Adjuvant radiotherapy for cancer patients degrades the biomechanical properties of adjacent healthy bone tissue,which results in increase of susceptibility to bone fracture in the affected region and even osteoradionecrosis. For example,it is estimated that 5%-15% of patients with head and neck cancer being treated by radiotherapy will develop symptoms of osteoradionecrosis (ORN) of the jaw and 3% of patients finally have ORN of the jaw [1, 2]. Recent reports also show post-radiation fracture incidence as high as 22% in patients with breast cancer and 24% in some populations of patients with soft-tissue sarcoma [3, 4, 5].

The underlying pathophysiology of radiation-induced bone damages remains poorly understood. ‘‘Three H’’,hypovascular, hypocelluar and hypoxic,has been used to describe the cellular and vascular response to radiotherapy [6],which results in suppression of the remodeling and healing capacity of bone. However,radiation damage to murine bone cannot be completely understood as depletion and recovery of cell populations. This problem suggests the likely involvement of ‘‘cell-independent,physicochemical erosion enabled by radiation damage to the organic and inorganic constituents of the matrix.’’ [7]. In addition,clinical studies showing that irradiation does not routinely decrease bone density further suggest intrinsic material abnormalities in the irradiated bone [8, 9]. These abnormalities,such as pathological collagen cross-links,altered mineral crystallinity and carbonation,are not detectable by conventional histology and computed tomography (CT) or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and require application of other techniques.

Over the past 12-15 years there has been increasing interest in the application of Raman spectroscopy to bone studies [10]. In comparison to Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy provides experimental advantages including spectroscopic microscopy with <1 μm lateral spatial resolution, applicability to fresh tissue and in vivo measurement capability. Because Raman provides both chemical and structural signatures of bone mineral and matrix,it can be used to quantify relevant mineral and matrix chemical composition and structural properties of bone,including bone mineral crystallinity,carbonate content,amount of mineral relative to matrix,the state of collagen cross-linking and the orientation of mineral crystallite and collagen fibrils. Alteration of these parameters can be easily monitored by Raman spectroscopy and could help explain radiotherapy-induced changes in bone material behavior.

In collaboration with other medical,dental and biomedical engineering research groups,the Morris laboratory at the University of Michigan has applied Raman spectroscopy to investigate a range of problems in bone tissue,such as age-related effects in biomechanical competence [11],composition problems in the Brtl mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta [12], correlation between bone composition and osteoporotic fracture outcomes [13],early detection of osteomyelitis [14],kinetics of early mineral deposition [15],heterotopic ossification [16, 17] and spatial detection of collagen cross-linking differences due to relative tissue age and effects of cross-link inhibition [18]. In this mini review,we will focus on our recent studies on radiationinduced bone damage and the effect of adjuvant therapy with radioprotectants such as amifostine (AMF) [19, 20, 21]. In an irradiated mouse tibial model,Raman spectroscopy was used to follow changes in both bone chemistry and structure during 26 weeks post-radiation recovery. We have also studied irradiated rat hemimandibles to elucidate radiation-induced chemical and structural differences and efficacy of amifostine adjuvant therapy at 8 and 18 weeks post-radiation. It should be noted that most previous studies on irradiated bone used either very high dose (>10 kGy) ionizing irradiation,employed for sterilization of allograft material [22, 23, 24] or low dose irradiation on excised bones or in total body irradiation models [25, 26, 27]. We used focal irradiation on the clinically relevant body regions of living animals with clinically relevant irradiation doses. Our studies are more applicable to the conditions of cancer radiotherapy than is earlier work. The results suμmarized in this review provide more insights into radiation-induced degradation of bone biomechanical properties and show that Raman spectroscopy can investigate and monitor both the adverse effects of radiation and the efficacy of therapeutic remediation of radioprotectant drugs on bone material quality. 2. Raman metrics for bone quality assessment

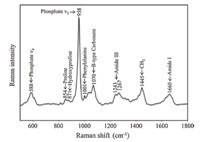

Bone is a heterogeneous and hierarchical material,which contains a mineral component,an organic matrix and water. The mineral is a carbonated hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2). The organic matrix mainly includes type I collagen with ~10% contributions from other proteins. Water accounts for ~20% weight of fresh bone tissue [28]. Both inorganic and organic constituents have specific Raman signatures that can be used to assess bone material quality. Fig. 1 shows a typical Raman spectrum of bone. The main bands due to mineral and matrix are labeled. Among them,the phosphate v1 band at~958 cm-1 and the B-type carbonate band at ~1070 cm-1 are often used to evaluate bone mineral properties. The amide I envelope at ~1660 cm-1 is an important indicator of protein secondary structural changes. The Raman metrics developed for analyzing bone material properties have been described in detail previously [10]. Briefly,the mineral to matrix ratio is determined by intensity of phosphate v1 band at ~958 cm-1 divided by the collagen protein band(s) (e.g. phenylalanine band or amide I band or proline and hydroxyproline bands). This ratio represents the relative amount of mineral in the examined region of bone tissue. Mineral crystallinity is inversely proportional to the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the phosphate v1 band (~958 cm-1) and provides the information on bone mineral structure and crystallite size. The carbonate to phosphate ratio is measured by the intensity ratio of the B-type carbonate band (~1070 cm-1) to the phosphate v1 band (~958 cm-1) and represents the relative carbonate content in bone mineral. The collagen cross-linking ratio is calculated by the intensity ratio of two sub-component bands (~1660/~1690 cm-1) in the amide I envelope. This ratio was first reported to indirectly measure the non-reducible/reducible collagen cross-link ratio in bone and reflects the secondary structural perturbation of collagen protein [29].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Raman spectrum of bone,with band assignments. | |

Bone is a heterogeneous and hierarchical material,which Bone structural organization affects bone quality. Polarized Raman spectroscopy provides structural information (e.g. orientation) of bone mineral and collagen fibrils [30, 31]. Most Raman bands of bone (Fig. 1) are sensitive to molecular orientation and to the polarization direction of incident laser light [19]. The intensities of the phosphate v1 at ~958 cm-1 and the amide I region at ~1660 cm-1 are used to calculate the depolarization ratios of bone mineral and matrix because both bands are strongly polarized [30, 32]. The depolarization ratio is defined by ρ = I(⊥)/I(//),where I(⊥) is the intensity of the perpendicular polarization component for the selected Raman band,and I(//) is the intensity of the parallel polarization component for the same band. A lower r value reflects a higher degree of molecular alignment or orientation. 3. Prolonged chemical and structural damage to irradiated mouse tibia

A longitudinal study has been performed in a mouse tibial model to evaluate radiation-induced bone damage during long term recovery [19]. Right tibiae of female BALB/F mice aged 12 weeks underwent a localized irradiation by 4 daily 5 Gy fractions. Mice were euthanized at 1,4,8,12 and 26 weeks postirradiation and both irradiated right tibiae and non-irradiated left tibiae (control) were harvested for Raman analysis. The detailed experimental conditions are given in [19]. Raman bone metrics, including mineral to matrix ratio,mineral crystallinity,carbonate to phosphate ratio,collagen cross-linking ratio,depolarization ratios of mineral and collagen,were calculated from Raman measurements performed on the proximal cortical bone surface of tibiae. Compared to control,irradiated bone showed several significant changes in these Raman metrics (Fig. 2). Hypermineralized bone tissue was observed at 4 weeks post-radiation, indicated by significant increase of mineral to matrix ratio (p = 0.048). The ratio declined significantly at 12 weeks (p < 0.001) and was not significantly different from controls at 1 (p = 0.949),8 (p = 0.608) and 26 weeks (p = 0.729). The deviations of mineral to matrix ratio from normal values would impair bone mechanical properties. After 26 weeks post-radiation,the ratio fully returned to the same level as the controls. The mineral crystallinity showed a similar changing pattern to mineral to matrix ratio with significant differences at 4 (p = 0.045) and 12 (p = 0.02) weeks,but no difference at 1 (p = 0.344),8 (p = 0.824) and 26 weeks (p = 0.152). Because crystallinity is closely correlated to crystal size and shape [33],alteration of crystallinity would induce local residual strains that may cause bone structural defects and increase fracture susceptibility [34]. The carbonate to phosphate ratio significantly decreased at 4 (p = 0.004) weeks and increased at 12 (p< 0.001) weeks post-radiation (Fig. 2). Abnormal carbonate content observed during radiation recovery probably reflects radiation-induced impaired bone mineralization and turnover.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Raman metrics for irradiated mouse tibia and control during 26 weeks post-radiation: (A) mineral to matrix ratio; (B) mineral crystallinity; (C) carbonate to mineral ratio; (D) collagen cross-link ratio; (E) depolarization ratio of mineral and (F) depolarization ratio of collagen matrix. Asterisk (*) represents statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). Detailed statistical analysis and results was given in [19]. Figure was adapted from [19]. | |

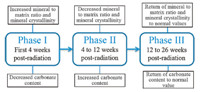

During 26 weeks post-radiation recovery,three different bone mineralization phases on the periosteal surface of irradiated mouse tibia have been proposed (Fig. 3). The early phase,involving the first 4 weeks post-radiation,showed the increased mineral to matrix ratio,decreased carbonate content and increased mineral crystallinity in the irradiated group. This phase likely corresponds histologically to the loss of osteoclasts and reflects different radiation tolerance of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. The second phase likely covers 4-12 weeks post-radiation,characterized by the decrease of mineral to matrix ratio and mineral crystallinity and increase of carbonate content. This phase may reflect partial recovery of vascularity with influx of the osteoclasts. The third phase starts from 12 weeks post-radiation and shows an increase of mineral to matrix ratio,mineral crystallinity and carbonate content until the metrics complete return to normal values at 26 week post-radiation. This observation may reflect better return of vascularity and recovery of osteoclasts and osteoblasts in mice compared to what might be seen in patients with post-radiation fractures.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Diagram of three mineralization phases proposed for the periosteal surface of irradiated mouse tibia during 26 weeks post-radiation recovery. | |

The collagen cross-linking ratios of irradiated bone were significantly higher than those of control at each measured time point. But continuous recovery to normal levels was clearly seen with increasing post-radiation time. The significantly higher values at 26 weeks (p = 0.005) implies that pathological crosslinks formed by radiation damage to collagen were incompletely resorbed,changing the interaction between collagen molecules and binding of mineral to collagen. These problems further degrade bone mechanical properties because formation of new tissue occurs on a defective scaffold.

The depolarization ratios of phosphate v1 for irradiated bone at 1 (p < 0.001),4 (p = 0.009) and 12 (p = 0.046) weeks post-radiation were significantly lower than those of the control (Fig. 2). When the depolarization ratios of the matrix were compared,a significant lower value was found in the irradiated bone at each time point (Fig. 2). The lower ratio indicates that irradiation results in bone with more ordered collagen fibrils and mineral crystallites along the tibial diaphysis. No difference between irradiated group and control was found for mineral depolarization ratio at 26 (p = 0.862) weeks,indicating mineral orientation in irradiated bone has fully restored. However,altered collagen fibril orientation in irradiated bone,like pathological collagen cross-links,is preserved at 26 (p = 0.02) weeks post-radiation.

In this mouse tibia model,extensive damage caused by irradiation in bone mineral and matrix is evident even in the early post-radiation period. There is some bone remodeling during 26 weeks recovery. While mineral orientation is fully restored, some damage to bone matrix persists for 26 weeks and may contribute to increased bone brittleness even at this time point. 4. Efficacy of amifostine protection on irradiated rat hemimandible

To remediate radiation-induced bone damage,many efforts have been undertaken in the past decades [35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]. One approach is the use of radioprotectants,which function as radical scavengers to minimize free radicals generated by irradiation of tissue. Among them,amifostine is of great interest because of its selective and superior protection on healthy cells from irradiation and acceptable toxicity [41]. Amifostine is a pro-drug which converts into a thiol metabolite by interaction with the cell membrane-bound alkaline phosphatase. The thiol metabolite scavenges free radicals and donates protons that contribute to DNA repair and stabilization [41, 42]. Amifostine is on formulary for prophylaxis against radiation-induced xerostomia and mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer [43, 44].

A rat hemimandible model has been used to evaluate efficacy of amifostine on bone composition and structure protection against radiation damage [20, 21]. Briefly,Sprague Dawley rat were randomly assigned to three experimental groups: control (n = 5), irradiated (XRT,n = 5),and amifostine-treated irradiated (AMF/ XRT,n = 5) groups. Both XRT and AMF/XRT groups underwent bioequivalent radiation to the left hemimandible of 70 Gy in 5 fractions. The AMF/XRT group received amifostine prior to radiation. After 8 and 18 weeks post-radiation,the rats were euthanized and the left hemimandibles were collected for Raman experiments. It was shown that in comparison to controls,radiation increases mineral to matrix ratio at 8 weeks postradiation (Fig. 4). The transient hypermineralization is similar to that observed in the mouse tibial model at 4 weeks post-radiation. Amifostine only partially restores the mineral to matrix ratio (p < 0.001) to control levels. A significant increase of mineral crystallinity (p < 0.001) and significant decrease of carbonate to phosphate ratio (p < 0.001) were found in the irradiated group compared to control,indicating formation of abnormally crystalline mineral when bone is subjected to radiation. In the AMF/XRT group,both mineral crystallinity (p = 0.246) and carbonate content (p = 0.157) are no different from those of control,demonstrating amifostine effects on bone mineral properties. The collagen crosslink ratio is significantly increased by radiation. But no statistically significant complete prevention with amifostine treatment (p = 0.994) was found. Depolarization ratios of both mineral and collage decreased after radiation. Only the mineral depolarization ratio held at normal by amifostine.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Raman metrics of irradiated rat mandible and control at 8 weeks post-radiation: (A) mineral to matrix ratio; (B) mineral crystallinity; (C) carbonate to mineral ratio; (D) collagen cross-link ratio; (E) depolarization ratio of mineral and (F) depolarization ratio of collagen matrix. Asterisk (*) represents statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). Detailed statistical analysis was given in [20]. Figure was adapted from [20]. | |

At 18 weeks post-radiation,no significant difference was found for all the Raman metrics but depolarization ratios amongst control,XRT and AMF/XRT groups,indicating recovery of the chemical composition to the normal values (Fig. 5). Damage to mineral and collagen orientations was still observable in the XRT group relative to control and AMF/XRT groups. Amifostine fully prevented structural damage by radiation. Interestingly,amifostine seems to more efficiently protect bone mineral rather than bone matrix. Thus,these results reveal unambiguously that radiation damages both bone mineral and collagen and demonstrate efficacy of amifostine treatment on radiation-induced bone damages. The findings provide deeper understanding of the mechanism of bone healing and regeneration after radiation.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Raman metrics of irradiated rat mandible and control at 18 weeks post-radiation: (A) mineral to matrix ratio; (B) mineral crystallinity; (C) carbonate to mineral ratio; (D) collagen cross-link ratio; (E) depolarization ratio of mineral and (F) depolarization ratio of collagen matrix. Asterisk (*) represents statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). Detailed statistical analysis was given in [21]. Figure was adapted from [21]. | |

Raman spectroscopy has been shown to be capable of monitoring radiation-induced changes in both bone chemical composition and structure in animal models at radiotherapy doses. Both bone mineral and collagen were damaged after irradiation. Some of the damage to matrix,such as,abnormal cross-links and collagen fibril orientation,was still present even at 26 weeks postradiation in the mouse tibial model and 18 week post-radiation in the rat mandible model. The remaining bone damage would theoretically compromise bone biomechanics,potentially leading to increased brittleness of irradiated bone and even osteoradionecrosis. Amifostine treatment provides important bone protection against radiation.

In addition,the Morris lab has developed in vivo Raman spectroscopy with non-invasive fiber optic probes [16, 45, 46, 47, 48].Using this technique,bone composition can be successfully monitored in vivo in mice and rats. Human subject validation of in vivo measurement has been started by comparing pre-operative noninvasive measurements with measurements of exposed bone tissue duringanterior cruciate ligament(ACL) tear repair.Most recently,the Morris lab has developed technology that allows calibration of measured Raman spectroscopic band intensities against phantoms and other external standards [49]. Refinements are underway to allow validation of spectroscopic measurements of bone mineral content against computed tomography and other accepted techniques. It is evident that these ongoing developments of in vivo noninvasiveRamantechnologyholdsthepotential foruse inhumans as a valuable diagnostic test for bothbonedamage fromradiationandthe efficacy of radioprotective drug adjuvant therapy. Also,this technique could be a complementary approach to conventional CT and DXA. These standard clinical assessment techniques have not been shown to predict radiation-induced fracture risk.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank our collaborators at University of Michigan and Upstate Medical University for their help with study design, preparation of specimens and discussion of the research.

| [1] | A.O. Hoff, B. Toth, M. Hu, G.N. Hortobagyi, R.F. Gagel, Epidemiology and risk factors for osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients, Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1218 (2011) 47-54. |

| [2] | D. Annane, J. Depondt, P. Aubert, et al., Chevret, Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radionecrosis of the jaw: a randomized, placebo-controlled, doubleblind trial from the ORN96 study group, J. Clin. Oncol. 22 (2004) 4893- 4900. |

| [3] | Y. Song, S. Wang, M. Chan, et al., Femoral fracture risk assessment after intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma using a novel mathematical model, in: 28th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, IEEE, New York, 2006, pp. 95-98. |

| [4] | J. Kelly, T. Damron, W. Grant, et al., Cross-sectional study of bone mineral density in adult survivors of solid pediatric cancers, J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 27 (2005) 248-253. |

| [5] | K.P. Dieckmann, U. Pichlmeier, Is risk of testicular cancer related to body size? Eur. Urol. 42 (2002) 564-569. |

| [6] | R.E. Marx, Osteoradionecrosis: a new concept of its pathophysiology, J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 41 (1983) 283-288. |

| [7] | D.E. Green, B.J. Adler, M.E. Chan, C.T. Rubin, Devastation of adult stem cell pools by irradiation precedes collapse of trabecular bone quality and quantity, J. Bone Miner. Res. 27 (2012) 749-759. |

| [8] | S. Dhakal, J. Chen, S. McCance, et al., Bone density changes after radiation for extremity sarcomas: exploring the etiology of pathologic fractures, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 80 (2011) 1158-1163. |

| [9] | J.D. Wernle, T.A. Damron, M.J. Allen, K.A. Mann, Local irradiation alters bone morphology and increases bone fragility in a mouse model, J. Biomech. 43 (2010) 2738-2746. |

| [10] | M.D. Morris, G.S. Mandair, Raman assessment of bone quality, Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 469 (2011) 2160-2169. |

| [11] | M. Raghavan, N.D. Sahar, D.H. Kohn, M.D. Morris, Age-specific profiles of tissuelevel composition and mechanical properties in murine cortical bone, Bone 50 (2012) 942-953. |

| [12] | K.M. Kozloff, A. Carden, C. Bergwitz, et al., Brittle IV mouse model for osteogenesis imperfecta IV demonstrates postpubertal adaptations to improve whole bone strength, J. Bone Miner. Res. 19 (2004) 614-622. |

| [13] | B.R. McCreadie, M.D. Morris, T.C. Chen, et al., Bone tissue compositional differences in women with and without osteoporotic fracture, Bone 39 (2006) 1190- 1195. |

| [14] | K.A. Esmonde-White, F.W.L. Esmonde-White, C.M. Holmes, M.D. Morris, B.J. Roessler, Alterations to bone mineral composition as an early indication of osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot, Diabetes Care 36 (2013) 3652-3654. |

| [15] | J.D.P. McElderry, G.S. Zhao, A. Khmaladze, et al., Tracking circadian rhythms of bone mineral deposition in murine calvarial organ cultures, J. Bone Miner. Res. 28 (2013) 1846-1854. |

| [16] | J.R. Peterson, P.I. Okagbare, S. De La Rosa, et al., Early detection of burn induced heterotopic ossification using transcutaneous Raman spectroscopy, Bone 54 (2013) 28-34. |

| [17] | J.R. Peterson, S. De La Rosa, H.L. Sun, et al., Burn injury enhances bone formation in heterotopic ossification model, Ann. Surg. 259 (2014) 993-998. |

| [18] | E.M. McNerny, B. Gong, M.D. Morris, D.H. Kohn, Bone fracture toughness and strength correlate with collagen cross-link maturity in a dose-controlled lathyrism mouse model, J. Bone Miner. Res. (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ jbmr.2356. |

| [19] | B. Gong, M.E. Oest, K.A. Mann, T.A. Damron, M.D. Morris, Raman spectroscopy demonstrates prolonged alteration of bone chemical composition following extremity localized irradiation, Bone 57 (2013) 252-258. |

| [20] | C.N. Tchanque-Fossuo, B. Gong, B. Poushanchi, et al., Raman spectroscopy demonstrates Amifostine induced preservation of bone mineralization patterns in the irradiated murine mandible, Bone 52 (2013) 712-717. |

| [21] | P.A. Felice, B. Gong, S. Ahsan, et al., Raman spectroscopy delineates radiationinduced injury and partial rescue by amifostine in bone: a murine mandibular model, J. Bone Miner. Metab. (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00774-014- 0599-1. |

| [22] | H.D. Barth, E.A. Zimmermann, E. Schaible, et al., Characterization of the effects of x-ray irradiation on the hierarchical structure and mechanical properties of human cortical bone, Biomaterials 32 (2011) 8892-8904. |

| [23] | N. Russell, R.A. Oliver, W.R. Walsh, The effect of sterilization methods on the osteoconductivity of allograft bone in a critical-sized bilateral tibial defect model in rabbits, Biomaterials 34 (2013) 8185-8194. |

| [24] | L. Kubisz, M. Polomska, FT NIR Raman studies on gamma-irradiated bone, Spectrochim. Acta. Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 66 (2007) 616-625. |

| [25] | E.R. Bandstra, R.W. Thompson, G.A. Nelson, et al., Musculoskeletal changes in mice from 20-50 cGy of simulated galactic cosmic rays, Radiat. Res. 172 (2009) 21-29. |

| [26] | H. Kondo, N.D. Searby, R. Mojarrab, et al., Total-body irradiation of postpubertal mice with (137) Cs acutely compromises the microarchitecture of cancellous bone and increases osteoclasts, Radiat. Res. 171 (2009) 283-289. |

| [27] | W. Hubner, A. Blume, R. Pushnjakova, Y. Dekhtyar, H.J. Hein, The influence of Xray radiation on the mineral/organic matrix interaction of bone tissue: an FT-IR microscopic investigation, Int. J. Artif. Organs 28 (2005) 66-73. |

| [28] | A.L. Boskey, A.S. Posner, Bone structure, composition, and mineralization, Orthop. Clin. North Am. 15 (1984) 597-612. |

| [29] | E.P. Paschalis, K. Verdelis, S.B. Doty, et al., Spectroscopic characterization of collagen cross-links in bone, J. Bone Miner. Res. 16 (2001) 1821-1828. |

| [30] | M. Raghavan, N.D. Sahar, R.H. Wilson, et al., Quantitative polarized Raman spectroscopy in highly turbid bone tissue, J. Biomed. Opt. 15 (2010) 037001. |

| [31] | G. Falgayrac, S. Facq, G. Leroy, B. Cortet, G. Penel, New method for Raman investigation of the orientation of collagen fibrils and crystallites in the haversian system of bone, Appl. Spectrosc. 64 (2010) 775-780. |

| [32] | M. Kazanci, P. Roschger, E.P. Paschalis, K. Klaushofer, P. Fratzl, Bone osteonal tissues by Raman spectral mapping: orientation-composition, J. Struct. Biol. 156 (2006) 489-496. |

| [33] | R.G. Handschin, W.B. Stern, Crystallographic and chemical analysis of human bone apatite (Crista Iliaca), Clin. Rheumatol. 13 (1994) 75-90. |

| [34] | O. Akkus, F. Adar, M.B. Schaffler, Age-related changes in physicochemical properties of mineral crystals are related to impaired mechanical function of cortical bone, Bone 34 (2004) 443-453. |

| [35] | A. Lyons, N. Ghazali, Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: current understanding of its pathophysiology and treatment, Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 46 (2008) 653-660. |

| [36] | V. Vanderpuye, A. Goldson, Osteoradionecrosis of the mandible, J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 92 (2000) 579-584. |

| [37] | M.L. Hensley, K.L. Hagerty, T. Kewalramani, et al., American society of clinical oncology 2008 clinical practice guideline update: use of chemotherapy and radiation therapy protectants, J. Clin. Oncol. 27 (2009) 127-145. |

| [38] | A. Chandra, S.H. Lan, J. Zhu, et al., PTH prevents the adverse effects of focal radiation on bone architecture in young rats, Bone 55 (2013) 449-457. |

| [39] | T.A. Damron, B. Margulies, D. Biskup, J.A. Spadaro, Amifostine before fractionated irradiation protects bone growth in rats better than fractionation alone, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 50 (2001) 479-483. |

| [40] | C.N. Tchanque-Fossuo, A. Donneys, S.S. Deshpande, et al., Amifostine remediates the degenerative effects of radiation on the mineralization capacity of the murine mandible, Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 129 (2012) 646e-655e. |

| [41] | R.L. Capizzi, Amifostine: the preclinical basis for broad-spectrumselective cytoprotection of normal tissues from cytotoxic therapies, Semin. Oncol. 23 (1996) 2-17. |

| [42] | R.L. Capizzi, Clinical status and optimal use of amifostine, Oncology 13 (1999) 47- 59. |

| [43] | D.M. Brizel, T.H. Wasserman, M. Henke, et al., Phase III randomized trial of amifostine as a radioprotector in head and neck cancer, J. Clin. Oncol. 18 (2000) 3339-3345. |

| [44] | T.H. Wasserman, D.M. Brizel, M. Henke, et al., Influence of intravenous amifostine on xerostomia, tumor control, and survival after radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: 2-year follow-up of a prospective, randomized, phase III trial, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 63 (2005) 985-990. |

| [45] | P.I. Okagbare, F.W. Esmonde-White, S.A. Goldstein, M.D. Morris, Development of non-invasive Raman spectroscopy for in vivo evaluation of bone graft osseointegration in a rat model, Analyst 135 (2010) 3142-3146. |

| [46] | M.V. Schulmerich, J.H. Cole, K.A. Dooley, et al., Noninvasive Raman tomographic imaging of canine bone tissue, J. Biomed. Opt. 13 (2008) 020506. |

| [47] | M.V. Schulmerich, W.F. Finney, R.A. Fredricks, M.D. Morris, Subsurface Raman spectroscopy and mapping using a globally illuminated non-confocal fiber-optic array probe in the presence of Raman photon migration, Appl. Spectrosc. 60 (2006) 109-114. |

| [48] | M.V. Schulmerich, K.A. Dooley, M.D. Morris, et al., Transcutaneous fiber optic Raman spectroscopy of bone using annular illumination and a circular array of collection fibers, J. Biomed. Opt. 11 (2006) 060502. |

| [49] | P.I. Okagbare, M.D. Morris, Polymer-capped fiber-optic Raman probe for noninvasive Raman spectroscopy, Analyst 137 (2012) 77-81. |