b Tianjin Key Laboratory on Technologies Enabling Development of Clinical Therapeutics and Diagnostics, School of Pharmacy, Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin 300060, China

In recent years, supramolecular, one-dimensional (1D) nanostructures composed of electronically active constituents have stimulated increasing interest in the emerging fields of nanotechnology, mainly due to their promising applications in the construction of electronic and optoelectronic nanodevices [1]. In this regard, fibrous self-assembly by non-covalent interactions is a frequently observed feature in our biological and physiological events, and consequently, considerable effort has been devoted to mimicking the highly ordered fibrous morphologies with supramolecular characterization [2]. Particularly, in the numerous components that are available for the formation of 1D nanoarchitectures, perylene bisimide and its analogs are intensively studied as a photofunctional dye and n-type organic semiconductor with unique photo- and electroactive properties. A variety of multichromophoric assemblies based on perylene bisimide building blocks have been widely fabricated through covalent or non-covalent strategies [3]. For instance, Liu et al. have reported new types of fluorescence sensory material using perylene as the probing signal and cyclodextrin cavity as the receptor unit, implementing an effective, reversible and selective solid state sensor for volatile aniline vapor [4]. Li and his co-workers have utilized p-phenylenevinylenelinked perylene diimides to construct the solvent-dependent molecular aggregates of nanospheres and vesicles, in which the fluorescence intensities were greatly enhanced upon laser irradiation [5].

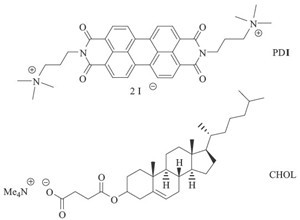

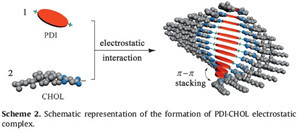

Moreover, among all the non-covalent driving forces, the primary electrostatic attraction is considered as a reliable and flexible method to construct various supramolecular materials, by which some secondary interactions, such as hydrophobic, π-π stacking, van der Waals, and hydrogen bonding interactions, could be further stimulated to propagate the eventual formation of superstructures [6]. Therefore, inspired by this fascinating principle, we present herein the design and construction of 1D nanowires through the spontaneous self-assembly of cationic perylene derivative (Scheme 1, defined as PDI) and anionic cholesterol derivative (Scheme 1, defined as CHOL), taking both the amphiphilicity of cholesterol side chain and the highly affinitive π-π stacking of perylene cores into account. The spectroscopic and microscopic results jointly confirm that the formation of interior structures in PDI⋅CHOL assembly is driven by the strong π-π interaction between two adjacent rigid PDI units, whereas the amphiphilic moieties of CHOL are connected through the electrostatic attraction with PDI and interlace with each other via the side chains.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1.Structural illustration of cationic perylene diimide (PDI) and anionic cholesterol (CHOL) derivatives. | |

All chemicals were commercially available unless noted otherwise. NMR data were recorded on Bruker AV400 spectrometer. UV/vis spectra were recorded in a quartz cell (light path 10 mm) on a Shimadzu UV-3600 spectrophotometer equipped with a PTC-348WI temperature controller. Fluorescence spectra and quantum yields were recorded in a conventional quartz cell (10 mm × 10 mm × 45 mm) at 25 ℃ on a spectrometer employing the single photon counting technique. SEM images were recorded on a HITACHI S-3500N scanning electron microscope.

AFM Measurements: A 1.0 × 10-5 mol/L of sample solution was dropped onto newly clipped mica and then dried in air. The samples were performed by using a Multimode Nanoscope-IIIa scanning probe microscope (Digital Instruments Co., Ltd.) in the tapping mode in air at room temperature.

The molecular structures of PDI and CHOL are shown in Scheme 1. PDI was synthesized by the condensation reaction with perylene tetracarboxylic bisanhydride [7]. Then, CHOL was modified with carboxylic groups to endow the cholesterol backbone with amphiphilicity [8]. It is expected that the combination of cationic PDI with anionic CHOL could confer suprastructural characteristics upon the mutual electrostatic attraction. Moreover, due to the broad optical transparency of the CHOL skeleton in the UV/vis region, the photophysical properties of the PDI⋅CHOL complex can be conveniently monitored by the spectral changes of PDI, as described below.

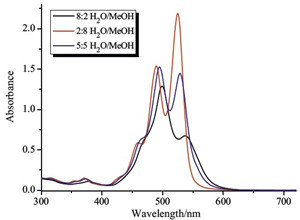

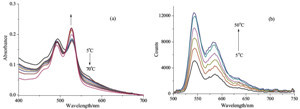

It is well established that the π-π stacking of PDI is critically solvent-dependent [9]. Therefore, we primarily studied the aggregation behaviors of PDI in MeOH/H2O mixed solvents of various compositions. As shown in Fig. 1, the UV/vis spectra of PDI in organic solvents show three clear absorption bands in the range from 400 nm to 600 nm with the maximal absorptivity of the first band around 525 nm, which could be assigned to the typical nonaggregated or low-aggregated state of PDI2+. Comparatively, the spectrum of PDI dramatically decreases as the proportion of water increases, with the maximal absorptivity of the second band around 500 nm, indicative of the pronounced π-π stacking aggregation of PDI moieties in aqueous media. Therefore, considering the aggregation ability of PDI and the water solubility of CHOL, a 1:1 ratio of MeOH/H2O was established as the optimal solvent system for the following studies of the photophysical behavior of the PDI⋅CHOL complex.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1.UV/vis spectra of PDI (5.0 × 10-5 mol/L) in different rations of solvents at 25 ℃. | |

|

Download:

|

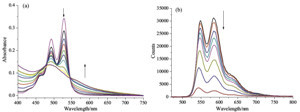

| Fig. 2.UV/vis spectral (a) and fluorescence spectral (b) changes of PDI upon addition of CHOL from 0 to 1 × 10-4 mol/L in 1:1 MeOH/H2O ([PDI] = 1 × 10-5 mol/L) at 25 ℃. | |

|

Download:

|

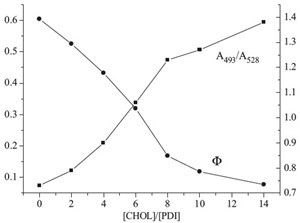

| Fig. 3.Quantum yield and corresponding absorbance changes at 493 nm and 528 nm of PDI⋅CHOL complex with different composition ratios ([PDI] = 1.0 × 10-5 mol/L). | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4.Temperature-dependent UV/vis spectral (a) and fluorescence spectral (b) changes of PDI⋅CHOL complex upon increasing the temperature in 1:1 MeOH/H2O ([PDI] = 1.0 × 10-5 mol/L and [CHOL] = 4.0 × 10-5 mol/L. | |

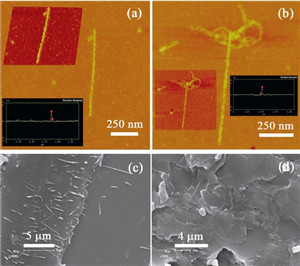

The direct morphological information of helical nanostructures based on the electrostatic complex of PDI with CHOL was further provided by the atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in the tappingmode AFM images of PDI⋅CHOL, a 1D linear morphology can be found when mixing PDI and CHOL at 1:2molar ratio. The height of helical aggregates was about 2.4 nmwith the length up to 500 nm, indicating the existence of thick columnar stacking complex PDI⋅CHOL (Fig. 5a and b). A comparison of the SEM images revealed that the complex of PDI⋅CHOL was structurally distinct from the individual component. That is, the aggregate gave a number of fine linear structures with lengths in more than 2 μm (Fig. 5c), whereas PDI alone was characterized as a regular platelike morphology (Fig. 5d). These results demonstrate that the cholesterol chains play an essential role in this self-organization process [10]. Based on these microscopic results, one can imagine that the strong face-to-face π-π stacking interaction in the perylene moieties could induce the formation of linear assembly of PDI⋅CHOL, inwhich a 1D aligned PDI columnis properly twisted by the tethered cholesterol groups. The proposed aggregation mode is illustrated in Scheme 2.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5.Typical AFM images (a, b) of PDI⋅CHOL complex and SEM images of (c) PDI⋅CHOL complex and (d) PDI prepared in the 1:1 MeOH/H2O mixed solvent ([PDI] = 1.0 × 10-5 mol/L and [CHOL] = 2.0 × 10-5 mol/L). | |

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2.Schematic representation of the formation of PDI⋅CHOL electrostatic complex. | |

In conclusion, the electrostatic interaction between positively charged PDI and negatively charged CHOL is comprehensively studied, definitely giving the stable supramolecular nanofibers in the solid state. Moreover, as investigated by spectroscopic titrations, it is established that the photophysical behaviors in the supramolecular complex of PDI⋅CHOL could be efficiently modulated by the changes of temperature and solvent polarity. We also envisage that the PDI/CHOL coupling, as an operating strategy for fibrous assemblies, may find potential applications in the construction of new supramolecular, functional nanodevices.

This work was financially supported by the National Key Subject of Drug Innovation (No. 2013ZX09402-202) and the Key Projects in the Tianjin Science & Technology Pillar Program (No. 12ZCZDSY01200).

| [1] | (a) Z. Schnepp, Biopolymers as a flexible resource for nanochemistry, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52 (2013) 1096-1108; (b) B. Nikoobakht, X. Wang, A. Herzing, J. Shi, Scalable synthesis and device integration of self-registered one-dimensional zinc oxide nanostructures and related materials, Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2013) 342-365; (c) R.S. Devan, R.A. Patil, J.H. Lin, Y.R. Ma, One-dimensional metal-oxide nanostructures: recent developments in synthesis, characterization, and applications, Adv. Funct. Mater. 22 (2012) 3326-3370; (d) J.W. Liu, H.W. Liang, S.H. Yu, Macroscopic-scale assembled nanowire thin films and their functionalities, Chem. Rev. 112 (2012) 4770-4799; (e) Z.G. Tao, T.G. Zhan, T.Y. Zhou, X. Zhao, Z.T. Li, Synthesis, properties, and selfassembly of 2,3-bis(n-octyl)hexaazatriphenylene, Chin. Chem. Lett. 24 (2013) 453-456. |

| [2] | (a) Z. Zhang, J. Hu, P.X. Ma, Nanofiber-based delivery of bioactive agents and stem cells to bone sites, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 64 (2012) 1129-1141; (b) V. Leung, F. Ko, Biomedical applications of nanofibers, Polym. Adv. Technol. 22 (2011) 350-365; (c) C.A.E. Hauser, S. Zhang, Designer self-assembling peptide nanofiber biological materials, Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 (2010) 2780-2790; (d) Y.Y. Li, W.J. Zhao, H.C. Zhang, et al., Triple-transforming gel prepared by β-cyclodextrin, diphenylamine and lithium chloride in N,N-dimethylacetamide, Chin. Chem. Lett. 21 (2010) 1251-1254. |

| [3] | (a) E. Kozma, M. Catellani, Perylene diimides based materials for organic solar cells, Dyes Pigments 98 (2013) 160-179; (b) C. Shao, M. Grüne, M. Stolte, F.Würthner, Perylene bisimide dimer aggregates: fundamental insights into self-assembly by NMR and UV/vis spectroscopy, Chem. Eur. J. 18 (2012) 13665-13677; (c) D. Görl, X. Zhang, F. Würthner, Molecular assemblies of perylene bisimide dyes in water, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (2012) 6328-6348; (d) T.F.A. De Greef, M.M.J. Smulders, M. Wolffs, et al., Supramolecular polymerization, Chem. Rev. 109 (2009) 5687-5754; (e) L. Zang, Y. Che, J.S. Moore, One-dimensional self-assembly of planar π-conjugated molecules: adaptable building blocks for organic nanodevices, Acc. Chem. Res. 41 (2008) 1596-1608. |

| [4] | B.P. Jiang, D.S. Guo, Y. Liu, Self-assembly of amphiphilic perylene-cyclodextrin conjugate and vapor sensing for organic amines, J. Org. Chem. 75 (2010) 7258-7264. |

| [5] | Y. Yu, Q. Shi, Y. Li, et al., Solid supramolecular architecture of a perylene diimide derivative for fluorescent enhancement, Chem. Asian J. 7 (2012) 2904-2911. |

| [6] | (a) L. Wang, L.L. Li, H.L. Ma, H. Wang, Recent advances in biocompatible supramolecular assemblies for biomolecular detection and delivery, Chin. Chem. Lett. 24 (2013) 351-358; (b) D.A. Dougherty, The cation π interaction, Acc. Chem. Res. 46 (2013) 885-893; (c) K.D. Daze, F. Hof, The cation-π interaction at protein-protein interaction interfaces: developing and learning from synthetic mimics of proteins that bind methylated lysines, Acc. Chem. Res. 46 (2013) 937-945; (d) J.A. Subirana, M. Soler-Lopez, Cations as hydrogen bond donors: a view of electrostatic interactions in DNA, Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32 (2003) 27-45; (e) P. Ghosh, G. Federwisch, M. Kogej, et al., Controlling the rate of shuttling motions in [2]rotaxanes by electrostatic interactions: a cation as solvent-tunable brake, Org. Biomol. Chem. 3 (2005) 2691-2700. |

| [7] | T. Ma, C. Li, G.Q. Shi, Optically active supramolecular complex formed by ionic self-assembly of cationic perylenediimide derivative and adenosine triphosphate, Langmuir 24 (2008) 43-48. |

| [8] | C.H. Zhang, D. Liu, B.L. Zhou, J.P. Deng, W.T. Yang, Poly(N-propargylamide)s bearing cholesteryl moieties: preparation and optical activity, Reactive Functional Polym. 72 (2012) 832-838. |

| [9] | F. Würthner, Perylene bisimide dyes as versatile building blocks for functional supramolecular architectures, Chem. Commun. (2004) 1564-1579. |

| [10] | (a) J. Yan, J. Liu, Y. Sun, et al., Oligo(FcDC-co-CholDEA) with ferrocene in the main chain and cholesterol as a pendant group -preparation and unusual properties, J. Phys. Chem. B 114 (2010) 13116-13120; (b) C.J. Chen, J.C. Wang, E.Y. Zhao, et al., Self-assembly cationic nanoparticles based on cholesterol-grafted bioreducible poly(amidoamine) for siRNA delivery, Biomaterials 34 (2013) 5303-5316. |