b Jiaozuo University, Jiaozuo 454000, China

1. Introduction

Glycosphingolipids (GSLs) play important roles in regulating numerous cellular processes,including cell growth,proliferation and differentiation,cell-cell communication,and oncogenic transformation [1, 2, 3, 4]. Glycosyltransferase catalyzes the transfer of a glycosyl unit to the primary hydroxyl group of sphingolipids to form glycosphingolipids. The involvement of glycosphingolipids in lipid storage diseases has been reported in the literature [5, 6] . For instance,Gaucher disease is believed to result from the accumulation of glucosylceramide,one of the numerous glycosphingolipids [7] . Recently,high levels of glucosylceramide were also observed in different multidrug-resistant cancer cell lines [8] .

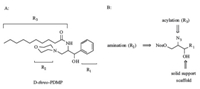

D-threo-1-Phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol (D-threo-PDMP,Fig. 1A),a potent inhibitor of the glucosylceramide synthase,has been extensively studied for its biological functions [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Since its initial discovery in 1980 [20] ,several synthetic routes have been reported [21, 22, 23] . Most of these methods require numerous synthetic transformations and are not suitable for preparing a series of structurally related analogs that would be useful for exploring sphingolipds signaling pathways. To address these limitations,we have designed a solid phase synthetic method that is suitable for preparing large collections of derivatives by automated procedures. 2. Experimental

All reagents and solvents were purchased from Aldrich and used directly without further purification. The Ellman’s dihydropyran resin was purchased from Midwest Bio-Technology with a loading level of 1.3 mmol/g. Flash column chromatography was run on 400-230 mesh silica gel. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 MHz instrument and calibrated using residual undeuterated solvent as an internal reference. Purity of compounds was analyzed by reverse-phase liquid chromatography- mass spectrometry (Agilent Series 1100 LC-MS) with a UV detector at l = 255 nm (reference at 360 nm) and an API-ES ionization source. 2.1. 2-Azido-1-phenyl propane-1,3-diol (4a)

To a solution of NaN3 (5.68 g,87 mmol) in H2O (14 mL) was added CH2Cl2 (23 mL),and the resulting mixture was cooled to 00C,followed by the addition of Tf2O (2.94 mL,17.5 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 00C for 2 h. The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (12 mL × 2). The combined organic solution was washed with saturated Na2CO3 (50 mL). Amine 3a [24] (1.46 g, 8.73 mmol) was dissolved in MeOH (60 mL) and was treated with a solution of NaHCO3 (1.10 g,13.1 mmol) and CuSO4 (14 mg, 0.087 mmol) in H2O (30 mL). More MeOH was then added until a homogeneous solution was obtained,after which was added the freshly prepared TfN3 solution in CH2Cl2. After 12 h at room temperature,the mixture was extracted with CHCl3 (30 mL × 5).

The combined organic solution was washed with brine and dried over Na2SO4. After evaporation under vacuum,the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (EtOAc:hexane = 1:1,v/ v) to give compound 4a as a colorless oil (1.18 g,70%). 1H NMR (400 MHz,CDCl3): δ 7.36 (m,5H),4.78 (m,1H),3.76 (m,0.8H),3.62 (m,1.4H),3.52 (m,0.8H),3.22 (d,0.4H,J = 3.3 Hz),3.04 (d,0.6 H, J = 3.7 Hz),2.72 (t,0.4 H,J = 5.2 Hz),2.48 (t,0.6 H,J = 5.0 Hz). 2.2. 4 Nitrobenzenesulfonic acid 2-azido-3-hydroxy-3-phenylpropyl ester (5a)

To a solution of 4a (1.10 g,5.69 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (25 mL) was added pyridine (0.69 mL,8.53 mmol),followed by the addition of 4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride (1.51 g, 6.81 mmol). After 12 h at room temperature,1 mol/L HCl (20 mL) was added and the aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (15 mL × 2). The combined organic solution was washed with brine and dried over Na2SO4. After evaporation under vacuum,the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (EtOAc:hexane = 1:2) to give compound 5a as yellowish oil (1.72 g,80%). 1H NMR (400 MHz,CDCl3): δ 8.32 (m,2H),8.03 (m, 2H),7.30 (m,5H),4.70 (t,1H,J = 6.8 Hz),4.32 (dd,0.4H,J = 3.1and 10.6 Hz),4.23 (dd,0.4H,J = 7.4 and 10.6 Hz),4.14 (dd,0.6H,J = 3.6 and10.5 Hz),3.95(dd,0.6H,J = 7.1 and 10.5 Hz),3.79 (m,1H),2.98 (bs,0.6H),2.92 (bs,0.4H).

2.3. General procedure for the combinatorial synthesis of PDMP analogs

2.3.1. THP protection for the resin-bound scaffolds (6a)

To a suspension of Ellman’s dihydropyran functionalized polystyrene resin (5 g,6.5 mmol) in anhydrous DCE (50 mL) was added scaffold 5 (13.0 mmol),followed by the addition of PPTS (6.5 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred gently at 50 0C for 12 h. The resin was then washed twice with CH2Cl2 (150 mL). The combined organic solvent was washed with brine to fully recover the excess scaffold,which can be re-subjected for loading without further purification. The resin was further washed with CH2Cl2 (150 mL × 2),MeOH (150 mL × 4) and CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:1, 150 mL × 3) and dried under vacuum to afford resin 6. The loading level of the scaffolds (0.5-0.7 mmol/g) was determined by the weight gains. 2.3.2. Displacement with N,N-disubstituted amines (7)

To a suspension of 6 (0.05 mmol) in NMP (0.5 mL) was added N,N-disubstituted amine (0.5 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred gently at 80 0C for 12 h. The complete conversion from nosylate to amine was confirmed by LC-MS. The resin was washed with DMF (5 mL × 3),CH2Cl2 (5 mL × 3),MeOH (5 mL × 3),CH2Cl2/ MeOH (1:1,5 mL × 3) and dried under vacuum to afford resin 7. In the library production,1 mol/L amines in NMP were used when the reaction was carried out in IRORI Nanokans. 2.3.3. Reduction of azide to amine (6

To a suspension of resin 7 (0.05 mmol) in 1% H2O in THF (0.5 mL) was added trimethylphosphine (0.4 mmol). After 2 h at room temperature,the resin was successively washed with THF (5 mL × 3),CH2Cl2 (5 mL × 3),MeOH (5 mL × 3),CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:1,5 mL × 3) and dried under vacuum to afford resin 8. The complete conversion of azido to amine was confirmed by both IR spectra (disappearance of the azido stretch) and LC-MS (after cleavage from resin). 2.3.4. Acylation with acid chlorides,sulfonyl chlorides or isocyanates (9) and the product cleavage(10)

To a suspension of resin 8 (0.05 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (0.5 mL) was added anhydrous pyridine (1 mmol) (except for isocyanates),followed by the addition of the acylating agents (0.5 mmol). After 12 h at room temperature,the resin was successively washed with DMF (5 mL × 3),CH2Cl2 (5 mL × 3), MeOH (5 mL × 3),CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:1,5 mL × 3) and dried under vacuum to afford resin 9. The completion of the reaction was confirmed by LC-MS. Resin 9 was then cleaved by 10% TFA in CH2Cl2 at room temperature for 1 h to give the desired product 10.

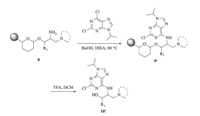

3. Results and discussionWe envisioned PDMP analogs derived from trifunctional hydroxy,azido and nitrosulfonate ester scaffolds shown in Fig. 1B. The 1-hydroxy group serves as an ideal anchor for the solid support. The first diversity element R1 can be obtained from the synthesis of the scaffolds while R2 and R3 elements are introduced on solid phase through simple aminations and acylations respectively (Fig. 1). For example,the synthesis of the phenyl substituted scaffold 5a is outlined in Scheme 1. Since different stereoisomers of PDMP have been shown to exhibit different biological activities [25],it would be of great value to have all four diastereoisomers of PDMP in the library. Thus,the racemic protected serine methyl ester 1 was treated with DIBAL in toluene at -78 0C followed by the addition of phenyl magnesium bromide at room temperature in a one-pot process to give compound 2a as a mixture of diastereomers in 65% yield. This mixture can be easily separated in follow-up studies by wellestablished diastereoselective methods with individual optical pure starting material when it shows positive results in biological assays [26, 27]. The complete deprotection was achieved by the treatment of 4 mol/L HCl in dioxane and methanol to produce amino alcohol 3a in 55% yield. A key step in this synthetic route is azidization of compound 3. Following a literature protocol involving freshly prepared trifyl azide [28],compound 4a was smoothly obtained in 70% yield. The primary hydroxy group was then selectively converted into desired scaffold 5a under standard reaction conditions in 80% yield. The other five scaffolds (5b-f) were prepared similarly. Compounds 5b and 5f were prepared by using corresponding lithiated alkynes followed by Red-Al reductions to form the trans- carbon-carbon double bond.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1 A general protocol for the preparation of scaffolds 5. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1.A solid phase strategy for the synthesis of PDMP analogs. | |

To immobilize the scaffolds to a polystyrene matrix,we chose Ellman’s dihydrophyran linker as it could be cleaved under mild acidic conditions and for its stability under the required reaction conditions (Scheme 2). A similar reaction sequence has been described by Ellman’s group for the synthesis of protease inhibitor directed libraries [29].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Solid phase synthesis of PDMP analogs. | |

The synthetic sequence (Scheme 2) started by loading the scaffolds 5 onto solid support in dichloroethane (DCE) with the presence of pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS). Loading levels of 0.5-0.7 mmol/g were achieved as determined by mass balance of purified material cleaved from the resin. The installation of R2 (Fig. 1B) was achieved by the efficient displacement of nosylate 6 with both cyclic and acyclic N,N-disubstituted amines in NMP at80 0C. The azido group in compound 7 was then reduced to corresponding amines (8) using trimethyl phosphine in terahydrofuran containing 1% water at room temperature. The final diversity elements (R3,Fig. 1B) were introduced by acylations in dichloromethane (DCM) with the presence of pyridine (Py). In addition to acid chlorides,sulfonyl chlorides and isocyanates have also been used as acylating agents to provide corresponding sulfonamide and urea analogs (9). It is noteworthy that we also introduced heterocycles including purine and pyrimidine derivatives via the amination conditions described by Gray and Schultz in their purine library synthesis [30] to further increase the structural diversities. An example is shown in Scheme 3.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. Amination with simple heterocycles. | |

A 5,280-member library (6R1 × 22R2 × 40R3) has been generated by the current method using IRORI Nanokan ㉢system. The library was cleaved from solid support using 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in dichloromethane on the automated cleavage station into 96-well deep well plates. To analyze the quality of the library, 10% of the compounds were analyzed by LC-MS with an average purity over 70%. The average mass yield (80%) has been determined by weight on 10 randomly picked compounds from the library.

This method for the synthesis of PDMP analogs has the following advantages: (1) The versatile azido scaffolds 5 was prepared in a relatively short sequence via a key azidization reaction; (2) Reactions on the solid support avoid tedious workup and difficult purification,particularly for the amino alcohol intermediates; (3) The sulfonamide,urea and heterocycle substituted PDMP analogs can be readily achieved by this method; (4) The use of directed sorting allows us to access large number of compounds in the most efficient way,with a total of 68 (6 + 22 + 40) reactions yielding 5280 compounds. 4. Conclusion

In summary,we report the first solid phase approach to synthesize biologically interesting PDMP analogs. The synthetic schemes include the efficient syntheses of scaffolds 5 in solution and the subsequent derivatization on the solid support. The efficiency of this strategy has been demonstrated by the successful synthesis of a 5280-member library using IRORI Nanokan ⓒsystem. The biological screening on this newly prepared library is now ongoing and the corresponding data will be reported elsewhere.

| [1] | S.I. Hakamori, Glycosphingolipids in cellular interaction, differentiation, and oncogenesis, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 50(1981) 733-764. |

| [2] | Y.A. Hannun, R.M. Bell, Functions of sphingolipids and sphingolipid breakdown products in cellular regulation, Science 243(1989) 500-507. |

| [3] | A. Schwarz, E. Rapaport, K. Hirchberg, et al., A regulatory role for sphingolipids in neuronal growth. Inhibition of sphingolipid synthesis and degradation have opposite effects on axonal branching, J. Biol. Chem. 270(1995) 10990-10998. |

| [4] | L.M. Obeid, C.M. Linardic, L.A. Karolak, et al., Programmed cell death induced by ceramide, Science 259(1993) 1769-1771. |

| [5] | A. Abe, S.R. Wild, W.L. Lee, et al., Agents for the treatment of glycosphingolipid storage disorders, Curr. Durg Metab. 2(2001) 331-338. |

| [6] | T. Koter, A chemical concept for the treatment of Tay-Sachs disease, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 36(1997) 1955-1959. |

| [7] | E.F. Neufeld, Lysosomal storage diseases, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 60(1991) 257-280. |

| [8] | Y. Lavie, H. Cao, S.L. Bursten, et al., Accumulation of glucosylceramides in multidrug-resistant cancer cells, J. Biol. Chem. 271(1996) 19530-19536. |

| [9] | T. Kanto, P. Kalinski, O.C. Hunter, et al., Ceramide mediates tumor-induced dendritic cell apoptosis, J. Immunol. 167(2001) 3773-3784. |

| [10] | T. Iwamoto, S. Fukumoto, K. Kanaoka, et al., Lactosylceramide is essential for the osteoclastogenesis mediated by macrophage-colony-stimulating factor and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand, J. Biol. Chem. 276(2001) 46031-46038. |

| [11] | J. Wei, M. Fujita, A. Sekigawa, et al., Gangliosides protection against lysosomal pathology of synucleinopathies, Autophagy 5(2009) 860-861. |

| [12] | J. Wei, M. Fujita, M. Nakai, et al., Protective role of endogenous gangliosides for lysosomal pathology in a cellular model of synucleinopathies, Am. J. Pathol. 174(2009) 1891-1909. |

| [13] | P. Sántha, O. Oszlács, M. Dux, et al., Inhibition of glucosylceramide synthase reversibly decreases the capsaicin-induced activation and TRPV1 expression of cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons, Pain 150(2010) 103-112. |

| [14] | J.K. Lee, J.K. Kim, S.H. Park, et al., Lactosylceramide mediates the expression of adhesion molecules in TNF-α and IFNγ-stimulated primary cultured astrocytes, Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 15(2011) 251-258. |

| [15] | Y. Kamasaki, T. Nakamura, K. Yoshizaki, et al., Glycosphingolipids regulate ameloblastin expression in dental epithelial cells, J. Dent. Res. 91(2012) 78-83. |

| [16] | H. Fujiwara, K. Ikarashi, Y. Yamazaki, et al., Impairment of hippocampal longterm potentiation and failure of learning in mice treated with d-threo-1-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol, Biomed. Res. 33(2012) 265-271. |

| [17] | L.G. Pescio, N.O. Favale, M.G. Márquez, et al., Glycosphingolipid synthesis is essential for MDCK cell differentiation, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821(2012) 884-894. |

| [18] | L. Li, M. Ståhlman, M. Rutberg, et al., ARF6 regulates neuron differentiation through glucosylceramide synthase, PLoS ONE 8(2013) e60118. |

| [19] | L. Casson, L. Howell, L.A. Mathews, et al., Inhibition of ceramide metabolism sensitizes human leukemia cells to inhibition of BCL2-like proteins, PLoS ONE 8(2013) e54525. |

| [20] | R.R. Vunnam, N.S. Radin, Analogs of ceramide that inhibit glucocerebroside synthetase in mouse brain, Chem. Phys. Lipids 26(1980) 265-278. |

| [21] | S.A. Mitchell, B.D. Oates, H. Razavi, et al., Glycosyltransferase Inhibitors: synthesis of D-threo-PDMP, L-threo-PDMP, and other brain glucosylceramide synthase inhibitors from D-or L-serine, J. Org. Chem. 63(1998) 8837-8842. |

| [22] | K.G. Carson, B. Ganem, N.S. Radin, et al., Studies on morpholinosphingolipids: potent inhibitors of glucosylceramide synthase, Tetrahedron Lett. 35(1994) 2659-2662. |

| [23] | S. Ogawa, T. Mito, E. Taiji, et al., Synthesis and biological evaluation of four stereoisomers of PDMP-analogue, N-(2-decylamino-3-hydroxy-3-phenylprop-1-yl)-β-valienamine, and related compounds, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 7(1997) 1915-1920. |

| [24] | (a) J. Chun, L. He, H.S. Byun, et al., Synthesis of ceramide analogues having the C(4)-C(5) bond of the long-chain base as part of an aromatic or heteroaromatic system, J. Org. Chem. 65(2000) 7634-7640;(b) I.V. Overmeire, S.A. Boldin, K. Venkaraman, et al., Synthesis and biological evaluation of ceramide analogues with substituted aromatic rings or an allylic fluoride in the sphingoid moiety, J. Med. Chem. 43(2000) 4189-4199; Compound 3a was prepared by a modified literature procedure. |

| [25] | J. Inokuchi, A. Mizutani, M. Jimbo, et al., Up-regulation of ganglioside biosynthesis, functional synapse formation, and memory retention by a synthetic ceramide analog(L-PDMP), Biochem, Biophys. Res. Commun. 237(1997) 595-600. |

| [26] | R.S. Coleman, A.J. Carpenter, Diastereoselective addition of vinyl organometallic reagents to L-serinal, Tetrahedron Lett. 33(1992) 1697-1700. |

| [27] | S.D. Jonghe, I.V. Overmeire, S. Poulton, et al., Structure-activity relationship of short-chain sphingoid bases as inhibitors of sphingosine kinase, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 9(1999) 3175-3180. |

| [28] | C.J. Cavender, V.J. Shiner Jr., Trifluoromethanesulfonyl azide. Its reaction with alkyl amines to form alkyl azides, J. Org. Chem. 37(1972) 3567-3569. |

| [29] | E.K. Kick, J.A. Ellman, Expedient method for the solid-phase synthesis of aspartic acid protease inhibitors directed toward the generation of libraries, J. Med. Chem. 38(1995) 1427-1430. |

| [30] | S. Ding, N.S. Gray, Q. Ding, et al., A concise and traceless linker strategy toward combinatorial libraries of 2,6,9-substituted purines, J. Org. Chem. 66(2001) 8273-8276. |