Chemotherapy is at the forefront of treatment against cancer because of its high efficiency and convenience [1, 2]. Unfortunately, conventional chemotherapy has shown several side effects including poor bioavailability, high toxicity and non-specificity [3-5]. To address these problems, the developments of prodrug strategies for sidestepping side effects have been used to directly enhance therapeutic efficiency; these strategies usually involve drug delivery systems, which can be activated by endogenous or exogenous substances and release the anticancer drug in tumor tissues [6-9]. However, in situ monitoring of the drug's release and localization in tumor is yet to be fully exploited.

Prodrug might become a promising approach to integrate chemotherapy and diagnostics, and this approach has become attractive for activating and monitoring drug release at the unique tumor microenvironment, thereby the therapeutic effect of anticancer drugs could be significantly improved [10-14]. The special environments of tumor cells include intracellular reduction [15-17], lower pH [18, 19] hypoxia [20, 21], active oxygen species [22, 23] or over-expressed enzymes [24, 25]. Among them, overexpressed enzymes in cancer cells draw particular interest as an anticancer drug-releasing trigger (mechanism) because of the differences of the enzymes' levels between tumor and normal cells.

Cleavable prodrugs have shown excellent capability to mediate the release of drug molecules and fluorophore simultaneously via the cleavage of a single linker [26]. A series of cleavable linkers for prodrugs have been developed in recent years, which indicated that cleavable prodrugs are conductive to monitoring drug release and therapeutic effect as well as the trigger (usually biomarker) level [27, 28]. Recently, coumarin has been adopted as a suitable fluorophore in biochemistry, which show low cytotoxicity, high quantum yield, easy modification and some optical beneficial characteristics (ICT effect, photo-responsive feature, two-photon excitation and so on). Many coumarin derivatives have been widely reported as fluorescent probes for detection of different biomarkers or assessment of drug release [29-31].

The liposomes, as a FDA-approved drug delivery carrier, have been widely utilized for drug delivery [32-34]. Liposomes are defined as self-assembled vesicles, which are composed of one or multiple concentric lipid bilayers and enclose an aqueous core. The advantages of utilizing liposomes as drug carrier include improving solubility for the encapsulated drug, reducing the drug's sideeffects and toxicity, protecting the drug against chemical and biological degradation during the drug delivery, and enhancing biocompatibility [35].

Carboxylesterase (CaE) mediates the hydrolysis of carboxylic acid ester into alcohols and acids [36-38]. This enzyme acts not only as a catalyst that has been widely used in organic synthesis or industrial production, but also as a key participant that works in drug metabolism and detoxification. CaE has been found in most of human tissues, especially in liver, kidney, heart, small intestine and blood. It has been reported that CaE is overexpressed in some types of cancer cells, and the CaE level is significantly different between these cancer cells and normal tissues [39, 40]. CaE also has been employed as a biomarker; and to date, a number of CaE level assays have been employed for cancer diagnosis [41, 42], but there are still few reports on the exploitation of this enzyme as a trigger for prodrug.

Considering the physiological and pathological significance of CaE, herein we fabricated a novel prodrug for which the drug release is achieved via employing the overexpressed CaE in tumor cells as the trigger (activating means), as shown in Scheme 1. This prodrug system contains an acetyl unit as the responsive unit toward CaE and the coumarin unit as the scaffold for building the cleavable linker and the reporter fluorophore for monitoring the release of anticancer drug (chlorambucil). This CaE-activatable prodrug system has several striking features: (1) the coumarin scaffold not only acts as the reporting fluorophore for assessing CaE level but also as a cleavable architecture for releasing the drug; (2) the acetyl group serves as the enzyme-responsive unit and quencher for coumarin's fluorescence via intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) [43]; (3) to evaluate the prodrug's performance, the prodrug is encapsulated into liposomes, which can enhance aqueous solubility/dispersibility and in the meantime reduce the nonspecific side effects. As for the prodrug, upon activation by the enzyme CaE, the ICT effect is diminished by the cleavage of the bond between the fluorophore (coumarin) and the quencher (acetyl group); due to the cleavable reaction, the active drug and the fluorophore are released simultaneously; consequently, the coumarin's fluorescence is restored.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme1. Structure of prodrug and mechanism of this prodrug for drug release and imaging in HeLa cells. | |

2. Results and discussion 2.1. Synthesis

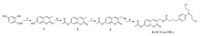

The synthesis route for the prodrug 4 (AC-Cou-CBL) is depicted in Scheme 2. Compound 1 was synthesized from 2, 4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde, sodium propionate and propionic anhydride in the presence of piperidine. Then compound 1 was reacted with acetic anhydride to yield compound 2. Bromination of compound 2 was accomplished with N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and benzoyl peroxide (BPO), affording compound 3. Finally, compound 4 was prepared by nucleophilic reaction of chlorambucil (CBL, anticancer drug) with compound 3. The structures of all the synthesized compounds were confirmed by 1H NMR and HR-Mass spectrometry (Figs. S1-S9 in Supporting information). In addition, for comparison, a control compound 8 (Pro-Cou-CBL, namely the prodrug with the acetyl group being replaced by an ether group), and the characterizations for the control compound (1H NMR and HR-Mass) are shown in Figs. S10-S16 (Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme2. Synthetic route for the prodrug AC-Cou-CBL (compound 4). Reagents and conditions: (a) sodium propionate, piperidine, propionic anhydride, 140 ℃, 6 h; (b) CH2Cl2, Ac2O and pyridine, r.t., 12 h; (c) N-Bromosuccinimide (NBS), benzoyl peroxide (BPO), CCl4, reflux, 4 h; (d) chlorambucil (CBL), DMF, potassium carbonate, r.t., 3 h. | |

2.2. Drug release studies

To verify the release of anticancer drug CBL from the prodrug AC-Cou-CBL was triggered by CaE, UV and fluorescence spectra were recorded under physiological conditions (37 ℃, pH 7.4, 10 μmol/L phosphate buffer). As shown in Fig. S17 (Supporting information), the strong absorption of AC-Cou-CBL and 2-OHcoumarin are at 320 nm and 370 nm. The fluorescence of AC-CouCBL shows weak emission at 462 nm due to the ICT effect resulted from the presence of acetyl moiety in the coumarin scaffold; however, a 400-fold enhancement in emission intensity at 462 nm occurs in the presence of CaE, and this spectrum is in accord with that of 2-OH-coumarin (Fig. 1A, fluorescence at 462 nm). In addition, the time and concentration dependence of the AC-CouCBL fluorescence were also investigated, as shown in Fig. 1B and C. The fluorescence at 462 nm increases 400-fold due to the biochemical reaction activated by CaE, reaching a plateau in 100 min. On stepwise addition of CaE (0-200 U/L) to AC-Cou-CBL, the fluorescence intensity at 462 nm increases until it reaches a saturation point at 200 U/L. To check whether the fluorescence signal of the released fluorophore (2-OH-coumarin) can be employed to monitor drug release, we conducted the experiments to investigate the correlation between the fluorescence signal and drug release. Fig. S18 shows the correlation analysis of fluorescence intensity for varied concentrations of 2-OH-Coumarin (0-5 μmol/ L) as well as that of AC-Cou-CBL (0-5 μmol/L) in the presence of 100 U/L CaE; the linear relationship clearly indicates that, the fluorescence of the released and thus activated 2-OH-coumarin can serves as the reporting signal for detecting the enzyme level and monitoring drug release. All these results indicate that CBL can be released from AC-Cou-CBL successfully in the presence of CaE.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (A) Fluorescence spectra of the AC-Cou-CBL (5 μmol/L), 2-OH-coumarin (5 μmol/L) and AC-Cou-CBL (5 μmol/L) with CaE (100 U/L) for 1 h. (B) Timedependent fluorescence spectra for the AC-Cou-CBL (5 μmol/L) with CaE (100 U/L).Inset: Change in fluorescence intensity at 462 nm as a function of time after CaE (100 U/L) treatment. (C) Fluorescent spectra for AC-Cou-CBL (5 μmol/L) with CaE (0-200 U/L) for 1 h. Inset: Change in fluorescence intensity at 462 nm as a function of CaE concentration. (D) Percentage of CBL (as determined by HPLC) released from the AC-Cou-CBL (5 μmol/L) as a function of time with or without CaE (100 U/L). | |

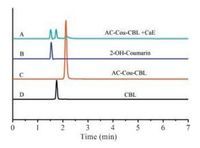

In order to confirm the release of CBL from AC-Cou-CBL upon the activation by CaE, HPLC and high resolution MS spectrum were employed for verification (Fig. 1D, Fig. 2, and Fig. S19 in Supporting information). As shown in Fig. 1D, CBL can be released from the prodrug in the presence of CaE (100 U/L) based on HPLC measurement, whereas no drug release can be detected in the absence of CaE. In Fig. 2, the retention time of AC-Cou-CBL, 2-OHcoumarin and CBL are identified at 2.12 min, 1.53 min and 1.75 min respectively in HPLC chromatogram. Furthermore, AC-Cou-CBL was reacted with CaE and then a small aliquot was subjected to HRMS analysis. Ionic peaks corresponding to CBL ([M+H]+ = 304.0875), 2-OH-coumarin ([M+H]+ = 193.0497) and ACCou-CBL ([M+H]+ = 520.1309) can be observed in the HR-MS spectra, clearly indicating that the active drug CBL could be released from the AC-Cou-CBL (Fig. S19). These results provide evidence that the anticancer drug CBL is indeed released from the prodrug through CaE mediated cleavable reaction.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Typical HPLC chromatogram of the AC-Cou-CBL (10 μmol/L) incubated with CaE (100 U/L) (A), 2-OH-Coumarin (B), AC-Cou-CBL (C) and CBL (D). Peaks in the chromatograms were detected by monitoring the absorption at 320 nm (CBL and AC-Cou-CBL), 370 nm (2-OH-Coumarin). The mobile phase was 80/20 MeOH/water and the flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. | |

2.3. Selectivity

Fig. S20 (Supporting information) shows the effect of pH on CaE-activated reaction of AC-Cou-CBL. In the presence of CaE, obvious increment of emission intensity can be detected and remains relatively stable in the pH range of 4-10. In the absence of CaE, the emission intensity of AC-Cou-CBL is weak and keeps stable over a pH range of 4-8 and there is slight increase of fluorescence intensity at pH range of 9-10. These results show that, under physiological conditions, AC-Cou-CBL may be useful as a prodrug for releasing CBL in tumor tissues where CaE is overexpressed.

To assess whether other biologically relevant substances will affect the cleavage reaction of AC-Cou-CBL upon activation by CaE, AC-Cou-CBL was reacted with these substances respectively. As depicted in Fig. 3A, for the prodrug, significant fluorescence intensity at 462 nm can only be observed in the presence of CaE, while there is no obvious enhancement for other potential interferents. In addition, we also assessed the performance of this carboxylesterase-based prodrug in human serum (which contains various proteins and could show possible background to hydrolysis of the prodrug). As shown in Fig. 3B, the prodrug in human serum with 100 U/L CaE displays remarkable changes in fluorescence intensity at 462 nm and this result is similar to that of 2-OH-Coumarin (5 μmol/L) in human serum. In order to enhance the biocompatibility and reduce side-effects, we constructed a liposome nanoparticle containing AC-Cou-CBL (referred to as LIPAC-Cou-CBL, Fig. S21 in Supporting information) and evaluated its performance in human serum. Fig. 3B shows that the fluorescence intensity of LIP-AC-Cou-CBL without the addition of CaE is lower than that of AC-Cou-CBL in human serum, and this result indicates a higher stability of the liposomal nanoparticle. Meanwhile, we also investigated the LIP-AC-Cou-CBL with 100U/L CaE in serum, and the result shows that the fluorescence intensity is much weaker than that of AC-Cou-CBL upon addition of CaE; and this indicates that the liposome can offer protection for the prodrug. All these results demonstrate that, the fluorescence enhancement resulted from the cleavage reaction is indeed caused by CaE, and also provides further evidence that CBL and 2-OH-coumarin can be released from the prodrug AC-Cou-CBL.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (A) Fluorescence intensity for the prodrug (5 μmol/L) at 462 nm in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 10 μmol/L, containing 2% (v/v) DMSO) in the presence of various relevant species for 1 h. Excitation wavelength: 405 nm. (100 U/L for carboxylesterase (CaE), nitroreductase (NTR), azoreductase (AZD), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and DT-diaphorase (DTD) respectively; 50 μmol/L for Hcy, GSH, Cys, Lys, Phe, Arg, DTT and Gly respectively; 100 μmol/L for others respectively). (B) Fluorescence intensity at 462 nm. (a) AC-Cou-CBL (5 μmol/L) in serum without the addition of CaE for 1 h; (b) 2-OH-coumarin in serum without the addition of CaE for 1 h; (c) AC-Cou-CBL (5 μmol/L) in serum with the addition of CaE (100 U/L) for 1 h; (d) LIP-AC-Cou-CBL (40 μg/mL) in serum without the addition of CaE for 1 h; (e) LIPAC-Cou-CBL (40 μg/mL) in serum with the addition of CaE (100 U/L) for 1 h. | |

2.4. Drug release studies in HeLa cells

HeLa cells were employed for drug release studies in cells. Upon incubation with AC-Cou-CBL for 0.5h, we can observe blue intracellular fluorescence in HeLa cells, and much brighter fluorescence can be detected for 1h of incubation, as shown in Fig. 4A. In order to improve aqueous solubility/dispersibility and enhance cellular uptake of the AC-Cou-CBL, we also evaluated LIPAC-Cou-CBL performance in cells. As for the liposomal nanoparticles, much stronger fluorescence can be detected in HeLa cells (Fig. 4B). Therefore, the prodrug can be used to monitor the drug release process in HeLa cells, given the fact that the fluorophore 2-OH-coumarin can be effectively released from the prodrug.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Fluorescent microscopic images for HeLa cells in the absence (the control) or presence of the AC-Cou-CBL (10 μmol/L) (A), LIP-AC-Cou-CBL (40 μg/mL) (B) with the incubation time of0.5h or 1h respectively. (C) Cell viability profiles for HeLa cell line treated with the LIP-AC-Cou-CBL and LIP-Pro-Cou-CBL of varied concentrations for 48h. (D) Flow cytometry analysis for apoptosis of HeLa cells induced by LIP-ProCou-CBL (0-80 μg/mL) nanoparticles. | |

To investigate the therapeutic effect of LIP-AC-Cou-CBL against cancer cells, the cytotoxicity of HeLa cells was assessed using typical MTT assays (Fig. 4C). The prodrug shows high cytotoxicity to HeLa cells and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the prodrug is 15.2 μg/mL. In Fig. S25 (Supporting information), we also performed the cytotoxicity for 2-OH-coumarin and employed CBL as a positive control, the results indicate that the IC50 of CBL is 9.6 μmol/L and 2-OH-coumarin (IC50>80 μmol/L) exhibits low cytotoxicity. Furthermore, flow cytometry studies were used to further verify the cell apoptosis of LIP-AC-Cou-CBL with varied concentrations of the prodrug (0-80 μg/mL). After incubation for 2h, the apoptotic percentage (including the early and late apoptosis, Q1 and Q4 in Fig. 4D) induced by LIP-AC-CouCBL gradually increases (from 0.7% to 73.4%), as the prodrug concentration is increased. All these results demonstrate that the prodrug shows quite good therapeutic effect in HeLa cells.

2.5. Verification of the release mechanism by control compoundTo further verify the release mechanism, the ester bond (between CBL and coumarin of AC-Cou-CBL) can be hydrolyzed by CaE and CBL can be released. Therefore, we synthesized a control compound 8 (Pro-Cou-CBL) to investigate whether or not the releaseof CBL is caused by the cleavable reactions starting from the hydrolysis of the ester bond. As shown in Scheme S1, the control compound Pro-Cou-CBL which has no ester-responsive group (acetyl group) was treated with CaE (100U/L) for 1h, and then monitored by fluorescence and HPLC. As is expected, we can not observe the enhancement of fluorescence (Fig. S22 in Supporting information) and the CBL peak in HPLC chromatogram (Fig. S23 in Supporting information). Meanwhile, we also evaluate the performance of the LIP-Pro-Cou-CBL (Fig. S21) in HeLa cells.The cell cytotoxicity and cell imaging experimental results demonstrate that Pro-Cou-CBL can't release coumarin fluorophore and the anticancer drug CBL (Fig. 4C and Fig. S24 in Supporting information). These results prove that the release of drug is cause by the cleavable reactions triggered by CaE.

3. ConclusionIn this work, we developed a CaE-activatable prodrug, which can release anticancer drug CBL and restore the fluorescence of the coumarin fluorophore (2-OH-coumarin) through cleavable reaction in the presence of CaE. The prodrug was also encapsulated in liposomes for improving stable and enhancing biocompatibility; upon incubation with cancer cells, these liposomal nanoparticles can release the coumarin fluorophore and exhibit quite good therapeutic effect. This strategy may provide some helpful insights for designing prodrugs using enzyme as the trigger.

4. Experimental 4.1. Materials2, 4-Dihydroxybenzaldehyde, sodium propionate, N-bromosuccinimide (NBS), benzoyl peroxide (BPO), chlorambucil (CBL) and esterase were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Reagents without further purification. Human serum was supplied by The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University. N, N-Dimethyl-formamide (DMF) was dried with CaH2 and distilled under nitrogen atmosphere. The water used was the triple-distilled water which was further treated by ion exchange columns. Other solvents used in this study were analytical grade reagents and used without further purification.

4.2. Measurements1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV 500MHz or 600MHz NMR spectrometer. High resolution mass spectra were obtained on AB Sciex Triple TOF 5600+ mass spectrometer. UV-vis spectra were recorded at 37 ℃ on a Hitachi U-3010 UV-vis spectrophotometer. Fluorescence spectra were recorded at 37 ℃ on a Hitachi F-4600 fluorescence spectrophotometer. Fluorescence images were obtained using an Olympus IX 71 with a DP72 color CCD. The particle size and distribution were determined through dynamic light scattering (DLS) on a Malvern Nano-ZS90 particle size analyzer at a fixed angle of 90° at 25 ℃. Transmission electronic microscopy (TEM) experiments were carried out by mounting a drop (~15 μL) of the solution onto a carbon-coated copper grid and observed on a JEM-2010HR transmission electron microscopy (Japan).

4.3. Synthesis of compound 1-4Synthesis of 7-hydroxy-3-methyl-2H-chromen-2-one (1) : A mixture of 2, 4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (1.5 g, 10.8 mmol), sodium propionate (2.25 g, 23.4 mmol), piperidine (150 μL, 1.5 mmol) and propionic anhydride (4 mL, 31.04 mmol) was refluxed at 140 ℃ for 6 h and then poured into ice. Then a 0.1 mol/L solution of HCl was added in the aqueous mixture, which yielded a milky flocculent precipitate. The precipitate was filtered and treated under stirring with concentrated H2SO4 (3 mL) for 30 minutes. The obtained mixture was poured into ice again to afford brown residue, which was purified by column chromatography over silica gel eluting with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (2:1) to afford 1 (1.5 g, 82% yield) as pale solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, -DMSO-d6) : δ 10.37 (s, 1H), 7.74 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.45-7.39 (m, 1H), 6.76 (dd, 1H, J = 8.4, 2.2 Hz), 6.70 (d, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz, ), 2.03 (s, 3H). HR-MS (ESI): calcd. for C10H8O3 ([M+H]+) 175.0401, found: 175.0403.

Synthesis of 3-methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-7-yl acetate (2) : To the solution of 1 (1.76 g, 10 mmol) in 50 mL CH2Cl2 were added Ac2O (19 mL, 20 mmol) and 3 mL pyridine. The mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature and concentrated subsequently. The residue was extracted with CH2Cl2 (30 mL, 3 times) and the organic layer was washed with water and saturated aqueous NaCl respectively and then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After the evaporation of the solvent, the residue was then purified by column chromatography over silica gel eluting with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (4:1) to afford 2 (2.10 g, 96% yield) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) : δ 7.51 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.09 (d, 1H, J = 2.1 Hz), 7.02 (dd, 1H, J = 8.4, 2.2 Hz), 2.34 (s, 3H), 2.21 (d, 3H, J = 0.9 Hz). HR-MS (ESI): calcd. for C12H10O4 ([M +H]+) 219.0652, found: 219.0654.

Synthesis of acetic acid 3-bromomethyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-7-yl ester (3) : To the solution of 2 (1.09 g, 5 mmol) in 30 mL carbon tetrachloride were added N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) (0.89 g, 5 mmol) and 40 mg benzoyl peroxide (BPO). The mixture was stirred under reflux for 4 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the insoluble residue was filtered off and the filtrate was concentrated and then the residue was then purified by column chromatography over silica gel eluting with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (4:1) to afford 3 (1.15 g, 77% yield) as white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) : δ 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.51 (d, 1H, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.14 (d, 1H, J = 2.1 Hz), 7.08 (dd, 1H, J = 8.5, 2.1 Hz), 4.42 (s, 2H), 2.35 (s, 3H). HR-MS (ESI): calcd. for C12H9BrO4 ([M+H]+) 296.9757, found: 296.9756.

Synthesis of 4-{4-[bis-(2-chloro-ethyl)-amino]-phenyl}-butanoic acid 7-acetoxy-2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-ylmethyl ester (4) : To the solution of 3 (99 mg, 0.33 mmol) in 3 mL dry N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were added chlorambucil (CBL) (101 mg, 0.33 mmol) and potassium carbonate (23 mg, 0.165 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h and extracted with 20 mL CH2Cl2 and the organic layer was washed with water, saturated aqueous 50 mL NaCl respectively and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After the evaporation of the solvent, the residue was then purified by column chromatography over silica gel eluting with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (4:1) to afford 4 (150 mg, 86.5% yield) as pale yellow solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) : δ 7.73 (s, 1H), 7.50 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.13 (d, 1H, J = 2.1 Hz), 7.10-7.04 (m, 3H), 6.63 (d, 2H, J = 8.5 Hz), 5.05 (s, 2H), 3.70 (t, 4H, J = 7.1 Hz), 3.62 (t, 4H, J = 7.0 Hz), 2.58 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.42 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.34 (s, 3H), 2.01-1.89 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) : δ 173.12, 168.68, 159.93, 154.14, 153.16, 144.41, 140.35, 130.36, 129.72, 128.74, 123.18, 118.64, 116.57, 112.21, 110.26, 61.02, 53.61, 40.53, 33.93, 33.46, 26.63, 21.13. HR-MS (ESI): calcd. for C26H27Cl2NO6 ([M+H]+) 520.1298, found: 520.1304.

4.4. In vitro drug release studyThe experiments for in vitro drug release were conducted in PBS solutions (pH 7.4, 10 μmol/L) containing 2% (v/v) DMSO or in human serum. The final concentration of the serum in the test solution is 10-fold diluted. Fluorescent spectra of AC-Cou-CBL (5 μmol/L) reacted with or without CaE (100 U/L) for 1 h in both PBS solutions and human serum were recorded. Fluorescence spectra of AC-Cou-CBL (5 μmol/L) reacted with CaE (100 U/L) for varied time (0-120 min) or varied CaE concentrations (0-200 U/L) in 1 h in PBS and varied AC-Cou-CBL concentrations (0-5 μmol/L) with CaE (100 U/L) for 1 h in human serum were recorded. Fluorescent spectra of LIP-AC-Cou-CBL (40 μg/mL) with or without CaE (100 U/L) in human serum were recorded. Fluorescent spectra of varied 2-OH-Coumarin (0-5 μmol/L) were recorded as well. The excitation wavelength was set at 405 nm and emission was recorded from 420-600 nm with excitation and emission slits of 5 nm, volt 500 V.

4.5. Fabrication of liposomal nanoparticles (LIP-AC-Cou-CBL or LIPPro-Cou-CBL)A DMSO (100 μL) solution of AC-Cou-CBL or Pro-Cou-CBL (10 mg) was diluted with THF (1.9 mL) and the DSPE-PEG 2000 (10 mg) was also dissolved in 1 mL THF, which were added dropwise into 20 mL water under sonication for 20 min at 4 ℃. The mixture was then stirred at room temperature for 24 h. After stirring, THF was removed at 37 ℃ under reduced pressure and the residual solution underwent dialysis with water (cut-off MW 1000). The suspension was centrifuged at 12, 000 rpm for 15 min at 4 ℃ to collect the nanoparticles. After washing three times, the nanoparticles were resuspended in the water (10 mL).

4.6. Cell culturesCervical cancer (HeLa) cell lines were incubated in DMEM medium (10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 ℃.

4.7. Cellular uptake of AC-Cou-CBL and LIP-AC-Cou-CBL in HeLa cellsIn vitro uptake of AC-Cou-CBL and LIP-AC-Cou-CBL was studied with the usage of fluorescence microscopy in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were cultured in a 30 mm 6-well plate with the polylysine-coated cell culture glass slides inside in complete DMEM. The cells were cultured at 37 ℃ in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. After 24 h incubation, the culture medium was removed, and then the cells were washed with PBS buffer three times and subsequently ACCou-CBL (10 μmol/L) and the diluted LIP-AC-Cou-CBL solutions (40 μg/mL) with DMEM were added. The cells were continuously cultured for 0.5 and 1 h respectively at 37 ℃. Then, after culture medium being removed, the cells were washed with PBS buffer for three times and the glass slides were taken out to image on an Olympus IX71 inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a DP72 color CCD.

4.8. Cell viability assay (MTT assay)The cell viability experiment to evaluate the LIP-AC-Cou-CBL, LIP-Pro-Cou-CBL, CBL and 2-OH-coumarin cytotoxicity toward HeLa cell line was carried out by MTT viability assay. In the MTT assay, cells well were seeded in a 96-well plate in 200 μL of DMEM medium. The cells were continued to incubate for 24 h. 200 μL PBS was used to wash each well after the removal of DMEM medium. 200 μL of a medium containing LIP-AC-Cou-CBL (from 0 to 150 μg/mL) was added respectively. The cells were incubated for 48 h. After the removal of DMEM medium, 20 mL of 5 μg/mL MTT assay stock solution in PBS was added into each well and the cells were incubated for another 4 h, then the medium containing unreacted MTT was removed. 200 mL of DMSO was added into each well to dissolve the obtained blue formazan crystals, and the absorbance at 490 nm was recorded on a Thermo MK3 ELISA plate reader to calculate the cell viability.

4.9. Apoptosis with flow cytometry assaysHeLa cells were seeded in a 6-well plate with 2 mL of complete DMEM in each well and incubated for 24 h. After the removal of DMEM medium and washed with PBS, various concentrations of LIP-AC-Cou-CBL (0-80 μg/mL) were added to each well respectively and incubated at 37 ℃ for 2 h. HeLa cells without the treatment were used as a control. Floating and attached cells were both collected and washed with PBS for a quantified determination. The cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488 FITC-conjugated annexin V and PI according to the manufacturer's instructions to evaluate cell apoptosis. Finally, the flow cytometry analyses were performed using BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer and the data were analyzed using the BD Biosciences software.

AcknowledgmentsWe gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (No.201607020015) and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2014A010105009).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2017.04.024.

| [1] | R. Kumar, W.S. Shin, K. Sunwoo, et al., Small conjugate-based theranostic agents:an encouraging approach for cancer therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44(2015)6670–6683. DOI:10.1039/C5CS00224A |

| [2] | Z.L. Liu, Z.Y. Zhou, W. Tian, et al., Discovery of novel 2-n-aryl-substituted benzenesulfonamidoacetamides:orally bioavailable tubulin polymerization inhibitors with marked antitumor activities. Chem. Med. Chem. 7(2012)680–693. DOI:10.1002/cmdc.v7.4 |

| [3] | J. Zhou, X.W. Du, N. Yamagata, B. Xu. Enzyme-instructed self-assembly of small d-peptides as a multiple step process for selectively killing cancer cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138(2016)3813–3823. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b13541 |

| [4] | X.H. Liang, Y. Sun, L.S. Liu, et al., Regioselective synthesis and initial evaluation of a folate receptor targeted rhaponticin prodrug. Chin. Chem. Lett. 23(2012)1133–1136. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2012.08.006 |

| [5] | K.T. Nguyen, Y.L. Zhao. Engineered hybrid nanoparticles for on-demand diagnostics and therapeutics. Acc. Chem. Res. 48(2015)3016–3025. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00316 |

| [6] | Y. Zhou, H. Li, Y.W. Yang. Controlled drug delivery systems based on calixarenes. Chin. Chem. Lett. 26(2015)825–828. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2015.01.038 |

| [7] | Z.Q. Yu, Q. Xu, C.B. Dong, et al., Self-assembling peptide nanofibrous hydrogel as a versatile drug delivery platform. Curr. Pharm. Des. 21(2015)4342–4354. DOI:10.2174/1381612821666150901104821 |

| [8] | H.X. Wang, H.Y. Xie, J.P. Wu, et al., Structure-based rational design of prodrugs to enable their combination with polymeric nanoparticle delivery platforms for enhanced antitumor efficacy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53(2014)11532–11537. DOI:10.1002/anie.201406685 |

| [9] | K. Ulbrich, K. Holá, Šubr V., et al., Targeted drug delivery with polymers and magnetic nanoparticles:covalent and noncovalent approaches, release control, and clinical studies. Chem. Rev. 116(2016)5338–5431. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00589 |

| [10] | Z.Q. Yu, R.M. Schmaltz, T.C. Bozeman, et al., Selective tumor cell targeting by the disaccharide moiety of bleomycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135(2013)2883–2886. DOI:10.1021/ja311090e |

| [11] | S. Santra, C. Kaittanis, O.J. Santiesteban, J.M. Perez. Cell-specific, activatable, and theranostic prodrug for dual-targeted cancer imaging and therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133(2011)16680–16688. DOI:10.1021/ja207463b |

| [12] | X.Y. Wu, X.C. Li, J. Mi, J. You, L. Hai. Design, synthesis and preliminary biological evaluation of brain targeting L-ascorbic acid prodrugs of ibuprofen. Chin. Chem. Lett. 24(2013)117–119. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2013.01.022 |

| [13] | D. Montagner, S.Q. Yap, W.H. Ang. A fluorescent probe for investigating the activation of anticancer platinum(iv) prodrugs based on the cisplatin scaffold. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52(2013)11785–11789. DOI:10.1002/anie.v52.45 |

| [14] | X.M. Wu, X.R. Sun, Z.Q. Guo, et al., In vivo and in situ tracking cancer chemotherapy by highly photostable NIR fluorescent theranostic prodrug. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(2014)3579–3588. DOI:10.1021/ja412380j |

| [15] | L.L. Zhang, H.K. Zhu, C.C. Zhao, X.F. Gu. A near-infrared fluorescent probe for monitoring fluvastatin-stimulated endogenous H2S production. Chin. Chem. Lett. 28(2017)218–221. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2016.07.008 |

| [16] | J. Wu, L.L. Zhao, X.D. Xu, et al., Hydrophobic cysteine poly(disulfide)-based redox-hypersensitive nanoparticle platform for cancer theranostics. Angew. Chem. Int. 54(2015)9218–9223. DOI:10.1002/anie.201503863 |

| [17] | B. Spangler, S.D. Fontaine, Y.H. Shi, et al., A novel tumor-activated prodrug strategy targeting ferrous iron is effective in multiple preclinical cancer models. J. Med. Chem. 59(2016)11161–11170. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01470 |

| [18] | J.Q. Fan, G. Fang, F. Zeng, X.D. Wang, S.Z. Wu. Water-dispersible fullerene aggregates as a targeted anticancer prodrug with both chemo-and photodynamic therapeutic actions. Small 9(2013)613–621. DOI:10.1002/smll.v9.4 |

| [19] | J.Z. Du, X.J. Du, C.Q. Mao, J. Wang. Tailor-made dual ph-sensitive polymerdoxorubicin nanoparticles for efficient anticancer drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133(2011)17560–17563. DOI:10.1021/ja207150n |

| [20] | T. Thambi, J.H. Park, D.S. Lee. Hypoxia-responsive nanocarriers for cancer imaging and therapy:recent approaches and future perspectives. Chem. Commun. 52(2016)8492–8500. DOI:10.1039/C6CC02972H |

| [21] | E. Miranda, I.K. Nordgren, A.L. Male, et al., A cyclic peptide inhibitor of hif-1 heterodimerization that inhibits hypoxia signaling in cancer cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135(2013)10418–10425. DOI:10.1021/ja402993u |

| [22] | X.X. Sun, M.D. Ai, Y. Wang, et al., Selective induction of tumor cell apoptosis by a novel P450-mediated reactive oxygen species (ROS) inducer methyl 3-(4-nitrophenyl) propiolate. J. Biol. Chem. 288(2013)8826–8837. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M112.429316 |

| [23] | A.M. Durantini, E.L. Greene, R. Lincoln, S.R. Martínez, G. Cosa. Reactive oxygen species mediated activation of a dormant singlet oxygen photosensitizer:from autocatalytic singlet oxygen amplification to chemicontrolled photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138(2016)1215–1225. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b10288 |

| [24] | J. Wang, Y.L. Wu, F. Zeng, S.L. Huang, S.Z. Wu. AIE fluorophore with enhanced cellular uptake for tracking esterase-activated release of taurine and ROS scavenging. Faraday Discuss. 196(2017)335–350. DOI:10.1039/C6FD00118A |

| [25] | C.E. Callmann, C.V. Barback, M.P. Thompson, et al., Therapeutic enzymeresponsive nanoparticles for targeted delivery and accumulation in tumors. Adv. Mater. 27(2015)4611–4615. DOI:10.1002/adma.v27.31 |

| [26] | M.E. Roth, O. Green, S. Gnaim, D. Shabat. Dendritic, oligomeric, and polymeric self-immolative molecular amplification. Chem. Rev. 116(2016)1309–1352. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00372 |

| [27] | Sloniec-Myszk J., Resch-Genger U., A. Hennig. Chiral, j-aggregate-forming dyes for alternative signal modulation mechanisms in self-immolative enzymeactivatable optical probes. J. Phys. Chem. B 120(2016)877–885. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b10526 |

| [28] | J.L.M. Jourden, K.B. Daniel, S.M. Cohen. Investigation of self-immolative linkers in the design of hydrogen peroxide activated metalloprotein inhibitors. Chem. Commun. 47(2011)7968–7970. DOI:10.1039/c1cc12526e |

| [29] | W.D. Ji, N.J. Li, D.Y. Chen, et al., Coumarin-containing photo-responsive nanocomposites for NIR light-triggered controlled drug release via a twophoton process. J. Mater. Chem. B 1(2013)5942–5949. DOI:10.1039/c3tb21206h |

| [30] | L.W. He, Q.Y. Xu, Y. Liu, et al., Coumarin-based turn-on fluorescence probe for specific detection of glutathione over cysteine and homocysteine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7(2015)12809–12813. DOI:10.1021/acsami.5b01934 |

| [31] | C. Kumari, D. Sain, A. Kumar, et al., Intracellular detection of hazardous Cd2+ through a fluorescence imaging technique by using a nontoxic coumarin based sensor. Dalton Trans. 46(2017)2524–2531. DOI:10.1039/C6DT04833A |

| [32] | H.L. Gao, Q.Y. Zhang, Z.Q. Yu, Q. He. Cell-penetrating peptide-based intelligent liposomal systems for enhanced drug delivery. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 15(2014)210–219. DOI:10.2174/1389201015666140617092552 |

| [33] | F. Lei, W. Fan, X.K. Li, et al., Design, synthesis and preliminary bio-evaluation of glucose-cholesterol derivatives as ligands for brain targeting liposomes. Chin. Chem. Lett. 22(2011)831–834. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2010.12.056 |

| [34] | M. Yu, F. Guo, F.P. Tan, N. Li. Dual-targeting nanocarrier system based on CO2-generated thermosensitive liposomes and gold nanorods for cancer thermochemotherapy. J. Control. Release 215(2015)91–100. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.003 |

| [35] | B.S. Pattni, V.V. Chupin, V.P. Torchilin. New developments in liposomal drug delivery. Chem. Rev. 115(2015)10938–10966. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00046 |

| [36] | C.B. Yang, H.M. Wang, D.X. Li, L. Wang. Molecular hydrogels with esterase-like activity. Chin. J. Chem. 31(2013)494–500. DOI:10.1002/cjoc.201300021 |

| [37] | T. Zhang, P. Huang, L.L. Shi, et al., Self-assembled nanoparticles of amphiphilic twin drug from floxuridine and bendamustine for cancer therapy. Mol. Pharm. 12(2015)2328–2336. DOI:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00005 |

| [38] | P.S. Zhang, Y. Huang, F. Zeng, X.T. Xia, S.Z. Wu. A ratiometric two-photon fluorescent probe for detecting carboxylesterase in living cells. Sci. Sin. Chim. (2017)1–8. |

| [39] | P.S. Pramod, N.U. Deshpande, M. Jayakannan. Real-time drug release analysis of enzyme and ph responsive poly-saccharide nanovesicles. J. Phys. Chem. B 119(2015)10511–10523. |

| [40] | S.P. Sanghani, S.K. Quinney, T.B. Fredenburg, et al., Carboxylesterases expressed in human colon tumor tissue and their role in cpt-11 hydrolysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 9(2003)4983–4991. |

| [41] | W. Hakamata, S. Tamura, T. Hirano, T. Nishio. Multicolor imaging of endoplasmic reticulum-located esterase as a prodrug activation enzyme. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 5(2014)321–325. DOI:10.1021/ml400398t |

| [42] | Y.L. Wu, S.L. Huang, F. Zeng, et al., A ratiometric fluorescent system for carboxylesterase detection with AIE dots as FRET donors. Chem. Commun. 51(2015)12791–12794. DOI:10.1039/C5CC04771D |

| [43] | L.W. He, Q.Y. Xu, Y. Liu, et al., Coumarin-based turn-on fluorescence probe for specific detection of glutathione over cysteine and homo-cysteine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7(2015)12809–12813. DOI:10.1021/acsami.5b01934 |

2017, Vol. 28

2017, Vol. 28