In recent years, increasing interest has been focused on the rational design and construction of metal-organic crystalline materials, not only due to their fascinating structures and topologies, but also their potential applications, such as photoluminescence, adsorption/separation, and magnetic materials [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. It is well known that the properties of the resultant complexes are mainly determined by their structural characteristics. However, there are many factors that impact the final product structures, such as the coordination behavior of the ligand [14, 15, 16], coordination geometries of the metal ions [17, 18], the presence of an auxiliary ligand [19, 20, 21], reaction temperature [22- 24], and so on [25, 26, 27]. Therefore, it is still a great challenge to undertake and realize the prediction and targeted construction of coordination architectures [28, 29]. Carboxylates, especially for benzene-based di- or multi-carboxylic acids, as a time-honored class of versatile organic linkers with various coordination modes, have been widely used in the construction of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) which exhibit specific or multifunctional properties [30, 31]. In addition, the skillful introduction of pyridineanalogs as auxiliary ligands into the reaction systems involving various carboxylic acid ligands may generate intriguing coordination architectures [32, 33, 34]. As a continuation of our efforts to investigate the coordination chemistry of tetrazol-carboxylate ligands [9], we chose 5-(1H-tetrazol-1-yl)isophthalic acid (H2L) as the primary ligand considering its bi-functional coordination abilities and pyridine-analogs (2, 2'-bipyridine, 4, 4'-bipyridine and 1, 3-di(4-pyridyl)propane) as auxiliary ligands to construct carboxylate/ pyridine-Zn(II) coordination architectures for the following purposes: (1) there are only a few reports of MOFs that are constructed via tetrazole functionalized aromatic carboxylic acids [9, 35]. (2) The ligand comprised multiple coordinated groups which is suitable for building extended and highly connected frameworks. (3) Tetrazolyl tends to participate in the forming of weak intermolecular forces (such as hydrogen bond, p-p stacking interactions, etc.), which may stabilize certain structures and guide the self-assembly of the supramolecular framework. Herein, we report the syntheses, crystal structures, and luminescent properties of three Zn(II) complexes: {[Zn(L)(2, 2'-bpy)(DMF)](DMF)}n (1); {[Zn(L)(4, 4'-bpy)](DMF)0.5(CH3OH)(H2O)}n (2); {[Zn(L)(dpp)] (H2O)2}n (3) where 2, 2'-bpy = 2, 2'-bipyridine; 4, 4'-bpy = 4, 4'- bipyridine; and dpp = 1, 3-di(4-pyridyl)propane. The influences of the nature of the ligand, the auxiliary ligand, and weak interactions on the formation of such coordination architectures are discussed in detail.

2. ExperimentalAll the solvents and reagents for synthesis were obtained commercially and used as received. The ligand 5-(1H-tetrazol-1- yl)isophthalic acid was synthesized by a similar method according to the literature [36]. Infrared (IR) spectra were measured on a TENSOR 27 OPUS (Bruker) Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectrometer using KBr disks dispersed with sample powders in the 4000-400 cm-1 range. Elemental analyses (C, H, and N) were performed on a Perkin-Elmer 240C Analyzer. The X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) was recorded on a Rigaku D/Max-2500 Diffractometer at 40 kV, 100 mA for a Cu-target tube and a graphite monochromator. Simulation of the XRPD spectra was carried out by the single-crystal data and diffraction-crystal module of the mercury (Hg) program available free of charge via the Internet at http://www.iucr.org. Thermogravimetric (TG) analyses were carried out on a standard Rigaku TG-DTA Analyzer with a heating rate of 10 °C min-1 from ambient temperature to 600 °C; an empty Al2O3 crucible was used as reference. Solid-state luminescence spectra were recorded at room temperature on a Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrometer (Varian, USA).

Synthesis of {[Zn(L) (2, 2'-bpy)(DMF)](DMF)}n (1): A mixture of H2L (47 mg, 0.2 mmol), 2, 2'-bpy (31 mg, 0.2 mmol) and Zn(NO3)2•6H2O (59 mg, 0.2 mmol) in DMF/MeOH (2:1 v/v) solution (15 ml) was stirred at 60 °C for 10 min, then filtered. The filtrate was kept in a beaker at room temperature. Colorless block-shaped crystals suitable for single crystal X-ray crystallographic analysis were obtained after one month, washed with DMF and dried in air. Yield: ~30% (based on H2L). Anal. Calcd. (%) for C25H26N8O6Zn (MW = 599.91): C, 50.05; H, 4.37; N, 18.68. Found (%): C, 50.49; H, 4.52; N, 18.92. IR (KBr pellet, cm-1): 3443 (br), 3150 (m), 1657 (vs), 1475 (m), 1388 (vs), 1317 (m), 1252 (w), 1221 (w), 1179 (w), 1158 (w), 1110 (m), 1062 (w), 1018 (m), 968 (w), 911 (w), 867 (w), 782 (s), 765 (s), 731 (m), 664 (w), 413 (w).

Synthesis of {[Zn(L)(4, 4'-bpy)](DMF)0.5(CH3OH)(H2O)}n (2): Using 4, 4'-bpy instead of 2, 2'-bpy, colorless block-shaped crystals of 2 were obtained by the similar method described for 1 in one week. Yield: ~40% (based on H2L). Anal. Calcd. (%) for C21.5H21.5N6.5O6.5 Zn (MW = 540.32): C, 47.79; H, 4.01; N, 16.85. Found (%): C, 48.07; H, 3.82; N, 17.12. IR (KBr pellet, cm-1): 3466 (br), 3115 (w), 1681 (m), 1627 (s), 1477 (w), 1392 (vs), 1220 (m), 1092 (m), 1073 (m), 1048 (m), 1012 (m), 958 (w), 935 (w), 857 (w), 813 (m), 783 (s), 751 (m), 726 (s), 633 (m), 572 (w), 494 (w), 451 (w).

Synthesis of {[Zn(L)(dpp)](H2O)2}n (3): Straw yellow blockshaped crystals of 3 suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained by the similar method described for 1, except that dpp was used instead of 2, 2'-bpy. Yield: ~40% (based on H2L). Anal. Calcd. (%) for C22H22N6O6Zn (MW = 531.83): C, 49.69; H, 4.17; N, 15.80. Found (%): C, 49.97; H, 4.52; N, 16.02. IR (KBr pellet, cm-1): 3442 (br), 3150 (m), 2952 (m), 1620 (s), 1585 (s), 1469 (m), 1433 (s), 1366 (vs), 1221 (m), 1147 (w), 1096 (m), 1072 (m), 1031 (m), 968 (w), 924 (w), 856 (w), 822 (m), 781 (s), 716 (m), 619 (m), 518 (w).

Crystallographic studies: Single crystal X-ray diffraction measurements for complexes 1-3 were carried out on a Bruker Smart 1000 CCD Diffractometer equipped with a graphite crystal monochromator situated in the incident beam for data collection at 293 K. The determinations of unit cell parameters and data collections were performed with Mo Ka radiation (l = 0.71073Å ) by v scan mode and unit cell dimensions were obtained with least-squares refinements. The program, SAINT [37], was used for integration of the diffraction profiles. Semi-empirical absorption corrections were applied using the multi-scan program, SADABS. All structures were solved by direct methods using the SHELXS program of the SHELXTL package and refined by fullmatrix least-squares methods with the technique using SHELXTL (semi-empirical absorption corrections were applied using SADABS program) [38]. The Zn atoms were found from E-maps and other non-hydrogen atoms were located in successive difference Fourier syntheses. The final refinement was performed by full-matrix, least-squares methods with anisotropic thermal parameters for non-hydrogen atoms on F2. The hydrogen atoms of the ligands were generated theoretically onto the specific atoms and refined isotropically with fixed thermal factors. The hydrogen atoms of the dissociative water molecules and DMF molecules in 2 were not added. Details of the X-ray crystal structure analysis of 1- 3 are summarized in Table S1 in Supporting information, and the relevant bond length and bond angles are summarized in Table S2 in Supporting information.

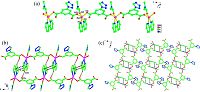

3. Results and discussionThe phase purity of 1-3 was confirmed by XRPD (Fig. S1 in Supporting information) The X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) patterns of solid 1-3 are coincident with the simulated patterns derived from the X-ray single crystal data, implying that the bulk sample is the same as the single crystal. Single crystal X-ray analysis reveals 1 has a two-dimensional (2D) supramolecular framework based on one-dimensional (1D) coordination chains with the 2, 2'-bpy as auxiliary ligand. The asymmetric unit of 1 consists of one Zn(II) ion, one L2- ligand, one 2, 2'-bpy ligand, one coordinated DMF molecule and one dissociative DMF molecule. The Zn(II) central ion is five-coordinated by two oxygen atoms from two L2- ligands, two nitrogen atoms from one 2, 2'-bpy ligand and one oxygen atom from one DMF molecule, in a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry with bond angles around Zn(II) ranging from 76.49(19) to 167.88(17)°. The bond lengths of Zn-O range from 2.012(4) to 2.134(4)Å and Zn-N are 2.173(5)Å and 2.094(4)Å , respectively. Each L2- ligand links two Zn(II) ions forming the 1D chain along b axis (Fig. 1a), while the coordinated 2, 2'-bpy and DMF molecules are located at both sides of such 1D chain, respectively. It is noteworthy that the adjacent chains are connected to the 1D double-chain via H-bonds between the oxygen atoms of L2- ligands and 2, 2'-bpy molecules, and there are p-p interactions between the 2, 2'-bpy rings in the double-chain (the center-to-center distance is 3.662Å , the dihedral angel is 0.028) (Fig. 1b), which also stabilized such supramolecular structure. Moreover, these double-chains are further connected into the 2D supramolecular network by the π-π interactions between the tetrazole rings of L2- ligands with a 3.665Å center-tocenter distance and dihedral angel being 0.028 (Fig. 1c). Details of the H-bonds data in 1 are summarized in Table S3 in Supporting information.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1.(a) The coordination environment of Zn(II) center and the 1D chain structure of 1 (symmetry code: A x, y + 1, z; B x, y-1, z); (b) the 1D double chain supramolecular structure connected by H-bonds and π-π stacking interactions between the 2, 2'-bpy rings; and (c) the 2D double layer supramolecular framework formed by the π-π stacking interactions between the tetrazole rings. | |

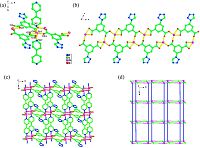

When 4, 4'-bipy was used instead of 2, 2'-bpy, complex 2 with an unexpected 2D double layer network structure was obtained. The asymmetric unit of 2 consists of one Zn(II) ion, one L2- ligand, one 4, 4'-bpy ligand, half dissociative DMF molecule, one dissociative methanol molecule and one dissociative water molecule. The Zn(II) central ion, located at inversion centers with a distorted octahedral coordination environment, in which the equatorial plane is made up of four carboxylate oxygen atoms from three L2- ligands and the axial sites are occupied by two N atoms from two 4, 4'-bpy with the Zn-N bond length being 2.167(4)Å and 2.179(4)Å , respectively (Fig. 2a). The bond lengths of Zn-O range from 2.040(3) to 2.370(4)Å and the bond angles of O-Zn-O range from 59.14(13)˚ to 158.48(13)˚ , O-Zn-N range from 86.02(14)˚ to 95.17(14)˚ , N-Zn-N being of 176.76(14)˚ , which indicates that the distortion of such octahedral configuration root in the coordination equatorial plane. It is interesting that the two carboxylate groups in one L2- ligand present distinct coordination modes in 2: One is a bidentate chelating mode, chelating one Zn(II) ion; while the other adopts bidentate bridging mode, linking two Zn(II) ions. Thus, each L2- ligand links three Zn(II) ions to result in the 1D Zn-carboxylate double-chain along a axis, in which two adjacent Zn(II) ions (Zn• • •Zn distance is 4.347Å ) are coordinated by two carboxylates with bridging mode from two different L2- ligands and two carboxylates by chelating mode from the other two L2- ligands forming the [Zn2(OOCR)4] structural unit (Fig. 2b). Moreover, the adjacent Zn-carboxylate double-chains are further connected by the assistant ligands 4, 4'-bipy to give rise to a 2D network along the b axis (Fig. 2c). In addition, there are weak interactions of C-H• • •O and O-H• • •O between the dissociative solvent molecules and the coordination layer (Table S3 in Supporting information), which further stabilizes the 2D coordination network of 2.

For better understanding of the structure of 2, topology analysis was performed. By considering the Zn1 ions as 5-connected nodes and the carboxylate ligands as 3-connected nodes, the two dimensional structure could be simplified as a 3, 5-connected network with point symbol (42.6) (42.67.8). It should be noted that though 3, 5-connected topology is rarely reported in three-dimensional networks, and no 3, 5-connected 2D network has been recorded in the Reticular Chemistry Structure Resource (RCSR) database [39]. Therefore complex 2 could be considered as a unique sample of 3, 5-connected 2D topology network (Fig. 2d).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2.(a) The coordination environment of Zn(II) center (symmetry codes: A-x, -y + 1,-z + 1;B-x + 1, -y + 1, -z + 1;Cx, y + 1, z); (b) the 1D Zn(II)-carboxylate double chain along a axis in 2; (c) projection view of the 2D double layer framework of 2 along the ab plane; (d) schematic illustrating the (42.6) (42.67.8) topology of the 2D network of 2 (ligand L2- is shown as green ball and Zn(II) ion as pink ball). | |

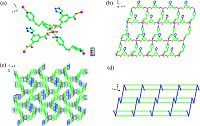

To further investigate the flexibility of auxiliary ligands on the construction of such Zn-carboxylate systems, dpp ligand was used instead of 4, 4'-bpy to perform the reaction with H2L and Zn(NO3)2•6H2O. Single crystal X-ray diffraction reveals that complex 3 crystallizes in a monoclinic space group P21/c and has an infinite 3D supramolecular structure based on 2D layers possessing a wrinkled (4, 4) grid structure. The asymmetric unit of 3 contains one Zn(II) ion, one L2- ligand, one dpp ligand and two uncoordinated water molecules. Different from that of 2, the central Zn(II) ion is four-coordinated by two oxygen atoms from two L2- ligands and two N atoms from two dpp ligands in a slightly distorted tetrahedral geometry (Fig. 3a), with the Zn-O distances of 1.989(2) and 1.995(2)Å , respectively, and Zn-N distances of 2.045(3)Å and 2.021(2)Å , respectively, which are all shorter than that of 2. The bond angles around the Zn(II) ion range from 99.23(8) to 124.46(10)˚ . It is noteworthy that both the carboxylate groups of L2- ligand in 3 adopt a mono-dentate bridging mode to connect two adjacent zinc ions to generate a 1D Zn-carboxylate chain along the c axis (Fig. 3b), which is similar to that of 1, but different from that of 2. These 1D chains are bridged by the dpp ligands to form a 2D network along the a axis (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, there are weak interactions of C-H• • •N H-bond between the tetrazolyls of L2- ligands and the assistant dpp ligands, which further connect the 2D coordination layers into a 3D porous supramolecular architecture (Fig. 3d). Moreover, the Zn(II) ions could be simplified as 4- connected nodes and both the carboxylate and dpp ligands could be considered as linkers between the nodes. Based on this simplification, the 2D layer could be considered as sql topology with the vertex symbol 44 (Fig. 3d).

In these complexes, the pyridine-analogs all adopt their usual coordination mode as we expected: 2, 2'-bipy serves as blocking ligand with bidentate chelating mode acting as terminal supplement of coordination for the 1D Zn(II)-carboxylate chain in 1, while 4, 4'-bipy molecules adopt linear bridging coordination mode to connect the 1D Zn(II)-carboxylate double chains of 2 into a 2D double-layer structure and bpp adopts a twisted bridging mode to connect two Zn(II) ions as flexible spacers creating the 2D network of 3. Although the auxiliary ligands have obvious influence on the construction of such a Zn(II)-carboxylate coordination system, the nature of the primary ligand, especially for the introduction of neutral tetrazolyl also plays an important role on the structural formation of 1-3. The primary ligand L2- coordinated with the Zn(II) ion all form the linear 1D Zn(II)- carboxylate chain in 1-3, but show different coordination modes: In 1 and 3, one L2- ligand links two Zn(II) ions with the carboxyls both adopting mono-dentate bridging mode forming 1D chain, which is similar to related reports in the literature [21, 34, 40, 41]. Aswe had not anticipated, one L2- ligand bridges three Zn(II) ions into a 1D double-chain in 2, with one carboxyl adopting bidentate chelating mode and the other adopting bidentate bridging mode. As far as we know, such coordination mode is seldom reported in the coordination system with 1, 3-benzenedicarboxylates or its derivatives.

On the other hand, it is noteworthy that the 2D supramolecular framework of 1 is generated via the p-p interactions between the tetrazole rings of L2- ligands, while the 3D porous supramolecular architecture of 3 is formed by the interaction of H-bonds between the tetrazolyls and the assistant dpp ligands. Thus, the weak intermolecular forces may stabilize certain architecture and guide the self-assembly of such Zn(II)-carboxylate/pyridine-derivative systems. Although there is no weak interaction existing in 2 to make the 2D coordination structure into a higher dimensional network, the steric hindrance of tetrazolyl may influence the coordination mode of L2- ligand, finally leading to the formation of Zn(II)-carboxylate double-chain which is different from the similar coordination system in related reports [34, 40, 42].

In order to investigate the thermal stability of 1-3, thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) were carried out from 25-600 °C. As shown in the TGA profiles (Fig. S2 in Supporting information), all the complexes have good thermal stabilities. Complex 1 is stable until 90 °C and then the gradual weight loss of 11.5% from 90 °C to 300 °C corresponds to the loss of dissociative DMF molecules (Calcd. 12.2%). With the loss of coordinated DMF molecules and 2, 2'-bipy ligands, the entire framework of 1 decomposes quickly from 300 °C till 530 °C. Complex 2 is stable until 207 °C and gradual decomposes till 484 °C. The loss of the uncoordinated solvent molecules may proceed with the decomposing of the framework. For 3, the gradual loss of 6.1% (Calcd. 6.8%) from 142 °C to 284 °C corresponds to the loss of the two dissociative water molecules and the framework starts to decompose till 523 °C.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3.(a) The coordination environment of Zn(II) center (symmetry codes: A -x, -y + 1, -z + 1; B -x + 1, -y + 1, -z + 1; C x, y + 1, z); (b) the 2D network of 3; (c) the 3D supramolecular structure of 3 formed by C–H• • •N interactions; (d) schematic view of the (4,4) topology of the 2D network of 3 (Zn(II) ion is shown as pink ball). | |

|

Download:

|

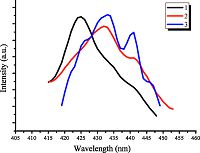

| Fig. 4.Emission spectra of complexes 1–3 in solid state at room temperature. | |

Luminescent properties: Metal-organic compounds with d10 ions have been found to be promising luminescent materials for their potential applications, such as light-emitting materials [43, 44, 45]. In this work, the emission spectra of complexes 1-3 and free ligands H2L have been investigated in the solid state at r.t. The complexes exhibit similar emission bands in the visible light region with emission maximum at 425 nm (for 1 λex = 371 nm), 432 nm (for 2 λex = 381 nm), 433 nm (for 3 λex = 381 nm) (Fig. 4), respectively, which indicate that the emissions should be attributed to similar characteristics. Considering the components and structures of these complexes, such emissions are neither metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT), nor ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT). Furthermore, the obvious blue shift could be observed when the emissions of complexes were comparedwith that of free ligandH2L (Em = 482 nm, λex = 359 nm, Fig. S3 in Supporting information). Though the examples of blueshifted emission for complexes are rather rare compared with red-shifted ones, this phenomenon has been well reported and investigated by Zhou’s group [45]. Compared to the free ligand H2L, the blue-shifted emissions of complexes 1-3 we reported herein could be explained in a similar way: an extended delocalized conjugated system could be postulated based on the abundant hydrogen bond interaction sites on the ligand. On the other hand, the coordination of ligand to the metal ions results in the torsion of single bonds in the ligand, which could result in the breakdown of the delocalized conjugated system and the observed blue-shifted emissions. Therefore, the emissions of 1-3 could be assigned to the intraligand (n-π* or π-π*) transitions emission states of L2- which disturbed by the auxiliary ligands and coordinated metal ion [21, 46].

4. ConclusionIn summary, three novel Zn(II) complexes based on 5-(1H-tetrazol- 1-yl) isophthalic acid, with pyridine-analogs as auxiliary organic ligands, have been synthesized, characterized and their luminescence properties have been investigated. Structural analyses show that complexes 1-3 possess varying frameworks from 1D chain to 3D supramolecular network. Such obvious structure-tuning could mainly be attributed to the introduction of tetrazolyl into isophthalic acid as well as the different structure of auxiliary ligands, which shows a good example of crystal engineering.

AcknowledgmentsThis work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (No. B2012202019) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21206027).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2015.05.025.

| [1] | F.J.M. Hoeben, P. Jonkheijm, E.W. Meijer, A.P.H.J. Schenning, About supramolecular assemblies of pi-conjugated systems, Chem. Rev. 105 (2005) 1491–1546. |

| [2] | S.R. Zheng, Q.Y. Yang, Y.R. Liu, et al., Assembly of CdI2-type coordination networks from triangular ligand and octahedral metal center:topological analysis and potential framework porosity, Chem. Commun. (2008) 356-358. |

| [3] | X.L. Tong, T.L. Hu, J.P. Zhao, et al., Chiral magnetic metal-organic frameworks of MnII with achiral tetrazolate-based ligands by spontaneous resolution, Chem. Commun. 46(2010) 8543-8545. |

| [4] | K.H. He, Y.W. Li, Y.Q. Chen, Z. Chang, A new 8-connected self-penetrating metal-organic framework based on dinuclear cadmium clusters as secondary building units, Chin. Chem. Lett. 24(2013) 691-694. |

| [5] | J.C. Noveron, M. Soo Lah, R.E. Del Sesto, et al., Engineering the structure and magnetic properties of crystalline solids via the metal-directed self-assembly of a versatile molecular building unit, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124(2002) 6613-6625. |

| [6] | O. Maury, H. Le Bozec, Molecular engineering of octupolar NLO molecules and materials based on bipyridyl metal complexes, Acc. Chem. Res. 38(2005) 691-704. |

| [7] | C.H. Huang, S.H. Gou, H.B. Zhu, W. Huang, Cleavage of C-S bonds with the formation of a tetranuclear Cu(I) cluster, Inorg. Chem. 46(2007) 5537-5543. |

| [8] | S. Rau, B. Schä fer, D. Gleich, et al., A supramolecular photocatalyst for the production of hydrogen and the selective hydrogenation of tolane, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45(2006) 6215-6218. |

| [9] | S.M. Zhang, Z. Chang, T.L. Hu, X.H. Bu, New three-dimensional porousmetal organic frameworkwith tetrazole functionalized aromatic carboxylic acid:synthesis, structure, and gas adsorption properties, Inorg. Chem. 49(2010) 11581-11586. |

| [10] | S. Kume, M. Murata, T. Ozeki, H. Nishihara, Reversible photoelectronic signal conversion based on photoisomerization-controlled coordination change of azobenzene-bipyridine ligands to copper, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127(2005) 490-491. |

| [11] | K. Kinbara, T. Aida, Toward intelligent molecular machines:directed motions of biological and artificial molecules and assemblies, Chem. Rev. 105(2005) 1377-1400. |

| [12] | L. Wang, R. Zhao, L.Y. Xu, et al., The synthesis, structure, and magnetic properties of two novel manganese(II) azido/formate coordination polymers with isonicotinic acid N-oxide as a coligand, CrystEngComm. 16(2014) 2070-2077. |

| [13] | R.M. Wen, S.D. Han, H. Wang, Y.H. Zhang, Synthesis, structure and magnetic properties of manganese(II) coordination polymer with azido and zwitterionic dicarboxylate ligand, Chin. Chem. Lett. 25(2014) 854-858. |

| [14] | S. Banfi, L. Carlucci, E. Caruso, G. Ciani, D.M. Proserpio, Using long bis(4-pyridyl) ligands designed for the self-assembly of coordination frameworks and architectures, J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. (2002) 2714-2721. |

| [15] | Y.B. Xie, C. Zhang, J.R. Li, X.H. Bu, Polymeric silver(I) complexes with pyridyl dithioether ligands:experimental and theoretical investigations on the coordination properties of the ligands, Dalton Trans. (2004) 562-569. |

| [16] | S.M. Zhang, T.L. Hu, J.R. Li, J.L. Du, X.H. Bu, Silver(I) coordination architectures with quinoxaline-based N,S-donor ligands:structures and luminescent properties, CrystEngComm. 10(2008) 1595-1604. |

| [17] | M.A. Withersby, A.J. Blake, N.R. Champness, et al., Solvent control in the synthesis of 3,6-bis(pyridin-3-yl)-1,2,4,5-tetrazine-bridged cadmium(II) and zinc(II) coordination polymers, Inorg. Chem. 38(1999) 2259-2266. |

| [18] | N.P. Chatterton, D.M.L. Goodgame, D.A. Grachvogel, et al., Influence of the counteranion on the formation of polymeric networks by metal complexes of hexamethylenebis(acetamide), Inorg. Chem. 40(2001) 312-317. |

| [19] | Z. Chang, D.S. Zhang, Q. Chen, et al., Rational construction of 3D pillared metal-organic frameworks:synthesis, structures, and hydrogen adsorption properties, Inorg. Chem. 50(2011) 7555-7562. |

| [20] | X. Zhang, L. Hou, B. Liu, et al., Syntheses, structures, and luminescent properties of six new zinc(II) coordination polymers constructed by flexible tetracarboxylate and various pyridine ligands, Cryst. Growth Des. 13(2013) 3177-3187. |

| [21] | X. Zhu, Q. Chen, Z. Yang, B.L. Li, H.Y. Li, Tuning zinc(II) coordination polymers based on bis(1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)ethane and 5-substituted 1,3-benzenedicarboxylates:syntheses, structures and properties, CrystEngComm. 15(2013) 471-481. |

| [22] | Z. Chen, B. Zhao, Y. Zhang, W. Shi, P. Cheng, Construction and characterization of several new lanthanide-organic frameworks:from 2D lattice to 2D Double-layer and to porous 3D net with interweaving triple-stranded helixes, Cryst. Growth Des. 8(2008) 2291-2298. |

| [23] | S.M. Zhang, T.L. Hu, J.L. Du, X.H. Bu, Tuning the formation of copper(I) coordination architectures with quinoxaline-based N,S-donor ligands by varying terminal groups of ligands and reaction temperature, Inorg. Chim. Acta 362(2009) 3915-3924. |

| [24] | Y.L. Yao, L. Xue, Y.X. Che, J.M. Zheng, Syntheses, structures, and characterizations of two pairs of Cd(II)-5-aminotetrazolate coordination polymers, Cryst. Growth Des. 9(2008) 606-610. |

| [25] | X.C. Huang, J.P. Zhang, X.M. Chen, A new route to supramolecular isomers via molecular templating:nanosized molecular polygons of copper(I) 2-methylimidazolates, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126(2004) 13218-13219. |

| [26] | M.O. Awaleh, A. Badia, F. Brisse, X.H. Bu, Synthesis and characterization of silver(I) coordination networks bearing flexible thioethers:anion versus ligand dominated structures, Inorg. Chem. 45(2006) 1560-1574. |

| [27] | T.L. Hu, Y. Tao, Z. Chang, X.H. Bu, Zinc(II) complexes with a versatile multitopic tetrazolate-based ligand showing various structures:impact of reaction conditions on the final product structures, Inorg. Chem. 50(2011) 10994-11003. |

| [28] | C.V. Krishnamohan Sharma, G.A. Broker, J.G. Huddleston, et al., Design strategies for solid-state supramolecular arrays containing both mixed-metalated and freebase porphyrins, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121(1999) 1137-1144. |

| [29] | D. Guo, K.L. Pang, C.Y. Duan, C. He, Q.J. Meng, Design and crystal structures of triple helicates with crystallographic idealized D3 symmetry:the role of side chain effect on crystal packing, Inorg. Chem. 41(2002) 5978-5985. |

| [30] | L. Pan, M.B. Sander, X.Y. Huang, et al., Microporous metal organic materials:promising candidates as sorbents for hydrogen storage, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126(2004) 1308-1309. |

| [31] | S.S.Y. Chui, S.M.F. Lo, J.P.H. Charmant, A.G. Orpen, I.D. Williams, A chemically functionalizable nanoporous material, Science 283(1999) 1148-1150. |

| [32] | D.K. Kumar, A. Das, P. Dastidar, One-dimensional chains, two-dimensional corrugated sheets having a cross-linked helix in metal-organic frameworks:exploring hydrogen-bond capable backbones and ligating topologies in mixed ligand systems, Cryst. Growth Des. 6(2006) 1903-1909. |

| [33] | Y.F. Zhou, F.L. Jiang, D.Q. Yuan, et al., Copper complex cation templated gadolinium(III)-isophthalate frameworks, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43(2004) 5665-5668. |

| [34] | F.N. Dai, H.Y. He, D.L. Gao, et al., Self-assembly of 2D zinc metal-organic frameworks based on mixed organic ligands, Inorg. Chim. Acta 362(2009) 3987-3992. |

| [35] | F. Nouar, J.F. Eubank, T. Bousquet, et al., Supermolecular building blocks (SBBs) for the design and synthesis of highly porous metal-organic frameworks, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130(2008) 1833-1835. |

| [36] | S.V. Voitekhovich, A.N. Vorobév, P.N. Gaponik, O.A. Ivashkevich, Synthesis of new functionally substituted 1-R-tetrazoles and their 5-amino derivatives, Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 41(2005) 999-1004. |

| [37] | A.X.S. Bruker, SAINT Software Reference Manual, Madison, WI, 1998. |

| [38] | G.M. Sheldrick, SADABS, Siemens Area Detector Absorption Corrected Software, University of Göttingen, Germany, 1996. |

| [39] | M. O'Keeffe, M.A. Peskov, S.J. Ramsden, O.M. Yaghi, The Reticular Chemistry Structure Resource (RCSR) database of, and symbols for, crystal nets, Acc. Chem. Res. 41(2008) 1782-1789. |

| [40] | L. Xu, G.C. Guo, B. Liu, M.S. Wang, J.S. Huang, 2-D open frameworks and blue fluorescence of two new zinc coordination polymers with mixed ligands, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 7(2004) 1145-1149. |

| [41] | L.F. Ma, Y.Y. Wang, J.Q. Liu, et al., Delicate substituent effect of isophthalate tectons on the structural assembly of diverse 4-connected metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), CrystEngComm. 11(2009) 1800-1802. |

| [42] | M. Chen, Y. Lu, J. Fan, et al., High structural diversity controlled by temperature and induction agent, CrystEngComm. 14(2012) 2015-2023. |

| [43] | D.M. Ciurtin, N.G. Pschirer, M.D. Smith, U.H.F. Bunz, H.C. zur Loye, Two luminescent coordination polymers with a triple-helix structure:HgX2(C31H24N2)·CH2Cl2(X=Cl and Br), Chem. Mater. 13(2001) 2743-2745. |

| [44] | R.L. Sang, L. Xu, A series of single, double, and triple Me2biim-bridged dinuclear, trinuclear, and polymeric complexes:syntheses, crystal structures, and luminescent properties, Inorg. Chem. 44(2005) 3731-3737. |

| [45] | Z.W. Wei, Z.Y. Gu, R.K. Arvapally, et al., Rigidifying fluorescent linkers by metal-organic framework formation for fluorescence blue shift and quantum yield enhancement, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(2014) 8269-8276. |

| [46] | K.L. Zhang, C.T. Hou, J.J. Song, et al., Temperature and auxiliary ligand-controlled supramolecular assembly in a series of Zn(II)-organic frameworks:syntheses, structures and properties, CrystEngComm. 14(2012) 590-600.electrospray tandem mass spectrometry, Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 35(2007) 969-972. |

2015, Vol.26

2015, Vol.26