b College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China;

c National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing 102206, China

1. Introduction

Despite the well-known weaknesses,structure-based virtual screening (molecular docking) is now one of the most practical techniques to leverage target structure for ligand discovery [1, 2, 3]. Molecular docking approach is designed to identify small molecules from a large chemical library for shape and physicochemical complementarity to a macromolecular binding site. Numerous studies have applied such an approach to identify novel ligands for various drug targets [4]. The two major challenges in molecular docking are sampling (i.e.,enumerating possible conformations of ligands in the receptor binding pocket) and scoring (i.e. ,identifying the correct binding orientation and conformation out of an enormous number of alternative modes for each ligand,and ranking different ligands with respect to their estimated binding affinity) [5]. Nevertheless,in order to dock a large compound library,a scoring function has to be simple,fast, and derived from a physically reasonable equation.

Physics-based scoring methods model the protein-ligand interactions based on the law of physics,and have the advantage to be more accurate with systematic improvements [6]. During the past few years,we have developed a hierarchical physics-based virtual screening protocol to integrate different computational methods in an increasing order of complexity and more physically realistic manner,in which a rapid-to-compute docking program (DOCK3.5.54) is used to screen large compound databases,and a more physically rigorous approach (MM-GB/SA) is applied to refine and rescore docking poses [7, 8]. However,one major limitation of this protocol is that it relies entirely on the docking algorithm to identify the correct binding pose,and is not effective in rescuing grossly mis-docked ligands. Therefore,we could envision a simple extension by subjecting a small number of dissimilar binding poses for each ligand to the more accurate MM-GB/SA rescoring (arguably more computationally expensive),and use the most favorable binding energy for rank-ordering ligands.

To obtain dissimilar docking poses during docking,an efficient yet effective pose clustering algorithm is essential to process the millions of docking poses on-the-fly. Several clustering algorithms are available,including seeded RMSD (root-mean-square deviation) clustering,greedy RMSD clustering,K-means clustering, Jarvis-Patrick clustering and top-first clustering [9, 10]. These methods require at least one pre-assigned cutoff value to determine whether two poses belong to the same structural class, which significantly influences the clustering results. In contrast, KGS-penalty function clustering is cutoff-free [11],particularly efficient in clustering diverse poses in global space in an unbiased manner.

In addition,we can also envision a different strategy to integrate docking methods and informatics (e.g. ,structural analysis) to improve the overall pose prediction performance. The successful identification of near-native poses from decoy poses is challenging for docking scoring function [8]. Therefore,a simpleyet effective way to improve the docking performance is to exclude unreasonable docking poses forbidden by the essential structural criteria [7, 12, 13],such as the number of hydrogen bonds,the number of buried carbon atoms and hydrophobic contact [14, 15].

Here we developed a novel strategy (Fig. 1) to improve molecular docking performance via filtering and clustering without significantly sacrificing the calculation speed. We implemented structural descriptor-based filtering and KGS-penalty function clustering in the DOCK3.5.54 program. The docking output is a small subset of dissimilar docking poses satisfying the essential structural criteria,which makes the more rigorous rescoring processes practically feasible. We assessed our approach against 150 high-quality protein-ligand complex structures. The success rate of predicting near-native binding pose was substantially increased from 53% of the targets to 78%.

|

Download:

|

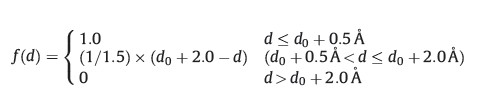

| Fig. 1.The scheme of docking process implemented with pose filtering and clustering,and the mathematic equations applied in clustering algorithm. | |

2. Experimental

Benchmark set preparation: To assess our methodology development, we chose 150 unique protein structures bound with druglike ligands from CSAR-NRC HiQ data set,where protonation state, tautomeric form and hydrogen atom orientation of the ligands and binding site residues were corrected manually [16].

Molecular docking procedure: The automatic docking procedure was described previously [17]. Briefly,each protein was prepared for docking in the same manner (except for several metalloenzymes), and each ligand was docked back into its corresponding binding pocket. An in-house modified version of program DOCK 3.5.54 was used to dock compounds into the protein binding site. The pre-computed conformational ensemble of each ligand [18] was matched against the docking spheres derived from both the receptor and the crystallographic ligand. The grid-based docking energy components,including van der Waals interactions, electrostatic energy and ligand partial desolvation penalty,were calculated and summed up. The ligand docking poses were scored and ranked based on the total docking energy.

Filtering algorithm: The generated docking poses were filtered based on the three types of structural descriptors calculated for each docking pose,including the number of hydrogen bonds,the number of buried carbon atoms and hydrophobic contact. The buried carbon atom is assigned if the distance between the ligand carbon atom and any heavy atom in the receptor is shorter than 4.0A˚ . The hydrophobic contact is defined as follow:

For each ligand,the unreasonable docking poses are automatically removed if the calculated values of any type of descriptors are below the averaged values throughout the entire conformational ensemble,individually.

Clustering algorithm: The docking poses survived from the filtering step were clustered based on KGS-penalty function [11]. The clustering is an iterated process (Fig. 1). In each step,the distance of every two clusters (A and B) is calculated using equation I and the nearest clusters are merged together. For example,i is the element in A and there are I elements in A. Next, the spread of the cluster and the average spread of clusters in this step are calculated using equation II and III. In n step,there are clustnumn clusters. Finally,all the data (T) are grouped to a single cluster. The penalty function is defined based on the normalized spread of clusters and the number of clusters (clustnumn) in each step using equations IV and V. The step with the minimum penalty function is regarded as the step with optimal cluster sets. 3. Results and discussion

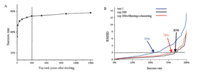

Control calculation: The docking pose accuracy was assessed based on the RMSD values between the coordinates of the heavy atoms in the ligands in the top scoring poses and those in native crystallographic pose,and a cutoff value of 2A˚ was chosen to discriminate the docking success from failure. We firstly computed the RMSD values of the top 1500 docking poses for each ligand,and we plotted the success rates of predicting near-native binding pose (% of the targets with the best RMSD values <2 A˚ ) as the function of the number of top scoring poses (Fig. 2A). Clearly,the success rate reaches 83% at the top 300 ranking poses,and does not increase significantly afterwards by adding more docking poses. Therefore, we chose the top 300 ranking poses as the pool of positive control for the following filtering and clustering steps. In addition,the top 1 ranking pose,as we expected,performs relatively poorly with a success rate of 53% (Fig. 2B),and thus was chosen as the negative control.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2.The comparison of pose prediction accuracy using different strategies. (A) Success rate as the function of the number of top ranking poses. The Y-axis is the percentage of targets with RMSD less than 2A˚ . (B) Comparison of top 1 scoring pose (top 1),top 300 scoring poses (top 300) and top 300 scoring poses after filtering and clustering (top 300 + filtering + clustering). | |

Pose filtering and clustering: We filtered the top 300 ranking poses using the criteria as mentioned above. To ensure adequate numbers of docking poses submitted for clustering,we automatically augmented the extra top ranking poses in the cases that the survived poses are too fewer. Encouragingly,the average number of docking poses was reduced from 300 to 63 after the filtering procedure,while the near-native poses remained. In this step,we did not solely rely on the docking energy scores to select the binding poses. Instead,we used structural filtering strategy to reduce the size of ligand conformational ensemble by satisfying the pre-defined structural filters,which is capable of discriminating the near-native poses from decoy poses effectively.

Next,the remaining poses were submitted for KGS-penalty function-based clustering. Importantly,the average number of docking poses was further reduced to 13,while still maintained the high success rate of 78% (Fig. 2B). Therefore,we successfully found a small number of dissimilar binding poses satisfying the essential binding characteristics without reducing the accuracy of docking pose prediction. We carefully checked the poses resulted from our filtering and clustering method in comparison with the top 13 docking poses. Clearly,our filtering and clustering method produces more diverse binding poses,which may minimize the bias toward the wrongly docked poses due to the simple docking scoring function. For example,the top 13 docking poses all deviate significantly from the native pose (RMSDs >8.3A˚ ) of the ligand in structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in hepatitis Cvirus. In striking contrast,filtering and clustering method enriches the native-like pose with an RMSD of 0.6A˚ (Fig. 3A). The similar result is also observed in several other targets like CprK (Fig. 3B). Our MM-GB/SA refinement and rescoring procedure was not designed for rescuing docking poses deviated significantly from the native pose,we expect that the resulted small number of diverse docking poses (herein 13) with little bias will improve the prediction power of our rescoring procedure. We have previously demonstrated that in this RMSD range (<2 A˚ ),the minimization performed by the MM-GB/SA rescoring method is capable of locally refining the docking geometries,and the minimized energy is effective at improving binding affinity prediction [19].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3.Two case studies on pose prediction accuracy using different strategies. (A) Hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PDB ID: 2D3Z); (B) CprK (PDB ID: 2H6B).Protein is shown in surface and ligands are shown in stick colored by heteroatom. Pose 1 is the best-RMSD pose in the top 300 docking poses after filtering and clustering. Pose 2 is the best-RMSD pose in the top 13 docking pose. Molecular graphics s were made using UCSF Chimera [20]. | |

Successfully identifying the correct binding pose out of an enormous number of alternative modes is still challenging in molecular docking. Especially,our developed hierarchical virtual screening protocol relies on the initial docking algorithm to generate the near-native binding pose,and thus largely limits its usage in practical applications. To overcome this barrier,we implemented the structural descriptor-based filtering and KGSpenalty function-based conformational clustering in docking. In our benchmarking data set containing 150 high-quality protein- ligand complex structures,the success rate of predicting nearnative binding pose increased from 53% of the targets to 78%. We also demonstrated that our approach is particularly robust in rescuing the near-native binding poses with unfavorable docking energy scores in several case studies. Our filtering and clustering strategy can be easily implemented into any docking program and is generally applicable in post-processing docking solutions.

| [1] | X. Barril, R.E. Hubbard, S.D. Morley, Virtual screening in structure-based drug discovery, Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 4 (2004) 779-791. |

| [2] | H. Xu, Z. Jin, S. Liu, et al., Design, synthesis characterization and in vitro biological activity of a series of 3-aryl-6-(bromoarylmethyl)-7H-thiazolo[3,2-b]-1, 2, 4-triazin-7-one derivatives as the novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, Chin. Chem. Lett. 23 (2012) 765-768. |

| [3] | F. Zeng, S. Peng, L. Li, et al., HAT off: structure-based identification of druglike inhibitors of p300 histone acetyltransferase, Acta Pharm. Sin. 48 (2013) 700-708. |

| [4] | X.H. Ma, F. Zhu, X. Liu, et al., Virtual screening methods as tools for drug lead discovery from large chemical libraries, Curr. Med. Chem. 19 (2012) 5562-5571. |

| [5] | B.K. Shoichet, Virtual screening of chemical libraries, Nature 432 (2004) 862-865. |

| [6] | N. Huang, C. Kalyanaraman, K. Bernacki, M.P. Jacobson, Molecular mechanics methods for predicting protein-ligand binding, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8 (2006) 5166-5177. |

| [7] | R. Cao, M. Liu, M. Yin, et al., Discovery of novel tubulin inhibitors via structurebased hierarchical virtual screening, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52 (2012) 2730-2740. |

| [8] | N. Huang, C. Kalyanaraman, J.J. Irwin, M.P. Jacobson, Physics-based scoring of protein-ligand complexes: enrichment of known inhibitors in large-scale virtual screening, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 46 (2006) 243-253. |

| [9] | M.G. Lerner, K.L. Meagher, H.A. Carlson, Automated clustering of probe molecules from solvent mapping of protein surfaces: new algorithms applied to hot-spot mapping and structure-based drug design, J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 22 (2008) 727-736. |

| [10] | D.M. Lorber, B.K. Shoichet, Hierarchical docking of databases of multiple ligand conformations, Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 5 (2005) 739-749. |

| [11] | L.A. Kelley, S.P. Gardner, M.J. Sutcliffe, An automated approach for clustering an ensemble of NMR-derived protein structures into conformationally related subfamilies, Protein Eng. 9 (1996) 1063-1065. |

| [12] | J.H. Hsieh, S. Yin, S. Liu, et al., Combined application of cheminformatics-and physical force field-based scoring functions improves binding affinity prediction for CSAR data sets, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51 (2011) 2027-2035. |

| [13] | J.H. Hsieh, S. Yin, X.S. Wang, et al., Cheminformatics meets molecular mechanics: a combined application of knowledge-based pose scoring and physical force fieldbased hit scoring functions improves the accuracy of structure-based virtual screening, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52 (2012) 16-28. |

| [14] | M.D. Eldridge, C.W. Murray, T.R. Auton, G.V. Paolini, R.P. Mee, Empirical scoring functions: I. The development of a fast empirical scoring function to estimate the binding affinity of ligands in receptor complexes, J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 11 (1997) 425-445. |

| [15] | C.A. Sotriffer, P. Sanschagrin, H. Matter, G. Klebe, SFCscore: scoring functions for affinity prediction of protein-ligand complexes, Proteins 73 (2008) 395-419. |

| [16] | J.B. Dunbar Jr., R.D. Smith, C.Y. Yang, et al., CSAR benchmark exercise of 2010: selection of the protein-ligand complexes, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 51 (2011) 2036-2046. |

| [17] | N. Huang, B.K. Shoichet, J.J. Irwin, Benchmarking sets for molecular docking, J. Med. Chem. 49 (2006) 6789-6801. |

| [18] | J.J. Irwin, B.K. Shoichet, ZINC-a free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 45 (2005) 177-182. |

| [19] | C.S. Rapp, C. Schonbrun, M.P. Jacobson, C. Kalyanaraman, N. Huang, Automated site preparation in physics-based rescoring of receptor ligand complexes, Proteins 77 (2009) 52-61. |

| [20] | E.F. Pettersen, T.D.Goddard, C.C.Huang, et al.,UCSF Chimera-a visualizationsystem for exploratory research and analysis, J. Comput. Chem. 25 (2004) 1605-1612. |