b Xinjiang Institute of Materia Medica, Urumqi 830004, China;

c Beijing Key Laboratory of Non-Clinical Drug Metabolism and PK/PD Study, Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100050, China

Glycyrrhetinic acid (GA, 1, Fig. 1), a pentacyclic triterpenoid derivative of the glycyrrhizin, is one of the major constituents of the roots of Glycyrrhiza uralensis which is used in traditional Chinese medicine. Recently, it has been reported that GA exhibits diverse biological properties such as anti-inflammatory, antiulcerative, antiviral, antiallergic, immunomodulating, and antitumour activities [1, 2]. Especially, carbenoxolone, a derivative of GA, has been successfully marked as a licensed medicine for the treatment of esophageal ulceration and inflammation [3]. Thus, the structural modification of GA for more potent agents has attracted much more attention, and numerous progresses has been achieved by microbial transformation [4-8]. Microbial biotransformation is regarded as a powerful approach for the structural modification of natural products with many advantages such as regio-and stereo-selectivity, mild reaction conditions, as well as avoiding complex protection and de-protection steps. Particularly, it can access the reaction that it is difficult to be carried out by chemical approaches [9-12]. Herein, we report the transformation of GA by Cunninghamella blakesleana CGMCC 3.970, the structural elucidation, and neural anti-inflammatory activity of the five new metabolites.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Possible biotransformation pathway of glycyrrhetinic acid (1) by C. blakesleana CGMCC 3.970. | |

2. Results and discussion 2.1. Biotransformation

In this investigation, we aimed at obtaining new bioactive derivatives of GA through microbial transformation approach. TLC and HPLC-UV/MS analysis showed that ten filamentous fungal strains converted GA efficiently (Figs. S1 and S2 in Supporting information). By considering the yields, diversity and novelty of the products, C. blakesleana CGMCC 3.970 was selected for the further scale-up biotransformation investigation.

Following a standard two-stage fermentation protocol [13], GA (1) was incubated with the two-day-old cell cultures of C. blakesleana for seven additional days. Through various chromatography approaches, five new metabolites (2-6, Fig. 1) were isolated. Their structures were elucidated as 15α, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (2, 0.11%), 3-oxo-15α, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (3, 0.75%), 3-oxo-7β, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (4, 0.16%), 3-oxo-7β, 15α, 24-trihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (5, 0.29%), and 3-oxo-7α, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (6, 1.27%) by interpreting various spectroscopic data. These results indicated that C. blakesleana CGMCC 3.970 could catalyze the specific hydroxylation at C-24, C-7, and C-15, and oxidation at C-3. Comparing the chemical structures of substrate (1) and the products (2-6), a plausible bioconversion route was proposed (Fig. 1).

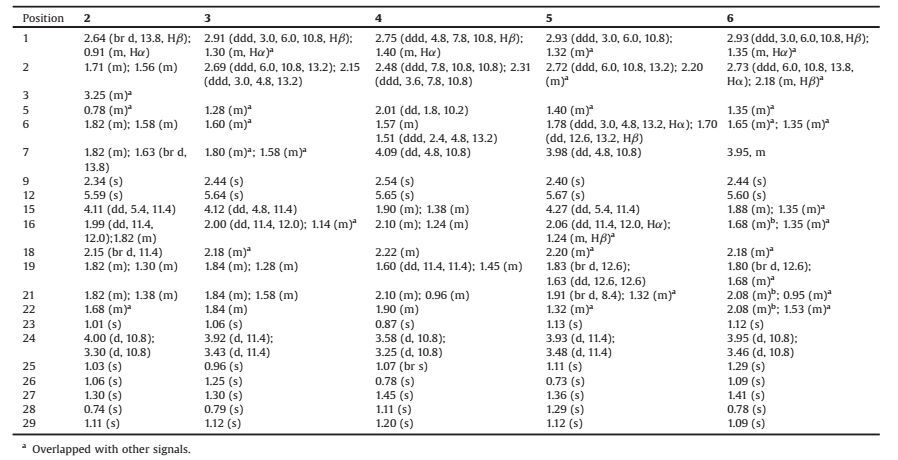

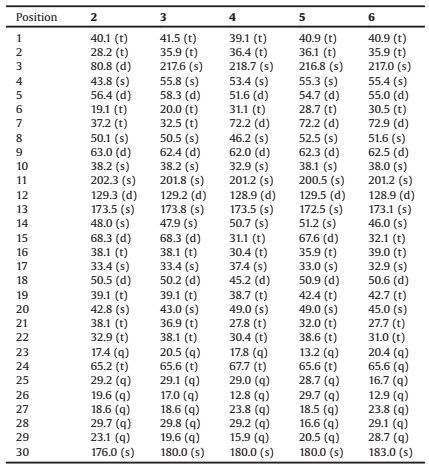

2.2. Structural elucidationThe molecular formula of metabolite 2 was established as C30H46O6 on the basis of HR-ESIMS (m/z 503.3380 [M+H]+, calcd. for C30H47O6, 503.3367). The UV spectrum showed absorption band at 250.5nm. The IR spectrum showed the presence of hydroxyls (3343cm-1) and carbonyl (1644cm-1) groups. The extra 32 mass unit, compared to that of 1, suggested the presence of two additional hydroxy groups. Analysis of the 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data of 2 revealed structural similarity to those of 1 (Tables 1 and 2), except that the appearance of one additional oxygenated methine protonat δH 4.11 (dd, J=5.4, 11.4Hz, H-15) and a hydroxymethyl protons at δH 4.00 (d, J=10.8Hz, H-24a) and 3.30 (d, J=10.8Hz, H-24b). These assignments of the oxygenated methine and hydroxymethyl protons as H-15 and H2-24, respectively, were confirmed by the HMBC correlations of H-15 (δH 4.11)/ C-14, C-16, and C-27; and H2-24 (δH 3.30 and 4.00)/C-3, C-4, and C-23. The relative configuration of H-15 in 2 was determined by its 1D-NOESY spectrum, inwhich the NOESY correlationsof H-15 with H3-26 (δH 1.06) and H3-28 (δH 0.74) indicated their syn-orientation. Besides, in the CD spectrum, the characteristic Cotton effect (CE) of α, β-unsaturated ketone was observed, the configuration at C-9 was determined to be R based on a negative CE at 344 nm (the n-π* transition of the α, β-unsaturated ketone) (Fig. S13 in Supporting information) [14, 15], which is same as that of 1. Therefore, 2 was identified as 15α, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid.

|

|

Table 1 The 1H NMR data of compounds 2–6 (600MHz, J in Hz, CD3OD). |

Compound 3 gave a molecular formula of C30H44O6 by analysis of its HR-ESIMS (m/z 501.3232 [M+H]+, calcd. for C30H45O6, 501.3211). The UV spectrum showed absorption band at 250.5 nm. The IR spectrum showed the presence of hydroxyls (3371 cm-1) and carbonyl groups (1697 and 1645 cm-1). Comparison of the 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopic data (Tables 1 and 2) of 3 with those of 2 revealed a resonance for one more ketone functionality (δC 217.6) and the absence of signal for an oxygenated methine unit (δH 3.25/δC 80.8, C-3), suggesting that the 3-OH in 2 was oxidized to a ketone in 3. The key HMBC correlations of H2-1, H2-2, H2-24, and H3-23/C-3 (δC 217.6) were observed to support this structure as shown in Fig. 1. The NOESY correlation of H-15/H3-28 indicated the syn-orientation of H-15 and H3-28. On the basis of the n-π* transition of the α, β-unsaturated ketone (negative CE at 298 nm, Fig. S24 in Supporting information) [14, 15], the absolute configuration at C-9 was determined to be R. Therefore, the structure of 3 was identified as 3-oxo-15α, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid.

|

|

Table 2 The 13C NMR data of compounds 2–6 (150 MHz, CD3OD). |

Metabolite 4 had the same molecular formula as 3 as determined by the HR-ESIMS peak at m/z 501.3230 [M+H]+ (calcd. for C30H45O6, 501.3211). The UV, IR, 1H, and 13C NMR spectroscopic data of 4 (Tables 1 and 2) displayed the resonances for structural fragments similar to those of 3, except that the oxygenated methine (δC 68.3) was shifted downfiled to δC 72.2 in 4. In addition, C-6 appeared at lower field at δC 31.1 and C-5 was shifted upfield to δC 51.6, displaying the attachment of a hydroxy at C-7 rather than at C-15 in 4. This assignment was further supported by the HMBC correlations of H-7 (δH 4.09)/C-5, C-6, C-8, and C-26. In the NOESY experiment, the enhancement of H-5, H-9, and H3-27 when H-7 was irradiated, indicating the syn-orientation of H-7, H-5, H-9, and H3-27 (Fig. 2). The absolute configuration of C-9 was assigned as 9R according to the n-π* transition of the α, β-unsaturated ketone with a negative CE at 322 nm in the CD spectrum (Fig. S35 in Supporting information). Thus, the structure of 4 was identified as 3-oxo-7β, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Key HMBC (→) and NOESY (↔) correlations of 4. | |

The molecular formula of 5 was determined to be C30H44O7 on the basis of HR-ESIMS analysis (m/z 517.3176 [M+H]+, calcd. for C30H45O7, 517.3160) with 16 amu more than that of 4, indicating the introduction of one additional hydroxy. The UV and IR data were closely identical to those of 2-4. In comparison of the NMR spectroscopic data (Tables 1 and 2) with those of 4, the appearance of an extra oxygenated methine unit [δH 4.27 (dd, 1H, J = 5.4, 11.4 Hz); δC 67.6], which further suggested the introduction of one additional hydroxy group. Furthermore, the HMBC correlations of H-15 (δH 4.27)/C-13, C-14, C-16, and C-17, establising the hydroxylation at C-15. The NOESY correlations of H-15 (δH 4.27)/H3-26, and H3-28; and H-7 (δH 3.98)/H-5, H-9, and H3-27 indicated the anti-orientation of H-15 and H-7. On the basis of CD spectral analysis (Fig. S46 in Supporting information), the structure of 5 was identified as 3-oxo-7β, 15α, 24-trihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid.

Metabolite 6 had the same molecular formula as 4 as determined by the HR-ESIMS peak at m/z 501.3231 [M+H]+ (calcd. for C30H45O6, 501.3211). The general features of its UV, IR, 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data (Tables 1 and 2) closely resembled those of 4 except those for the different chemical shifts for H-5, H-6, H-7, C-5, C-6, and C-8. Analysis of DEPT, 1H-1H COSY, and HMBC correlations suggested that 6 was the stereoisomer of 4. The NOESY correlation of H-7/H3-25 indicated a syn-orientation of H-7 and H3-25. Therefore, the structure of 6 was identified as 3-oxo-7α, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid, a C-7 epimer of compound 4, which was further supported by the CD spectrum with a negative CE at 300 nm (Fig. S57 in Supporting information).

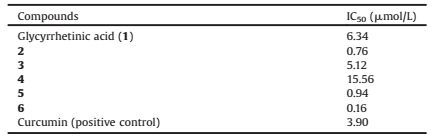

2.3. Anti-inflammatory activityMicroglia are endogenous immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS) that play critical roles in neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson's disease (PD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) [16-18]. The substrate 1 together with the metabolites 2-6 were biologically assayed for their neural antiinflammatory activity using lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced NO production in mouse microglia BV2 cells with curcumin as a positive control. Compounds 2, 5, and 6 exhibited significant inhibition of LPS-induced NO production with IC50 values of 0.76, 0.94, and 0.16 μmol/L, respectively (Table 3), making 2, 5, and 6 much more potent than curcumin (IC50 = 3.9 μmol/L). Thus, compound 2, 5, and 6 might be promising lead compounds for the treatment of PD and AD [18, 19].

|

|

Table 3 Inhibitory activity of compounds 1–6 against lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced NO production in mouse microglia BV2 cells (n = 3). |

3. Conclusion

The microbial transformation of GA by C. blakesleana CGMCC 3.970 was reported and five new metabolites were isolated. It was observed that specific ketonization and hydroxylation were the main reaction types. The 3β-hydroxy group of GA was dehydrogenated into carbonyl group in metabolites 3-6, regio-specific hydroxylation at C-24 in metabolites 2-6, stereo-specific hydroxylation at C-15α in 2, 3, and 5, and selectively hydroxylation at C-7 position. Moreover, compounds 2, 5, and 6 exhibited much more potent neural anti-inflammatory activity than curcumin. These results suggested that biotransformation was a powerful approach for the structural modification of bioactive natural products, and yielding bioactive derivatives with increased potency.

4. Experimental 4.1. GeneralOptical rotations were obtained by a Perking-Elmer Model-343 digital polarimeter. The UV and CD spectra were recorded on a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter. IR spectra were acquired on a Nicolet 5700 FT-IR microscope spectrometer (FTIR Microscope Transmission). 1D and 2D NMR spectra were obtained at 600 MHz for 1H NMR and 150 MHz for 13C NMR on VNOVA SYSTEM-600 spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in ppm, and coupling constants (J) are given in hertz (Hz). HRESIMS were carried out on an Agilent Technologies 6520 Accurate Mass Q-TOF LC/MS spectrometer. Analytical HPLC was performed on an Agilent series 1200 HPLC instrument equipped with a quaternary pump, a diodearray detector (DAD), an autosampler, a column compartment, and a GraceSmart C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, i.d., 5 μm). The mobile phase consisted of ultrapure water and methanol with a two pump gradient program at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min at 30 ℃. Semipreparative reversed-phase HPLC was performed on a Shimadzu HPLC instrument equipped with a Shimadzu RID-10A detector and a Grace Adsorbosphere C18 column (250 mm × 10 mm, i.d., 5 μm) by eluting with mixtures of methanol and H2O at 3.0 mL/min. Silica gel (200-300 mesh, Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co. Ltd., Qingdao, PR China) and Sephadex LH-20 gel (Amersham Biosciences, Sweden) were used for column chromatography (CC). Analytical TLC was carried out on precoated silica gel GF254 plates (Qingdao Marine Chemical Industry, Qingdao, China), and spots were visualized under UV light or by spraying with 10% H2SO4 in EtOH followed by heating at 120 ℃.

4.2. Substrate and organismsThe substrate glycyrrhetinic acid (GA, 1, >97% purity by HPLC) was purchased from J & K Scientific LTD (Beijing, China), and identified by NMR analysis. The ten strains of filamentous fungi (Absidia coerulea CGMCC 3.2462, Alternaria alternata Keissler CGMCC 3.577, Aspergillus niger Van Tieghem CGMCC 3.739, Cunninghamella blakesleana CGMCC 3.970, C. echinulata CGMCC 3.3400, C. elegans CGMCC 3.3402, Mucor javanicus CGMCC 3.193, Penicillium spinulosum CGMCC 3.149, Phyllosticta pirina CGMCC 3.2886, Rhizopus japonicas ZW-4) were purchased from China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC), Beijing, China. The fungal strains were kept on a solid potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium containing potato (200 g/L), glucose (20 g/L), KH2PO4 (3 g/L), anhydrous MgSO4 (0.75 g/L), VB1 (10 mg/ L), and agar (2%) with a pH of 6.0 at 4 ℃. The medium was autoclaved at 121 ℃ for 25 min before use. The seed cultures were prepared in 250 mL flasks with 70 mL liquid medium (without agar) for 2 days of incubation. Avolume of 1 mL of the seed cultures was added to each flask and shaken at 130 r/min and 25 ± 2 ℃ in the dark.

4.3. Preliminary biotransformation screening testPreliminary screening scale transformation was carried out in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 70 mL of PDA liquid medium. After two days of cultivation, 0.1 mL of GA (1, 20 mg/mL, ethanol) was added into each flask. Controls containing medium with substrate and medium with fungus culture were carried out in each case. These flasks were maintained under incubation conditions for four additional days. After removing the mycelium by filtration, the filtrates were extracted three times with equal volume of EtOAc, and the extracts were evaporated in vacuo and analyzed by TLC and HPLC (Figs. S1 and S2 in Supporting information).

4.4. Preparative biotransformationThe preparative scale microbial transformation of 1 by C. blakesleana CGMCC 3.970 was carried out in 100 Erlenmeyer flasks (1 L) containing 300 mL of PDA medium. After two days of incubation, 1 (3.0 g in 10.8 mL ethanol) was evenly distributed into each flask and incubated for seven additional days. After which time, the mycelia were removed by filtration, the filtrate was applied to a Amberlite XAD-16 macroporous adsorbent resin column by eluting with H2O, 50% EtOH, 75% EtOH, and 100% EtOH, successively. The residue of 50% EtOH and 75% EtOH fraction were concluded to contain the main metabolites by TLC analysis. Then these fractionswere combinedtogive1.9 g residue. The residuewas subjected onto a silica gel chromatography column and eluted with petroleum ether (60-90 ℃)-Acetone (in a gradient manner from 5:1 to Acetone) to afford 8 fractions (Fr.1-Fr.8). Based on the results of TLC and HPLC analyses, the metabolites of 1 were detected in Fr.4 and Fr.6. Then these fractions Fr.4 (234.0 mg) and Fr.6 (390.8 mg) were further purified by reversed phase semipreparative HPLC, yielding metabolites 2 (4.2 mg, 40% MeOH, tR = 21.0 min, 0.11% yield), 3 (26.1 mg, 40% MeOH, tR = 17.9 min, 0.75% yield), 4 (4.9 mg, 45% MeOH, tR = 72.2 min, 0.16% yield), 5 (8.7 mg, 45% MeOH, tR = 77.4 min, 0.29% yield), and 6 (38.1 mg, 45% MeOH, tR = 77.4 min, 1.27% yield). The pH value of semipreparative reversed HPLC phase was adjusted to 3.1.

15α, 24-Dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (2). White amorphous powders. [α]D 20+77.8 (c 0.094, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 250.5 (4.06) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε) 217 (5.49), 245 (4.17), 344 (-0.13) nm; IR (vmax) 3343, 2957, 2928, 1644, 1568 cm-1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2; HR-ESIMS m/z: 503.3380 [M+H]+ (calcd. for C30H47O6, 503.3367).

3-Oxo-15α, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (3). White amorphous powders. [α]D 20 +94.9 (c 0.052, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 250.5 (3.75) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε) 215 (4.82), 247 (4.13), 298 (-0.28) nm; IR (vmax) 3371, 2928, 2868, 1697, 1645, 1568 cm-1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2; HR-ESIMS m/z: 501.3232 [M+H]+ (calcd. for C30H45O6, 501.3211).

3-Oxo-7β, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (4). White amorphous powders. [α]D 20 +111.9 (c 0.052, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 250.5 (4.10) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε) 230 (16.04), 322 (-0.55) nm; IR (vmax) 3393, 2954, 2932, 2870, 1696, 1650, 1558 cm-1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2; HR-ESIMS m/z: 501.3230 [M+H]+ (calcd. for C30H45O6, 501.3211).

3-Oxo-7β, 15α, 24-trihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (5). White amorphous powders. [α]D 20 +120.4 (c 0.152, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 249.5 (3.94) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε) 221 (10.45), 300 (-0.74) nm; IR (vmax) 3364, 2959, 2873, 1701, 1660 cm-1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2; HR-ESIMS m/z: 517.3176 [M +H]+ (calcd. for C30H45O7, 517.3160).

3-Oxo-7α, 24-dihydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (6). White amorphous powders. [α]D 20 + 114.0 (c 0.061, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 249.0 (4.10) nm; CD (MeOH) λmax (Δε) 231 (17.31), 300 (-0.83) nm; IR (vmax) 3434, 2955, 2872, 1701, 1656 cm-1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Tables 1 and 2; HR-ESIMS m/z: 501.3231 [M+H]+ (calcd. for C30H45O6, 501.3211).

4.5. Anti-inflammatory activity assay [20, 21]The BV2 microglia cell line was obtained from the Cell Culture Center at the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. lipopolysaccharide (LPS, from Escherichia coli 055:B5) was offered by Sigma-Aldrich. After preincubation for 24 h in a 96-well plate (at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2), the cells were treated with various concentrations of the test compounds (10-5, 10-6, 10-7, and 10-8 mol/L), followed by stimulation with LPS for 24 h. The production of NO was determined by measuring the concentration of nitrite in the culture supernatant. NaNO2 was utilized to generate a standard curve. The absorbance at 550 nm was measured. Curcumin was used as a positive control.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2017.02.019.

| [1] | M.H. Salari, S. Eshraghi, M. Noroozi. Antibacterial effect of glycyrrhetinic acid on 55 hospital strains of Staphylococcus aureus and 32 Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 9(2001)37–39. |

| [2] | D. Maitraie, C.F. Hung, H.Y. Tu, et al., Synthesis, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives as chemical mediators and xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17(2009)2786–2792. |

| [3] | E.A. Davis, D.J. Morris. Medicinal uses of licorice through the millennia:the good and plenty of it. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 78(1991)1–6. DOI:10.1016/0303-7207(91)90179-V |

| [4] | D.H. Kim, S.W. Hong, B.T. Kim, et al., Biotransformation of glycyrrhizin by human intestinal bacteria and its relation to biological activities. Arch. Pharm. Res. 23(2000)172–177. DOI:10.1007/BF02975509 |

| [5] | G.T. Matooq, A.M. Marzouk, A.I. Gray, et al., Bioactive microbial metabolites from glycyrrhetinic acid. Phytochemistry 71(2010)262–270. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.09.014 |

| [6] | X.L. Xin, Y.F. Liu, M. Ye, et al., Microbial transformation of glycyrrhetinic acid by Mucor polymorphosporus. Planta Med. 72(2006)156–161. DOI:10.1055/s-2005-873198 |

| [7] | Amin H.A. Salam, H.A. El-Menoufy, A.A. El-Mehalawy, et al., Biosynthesis of glycyrrhetinic acid 3-O-mono-β-D-glucuronide by free and immobilized Aspergillus terreus β-D-glucuronidase. J. Mol. Catal. B:Enzym 69(2011)54–59. DOI:10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.12.010 |

| [8] | Y.J. Qin, B. Feng, X.B. Song, et al., Biotransformation of glycyrrhetinic acid by Cunninghamella blakesleeana. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 8(2010)373–381. |

| [9] | A. Giri, V. Dhingra, C.C. Giri, et al., Biortansformations using plant cells, organ cultures and enzyme systems:current trends and future prospects. Biotechnol. Adv. 19(2001)175–199. DOI:10.1016/S0734-9750(01)00054-4 |

| [10] | L.R. Qiao, D. Xie, Q. Liu, et al., Microbial transformation of lovastatin by Beauveria bassiana. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2(2012)300–305. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2012.04.001 |

| [11] | X. Liu, D. Xie, R. Chen, et al., A furantaxane with an unusual 6/8/6/5 ring system and potent tumor MDR reversal activity obtained via microbial transformation. Org. Lett. 14(2012)4106–4109. DOI:10.1021/ol301755n |

| [12] | L. Yang, Z. Wang, H. Lei, et al., Neuroprotective glucosides of magnolol and honokiol from microbial-specific glycosylation. Tetrahedron 70(2014)8244–8251. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2014.09.033 |

| [13] | X. Liu, R. Chen, D. Xie, et al., Microbial transformations of taxadienes and the multi-drug resistant tumor reversal activities of the metabolites. Tetrahedron 68(2012)9539–9549. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2012.09.091 |

| [14] | G. Snatzke. Circulardichroismus-IX:modifizierung der octantenregel für α, β-ungesättigte ketone:transoide enone. Tetrahedron 21(1965)421–438. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)98283-3 |

| [15] | D.N. Kirk. The chiroptical properties of carbonyl compounds, the chiroptical properties of carbonyl compounds. Tetrahedron 42(1986)777–818. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87486-X |

| [16] | H.Y. Kim, E.J. Park, E. Joe, et al., Curcumin suppresses Janus kinase-STAT inflammatory signaling through activation of Src homology 2 domaincontaining tyrosine phosphatase 2 in brain microglia. J. Immunol. 171(2003)6072–6079. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6072 |

| [17] | S. Yang, D. Zhang, Z. Yang, et al., Curcumin protects dopaminergic neuron against LPS induced neurotoxicity in primary rat neuron/glia culture. Neurochem. Res. 33(2008)2044–2053. DOI:10.1007/s11064-008-9675-z |

| [18] | C. Schwab, A. Klegeris, P.L. McGeer. Inflammation in transgenic mouse models of neurodegenerative disorders. BBA:Mol. Basis Dis. 1802(2010)889–902. DOI:10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.10.013 |

| [19] | S. Sugama, T. Takenouchi, B.P. Cho, et al., Possible roles of microglial cells for neurotoxicity in clinical neurodegenerative diseases and experimental animal models. Inflamm. Allergy:Drug Targets 8(2009)277–284. DOI:10.2174/187152809789352249 |

| [20] | H.M. Shin, B.H. Kim, E.Y. Chung, et al., Suppressive effect of novel aromatic diamine compound on nuclear factor-kB-dependent expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 521(2005)1–8. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.07.013 |

| [21] | H.Y. Pang, G. Liu, G.T. Liu. Compound FLZ inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory effects via down-regulation of the TAK-IKK and TAK-JNK/p38MAPK pathways in RAW264.7 macrophages. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 30(2009)209–218. DOI:10.1038/aps.2008.29 |

2017, Vol. 28

2017, Vol. 28