b Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA;

c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

Since Gorham invented the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) process of preparing poly(p-xylylene) from [2.2]paracyclophane [1],CVD polymerization has been widely used as a substrateindependent conformal thin film polymer coating and surface modification technique [2]. The applications of the functional CVD coatings decouple the surface chemistry from the bulk material composition [3]. CVD polymerization is also a solvent-free [2],lowtemperature deposition process,which shows high level of control over chemical composition and good adhesion to the substrates [4]. The well-defined CVD process can yield chemically robust polymer films with superb biocompatibility. In the past few decades,CVD polymerization of substituted [2.2]paracyclophanes has been used to create a wide array of functionalized poly(pxylylenes) with different functional groups such as alcohols [2, 5], amines [6],aldehyde [7],ketones [8],esters [9],maleimide [10], anhydride [11],active ester [12],benzophenone [8],alkynes [13] and 2-bromoisobutyryl groups [14]. Of all the CVD polymer films,poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) deserves special attention, because it possesses remarkable reactivity towards azidefunctionalized moieties(‘‘click’’ chemistry),which is orthogonal to many other bioconjugation reactions [15].

Click chemistry,since its first introduction in 2001,has been extensively studied and widely used for producing compounds, reagents and biomolecules for chemical and biomedical applications [16, 17, 18, 19]. A number of highly efficient and selective reactions have been classified as click reactions [20]. Of all the reactions that meet the requirements of click reactions,the Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction between an azide and a terminal alkyne to yield 1,2,3-triazoles is undoubtedly the most popular example of a click reaction [21]. The ease of synthesis of molecules with the alkyne and azide functionalities,along with the simple reaction conditions,kinetic stability,superior regioselectivity,excellent yield and biocompatibility,make these complementary coupling partners particularly attractive [18, 22, 23].

When utilizing poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) for click reactions,the stability of the polymer thin films,especially the stability of the alkyne groups at elevated temperature or under ambient storage conditions is an important subject to study [24]. Recent work suggests poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) and its precursor both started to crosslink at 160℃ [25]. There was an exothermic peak at 250℃ in differential scanning calorimetry (DSC),when the scan rate was 10℃/min [25]. At 380℃,the alkyne functional groups completely disappeared [25].

In this paper,the thermal and environmental stability of the CVD-produced poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) thin film is investigated by FTIR,TGA and fluorescence microscopy. Furthermore,Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction is conducted in a series of experiments to identify optimal reaction parameters. The optimization experiments are meant to provide guidance or those who use Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction to immobilize biomolecules on the polymer coating surface. 2. Experimental

CVD polymerization and characterization: The precursor 4- ethynyl[2.2]paracyclophane was synthesized as reported previously [13]. For CVD polymerization,200 mg precursor was sublimed at 80℃ under vacuum and pyrolyzed into corresponding diradicals at 660℃. The intermediates spontaneously polymerized upon condensation onto the substrate surface on a rotating,cooled sample holder (13℃) inside a deposition chamber with a wall temperature of 120℃. A constant argon flow of 20 standard cubic centimetres per minute (sccm) was used as the carrier gas. The pressure was 0.08 Torr with the argon gas flow. FTIR spectroscopy was performed on a Nicolet 6700 spectrometer with a specular aperture grazing angle (SAGA) accessory with an 808 fixed angle of incidence. The FTIR measurement resolution was 4 cm-1. TGA test was performed on a TA instruments Discovery TGA,with the temperature ramped from room temperature to 800℃ at a rate of 20℃/min. TGA was carried out in nitrogen atmosphere with a purge rate of 25 mL/min. 2.1. Annealing process

Poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) coated samples were annealed at 0.08 Torr with 20 sccm argon flow. The heating temperature was raised from room temperature to a set temperature (100℃ or 150℃) at a rate of 5℃/min. Then the temperature was maintained at the set temperature for 1 h. We selected two annealing temperatures below the crosslinking temperature (160℃) of the poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) in this study. The samples were cooled to room temperature before venting the vacuum system to take out the samples. 2.2. Click reaction process

Poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene)-coated glass coverslips were incubated in a mixed aqueous solution of biotin-PEG3- azide,copper sulfate and sodium ascorbate for 2 h,followed by rinsing with deionized water twice,EDTA solution (0.01 g/mL) once,deionized water twice and PBS (Phosphate buffered saline) (0.01 mol/L) once. The thoroughly rinsed coverslips were incubated in BSA (bovine serum albumin) solution (1 mg/mL in PBS) for 30 min and then in Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated streptavidin solution (PBS solution with 0.01 mg/mL Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated streptavidin and 1 mg/mL BSA) for 1 h. BSA was used to stabilize the streptavidin protein and to prevent non-specific binding of streptavidin on the polymer surface. Subsequently,the coverslips were rinsed by PBS twice and deionized water three times. The airdried coverslips were imaged in a FluorChem M digital darkroom (ProteinSimple,USA). In order to optimize the click reaction conditions,we carried out experiments to study the effects of different reaction conditions. Each different sample set with a different reaction condition was tested in triplicate. A Student’s t-test was performed on the fluorescence intensity data from different sample sets to determine whether there were statistically significant differences. In this study,we require a p-value below 0.05 for two sets of data to be considered significantly different. 3. Results and discussion

3.1. CVD polymerization and characterization

As shown in Scheme 1,4-ethynyl[2.2]paracyclophane was sublimated at 80℃ under a reduced pressure of 0.08 Torr. The argon carrier gas transported the vaporized precursor into the pyrolysis zone,which was heated to 660℃ to ensure cleavage of the C-C bonds of the bridges,resulting in reactive species which spontaneously polymerized upon adsorption onto the cooled substrates,which was maintained at 13℃. This process resulted in conformal and homogenous films of poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co- p-xylylene).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme. 1. CVD polymerization process for preparing poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co- p-xylylene). | |

FTIR spectroscopy was used to assess the chemical structure of the synthesized polymer. The FTIR spectrum clearly shows the terminal alkyne C≡C-H stretching band at 3285 cm-1 and -C≡C- stretching band at 2101 cm-1,which are characteristic of the terminal alkyne groups. No signs of decomposition or side reactions were observed. This is in excellent accordance with the literature [26]. 3.2. Thermal and environmental stability of poly(4-ethynyl-pxylylene-co-p-xylylene)

The stability of the polymer thin films is of great importance to their usage,since it is not possible to always use the polymer films immediately after preparation. In this paper,both the thermal and environmental stability of poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) polymer films were tested by FTIR and TGA. Huisgen 1,3- dipolar cycloaddition reaction is also an effective way of testing the existence of alkyne groups. After the click reaction,biotin was immobilized through the triazole linker,followed by binding of the Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated streptavidin. The fluorescence intensity reflects the degree of the alkyne group retention,thus indicating the thermal/environmental stability of the poly(4- ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) films. In all the stability tests, we used 0.45 mmol/L biotin-PEG3-azide,1 mmol/L copper sulfate and 25 mmol/L sodium ascorbate for the click reactions. 3.2.1. Thermal stability of poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene)

In this study,thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and thermal annealing [25] were both used for testing the thermal stability of the CVD coated films. The poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) films were annealed under vacuum with argon flow at 100℃ and 150℃ respectively for 1 h. The TGA results (Fig. 1) show that poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) had no obvious weight loss in nitrogen until the environmental temperature approached 392℃. Fig. 2 shows the FTIR spectra of poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylyleneco- p-xylylene)-coated surfaces before and after thermal annealing. F$()1DFGIST[]cehm romthe FTIR spectra,we can see that after annealing at 100℃,the C≡C-H stretching band at 3285 cm-1 and -C≡C- stretching band at 2101 cm-1 were almost the same as the coating without annealing. However,after annealing at 150℃,the -C≡C- stretching band was significantly reduced,probably due to the crosslinking of the ethynyl groups [25].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. TGA curve of the poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene)-coated samples. The polymer undergoes decomposition at 392℃ in nitrogen. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. FTIR spectra of poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene)-coated samples before and after thermal annealing. The annealed samples were heated at 100℃ or 150℃ at 0.08 Torr in argon for 1 h. | |

Click reaction was also conducted to further test the thermal stability of the alkyne functional groups. Coverslips coated with poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) were incubated in the click reaction solution for 2 h,followed by thorough rinsing and Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated streptavidin immobilization. After the click reaction and the streptavidin immobilization,the fluorescence intensities of different sample sets were analyzed statistically. p value is used to determine whether there is any significant difference between two sets of samples. In this study, we consider p value less than 0.05 indicating two sets of data significantly different. The analysis of fluorescence intensities (Fig. 3) shows that the reactivity of the poly(4-ethynyl-pxylylene- co-p-xylylene) film annealed at 100℃ for 1h is not significantly different than the as-deposited film (p > 0.05). On the other hand,annealing at 150℃ for 1 h significantly reduced the reactivity of the film (p < 0.05). These results agree with what we observed from the FTIR experiments.

|

Download:

|

|

| Fig. 3. Fluorescence intensity analysis of poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene)- coated glass coverslips (with or without annealing) after the click reaction. The purpose was to test the thermal stability of the alkyne functional groups on the polymer surface. The samples with as-deposited coatings and the samples annealed at 100℃ are not significantly different (p > 0.05),while the samples annealed at 150℃ are significantly different from the other two sets of samples (p < 0.05). | ||

Environmental stability is vital to the usage of a material since the poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) film may be stored and used in different environments. In order to test environmental stability,the polymer coatings were placed in distilled water, under ambient storage conditions or in a desiccator with humidity less than 5% for several days respectively. FTIR was used to monitor the polymer coatings from time to time. The ratios of C≡C-H (3285 cm-1) to C55C (benzene ring,1492 cm-1) peak in FTIR spectra (Fig. S1 in supporting information) show no obvious change,suggesting that the CVD coatings are stable under all the above-mentioned storage conditions. Again,the click reaction was conducted to test the functional group reactivity on the polymer surface. The statistical analysis of fluorescence intensities (Fig. 4) also shows that poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) is stable under the three different storage conditions.

|

Download:

|

||

| Fig. 4. Fluorescence intensity analysis of poly(4-ethynyl-co-p-xylylene)- coated samples placed in different environments for 3 days followed by the surface click reaction. p values between the intensities from any two sets of samples are all larger than 0.05. The results show that the alkyne functional groups of poly(4- ethynyl-co-p-xylylene) are stable under all the three different storage conditions. | |||

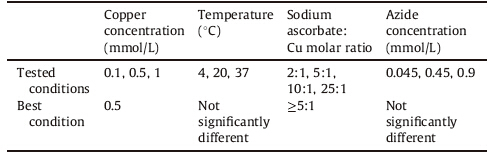

When optimizing the click reaction condition on the poly(4- ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene)-coated surfaces,many parameters need to be taken into account,such as the concentration of the copper catalyst,the concentration of the azide molecule,the concentration of the reducing agent (sodium ascorbate for this study) and the reaction temperature. In this paper,the effect of these parameters was systematically studied. Table 1 shows the optimized experimental conditions for all parameters.

| Table 1 ‘‘Click’’ reaction optimization on the poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene)- coated surface. |

Copper(I) ion is the catalyst of Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction. A large amount of copper(I) sources can be utilized in this reaction,like copper bromide,copper chloride, copper acetate and some coordination complexes [27]. In this study,copper(II) sulfate aqueous solution,which can be reduced into copper(I) in the presence of sodium ascorbate,was chosen as the copper source. We studied three different copper concentrations: 0.1 mmol/L,0.5 mmol/L and 1 mmol/L. The analysis of fluorescence intensities shows that higher copper concentrations lead to better click reaction results (Fig. S2 in Supporting information). However,the fluorescence intensities after the click reactions show no significant differences statistically when using 0.5 mmol/L or 1 mmol/L copper catalyst,thus 0.5 mmol/L copper concentration seems to be adequate. High copper concentration may have solubility issue and difficult to remove by water or PBS once adhering to the coating surface. For biomedical applications,lower copper concentration is necessary to minimize the toxicity. In that case,copper concentration can be reduced to a reasonable amount [28].

Due to the wide applications of the alkyne-azide click reaction, more and more azide functionalized molecules are commercially available. In this study,biotin-PEG3-azide was used for the click reaction with the alkyne functionalized poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene- co-p-xylylene)-coated samples. Three different azide molecule concentrations were tested: 0.045 mmol/L,0.45 mmol/L and 0.9 mmol/L. Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated streptavidin was immobilized specifically to the biotin bound to the surface [26]. The fluorescence intensities of the samples incubated in solutions with different biotin-PEG3-azide concentrations were similar (Fig. S3 in Supporting information). So it seems that the azide molecule concentration did not play a significant role on the surface click reactions under the given experimental conditions.

Sodium ascorbate,a mild reducing agent,was introduced in Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction to remove oxygen from the aqueous solution and prevent the cuprous ions from being oxidized [27, 29]. It is a common reducing agent for click chemistry. In this paper,the concentration of sodium ascorbate is presented using the ratio of sodium ascorbate concentration to copper concentration as it is more meaningful than using the absolute concentration value. Four different ratios were tested: 2:1,5:1, 10:1 and 25:1. The results (Fig. S4 in Supporting information) show that sodium ascorbate concentration to copper concentration of 2:1 was not adequate for the click reaction to proceed at room temperature. It is reported that insufficient reducing agent concentration could lead to incompletion of the click reaction [30]. The ratio of 5:1 provided excellent reaction results. When the ratio is larger than 5:1,the results did not show significant further improvement.

Few articles discussed the effect of temperature on Huisgen 1,3- dipolar cycloaddition reaction. González et al. [31] performed experiments at different temperatures using bases under oxidative conditions. They found that temperature played an important role in producing different percentage of triazoles and bistriazoles under the special reaction conditions [31]. In this study,we were trying to optimize the reaction conditions for immobilizing biomolecules on the surface,thus we selected three different temperatures: 4℃,room temperature (25℃) and 37℃. The results show that temperature did not have obvious effect on our bioconjugation reaction (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). A possible explanation is that the copper catalyst could effectively lower the energy barrier of the reactions under the reaction conditions we used,thus temperature would not change the reaction kinetics. 4. Conclusion

In summary,poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) coatings prepared by CVD polymerization were stable under common storage conditions. The alkyne functional groups were thermally stable when annealed at up to 100℃ at 0.08 Torr in argon. The TGA analysis in nitrogen atmosphere show no obvious weight loss until the temperature reached 392℃. The parameters of click reaction on the polymer surface were optimized when copper concentration was 0.5 mmol/L and the ratio of sodium ascorbate to copper concentration was 5:1. The azide molecule concentration and temperature did not have obvious effect on the click reactionwith the experimental conditionwe used. The stability of the poly(4-ethynyl-p-xylylene-co-p-xylylene) and the surface click reaction optimization are both important to ensure the quality of biomolecule immobilization strategies for surface modification.

AcknowledgmentsWe acknowledge support from DTRA,under project HDTRA1- 12-1-0039 and the Army Research Office (ARO) under Grant W911NF-11-1-0251. Y. Liang sincerely acknowledges support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found,in the online version,at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2015.01.018.

| [1] | W.F. Gorham, A new, general synthetic method for the preparation of linear polyp- xylylenes, J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 4 (1966) 3027-3039. |

| [2] | J. Lahann, R. Langer, Novel poly(p-xylylenes): thin films with tailored chemical and optical properties, Macromolecules 35 (2002) 4380-4386. |

| [3] | M.E. Alf, A. Asatekin, M.C. Barr, et al., Chemical vapor deposition of conformal, functional, and responsive polymer films, Adv. Mater. 22 (2010) 1993-2027. |

| [4] | A. Greiner, Poly(1,4-xylylene)s: polymer films by chemical vapour deposition, Trends Polym. Sci. 5 (1997) 12-16. |

| [5] | J. Lahann, R. Langer, Surface-initiated ring-opening polymerization of epsiloncaprolactone from a patterned poly(hydroxymethyl-p-xylylene), Macromol. Rapid Commun. 22 (2001) 968-971. |

| [6] | J. Lahann, I.S. Choi, J. Lee, K.F. Jenson, R. Langer, A new method toward microengineered surfaces based on reactive coating, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40 (2001) 3166-3169. |

| [7] | H. Nandivada, H.Y. Chen, J. Lahann, Vapor-based synthesis of poly[(4-formyl-pxylylene)- co-(p-xylylene)] and its use for biomimetic surface modifications, Macromol. Rapid Commun. 26 (2005) 1794-1799. |

| [8] | H.-Y. Chen, J. Lahann, Designable biointerfaces using vapor-based reactive polymers, Langmuir 27 (2011) 34-48. |

| [9] | J. Lahann, M. Balcells, H. Lu, et al., Reactive polymer coatings: a first step toward surface engineering of microfluidic devices, Anal. Chem. 75 (2003) 2117-2122. |

| [10] | M.-Y. Tsai, C.-Y. Lin, C.-H. Huang, et al., Vapor-based synthesis of maleimidefunctionalized coating for biointerface engineering, Chem. Commun. 48 (2012) 10969-10971. |

| [11] | Y. Elkasabi, M. Yoshida, H. Nandivada, H.-Y. Chen, J. Lahann, Towards multipotent coatings: chemical vapor deposition and biofunctionalization of carbonyl-substituted copolymers, Macromol. Rapid Commun. 29 (2008) 855-870. |

| [12] | X.P. Deng, J. Lahann, Orthogonal surface functionalization through bioactive vapor-based polymer coatings, J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 131 (2014) 40315. |

| [13] | H. Nandivada, H.Y. Chen, L. Bondarenko, J. Lahann, Reactive polymer coatings that "click", Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45 (2006) 3360-3363. |

| [14] | X. Jiang, H.Y. Chen, G. Galvan, M. Yoshida, J. Lahann, Vapor-based initiator coatings for atom transfer radical polymerization, Adv. Funct. Mater. 18 (2008) 27-35. |

| [15] | X. Deng, C. Friedmann, J. Lahann, Bio-orthogonal "double-click" chemistry based on multifunctional coatings, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50 (2011) 6522-6526. |

| [16] | X. Zhang, Y. Zhang, Applications of azide-based bioorthogonal click chemistry in glycobiology, Molecules 18 (2013) 7145-7159. |

| [17] | J.E. Moses, A.D. Moorhouse, The growing applications of click chemistry, Chem. Soc. Rev. 36 (2007) 1249-1262. |

| [18] | K.K. Ghosh, H.H. Ha, N.Y. Kang, Y. Chandran, Y.T. Chang, Solid phase combinatorial synthesis of a xanthone library using click chemistry and its application to an embryonic stem cell probe, Chem. Commun. 47 (2011) 7488-7490. |

| [19] | H. Kolb, M. Finn, K. Sharpless, Click chemistry: diverse chemical function from a few good reactions, Angew. Chem. 40 (2001) 2004-2021. |

| [20] | C.D. Hein, X. Liu, D. Wang, Click chemistry, a powerful tool for pharmaceutical sciences, Pharm. Res. 25 (2008) 2216-2230. |

| [21] | J.-F. Lutz, 1,3-Dipolar cycloadditions of azides and alkynes: a universal ligation tool in polymer and materials science, Angew. Chem. 46 (2007) 1018-1025. |

| [22] | M. Meldal, C.W. Tornoe, Cu-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition, Chem. Rev. 108 (2008) 2952-3015. |

| [23] | M.G. Finn, H.C. Kolb, V.V. Fokin, K.B. Sharpless, Click chemistry-definition and aims, Prog. Chem. 20 (2008) 1-5. |

| [24] | J.J. Senkevich, Stability of CVD-produced polymer thin films, Chem. Vapor Depos. 17 (2011) 170-172. |

| [25] | J.J. Senkevich, B.W. Woods, J.J. McMahon, P.I. Wang, Thermomechanical properties of parylene X, a room-temperature chemical vapor depositable crosslinkable polymer, Chem. Vapor Depos. 13 (2007) 55-59. |

| [26] | X.P. Deng, T.W. Eyster, Y. Elkasabi, J. Lahann, Bio-orthogonal polymer coatings for co-presentation of biomolecules, Macromol. Rapid Commun. 33 (2012) 640-645. |

| [27] | J.E. Hein, V.V. Fokin, Copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) and beyond: new reactivity of copper(I) acetylides, Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 (2010) 1302- 1315. |

| [28] | V. Hong, N.F. Steinmetz, M. Manchester, M.G. Finn, Labeling live cells by coppercatalyzed alkyne-azide click chemistry, Bioconjug. Chem. 21 (2010) 1912-1916. |

| [29] | V.V. Rostovtsev, L.G. Green, V.V. Fokin, K.B. Sharpless, A stepwise Huisgen cycloaddition process: copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective "ligation" of azides and terminal alkynes, Angew. Chem. 114 (2002) 2708-2711. |

| [30] | V. Hong, S.I. Presolski, C. Ma, M.G. Finn, Analysis and optimization of coppercatalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition for bioconjugation, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48 (2009) 9879-9883. |

| [31] | J. González, V.M. Pérez, D.O. Jiménez, et al., Effect of temperature on triazole and bistriazole formation through copper-catalyzed alkyne-azide cycloaddition, Tetrahedron Lett. 52 (2011) 3514-3517. |