b New Energy Materials and Technology Laboratory, Department of Applied Chemistry, College of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China

Lithium manganese oxide (LMO) spinel has been considered as one of the most promising cathode materials for large power batteries and energy-storage systems in recent years. It exhibits good electrochemical performance and high safety at high current rate. Manganese is one of the most abundant elements in the Earth crust, and it is environmentally benign. However, this LMO material shows a significant capacity fading during long-term electrochemical cycling, particularly at elevated temperatures (55 ℃), mainly because of the following possible reasons: (1) the structural collapse due to Jahn-Teller distortion in the charge and discharge process, (2) enhanced manganese ion dissolution into the electrolyte, (3) the thermal decomposition of LiPF6-based carbonate electrolytes [1-5].

A large number of efforts are carried out to resolve the above issues. First of all, synthesis methods are studied. The traditional methods mainly include solid state method and soft chemical method. For solid state method, repeated grinding and high temperature reaction for a long time are always needed to form spinel crystal. Soft chemical methods include Pechini method, solgel method, hydrothermal method and co-precipitation method etc. [6-12]. In these methods, the precursors are obtained from liquid solution, so all the components can be distributed very homogeneously at atomic-molecular level in these precursors. Soft chemical synthesis can be performed at comparatively low temperatures and within short periods. Solid state method is an easy preparation process, the obtained product shows high bulk density but poor electrochemical performance. In the synthesis process, some undesirable impure phases can be formed in the product because of the long-range diffusion of atoms. The product synthesized by soft chemical method shows good electrochemical performance but low density, and it is a complex process. In recent years, some new method are put forward such as solid-state combustion method [13], electrospinning method [14], spray pyrolysis method [15], solution combustion method [16] and mechanical alloying method [17].

Secondly, modified methods are adopted to improve the performance of LMO spinel including doping and coating. The investigated doping ions include cations and anions, the cationic doping elements mainly include Li, Mg, Ni, Zn, Cu, Al, Cr, Co, Ga, Gd, La, Ce, Nd, Sm, Tb, Sr, Dy, Mo, B, Fe, Ti, Sn [18-30], Er, Sc, Y [2] etc., while the reported anions mainly consist of F- [31], Cl-, Br- [2], S2- [32], BO33-, PO43-, SiO32- [33, 34] etc. Sometimes, single ion doping cannot reach satisfactory effect, dual or multiple ions doping simultaneously have also been developed. Surface coating is an effective approach in which an artificial protective layer is used to prevent Mn ions from contacting with electrolyte, and restrain the Mn dissolution. The coating materials mainly include various oxides, fluorides, phosphates, lithium compounds, carbon materials, and polymers [2, 35].

Besides doping and coating, some new techniques are developed in LMO spinel such as controlling the nanoparticles granularity and spheroidizing of particles [2, 13, 16, 36]. Although a certain progress has been made in these researches, LMO spinel has not been put into large-scale commercial applications. The properties of LMO spinel need to be further improved.

In terms of choice for doping elements, few researchers select +5 valence cations. Hernan et al. investigated the electrochemical properties of vanadium doped LMO spinel in different voltage window [37]. The results show that it has a discharge capacity of 105 Ah kg-1 within the range of 4.6-2.5 V. Herein, we synthesized a spherical Li-rich LMO spinel cathode material doped with +5 valence niobium ion and phosphate by an ion implanted method. The morphology of the prepared material is obtained by controlling the morphology of the manganese dioxide precursors. The properties of the material and synthesis mechanism were also investigated in detail in this work.

2. Results and discussion 2.1. XRD analysis on the raw materials, MnO2 precursor, SP and IPFigs. 1 and S1 (Supporting information) are the XRD patterns of the precursor mixtures prepared by different method and the raw material lithium hydroxide monohydrate and manganese dioxide precursor. Fig. S1a (Supporting information) suggests that the lithium hydroxide monohydrate is regular crystal structure with high crystallinity, while the precursor MnO2 indicate a γ-MnO2 structure (JCPDS card No. 30-820) with low crystallinity as shown in Fig. S1b (Supporting information) [36, 38].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. XRD patterns of the mixture SP and IP. | |

Fig. 1 shows that the XRD patterns of SP comprise the patters of lithium hydroxide monohydrate and manganese dioxide. The characteristic peaks of lithium hydroxide monohydrate and manganese dioxide both appear on the diffraction pattern of SP. It demonstrates that the lithium hydroxide monohydrate and the manganese dioxide were just simply blended in physical form. However, the characteristic peaks of the lithium hydroxide monohydrate disappear in the XRD patterns of IP. It implies that lithium hydroxide monohydrate has been dissolved.

2.2. Thermal analysisTo further investigate the component of the mixture and synthesis process, TG/DSC is carried out from room temperature to 900 ℃. Fig. 2(a) is the TG-DSC curve of the pure lithium hydroxide monohydrate. A dehydration process can be found at 100 ℃ with a strong endothermic peak in DSC curve accompanied by a significant weight loss in TG curve. The solid lithium hydroxide transforms into liquid phase at 430-480 ℃ where there is a strong heat absorption phenomenon without weight change. Lithium hydroxide decompose at about 600 ℃ with weight loss. The whole thermal reaction process can be revealed by Eqs. (1)-(3):

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. TG/DSC of the raw materials LiOH·H2O (a), MnO2 precursor (b), mixtures SP (c) and IP (d). | |

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

In this experiment, 43.0% of weight loss is observed, and it is extremely close to the theoretical weight loss value of 42.8% calculated from Eqs. (1)-(3).

Fig. 2(b) is the curve of manganese dioxide precursor. The results show that there is a small amount of heat absorption along with continuous weight change. It should be related with the adsorbed water removal from the manganese dioxide. It can be inferred that the endothermic decomposition of the manganese dioxide happened near 555 ℃ because of the apparent sharp endothermic peak with a straight line loss in weight. The reaction is as follows:

|

(4) |

Fig. 2(c) is the TG-DSC curve of the precursor SP obtained by the solid method. It can be found that there are five endothermic peaks corresponding to the dehydration of lithium hydroxide monohydrate, the melting of lithium hydroxide, the decomposition of lithium hydroxide, the decomposition of manganese dioxide and the forming of LMO spinel respectively at 100 ℃, 400 ℃, 500 ℃, 650 ℃, 830 ℃. It may exist the following reaction equations according to the raw material component of SP.

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

It is obvious that the endothermic peaks are consistent with that of the pure lithium hydroxide and manganese dioxide except the peak at 830 ℃, although some alterations to the temperature coordinates may be caused by the instrument. It also proves that SP is simply consisted of lithium hydroxide and manganese dioxide by physical mixing. The results are consistent with that of XRD analysis. The Eq. (9) is not so consistent with the TG curve at about 830 ℃, it indicates that the formation process of the LMO spinel is complex in the solid state method. The theoretical weight loss is 19.2% according to Eqs. (5)-(9), while the actual experimental result is 24.6%. It is reasonable because the manganese dioxide usually contains about 5 wt% water.

Fig. 2(d) is the TG-DSC curve of the precursor IP obtained by the ion implanted method. It shows that there are two endothermic peaks on the DSC curve at about 560 ℃ and 800 ℃ along with two significant weight change on TG curve. The two peaks are corresponding to the decomposition of manganese dioxide and the formation of LMO spinel. It can also be inferred that there is no lithium hydroxide in IP, because no peaks due to the dehydration of lithium hydroxide monohydrate and the melting of lithium hydroxide were found. The possible reaction mechanism is as follows, lithium hydroxide monohydrate is dissolved with the help of ethylene glycol or glycerol in the mixing process, when a large amount of heat is produced, and the lithium ions have been implanted into the pore of manganese dioxide under the action of the heat. Then the mixture is transformed into Li2O·4MnO2 compound after drying. So the forming process of LMO can be represented by Eq. (10).

|

(10) |

The actual experimental weight loss is 5.0%. It is close to the theoretical value of 4.2% according to Eq. (10).

2.3. The morphology analysisFig. 3(a) is the SEM image of the MnO2 precursor. It shows that the pristine submicron fibrous MnO2 particles were gathered into micrometer spherical secondary particles. A large number of pores were formed between the fibrous particles, which would provide good channels for the lithium ion injection in the ion implantation method. The spherical particle diameter is of about 10 μm.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. SEM images of MnO2 precursor (a) and as prepared LMO (b: SLM, c: LM, d: LLM, e: LLMN, f: LLMNP). | |

Fig. 3(b)-(f) are the SEM images of the prepared LMO. All the particles with spherical morphology were consisted of primary submicron crystalline grain with different size and shape. SLM is consisted of the octahedral and irregular tiny particles. It indicates that the material does not fully grow into octahedral particles during the high temperature reaction. The particles of LM and LLM are composed of octahedral grains with high crystallization, while those of LLMN and LLMNP are composed of grains with irregular shape and smooth surface. Besides, the octahedral crystal edges disappear in LLMN and LLMNP.

The results of Fig. 3 demonstrate that the synthesis method and doping have influence on the particle morphology of lithium manganese oxide spinel prepared. This effect will be further reflected from the microstructure and electrochemical performance.

2.4. XRD analysis of as prepared samplesFig. 4 is the XRD patterns of the prepared samples in the range of 2θ from 10-90°. The diffraction peaks of the samples can be well indexed to a cubic spinel structure with Fd-3 m space group, which is consistent with JCPDS Card No: 35-0782. The diffraction peak intensity of SLM is lower than that of the other samples. There are two weak diffraction peaks at ca. 32.5° and 55.3° for SLM which corresponds to the strongest characteristic diffraction peak of Mn2O3 (PDF 78-0390), indicating the presence of a trace amount of Mn2O3 impurity phase in this material [39]. It cannot be noticed any strange reflection in the patterns of LM, LLM, LLMN, LLMNP. The (220) peak cannot be found in the XRD patterns for all the five samples. It indicates that the tetrahedral sites (8a) are only occupied by lithium atoms.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. XRD patterns of LMO samples. | |

The ratios of the diffraction peak intensity due to different crystal planes and corresponding 2θ are showed in Table S1 (Supporting information). The ratios I(111)/I(311) of sample SLM, LM, LLM, LLMN, LLMNP are 2.68, 2.69, 2.87, 2.03, 2.15 and 2.53, 3.16, 2.53, 2.34, 2.24 for I(111)/I(400) respectively. The ratios of I(111)/I(311) and I(111)/I(400) for sample SLM, LM, LLM are larger than that of LLMN, LLMNP, it indicates that SLM, LM, LLM crystal particles grow well along the (111) crystal plane, so the particles exhibit an octahedral shape. The ratios of I(111)/I(311) and I(111)/I(400) for sample LLMN and LLMNP decrease, which implies that the crystal growth along the (311) and (400) surface is enhanced, while that along the (111) surface is restrained. So the crystalline grain presents arc shape with smooth surface without crystal edge. This result is consistent with the SEM results shown in Fig. 3.

The location and strength of the diffraction peaks and lattice parameters are also summarized in Table S1 (Supporting information). Afterlithium ions have replaced parts of themanganese ions in LLM, the lattice parameter decreases from 8.2417 Å(LM) to 8.2296 Å (LLM). The diffraction peaks are slightly shifted to larger angle as shown in Fig. S2a-c (Supporting information). It may be caused by the reason that the content of the Mn4+ is increased because of the replacement of the Mn with Li, while the radius of Mn4+ ion issmaller than that of Mn3+ ion [40]. The lattice parameter of LLMN (8.2363 Å) is increased compared to LLM, because Nb5+ radius is close to Mn3+, and the Mn3+ content is much increased after doping niobium. The lattice parameter of LLMNP (8.2394 Å) is increased compared to LLMN, for the radius of polyanion phosphoric acid root is larger than that of oxygen ionic. All in all, the lattice parameter is increased after doping with niobium and phosphate ions and the diffraction peaks move toward to smaller angle as shown in Fig. S2a-c (Supporting information).

2.5. The chemical composition analysisThe XPS was carried out to determine the average oxidation state of manganese. Fig. 5 represents the Mn 2p XPS spectra for as prepared samples, in comparison with those for MnO2 and Mn2O3. The Mn 2p3/2 peak of MnO2 isobservedat 642.6 eV and that of Mn2O3 at 641.6 eV. As shown in Fig. 5, the Mn 2p3/2 peaks of as prepared samples are observed between those of MnO2 and Mn2O3. The Mn 2p3/2 peak position of LLM, LLMN and LLMNP shifts toward higher binding energies, it indicates that the average oxidation state of manganese in the three samples is increased. The average Mn valence and the relative ratio of Mn3+ and Mn4+ are calculated based on the results of XPS and summarized in Table S2 (Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Mn 2p XPS spectra for LMO samples, in comparison with those for MnO2 and Mn2O3. | |

The contents of Li, Mn, Nb and P were measured using ICP-AES. The O content was calculated based on the ICP-AES data and the average Mn valence. The chemical composition of the as-prepared samples was shown inTable S2 (Supporting information). The actual chemical formulas are very close to the design formulas.

2.6. Electrochemical performance analysisFig. 6 is the initial charge and discharge curves of SLM, LM, LLM, LLMN and LLMNP at 0.2 ℃ (1 ℃ = 148 mA g-1) rate. The discharge specific capacities are 113 mAh g-1, 123 mAh g-1, 117 mAh g-1, 120 mAh g-1 and 119 mAh g-1 respectively. The specific discharge capacity of the sample synthesized by solid method is lower than that by the ion implantation method. This is mainly related to the different crystallization of the product prepared by the two methods. The sample synthesized by the solid method has a poor crystallization and contains impurities, while the samples synthesized by the ion implantation method have a good crystallization.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. Charge and discharge curves of sample (a)SLM, (b)LM, (c)LLM, (d)LLMN, (e) | |

Fig. 6 also shows that the doping has great influence on the capacity. In the process of charging and discharging, the occurred redox reaction is mainly: Mn3+ → Mn4+. Thus, the capacity is determined by Mn3+ content [41]. Compared with LM, excess lithium ions were doped in LLM, so that part of Mn3+ would become Mn4+ and the average manganese valence would rise from 3.530 to 3.640 as shown in Table S2 in Supporting information. The specific discharge capacity of LLM is 117 mAh g-1, while that of normal spinel LM is 123 mAh g-1. The specific discharge capacity of LLMN recovers to 120 mAh g-1 for the Mn3+ content is increased after doping with pentavalent niobium ion. When doping phosphoric acid root, Mn3+ concentration is slightly decreased, thus the discharge capacity of LLMNP is declined to 119 mAh g-1.

The two voltage plateaus in 4 V region are obvious in sample SLM and LM, but not so evident in sample LLM. It is found that the voltage jump disappeared in sample LLMN and LLMNP and the two voltage plateaus do not exist. This suggests that the two-phase structure is transformed to an one-phase structure in the charging and discharging process [15].

Fig. 7 is the cycle performance of the prepared samples in room temperature (25 ℃) and high temperature (55 ℃) respectively at 1 ℃ rate. The capacity retention rates of SLM, LM, LLM, LLMN and LLMNP are 87.5%, 87.6%, 95.4%, 94.4% and 97.0% respectively after 50 cycles at 25 ℃ and 83.7%, 84.1%, 90.3%, 92.1% and 92.0% at 55 ℃. It indicates that doping can improve the cycle characteristics at both room temperature and high temperature. The sample LLMN and LLMNP doped with niobium have better cycle characteristics than LLM doped with single lithium at high temperature. The coulombic efficiency of these samples is showed in Fig. S3 (Supporting information) during the process of cycling. It also indicates that the sample LLMN and LLMNP have a higher coulombic efficiency than the other samples.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. Cycling performance and coulombic efficiency of the prepared samples at different temperature (a: 25 ℃, b: 55 ℃). | |

In spinel structure, 32 oxide ions form a face centered cubic lattice, and the lithium and manganese ions occupy 8a tetrahedral sites and 16d octahedral sites, respectively [35]. When doping excess lithium ions, part of the lithium ions would replace the manganese ions in 16d octahedral sites, which leads to the content of Mn4+ ions increased to keep the charge balance. Because the radius of Mn4+ ion is smaller than that of Mn3+ ion, the lattice constant would decrease, and the manganese oxide covalent bond strength would also be increased, so the crystal structure became more stable. Doretta Capsoni reported that the capability of a lattice to maintain the undistorted structure is determined by the ratio r = [Mn4+]/[Mn3+] [42]. Jahn-Teller transition can be suppressed when r≥ 1.18. As shown in Table S2 (Supporting information), the r values of LLM, LLMN and LLMNP reach 1.78, 1.56 and 1.63. After doping with niobium and phosphorus, although the crystal structure constant slightly increases, but the r value is greater than 1.18, so LLMN and LLMNP still have good cycle characteristics. Luo [20] reported that the Mn valence in spinel cathodes needs to be >3.6 to offer good cycle ability at 25 ℃ and 55 ℃. The average valences of manganese are 3.522, 3.530, 3.640, 3.610 and 3.625 as shown in Table S2 (Supporting information). The experimental results are consistent with the conclusion.

The cycling features of LLMN and LLMNP are better than that of LLM at high temperature. The reasons may be associated with the morphology of circular arc and smooth surface due to the niobium dopant, which can reduce the contact area between electrode and electrolyte due to the small specific surface area as shown in Table S3 (Supporting information). It is well known that the capacity retention of LMO spinel would typically deteriorate at elevated temperature which is related to the manganese dissolution [31].

Fig. 7 indicates that the sample LLMNP with phosphate ion dopant exhibits the best cycle performance. In this case, the Mn-O distance is increased due to the phosphate doping, thus the polarizing effect exerted by Mn3+ over O2- is decreased, and the positive charge on the Mn atom is increased as well. It produces a beneficial effect that the average valence of manganese would increase when increasing the a-lattice parameter. This effect can be used strategically to diminish the influence of the undesired Jahn-Teller effect on the electrochemical behavior of the LiMn2O4 cathode material through phosphate doping [43]. The electrochemical performance of the optimal sample and some published results of Li-rich spinels are showed in Table S4 (Supporting information) [44-47].

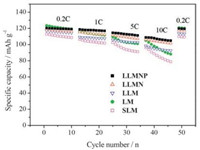

Fig. 8 represents the rate capability of the as-prepared samples at different rates ranging from 0.2 C to 10 C and the recovery ability after the charging and discharging at high rate. It shows that the discharge capacities decrease with the increasing chargedischarge rate. The specific discharge capacity of SLM, LM, LLM, LLMN and LLMNP are 113 mAh g-1, 123 mAh g-1, 117 mAh g-1, 120 mAh g-1 and 119 mAh g-1 at 0.2 C rate, 106.6 mAh g-1, 116.2 mAh g-1, 109.2 mAh g-1, 115.4 mAh g-1 and 118.7 mAh g-1 at 1 C rate, 102.5 mAh g-1, 112.4 mAh g-1, 105.9 mAh g-1, 111.6 mAh g-1 and 114.6 mAh g-1 at 5 C rate, which then decrease to 96 mAh g-1, 105 mAh g-1, 98.5 mAh g-1, 108.3 mAh g-1and 112.8 mAh g-1 at 10 C rate respectively. When the charge-discharge rates reduce from 10 C to 0.2 C, the specific discharge capacity of these samples could be recovered with 2.9%, 2.2%, 2.7%, 1.0%, 0.5% capacity loss. The two samples doped with niobium have more superior rates characteristics than those of the other samples. Doping the phosphate root further improves the rate characteristics. LLMNP has the best cycle characteristics at high rates.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 8. Comparison of the rate capability among these samples. | |

The cyclic voltammograms of the prepared samples are shown in Fig. S4 (Supporting information) at a cutoff voltage between 3.0 V and 4.35 V with a scanning rate of 0.2 mV s-1. The CV curve of the undoped samples SLM and LM shows two sharp anodic and cathodic peaks, it is corresponding to the two voltage plateaus of the charge and discharge curve as shown in Fig. 6. There are two binary equilibrium systems (LiMn2O4-Li0.5Mn2O4 and Li0.5Mn2O4-λMnO2) for normal spinel LiMn2O4 during Li ion intercalation and deintercalation with a 100 mV voltage difference. The first pair redox of the peaks (4.15 V/4.05 V) is attributed to the intercalation/ de-intercalation of lithium ion into the first half of the tetrahedral sites, where Li+ ions do not interact. The second pair of the peaks (about 4.05 V/3.95 V) is attributed to the removal/addition of Li ion from/into the other half of tetrahedral sites inwhich Li/Li+ interaction occurs. It would increase the repulsion between the lithium ions, resulting in a small increase in the free energy in the system as reflected by the observed potential dropping or rising [7, 10]. It can be inferred that the change of structure is rapid in the process of charging and discharging for the un-doped samples SLM and LM, it would lead to final structure damage and deteriorate the cyclic performance. Fig. S4 (Supporting information) also shows that the sample LM has better reversibility than SLM.

The CV of the Li-rich spinel LLM shows two gentle redox peaks. The first pair redox of the peaks (4.15 V/4.05 V) becomes slight bulge for the CVs of LLMN while the two peaks disappear and become one peak for the CVs of LLMNP. It indicates that the structure changes gradually in the process of charging and discharging due to the adding of dopant. It helps to improve the cycle characteristics of LLM, LLMN and LLMNP.

Fig. S4 (Supporting information) also shows that the sample LLMNP has the largest peak current compared with that of other samples at the same scanning rate, so it can be inferred that the sample LLMNP has the highest Li+ ion diffusion coefficient which accounts for an excellent rate capability.

3. ConclusionSpherical LMO spinel was prepared by an ion implanted method assisted by polyalcohol. Compared with the solid phase method, lithium ion can be immersed into the pore of manganese dioxide at a low temperature by the ion implantation method. The materials prepared by the ion implantation method have a high discharge capacity and excellent crystallization.

The LMO material was doped with lithium, niobium, and phosphate simultaneously. The results show that the rich lithium doping can improve the cycle stability at both room temperature and high temperature. Niobium doping can enhance the capacity of Li-rich LMO spinel. The crystal growth along the (111) and (400) planes is reinforced. The crystal grain exhibits circular shape and smooth morphology, so the BET specific surface area is decreased. Phosphate-doped LMO spinel exhibits good high-rate capacity and structure stability. The prepared Li1.09Mn1.87Nb0.031O3.99(PO4)0.021 has a discharge capacity of 119 mAh g-1 at 0.2 C rate and 112.8 mAh g-1 at 10 C rate. The retention rates of the discharge capacity reach 98% at 1 C rate after 50 cycles in 25 ℃ and 94% in 55 ℃.

4. ExperimentalAll the chemical reagents are of analytically pure grade. Reagents and materials used for the electrochemical performance evaluation are specialized for lithium ion battery.

4.1. Synthesis of spherical MnO2 precursorTo prepare spherical MnO2, a redox reaction was adopted in a liquid phase using sodium permanganate solution and manganese chloride as reactant. Firstly, the manganese chloride was dissolved in deionized water with the concentration of 1.5 mol L-1 and the sodium permanganate solution was diluted to 1.5 mol L-1. Then some H2SO4 solution with pH = 5 was added into a reaction kettle which was placed in a 40 ℃ water bath pot. After that, the sodium permanganate and manganese chloride solution were added into the reaction kettle continuously with a feeding speed of 8 mL min-1 by constant flow pump under the condition of stirring. Keep stirring for half an hour after the end of feeding, the mixture was aged for ten hours. Finally, the spherical MnO2 precursor was obtained by filtering, washing and drying. The Mn wt% was measured by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy.

4.2. Synthesis of LiMn2O4 sample by a solid state reaction methodA stoichiometric mixture of lithium hydroxide monohydrate (LiOH·H2O) and spherical MnO2 according to the formula LiMn2O4 was thoroughly mixed by grinding in agate mortar for two hours. The mixture (denoted by SP) then sintered at 800 ℃ for 6 h in air, followed by slow cooling to ambient temperature. The LiMn2O4 sample synthesized by this solid state reaction was marked as SLM.

4.3. Synthesis of LiMn2O4, Li1.1Mn1.9O4, Li1.1Mn1.87Nb0.03O4, Li1.1Mn1.87Nb0.03O3.98(PO4)0.02 samples by an ion implanted methodLithium hydroxide monohydrate (LiOH·H2O) and spherical MnO2 were mixed according to the stoichiometric ratio in LiMn2O4, then 20 wt% ethylene glycol or glycerol was added into the mixture as soluble initiator, lithium hydroxide monohydrate was dehydrated and dissolved with the help of ethylene glycol or glycerol. Meanwhile, lithium ions were implanted into the pore of manganese dioxide under the action of solution heat. Then, a mixed paste was attained. After drying at 80 ℃ for 20 h the mixed paste turned into mixture powder (denoted by IP). The sample IP was calcined at 800 ℃ for 6 h in air atmosphere. The final sample LiMn2O4 was marked as LM. Li1.1Mn1.9O4 (denoted as LLM) was synthesized by the same method. Using niobium pentoxide, diammonium phosphate as dopant, Li1.1Mn1.87Nb0.03O4 (denoted by LLMN) and Li1.1Mn1.87Nb0.03O3.98(PO4)0.02 (denoted by LLMNP) were synthesized by the same method.

4.4. Characterization of the as-prepared samplesThe phase identification of the prepared samples was carried out by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Multiflex X-ray powder diffractometer. X-ray profiles were measured between 10 and 90° (2θ angle) with a monochromatic Cu radiation source. The morphologies of the samples were examined with a JEOLJSM-5600LV scanning electron-microscope (SEM). Thermal analysis was carried out with a TGA/DSC (Setaram Labsys) instrument at a heating rate of 10 ℃ min-1. The BET specific surface area was measured by N2 sorption using surface analyzer Gemini 2360. Elemental analysis was carried out using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) (PROFILE SPEC, USA) to determine the chemical composition of the prepared samples. The present XPS data were collected using an Imaging Xray Photoelectron spectrometer (Axis Ultra, UK) with a monochromatized Al Kα source.

The electrochemical properties of the samples were tested in CR2032 coin-type cells with metallic lithium as anode electrode. Cathode slurries were prepared by mixing 90 wt% spinel LMO, 4 wt % conducting carbon black, and 6 wt% PVDF binder in NMP solvent. Keep stirring for two hours by magnetic force, these slurries were then cast onto an aluminum foil and dried at 120 ℃ in a vacuum oven. Then the foil was punched into circular electrode. The cathode was separated from the Li anode by a layer of celgard 2300 membrane soaked with the electrolyte of 1 mol/L LiPF6 in a 1:1(v/ v) mixture of ethylene carbonate (EC) and dimethyl carbonate (DMC). The cells were assembled in an argon-filled glove box. The charge and discharge curves, cycle performances and rate characteristics of the cells were evaluated on a Land cell tester. Cyclic voltammograms (CVs) were measured with CHI660C type electrochemical workstation.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by a grant from the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) (No. 2008AA11A102).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2017.03.035.

| [1] | N. Nitta, F.X. Wu, J.T. Lee, et al., Li-ion battery materials: present and future. Mater. Today 18 (2015) 252–264. DOI:10.1016/j.mattod.2014.10.040 |

| [2] | G.J. Xu, Z.H. Liu, C.J. Zhang, et al., Strategies for improving the cyclability and thermo-stability of LiMn2O4-based batteries at elevated temperatures. J. Mater. Chem. A 3 (2015) 4092–4123. DOI:10.1039/C4TA06264G |

| [3] | S. Martinez, I. Sobrados, D. Tonti, et al., Chemical vs. electrochemical extraction of lithium from the Li-excess Li1.10Mn1.90O4 spinel followed by NMR and DRX techniques. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16 (2016) 3282–3291. |

| [4] | Y.F. Deng, S.X. Zhao, D.H. Hu, et al., Structure and electrochemical performance of spinel LiMn1.95Ni0.05O3.98F0.02 coated with Li-La-Zr-O solid electrolyte. J. Solid State Electrochem. 18 (2014) 249–255. DOI:10.1007/s10008-013-2265-2 |

| [5] | Z. Zhu, D. Zhang, H. Yan, et al., Precise preparation of high performance spherical hierarchical LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 for 5 V lithium ion secondary batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 1 (2013) 5492–5496. DOI:10.1039/c3ta10980a |

| [6] | T. Nakamura, A. Kajiyama. Synthesis of Li-Mn spinel oxide using Mn2O3 particles. Solid State Ionics 124 (1999) 45–52. DOI:10.1016/S0167-2738(99)00214-3 |

| [7] | W. Liu, K. Kowal, G.C. Farrington. Electrochemical characteristics of spinel phase LiMn2O4-based cathode materials prepared by the pechini process. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143 (1996) 3590–3596. DOI:10.1149/1.1837257 |

| [8] | L.J. Fu, H. Liu, C. Li, et al., Electrode materials for lithium secondary batteries prepared by sol-gel methods. Prog. Mater. Sci. 50 (2005) 881–928. DOI:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2005.04.002 |

| [9] | T. Kanasaku, K. Amezawa, N. Yamamoto. Hydrothermal synthesis and electrochemical properties of Li-Mn-spinel. Solid State Ionics 133 (2000) 51–56. DOI:10.1016/S0167-2738(00)00734-7 |

| [10] | Y.L. Cui, W.J. Bao, Z. Yuan, et al., Comparison of different soft chemical routes synthesis of submicro-LiMn2O4 and their influence on its electrochemical properties. J. Solid State Electrochem. 16 (2012) 1551–1559. DOI:10.1007/s10008-011-1558-6 |

| [11] | C.Y. Zhu, G. Saito, T. Akiyama. A new CaCO3-template method to synthesize nanoporous manganese oxide hollow structures and their transformation to high-performance LiMn2O4 cathodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 1 (2013) 7077–7082. DOI:10.1039/c3ta11066d |

| [12] | Z. Zhu, L. Qi, D. Zhang, et al., Preparation of spherical hierarchical LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 with high electrochemical performances by a novel composite co-precipitation method for 5 V lithium ion secondary batteries. Electrochim. Acta 115 (2015) 290–296. |

| [13] | Y.J. Cai, Y.D. Huang, X.C. Wang, et al., Facile synthesis of LiMn2O4 octahedral nanoparticles as cathode materials for high capacity lithium ion batteries with long cycle life. J. Power Sources 278 (2015) 574–581. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.12.082 |

| [14] | X.N. Ding, H.W. Zhou, G.C. Liu, et al., Electrochemical evaluation of LiAl0.05Ni0.05Mn1.9O4 cathode material synthesized via electrospinning method. J. Alloys Compd. 632 (2015) 147–151. DOI:10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.01.163 |

| [15] | S. Hirose, T. Kodera, T. Ogihara. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of Lirich spinel type LiMn2O4 powders by spray pyrolysis using aqueous solution of manganese carbonate. J. Alloys Compd. 506 (2010) 883–887. DOI:10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.07.104 |

| [16] | Q.T. Zhang, J.T. Mei, X.M. Wang, et al., Facile synthesis of spherical spinel LiMn2O4 nanoparticles via solution combustion synthesis by controlling calcinating temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 617 (2014) 326–331. DOI:10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.08.003 |

| [17] | T.Y.S.P. Putra, M. Yonemura, S. Torii, et al., Structure and electrochemical performance of the spinel-LiMn2O4 synthesized by mechanical alloying. Solid State Ionics 262 (2014) 83–87. DOI:10.1016/j.ssi.2013.10.049 |

| [18] | M. Saitoh, M. Sano, M. Fujita, et al., Studies of capacity losses in cycles and storages for a Li1.1Mn1.9O4 positive electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 151 (2004) A17–A22. DOI:10.1149/1.1630038 |

| [19] | E. Talik, L. Lipińska, P. Zajdel, et al., Electronic structure and magnetic properties of LiMn1.5M0.5O4(M=Al, Mg, Ni, Fe) and LiMn2O4/TiO2 nanocrystalline electrode materials. J. Solid State Chem. 206 (2013) 257–264. DOI:10.1016/j.jssc.2013.08.006 |

| [20] | Q. Luo, A. Manthiram. Effect of low-temperature fluorine doping on the properties of spinel LiMn2-2yLiyMyO4-ηFη (M=Fe, Co, and Zn) cathodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 156 (2009) A84–A88. DOI:10.1149/1.3028317 |

| [21] | Y. Liu, T. Fujiwara, H. Yukawa, et al., Lithium intercalation and alloying efects on electronic structures of spinel lithium manganese oxides. Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells 62 (2000) 81–87. DOI:10.1016/S0927-0248(99)00138-5 |

| [22] | H.B. Sun, Y.G. Chen, C.H. Xu, et al., Electrochemical performance of rare-earth doped LiMn2O4 spinel cathode materials for Li-ion rechargeable battery. J. Solid State Electrochem. 16 (2012) 1247–1254. DOI:10.1007/s10008-011-1514-5 |

| [23] | A. Iturrondobeitia, A. Go, V. Palomares, et al., Effect of doping LiMn2O4 spinel with a tetravalent species such as Si(Ⅳ) versus with a trivalent species such as Ga(Ⅲ). Electrochemical, magnetic and ESR study. J. Power Sources 216 (2012) 482–488. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.06.031 |

| [24] | S.C. Han, S.P. Singh, Y.H. Hwang, et al., Gadolinium-doped LiMn2O4 cathodes in Li ion batteries: understanding the stabilized structure and enhanced electrochemical kinetics. J. Electrochem. Soc. 159 (2012) A1867–A1873. DOI:10.1149/2.009212jes |

| [25] | D.K. Lee, S.C. Han, D. Ahn, et al., Suppression of phase transition in LiTb0.01Mn1.99O4 cathodes with fast Li+ diffusion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4 (2012) 6842–6848. DOI:10.1021/am302003r |

| [26] | X. Liang, S. Zeng, Y. Liu, et al., Enhance cycling performance of LiMn2O4 cathode by Sr2+ and Cr3+ doping. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31 (2015) 443–447. DOI:10.1179/1743284714Y.0000000625 |

| [27] | S. Balaji, T. Mani Chandran, D. Mutharasu. A study on the influence of dysprosium cation substitution on the structural, morphological, and electrochemical properties of lithium manganese oxide. Ionics 18 (2011) 549–558. |

| [28] | S. Jayapal, R. Mariappan, S. Piraman. Dopant depends on morphological and electrochemical characteristics of LiMn2-XMoXO4 cathode nanoparticles. J. Solid State Electrochem. 17 (2013) 2157–2165. DOI:10.1007/s10008-013-2055-x |

| [29] | B. Ebin, G. Lindbergh, S. Gürmen. Preparation and electrochemical properties of nanocrystalline LiBxMn2-xO4 cathode particles for Li-ion batteries by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis method. J. Alloys Compd. 620 (2015) 399–406. DOI:10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.09.098 |

| [30] | S.H. Guo, S.C. Zhang, X.M. He, et al., Synthesis and characterization of Sn-doped LiMn2O4 cathode materials for rechargeable Li-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 155 (2008) A760–A763. DOI:10.1149/1.2965635 |

| [31] | H.R. Lee, B. Lee, K.Y. Chung, et al., Scalable synthesis and electrochemical investigations of fluorine-doped lithium manganese spinel oxide. Electrochim. Acta 136 (2014) 396–403. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2014.05.106 |

| [32] | Y.K. Sun, B. Oh, H.J. Lee. Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of oxysulfide spinel LiAl0.15Mn1.85O3.97S0.03 cathode materials for rechargeable batteries. Electrochim. Acta 46 (2000) 541–546. DOI:10.1016/S0013-4686(00)00629-0 |

| [33] | S.H. Ye, J.K. Bo, C.Z. Li, et al., Improvement of the high-rate discharge capability of phosphate-doped spinel LiMn2O4 by a hydrothermal method. Electrochim. Acta 55 (2010) 2972–2977. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2010.01.018 |

| [34] | Q.L. Jiang, K. Du, Y.B. Cao, et al., Synthesis and characterization of phosphatemodified LiMn2O4 cathode materials for Li-ion battery. Chin. Chem. Lett. 21 (2010) 1382–1386. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2010.04.039 |

| [35] | S.M. Dou. Review and prospects of Mn-based spinel compounds as cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Ionics 21 (2015) 3001–3030. DOI:10.1007/s11581-015-1545-5 |

| [36] | Q.L. Wei, X.Y. Wang, X.K. Yang, et al., The effects of crystal structure of the precursor MnO2 on electrochemical properties of spinel LiMn2O4. J. Solid State Electrochem. 16 (2012) 3651–3659. DOI:10.1007/s10008-012-1809-1 |

| [37] | L. Hernan, J. Morales, L. Sanchez, et al., Sol-gel derived Li-V-Mn-O spinels as cathodes for rechargeable lithium batteries. Solid State Ionics 133 (2000) 179–188. DOI:10.1016/S0167-2738(00)00742-6 |

| [38] | X.J. Yang, H. Kanoh, W.P. Tang, et al., Synthesis of Li1.33Mn1.67O4 spinels with different morphologies and their ion adsorptivities after delithiation. J. Mater. Chem. 10 (2000) 1903–1909. DOI:10.1039/b000219o |

| [39] | W. Xu, A. Yuan, Y. Wang. Electrochemical studies of LiCrxFexMn2-2xO4 in an aqueous electrolyte. J. Solid State Electrochem. 16 (2011) 429–434. |

| [40] | Y.K. Sun, G.S. Park, Y.S. Lee, et al., Structural changes (degradation) of oxysulfide LiAl0.24Mn1.76O3.98S0.02 spinel on high-temperature cycling. J. Electrochem. Soc. 148 (2001) A994–A998. DOI:10.1149/1.1391270 |

| [41] | P. Ragupathy. Understanding the role of manganese valence in 4 V spinel cathodes for lithium-ion batteries: a systematic investigation. RSC Adv. 4 (2014) 670–675. DOI:10.1039/C3RA45689G |

| [42] | D. Capsoni, M. Bini, G. Chiodelli, et al., Inhibition of Jahn-Teller cooperative distortion in spinel by LiMn2O4 transition metal ion doping. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 3 (2001) 2162–2166. DOI:10.1039/b100080m |

| [43] | R. Arabolla Rodríguez, Y. Mosqueda Laffita, E. Perez Cappe, et al., A new strategy toward enhancing the phosphate doping in LixMn2O4 cathode materials. Ceram. Int. 40 (2014) 12413–12422. DOI:10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.04.092 |

| [44] | M. Prabu, M.V. Reddy, S. Selvasekarapandian, et al., (Li, Al)-co-doped spinel Li (Li0.1Al0.1Mn1.8)O4 as high performance cathode for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 88 (2013) 745–755. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2012.10.011 |

| [45] | J.M. Amarilla, K. Petrov, F. Pic, et al., Ni2+, Cr3+, Co3+ y=0.01 and 0.06) spinels characterization and electrochemical behavior at 25 and at 55℃ in rechargeable lithium cells. J. Power Sources 191 (2009) 591–600. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.02.026 |

| [46] | W. Choi, A. Manthiram. Influence of fluorine on the electrochemical performance of spinel LiMn2-y-zLiyZnzO4-ηFη cathodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154 (2007) A614–A618. DOI:10.1149/1.2732169 |

| [47] | W. Choi, A. Manthiram. Comparison of metal ion dissolutions from lithium ion battery cathodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 153 (2006) A1760–A1764. DOI:10.1149/1.2219710 |

2017, Vol. 28

2017, Vol. 28