2 Laboratory of Printable Functional Nanomaterials and Printing Electronics, School of Printing and Packaging, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China;

3 Department of Physics and Materials Science, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR 999077, China

In contrast to other power sources,LIBs have attracted much attention for various applications,from portable devices to electric cars,due to their low-cost,long cycle life,high stability and power density. The electrode materials of LIBs are important components to decide the overall performance of the LIBs. Generally,graphite is commonly used as the anode for commercial LIBs. However,the low specific capacity of graphite (theoretically 372 mAh g-1) hinders the development and application of LIBs [1, 2]. Therefore, it is essential to develop new electrode materials for the fabrication of high-performance LIBs.

As an important n-type band gap semiconductor,tin dioxide (SnO2) has been considered as an ideal material to replace graphite due to its high specific capacity (782 mAh g-1) and safe and easy preparation. However,SnO2 electrodes usually come across the problem of poor cycle performance due to large volume expansion that produces large internal stress and leads to electrode pulverization during the charge-discharge process [3, 4]. Currently, there are three primary methods to improve the cycle performance of SnO2 as LIB anode materials: First the design of nanoscale materials that can accommodate large volume changes. In this regard,SnO2 nanoparticles (NPs) with different sizes using various approaches as anode materials for LIBs have been widely reported [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. Second is the fabrication of unique structures to improve cyclic capacity retention. For example,void spaces in hollow and mesoporous nanostructures can inhibit the volume change and thus elevate the cyclic capacity [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Third is the synthesis of core-shell heterostructure materials to elevate the stability of core materials. For instance,combining SnO2 with other materials such as carbon and graphene to form SnO2/C heterostructures [18]. For example,Lou et al. have prepared hollow SnO2 nanostructures (500 nm) with 500 mAh g-1 cycle capacity over 40 cycles at 0.2 C current density [19]. The as-prepared SnO2 NPs cannot support the high current density which results in the poor cycling performance during the charge-discharge process. Subsequently,Lou et al. synthesized a SnO2@C hollow composite (200 nm) for application in LIBs. The product showed better cycling performance (600 mAh g-1) than pure SnO2 nanospheres (300 mAh g-1) [20]. Carbon decoration for anode and cathode materials has been proven to improve the electronic conductivity of electrodes [21, 22]. Indeed,composite nanomaterials have been used as electrode materials in LIBs due to enhanced electrical conductivity and reduced internal stress,which both improve the total electrical performance of LIBs [18, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Therefore,it is better to combine the small SnO2 NPs with other materials to protect the inner SnO2 NPs. However,the large size of SnO2 would cause lower cycling performance at high current density.

Herein,a well-defined sub-100 nm carbon coated hollow SnO2 nanoparticle has been designed and fabricated by a facile two-step hydrothermal method without the presence of any surfactants. As shown in Scheme 1,carbon coating is realized via hydrothermal treatment of low-cost glucose,and the whole synthesis process is environmentally benign. As-synthesized hollow SnO2@C NPs satisfy the aforementioned advantages to improve the cycle performance. The as-obtained sub-100 nm hollow SnO2@C NPs have been applied as anode materials for LIBs. The sub-100 nm hollow SnO2@C nanoparticle is a promising candidate for the fabrication of high capacity,low cost,and environmentally safe anode materials for LIBs.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme. 1.The synthesis process of sub-100 nm hollow SnO2@C NPs. | |

Potassium stannate trihydrate (K2SnO3.3H2O) was purchased from Shanghai Jingchun Chemical Reagent Co.,Ltd. Ethanol (C2H5OH),urea (CO(NH2)2),ethylene glycol (EG),and glucose (C6H12O6) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. All the materials were used as received and without further purification in the whole experimental process.

2.2. Synthesis of sub-100 nm hollow SnO2 nanoparticlesAccording to our previous report [29],typically,0.6 g of potassium stannate trihydrate were dissolved in 50 mL of EG through the ultrasonic method,and then 30 mL of urea aqueous solution (0.4 g of urea) was added. Then,the mixture was transferred into a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave (100 mL) and heated at 170 ℃ in a furnace for 24 h. After the autoclave cools down to room temperature,the products were collected via centrifugation and washed several times by deionized water and ethanol,and then dried at 80 ℃ under vacuum. In a single batch of experiments,more than 0.2 g of hollow SnO2 nanoparticles could be prepared.

Synthesis of hollow SnO2@C nanoparticles: briefly,0.4 g of asprepared hollow SnO2 NPs and 4 g of glucose were re-dispersed in ethanol/H2O solution. After stirring,the solution was transferred into a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave (100 mL) and heated at 180 ℃ for 8 h. The as-prepared products were collected via centrifugation and washed several times by H2O and ethanol,and then dried at 80 ℃ in air. Subsequently,the products were annealed at 450 ℃ for 4 h under argon with a heating rate of 5 ℃ min-1.

2.3. CharacterizationTransmission electron microscopy (TEM),selected area electron diffraction (SAED) and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) were carried out on a JEOL JEM-2100F transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Raman measurement was performed by a HORIBA Jobin Yvon LabRAM HR spectroscope using 488 nm excitation wavelength. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was recorded on a D/ruanx2550PC (Japan) using Cu Ka radiation (l = 0.1542 nm) operated at 40 kV and 40 mA and at a scan rate of 0.058 s-1. Thermo gravimetric analysis was performed on an SNTQ600 thermo gravimetric analyzer.

2.4. Electrochemical measurementsIn preparation of the coin cell battery,N-methyl pyrrolidinone (NMP) slurry consisting of 80 wt% hollow SnO2 or SnO2@C powders mixed with conductive agents and binder was coated onto a Cu foil. Pure lithium foil was used as the counter electrode,and the electrolyte used was LiPF6. Cell assembly was implemented in a recirculating argon glove box. Electrochemical measurements were executed by a LAHE Battery Tester under different conditions.

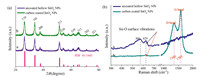

3. Results and discussionFig. 1a shows representative XRD patterns of as-prepared hollow SnO2 and SnO2@C NPs. The diffraction peaks in both curves are well indexed to the tetragonal rutile phase of SnO2 (PDF#41- 1445). The result reveals that the structure of the SnO2 is not changed by the carbon coating process. Furthermore,Raman spectroscopy was used to confirm the generation of the carbon layer on the as-prepared hollow SnO2 seeds. As shown in Fig. 1b, two peaks of 1585 cm-1 and 1360 cm-1 can be observed in the hollow SnO2@C sample,which can be attributed to E2g vibration mode of ordered C (G band) and A1g vibration mode of disordered C (D band),respectively. The peak at 560 cm-1 can be indexed to the Sn-O surface vibrations,the peak at 629 cm-1 is attributed to the A1 g mode of SnO2. The above results demonstrate that carbon has been successfully coated on the surface of SnO2 NPs,and the structure of SnO2 is not changed.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1.XRD patterns (a) and Raman spectra (b) of as-obtained hollow SnO2 and hollow SnO2@C NPs. | |

Fig. 2 shows the element valence state and the composition of the as-obtained hollow SnO2 NPs before and after carbon coating. The full-scan XPS spectra of the as-obtained hollow SnO2 and SnO2@C NPs are shown in Fig. S1 in Supporting Information. The core-level spectra of Sn 3d peaks are investigated and the results are shown in Fig. 2b. The peaks at 486.58 and 487.18 eV belong to the Sn 3d5/2,495.08 and 495.48 eV belong to Sn 3d3/2,respectively. The result illustrates the characteristics of Sn4+ in the as-prepared hollow SnO2 and SnO2@C NPs,and the result further confirms that the heat treatment did not cause the generation of metal tin. Obviously,the carbon coating reduces the peak strength of Sn 3d5/2 and 3d3/2,compared with hollow SnO2 and SnO2@C NPs. As shown in Fig. 2a,the peaks at 287.88 and 287.78 eV are assigned to C 1s. The carbon coating enhances the peak strength of C 1s,compared to the uncoated hollow SnO2 NPs. In fact,several reports show that XPS signal intensity of the core becomes weak after coating in a core-shell structure. Meanwhile,the XPS signal intensity of the shell becomes predominant [30, 31, 32]. Clearly,the above results confirm the formation of the carbon coated SnO2 core-shell NPs. The morphology and microstructure of the as-obtained hollow SnO2 NPs before and after carbon coating are investigated by TEM and HRTEM. As shown in Fig. 3a,the as-prepared samples mainly consist of uniform flower-like NPs with a mean size of ~50 nm (the histogram size distribution of SnO2 is 50.9 nm,as shown in Fig. S3a in Supporting Information). The clear contrast between the edge and the center of the particle suggests the hollow nature of NPs. The bright rings in the SAED pattern corresponds to the rutile phase of SnO2. As shown in Fig. 3b,it can be seen that as-obtained SnO2 NPs consist of clusters of SnO2 crystals and the surface of SnO2 particles are rough. There are two kinds of lattice spacings of 0.264 and 0.334 nm,which can be indexed to (1 0 1) and (0 -1 1) planes,respectively. As shown in Fig. 3c,it can be seen that the hollow SnO2@C NPs remain uniform in size and include a thin layer of carbon on the surface. As shown in Fig. 3d,the corresponding HRTEM image shows a smooth and continuous carbon layer with the thickness of about 1-2 nm (the histogram size distribution of SnO2@C is 52.2 nm,as shown in Fig. S3b). There are two kinds of lattice fringes with interplanar spacings of 0.334 and 0.264 nm, which are attributed to the (1 1 0) and (1 0 1) planes of SnO2, respectively. The above results confirm the successful coating of carbon,and the hollow nature of SnO2 NPs that is well maintained after the coating and annealing process. The thermal gravimetric results (Fig. S2 in Supporting Information) illustrate that about 17.3% of carbon has been coated on the hollow SnO2 NPs.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2.XPS core peaks of C 1s (a) and Sn 3d (b) for the as-prepared hollow SnO2 NPs before and after carbon coating. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3.TEM and HRTEM images of as-obtained hollow SnO2 (a, b, the inset scale bar is 10 nm) and SnO2@C NPs (c, d). | |

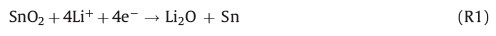

In the electrochemical measurements,the size of the electrode plate is Ø12 mm (the corresponding area is 1.1304 cm2),meanwhile, the active materials quality coating on the electrode plate is 1.5 mg. Therefore,we calculate that the mass loading is 1.327 mg cm-2 [33]. To study the electrochemical performance of the as-prepared hollow SnO2@C NPs electrodes,cyclic voltammetry (CV) analysis was performed at a scan rate of 0.5 mV s-1 and the potential range was 3.0-0.01 V (vs. Li/Li+). Fig. 4a displays the first three cycles of CV curves. A clear difference between the 1st and subsequent cycles could be observed. In the 1st cycle,a typical reduction peak occurs at ~0.7 V,suggesting the generation of solid electrolyte films and the reduction of tin oxide to metallic tin. The proposed reaction is as follows:

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4.The cyclic voltammograms curves of the hollow SnO2@C NPs (a); the charge–discharge curves of hollow SnO2@C NPs between 0.01 V and 3 V (V vs. Li/Li+) at 5 C (b), the cycle performance of hollow SnO2 NPs before and after carbon coating (c); the rate performances of hollow SnO2@C nanoparticle at variable rates (0.2–5 C, 1 C = 782 mAh g-1)(d). | |

During the negative scan,two clear peaks at 0.1 and 0.6 V could be observed,which are attributed to the generation of reversible alloy-dealloy (RAD) reaction as follows:

and the RAD reaction is mainly responsible for lithium storage capacity. In the 2nd and 3rd cycles,the CV curves are almost stable suggesting that the electrochemical performance becomes steady with reversible RAD processes. By comparison,the reduction peak at 0.7 V in the first cycle shifts to 1.01 V in the 2nd and 3rd scanning cycles,which reveals the irreversibility of the reaction during the first cycle [34] with an initial irreversible capacity loss. Another peak at 1.25 V in all the cycles correspond to the oxidation of Sn to SnO or SnO2,suggesting that the Reaction 1 (R1) is partially reversible. The electrochemistry mechanism of the as-obtained hollow SnO2@C NPs is well consistent with that of SnO2 anode materials [35].

Fig. 4b shows the 1st,2nd,100th,200th,300th and 400th cycles of charge-discharge curves of as-obtained hollow SnO2@C NPs at a current density of 3910 mA g-1 (5 C). The as-obtained SnO2@C NPs exhibit extremely high discharge capacity with the value of 1860 mAh g-1 in the 1st cycle,and the corresponding charge capacity is 1216 mAh g-1,suggesting that the initial irreversible capacity loss is about 34.6%. The decomposition of tin dioxide Reaction 1 (R1) and other possible irreversible processes result in the initial capacity loss. This phenomenon is in good agreement with SnO2-based anode materials. In the 100th,200th,300th and 400th cycles,the discharge/charge profiles show no significant degradation,which reveals that Li-insertion/extraction performance is quite stable and the discharge capacity is about 370 mA g-1. Fig. 4c shows the cycle performance of hollow SnO2 and SnO2@C NPs at the current densities of 782 mA g-1 (1 C) and 3910 mA g-1 (5 C) between 3 V and 5 mV,respectively. Clearly, hollow SnO2@C NPs demonstrate much higher capacity and better cycle stability than the hollow SnO2 NPs. For hollow SnO2@C NPs, after 573 cycles,the capacity is still up to 370 mAh g-1 at 5 C. This stable cycling is credited to the accommodating ability of SnO2 volume change during the charge-discharge process by the combining effect of nanosized SnO2,unique hollow structure and the carbon coated hollow SnO2 NPs surface. For a comparison, the hollow SnO2 NPs demonstrates a high initial-capacity but it falls off rapidly with charge/discharge cycling at 1 C. Although the bare SnO2 NPs consist of nanosized SnO2 grains and have the unique hollow structure,it cannot completely restrain the irreversible capacity loss when there is a huge volume expansion during the charge-discharge process. The cycle performance of hollow SnO2@C NPs at 1 C is shown in Fig. S3. The rate performances of as-prepared hollow SnO2@C NPs at various charge and discharge rates (from 0.2 C to 5 C) are shown in Fig. 4d. With increasing current,the discharge capacity decreased slowly. The reversible capacity is retained about 700 mAh g-1, even at high rates of 5 C. When the current returns to 0.2 C again,a high reversible capacity of ~1200 mAh g-1 is recovered. Compare with previous literature reports,the as-prepared sub-100 nm hollow SnO2@C NPs show significant enhancement in lithium storage capacity and cycle stability,because of the unique hollow structure and thin carbon layer coated on the surface of hollow SnO2 NPs,which exhibited improved cycle performance compared to the literature [36, 37, 38].

4. ConclusionIn summary,we prepared sub-100 nm hollow SnO2@C nanoparticles in a large-scale via a facile hydrothermal approach. As an anode nanomaterial for lithium ion batteries,the as-obtained hollow SnO2@C nanoparticles exhibit superior capacity and stability owing to their nanosize,unique hollow structure,and the carbon coating on the surface of hollow SnO2 nanoparticles. The thin carbon coated layer and hollow structure effectively inhibit the volume change of SnO2 during the alloy-dealloy process. The results reveal that the as-prepared sub-100 nm hollow SnO2@C nanoparticle is a promising candidate to develop high-capacity anode materials of LIBs. The present synthesis strategy could also extend to the fabrication of other electrode materials systems.

AcknowledgmentsWe greatly acknowledge partial financial support by the Program for the NSFC (Nos. 51302325,51201115,51471121), New Century Excellent Talents in University (No. NCET-12-0553), Program for Shenghua Overseas Talent (No. 1681-7607030005) from Central South University,Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2014CFB261),and the partial financial support from the Open-End Fund for the Valuable and Precision Instruments of Central South University (No. CSUZC2014032),Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2042015kf0184) and Wuhan University.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found,in the online version,at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2015.05.051.

| [1] | J.R. Dahn, T. Zheng, Y.H. Liu, J.S. Xue, Mechanisms for lithium insertion in carbonaceous materials, Science 270(1995) 590-593. |

| [2] | J.M. Tarascon, M. Armand, Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries, Nature 414(2001) 359-367. |

| [3] | X.W. Lou, J.S. Chen, P. Chen, L.A. Archer, One-pot synthesis of carbon-coated SnO2 nanocolloids with improved reversible lithium storage properties, Chem. Mater. 21(2009) 2868-2874. |

| [4] | M.G. Kim, J. Cho, Reversible and high-capacity nanostructured electrode materials for Li-ion batteries, Adv. Funct. Mater. 19(2009) 1497-1514. |

| [5] | J.X. Li, Y. Zhao, N. Wang, L.H. Guan, A high performance carrier for SnO2 nanoparticles used in lithium ion battery, Chem. Commun. 47(2011) 5238-5240. |

| [6] | J.M. Ma, J. Zhang, S.R. Wang, et al., Superior gas-sensing and lithium-storage performance SnO2 nanocrystals synthesized by hydrothermal method, CrystEng-Comm 13(2011) 6077-6081. |

| [7] | G.F. Xia, N. Li, D.Y. Li, et al., Molten-salt decomposition synthesis of SnO2 nanoparticles as anode materials for lithium ion batteries, Mater. Lett. 65(2011) 3377-3379. |

| [8] | J.J. Cai, Z.S. Li, S. Yao, et al., Close-packed SnO2 nanocrystals anchored on amorphous silica as a stable anode material for lithium-ion battery, Electrochim. Acta 74(2012) 182-188. |

| [9] | K. Ui, S. Kawamura, N. Kumagai, Fabrication of binder-free SnO2 nanoparticle electrode for lithium secondary batteries by electrophoretic deposition method, Electrochim. Acta 76(2012) 383-388. |

| [10] | W.S. Kim, Y. Hwa, J.H. Jeun, H.J. Sohn, S.H. Hong, Synthesis of SnO2 nano hollow spheres and their size effects in lithium ion battery anode application, J. Power Sources 225(2013) 108-112. |

| [11] | W. Wei, L.X. Song, L. Guo, SnO2 hollow nanospheres assembled by single layer nanocrystals as anode material for high performance Li ion batteries, Chin. Chem. Lett. 26(2015) 124-128. |

| [12] | H. Kim, J. Cho, Hard templating synthesis of mesoporous and nanowire SnO2 lithium battery anode materials, J. Mater. Chem. 18(2008) 771-775. |

| [13] | K. Shiva, S. Asokan, A.J. Bhattacharyya, Improved lithium cyclability and storage in a multi-sized pore ("differential spacers") mesoporous SnO2, Nanoscale 3(2011) 1501-1503. |

| [14] | S.J. Ding, X.W.D. Lou, SnO2 nanosheet hollow spheres with improved lithium storage capabilities, Nanoscale 3(2011) 3586-3588. |

| [15] | Z.Y. Wang, D.Y. Luan, F.Y.C. Boey, X.W. Lou, Fast formation of SnO2 nanoboxes with enhanced lithium storage capability, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133(2011) 4738-4741. |

| [16] | H.B. Wu, J.S. Chen, X.W. Lou, H.H. Hng, Synthesis of SnO2 hierarchical structures assembled from nanosheets and their lithium storage properties, J. Phys. Chem. C 115(2011) 24605-24610. |

| [17] | C. Wang, Y. Zhou, M. Ge, et al., Large-scale synthesis of SnO2 nanosheets with high lithium storage capacity, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132(2009) 46-47. |

| [18] | P. Wu, M.Y. Du, H. Zhang, C.X. Zhai, D.R. Yang, Self-templating synthesis of SnO2-carbon hybrid hollow spheres for superior reversible lithium ion storage, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 3(2011) 1946-1952. |

| [19] | X.W. Lou, Y. Wang, C. Yuan, J.Y. Lee, L.A. Archer, Template-free synthesis of SnO2 hollow nanostructures with high lithium storage capacity, Adv. Mater. 18(2006) 2325-2329. |

| [20] | X.W. Lou, D. Deng, J.Y. Lee, L.A. Archer, Preparation of SnO2/carbon composite hollow spheres and their lithium storage properties, Chem. Mater. 20(2008) 6562-6566. |

| [21] | W.M. Zhang, X.L. Wu, J.S. Hu, Y.G. Guo, L.J. Wan, Carbon coated Fe3O4 nanospindles as a superior anode material for lithium-ion batteries, Adv. Funct. Mater. 18(2008) 3941-3946. |

| [22] | H. Li, H. Zhou, Enhancing the performances of Li-ion batteries by carbon-coating:present and future, Chem. Commun. 48(2012) 1201-1217. |

| [23] | J. Liu, W. Li, A. Manthiram, Dense core-shell structured SnO2/C composites as high performance anodes for lithium ion batteries, Chem. Commun. 46(2010) 1437-1439. |

| [24] | Y. Chen, Q.Z. Huang, J. Wang, Q. Wang, J.M. Xue, Synthesis of monodispersed SnO2@C composite hollow spheres for lithium ion battery anode applications, J. Mater. Chem. 21(2011) 17448-17453. |

| [25] | S.M. Paek, E. Yoo, I. Honma, Enhanced cyclic performance and lithium storage capacity of SnO2/graphene nanoporous electrodes with three-dimensionally delaminated flexible structure, Nano Lett. 9(2008) 72-75. |

| [26] | L. Wang, D. Wang, H.Z. Dong, F.X. Zhang, J. Jin, Interface chemistry engineering for stable cycling of reduced GO/SnO2 nanocomposites for lithium ion battery, Nano Lett. 13(2013) 1711-1716. |

| [27] | H. Park, T. Song, H. Han, et al., SnO2 encapsulated TiO2 hollow nanofibers as anode material for lithium ion batteries, Electrochem. Commun. 22(2012) 81-84. |

| [28] | N. Feng, L. Qiao, D.K. Hu, X.L. Sun, P. Wang, D.Y. He, Synthesis, characterization, and lithium-storage of ZnO-SnO2 hierarchical architectures, RSC Adv. 3(2013) 7758-7764. |

| [29] | W. Wu, S.F. Zhang, J. Zhou, et al., Controlled synthesis of monodisperse sub-100 nm hollow SnO2 nanospheres:a template- and surfactant-free solutionphase route, the growth mechanism, optical properties, and application as a photocatalyst, Chem. Eur. J. 17(2011) 9708-9719. |

| [30] | S.Y. Liu, Y.H. Ma, S.P. Armes, C. Perruchot, J.F. Watts, Direct verification of the core-shell structure of shell cross-linked micelles in the solid state using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, Langmuir 18(2002) 7780-7784. |

| [31] | Q.Y. Tian, W. Wu, L.L. Sun, et al., Tube-like ternary α-Fe2O3@SnO2@Cu2O sandwich heterostructures:synthesis and enhanced photocatalytic properties, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6(2014) 13088-13097. |

| [32] | W. Wu, Q.G. He, H. Chen, J.X. Tang, L.B. Nie, Sonochemical synthesis, structure and magnetic properties of air-stable Fe3O4/Au nanoparticles, Nanotechnology 18(2007) 145609. |

| [33] | J.J. Chen, K. Yano, Highly monodispersed tin oxide/mesoporous starbust carbon composite as high-performance Li-ion battery anode, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5(2013) 7682-7687. |

| [34] | X.F. Li, X.B. Meng, J. Liu, et al., Tin oxide with controlled morphology and crystallinity by atomic layer deposition onto graphene nanosheets for enhanced lithium storage, Adv. Funct. Mater. 22(2012) 1647-1654. |

| [35] | J.P. Liu, Y.Y. Li, X.T. Huang, et al., Direct growth of SnO2 nanorod array electrodes for lithium-ion batteries, J. Mater. Chem. 19(2009) 1859-1864. |

| [36] | X.W. Guo, X.P. Fang, Y. Sun, et al., Lithium storage in carbon-coated SnO2 by conversion reaction, J. Power Sources 226(2013) 75-81. |

| [37] | M. He, L.X. Yuan, X.L. Hu, et al., A SnO2@carbon nanocluster anode material with superior cyclability and rate capability for lithium-ion batteries, Nanoscale 5(2013) 3298-3305. |

| [38] | M. Zhang, Y.W. Li, E. Uchaker, et al., Homogenous incorporation of SnO2 nanoparticles in carbon cryogels via the thermal decomposition of stannous sulfate and their enhanced lithium-ion intercalation properties, Nano Energy 2(2013) 769-778. |

2015, Vol.26

2015, Vol.26