b Key Laboratory for the Chemistry and Molecular Engineering of Medicinal Resources, the Ministry of Education of China, School of Chemistry and Pharmacy, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin 541004, China ;

c Hainan Bikai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Haikou 570216, China

The rhizomes of Curcuma wenyujin (C. wenyujin) Y. H. Chen et C. Ling(Zingiberaceae) are used asaTraditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) for the treatment of jaundice, thoracic-abdominal pain, arthralgia, hematuria, dysmenorrhea, epilepsy, and psychataxia [1, 2]. The recent pharmacological studies of this plant have shown a variety of bioactivities, including antiviral [3], anticancer [4], antioxidation [5, 6], and anti-inflammatory [7, 8]. The essential oil of C. wenyujin has listed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2010) as an antiviral remedy to cure pediatric diseases, such as acute upper respiratory infections, viral myocarditis, or acute pneumonias [9-11].

The essential oil of C. wenyujin has anti-inflammatory, broken blood stasis and relieved pain effects. Hainan Bikai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. produces the drug "bao fu kang shuan" with essential oil as the main ingredient. This drug is used primarily as a treatment of [1] [2] ould sex vaginitis, senile vaginitis, and cervical erosion. Near 1, 000 tons of C. wenyujin dreg were produced for one year. At present, the mainly treatment for the C. wenyujin dreg is simple disposal. This not only cause pollution to the environment, but also cause great waste of resources. In order to further develop and comprehensively utilize the C. wenyujin dreg, the chemical constituents, and pharmacological activities of the C. wenyujin dreg were investigated.

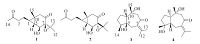

In order to make the best of the wenyujin dreg, a systematic phytochemical study of the compounds in the C. wenyujin dreg was adopted. Four new sesquiterpenoids including 4, 8-dioxo-6β- hydroxyl-7b, 11-epoxycarabrane (1), 4, 8-dioxo-6β-hydroxyl-7a, 11-epoxycarabrane (2) and wenyujinins Q and R (3 and 4), along with nine known sesquiterpenoids (5-13), including isozedoarondiol (5) [12], zedoarondiol (6) [13], neoprocurcumenol (7) [14], phaeocaulisin E (8) [15], (1S, 4S, 5S, 10S)-1, 10:4, 5-diepox- ygermacrone (9) [16], octahydro-5, 8-dihydroxy-5, 8α-dimethyl-3- (1-methylethylidene) (10) [17], elemα-1, 3, 7 (11), 8-tetraen-8, 12- lactam (11) [18], wenyujinin E (12) [8], curcumadione (13) [19] were isolated, and their antibacterial and antifungal activities were determined. Herein, we report the isolation, structure elucidation, and biological activities of these compounds.

2. Experimental 2.1. General experimental procedures1D (1H, 13C, DEPT) and 2D (1H-1H COSY, NOESY, HMQC, HMBC) NMR spectra were recorded on a bruker Av400 NMR spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million (ppm), using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard; coupling constants (J) are in hertz (Hz). Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI- MS) spectra were recorded on an Agilent 1200 series HPLC interfaced to a Bruker Esquire 6000 Ion Trap mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source and high resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS) spectra were obtained on a Micromass Q-TOF spectrometer. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separation was performed in Agilent-HPLC (Eclipse XDB-C18, 10 × 250 mm, 5 mm). UV spectra were recorded on a Unico UV/vis 2802 PCS spectrophotometer (Unico Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, PR China). IR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet Nexus 470 spectrometer using KBr pellets. Silica gel (100 - 200 and 200 - 300 mesh) was obtained from the Qingdao Marine Chemical Factory, Sephadex LH-20 was manufactured by Pharmacia Co., Ltd., and octadec ylsilyl silica gel (45 - 60 μm) were used for column chromatography. TLC silica gel GF254 plates obtained from the Qingdao Marine Chemical Factory were used for thin layer chromatography (TLC).

2.2. Plant materialThe C. wenyujin dreg was collected from Hainan Bikai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. in June, 2013. The C. wenyujin dreg was deposited in the Key Laboratory of Topical Medicine Plant Chemistry of Ministry of Education of China, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Hainan Normal University of China, Haikou, China.

2.3. Extraction and isolationThe C. wenyujin dreg (30 kg) was extracted with 65% EtOH in the room temperature (3 × 5 d). Evaporation of the solvent under reduced pressure gave the ethanolic extract (3.5 kg). The ethanolic extract was then partitioned into a petroleum ether-H2O (1:1, v/v) mixture and removal of the solvent in vacuo yielded a petroleum ether-soluble fraction, and an aqueous phase. Then petroleum ether- soluble fraction was concentrated to give the petroleum ether extract (40 g) and then the aqueous phase mixture with ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v), and removal of the solvent in vacuo yielded an ethyl acetate-soluble fraction and an aqueous phase. Then ethyl acetate-soluble fraction was concentrated to give the ethyl acetate extract (500 g).

The petroleum ether extract (40 g), which was subjected to silica gel column chromatography (CC) (petroleum ether-EtOAc v/ v, gradient 100:0-0:100) to afford 10 fractions (FrA.1 - FrA.10). FrA.3 was subjected to reversed-phase silica gel CC and Sephadex LH-20 CC to afford 9 (6.5 mg) and 13 (6.0 mg). FrA.4 (9.01 g) was isolated by CC on silica gel eluted with petroleum ether-EtOAc (25:1) and then subjected to Sephadex LH-20 CC eluting with mixtures of CHCl3-MeOH/petroleum ether (v/v, 1:1:2) to obtain8 fractions (FrA.4-1-FrA.4-8). FrA.4-8 was subjected to silica gel CC and repeated Sephadex LH-20 CC (CHCl3/MeOH, v/v, 1:1) and further purified by using HPLC on an ODS semi-preparative column (Eclipse XDB-C18, 10 × 250 mm, 5 μm, 2 mL/min) eluted with 45% MeCN/H2O to obtain 1 (5.0 mg) and 2 (7.0 mg). FrA.6 was subjected to repeated Sephadex LH-20 CC (MeOH) and further purified on HPLC (30% CH3CN/H2O) to afford 7 (3.8 mg) and 12 (20.3 mg).

The ethyl acetate extract (500 g), which was subjected to silica gel CC (petroleum ether-EtOAc v/v, gradient 100:0-0:100) to afford 10 fractions (FrB.1 - FrB.10). FrB.3 was isolated by CC on silica gel eluted with CHCl3-CH3COCH3(20:1) and then subjected to Sephadex LH-20 CC eluting with mixtures of CHCl3-MeOH (v/v, 1:1) to obtain six fractions (FrB.3-1-FrB.4-6). FrB.3-2 dissolved in methanol and filtered to give the insoluble material that recrystallized with CHCl3 to obtain 11 (25.5 mg). FrB.3-4 and FrB.3-6 further purified by using HPLC on an ODS semi-preparative column (Eclipse XDB-C18, 10 × 250 mm, 5 μm, 2 mL/min) eluted with 30% MeCN/H2O to obtain 3 (7 mg), 5 (5.5 mg), and 8 (11.3 mg), respectively. FrB.6 was isolated by CC on silica gel eluted with CHCl3-CH3COCH3(20:1) and then subjected to Sephadex LH- 20 CC eluting with mixtures of CHCl3-MeOH (v/v, 1:1) to obtain six fractions (FrB.6-1-FrB.6-6). FrB.6-2 was further purified by HPLC (25% CH3CN/H2O) to obtain 6 (7 mg), FrB.6-3 was isolated by preparation of TLC and further purified by HPLC (25% CH3CN/H2O) to obtain 4 (5.0 mg) and 10 (12.0 mg). The structures of the isolated compounds are depicted in Fig. 1.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 1. Structures of compounds 1-4. | |

4, 8- Dioxo-6β-hydroxyl-7β, 11-epoxycarabrane (1): Yellow oil; [α]D25= +109.8 (c = 0.28, MeOH); UV λmax (MeOH, nm): 200; IR (KBr, cm-1) υmax: 2921, 1716, 1685, 1456, 1372, 1160, 1085;1H and 13C-NMR data see in Tables 1 and 2; ESI-MS m/z 267.1 [M + H]+; HR-ESI-MS m/z 289.1537 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C15H22O4Na, 289.1560).

|

|

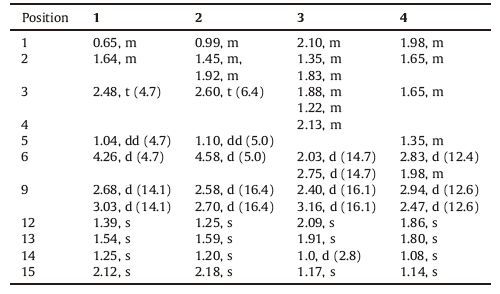

Table 1 1H NMR (400 MHz, δ in ppm, J in Hz) date of compounds 1-4 in CDCl3. |

|

|

Table 2 13C NMR (100 MHz, δ in ppm) data of compounds 1-4 in CDCl3. |

4, 8- Dioxo-6β-hydroxyl-7α, 11-epoxycarabrane (2): Yellow oil; [α]D25 =+ 46.5 (c = 0.34, MeOH); UV λmax (MeOH, nm): 200; IR(KBr, cm-1) Umax: 2922, 1714, 1686, 1455, 1370, 1163, 1090; 1H and 13C- NMR data see Tables 1 and 2; ESI-MS m/z 267.1 [M + H]+; HR-ESI- MS m/z 289.1468 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C15H22O4Na, 289.1560).

Wenyujinin Q (3): White amorphous powder; [α]D25 = - 125 (c = 0.16, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax: 250 nm; IR (KBr, cm-1) υmax 3747, 3648, 1700, 1650, 1540, 1510 cm-1; 1H and 13C-NMR data see Tables 1 and 2; ESI-MS m/z 275.4 [M + Na]+; HR-ESI-MS m/z 275.1620 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C15H24O3Na, 275.1618).

Wenyujinin R (4): Colorless needles; [α]D25= -120 (c = 0.16, MeOH); UV (MeOH)λmax: 250 nm; IR (KBr) υmax 3747, 3648, 1700, 1650, 1540, 1510 cm-1; 1H and 13C-NMR data see in the Tables 1 and 2; ESI-MS m/z 275.2 [M + Na]+; HR-ESI-MS m/z 275.1618 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C15H24O3Na, 275.1618).

2.4. Biological assays 2.4.1. Antibacterial activitiesThe antibacterial activity against seven bacterial strains, Escherichia coli (E. coli) (ATCC 25922), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (ATCC 27154), Staphylococcus albus (S. albus) (ATCC 8799), Bacillus cereus (B. cereus) (ACCC 11077), Micrococcus luteus (M. luteus)(ACCC 11001), Micrococcus tetragenus (M. tetragenus) (ATCC 13623), and Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis)(ACCC 11060) were determined by a serial dilution technique using 96-well microtiter plates [22]. The compounds were dissolved in DMSO to give a stock solution. Bacterial species were cultured overnight at 37 ℃ in LB broth and diluted to 106 cfu/mLwhen used. LB broth was used as a blank control, and DMSO was used as a negative control, while ciprofloxacin was used as a positive control. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest test concentration that completely inhibited the growth of the test organisms.

2.4.2. Antifungal activitiesAntifungal bioassays were conducted following the National Center for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) recommendations. Nine phytopathogenic fungal strains: Alternaria brassicicola (A. brassicicola), Phytophthora parasitica var. nicotianae (P. parasitica var. nicotianae), Colletotrichum capsici (C. capsici), Bipolaris oryzae (B. oryzae), Diaporthe medusaea nitschke (D. medusaea Nitschke), Ceratocystis paradoxa moreau(C. paradoxa moreau), Exserohilum turcicum (E. turcicum), Pestalotia theae (P. theae), and Alternaria citri (A. citri) were grown on potato dextrose agar. Targeted microbes (three to four colonies) were prepared from broth culture (28 ℃ for 48 h), and the final spore suspensions of fungi were 104 mycelial fragments/mL. Test samples(100 μg/mLas stock solution in DMSO and serial dilutions) were transferred to a 96-well clear plate in triplicate, and the suspension of the test organisms was added to each well achieving a final volume of 200 μL. Prochloraz was used as a positive control. The plates were stored in controlled- environment cabinets from 4 to 14 days, depending on the assay, and mycelial growth was then assessed. After incubation, the absorbance at 492 nm was measured with a microplate reader. The MIC was defined as the lowest test concentration that completely inhibited the growth of the test organisms.

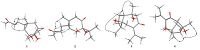

3. Results and discussion4, 8- Dioxo-6β-hydroxyl-7β, 11 -epoxy carabrane (1) was obtained as a colorless oil with positive optical rotation [α]D25 =+109.8 (c = 0.28, MeOH). Its molecular formula was determined as C15H22O4 (five degrees of unsaturation) from its HR-ESI-MS spectrum (m/z 289.1537 [M + Na]+) and combined with 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data (Tables 1 and 2). The absorption band in IR spectrum of 1 indicated the presence of a carbonyl group (1651 cm-1). The 1H-NMR data for 1 exhibited typical signals for a sesquiterpene with a carabrane-type skeleton, including four methyl groups [δH 1.25(s, 3H), 1.39(s, 3H), 1.54(s, 3H), 2.12 (s, 3H)], and two protons of a cyclopropane [δH 0.65 (m, 1H), 1.04 (t, 1H, J = 4.7 Hz)]. The 13C-NMR spectrum of 1, in combination with the DEPT and HMQC spectra, showed 15 carbon signals that were classified into four methyls (d〔 19.1, 19.2, 22.7, 31.1), three methylenes (δC 22.9, 43.6, 47.9), three methines (δC 25.5, 26.2, 81.8), and five quaternary carbons (δC 21.1, 65.6, 66.5, 206.7, 208.1). These spectra data (Table 1) were very similar to those of4, 8-dioxo- 6β-methoxy-7β, 11-epoxycarabrane [20], except for the absence of a 6β-methoxy signal for C-6 in 1. These data indicated that one methoxy in 4, 8-dioxo-6β-hydroxyl-7β, 11-epoxycarabranewas replaced by a hydroxy in 1. This was referred by the 13C NMR spectrum (Table 2), where the methoxy signal also absence in 1 compared to δC 55.9 (-OCH3) in 4, 8-dioxo-6β-methoxy-7β, 11- epoxycarabrane. Furthermore, the 1H-1H COSY correlation of H-5/ H-6combined with the HMBC correlations from H-1 to C-5 and C-6 indicated that the hydroxyl located at C-6 (Fig. 2). Thus, the planar structure of 1 was disclosed.

|

Download:

|

Figure 2. Key 1H-1H COSY (  |

|

The relative configuration of 1 was assigned on the basis of the NOESY experiments. The NOESY correlation of H-2/H-5(H-15) indicated 3-oxobutyl group (CH3COCH2CH2-), H-5, and H-15 should be placed on the same face. The NOESY correlation of H-1/ H-6 indicated that H-1 and H-6 should be placed on the same face. In addition, a β-orientation for dimethyloxirane was suggested by the NOESY correlation of H-1/H-12. Thus, compound 1 was elucidated as the new carabrane-type sesquiterpene 4, 8-dioxo-6β- hydroxyl-7β, 11-epoxycarabrane.

4, 8- Dioxo-6β-hydroxyl-7α, 11-epoxycarabrane (2) was also obtained as a colorless oil. [α]D25 = +46.5 (c = 0.34, MeOH); which had the same molecular formula C15H22O4, as that of 2 on the basis of the HR-ESI-MS spectroscopic data analysis(m/z298.1468[M + Na]+). The IR spectrum of 2 indicated the same functionalities asin 1. In the 1H NMR spectrum, four methyl groups [δH 1.25 (s, 3H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.54(s, 3H), 2.12(s, 3H)], two protons of a cyclopropane [δH 0.65 (m, 1H), 1.04 (t, 1H, J = 4.7Hz)] were observed. In the 13C-NMR spectrum, two carbonyl carbons (δC 206.7, 208.1), three O-bearing carbons (δC 65.6, 66.5, 81.8), four methyls (δC 19.1, 19.2, 22.7, 31.1), three methylenes (δC 22.9, 43.6, 47.9) and other two methines (δC 25.5, 26.2), and one quaternary carbon (δC 21.1) were observed. As a result of comparing the1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data of 2 with those of 1 (Table 1), compound 2 was found to be a carabrane-type sesquiterpene related structurally to 1. The chemical shifts of all the carbon signals except for C-7 (d 69.7) and C-11 (d 62.5) in 2 were comparable with those of 1, which occurred at δC 66.9 for C-7 and 66.5 for C-11, respectively, in 1. On the basis of an analysis of the HMQC, HMBC, and 1H-1 H COSY spectra, the planar structure of 2 was deduced, which was identical to 1.

The relative configuration of 2 was assigned on the basis the NOESY experiments. The relative stereochemistry of 2 was very similar to that of 1 except the α-orientation for dimethyloxirane in 2 instead of their β-orientation in 1 according to the NOESY correlation of H3-12 and H-2/H-15. In addition, no correlations between H-12 and H-1 also confirmed an α-orientation for dimethyloxirane group (Fig. 3). Thus, compound 2 was identified as 4, 8-dioxo-6β-hydroxyl-7α, 11-epoxycarabrane (2).

Wenyujinin Q (3) was also obtained as a white amorphous powder. Compound 3 has the molecular formula C15H24O3(four degrees of unsaturation), as indicated by HR-ESI-MS and NMR data. The UV spectrum (252 nm) indicated the presence of an α-, β- unsaturated carbonyl moiety, and the IR spectrum showed bands corresponding to OH (3422 cm-1) and carbonyl (1669 cm-1) groups. In the 1H NMR spectrum, four methyl groups [δH 1.0 (d, 3H, 2.8), 1.17 (s, 3H), 1.91 (s, 3H), and 2.09 (s, 3H)] were observed. In the 13C-NMR spectrum, one carbonyl carbon (δC 202.8), two olefinic carbons (δC129.4, 149.9), two O-bearing carbons (δC 74.3, 81.7), four methylenes (δC 23.6, 27.6, 28.8, 50.7), two methines (δC 45.1, 58.8), and four methyls (δC 13.2, 23.9, 24.1, 32.6) were observed. Thus, compound 3 was a guaiane-type sesquiterpenes. The planar structure of 3 was disclosed by analyzing the HSQC, HMBC, and 1H-1H COSY NMR spectra (Fig. 2). The 1H-1H COSY correlation of H-1/H-2/H-3/H-4/H-14 indicated the presence of fragment (1) C-1-C-2-C-3-C-4-C-14. In the HMBC spectrum, H-12/H-13 showed correlations to C-7/C-11 and H-6correlations to C-7/C-8 indicated that the presence of fragment (2) an α, β-unsaturated carbonyl fragment. In addition, H-6 showed correlations to C-4/C-5 and H-8 showed correlations to C-1/C-10 indicated that fragment (1) and (2) linked by C-5 and C-9-C-10. C-15 location at C-10 was confirmed by HMBC correlation H-15 to C-1/C-10/C-9 (Fig. 3).

|

Download:

|

Figure 3. Key NOESY ( |

|

The relative configuration of 3 was assigned on the basis of the NOESY experiments. In the NOESY spectrum, the correlations of H-1/H-14/H-15 indicated that H-1, H3-14 and H3-15 should be placed on the same face. Thus, compound 3 was determined to be (1β, 4β, 5β, 10α) -5, 10-dihydroxy-7(11)-guaien-8-one.

Wenyujinin R (4) was obtained as a white amorphous powder. Compound 4 had the molecular formula C15H24O3(four degrees of unsaturation), as indicated by HR-ESI-MS and NMR data. The UV spectrum (252 nm) indicated the presence of an α, β-unsaturated carbonyl moiety, and the IR spectrum showed bands corresponding to hydroxyl (3422 cm-1) and carbonyl (1669 cm-1) groups. In the 1H NMR spectrum, four methyl groups [δH 1.08 (s, 3H), 1.14 (s, 3H), 1.80 (s, 3H), 1.86 (s, 3H)] were observed. In the 13C-NMR spectrum, one carbonyl carbon (δC 203.1), two olefinic carbons (δC 136.3, 140.0), two O-bearing carbons (δC 72.3, 79.6), four methylenes (δC 22.8, 29.1, 40.1, 60.9), two methines (δC 52.5, 56.7), and four methyls (δC 20.4, 21.9, 22.6, 22.6, ) were observed. Thus, compound 4 was a guaiane-type sesquiterpenes. Comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR data of 4 with 4, 10-epizedoarondiol [21] indicated that 4 possessed the same planar structure as 4, 10- epizedoarondiol. In the NOESY spectrum, the correlations of H-5 with Me-14/Me-15 indicated that H-5, Me-14, and Me-15 should be placed on the same face suggested that 4 should be a 10-epimer of 4, 10-epizedoarondiol. Thus, the compound 4 was determined to be (1α, 4α, 5β, 10α)-4, 10-dihydroxy-7(11)-guaien-8-one.

The structures of known compounds 5 - 13 were identified by comparison of their 1H/13C NMR spectra and [α]D25 data with those in the literature.

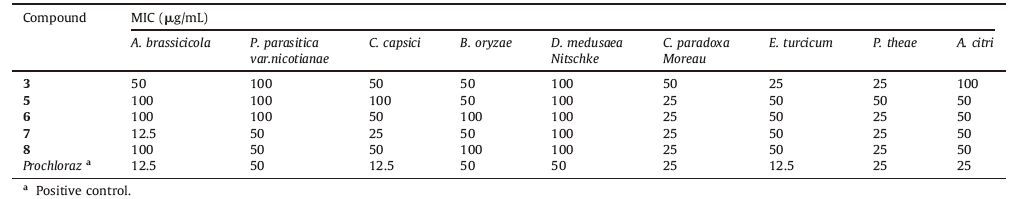

The antibacterial activities of all compounds were determined against seven terrestrial pathogenic bacterias: M. tetragenus, E. coli, S. albus, B. cereus, S. aureus, Kocuria rhizophila, and B. subtilis. The results indicated that compounds 3, 8, and 12 show weak antibacterial activity to E. coli, 2 and 11 to S. aureus, 7 and 11 to B. subtilis, 4 and 11 show to B. cereus, and 11 to M. luteus with the same MIC value at 10 mg/mL, respectively. The antifungal activities of all compounds were determined against nine phytopathogenic fungal: A. brassicicola, P. parasitica var. nicotianae, C. capsici, B. oryzae, D. medusaea Nitschke, C. paradoxa moreau, E. turcicum, P. theae, and A. citri. The results (Table 3) indicated that 3, 5-8 exhibited strong broad-spectrum antifungal activities against those nine fungal and antifungal activities were better than antibacterial activities in these assays.

|

|

Table 3 The antifungal activity of compounds 3, 5-8 (in vitro). |

4. Conclusion

In this study, four new sesquiterpenoids (1-4), and nine known sesquiterpenoids (5-13) were isolated from the C. wenyujin dreg. Their structures and relative configurations were elucidated using 1D, 2D NMR, and HR-ESI-MS data. All the compounds were isolated for the first time from the C. wenyujin dreg and evaluated for their antibacterial and antifungal activities. Compounds 3, 5-8 exhibited strong broad-spectrum antifungal activities against tested nine pathogenic fungi. Their pronounced bioactivities implied that these sesquiterpenoids are worth of further studies.

AcknowledgmentThis work was supported by the Program of Hainan provincial key science and technology (No. ZDXM20130059) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (No.213020).

| [1] | The State Pharmacopoeia Commission of PRC, Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China, China Medical Science and Technology Press, Beijing, China, 2015, pp. 274-275. |

| [2] | J.Y. Dong, X.Y. Ma, X.Q. Cai, et al. Sesquiterpenoids from Curcuma wenyujin with anti-influenza viral activities. Phytochemistry 85 (2013) 122–128. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.09.008 |

| [3] | Q. Xia, Z.G. Huang, S.P. Li, et al. The experiment study of the antivirus effects of zedoary oil on influenzavirus and respiratory syncytial virus. Chin. Pharm. Bull. 3 (2004) 357–358. |

| [4] | Y. Tang, X.H. Li. Inhibitory effects of zedoray rhizome abstracts on hepatic cell line HepG2 and their mechanisms. Chin. Pharm. Bull. 23 (2007) 790–794. |

| [5] | H.Y. Choi. Antioxidant activity of Curcuma longa L. novel foodstuff. Mol. Cell Toxicol. 5 (2009) 237–242. |

| [6] | P.S. Vankar. Effectiveness of antioxidant properties of fresh and dry rhizomes of Curcuma longa (long and short varieties) with dry turmeric spice,. Int. J. Food Eng. 4 (2008) . |

| [7] | C. Tohda, N. Nakayama, F. Hatanaka, K. Komatsu. Comparison of anti-inflammatory activities of six Curcuma Rhizomes:a possible curcuminoid-independent pathway mediated by Curcuma phaeocaulis Extract. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 3 (2006) 255–260. DOI:10.1093/ecam/nel008 |

| [8] | G.P. Yin, L.C. Li, Q.Z. Zhang, et al. iNOS inhibitory activity of sesquiterpenoids and a monoterpenoid from the rhizomes of Curcuma wenyujin. J. Nat. Prod. 77 (2014) 2161–2169. DOI:10.1021/np400984c |

| [9] | The State Pharmacopoeia Commission of PRC, Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China, China Medical Science and Technology Press, Beijing, China, 2010p. 388. |

| [10] | T.Y. Yan, Q.J. Zheng, G.T. Zhou, et al. Study on ezhu intravenous injection in treating infantile respiratory syncytial Virus Pneumonia and its therapeutical mechanism. Chin. J. Integr. Tradit. West. Med. 711-715 (1992) 707. |

| [11] | G.P. Yin, Q.Z. Zhang, Y.W. An, et al. Advance in chemical constituents and pharmacological activity of Curcuma wenyujin. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 37 (2012) 3354–3360. |

| [12] | M. Kuroyanagi, A. Ueno, K. Ujiie, S. Sato. Structures of sesquiterpenes from Curcuma aromatica SALISB. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 35 (1987) 53–59. DOI:10.1248/cpb.35.53 |

| [13] | Y.W. Ge, H.M. Gao, W.H. Wang, Z.M. Wang. Studies on chemical constituents in Guiyujin (Report I). Chin. Pharm. J. 42 (2007) 822–824. |

| [14] | M. Kuroyanagi, A. Ueno, K. Koyama, S. Natori. Structures of sesquiterpenes from Curcuma aromatica SALISB. Ⅱ.:studies on minor sesquiterpenes. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 38 (1990) 55–58. DOI:10.1248/cpb.38.55 |

| [15] | Y. Liu, J.H. Ma, Q. Zhao, et al. Guaiane-type Sesquiterpenes from Curcuma phaeocaulis and their inhibitory effects on nitric oxide production. J. Nat. Prod. 76 (2013) 1150–1156. DOI:10.1021/np400202f |

| [16] | K. Harimaya, J.F. Gao, T. Ohkura, et al. A series of sesquiterpenes with a 7aisopropyl side chain and related compounds isolated from Curcuma wenyujin. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 39843 (1991) –853. |

| [17] | N. Sakui, M. Kuroyanagi, Y. Ishitobi, et al. Biotransformation of sesquiterpenes by cultured cells of Curcuma zedoaria. Phytochemistry 31 (1992) 142–147. |

| [18] | G.G. Qiu, P.C. Yan, W.W. Shao, et al. Two new sesquiterpenoids including a sesquiterpenoid lactam from Curcuma wenyujin. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 61 (2013) 983–986. DOI:10.1248/cpb.c13-00405 |

| [19] | L.X. Wang, Z.W. Deng, K.X. Huang, W.H. Lin. Sesquiterpenes from stems and leaves of Curcuma wenyujin. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 7 (2008) 785–788. |

| [20] | J. Xu, P. Zhang, Z.J. Ma, et al. Two carabrane-type sesquiterpenes from Vladimiria souliei. Phytochem. Lett. 2 (2009) 204–206. DOI:10.1016/j.phytol.2009.08.001 |

| [21] | A. Saifudin, K. Tanaka, S. Kadota, Y. Tezuka. Sesquiterpenes from the rhizomes of Curcuma heyneana. J. Nat. Prod. 76 (2013) 223–229. DOI:10.1021/np300694a |

| [22] | C.G. Pierce, P. Uppuluri, A.R. Tristan, et al. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat. Protoc. 3 (2008) 1494–1500. DOI:10.1038/nprot.2008.141 |

2016, Vol. 27

2016, Vol. 27