In the development of Ni-based catalysts for carbon dioxide reforming of methane (DRM), a major focus is directed on the effective suppression of carbon deposition on catalyst surface during the reaction [1]. Although tremendous attempts have been made, carbon deposition is still a great challenge for Ni-based catalyst, preventing DRM from commercialization. In fact, DRM is a promising way to utilize natural gas and to reduce greenhouse gases [2]. Also, the synthetic gas with a low H2/CO ratio formed in DRM is suitable in the synthesis of valuable long chain hydrocarbons and oxygenated chemicals through the Fischer–Tropsch process [3,4].

It has been pointed out that the origin of carbon deposition during DRM mainly occursvia either methane decomposition (CH4-C(s)+2H2) or carbon monoxide disproportionation (2CO-C(s)+CO2). The former is endothermic and favored at higher temperatures, while the latter is exothermic and favored at lower temperatures[5,7]. Promoter and catalyst particle size are very important in controlling carbon deposition on nickel-based catalysts [1]. Bychkovet al.[8] reported that the rate of carbon accumulation depends on the Ni particle size in the catalyst. Guczi et al.[9] found that the addition of 0.5 wt% Au to 8.8 wt% Ni/MgAl2O4 improved the catalytic activity and decreased the formation of coke. Pt impregnated Ni-MCM-41 also exhibited the high conversion and stability. The effect of Pt was suggested to be due to its low tendency to carbon deposition [10]. For Ni-MCM-41 catalyst, the addition of Pd leads to formation of well dispersed small nickel particles on surface which accounts for the good activity and stability of the catalyst [2].

Wu and Chou [11] studied bimetallic Rh–Ni/BN catalyst, and they found that the addition of Rh increased the activity of dry reforming as well as the stability of the catalysts. Hou and Yashima [12] also found that small amount of Rh–promoted Ni/a-Al2O3 combined the advantages of both Ni and Rh, and exhibited excellent performance for its higher activity and lower cokeformation rate. The present work focuses on the effects of Rh addition on catalyst properties and catalytic performance with an attempt to avoid carbon formation in dry reforming of methane over Rh–Ni bimetallic catalysts. Catalysts with different weight ratio of Rh/Ni are comparatively investigated. In addition, the carbonaceous species formedviaeither CH4 decomposition or CO disproportionation and removed by CO2 oxidation are discussed. 2. Experimental 2.1. Catalyst preparationl

SBA-15 was synthesized according to the literature method [13]. Nickel nitrate and rhodium chloride were dissolved in deionized water to form solution A, in which Ni content (10 wt%) was kept constant while the Rh content was 0, 0.2 and 0.4 wt%, respectively. Solution A with a volume identical to the pore volume of SBA-15 was added dropwise into the dispersion of 20 mL n-hexane containing 0.5 g SBA-15. The mixture was stirred continually for one day. After removal of the solvent by volatilization, the samples were calcined in air from room temperature to 550℃ with a ramp rate of 2℃ min-1 and then calcined for further 6 h at 550℃. The samples prepared were denoted as Ni/SBA-15, 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 and 0.04Rh–Ni/SBA-15, where the value is the weight ratio of Rh/Ni. 2.2. Characterization

Temperature-programmed reduction (TPR) studies were performed on a Micromeritics ChemiSorb 2720 apparatus. TPR profiles were obtained by passing a 10% H2/Ar flow (50 mL min-1) through the samples. Temperature was increased at a rate of 10℃ min-1 from room temperature to 1000℃ and the amount of H2 consumed was determined with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). XRD patterns were recorded on a Bruker D8 Advances X-ray diffractometer using Cu-Ka1 radiation (l= 0.15406 nm) with a voltage of 40 kV and a current of 40 mA. TEM images were obtained from a JEOL JEM2011 microscope operated at 200 kV. In order to obtain statistically reliable information, the size ofca.200 particles from at least 10 representative images for each sample was measured to calculate the average particle size. The amounts of carbon formed on the catalysts were determined by a Perkin– Elmer TGA7/DTA7 thermal analyzer in air with a flow rate of 50 mL minand a heating rate of 10℃ min-1. 2.3. Reforming of CH4with CO2

The dry reforming experiments were conducted at atmospheric pressure in a conventional flow apparatus using a stainless steel fixed bed reactor with quartz lining (i.d. = 5 mm). Typically, 40 mg of the catalyst with 40–60 mesh was reduced in hydrogen at 650℃ for 2 h before reaction. The CO2/CH4reforming was carried out at 650℃ with a gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of 12,000 and 48,000 mL h-1g-1 (CH4:CO2:N2= 1:1:3). The effluent was analyzed using on-line gas chromatography with a TCD. A TDX-01 column was used for the separation of H2, CO, CH4and CO2. 3. Results and discussion

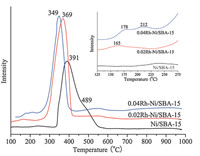

TPR experiments were performed to investigate the reducibility of the Ni/SBA-15 and Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalysts and the interaction between the metal species and the support (Fig. 1). For 0.02Rh–Ni/ SBA-15, the small well defined TPR peak at 165℃ is caused by the reduction of rhodium oxide, implying that there is only one kind of rhodium oxide on SBA-15. However, the reduction temperature is higher than that observed on the supported Rh/SiO2 catalyst at 80℃ [14], indicating that either Rh is better dispersed in bimetallic catalyst than in the monometallic one, or is in strong interaction with nickel [15]. The profile of 0.04Rh–Ni/SBA-15 shows two clear peaks, one at 178℃ and another at 212℃. Both can be attributed to the reduction of Rh, indicating that there are at least two kinds of rhodium oxide species [16]. For all catalysts, one main reduction peak centered at around 340–400℃ is observed. This can be explained by the reduction of supported Ni oxide species in different interaction with the support surface. The Rh free Ni/SBA-15 catalyst shows a strong peak at 391℃ and a shoulder at 489℃. This means an uneven distribution of nickel oxide species interacting differently with the support [17]. The main peak is shifted to 369℃ in 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15, indicating that the reduction of NiO is promoted in the presence of the noble metal. Rhodium oxide precursor, which is easily reduced to Rh 0 at lower temperatures, is able to activate the hydrogen, thus favoring the reduction of nickel oxide species by H2 spill-over at lower temperature[15,18,19]. Meanwhile, the main peak of 0.04Rh– Ni/SBA-15 shifted to an even lower temperature of 349℃ due to a stronger interaction between Rh and Ni. The catalyst promoted with rhodium behaves more reducible than the monometallic Ni catalyst, ascribing to the increase of the interaction between Rh and Ni and higher dispersion of nickel [19]. Damyanovaet al.[2] reported that the catalysts with synergy effect between Pd and Ni provided good metal dispersion and high degree of reduction.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1.TPR profiles of Ni/SBA-15 and Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalysts. | |

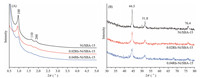

The small-angle XRD patterns of the catalysts are shown in Fig. 2A. Three well-resolved peaks of SBA-15 are indexed as (100), (200) and (210) reflections associated with p6mm hexagonal symmetry. In the large-angle XRD patterns (Fig. 2B), the reduced Ni/SBA-15 and Rh–Ni/SBA-15 samples show reflections at 44.58, 51.88 and 76.48 assigned to Fm3m Ni phases with the lattice constant a of 3.523 A˚ (JCPDS 87-0712). Furthermore, no peak associated with Rh was observed, suggesting that Rh is well dispersed or the content of Rh is too low to be detected by XRD [15, 19, 20].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2.XRD patterns of reduced Ni/SBA-15 and Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalysts. (A) Small-angle XRD in the range of 0.5–5.08and (B) large-angle XRD in the range of 30–808 | |

Fig. 3 shows the TEM images of the reduced Ni/SBA-15 and Rh– Ni/SBA-15 samples. Ni particle sizes of average 6.5, 6.2 and 6.1 nm can be observed on the reduced Ni/SBA-15, 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 and 0.04Rh–Ni/SBA-15 with narrow size distribution, respectively, which are smaller than the pore size of SBA-15 of 6.6 nm. It can be concluded that the presence of Rh in Ni catalysts leads to a decrease of the Ni particle size. Besides, it is to be noted that large Ni particles with an average particle size of 22.4, 17.2 and 16.9 nm were also observed by TEM on the reduced Ni/SBA-15, 0.02Rh–Ni/ SBA-15 and 0.04Rh–Ni/SBA-15, respectively. These Ni particles were located on the external surface of the SBA-15 framework, which could not be confined within the pore channels of mesoporous support.

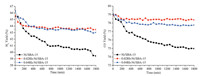

The initial catalytic activity of the catalysts for the DRM reaction at 650℃ with GHSV of 48,000 mL h-1g-1 was studied. For Ni/SBA-15, the yields of H2 and CO were 49% and 67%, respectively. Meanwhile, the yields of H2and CO were increased to 58% and 73% over 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15. Addition of small amount of Rh to monometallic Ni catalyst leads to an increase of the initial activity. The yields of H2and CO as a function of the time on stream for the first 30 h are presented in Fig. 4. The apparent deactivation was clearly observed over the monometallic Ni catalyst. During the 30 h time-on-stream, the yields of H2 and CO over Ni/SBA-15 catalyst dropped from 66% to 60% and from 79% to 75%, respectively. For 0.04Rh–Ni/SBA-15, the yield of H2 decreased from 66% to 63% while the yield of CO decreased from 79% to 78% within 30 h. It is important to point out that the Rh promoted 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalyst is quite stable for DRM reaction. After 30 h reaction the yield of CO was nearly the same whereas the yield of H2 was only about 2% lower than that at beginning of the reaction. It can be observed that even adding small amount of Rh the stability of bimetallic Rh–Ni catalyst for the DRM is considerably improved with respect to the monometallic Ni catalyst.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3.TEM images of (A) Ni/SBA-15, (B) 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 and (C) 0.04Rh–Ni/SBA-15. Ni particle size distributions of (D) Ni/SBA-15, (E) 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15and (F) 0.04Rh– Ni/SBA-15. Catalysts were reduced with H2at 650℃ for 2 h. | |

The carbonaceous deposits on the used Ni/SBA-15 and Rh–Ni/

SBA-15 catalysts after stability test were investigated by TG/DTA under

oxidative atmosphere (not shown). The total amount of deposited

carbon over the used catalysts increases in the following sequence:

0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 (14.7%)<0.04Rh–Ni/SBA-15 (20.7%)

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4Long-term stability test over Ni/SBA-15 and Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalysts. Reaction conditions: CH4:CO2:N2= 1:1:3, GHSV = 12,000 mL h-1g-1, 650 ℃, 1 atm. | |

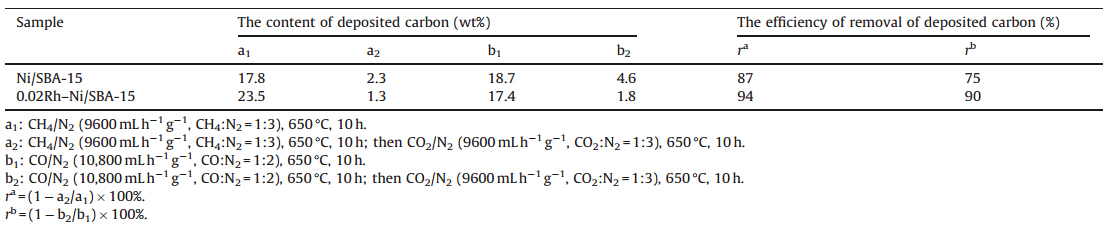

It has been proved that both CH4 and CO contribute to the accumulation of deposited carbon [23, 24]. To explain the role of Rh on the suppression of carbon formation, other experiments have been performed. Ni/SBA-15 and 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalyst were first exposed to the flow of methane or carbon monoxide at 650℃ for 10 h, then switched to the flow of CO2at the identical condition. The amounts of carbon deposition over both Ni/SBA-15 and 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 after the reaction were investigated by means of TG as shown in Table 1. After being exposed in the flow of methane, the content of carbon deposition can be estimated as 17.8 wt% and 23.5 wt% for Ni/SBA-15 and 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalyst, respectively. This is due to the high efficiency of methane decomposition over 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 than that over Ni/SBA-15. It has been reported that the rate of methane activation increased along with the Ni dispersion [12], suggesting that more active sites for CH4 dissociation can be obtained by decreasing the metal particle size [25]. XRD, TEM and TPR results indicate that when Rh is added into the Ni catalyst, a synergic effect is created between Rh and Ni, which is capable of decreasing the Ni particle size and increasing the dispersion. After further treatment with CO2, the residual carbon was 2.3 wt% and 1.3 wt% for Ni/SBA-15 and 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalyst, indicative of the enhancing removal of carbon over 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 (94%), compared to Ni/SBA-15 (87%).

| Table 1 TG data of Ni/SBA-15 and 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalysts. |

The amount of carbon deposited on Ni/SBA-15 and 0.02Rh–Ni/ SBA-15 catalyst after exposure in the flow of carbon monoxide was 18.7 wt% and 17.4 wt%, respectively, in accordance with the observation reported by Goulaet al. [25] that the amount of carbon derived from CO disproportionation was larger on the catalyst with the bigger nickel particle size. After further treatment with CO2, the residual carbon was 4.6 wt% and 1.8 wt% for Ni/SBA-15 and 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalyst, respectively, corresponding to the efficiencies of removal of deposited carbon of 75% and 90%. It is clear that Rh–Ni species activates CO2 and releases active oxygen atom for removal of deposited carbon and, in particular, the 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalyst shows higher efficiency than Ni/SBA-15 catalyst (Table 1). It was reported [2] that the small particle size can accelerate the activation of CO2. Comparing the Ni metal particle size of reduced Ni/SBA-15 and 0.02Rh–Ni/SBA-15 catalyst it may be concluded that the small metal particle size for bimetallic catalyst enhances the activation of the CO2dissociation, which leads to the low carbon deposition in the DRM reaction. 4. Conclusion

The effect of Rh on Ni/SBA-15 catalyst was investigated for carbon dioxide reforming of methane. Comparative studies between supported monometallic Ni and bimetallic Rh–Ni catalyst show that the high catalytic performance of Rh promoted Ni catalysts arises from the interaction between Ni and Rh in the bimetallic system, which provides higher metal dispersion and improves reducibility of Ni and coke resistance.' Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21173050, 21371035).

| [1] | A. Shamsi, Carbon formation on Ni-MgO catalyst during reaction of methane in the presence of CO2 and CO, Appl. Catal. A Gen. 277 (2004) 23-30. |

| [2] | S. Damyanova, B. Pawelec, K. Arishtirova, et al., MCM-41 supported PdNi catalysts for dry reforming of methane, Appl. Catal. B Environ. 92 (2009) 250-261. |

| [3] | M.L. Zhang, S.F. Ji, L.H. Hu, et al., Structural characterization of highly stable Ni/SBA-15 catalyst and its catalytic performance for methane reforming with CO2, Chin. J. Catal. 27 (2006) 777-782. |

| [4] | C.K. Shi, P. Zhang, Effect of a second metal (Y, K, Ca, Mn or Cu) addition on the carbon dioxide reforming of methane over nanostructured palladium catalysts, Appl. Catal. B Environ. 115 (2012) 190-200. |

| [5] | M.C.J. Bradford, M.A. Vannice, CO2 reforming of CH4, Catal. Rev. Sci. Eng. 41 (1999) 1-42. |

| [6] | M.C.J. Bradford, M.A. Vannice, Catalytic reforming of methane with carbon dioxide over nickel catalysts. 1. Catalyst characterization and activity, Appl. Catal. A Gen. 142 (1996) 73-96. |

| [7] | L. Qian, Z.F. Yan, Study on the reaction mechanism for carbon dioxide reforming of methane over supported nickel catalyst, Chin. Chem. Lett. 14 (2003) 1081-1084. |

| [8] | V.Y. Bychkov, Y.P. Tyulenin, A.A. Firsova, et al., Carbonization of nickel catalysts and its effect on methane dry reforming, Appl. Catal. A Gen. 453 (2013) 71-79. |

| [9] | L. Guczi, G. Stefler, O. Geszti, et al., Methane dry reforming with CO2: a study on surface carbon species, Appl. Catal. A Gen. 375 (2010) 236-246. |

| [10] | D.P. Liu, W.N.E. Cheo, Y.W.Y. Lim, et al., A comparative study on catalyst deactivation of nickel and cobalt incorporated MCM-41 catalysts modified by platinum in methane reforming with carbon dioxide, Catal. Today 154 (2010) 229-236. |

| [11] | J.C.S. Wu, H.C. Chou, Bimetallic Rh-Ni/BN catalyst for methane reforming with CO2, Chem. Eng. J. 148 (2009) 539-545. |

| [12] | Z.Y. Hou, T. Yashima, Small amounts of Rh-promoted Ni catalysts for methane reforming with CO2, Catal. Lett. 89 (2003) 193-197. |

| [13] | D.Y. Zhao, J.L. Feng, Q.S. Huo, et al., Triblock copolymer syntheses of mesoporous silica with periodic 50-300 angstrom pores, Science 279 (1998) 548-552. |

| [14] | W.Z. Weng, C.R. Luo, J.J. Huang, Y.Y. Liao, H.L. Wan, Comparative study on the mechanisms of partial oxidation of methane to syngas over rhodium supported on SiO2 and γ-Al2O3, Top. Catal. 22 (2003) 87-93. |

| [15] | A. Le Valant, N. Bion, F. Can, D. Duprez, F. Epron, Preparation and characterization of bimetallic Rh-Ni/Y2O3-Al2O3 for hydrogen production by raw bioethanol steam reforming: influence of the addition of nickel on the catalyst performances and stability, Appl. Catal. B Environ. 97 (2010) 72-81. |

| [16] | S. Gaur, D.J. Haynes, J.J. Spivey, Rh, Ni, and Ca substituted pyrochlore catalysts for dry reforming of methane, Appl. Catal. A Gen. 403 (2011) 142-151. |

| [17] | V.L. Barrio, P.L. Arias, J.F. Cambra, et al., Aromatics hydrogenation on silicaalumina supported palladium-nickel catalysts, Appl. Catal. A Gen. 242 (2003) 17-30. |

| [18] | M. Ocsachoque, F. Pompeo, G. Gonzalez, Rh-Ni/CeO2-Al2O3 catalysts for methane dry reforming, Catal. Today 172 (2011) 226-231. |

| [19] | M. Garcia-Dieguez, I.S. Pieta, M.C. Herrera, M.A. Larrubia, L.J. Alemany, Rh-Ni nanocatalysts for the CO2 and CO2 + H2O reforming of methane, Catal. Today 172 (2011) 136-142. |

| [20] | H. Anita, G. Stefler, O. Geszti, et al., Methane dry reforming with CO2 on CeZr-oxide supported Ni, NiRh and NiCo catalysts prepared by sol-gel technique: relationship between activity and coke formation, Catal. Today 169 (2011) 102-111. |

| [21] | U. Oemar, K. Hidajat, S. Kawi, Role of catalyst support over PdO-NiO catalysts on catalyst activity and stability for oxy-CO2 reforming of methane, Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 402 (2011) 176-187. |

| [22] | I. Luisetto, S. Tuti, E. Di Bartolomeo, Co, Ni supported on CeO2 as selective bimetallic catalyst for dry reforming of methane, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37 (2012) 15992-15999. |

| [23] | J.Z. Luo, Z.L. Yu, C.F. Ng, C.T. Au, CO2/CH4 reforming over Ni-La2O3/5A: an investigation on carbon deposition and reaction steps, J. Catal. 194 (2000) 198-210. |

| [24] | N.A. Pechimuthu, K.K. Pant, S.C. Dhingra, Deactivation studies over Ni-K/CeO2- Al2O3 catalyst for dry reforming of methane, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 46 (2007) 1731- 1736. |

| [25] | M.A. Goula, A.A. Lemonidou, A.M. Efstathiou, Characterization of carbonaceous species formed during reforming of CH4 with CO2 over Ni/CaO-Al2O3 catalysts studied by various transient techniques, J. Catal. 161 (1996) 626-640. |