Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) is one of the five general plastics, widely applied in industry, agriculture and building materials. Vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) is mainly used for producing PVC by self-polymerization. At present, VCM is generally synthesized via the dehydrochlorination of dichloroethane (the ethylene-based process) or the hydrochlorination of acetylene (the acetylenebased process) in industry [1, 2]. Limited by the raw material cost and the characteristics of energy structure, the hydrochlorination of acetylene has received much attention in countries with large reserves of coal [3]. For instance, currently PVC production through the acetylene-based process accounts for about 70% of the total PVC production capacity in China.

In the industrial acetylene-based process, VCM is produced by reacting acetylene with anhydrous hydrogen chloride over activated carbon-supported mercuric chloride catalyst [4]. This reaction is strongly exothermic and highly selective to vinyl chloride at the optimum reaction temperature of 170-180 ℃ [5]. However, the loss of mercuric chloride from the surface of activated carbon leads to the deactivation of mercuric chloride catalyst under the reaction conditions [4, 6]. Due to the low volatility of mercuric chloride, the loss of HgCl2 can be accelerated by the strong reaction heat [7]. For the spent high-mercury catalyst, the content of HgCl2 decreases from the original 10%-12% to less than 5% [8]. The loss of highly toxic HgCl2 can lead to the increase of cost and is harmful to the environment and human health. Due to the above disadvantages of mercuric chloride catalyst, researchers have tried to find alternatives, such as Au3+ [9-11], Pd2+ [12], Ru3+ [13], Bi3+ [14], etc. However, these nonmercury catalysts cannot simultaneously satisfy the requirements of high activity and good stability as industrial catalysts. For instance, Au3+ with high intrinsic activity is considered to be the most promising catalyst to replace mercuric chloride catalyst [15], but the Au3+ catalyst has not yet been applied industrially for acetylene hydrochlorination due to its poor catalytic stability and high cost [16, 17]. Therefore, at present, activated carbonsupported mercuric chloride catalyst is still chosen to produce VCM by most of VCM producers. In order to reduce the usage of mercuric chloride in PVC industry, some low-mercury catalysts with HgCl2 loading of about 5%-6% have been developed under the premise of keeping the equivalent catalytic activity and stability to high-mercury catalysts [8, 18].

It is worth noting that loss of mercuric chloride and the deactivation phenomenon also exist in the operating cycle of lowmercury catalyst [8]. Thus, other additives are necessary to improve the stability of low-mercury catalysts. In this paper cesium chloride (CsCl) was selected as an additive for the catalyst, because CsCl can interact with HgCl2 to form a series of new compounds, CsxHgyClx+2y [19]. In the structures of CsxHgyClx+2y, Hg atoms bond with multiple Cl atoms and exist in the forms of [HgmCln](n-2m)- ionic groups, which enhance the thermal stability of Hg-Cs/AC catalyst. The as-prepared low-mercury catalyst Hg- Cs/AC achieved better acetylene conversion and stability than the catalyst without CsCl under the reaction conditions.

2. Experimental 2.1. Pretreatment of activated carbon supportA commercial activated carbon NORIT ROX 0.8 (pellets of 0.8 mm diameter and 5 mm length) was selected as the support. The activated carbon was first washed with concentrated nitric acid solution (HNO3, 65%-68%) at room temperature for 1 h to remove the contained impurities. Then the activated carbon was collected by filtration and washed with deionized water to neutral and dried at 110 ℃ for 12 h in the air atmosphere.

2.2. Catalyst preparationIn order to achieve 4 wt% HgCl2 loading, the method of incipient wetness impregnation was employed to prepare the catalysts as follows: First, 0.2 g of HgCl2 (GR, ≥99.9%) and 0.19 g of CsCl (AR, ≥99%) were dissolved in 9 mL of aqua regia simultaneously. Then, the HgCl2-CsCl solution was added continuously to 5 g of activated carbon. Finally, after placed overnight, the catalyst was dried at 80 ℃ for 12 h in the air. The catalyst was labeled as Hg-Cs/AC. The same procedure was used to prepare the Hg/AC catalyst without CsCl.

2.3. Sublimation rate measurements of HgCl2The average sublimation rate measurements of HgCl2 were carried out as follows: 0.6 g of fresh catalyst was set into a tubular reactor (Φ 10 mm × 400 mm) with temperature fluctuation controlled within ±1 ℃ and 11 mL min-1 of nitrogen was fed into the reactor for 12 h before the catalyst was taken out to be analyzed. The content of HgCl2 in the catalyst was analyzed by titration with C5H10NS2Na: After the catalyst was ground, screened with 80 mesh, and dried to constant weight, 0.5 g of the sample was put into a 250 mL flask with a reflux condenser, and 10 mL of aqua regia and 10 mL of 10 wt% NaCl solution were added before the mixture was heated and boiled for 15 min. The diluted mixture was filtered and titrated with a standard C5H10NS2Na solution. Considering the easy sublimation of mercuric chloride and the high temperature during the drying process, the real contents of HgCl2 in fresh catalysts were determined by the same titration method above.

2.4. Catalyst characterizationX-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the catalysts were conducted on a PANalytical X’Pert diffractometer using a Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.1541 nm) in a scanning range of 2θ = 10-808 that was operated at a voltage of 40 kV and a current of 40 mA. The morphology and components of the catalysts was characterized using a transmission electronic microscope (TEM, Philips-FEI Tecnai G2 F30 S-Twin) equipped with a high-angle annular darkfield (HAADD) attachment and EDX spectrometer.

2.5. Catalytic performance evaluationCatalytic performance was carried out in a fixed bed reactor (i.d. 10 mm). The temperature of the reactor was regulated by an AI-808P temperature controller (Xiamen Yudian Automation Technology Co., Ltd.). At first, nitrogen was fed into the reactor to remove water and air in the reaction system. Then, when the reactor was heated to 170 ℃, hydrogen chloride (HCl, 1 bar) gas was passed through the reactor with a flow rate of 6 mL min-1 controlled by a calibrated mass flow controller (Beijing Sevenstar Electronics Co., Ltd.) to activate the catalyst (0.82 g) for 0.5 h. Next, acetylene (C2H2, 1 bar) was fed through another calibrated mass flow controller with a flow rate of 5 mL min-1 and mixed with HCl before passing through the reactor. Here, the gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of C2H2 is 180 h-1. The exit gas mixture was passed through an absorption bottle containing NaOH solution to remove the excess HCl. The composition of the treated gas mixture was detected using an online gas chromatography (Zhejiang Fuli Analytical Instruments Co., Ltd.) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID). Chromatographic separation and identification of the composition was analyzed using a Porapak N packed column (6 ft × 1/800 stainless steel). Acetylene conversion and VCM selectivity were defined by the following equations:

| ${{\rm{C}}_{\rm{2}}}{{\rm{H}}_{\rm{2}}}{\rm{Conv}}{\rm{.}}\left( \% \right) = \left( {1 - {{{F_A}} \over {{F_{A0}}}}} \right) \times 100\% $ | (1) |

| $VCMSel.\left( \% \right) = \left( {{{{F_{{\rm{VCM}}}}} \over {1 - {F_A}}}} \right) \times 100\% $ | (2) |

In the above equations, FA0, FA, and FVCM represent the volume fraction of acetylene in the raw gas, the volume fraction of remaining acetylene in the product mixture gas, and the volume fraction of VCM in the product mixture gas, respectively.

In order to study the thermal stability of the catalysts, the temperature tolerance tests were carried out under different reaction temperatures, as follows: At an acetylene gas hourly space velocity of 180 h-1, the reaction started under an initial temperature of 130 ℃. After reacting for 8 h every time, the temperature was raised by 40 ℃. When the reaction finished at 250 ℃, the reaction temperature was regulated down to 170 ℃, allowing the reaction mixture to stir for 8 h.

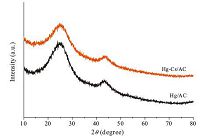

3. Results and discussionSome characterizations were carried out to investigate the crystal phases, morphology and elements distribution of the asprepared catalysts, Hg-Cs/AC and Hg/AC. The X-ray diffraction patterns of the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst and the Hg/AC catalyst are given in Fig. 1. It is obvious that there are no detectable reflections of HgCl2, CsCl or their complex, CsxHgyClx+2y, with only the amorphous peaks of activated carbon support. It proved that the active components are highly dispersed on the surface of activated carbon. It is common that when supported catalysts are characterized by XRD, the diffraction peaks of the active components cannot be found on the XRD patterns. In general, it is suggested that the active components in the catalyst are in such a small quantity or an amorphous state that they evade the detection by X-ray diffraction. However, in many catalysts the active components are neither in a small quantity nor likely to form an amorphous phase, still their characteristic peaks do not appear in the X-ray patterns. Xie and Tang [20] proposed that if the active component of the catalyst is a compound (e.g. salts or oxides of transition metals) instead of metals and its quantity is insufficient to cover the surface of the support, it often disperses as a monolayer or submonolayer, because the ions or molecules of the active component combine strongly with the surface ions or groups of the support. Xie [21] characterized the vinyl chloride catalyst, 10% Hg/AC, and failed to give characteristic peaks of HgCl2 in XRD patterns. HgCl2 is a molecular crystal with low melting point and the weak bonding between HgCl2 molecules is easily broken to facilitate the combination of HgCl2 molecules with the polar groups or sites with unsaturated valence on the surface of activated carbon [20]. LiCl, NaCl and KCl can disperse spontaneously as a monolayer onto the surface of g-Al2O3 support after heat treatment, respectively [21]. Because LiCl, NaCl, KCl and CsCl all belong to alkali metal chlorides, it is possible that CsCl can disperse as a monolayer onto the surface of activated carbon.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 1. XRD patterns of the Hg/AC and Hg–Cs/AC catalysts. | |

In order to further study the distribution of the elements of Cs and Hg on the surface of activated carbon, HR-TEM and mapping techniques were introduce to observe the morphology of the Hg- Cs/AC catalyst. As shown in Fig. 2a and b, there are no obvious nanoparticles but the clear and regular lattice fringes on the surface of activated carbon. The characterization of HR-TEM verifies that the XRD pattern is reasonable and the active species dispersed as a monolayer or submonolayer on the surface of activated carbon. The spacing of lattice fringes is 0.2768 nm, not consistent with the spacing of lattice fringes of CsCl or HgCl2. This value is very close to the spacings of (2 0 2) crystal planes of CsHgCl3 (JCPD 00-021-0848) , (2 0 4) crystal planes of Cs2HgCl4 (JCPD 00-089-6697) and (-1 2 1) crystal planes of CsHg2Cl5 (JCPD 00-047-1507) , which are 0.2715 nm, 0.2765 nm and 0.2794 nm, respectively. It implies that CsCl and HgCl2 may react with each other forming cesium-mercuric chlorides. The mapping photographs of the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst in Fig. 2c display that Cs, Hg and Cl elements were homogeneously distributed on the surface of activated carbon. It illustrates that there are some interactions between CsCl and HgCl2. It has been reported [19, 22] that CsCl and HgCl2 can form five types of cesium mercuric chlorides: Cs3HgCl5, Cs2HgCl4, CsHgCl3, CsHg2Cl5 and CsHg5Cl11. The structure of Cs3HgCl5 consists of Cs+, Cl- and distorted tetrahedral [HgCl4]2- [23]. Cs2HgCl4 is composed of Cs+ and [HgCl4]2- tetrahedral anion [24]. CsHgCl3 has a cubic perovskite-type structure [25, 26], in which every Hg atom coordinates with 6 Cl atoms, forming a distorted HgCl6 octahedral [27, 28]. For CsHg2Cl5, its crystal structure consists of Cs+ and [Hg2Cl5]- ions [29]. And CsHg5Cl11 contains Cs+, [Hg4Cl9]- and an additional HgCl2 molecule [30]. In the above five compounds, one Hg atom generally coordinates with more than two Cl atoms, existing in the form of ionic groups, different from the HgCl2 molecule in mercury chloride.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 2. (a) TEM image of the Hg–Cs/AC catalyst. (b) HR-TEM image of the Hg–Cs/AC catalyst. (c) HAADD image together with the XEDS mapping of the Hg–Cs/AC catalyst. | |

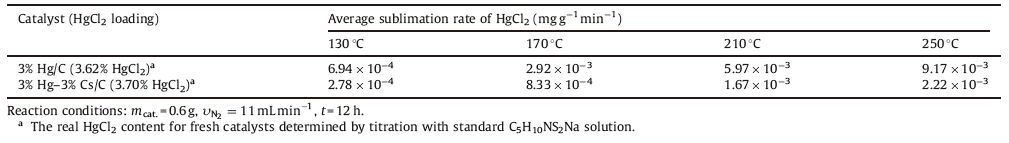

The sublimation of HgCl2 for the two catalysts under different temperatures was compared, listed in Table 1. At 130 ℃, the average sublimation rate of HgCl2 for Hg-Cs/AC catalyst is 2.78 × 10-4 mg g-1 min-1, which is about 40% of the rate of Hg/AC catalyst. With the temperature increasing from 130 ℃ to 250 ℃, the sublimation of HgCl2 was accelerated for both catalysts. The average sublimation rate of HgCl2 for Hg-Cs/AC catalyst is 25% of that of Hg/AC catalyst under 250 ℃. With the temperature increasing, the difference of the HgCl2 sublimation rates between the two catalysts became obvious, particularly under elevated temperatures. These data indicate that the addition of CsCl inhibits the sublimation of HgCl2 from the surface of activated carbon significantly.

|

|

Table 1 Effect of CsCl on the average sublimation rate of HgCl2 under different temperatures. |

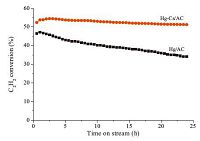

The Hg-Cs/AC and Hg/AC catalysts were evaluated under fixed reaction conditions at 170 ℃, an acetylene gas hourly space velocity (C2H2) of 180 h-1, and a fed volume ratio V(HCl)/V(C2H2) of 1.2. The comparison of the catalytic performance of the asprepared Hg-Cs/AC and Hg/AC catalysts for acetylene hydrochlorination is shown in Fig. 3. It can be seen that the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst exhibited a higher initial acetylene conversion of 52.35% than the 46.57% achieved using the Hg/AC catalyst. The real contents of HgCl2 in the Hg-Cs/AC and Hg/AC catalysts were 3.72 wt% and 3.67 wt%, respectively, slightly less than the theoretical content of HgCl2. The difference of the initial activity between the two catalysts was unlikely a result of the HgCl2 loading. It indicated that the addition of CsCl into the Hg/AC catalyst can improve the initial catalytic activity. Furthermore, the highest acetylene conversion for the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst is 54.44% at the reaction time of 2.5 h while the highest acetylene conversion for the Hg/AC catalyst is 47.22% at the reaction time of 1 h. Unfortunately, the acetylene conversion for the Hg/AC catalyst evidently started to decrease after reacting for 1 h. And the acetylene conversion showed continuous slowdown and finally decreased to 34.03% at the reaction time of 24 h. This deactivation is mainly due to the loss of HgCl2 species by sublimation from the surface of the activated carbon in the process of reaction [7]. In contrary to the Hg/AC catalyst, the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst exhibited more stable catalytic activity. Even evaluated after 24 h, the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst exhibited an acetylene conversion of 51.23%, a moderate reduction of 3.21%. It illustrated that there was almost no sublimation of HgCl2 from the surface of activated carbon under the above reaction conditions.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 3. Catalytic performance of Hg/AC and Hg–Cs/AC for acetylene hydrochlorination. Reaction conditions: T = 170 ℃, VC2H2 = 5mL min-1, VHCl = 6 mL min-1, GHSV(C2H2) = 180 h-1. | |

The results of the temperature tolerance tests of the catalysts were represented in Fig. 4. For the Hg/AC catalyst, when the reaction temperature increased from 130 ℃ to 170 ℃, 210 ℃, and 250 ℃ gradually, the acetylene conversion was improved from 15% to 30%, 59%, and 66%, respectively. Nevertheless, the Hg/AC catalyst gave an acetylene conversion of 20% while the temperature was down to 170 ℃, lower than the 30% obtained at the initial 170 ℃. In addition, the acetylene conversion decreased slowly in every stage of the reaction. For the Hg-Cs/C catalyst, the acetylene conversion was 27%, 50%, 68% and 72% at 130 ℃ to 170 ℃, 210 ℃, and 250 ℃, respectively. Meanwhile, when the reaction temperature was lowered to 170 ℃, the acetylene conversion was still around 50%, almost consistent with the former value. It suggested that the stability of the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst is better than that of the Hg/AC catalyst under the reaction conditions and the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst can be used under higher reaction temperatures, having larger capability of C2H2 conversion. All above results indicated that the catalytic performance of the Hg-Cs/C catalyst is better than that of the Hg/AC catalyst and the addition of CsCl not only improves the initial activity of the catalyst, but also inhibits the sublimation of HgCl2 from activated carbon support, strengthening the stability of the low-mercury catalyst. On the one hand, this promoting effect is attributed to the fact that one Hg atom bonds with multiple Cl atoms, forming [HgmCln](n-2m)- ionic groups in the structures of cesium-mercuric chlorides. On the other hand, it is possible that the introduction of Cs+ ions to Hg/AC catalyst may contribute to the improvement of the catalytic performance of the catalyst. Li et al. [31] proposed that adding CsCl into Au/C catalyst stabilized the catalytically active Au3+ species in the hydrochlorination of acetylene, inhibiting the reduction of Au3+ to Au0. They claimed that there was a synergistic effect between Au and Cs existing in Au-Cs/AC catalysts and a weak polarization of Cs+ to Cl- due to the large ionic radius of Cs+. This begs a detail investigation about the interaction of Cs atoms with Hg atoms and the effect of Cs+ on Hg- Cl bond and this work is currently underway.

|

Download:

|

| Figure 4. The temperature tolerance tests of low-mercury catalysts for acetylene hydrochlorination ((a) Hg/AC; (b) Hg–Cs/AC). Reaction conditions: VC2H2 = 5mL min-1, VHCl = 6 mL min-1, GHSV(C2H2) = 180 h-1. | |

4. Conclusion

CsCl was selected as a promoter for the low-mercury catalyst and its role in mercuric chloride catalyst was studied. The results indicated that the addition of CsCl inhibits the loss of HgCl2 from the surface of activated carbon. For the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst, HR-TEM and EDX characterizations indicated that CsCl and HgCl2 interacted with each other and formed the cesium-mercuric chlorides, CsxHgyClx+2y during the catalyst preparation process. In the structure of CsxHgyClx+2y, one Hg atom coordinates with multiple Cl atoms, forming an ionic group that no longer exists in the form of HgCl2 molecules. The conversion of the existing form of Hg atoms from HgCl2 to CsxHgyClx+2y affects the sublimation behavior of mercury element. In the process of acetylene hydrochlorination, the Hg-Cs/AC catalyst has higher initial activity and better longterm stability than the Hg/AC catalyst under reaction conditions. This suggests that the active sites in which one Hg atom bonds with multiple Cl atoms and introduction of Cs+ may contribute to the better catalytic efficiency and stability of Hg/AC catalyst for acetylene hydrochlorination. Furthermore, this provides us a new direction in designing new mercury chloride catalyst with low mercury loading and high catalytic performance.

| [1] | Q.S. Han, F. Sun. Contrast analysis on PVC produced by ethylene method and acetylene method. Polyvinyl Chloride 37 (2009) 5–7. |

| [2] | F.Z. Xin. Contrast of vinyl chloride production processes. Yunnan Chem. Technol. 37 (2010) 65–70. |

| [3] | X.B. Wei, H.B. Shi, W.Z. Qian, et al. , Gas-phase catalytic hydrochlorination of acetylene in a two-stage fluidized-bed reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 48 (2009) 128–133. |

| [4] | G.J. Hutchings, D.T. Grady. Hydrochlorination of acetylene: the effect of mercuric chloride concentration on catalyst life. Appl. Catal. 17 (1985) 155–160. |

| [5] | J.L. Zhang, N. Liu, W. Li, B. Dai. Progress on cleaner production of vinyl chloride monomers over non-mercury catalysts. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 5 (2011) 514–520. |

| [6] | G.J. Hutchings, D.T. Grady. Effect of drying conditions on carbon supported mercuric chloride catalysts. Appl. Catal. 16 (1985) 411–415. |

| [7] | J.B. Agnew, H.S. Shankar. Catalyst deactivation in acetylene hydrochlorination. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. 25 (1986) 19–22. |

| [8] | Z.Q. Chen, X.Y. Ma. Application of environmental low-mercury catalyst. China Chlor-Alkali 9–11. |

| [9] | G.J. Hutchings. Catalysis: a gold future. Gold Bul. 29 (1996) 123–130. |

| [10] | W. Wittanadecha, N. Laosiripojana, A. Ketcong, et al., Preparation of Au/C catalysts using microwave-assisted and ultrasonic-assisted methods for acetylene hydrochlorination, Appl. Catal., A: Gen. 475 (2014) 292-296. |

| [11] | H.Y. Zhang, B. Dai, W. Li, et al. , Non-mercury catalytic acetylene hydrochlorination over spherical activated-carbon-supported Au-Co(III)-Cu(II) catalysts. J. Catal. 316 (2014) 141–148. |

| [12] | Q.L. Song, S.J. Wang, B.X. Shen, J.G. Zhao. Palladium-based catalysts for the hydrochlorination of acetylene: reasons for deactivation and its regeneration. Pet. Sci. Technol. 28 (2010) 1825–1833. |

| [13] | Y.F. Pu, J.L. Zhang, L. Yu, Y.H. Jin, W. Li. Active ruthenium species in acetylene hydrochlorination, Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 488 (2014) 28–36. |

| [14] | K. Zhou, J.C. Jia, X.G. Li, et al. , Continuous vinyl chloride monomer production by acetylene hydrochlorination on Hg-free bismuth catalyst: from lab-scale catalyst characterization, catalytic evaluation to a pilot-scale trial by circulating regeneration in coupled fluidized beds. Fuel Process Technol. 108 (2013) 12–18. |

| [15] | G.J. Hutchings. Vapor phase hydrochlorination of acetylene: correlation of catalytic activity of supported metal chloride catalysts. J. Catal. 96 (1985) 292–295. |

| [16] | M. Conte, A.F. Carley, C. Heirene, et al. , Hydrochlorination of acetylene using a supported gold catalyst: a study of the reaction mechanism. J. Catal. 250 (2007) 231–239. |

| [17] | J. Zhao, J.T. Xu, J.H. Xu, et al. , Enhancement of Au/AC acetylene hydrochlorination catalyst activity and stability via nitrogen-modified activated carbon support. Chem. Eng. J. 262 (2015) 1152–1160. |

| [18] | X.L. Zhang, J. Zhou, G.D. Li, Progress on the research of low-immobilized mercury catalyst application system, China Chlro-Alkali (2013) 17-19. |

| [19] | V.V. Kirilenko, V.I. Pakhomov, A.Y. Mikhajlova, R.Sh. Lotfulin, M.V. Simonov, A.V. Medvedev, R.N. Shchelokov, The CsCl-HgCl2 system, Neorg. Mater. 20 (1984) 1911-1915. |

| [20] | Y.C. Xie, N.F. Yang, Y.J. Liu, Y.Q. Tang. Spontaneous dispersion of some active components onto the surfaces of carriers. Sci. Sin. 26 (1983) 337–350. |

| [21] | Y.C. Xie, Y.Q. Tang. Spontaneous monolayer dispersion of oxides and salts onto surfaces of supports: applications to heterogeneous catalysis. Adv. Catal. 37 (1990) 1–43. |

| [22] | H.L. Wells. On caesium-mercuric halides. Am. J. Sci. 44 (1892) 221–236. |

| [23] | W. Clegg, M.L. Brown, L.J.A. Wilson, Tricaesium tetrachloromercurate(II) chloride, Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 32 (1976) 2905-2906. |

| [24] | B. Bagautdinov, J. Luedecke, M. Schneider, S. Van Smaalen, Disorder in the crystal structure of Cs2HgCl4 studied by the maximum entropy method, Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 54 (1998) 626-634. |

| [25] | H.F. McMurdie, J. De Groot, M. Morris, H.E. Swanson, Crystallography and preparation of some ABCl3 compounds, J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 73A (1969) 621-626. |

| [26] | L. Liu, W.C. Lu, N.Y. Chen. On the criteria of formation and lattice distortion of perovskite-type complex halides. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 65 (2004) 855–860. |

| [27] | D.E. Scaife. Chlorine nuclear quadrupole resonance in mercury chlorides and complex chlorides. Aust. J. Chem. 24 (1971) 1753–1770. |

| [28] | O. Albarski, H. Hillebrecht, H.W. Rotter, G. Thiele, Über Caesiumtrichloromercurat( II) CsHgCl3: Lösung einer komplexenÜberstruktur und Verhalten unter hohen Drücken, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 626 (2000) 1296-1304. |

| [29] | V.I. Pakhomov, A.V. Goryunov, I.N. Ivanova-Korfini, A.A. Boguslavskij, R.Sh. Lotfulin. Cheminform abstract: crystal structure of CsHg2Cl5. Cheminform 22 (1991) 9. |

| [30] | D.A. House, W.T. Robinson, V. McKee, Chloromercury(II) anions, Coord. Chem. Rev. 135-136 (1994) 533-586. |

| [31] | J. Zhao, J.T. Xu, J.H. Xu, et al. , Activated-carbon-supported gold-cesium(I) as highly effective catalysts for hydrochlorination of acetylene to vinyl chloride. Chem-PlusChem 80 (2015) 196–201. |

2016, Vol. 27

2016, Vol. 27