2590-2599. DOI:10.1039/b817899m |

| [6] |

J. Le Bideau, L. Viau, A. Vioux, Chem. Ionogels Soc. Rev. 40(2011) 907-925. DOI:10.1039/C0CS00059K |

| [7] |

M. Armand, F. Endres, D.R. MacFarlane, H. Ohno, B. Scrosati, Nat. Mater. 8(2009) 621-629. DOI:10.1038/nmat2448 |

| [8] |

E. Yoo, J. Kim, E. Hosono, et al., Nano Lett. 8(2008) 2277-2282. DOI:10.1021/nl800957b |

| [9] |

P.G. Bruce, B. Scrosati, J.M. Tarascon, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47(2008) 2930-2946. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1521-3773 |

| [10] |

F. Endres, O. Höfft, N. Borisenko, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12(2010) 1724-1732. DOI:10.1039/b923527m |

| [11] |

H. Liu, Y. Liu, J. Li, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12(2010) 1685-1697. DOI:10.1039/b921469k |

| [12] |

E.B. Fox, A.E. Visser, N.J. Bridges, J.W. Amoroso, Energy Fuels 27(2013) 3385-3393. DOI:10.1021/ef4002617 |

| [13] |

J.M.P. França, S.I.C. Vieira, M.J.V. Lourenço, S.M.S. Murshed, C.A. Nieto de Castro, J. Chem. Eng. Data 58(2013) 467-476. DOI:10.1021/je301183r |

| [14] |

P. Keblinski, S.R. Phillpot, S.U.S. Choi, J.A. Eastman, J. Int. Heat Mass Transfer 45(2002) 855-863. DOI:10.1016/S0017-9310(01)00175-2 |

| [15] |

H. Li, R.J. Wood, M.W. Rutland, R. Atkin, Chem. Commun. 50(2014) 4368-4370. DOI:10.1039/c4cc00979g |

| [16] |

W. Shi, D.C. Sorescu, J. Phys. Chem. B 114(2010) 15029-15041. DOI:10.1021/jp106500p |

| [17] |

A. Erto, A. Silvestre-Albero, J. Silvestre-Albero, et al., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 448(2015) 41-50. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2015.01.089 |

| [18] |

P. Simon, Y. Gogotsi, Acc. Chem. Res. 46(2012) 1094-1103. |

| [19] |

X. Gong, B. West, A. Taylor, L. Li, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55(2016) 6391-6397. DOI:10.1021/acs.iecr.6b00822 |

| [20] |

P.H. Kasai, Tribol. Lett. 13(2002) 155-166. DOI:10.1023/A:1020101007436 |

| [21] |

B. Ramos-Alvarado, S. Kumar, G.P. Peterson, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7(2016) 3497-3501. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b01605 |

| [22] |

N.J. Bridges, A.E. Visser, E.B. Fox, Energy Fuels 25(2011) 4862-4864. DOI:10.1021/ef2012084 |

| [23] |

K.B. Sidhpuria, A.L. Daniel-da-Silva, T. Trindade, J.A.P. Coutinho, Green Chem. 13(2011) 340-349. DOI:10.1039/c0gc00690d |

| [24] |

T. Young, Philos. Trans.R. Soc. London 95(1805) 65-87. DOI:10.1098/rstl.1805.0005 |

| [25] |

R. Hayes, G.G. Warr, R. Atkin, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12(2010) 1709-1723. DOI:10.1039/b920393a |

| [26] |

R. Sedev, Curr. Opin. Colloid Interf. Sci. 16(2011) 310-316. DOI:10.1016/j.cocis.2011.01.011 |

| [27] |

I. Delcheva, J. Ralston, D.A. Beattie, M. Krasowska, Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 222(2015) 162-171. DOI:10.1016/j.cis.2014.07.003 |

| [28] |

L. Gao, T.J. McCarthy, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129(2007) 3804-3805. DOI:10.1021/ja070169d |

| [29] |

A.M. Cione, O.A. Mazyar, B.D. Booth, C. McCabe, G.K. Jennings, J. Phys. Chem. C 113(2009) 2384-2392. DOI:10.1021/jp808098w |

| [30] |

J. N. Israelachvili, Intermolecular and Surface Forces Revised Third Edition, Academic Press, 2011.

|

| [31] |

S. Granick, Science 253(1991) 1374-1379. DOI:10.1126/science.253.5026.1374 |

| [32] |

S. Perkin, T. Albrecht, J. Klein, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12(2010) 1243-1247. DOI:10.1039/B920571C |

| [33] |

A.J. Carmichael, C. Hardacre, J.D. Holbrey, M. Nieuwenhuyzen, K.R. Seddon, Mol. Phys. 99(2001) 795-800. DOI:10.1080/00268970010012301 |

| [34] |

M. Mezger, H. Schröder, H. Reichert, et al., Science 322(2008) 424-428. DOI:10.1126/science.1164502 |

| [35] |

Y. Liu, Y. Zhang, G. Wu, J. Hu, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128(2006) 7456-7457. DOI:10.1021/ja062685u |

| [36] |

S. Bovio, A. Podesta, C. Lenardi, P. Milani, J. Phys. Chem. B 113(2009) 6600-6603. DOI:10.1021/jp9022234 |

| [37] |

Y. Yokota, T. Harada, K.-i. Fukui, Chem. Commun. 46(2010) 8627-8629. DOI:10.1039/c0cc02643c |

| [38] |

S. Perkin, L. Crowhurst, H. Niedermeyer, et al., Chem. Commun. 47(2011) 6572-6574. DOI:10.1039/c1cc11322d |

| [39] |

S. Perkin, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14(2012) 5052-5062. DOI:10.1039/c2cp23814d |

| [40] |

D. Dragoni, N. Manini, P. Ballone, Chemphyschem 13(2012) 1772-1780. DOI:10.1002/cphc.201100947 |

| [41] |

R.S. Payal, S. Balasubramanian, J. Phys.:Condens. Matter 26(2014) 284101. DOI:10.1088/0953-8984/26/28/284101 |

| [42] |

H. Zhou, M. Rouha, G. Feng, et al., ACS nano 6(2012) 9818-9827. DOI:10.1021/nn303355b |

| [43] |

S. Perkin, M. Salanne, P. Madden, R. Lynden-Bell, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110(2013) E4121. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1314188110 |

| [44] |

H. Zhou, M. Rouha, G. Feng, et al., Acs Nano 6(2012) 9818-9827. DOI:10.1021/nn303355b |

| [45] |

I. Bou-Malham, L. Bureau, Soft Matter 6(2010) 4062-4065. DOI:10.1039/c0sm00377h |

| [46] |

A.M. Smith, K.R.J. Lovelock, N.N. Gosvami, et al., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4(2013) 378-382. DOI:10.1021/jz301965d |

| [47] |

A. Triolo, O. Russina, H.-J. Bleif, E. Di Cola, J. Phys. Chem. B 111(2007) 4641-4644. DOI:10.1021/jp067705t |

| [48] |

Y. Wang, G.A. Voth, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127(2005) 12192-12193. DOI:10.1021/ja053796g |

| [49] |

S.M. Urahata, M.C.C. Ribeiro, J. Chem.Phys. 120(2004) 1855-1863. DOI:10.1063/1.1635356 |

| [50] |

A. Deyko, T. Cremer, F. Rietzler, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 117(2013) 5101-5111. DOI:10.1021/jp3115397 |

| [51] |

X. Gong, S. Frankert, Y. Wang, L. Li, Chem. Commun. 49(2013) 7803-7805. DOI:10.1039/c3cc43392g |

| [52] |

S. Baldelli, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4(2012) 244-252. |

| [53] |

T. Cheng, H. Sun, J. Phys. Chem. C 116(2012) 16436-16446. DOI:10.1021/jp3020595 |

| [54] |

H. Sakuma, T. Kondo, H. Nakao, K. Shiraki, K. Kawamura, J. Phys. Chem. C 115(2011) 15959-15964. DOI:10.1021/jp111936s |

| [55] |

R.M. Pashley, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 83(1981) 531-546. DOI:10.1016/0021-9797(81)90348-9 |

| [56] |

L. Cheng, P. Fenter, K.L. Nagy, M.L. Schlegel, N.C. Sturchio, Phys. Rev. Lett. 87(2001) 156103. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.156103 |

| [57] |

X. Gong, V. Vahdat, S. Frankert, Tribol. Trans. 58(2015) 679-685. DOI:10.1080/10402004.2014.1003120 |

| [58] |

L.E. Barrosse-Antle, A.M. Bond, R.G. Compton, et al., Chem. Asian J. 5(2010) 202-230. DOI:10.1002/asia.v5:2 |

| [59] |

J.P. Hallett, T. Welton, Chem. Rev. 111(2011) 3508-3576. DOI:10.1021/cr1003248 |

| [60] |

K. Xu, P.G. Cao, J.R. Heath, Science 329(2010) 1188-1191. DOI:10.1126/science.1192907 |

| [61] |

G.J. Leggett, M.C. Davies, D.E. Jackson, J. Phys. Chem. 97(1993) 8852-8854. DOI:10.1021/j100137a006 |

| [62] |

F. Forouzan, A.J. Bard, J. Phys. Chem. B 101(1997) 10876-10879. DOI:10.1021/jp972728g |

| [63] |

A. Malani, K.G. Ayappa, J. Phys. Chem. B 113(2009) 1058-1067. DOI:10.1021/jp805730p |

| [64] |

X. Gong, A. Kozbial, L. Li, Chem. Sci. 6(2015) 3478-3482. DOI:10.1039/C5SC00832H |

| [65] |

X. Gong, A. Kozbial, F. Rose, L. Li, ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 7(2015) 7078-7081. DOI:10.1021/acsami.5b01140 |

| [66] |

J.M. Roscoe, J.P.D. Abbatt, J. Phys. Chem. A 109(2005) 9028-9034. DOI:10.1021/jp050766r |

| [67] |

H.W. Cheng, P. Stock, B. Moeremans, et al., Adva. Mater. Interf. 2(2015) 1500159. DOI:10.1002/admi.201500159 |

| [68] |

W. Jiang, Y. Wang, G.A. Voth, J. Phys. Chem. B 111(2007) 4812-4818. DOI:10.1021/jp067142l |

| [69] |

M.A. Firestone, J.A. Dzielawa, P. Zapol, et al., Langmuir 18(2002) 7258-7260. DOI:10.1021/la0259499 |

| [70] |

H.W. Cheng, J.N. Dienemann, P. Stock, Sci. Rep. 6(2016) 30058. DOI:10.1038/srep30058 |

| [71] |

T. Cui, A. Lahiri, T. Carstens, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 120(2016) 9341-9349. |

| [72] |

L.A. Jurado, H. Kim, A. Rossi, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18(2016) 22719-22730. DOI:10.1039/C6CP03777A |

| [73] |

K. Sakai, K. Okada, A. Uka, et al., Langmuir 31(2015) 6085-6091. DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b01184 |

| [74] |

S. McDonald, A. Elbourne, G.G. Warr, R. Atkin, Nanoscale 8(2016) 906-914. DOI:10.1039/C5NR05833C |

| [75] |

R. Atkin, G.G. Warr, J. Phys. Chem. C 111(2007) 5162-5168. |

| [76] |

S.A. Kislenko, I.S. Samoylov, R.H. Amirov, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 11(2009) 5584-5590. DOI:10.1039/b823189c |

| [77] |

R. Singh, J. Monk, F.R. Hung, J. Phys. Chem. C 114(2010) 15478-15485. DOI:10.1021/jp1058534 |

| [78] |

S. Wang, S. Li, Z. Cao, T. Yan, J. Phys. Chem. C 114(2009) 990-995. |

| [79] |

J. Vatamanu, O. Borodin, G.D. Smith, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132(2010) 14825-14833. DOI:10.1021/ja104273r |

| [80] |

T. Fukushima, A. Kosaka, Y. Ishimura, et al., Science 300(2003) 2072-2074. DOI:10.1126/science.1082289 |

| [81] |

J.C. Ma, D.A. Dougherty, Chem. Rev. 97(1997) 1303-1324. DOI:10.1021/cr9603744 |

| [82] |

S.M. Mahurin, S.P. Surwade, M. Crespo, S. Dai, J. Raman Spectrosc.(2015). |

| [83] |

F.M. Fowkes, J. Phys. Chem. 67(1963) 2538-2541. DOI:10.1021/j100806a008 |

| [84] |

D.K. Owens, R. Wendt, J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 13(1969) 1741-1747. DOI:10.1002/app.1969.070130815 |

| [85] |

D. Li, A. Neumann, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 148(1992) 190-200. DOI:10.1016/0021-9797(92)90127-8 |

| [86] |

S.W. Coles, A.M. Smith, M.V. Fedorov, F. Hausen, S. Perkin, Faraday Discuss(2017). DOI:10.1039/C7FD00168A |

2017, Vol. 28

2017, Vol. 28