b School of Medical Engineering Hefei University of Technology, Hefei 230009, China

The conversion of biomass to chemicals has become an important research area in the field of biomass utilization in recent years [1]. Of particular importance is the transformation of biomass to 5-hydroxylmethylfurfural (5-HMF,1) [2],which can be obtained easily from cellulose [3] and transformed readily to fuels and other value-added chemicals [4]. As one of the most important derivatives of 1,2,5-diformylfuran (2,5-DFF,2) has attracted much attention because of its applications in the synthesis of a number of valuable compounds such as pharmaceutical intermediates, fungicides,heterocyclic ligands and others [5, 6, 7, 8]. Early precedents for the oxidation of 1-2,however,suffer from drawbacks such as the use of stoichiometric amount of relatively expensive oxidant (NaOCl,pyridinium chlorochromate etc.) and the over-oxidation of 2 to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (2,5-FDCA) [9]. Consequently,the use of O2,or preferably air,as the oxidant has been studied intensively. Carlini et al. and Corma et al. reported the oxidation of 1-2 in air at high temperatures with vanadium-based heterogeneous catalysts (Scheme 1a and b) [10]. Xu et al. developed a bimetallic CuNO3/VOSO4 catalytic system that allows room temperature (RT) oxidation,albeit under O2 [11]. Very recently, Riisager et al. discovered that such oxidation reactions can also be achieved efficiently in air at 50 ℃ using CuCl/TEMPO/Bipy as the catalyst (Scheme 1d) [12]. In 2012,our group reported an environmentally benign catalyst K-OMS-2 for the oxidation of 1-2 in O2 at 110 ℃ with excellent yield and selectivity (Scheme 1e) [13]. Other catalytic systems,such as Ru,Co,Mn and others [14, 15, 16, 17],have also been developed for oxidation. Yet,the development of efficient catalysts for the oxidation of 1-2 in air remains an important challenge.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme. 1.The processes for the oxidation of 5-HMF to 2,5-DFF. | |

All reagents were used as received from commercial sources unless specified otherwise,or prepared as described in the literature. 1H NMR,13C NMR,spectra were recorded on a Bruker advance 400 spectrometer at ambient temperature in CDCl3 unless otherwise noted. Data for 1H NMR are reported as follows: chemical shift (δ ppm),multiplicity,integration,and coupling constant (Hz). Data for 13C NMR are reported in chemical shifts (δ ppm). Gas chromatographic (GC) analyses were performed on a Shimadzu GC-2014 series GC system equipped with a flameionization detector using biphenyl as an internal standard. The temperature was 150 ℃. Organic solutions were concentrated under reduced pressure on a Buchi rotary evaporator. Flash column chromatographic purification of products was accomplished using forced-flow chromatography on Silica Gel (200-300 mesh).

2.2. The typical process for aerobic oxidation of 5-HMF to 2,5-DFF5-HMF (63mg,0.5mmol),Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (10.1 mg,0.025 mmol, 5mol%),TEMPO (7.8 mg,0.025mmol,5 mol%),NaCl (1.5 mg, 0.025mol,5 mol%) were charged into a tube,and then 2 mL of DCE was added. The reactionmixture was stirred at roomtemperature for 4 h in open air. Then,the reactionwas monitored byGC analysis using 5-methyl-2-furaldehyde as an internal standard.

Separation of 2,5-DFF from reaction solution: after the epinephelos solution was filtered and washed with ethyl acetate for three times,the organic solvents were evaporated and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (PE:EA = 3:1) to give the desired product in 88% yield (detected by 1H NMR). 1H NMR (400 MHz,CDCl3): δ 9.84 (s,2H),7.33 (s,2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz,CDCl3): δ 179.34,154.30,119.43.

2.3. The synthesis of 2,5-FDCA2,5-DFF (62 mg,0.5 mmol) were charged into a tube,and 0.5 mL of tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP,70% in water) (7 equiv.) was added. The tube was stirred at 110 ℃ for 6 h. The liquid was evaporated under reduced pressure,and then washed by ethyl acetate for 3 times,the remaining solid was dried in high vacuum to afford 90% yield of 2,5-FDCA (detected by 1H NMR). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6,400 MHz): δ 7.29 (s,2H),13.67 (br. s,2H) .13C NMR (DMSO-d6,100 MHz): δ 118.84,147.52,159.40.

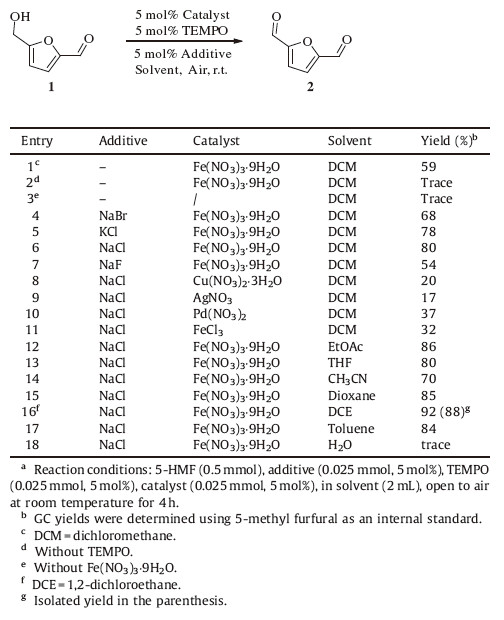

3. Results and discussionOur results indicate that Fe(NO3)3·9H2O/TEMPO can catalyze the oxidation of 1-2 in air at room temperature. The initial test was performed in dichloromethane (DCM),giving a 59% yield and a 99% selectivity (Table 1,entry 1). Control experiments revealed that the reaction shut down completely without the addition of Fe(NO3)3·9H2O or TEMPO (Table 1,entries 2 and 3). Next,we examined a number of halide salts for the oxidation process. It was found that the use of NaBr,KCl and NaCl can improve significantly the yield of 2 from 59% to 68%,78% and 80%,respectively (Table 1, entries 4-6). NaF is the only exception,which slightly decreased the yield of 2 to 54% (Table 1,entry 7). Halide anions have been shown to act as ligands for transition metals [19]. The Cl- from NaCl may act as a special electron-donating ligand to provide electrons to the d orbitals of Fe3+ to accelerate the semi-oxidative addition-type coupling with TEMPO (A proposed mechanism was shown in the Supporting information) [18]. Other metal catalysts such as Cu(NO3)2·3H2O,AgNO3,Pd(NO3)2 and FeCl3 could also initiate the reaction,albeit giving lower yields of 2 (Table 1,entries 8-11). In general,the reaction yield can be further improved by using other organic solvents (Table 1,entries 12-17). However, when the reaction was conducted in water,only a trace amount of 2 could be obtained (Table 1,entry 18). The use of 1,2- dichloroethane (DCE) as the solvent gave the best result (GC yield, 92%; isolated yield,88%) (Table 1,entry 16).

| Table 1 Fe/TEMPO catalyzed oxidation of 5-HMF to 2,5-DFF in air at room temperaturea. |

Remarkably,the optimized protocol is also efficient for a multigram-scale synthesis of 2. As shown in Scheme 2,10 g of 1 with 5 mol% Fe(NO3)3·9H2O,TEMPO,and NaCl in DCE at room temperature using air as the oxidant afforded 7.8 g of 2 in 10 h (recrystallized yield,78%).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme. 2.Gram-scale synthesis of 2,5-DFF. | |

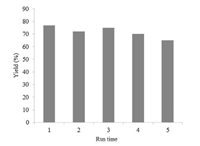

The recyclability of the catalyst further demonstrates the great potential of this new protocol in practical applications (Fig. 1). A simple distillation of a crude reaction product mixture led to an efficient recovery of the active catalyst. A 65% yield of 2 (recrystallized yield) was achieved even after recycling the catalyst for 4 times.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1.The reusability of the catalyst system. | |

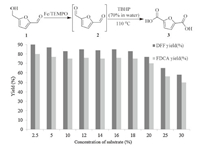

Finally,we developed a two-step process for the synthesis of 2,5-FDCA (3),an important derivative of 5-HMF [1a, 4b],based on the new iron-catalyzed protocol. This process involves (1) the selective oxidation of 1-2,(2) a simple oxidation of 2-3 by tertbutyl hydroperoxide (TBHP). Compound 3 has been identified as one of the twelve platform chemicals [20],which is useful for the synthesis of bio-degradable polymers [21, 4a]. The direct synthesis of 3 from 1 has been achieved using stoichiometric oxidants (KMnO4) or homogeneous catalysts (Co/MnBr) [15b]. Recently,a number of heterogeneous catalytic systems for the synthesis of 3 have also been developed. However,these reported protocols only work at low substrate concentrations (typically < 2 wt%) [22], limiting their practical applications. With our new process, moderate to good yields of 3 were achieved at significantly higher substrate concentrations (Scheme 3). For instance,an 80% yield of 3 was obtained when the substrate concentration of 1 was 2.5%. Even with a much higher concentration of 1 (18%),a 75% yield of 3 was obtained.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme. 3.One-pot synthesis of 2,5-FDCA from HMF via 2,5-DFF. | |

In conclusion,we identified an inexpensive,efficient,and selective iron catalyst for the oxidation of 5-HMF to 2,5-DFF in air at room temperature. The catalyst showed excellent recyclability for multigram-scale syntheses. Furthermore,a two-step process was developed successfully for the oxidation of 5-HMF to 2,5-FDCA at remarkably high substrate concentrations. Further studies to improve the catalytic system for the conversion of biomass to chemicals are currently undergoing.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors are grateful to the National Basic Research Program of China (Nos. 2013CB228103,2012CB215306),NNSFC (Nos. 21472033,21325208,21172209),FRFCU (No. WK2060190025), SRFDP (No. 20123402130008),CAS (No. KJCX2-EW-J02) and Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation for the financial support.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found,in the online version,at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2015.07. 001.

| [1] | (a) A. Corma, S. Iborra, A. Velty, Chemical routes for the transformation of biomass into chemicals, Chem. Rev. 107(2007) 2411-2502;(b) J.N. Chheda, G.W. Huber, J.A. Dumesic, Liquid-phase catalytic processing of biomass-derived oxygenated hydrocarbons to fuels and chemicals, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46(2007) 7164-7183;(c) P. Gallezot, Conversion of biomass to selected chemical products, Chem. Soc. Rev. 41(2012) 1538-1558;(d) D.M. Alonso, S.G. Wettstein, J.A. Dumesic, Bimetallic catalysts for upgrading of biomass to fuels and chemicals, Chem. Soc. Rev. 41(2012) 8075-8098;(e) M. Besson, P. Gallezot, C. Pinel, Conversion of biomass into chemicals over metal catalysts, Chem. Rev. 114(2014) 1827-1870. |

| [2] | (a) Y. Roman-Leshkov, J.N. Chheda, J.A. Dumesic, Phase modifiers promote efficient production of hydroxymethylfurfural from fructose, Science 312(2006) 1933-1937;(b) H.B. Zhao, J.E. Holladay, H. Brown, et al.,Metal chlorides in ionic liquid solvents convert sugars to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, Science 316(2007) 1597-1600;(c) G. Yong, Y.G. Zhang, J.Y. Ying, Efficient catalytic systemfor the selective production of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from glucose and fructose, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47(2008) 9345-9348;(d) S.Q. Hu, Z.F. Zhang, B.X. Han, Efficient conversion of glucose into 5-hydroxymethylfurfural catalyzed by a common lewis acid SnCl4 in an ionic liquid, Green Chem. 11(2009) 1746-1749;(e) M. Mascal, E.B. Nikitin, High-yield conversion of plant biomass into the key value-added feedstocks 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural, levulinic acid, and levulinic esters via 5-(chloromethyl)furfural, Green Chem. 12(2010) 370-373;(f) T. Stahlberg, S.R. Rodriguez, A. Riisager, Metal-free dehydration of glucose to 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural in ionic liquidswith boric acid as a promoter, Chem. Eur. J. 17(2011) 1456-1464;(g) F. Liu, J. Barrault, K. Vigier, F. Jerome, Dehydration of highly concentrated solutions of fructose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in a cheap and sustainable choline chloride/carbon dioxide system, ChemSusChem 5(2012) 1223-1226;(h) F.R. Tao, C. Zhuang, Y.Z. Cui, et al., Dehydration of glucose into 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in SO3H-functionalized ionic liquids, Chin. Chem. Lett. 25(2014) 757-761. |

| [3] | (a) J.B. Binder, R.T. Raines, Simple chemical transformation of lignocellulosic biomass into furans for fuels and chemicals, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131(2009) 1979-1985;(b) W.H. Peng, Y.Y. Lee, C. Wu, et al., Acid-base bi-functionalized, large-pored mesoporous silica nanoparticlesfor cooperative catalysis of one-pot cellulose-to-HMF conversion, J. Mater. Chem. 22(2012) 23181-23185. |

| [4] | (a) C. Moreau, M.N. Belgacem, A. Gandini, Recent catalytic advances in the chemistry of substituted furans from carbohydrates and in the ensuing polymers, Top. Catal. 27(2004) 11-30;(b) R.J. Putten, J.C. Waal, E. Jong, et al., Hydroxymethylfurfural, a versatile platform chemical made from renewable resources, Chem. Rev. 113(2013) 1499-1597. |

| [5] | K.T. Hopkins, W.D. Wilson, B.C. Bendan, et al., Extended aromatic furan amidino derivatives as anti-pneumocystis carinii agents, J. Med. Chem. 41(1998) 3872-3878. |

| [6] | M. Del Poeta, W.A. Schell, C.C. Dykstra, et al., Structure-in vitro activity relationships of pentamidine analogues and dication-substituted bis-benzimidazoles as new antifungal agent, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42(1998) 2495-2502. |

| [7] | D.T. Richter, T.D. Lash, Oxidation with dilute aqueous ferric chloride solutions greatly improves yields in the 4+1 synthesis of sapphyrins, Tetrahedron Lett. 40(1999) 6735-6738. |

| [8] | (a) O.W. Howarth, G.G. Morgan, V. McKee, et al., Conformational choice in disilver cryptates; a 1H NMR and structural study, J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 12(1999) 2097-2102;(b) Z. Hui, A. Gandini, Polymeric schiff bases bearing furan moieties, Eur. Polym. J. 28(1992) 1461-1469;(c) M. Baumgarten, N. Tyutyulkov, Nonclassical conducting polymers:new approaches to organic metals, Chem. Eur. J. 4(1998) 987-989;(d) A.S. Amarasekara, D. Green, L.D. Williams, Renewable resources based polymers:synthesis and characterization of 2,5-diformylfuran-urea resin, Eur. Polym. J. 45(2009) 595-598. |

| [9] | (a) W. Partenheimer, V.V. Grushin, Synthesis of 2,5-diformylfuran and furan-2,5-dicarboxylic acid by catalytic air-oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Unexpectedly selective aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde with metal/bromide catalysts, Adv. Synth. Catal. 343(2001) 102-111;(b) M. Krçger, K.D. Vorlop, A new approach for the production of 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid by in situ oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural starting from fructose, Top. Catal. 13(2000) 237-242. |

| [10] | (a) C. Carlini, P. Patrono, A.M.R. Galletti, et al., Selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde to furan-2,5-dicarboxaldehyde by catalytic systems based on vanadyl phosphate, Appl. Catal. A:Gen. 289(2005) 197-204;(b) O.C. Navarro, A.C. Canos, S.I. Chornet, Chemicals from biomass:aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde into diformylfurane catalyzed by immobilized vanadyl-pyridine complexes on polymeric and organofunctionalized mesoporous support, Top. Catal. 52(2009) 304-314. |

| [11] | J.P. Ma, Z.T. Du, J. Xu, et al., Efficient aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran, and synthesis of a fluorescent material, ChemSusChem 4(2011) 51-54. |

| [12] | T.S. Hansen, I. Sádaba, A. Riisager, Cu catalyzed oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran and 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid under benign reaction conditions, Appl. Catal. A:Gen. 456(2013) 44-50. |

| [13] | Z.Z. Yang, J. Deng, T. Pan, et al., A one-pot approach for conversion of fructose to 2,5-diformylfuran by combination of Fe3O4-SBA-SO3H and K-OMS-2, Green Chem. 14(2012) 2986-2989. |

| [14] | (a) J.F. Nie, J.H. Xie, H.C. Liu, J. Catal, Efficient aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran on supported Ru catalysts 301(2013) 83-91;(b) A. Takagaki, M. Takahashi, S. Nishimura, et al., One-pot synthesis of 2,5-diformylfuran from carbohydrate derivatives by sulfonated resin and hydrotalcite-supported ruthenium catalysts, ACS Catal. 1(2011) 1562-1565. |

| [15] | B. Saha, S. Dutta, M.M. Abu-Omar, Aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxylmethylfurfural with homogeneous and nanoparticulate catalysts, Catal. Sci. Technol. 2(2012) 79-81. |

| [16] | A.S. Amarasekara, D. Green, E. McMillan, Efficient oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran using Mn(III)-salen catalysts, Catal. Commun. 9(2008) 286-288. |

| [17] | (a) N.T. Le, P. Lakshmanan, K. Cho, et al., Selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural into 2,5-diformylfuran over VO2+ and Cu2+ ions immobilized on sulfonated carbon catalysts, Appl. Catal. A:Gen. 464(2013) 305-312;(b) I. Sádaba, Y.Y. Gorbanev, A. Riisager, Catalytic performance of zeolite-supported vanadia in the aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran, ChemCatChem 5(2013) 284-293. |

| [18] | S.M. Ma, J.X. Liu, S.H. Li, et al., Development of a general and practical iron nitrate/TEMPO-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of alcohols to aldehydes/ketones:catalysis with table salt, Adv. Synth. Catal. 353(2011) 1005-1017. |

| [19] | E.W. Abel, F.G.A. Stone, G. Wilkinson, Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry II, vol. 7, Pergamon, 1995, pp. 78-79. |

| [20] | T. Werby, G. Petersen, Top Value-Added Chemicals from Biomass, vol. 1, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, 2004p. 27. |

| [21] | (a) J.P. Ma, Y. Pang, M. Wang, et al., The copolymerization reactivity of diols with 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid for furan-based copolyester materials, J. Mater. Chem. 22(2012) 3457-3461;(b) J.P. Ma, X.F. Yu, J. Xu, Y. Pang, Synthesis and crystallinity of poly (butylene 2, 5-furandicarboxylate), Polymer 53(2012) 4145-4151. |

| [22] | (a) E. Taarning, I.S. Nielsen, K. Egeblad, et al., Chemicals from renewables:aerobic oxidation of furfural and hydroxymethylfurfural over gold catalysts, Chem-SusChem 1(2008) 75-78;(b) O. Casanova, S. Iborra, A. Corma, Biomass into chemicals:aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid with gold nanoparticle catalysts, ChemSusChem 2(2009) 1138-1144;(c) M.A. Lilga, R.T. Hallen, M. Gray, Production of oxidized derivatives of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), Top. Catal. 53(2010) 1264-1269;(d) S.E. Davis, L.R. Houk, E.C. Tamargo, et al., Oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural over supported Pt, Pd and Au catalysts, Catal. Today 160(2011) 55-60;(e) S.E. Davis, B.N. Zope, R.J. Davis, On the mechanism of selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid over supported Pt and Au catalysts, Green Chem. 14(2012) 143-147;(f) J.M. Gallo, D.M. Alonso, J.A. Dumesic, Production and upgrading of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural using heterogeneous catalysts and biomass-derived solvents, Green Chem. 15(2013) 85-90;(g) J. Cai, H. Ma, Q. Song, Gold nanoclusters confined in a supercage of Y zeolite for aerobic oxidation of HMF under mild conditions, Chem. Eur. J. 19(2013) 14215-14223;(h) G.S. Yi, S.P. Teong, Y.G. Zhang, Purification of biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and its catalytic conversion to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid, Chem-SusChem 7(2014) 2131-2137; (i) S. Siankevich, G. Savoglidis, P.J. Dyson, A novel platinum nanocatalyst for the oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-Furandicarboxylic acid under mild conditions, J. Catal. 315(2014) 67-74. |

2015, Vol.26

2015, Vol.26