b Department of Inorganic and Physical Chemistry, COMOC-Center for Ordered Materials, Organometallics and Catalysis, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281-S3, 9000 Ghent, Belgium;

c Liaoning Key Laboratory of Petrochemical Technology and Equipments, Dalian 116024, China;

d Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Dalian 116023, China

Propylene oxide (PO) is an important chemical feedstock, and usually is commonly produced by the chlorohydrin and the hydroperoxide method in industry [1]. Numerous studies have been focused on developing new catalytic systems for the liquid phase epoxidation of propylene [2-7]. For instance, Ivanov et al. synthesized a polymer catalyst based on an Amberlite IRA-45 anion-exchange resin modified with molybdenum hexacarbonyl. Its catalytic performance in the epoxidation of propylene with TBHP is comparable with the homogeneous catalyst Mo(CO)6 [3]. Miao et al. found that MoO3/SiO2 is an effective catalyst for the liquid phase epoxidation of propylene. The small size (below 5 nm) of β-MoO3 and monomeric molybdenum species resulted in an increase in the catalytic performance. At 80 ℃ and 2.2 MPa for 4 h, the conversion of CHP and the selectivity to PO can reach > 99% and 85.3%, respectively [5]. They observed that the weak Lewis acidic sites are the active sites, and that the total amount of Lewis acid sites on the catalyst surface is related to the CHP conversion. MoO3/SiO2 prepared with precipitant of pH 9 exhibits the highest selectivity to PO (91.5%) [8]. A Mo-containing silica meso-cellular foam (Mo-MCF) material was used to catalyze the epoxidation of propylene with CHP, the results have showed that, isolated and poly-molybdenum species are responsible for the increase of the epoxidation selectivity [9]. It should be noted that, in the industrial CHP process, the byproduct α, α-dimethyl benzyl alcohol can be converted into CHP by dehydration, hydrogenation and oxidation reactions, thus forms an recyclable process for the utilization of the oxidant.

In recent years, Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have shown great potential as heterogeneous catalysts, due to their large surface area, tunability of the pore size and surface functional group, as well as shape-and size-selectivity [10-16]. MOFs containing Mn, Cu, Cr, Co, Mo, and Ti etc. have already shown good catalytic performance in the epoxidation of alkenes when using O2 or organic hydroperoxide as the oxidant [17-22]. Although the CHP process is a recyclable process, up to now, MOFs have not been examined in the epoxidation of propylene using CHP as oxidant. In this work, two MOFs were synthesized and used as catalytic support. The catalytic active Mo species were embedded into both frameworks via two different synthetic approaches. One catalyst, denoted as Mo@COMOC-4, in which a MoO2Cl2 complex is anchored onto the bipyridine sites of the framework (COMOC-4 = Ga(OH)(OOC-C12N2H6-COO) by a post synthetic modification approach. With the strong affinity between MoO2Cl2 complex and bipyridine sites, this catalyst is expected to have good regeneration property. The other catalyst is PMA@MIL-101(Cr) which has a zeotypic MTN framework (MIL-101(Cr) = Cr3(OH)(H2O)2(μ3-O)(OOC-C6H4-COO)3), in which a Keggin-type polyoxometalate (phosphomolybdic acid, H3PMo12O40, denoted as PMA) was incorporated into the cages via. a ship-in-bottle approach. Moreover, MoO3@SiO2 was prepared as a stardard supported catalyst, the catalytic performance and regenerability of Mo@COMOC-4 and MoO3@SiO2 were compared in the propylene epoxidation reaction.

2. Results and discussion 2.1. Characterization of the Mo containing MOFsIn this study, two types of MOF materials were selected and examined for their catalytic performance in the epoxidation of propylene. Firstly, COMOC-4, which is isostructural to MOF-253, is a gallium based 2, 2'-bipyridine-5, 5'-dicarboxylate framework with one dimensional microporous channels. From our previous study it was seen that this framework is stable in air and water (50 ℃ for 24 h) [21]. Moreover from this study it was noted that the MoO2Cl2 has a strong binding affinity toward the bipyridine sites, as no leaching of the Mo species was observed during the epoxidation of cycloalkenes using Mo@COMOC-4 as catalyst. Secondly, PMA@-MIL-101(Cr) has been synthesized following a well-documented procedure [23]. In Fig. 1, the XRD patterns of Mo@COMOC-4 and PMA@MIL-101 are depicted before and after catalysis. As can be seen from this figure and reports [23], the modified MOFs exhibit the same XRD pattern as the parent MOFs, except for some slight decrease of intensity of the reflections.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 1. XRD patterns of (a) Mo@COMOC-4 and (b) PMA@MIL-101 before and after catalysis. | |

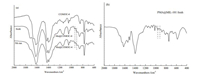

The FT-IR spectra of Mo@COMOC-4 and PMA@MIL-101 before and after catalysis are shown in Fig. 2. The FT-IR spectrum of Mo@COMOC-4 shows vibrations in the region 1542-1624 cm-1 and 1394-1425 cm-1 which can be attributed respectively to the asymmetric and symmetric —COO stretching vibrations of the carboxylate ligands of the parent MOF materials. Additionally, Mo@COMOC-4 has two vibrations at 910 cm-1 and 947 cm-1, which can be assigned to the νsym(Mo=O) and νasym(Mo=O) vibrations of the Mo complex. The FT-IR spectrum of PMA@MIL-101(Cr) contains the typical bands of the Keggin-type PMo12, with νasym(PO4) at 1063 cm-1, νasym(Mo=O) at 958 cm-1 and νasym(Mo=O) at 915 cm-1 in addition to those expected for unfunctionalized MIL-101 structure.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 2. FT-IR spectra of (a) Mo@COMOC-4 and (b) PMA@MIL-101 before and after catalysis. | |

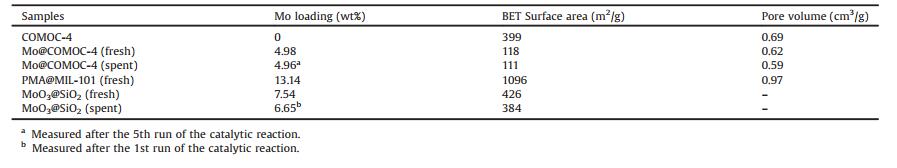

The XRD and FT-IR measurements confirmed the successful incorporation of the Mo complex and Mo-polyoxometalate in the MOF host materials without changing the main structure of the parent framework [21, 23]. It is shown in Table 1, COMOC-4 exhibits a BET surface area of 399 m2/g and a pore volume of 0.69 m3/g. After the post-modification, the Mo@COMOC-4 shows a reduced BET surface area of 118 m2/g, and the pore volume reduced to 0.62 m3/g. After 5 runs of catalytic reaction, the BET surface area and pore volume for Mo@COMOC-4 decreased to 111 m2/g and 0.59 m3/g, respectively. The Mo loading are 4.98 wt% and 13.14 wt % for Mo@COMOC-4 and PMA@MIL-101 before catalysis respectively. The MoO3@SiO2 catalyst shows a Mo loading of 7.54 wt% and a surface area of 426 m2/g. The thermal stability of Mo@COMOC-4 in comparison with the parent COMOC-4 material has been examined (Fig. S1 in Supporting information). From this figure, one can clearly see that the thermal stability of the Mo@COMOC-4 is only slightly reduced. They are both thermally stable up to 300 ℃.

|

|

Table 1 Physical properties of the catalytic materials used in this work. |

2.2. Epoxidation of propylene

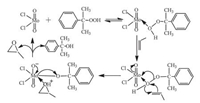

PO was produced during the epoxidation of propylene using CHP as oxidant over the synthesized Mo based catalysts. A schematic representation of the examined reaction and the possible competing side reactions is presented in Scheme 1. A blank experiment was carried out in the absence of catalyst for which an average CHP conversion of 6.6% was obtained due to decomposition of the oxidant. The catalytic results obtained after a reaction time of 8 h in the presence of the catalyst are listed in Table 2.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Schematic representation of the epoxidation of propylene using CHP as oxidant. | |

|

|

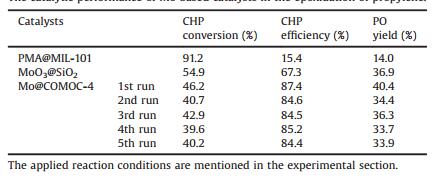

Table 2 The catalytic performance of Mo based catalysts in the epoxidation of propylene. |

As can be seen from Table 2, Mo@COMOC-4 showed approxi mately 46.2% conversion of CHP and a remarkable CHP efficiency of 87.4% after 8 h of reaction at a reaction temperature of 95 ℃. This demonstrates that only a small amount, more specifically 12.6%, is decomposed. The MoO3@SiO2 catalyst, exhibits a CHP conversion of 54.9% and CHP efficiency of 67.3%. The PO yield was 36.9%. However, for the used MoO3@SiO2 catalyst, the Mo loading was 6.65 wt%, which indicates a large number of Mo leached out during catalysis after the first run of the catalytic reaction. Therefore, no further recycling runs were evaluated on this catalyst. In contrast, the PMA@MIL-101 catalyst, which has a higher Mo loading of 13.14 wt%, exhibits a CHP conversion of 91.2%. Nevertheless, the CHP efficiency was considerably lower (15.4%), which means that 84.6% of the CHP was decomposed. This could be due to the Bronsted acidity character of the heteropoly acids which are stronger than conventional solid acids [24]. This might result in a higher CHP conversion and a lower CHP efficiency. The CHP can be easily decomposed into phenol, acetone, acetophenone and other carbonyl compounds according to the competition reactions (2) and (3) shown in Scheme 1.

In order to examine the stability of the Mo@COMOC-4, we have reused the catalyst for at least 5 runs (Table 2). After each run, the catalyst was recovered by filtration, washed with anhydrous alcohol, and dried at room temperature. As can be seen from Table 2, a slight decrease is observed in the CHP conversion during the additional runs. Whereas in the first run a conversion of 46.2% CHP was obtained, a conversion of 40.2% CHP was observed after the fifth run. Moreover, only a minor decrease in the CHP efficiency was noted from 87.4% in the first run towards 84.4% in the fifth run. As mentioned previously, the XRD pattern of the Mo@COMOC-4 after the fifth run shows clearly that the framework integrity is preserved (Fig. 1). Comparison of the FT-IR spectra of the Mo@COMOC-4 before and after catalysis (Fig. 2) also showed no significant differences. More importantly, the Mo species remains constant with a loading of 4.96 wt% after the 5th run, which indicates that there is scarcely any leaching of the Mo species after catalysis. In the end, the PO yield decreased from 40.4% to 33.9%, from which one could conclude that the Mo@COMOC-4 is a stable catalyst exhibiting no significant loss in activity during the epoxidation of propylene.

2.3. Mechanism of epoxidationFrom previous reports employing metal-catalyzed epoxida tion of lower olefins and hydrogen peroxide or organic hydro peroxides as oxidants, mechanisms in which the peroxo species or peroxo compound formed a three-or five-membered ring transition state were suggested [25-28]. Based on these previous studies, a proposed mechanism is illustrated in Scheme 2. In the epoxidation of propylene using CHP as oxidant, the Mo@COMOC-4 acts as a Lewis acid. Firstly, the alkylperoxo complex is generated when using methanol as solvent. Secondly, due to the withdrawing of electrons from the O-O bond of the CHP, this complex renders the peroxidic oxygens more electrophilic and activates the distal oxygen of CHP. This activated distal, electrophilic oxygen will attack the propylene double bond and the oxygen is inserted into the double bond. In the end, the catalyst is regenerated. PO was observed as the main product while α, α-dimethyl benzyl alcohol was the obtained byproduct, which might cause a reversible inhibition reaction due to coordination to the Mo(Ⅵ) center.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Proposed mechanism for the epoxidation of propylene using CHP as oxidant and Mo@COMOC-4 as catalyst. | |

3. Conclusions

Two types of Mo based metal-organic frameworks denoted as Mo@COMOC-4 and PMA@MIL-101(Cr) were synthesized and examined as catalyst in comparison with MoO3@SiO2 in the epoxidation of propylene using cumene hydroperoxide as oxidant. The Mo@COMOC-4 catalyst exhibits a good catalytic performance, with good selectivity and maintained its crystallinity during 5 consecutive runs. Moreover, no significant Mo leaching was observed for Mo@COMOC-4 after 5 runs, which shown remarkable stability compared to MoO3@SiO2, the latter leached out high amount of Mo species after one run. In contrast to the Mo@COMOC-4 with mild acidity, PMA@MIL-101(Cr) with strong Bronsted acidity, resulted a predominant decomposition of CHP with a low PO yield.

4. ExperimentalAll chemicals were commerically available and used without further purification. The synthesis of the MoO2Cl2(THF)2 and subsequent anchoring of this complex onto the COMOC-4 framework was carried out under inert atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques.

4.1. Preparation of the Mo based catalystsMo@COMOC-4 was synthesized according to the procedure published elsewhere [21]. A typical synthetic route is as follows,

Synthesis of Mo@COMOC-4: 0.18 g MoO2Cl2 was added to 7.5 mL dry THF and stirred for 10 min at room temperature. The yellow solution was collected from the non-dissolved residue by employing a combined nylon membrane filter and evaporated to dryness to obtain the MoO2Cl2(THF)2 complex. The obtained complex was re-dissolved in dry THF and a certain amount of COMOC-4 was added. Typically 0.25 g COMOC-4 material was added to a 3 mL MoO2Cl2(THF)2 solution diluted with 37 mL of THF. After stirring the resulting suspension for 1.5 h, the solid product was filtered on a combined nylon-membrane filter and washed several times with acetone to remove unreacted MoO2Cl2(THF)2. The obtained Mo@COMOC-4 was dried under vacuum overnight.

Synthesis of PMA@MIL-101(Cr): PMA@MIL-101(Cr) was synthesized according to a slightly modified procedure published elsewhere [23]. 4.56 g phosphomolybdic acid and 60 mL deionized water were added into a 100 mL Teflon container. After stirring for 10 min, 5.0 g of chromium (Ⅲ) nitrate and 2.08 g of terephthalic acid were added and an additional stirring for 10 min was done before 0.63 g of hydrofluoric acid was added. Hereafter the teflon container was transferred into a autoclave, sealed and heated at 220 ℃ for 8 h. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting greenish solid was filtered. Afterwards the solid was suspended in DMF at 80 ℃ for 3 h. The obtained PMA@MIL-101 was collected by means of centrifuge, washed repeatedly with ethanol to remove the extra PMA which is not well incorporated in MOFs, finally dried overnight at 120 ℃ under vacuum.

Synthesis of MoO3@SiO2: The Mo based SiO2 catalyst was prepared by the incipient wetness impregnation. 0.15 g (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O (99%, TCI) was added to 4.0 mL deionized water, then 0.5 g silica (Aldrich, SBET = 548 m2/g) was added. After impregnation overnight, the samples were dried at 120 ℃ for 12 h and calcined in air at 550 ℃ for 4 h.

4.2. Catalyst characterizationsX-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected on a D/ max-2400 diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 30 mA with 0.02° as step size from 2° to 50°. The Mo content was measured on a PerkinElmer Optima 2000DV ICP-OES. TGA data were obtained by using a Netzsch STA 449 F3 Jupiter-Simultaneous TG-DSC analyzer with a heating rate of 10 ℃ min-1 in air. The BET surface areas were measured on a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 adsorption analyzer at -196 ℃. The samples were activated at 120 ℃ under vacuum overnight prior to the measurements. FT-IR spectra were recorded in the region of 400-4000 cm-1 on a Nicolet-5DX spectrometer (KBr pellet).

4.3. Catalytic testsThe epoxidation reaction of propylene was carried out in a sealed autoclave (200 mL). Typically, 0.1 g catalyst, 7.5 g CHP (70%, in cumene), 9.65 g methanol and 0.35 g butyl amine were added into an autoclave with an initial propylene pressure of 0.5 MPa. The reaction temperature was set at 95 ℃ under a constant magnetic stirring for a reaction time of 8 h.

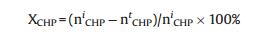

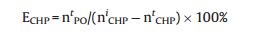

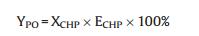

The epoxidation products were analyzed by means of GC equipped with a FID detector and PEG-20 M separation column (30 m × 0.32 mm), and toluene was used as an internal standard. The conversion of CHP was determined by iodometric analysis. As only trace amounts of propylene glycol were detected as byproduct, the selectivity to PO was considered as 100%. The conversion of CHP (XCHP), the CHP efficiency (ECHP) and the yield of PO (YPO) are calculated as follows:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

Wherein nCHPi and nCHPt are the initial and the terminal molar concentration of CHP, respectively; nPOt stands for the molar concentration of PO produced.

AcknowledgementsThis work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21403025), Scientific Research Foundation for Returned Scholars, Ministry of Education of China and the State Key Laboratory of Fine Chemicals (No.KF1405). K.L acknowledged the financial support from the Ghent University BOF-post-doctoral Grant 01P06813T.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2017.01.020.

| [1] | T.A. Nijhuis, M. Makkee, J.A. Moulijn, B.M. Weckhuysen. The production of propene oxide:catalytic processes and recent developments. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 45 (2006) 3447–3459. DOI:10.1021/ie0513090 |

| [2] | J.K.F. Buijink, J.J.M. van Vlaanderen, M. Crocker, F.G.M. Niele. Propylene epoxidation over titanium-on-silica catalyst-the heart of the SMPO process. Catal. Today 93-95 (2004) 199–204. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2004.06.041 |

| [3] | S. Ivanov, R. Boeva, S. Tanielyan. Catalytic epoxidation of propylene with tertbutyl peroxide in presence of molybdenum complexes on polymer carriers. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 5 (1976) 297–301. DOI:10.1007/BF02063039 |

| [4] | V.N. Leonov, A.A. Belyi, G.A. Stozhkova, et al., Catalytic properties of molybdenum-siloxane systems in the reaction of epoxidation of propene by cumene hydroperoxide. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Div. Chem. Sci. 37 (1988) 1765–1768. DOI:10.1007/BF00962483 |

| [5] | Y.X. Miao, G.Z. Lu, X.H. Liu, et al., Effects of preparation procedure in sol-gel method on performance of MoO3/SiO2 catalyst for liquid phase epoxidation of propylene with cumene hydroperoxide. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 306 (2009) 17–22. DOI:10.1016/j.molcata.2009.02.017 |

| [6] | J. Liu, X.L. Ni, Y.K. Hu. Influence of nitridation on the catalytic performance of Ti-MCM-41 for the epoxidation of propene by cumene hydroperoxide. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 114 (2015) 685–695. DOI:10.1007/s11144-014-0803-2 |

| [7] | K.T. Li, P.H. Lin, S.W. Lin. Preparation of Ti/SiO2 catalysts by chemical vapor deposition method for olefin epoxidation with cumene hydroperoxide. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 301 (2006) 59–65. DOI:10.1016/j.apcata.2005.11.012 |

| [8] | K. Shen, X.H. Liu, G.Z. Lu, et al., Lewis acid property and catalytic performance of MoO3/SiO2 for propylene epoxidation by CHP:effects of precipitant pH value and rare earth additive. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 373 (2013) 78–84. DOI:10.1016/j.molcata.2013.02.020 |

| [9] | Y.X. Miao, G.Z. Lu, X.H. Liu, et al., Mo-functionalized MCF meso-material and its catalytic performance for epoxidation of propylene by cumene hydroperoxide. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 122 (2009) 55–60. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2009.02.010 |

| [10] | G. Férey. Hybrid porous solids:past present, future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37 (2008) 191–214. DOI:10.1039/B618320B |

| [11] | M.N. Cele, H.B. Friedrich, M.D. Bala. Liquid phase oxidation of n-octane to C8 oxygenates over modified Fe-MOF-5 catalysts. Catal. Commun. 57 (2014) 99–102. DOI:10.1016/j.catcom.2014.08.002 |

| [12] | S. Sha, H. Yang, J. Li, et al., Co(Ⅱ) coordinated metal-organic framework:an efficient catalyst for heterogeneous aerobic olefins epoxidation. Catal. Commun. 43 (2014) 146–150. DOI:10.1016/j.catcom.2013.09.014 |

| [13] | J.M. Yang, Z.P. Qi, Y.S. Kang, Q. Liu, W.Y. Sun. Shape-controlled synthesis and photocatalytic activity of In2O3 nanostructures derived from coordination polymer precursors. Chin. Chem. Lett. 27 (2016) 492–496. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2015.12.031 |

| [14] | J.W. Ding, R. Wang. A new green system of HPW@MOFs catalyzed desulfurization using O2 as oxidant. Chin. Chem. Lett. 27 (2016) 655–658. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2016.03.005 |

| [15] | H.Q. Xu, J.H. Hu, D.K. Wang, et al., Visible-light photoreduction of CO2 in a metal-organic framework:boosting electron? hole separation via electron trap states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137 (2015) 13440–13443. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b08773 |

| [16] | G. Huang, Y.Z. Chen, H.L. Jiang. Metal-organic frameworks for catalysis. Acta Chim. Sinica 74 (2016) 113–129. DOI:10.6023/A15080547 |

| [17] | J.W. Brown, Q.T. Nguyen, T. Otto, et al., Epoxidation of alkenes with molecular oxygen catalyzed by a manganese porphyrin-based metal-organic framework. Catal. Commun. 59 (2015) 50–54. DOI:10.1016/j.catcom.2014.09.040 |

| [18] | Y.Y. Liu, K. Leus, T. Bogaerts, et al., Bimetallic-organic framework as a zeroleaching catalyst in the aerobic oxidation of cyclohexene. ChemCatChem 5 (2013) 3657–3664. DOI:10.1002/cctc.201300529 |

| [19] | J.J. Wang, M. Yang, W.J. Dong, et al., Co(Ⅱ) complexes loaded into metal-organic frameworks as efficient heterogeneous catalysts for aerobic epoxidation of olefins. Catal. Sci. Technol. 6 (2016) 161–168. DOI:10.1039/C5CY01099C |

| [20] | J.M. Zhang, A.V. Biradar, S. Pramanik, et al., A new layered metal-organic framework as a promising heterogeneous catalyst for olefin epoxidation reactions. Chem. Commun. 48 (2012) 6541–6543. DOI:10.1039/c2cc18127d |

| [21] | K. Leus, Y.Y. Liu, M. Meledina, et al., A MoⅥ grafted metal organic framework:synthesis, characterization and catalytic investigations. J. Catal. 316 (2014) 201–209. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2014.05.019 |

| [22] | K. Leus, G. Vanhaelewyn, T. Bogaerts, et al., Ti-functionalized NH2-MIL-47:an effective and stable epoxidation catalyst. Catal. Today 208 (2013) 97–105. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2012.09.037 |

| [23] | X.F. Hu, Y.K. Lu, F.N. Dai, C.G. Liu, Y.Q. Liu. Host-guest synthesis and encapsulation of phosphotungstic acid in MIL-101 via "bottle around ship":an effective catalyst for oxidative desulfurization. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 170 (2013) 36–44. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.11.021 |

| [24] | I.V. Kozhevnikov. Heteropoly acids and related compounds as catalysts for fine chemical synthesis. Catal. Rev. Sci. Eng. 37 (1995) 311–352. DOI:10.1080/01614949508007097 |

| [25] | K.B. Sharpless, J.M. Townsend, D.R. Williams. Mechanism of epoxidation of olefins by covalent peroxides of molybdenum(Ⅵ). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94 (1972) 295–296. DOI:10.1021/ja00756a062 |

| [26] | R.A. Sheldon, J.A. Van Doorn. Metal-catalyzed epoxidation of olefins with organic hydroperoxides:Ⅰ. A comparison of various metal catalysts. J. Catal. 31 (1973) 427–437. DOI:10.1016/0021-9517(73)90314-X |

| [27] | J. Sobczak, J.J. Ziółkowski. The catalytic epoxidation of olefins with organic hydroperoxides. J. Mol. Catal. 13 (1981) 11–42. DOI:10.1016/0304-5102(81)85028-6 |

| [28] | Y.X. Miao, G.Z. Lu, X.H. Liu, et al., The molybdenum species of MoO3/SiO2 and their catalytic activities for the epoxidation of propylene with cumene hydroperoxide. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 16 (2010) 45–50. DOI:10.1016/j.jiec.2010.01.023 |

2017, Vol. 28

2017, Vol. 28