b Key Laboratory for Biomechanics and Mechanobiology of the Ministry of Education, School of Biological Science and Medical Engineering, Beihang University, Beijing 100191, China;

c Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China;

d College of Physical Science and Technology, Research Institute for Biomimetics and Soft Matter, Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory for Soft Functional Materials Research, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, China

Learning from nature provides us with various inspirations for developing useful medical devices for human illness, and solving problems relating to energy efficiency and food security [1]. By observing the behaviors of natural creatures, we can get new ideas to prepare the advanced medical devices. For instance, jellyfish, whose movement of body is powered by its body-fluid, is a unique case for a muscular pump in tissue engineering [2]; octopus' arm, is a stimulation for the design of a soft manipulator for minimally invasive surgery [3]; elephant trunk, squid tentacle, and snake have set a model for the development of robotic devices [4]; footpads of gecko, have been considered as a case for the designing of polymers in tissues [5], etc. Currently, bioinspired approaches have been widely used for therapeutic goals. For example, the bioinspired cage nanoparticles have been developed for drug deliveries [6]; inspired by sandcastle worms, a nanoparticulate formulation from a viscous poly(glycerol sebacate)-acrylate is designed to replace the sutures and staples for minimally invasive tissue repair [7]; the biomimetic interfaces, which are equivalent to the natural extracellular matrix, are introduced for bone injury repair based on the surface chemistry modification or the built up of nanostructures or microstructures of implantable materials [8]; the bioinspired mechatronic face with skin, eyes and neck mimicking human-like performance is developed as an intelligent device for medical students hands-on learning experience [9]; and the biomimetic materials have been designed for the cardiac tissue regeneration including injection of materials for stimulation of endogenous repair, implantation of cardiac patches, injection of cells and valve replacement [10]. Among all the medical devices, the cardiac devices are one of the most important and representative types [11]. Cardiovascular disease has become the leading cause of death worldwide [11]. The annual cost of heart disease in United States is estimated to be 215.6 billion dollars, which accounts for almost two-thirds of the total of cardiovascular disease and stroke, and equals to the total costs of cancer and benign neoplasms [11]. Here, we will take the cardiac medical device as the example to show how the bioinspired approaches are applied for solving the medical problems.

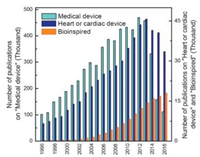

2. Recent bioinspired researches on medical devicesDuring the last two decades, the number of academic researches on both medical devices and bioinspired studies has been increasing tremendously, as indicated in Fig. 1. The publications on bioinspired studies increase exponentially in the past 20 years, which demonstrates that bioinspired researches have attracted great attentions. In contrast, the publications on medical devices and cardiac devices increase steadily from the year 1996 to 2012, but the number of publications starts to decrease from 2013, which indicates that some bottlenecks might exist in the development of medical devices and cardiac devices. Typical cardiac medical devices have been developed recently, including synthetic vascular grafts, electronic pacemakers, coronary stents, mechanical heart valves and left ventricular assist devices, as illustrated in Fig. 2a-e. However, there are many issues in these devices. For instance, the acute thrombosis and intimal hyperplasia exist in the synthetic vascular grafts (Fig. 2a); the infections, pacing-induced remodeling, and autonomic responsiveness are associated with electronic pacemakers (Fig. 2b); the restenosis, late thrombosis and mechanics are the problems in coronary stents (Fig. 2c); and the thrombosis and mechanics happen both for the mechanical heart valves (Fig. 2d) and left ventricular assist devices (Fig. 2e). Overall, it is still a challenging task to achieve the following goals: reducing and avoiding the thrombosis formation, obtaining excellent performance and achieving stable electronic physiology. We believe that bioinspired approaches could provide an alternative to make medical devices with various complicated optimal properties and enhance their functionality for clinical applications. The following parts are mainly based on the bioinspired approaches to prevent thrombosis, improve mechanical performance and enhance the electronic physiology.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Publications related to medical devices, heart or cardiac device and bioinspired studies from 1996 to 2016. The data were collected from http://scholar. google.com/ with searching date 2017/02/10, and the key words were "Medical device", "Heart or cardiac device" and "Bioinspired", respectively. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Typical cardiac medical devices and their main clinical issues. (a) Synthetic vascular grafts with the issues of acute thrombosis and intimal hyperplasia. (b) Electronic pace makers with the issues of infections, pacing-induced remodeling and autonomic responsiveness. (c) Coronary stents with the issues of restenosis, late thrombosis and mechanics. (d) Mechanical heart valves with the issues of thrombosis and mechanics. (e) Left ventricular assist devices with the same issues as mechanical heart valves. | |

3. Bioinspired approaches for medical devices 3.1. Bioinspired approaches to prevent thrombosis

Thrombosis forms when fibrin and platelets adhere to the surface of the synthetic vascular grafts during the flowing of blood (Fig. 2a, c and d). Biomaterial surface coatings have been applied for suppressing the formation of blood clots, heparin coating, PHISIO (Sorin) coating, sulfobetaine coating, trillium (Medtronic) coating, and poly-2-methoxyethyl acrylate (PMEA) polymer coating. Among these surface coatings, heparin-coating is the most successful approach [12]. However, these strategies are limited for reducing thrombosis of extracorporeal circuits. Here, we would introduce three approaches to prevent thrombosis: 1) providing a liquid-infused porous surface as a surface coating for the medical devices, 2) infusing a functional gating liquid into the membrane in the devices, 3) designing a liquid-repellent gas membrane for the medical devices.

One approach to address the clots issue is creating a slippery, liquid-infused, porous surface (SLIPS), which is inspired by the Nepenthes pitcher plant [12]. Like the Nepenthes pitcher plant that can prevent the attachment of insects by using a layer of liquid to create a low friction surface, the SLIPS can prevent the adhesion to underlying substrate by a formation of a stable immobilized liquid overlayer. The SLIPS is achieved by infiltrating various liquid perfluorocarbons into porous or roughened surfaces. The nonadhesive, antithrombogenic surfaces are accomplished by coating a tethered perfluorocarbon layer with a mobile layer of perfluorodecalin (referred as TLP surface) on medical-grade polycarbonate, polyvinyl chloride and polysulfone substrates. The TLP surface coating effectively resists the adhesion of blood components and bacteria, repels whole blood and prevents thrombosis both in vitro and in vivo without dangerous anticoagulants. Especially, TLPcoated arteriovenous shunt retained the ability to avoid occlusive thrombus formation up to more than 8 h when implanted in pigs [12]. The advantage of the TLP coating is that it depends on a lowpressure plasma surface modification, which is commonly applied for commercial modification of materials. Moreover, this can be used for the materials with complex geometry, without changing their bulk properties.

A second approach is to introduce the bioinspired liquid-based gating mechanism, which mimics the micro-/nanometer-sized pore in living organism, as gatekeepers for coordinating multiphase transport without clogging [13-16]. The liquid gating mechanism uses a capillary-stabilized liquid as a reconfigurable gate and exhibits a non-fouling property. The liquid lining prevents fouling in nano-and micro-pores as well as microfluidic channels. It shows no retention of fluorescent protein or blood, which provides a new opportunity to develop biomedical fluid devices for anti-thrombosis applications. This liquid gating system could be created by using varieties of porous materials and a broad range of gating liquids. Nevertheless, the achievement of anti-fouling property should be based on three criteria: 1) the gating liquid should be wet and adhesive to the membrane, 2) the membrane has a higher affinity to the gating liquid than to the transport substance, i.e., the interfacial energy between the membrane and the gating liquid should be lower than that between the membrane and the transport substance, 3) the gating liquid should be immiscible with the transport substance.

In the third approach, a super liquid-repellent gas membrane is designed for anti-thrombosis [17]. This method employs superamphiphobic membranes to exchange carbon dioxide. The superamphiphobic layer is comprised of a network of fluorinated silicon oxide nanoparticles. The trapped gas between the nanoparticles prevents the liquid from contacting the membrane. It is demonstrated that the superamphiphobic membrane works well to capture the carbon dioxide gas into an aqueous solution and to oxygenate blood without clogging on the membrane for up to 24 h [17]. The mechanism relies on that the superamphiphobic layer contains microscopic protrusions with overhanging topography and the protrusions are fluorinated to create surface hydrophobic. The liquid on top of this kind of layer would be separated from the liquid by the trapped air, due to the small solid/liquid contact area on top of the protrusions. The potential applications of this liquidrepellent gas membrane would be extracorporeal membrane oxygenators in heart-lung machines.

3.2. Bioinspired approaches to improve mechanical performanceBesides the thrombosis, current cardiac devices are still encountered by mechanical issues, such as, hemodynamics in coronary artery and heart, and solid mechanics in cardiac tissue (Fig. 2c and d). Bioinspired approaches have been used to address these problems. For instance, the inspiration of helical flow in the arterial system [18], the biomimetic soft sleeve designed to assist heart movement [19], the bioinspired method to reduce the left ventricular workload [20], and the biomimetic glue to repair vessels and heart defects [21], etc. Helical flow is considered as the rotational motion of blood normal to the mainstream of blood flow path during the passage of artery [18]. Recent studies show that helical flow might play vital roles in suppressing disturbed blood flow, avoiding the accumulation of atherogenic low density lipoproteins and limiting the adhesion of blood cells on the surface of arteries, facilitating blood flow transport and boosting oxygen transport from blood to the arterial wall [18, 22]. The researches have been probed into the possibility to use helical flow for the design of vascular interventions, aiming to prevent intimal hyperplasia and thrombus formation due to abnormal flow conditions. A bioinspired soft actuator based on the mechanical properties of tissue was made from contractile elements embedded in an elastomeric matrix [19]. By designing the structure of the actuator and varying the matrix materials, different freedom of activation could be achieved. One case is that a designed actuator could mimic the orientations of fiber in the heart. This inspiration prompts huge potential applications, ranging from replacing or restoring the functions of failing organs to stimulating normal physiological and pathological motions. Similarly, a bioinspired method to intimate the mammalian arterial wave reflection was established to reduce the left ventricular work load in heart failure patients [20]. It simply places a ring around the aorta to change the wave dynamic. This approach could pave a way for the future treatments of diseased aorta. Another case is a bioinspired elastic and biocompatible hydrophobic light-activated adhesive (HLAA), which is used for minimally invasive repair of heart defects and vessels [21]. It is based on the concept of viscous secretions of sandcastle worms and insect footpads that contain waterimmiscible components in aqueous environments. Upon seconds of light activation, the HLAA works as an on-demand hemostatic seal when applied to high-pressure blood vessels and cardiac wall effects in pigs. It could stay in the interventricular septum in a beating porcine heart for 24 h [21]. This material may be potentially used in cardiovascular and surgical applications, such as, repair of vascular defects and surgical hemostasis. In summary, the mechanical issues of cardiac devices find promising solutions with the help of bioinspired approaches.

3.3. Bioinspired approaches to enhance electronic physiologyElectronic pacemaker is a big branch of cardiac medical devices. Currently, the problems associated with the electronic pacemakers are infections, pacing-induced remodeling, lack of autonomic responsiveness, interference with other devices, lead fracture and extraction, and so on [23]. The automaticity of a healthy heart is a property of sinoatrial node (SAN). Meanwhile, it could also be triggered by specialized conducting fibers with intrinsic automatic rates lower than those of SAN. Both of the cardiac muscle and specialized conducting tissues can be excited in response to electrical or mechanical stimulations [23]. The key issues of the pacemaker are the current and "Ca2+ clock" mechanism. Regarding the clock, the ion channels and the inward and outward currents are regulated by cyclic nucleotides, G proteins, or other contributors. The net current between inward and outward currents and the exchangers govern the eventual pacemaker rate. There are Na+/ Ca2+ exchangers in SAN and Na+/K+ pumps in the secondary pacemakers. One approach to figure out the issues in a pacemaker is through the design of a biological pacemaker. The biological pacemaker is comprised of: an initiator, a cell or cells with pacemaker functions by incorporating or modifying a gene or genes; a substrate, to which the signal is delivered and then convey it to the conducting system; and the connectivity among trigger cells, among substrate cells and between triggers and substrate cells [23]. Another approach for the electronic pacemaker, is the design of bioinspired ion channels. The ion channel could be made of biocompatible polymers and then modified by immobilizing Gquadruplex DNA, which undergoes a conformation change upon the potassium concentration and then induces the change of channel size and thus the current through the channel [24]. Likewise, the bioinspired ion channel has been reported as a tunable mercury (Ⅱ) ion gate, where the potassium ion can reversibly switch to "on" and "off" state in the absence and presence of mercury ions [25]. DNA-modified polymer nanopores were able to simultaneously respond to pH and voltage change [26]. These biomimetic ion channels could spark the development of ion transport in the electronic pacemakers for in vivo applications. Next approach is the development of bioinspired pacemaker. A muscular pump is designed based on the propulsion inspiration of jellyfishes [2]. The electrically synchronized myofibrils could match key determinants of jellyfish propulsion and the feeding performance. This strategy shines a light on the design of biomimetic pacemakers or other muscular organs.

4. Conclusions and prospectIn this perspective, bioinspired approaches for medical applications are demonstrated by tracking the biomimetic methods applied in cardiac medical devices. Through themagnifying lens, bioinspired approaches have provided promising solutions for solving the therapeutic problems. However, roadblocks encountered with bioinspired pathways for the current medical devices are how to ensure the bioinspired materials in those devices to create artificial, biocompatible interfaces that can direct or coordinate with the functions of biological cells, mimicking the physical properties and chemical properties of biological surfaces [5]. The materials with active biological functions that can sense or stimulate the elements of local immune system would be a subject of future work. For example, supramolecular hydrogel has been used to mimic the extracellular matrix [5, 27, 28]. The unifying theme is to tackle the thrombogenic, mechanical and electronic physiology problems, and ensure a biocompatible medical device with promising longevity and sustainable functionality. There is no doubt that it will take a broad range of teamwork in the fields of bioinspired materials, physical chemistry, biotechnology, medical devices, medicines, and clinics to push forward both the fundamental science and the therapeutic development of materials. We hope this perspective will attract the interestof scholarsin these areas to contribute to the developmentof bioinspired medical devices for the welfare of mankind.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21673197, 31570947), Young Overseas High-level Talents Introduction Plan, the 111 Project (No. B16029), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (No. 20720170050).

| [1] | S. Emilie. Interdisciplinarity:bring biologists into biomimetics. Nature 529(2016)277–278. DOI:10.1038/529277a |

| [2] | J.C. Nawroth, H. Lee, A.W. Feinberg, et al., A tissue-engineered jellyfish with biomimetic propulsion. Nat. Biotechnol. 30(2012)792–797. DOI:10.1038/nbt.2269 |

| [3] | T. Ranzani, G. Gerboni, M. Cianchetti, A. Menciassi. A bioinspired soft manipulator for minimally invasive surgery. Bioinspir. Biomim. 10(2015)1–14. |

| [4] | D. Trivedi, C.D. Rahn, W.M. Kier, I.D. Walker. Soft robotics:biological inspiration. state of the art, and future research, Appl. Bionics. Biomech. 5(2008)99–117. DOI:10.1155/2008/520417 |

| [5] | J.J. Green, J.H. Elisseeff. Mimicking biological functionality with polymers for biomedical applications. Nature 540(2016)386–394. DOI:10.1038/nature21005 |

| [6] | S. Deshayes, R. Gref. Synthetic and bioinspired cage nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nanomedicine 9(2014)1545–1564. DOI:10.2217/nnm.14.67 |

| [7] | Y. Lee, C. Xu, M. Sebastin, et al., Bioinspired nanoparticulate medical glues for minimally invasive tissue repair. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 4(2015)2587–2596. DOI:10.1002/adhm.201500419 |

| [8] | A. Bruinink, M. Bitar, M. Pleskova, et al., Addition of nanoscaled bioinspired surface features:a revolution for bone related implants and scaffolds?. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 102(2014)275–294. DOI:10.1002/jbm.a.34691 |

| [9] | E. Baldrighi, N. Thayer, M. Stevens, S.R. Echols, S. Priya. Design and implementation of the bio-inspired facial expressions for medical mannequin. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 6(2014)555–574. DOI:10.1007/s12369-014-0240-4 |

| [10] | D.A. Dunn, A.J. Hodge, E.A. Lipke. Biomimetic materials design for cardiac tissue regeneration. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.:Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 6(2014)15–39. DOI:10.1002/wnan.2014.6.issue-1 |

| [11] | D. Mozaffarian, E.J. Benjamin, A.S. Go, et al., Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update. Circulation 131(2015)e29–e322. DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152 |

| [12] | D.C. Leslie, A. Waterhouse, J.B. Berthet, et al., A bioinspired omniphobic surface coating on medical devices prevents thrombosis and biofouling. Nat. Biotechnol. 32(2014)1134–1140. DOI:10.1038/nbt.3020 |

| [13] | X. Hou, Y. Hu, A. Grinthal, M. Khan, J. Aizenberg. Liquid-based gating mechanism with tunable multiphase selectivity and antifouling behaviour. Nature 519(2015)70–73. DOI:10.1038/nature14253 |

| [14] | X. Hou. Smart gating multi-scale pore/channel-based membranes. Adv. Mater. 28(2016)7049–7064. DOI:10.1002/adma.201600797 |

| [15] | L. Min, S. Chen, Z. Sheng, et al., Development and application of bio-inspired and biomimetic microfluidics. Acta Phys. Sin. 65(2016)153–168. |

| [16] | X. Hou, Y.S. Zhang, G.T.-d. Santiago, et al., Interplay between materials and microfluidics, Nat. Rev. Mater. (2017), doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2017.16. |

| [17] | M. Paven, P. Papadopoulos, S. Schöttler, et al., Super liquid-repellent gas membranes for carbon dioxide capture and heart-lung machines. Nat. Commun. 4(2013)1–6. |

| [18] | X. Liu, A. Sun, Y. Fan, X. Deng. Physiological significance of helical flow in the arterial system and its potential clinical applications. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 43(2015)3–15. DOI:10.1007/s10439-014-1097-2 |

| [19] | E.T. Roche, R. Wohlfarth, J.T.B. Overvelde. Overvelde T.B.. et al. A bioinspired soft actuated material, Adv. Mater. 26(2014)1200–1206. |

| [20] | N.M. Pahlevan, M. Gharib. A bio-inspired approach for the reduction of left ventricular workload. PLOS ONE 9(2014)1–12. |

| [21] | N. Lang, M.J. Pereira, Y. Lee, et al., A blood-resistant surgical glue for minimally invasive repair of vessels and heart defects. Sci. Transl. Med. 6(2014)1–10. |

| [22] | X. Liu, L. Wang, Z. Wang, et al., Bioinspired helical graft with taper to enhance helical flow. J. Biomech. 49(2016)3643–3650. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.09.028 |

| [23] | M.R. Rosen, R.B. Robinson, P.R. Brink, I.S. Cohen. The road to biological pacing. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 8(2011)656–666. DOI:10.1038/nrcardio.2011.120 |

| [24] | X. Hou, W. Guo, F. Xia, et al., A biomimetic potassium responsive nanochannel:G-quadruplex DNA conformational switching in a synthetic nanopore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(2009)7800–7805. DOI:10.1021/ja901574c |

| [25] |

F. Zhang, J. Ma, Y. Sun, et al.,

Fabrication of a mercaptoacetic acid pillar[ |

| [26] | S.F. Buchsbaum, G. Nguyen, S. Howorka, Z.S. Siwy. DNA-modified polymer pores allow pH-and voltage-gated control of channel flux. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(2014)9902–9905. DOI:10.1021/ja505302q |

| [27] | G.F. Liu, D. Zhang, C.L. Feng. Control of three-dimensional cell adhesion by the chirality of nanofibers in hydrogels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53(2014)7789–7793. DOI:10.1002/anie.201403249 |

| [28] | C.L. Feng, X. Dou, D. Zhang, H. Schönherr. A highly efficient self-assembly of responsive C2-cyclohexane-derived gelators. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 33(2012)1535–1541. DOI:10.1002/marc.201200274 |

2017, Vol. 28

2017, Vol. 28