Neuropathic pain is a chronic disease caused by lesion or dysfunction of the somatosensory system [1, 2]. It can reduce the quality of life of afflicted patients and increase the cost of their medical care, with no specific analgesics available to treat this clinical problem [3, 4].

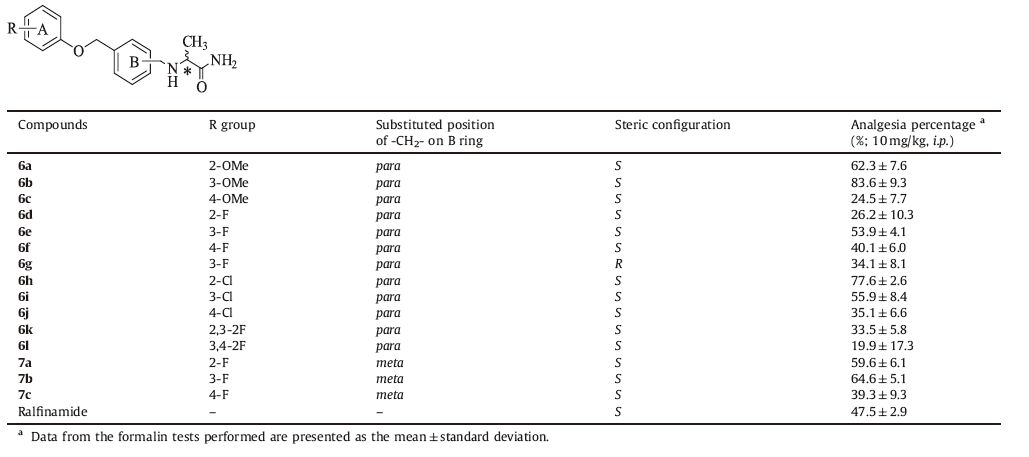

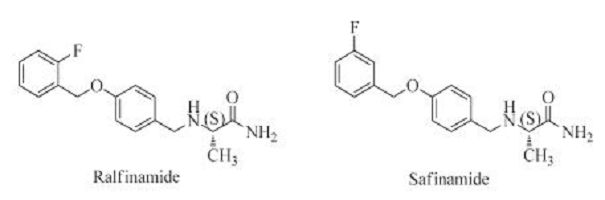

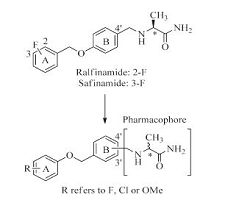

Studies have indicated that the voltage-gated sodium channel subtype 1.7 (Nav1.7) is an ideal therapeutic target for neuropathic pain; and a-aminoamide derivatives, such as ralfinamide (Fig. 1), are thought to be potential antineuropathic drug candidates. Ralfinamide is an orally active Nav1.7-selective blocker with significant analgesic effect in vivo preclinical test and well- tolerated safety profile in clinical studies [5-9]; and it is the only small molecule drug in a late-stage clinical trial for the specific treatment of neuropathic pain [10-14]. Safinamide (Fig. 1) is another a-aminoamide derivative with selective and reversible monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitory activity for treating Parkinson‘s disease (PD) [15-17]. The only structural difference between ralfinamide and safinamide is the position of the fluoro substituent (Fig. 1). Based on the distinct pharmacological activity of these two compounds, detailed structure-activity relationship studies are needed to further characterize α-aminoamides.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 1. Chemical structures of ralfinamide (A) and safinamide (B) | |

In this article, we report a set of novel compounds that combine a substituted benzene group with the pharmacophore of a- aminoamide (Fig. 2). Drug-design strategies based on the theory of bioisosterism were applied: (i) we replaced the A ring of ralfinamide with fluorine/chlorine/methoxyl substituted benzene moiety and varied the substitution position of the benzene ring and the pharmacophore; (ii) the relative position of oxygen atom and methylene group between A ring and B ring ofralfinamide was also changed. The bioactivities of the resulting compounds were subsequently evaluated and compared.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 2. The design of novel a-aminoamide derivatives. R group in A ring refers to F, Cl or OMe. Substitutions involving the a-aminoamide pharmacophore were made in the B ring at either the 3' or 4' position; and the steric configuration of pharmacophore can be S or R | |

2. Experimental 2.1. Chemistry

Reagents and solvents were purchased from Beijing Chemical Works (Beijing, China), Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium) & Alfa- Aesar (Massachusetts, USA), and were used without further purification. 1H-NMR (400 MHz) spectra were measured on a JNM-ECA-400 spectrometer (JEOL Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-d6 as a deuterium solvent. Mass spectra (MS) were measured on an API-150 mass spectrometer (ABI Inc, Texas, USA) with the electrospray ionization source (Agilent Technologies Inc., California, USA). Reaction progress was determined by thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis on silica gel HSGF254 plates. Silica gel (Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Shandong, China) was used for column chromatography. Product purification was determined by using a CombiFlash Companion Rf Preparative Chromatograph (Teledyne Isco Inc., Nebraska, USA).

Synthesis of 4-(hydroxymethyl)benzaldehyde (2a) and 3- (hydroxymethyl)benzaldehyde (2b): A solution of terephthalalde- hyde (1a, 20.0 g) or isophthalaldehyde (1b, 20.0 g) in ethanol (100 mL) and tetrahydrofuran (150 mL) was added NaBH4 1.7 g for 6 h with stirring. After the reaction was complete, the solution was quenched with 2 mol/L hydrochloric acid to the pH 5-6. Water and ethyl acetate were added to the residue. The aqueous phase was extracted with ethyl acetate three times, and the organic phase was washed with saturated NaCl solution, dried over Na2SO4 in 8 h. Products were purified by silica gel column chromatography using petroleum ether: ethyl acetate (5:1) as the eluent to afford 17.6 g of intermediate 2a or 16.4 g of intermediate 2b as white solid. Yield: 86.1% (2a) and 80.2% (2b).

Synthesis of 4-(bromomethyl)benzaldehyde (3a) and 3-(bro- momethyl)benzaldehyde (3b): A solution of 2a or 2b (10.0 g) in dichloromethane (120 mL) was added NBS (19.6 g). Then triphe- nylphosphine 38.5 g was slowly added to the solution in 30 min. After 3 h, the reaction was complete, then the solution was mixed with cold water (120 mL). The aqueous phase was extracted two times with dichloromethane, the organic phase was washed with saturated NaCl solution, dried over Na2SO4 in 8 h. Products were purified by silica gel column chromatography using petroleum ether: ethyl acetate (25:1) as the eluent to afford 8.5 g of intermediate 3a as white solid or 6.8 g of intermediate 3b as lightyellow solid. Yield: 58.0% (3a) and 46.8% (3b).

General procedure for preparation of intermediate 4a-l: A solution of 3a (1.0 equiv.) in acetone was added R-substituted phenol (1.1 equiv.), potassium carbonate (3.0 equiv.) and potassium iodide (0.6 equiv.). The mixture was heated to 58 ℃ for 24 h. After the reaction was complete, ethyl acetate was added to the residue, then the organic phase was washed with 0.5 mol/L NaOH solution and saturated NaCl solution, dried over Na2SO4 in 8 h. Products were purified by silica gel column chromatography using petroleum ether:ethyl acetate (7:1) as the eluent to afford 4a-l as lightyellow solid. Yield: 52.8%-60.4%.

General procedure for preparation of intermediate 5a-c: A solution of 3b (1.0 equiv.) in DMF (40 mL) was added 2-fluoro/3- fluoro/4-fluoro substituted phenol (1.1 equiv.), cesium carbonate (1.5 equiv.) and potassium iodide (0.6 equiv.). The mixture was heated to 40 ℃ for 12 h. After the reaction was complete ethyl acetate was added to the residue, then the organic phase was washed with 0.5 mol/L NaOH solution and saturated NaCl solution, dried over Na2SO4 in 8 h. After filtration and evaporation under reduced pressure, products were purified by silica gel column chromatography using petroleum ether:ethyl acetate (7:1) as the eluent to afford 5a-c as light yellow solid. Yield: 48.5%-60.9%.

General procedure for preparation of target compounds 6a-l: A solution of L-alaninamide or D-alaninamide hydrochloride (1.1 equiv.), sodium cyanoborohydride (0.8 equiv.), 1 g of 3Å molecular sieve and 1 mL of triethylamine in methanol (40 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 15 min, then 4a-l (1.0 equiv.) was rapidly added. The mixture was heated to 40 ℃ for 8 h. After the reaction was complete, the solution was filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Then water and ethyl acetate were added, and the organic phase was washed with saturated NaCl solution, dried over Na2SO4 in 8 h. Products were purified by silica gel column chromatography (gradient elution: methanol/ dichloromethane, 0-5%, 30 min) to afford 6a-l as white solid. Yield: 28.7%-35.0%.

General procedure for preparation of target compounds 7a-c: Compounds 7a-c were synthesized by a similar procedure as 6a-l, except compounds 4a-l were replaced by 5a-c at this reaction procedure. The resulting compounds 7a-c were obtained as white solids in yields of 33.5%-40.1%. Spectral data for target compounds 6a-l and 7a-c (spectra are in Figs. S1-S15 in Supporting information):

6a: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.34-7.35 (m, 4H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.83-6.94 (m, 4H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 3.34-3.68 (m, 5H), 2.97-3.01 (m, 1H), 1.12 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 315.2, (M + Na+) 337.2.

6b: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.35-7.37 (m, 4H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.83-6.94 (m, 4H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 3.34-3.68 (m, 5H), 2.97-3.01 (m, 1H), 1.11 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 315.2, (M + Na+) 337.2.

6c: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.35-7.36 (m, 4H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.83-6.94 (m, 4H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 3.34-3.68 (m, 5H), 2.97-3.01 (m, 1H), 1.12 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 315.1, (M + Na+) 337.2.

6d: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.34-7.38 (m, 6H), 7.10 (s, 2H), 6.77-6.91 (m, 3H), 5.09 (s, 2H), 3.52-3.70 (m, 2H), 2.99-3.01 (m, 1H), 1.13 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 303.1, (M + Na+) 325.1.

6e: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.31-7.35 (m, 6H), 7.02 (s, 2H), 6.81-6.93 (m, 3H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 3.45-3.60 (m, 2H), 2.89-2.96 (m, 1H), 1.21 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 303.1, (M + Na+) 325.1.

6f: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.30-7.65 (m, 6H), 7.18 (s, 2H), 6.84-7.00 (m, 3H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 3.45-3.60 (m, 2H), 2.89-2.96 (m, 1H), 1.21 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 303.1, (M + Na+) 325.1.

6g: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.31-7.69 (m, 6H), 7.11 (s, 2H), 6.77-6.95 (m, 3H), 4.98 (s, 2H), 3.41-3.62 (m, 2H), 2.90-3.01 (m, 1H), 1.25 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 303.2, (M + Na+) 325.1.

6h: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): d 7.34-7.38 (m, 6H), 7.10 (s, 2H), 6.77-6.91 (m, 3H), 5.09 (s, 2H), 3.52-3.70 (m, 2H), 2.99-3.01 (m, 1H), 1.13 (d, 3H, J = 6.7Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 319.1, (M + Na+) 341.1.

6i:1HNMR(400MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.31-7.35(m, 6H), 7.02(s, 2H), 6.81-6.93 (m, 3H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 3.45-3.60 (m, 2H), 2.89-2.96 (m, 1H), 1.21 (d, 3H, J = 6.7Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 319.1, (M + Na+) 341.1.

6j:1HNMRH(400MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.30-7.65(m, 6H), 7.18(s, 2H), 6.84-7.00 (m, 3H), 5.12 (s, 2H), 3.45-3.60 (m, 2H), 2.89-2.96 (m, 1H), 1.21 (d, 3H, J = 6.7Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 319.1, (M + Na+) 341.1.

6k:1HNMR(400MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.26-7.56(m, 5H), 7.10(s, 2H), 6.52-6.81 (m, 3H), 4.99 (s, 2H), 3.40-3.65 (m, 2H), 2.95-3.07 (m, 1H), 1.20 (d, 3H, J =6.7Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 321.1, (M + Na+) 343.1.

6l: 1H NMR(400MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.14 (s, 2H), 7.91(s, 1H), 6.80-7.63 (m, 7H), 5.08 (s, 2H), 4.02-4.11 (m, 2H), 3.72-3.74 (m, 1H), 1.39 (d, 3H, J = 6.7 Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 321.1, (M + Na+)343.1.

7a: 1HNMR(400MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.34-7.38(m, 6H), 7.10(s, 2H), 6.77-6.91 (m, 3H), 5.09 (s, 2H), 3.52-3.70 (m, 2H), 2.99-3.01 (m, 1H), 1.13 (d, 3H, J = 6.7Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 303.1, (M + Na+) 325.1.

7b: 1HNMR(400MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.36-7.39(m, 6H), 7.12(s, 2H), 6.77-6.91 (m, 3H), 5.09 (s, 2H), 3.52-3.70 (m, 2H), 2.99-3.01 (m, 1H), 1.13 (d, 3H, J = 6.7Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 303.1, (M + Na+) 325.1.

7c: 1HNMR(400MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.35-7.38 (m, 6H), 7.10(s, 2H), 6.77-6.91 (m, 3H), 5.09 (s, 2H), 3.53-3.74 (m, 2H), 3.09-3.21 (m, 1H), 1.13 (d, 3H, J = 6.7Hz). MS (ESI) m/z: (M + H+) 303.1, (M + Na+) 325.1.

2.2. Mice formalin testThe formalin test in rodents is a widely accepted assay for screening neuralgia drugs and it involves an injection of formalin to provide a biphasic pain response [18]. Phase 1 (0-5 min afteran injection of a 2.7% formalin solution) refers to the acute pain phase, and phase 2 (15-30 min after the formalin injection) refers to the chronic pain phase. As a result of inflammatory reaction caused by peripheral nerve injury, phase 2 simulates the symptoms ofclinical chronic neuropathic pain [6]. Thus, a significant reduction of pain behavior during phase 2 may indicate a marked anti-allodynic effect on neuropathic pain.

Target compound hydrochlorates were prepared and ralfi- namide methanesulfonate was used as a positive control. All the test drugs were dissolved in distilled water before testing. According to a modified protocol from Veneroni et al. [6], ICR mice (weight: 22-25 g) from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) were administered ralfi- namide or one of the test compounds by intraperitoneal route at a dose of 10 mg/kg inavolume of 10 mL/kg body weight (6 mice per group). After 30 min, mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) with 20 mL of 2.7% formalin solution into the plantar surface of left hind paw and placed instantly into PVC observation chambers (23 × 12 × 13 cm3). Pain behavior in phase 2 was quantified by counting the cumulative licking time (s) of the injected paw.

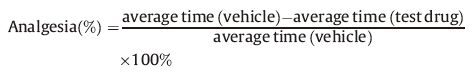

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of six animals per dose group, and evaluated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. The raw data of cumulative licking time were converted to percent (%) analgesia, according to the following formula:

|

At room temperature, whole-cell voltage clamp recordings were performed on recombinant HEK293 cell line expressing the human Nav1.7 using an EPC 10 amplifier (HEKA Electro-nics, Germany). To measure the inactivated Nav1.7 channels, the currents were recorded under a holding potential at -120mV and then depolarized to 0 mV for 1 s to inactivate the sodium currents (TP1). Then the membrane potential was repolarize to - 120 mV for 20 ms, and following a depolarized pulse to 0 mV (TP2). The peak current of TP1 and TP2 were recorded and analyzed independently. This voltage-clamp pulse protocol was performed during the experiment. An interpulse interval of 10 s allows recovery from inactivation. Fast perfusion system should be used to apply drugs directly to the cell in seconds. Each concentration was perfused over 2 min, or until the current reached a steady- state level. After the final concentration of reference agent tested, the reference compound should be washed out with extracellular solution for 5 min. Within each cellular recording, the current responses to test compound addition were normalized to the vehicle control (= Icompound/Ivehicle control) and the ratios of inhibition were calculated (= 1 - [current response/maximal control tail current]×100%). Means and standard errors were calculated for each test group.

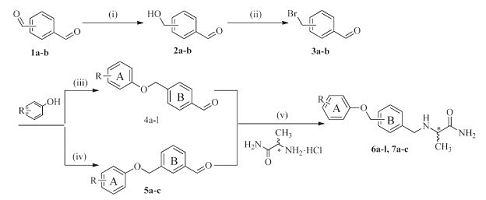

3. Results and discussion 3.1. Synthesis of intermediates and test compoundsThe strategies for synthesizing target compounds 6a-l and 7a-c are shown in Scheme 1. First, the aldehyde group of tere- phthalaldehyde (1a) or isophthalaldehyde (1b) was reduced selectively by sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a reducing agent. In the reaction, the molar amount of NaBH4 was used just one quarter of that of 1a or 1b; and the reaction temperature was also cooled down with ice-bath, in order to lower the reaction activity of reducing agent. These synthetic strategies can help us to reduce only one aldehyde group of 1a or 1b to become an alcohol group, at the same time, keep the other aldehyde group unchanged. Then 2a or 2b was bromated with N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) using triphenylphosphine (PPh3) as a catalyst to obtain the intermediate 3a or 3b. Next, 3a or 3b was etherified with substituted phenols by Williamson ether synthesis. Finally, 4a-l or 5a-c were converted into a series of a-aminoamide derivatives by reductive amination. The optical purities of the target compounds have been determined by HPLC with a chiral column (Venusil CO; 5 mm, 1000 A; 4.6×250 mm; Bonna-Agela Technologies). As can be seen in Figs S16-S23 in Supporting information, they are pure optical compounds.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme. 1. Synthesis of compounds 6a-l and 7a-c: (i) NaBH4, C2H5OH, THF, ice-bath, 6 h; (ii) NBS, PPh3, DCM, 4.5 h; (iii) K2CO3, KI, acetone, 58 ℃, 24 h; (iv) Cs2CO3, DMF, 40 ℃, overnight; (v) L- or D-Alaninamide hydrochloride, NaBH3CN, MeOH, 8 h | |

3.2. Analgesic activity of target compounds in formalin test

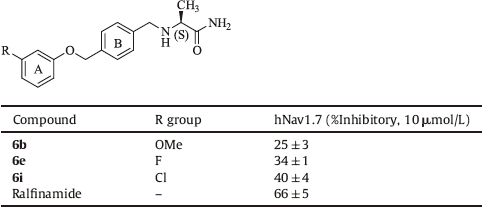

As shown in Table 1, some of the test compounds exhibited significant analgesic efficacy in phase 2 of the formalin test (P value <0.05; compared with vehicle group). In particular, compound 6b exhibited 83.6% of analgesia percentage by i.p. administration at the dose of 10 mg/kg. The SAR studies have suggested that compounds 6b, 6e, and 7b with substitution made in the A ring at 3 position exhibited relatively higher analgesic activity than compounds with fluorine atom or methoxyl substitution made in the A ring at 2 or 4 position. By contrast, compound 6h with chlorine atom substitution made in the A ring at 2 position exhibited relatively higher analgesic activity than 6i and 6j with chlorine atom substitution made in the A ring at 3 or 4 position. In addition, compounds 6k and 6l with two fluorine atom substitution made in the A ring exhibited lower analgesic activity than 6e, indicating that multiple fluorine atom substitution in the A ring may not be beneficial to improvement of analgesic activity of target compounds. The (R)-enantiomer 6g appeared to be disadvantageous to the analgesic activity, compared to the (S)-enantiomer 6e.

|

|

Table 1 In vivo activity of target compounds assessed by the formalin test |

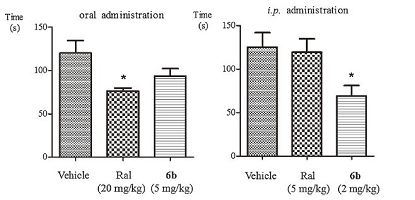

Further investigation has suggested that compound 6b Exhibits 44.4% analgesia upon i.p. administration at 2 mg/kg, which are more potent than that observed for ralfinamide (4.9% analgesia upon i.p. administration at 5 mg/kg). While compound 6b and ralfinamide Exhibits 24.8% and 36.5% analgesia upon oral administration at 5 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg, respectively. Data for cumulative licking time are presented in Fig. 3.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 3. Duration of licking time upon oral and intraperitoneal administration of ralfinamide and compound 6b during the formalin test. Significant differences between vehicle and drug-treated groups were evaluated by the Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05 | |

3.3. In vitro inhibitory activities of the test compounds on the inactivated human-Navl.7 (hNavl.7)

Target compounds 6b, 6e and 6i, which exhibited good analgesic activity on formalin test, were evaluated for in vitro activities with whole cell patch-clamping assays of recombinant HEK293 cells expressing Nav1.7. The inhibitory activities of the compounds are listed in Table 2. The compounds were screened at a single dose of 10 mmol/L according to the IC50 of ralfinamide (7.10 ± 1.41 μmol/L). As shown in Table 2, test compounds can moderately inhibit hNav1.7.

|

|

Table 2 Inhibitory activities of selected compounds on the tetrodotoxin-sensitive inactivated hNav1.7 |

Neuropathic pain is one of the most complex pain syndromes to manage with no specific drug available clinically. The a- aminoamide derivatives such as ralfinamide have been proved to be promising candidates for treating neuropathic pain. Thus, we designed and synthesized a set of novel a-aminoamide derivatives containing substituted benzene groups different from that of ralfinamide and evaluated their biological activities. We first screened the in vivo activities of the novel compounds in mice formalin model, because our studies have suggested the compounds with the oxygen atom at this position exhibited lower in vitro Nav1.7 inhibitory activity than that of ralfinamide. In agreement with our design, several novel compounds containing the -OMe or -Cl substituted benzene group exhibited higher potency compared with that of ralfinamide. Thus we further tested the in vitro inhibitory activities of these compounds on Nav1.7. Confirmed with prediction, they displayed lower Nav1.7 selectivity than that of ralfinamide, indicating different target and mechanism of action for these new compounds.

4. ConclusionIn conclusion, a series of novel a-aminoamide derivatives containing novel substituted benzene groups were designed and synthesized. In vivo assessments of the target compounds using a formalin assay showed that some of them exhibit more potent analgesic activity than that of ralfinamide. Further studies on the analgesic mechanism of actions of these compounds are ongoing.

AcknowledgmentsThis research was supported, in part, by a grant from the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Project (No. Z131100002713004) and a National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2012ZX09301003).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/jxclet2016.06.034.

| [1] | R. Baron, A. Binder, G. Wasner. Neuropathic pain:diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 9 (2010) 807–819. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70143-5 |

| [2] | M. Costigan, J. Scholz, C.J. Woolf. Neuropathic pain:a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32 (2009) 1–32. DOI:10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531 |

| [3] | I. Yalcin, F. Barthas, M. Barrot. Emotional consequences of neuropathic pain:insight from preclinical studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 47 (2014) 154–164. DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.08.002 |

| [4] | M. Gangadhar, R.K. Mishra, D. Sriram, P. Yogeeswari. Future directions in the treatment of neuropathic pain:a review on various therapeutic targets. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 13 (2014) 63–81. DOI:10.2174/18715273113126660192 |

| [5] | B.T. Priest, G.J. Kaczorowski. Blocking sodium channels to treat neuropathic pain. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 11 (2007) 291–306. DOI:10.1517/14728222.11.3.291 |

| [6] | O. Veneroni, R. Maj, M. Calabresi, et al. Anti-allodynic effect of NW-1029, a novel Na+ channel blocker, in experimental animal models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Pain 102 (2003) 17–25. DOI:10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00183-5 |

| [7] | H. Yamane, W.C. de Groat, A. Sculptoreanu. Effects of ralfinamide, a Na+ channel blocker, on firing properties of nociceptive dorsal root ganglion neurons of adult rats. Exp. Neurol. 208 (2007) 63–72. DOI:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.010 |

| [8] | F. Cattabeni. Ralfinamide. Newron pharmaceuticals. IDrugs 7 (2004) 935–939. |

| [9] | O. Veneroni, R. Maj, M. Calabresi, et al., Antihyperalgesic effect of NW-1029, a novel Na+ channel blocker in animal models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain, in:in:International Association for the Study of Pain, 10th World Congress on Pain, San Diego, CA, USA, 2002. |

| [10] | M. Bauer, H. Bliesath, C. Leuratti, et al. Disposition and metabolism of ralfinamide, a novel Na-channel blocker, in healthy male volunteers. Pharmacology 86 (2010) 297–305. DOI:10.1159/000321322 |

| [11] | Y.Y. Wang, S.M. Wilson, J.M. Brittain, et al. Merging structural motifs of functionalized amino acids and α-aminoamides results in novel anticonvulsant compounds with significant effects on slow and fast inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels and in the treatment of neuropathic pain. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2 (2011) 317–332. DOI:10.1021/cn200024z |

| [12] | C. Salomé, E. Salomé-Grosjean, J.P. Stables, H. Kohn. Merging the structural motifs of functionalized amino acids and α-aminoamides:compounds with significant anticonvulsant activities. J. Med. Chem. 53 (2010) 3756–3771. DOI:10.1021/jm100185c |

| [13] | I. Macsari, Y. Besidski, G. Csjernyik, et al. 3-oxoisoindoline-1-carboxamides:potent, state-dependent blockers of voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.7 with efficacy in rat pain models. J. Med. Chem. 55 (2012) 6866–6880. DOI:10.1021/jm300623u |

| [14] | H. Bregman, L. Berry, J.L. Buchanan, et al. Identification of a potent, statedependent inhibitor of Nav1.7 with oral efficacy in the formalin model of persistent pain. J. Med. Chem. 54 (2011) 4427–4445. DOI:10.1021/jm200018k |

| [15] | E.D. Deeks. Safinamide:first global approval. Drugs 75 (2015) 705–711. DOI:10.1007/s40265-015-0389-7 |

| [16] | C. Cattaneo, R. La Ferla, E. Bonizzoni, M. Sardina. Long-term effects of safinamide on dyskinesia in mid- to late-stage parkinson's disease:a post-hoc analysis. J. Parkinsons Dis. 5 (2015) 475–481. DOI:10.3233/JPD-150569 |

| [17] | M. Fabbri, M.M. Rosa, D. Abreu, J.J. Ferreira. Clinical pharmacology review of safinamide for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 5 (2015) 481–496. DOI:10.2217/nmt.15.46 |

| [18] | M. Shibata, T. Ohkubo, H. Takahashi, R. Inoki. Modified formalin test:characteristic biphasic pain response. Pain 38 (1989) 347–352. DOI:10.1016/0304-3959(89)90222-4 |

2016, Vol. 27

2016, Vol. 27