2. 中国地质科学院地质研究所, 自然资源部深地动力学重点实验室, 北京 100037;

3. 南方海洋科学与工程广东省实验室(广州), 广州 511458;

4. 中国地质科学院地质力学研究所, 自然资源部古地磁与古构造重建重点实验室, 北京 100081

2. MNR Key Laboratory of Deep-Earth Dynamics, Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China;

3. Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory(Guangzhou), Guangzhou 511458, China;

4. MNR Key Laboratory of Paleomagnetism and Tectonic Reconstruction, Institute of Geomechanics, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100081, China

根据美国地质勘探局(USGS)统计,2000年以来全球发生7级以上大地震有近300次,造成的人员伤亡达80多万(https://earthquake.usgs.gov/)。在地震和断裂活动关系的传统认知中,大部分地震都是由断裂活动引起的,且地壳中普遍发育的活动断层可分为粘滑断层和蠕滑断层(Reinen, 2000; Gratier et al., 2011, 2013b)。粘滑断层表现为数十年到数百年不活动后突然产生破裂发生大地震,蠕滑断层则主要表现为长期连续且稳定的缓慢滑动(Harris, 2017)。大地震就是沿着断裂传播并释放多年积累的应变的突然滑移事件(Davison, 1901),并且间震期内,粘滑断层主要是闭锁状态,而蠕滑断层长期处于缓慢滑动状态,主要伴随许多微震。另外,蠕滑变形还可分为两种类型:第一种是永久的稳态蠕滑,这与断层岩的特性及其环境有关。在这种情况下,变形具有相当恒定的应变速率(Azzaro et al., 2001; Titus et al., 2006);另一种蠕滑是在地震后几个月到几十年的时间段内的变形,被认为是震后余滑过程,发生在地震断层以下的下地壳,或发生在断层地震部分周围的上地壳(Gao et al., 2000; Barbot et al., 2009)。

根据传统的地震断裂认知,非地震蠕滑变形可以明显地释放活动断裂带的构造应力,减少大地震发生的可能性或降低地震的震级(Gratier et al., 2013b),因此,蠕滑断裂被认为危险性较小。但是,越来越多的证据表明蠕滑断裂比传统认为的要复杂,最近的研究表明蠕滑断层的压力并不总能完全释放,应力值的逐渐增加也可能导致蠕滑部分发生地震破裂,造成重大危险(Chen and Bürgmann, 2017; Harris, 2017),从此可见蠕滑断裂作用研究的重要性。目前,学者们已经对全世界多个蠕滑断层进行研究,如中国海原断裂(Jolivet et al., 2015)、鲜水河断裂(Allen et al., 1991)、中国台湾池上断裂(Lee et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2014)、日本Atotsugawa断裂(Ohzono et al., 2011)、意大利Alto Tiberina低角度正断层(Anderlini et al., 2016)、土耳其North Anatolian断裂(Aslan et al., 2019)、菲律宾莱特岛Philippine断裂(Fukushima et al., 2019)、厄瓜多尔Quito断裂(Mariniere et al., 2020)以及美国著名的San Andreas断层(Steinbrugge and Zacher, 1960; Titus et al., 2006; Richard et al., 2014)等。然而,他们蠕滑机制尚不明确,即使是研究较为成熟的San Andreas断层的蠕滑机制也存在争议。蠕滑断层和粘滑断层截然不同的滑移方式形成的断层岩的物质组成和构造变形特征无疑具有明显的差别,断裂滑移机制的信息总是蕴藏在断层岩物质组成与内部构造中(Schleicher et al., 2010; Gratier et al., 2011; Holdsworth et al., 2011),因此,对断层岩结构构造和矿物成分等进行详细研究是揭示断裂蠕滑机制的有效途径。

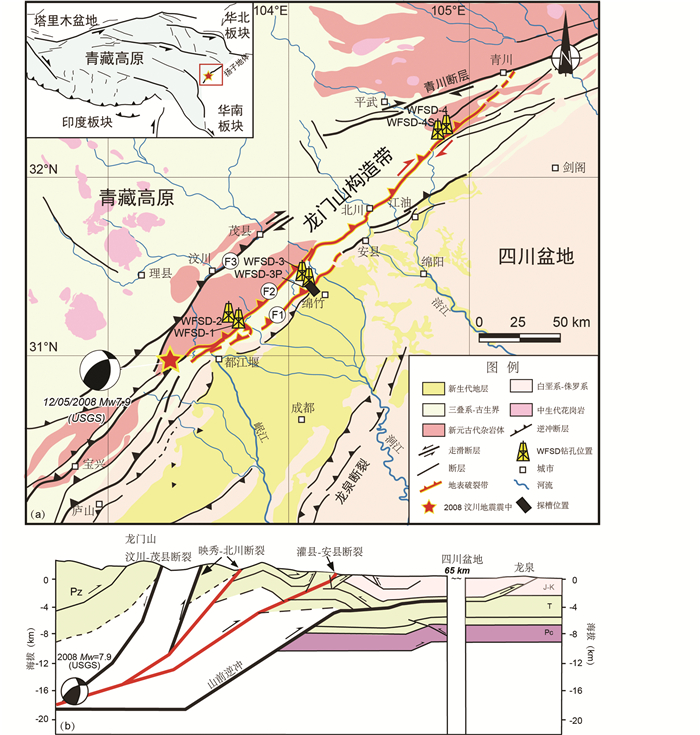

龙门山灌县-安县断裂带位于青藏高原东缘,与映秀-北川断裂、汶川-茂县断裂构成龙门山构造带(图 1)。2008年Mw 7.9(USGS)汶川大地震沿映秀-北川和灌县-安县断裂产生约240~275km和50~80km长的地表破裂带(付碧宏等, 2008; 李勇等, 2009; He et al., 2010; Jia et al., 2010)。据已有研究表明,映秀-北川断裂带内发育多期假玄武玻璃,说明该断裂曾多次发生大地震(Wang et al., 2015, 2019; Zhang et al., 2017),而灌县-安县断裂带多发育褶皱弯曲陡坎和挠曲变形(冉勇康等, 2008; 陈立春等, 2009; 李海兵等, 2010),且断层岩特征表明其具有蠕滑性质(He et al., 2018),但对其蠕滑机制只进行了初步说明,尚没有明确。汶川地震断裂带科学钻探工程(WFSD)为此研究提供了完整的断层岩样品,创造了难得的机遇。本研究基于新的微观结构观察,结合之前的研究结果,将详细分析龙门山灌县-安县断裂带岩石的岩屑分布、矿物组成和微观构造,目的是为了更进一步了解断裂带蠕滑机制,且为将来更好地了解地震周期以及区域防震减灾提供科学依据。

|

图 1 青藏高原东缘龙门山汶川大地震构造背景与WFSD钻孔位置图 (a)龙门山构造地质平面图(据Li et al., 2014修改);(b)龙门山逆冲断裂带垂直剖面(据Hubbard and Shaw, 2009). F1-灌县-安县断裂;F2-映秀-北川断裂;F3-汶川-茂县断裂. Pc-前寒武系;Pz-古生界;T-三叠系;J-侏罗系;K-白垩系 Fig. 1 The tectonic background of Wenchuan earthquake and the locations of WFSD boreholes in the Longmen Shan, eastern Tibet Plateau (a) structural geological plan in the Longmen Shan (modified after Li et al., 2014); (b) vertical profile of Longmen Shan thrust fault zone (after Hubbard and Shaw, 2009). F1-Guanxian-Anxian fault zone; F2-Yingxiu-Beichuan fault zone; F3-Wenchuan-Maoxian fault zone. Pc-Precambrian; Pz-Paleozoic; T-Triassic; J-Jurassic; K-Cretaceous |

龙门山地区位于青藏高原和四川盆地的过渡区域(图 1),是高原强烈隆升和向外扩展的最新位置(Tapponnier et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2007),同时也是我国大陆地震活动和新构造运动十分活跃的典型地区。龙门山构造带在中国南北地震带中段,大约长500km,宽30~60km,由于处在特殊的地理构造位置,且具有复杂的构造变形与强烈的地震活动,因此一直以来都是国际地球科学界广泛关注的对象,尤其在2008年5月12日汶川特大地震发生后,该地区更是成为研究的焦点之一(Xu et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014; 李海兵等, 2018; 靳志同等, 2019)。

龙门山构造带具有复杂的地质结构和演化历史,经过地质学家们多次的勘察和研究,普遍认为龙门山断裂带由三条主干断裂所组成,由西向东分别是汶川-茂县断裂、映秀-北川断裂、灌县-安县断裂,它们在晚新生代以来都具有活动迹象,且可能具有发生强烈地震的能力(许志琴, 2007; Burchfiel, 2008;徐锡伟, 2008; Zhang et al., 2010)。汶川-茂县断裂、映秀-北川断裂、灌县-安县断裂在垂直剖面上呈叠瓦状展布,逆冲推覆方向均指向四川盆地,呈铲状构造发育,直到地下约20多千米处汇聚成一条大剪切带(许志琴等,2018),它们所组成的龙门山构造系控制着青藏高原与四川盆地的相互作用。

灌县-安县断裂是三条主干断裂中最东边的一条,构造形态上呈铲状,倾向北西方向,在约1250m深处倾角约38°,在地表倾角约为60°(Li et al., 2016)。灌县-安县断裂主要发育在中生代地层中,是龙门山三叠纪地层与四川盆地侏罗纪地层的边界,断裂带内发育角砾岩和断层泥。该断裂晚更新世晚期以来的活动构造较为强烈(邓起东等,1994),不仅地貌上切割了河流谷坡,形成断层崖、断层沟槽及垭口等,还控制了晚第四纪地层的分布;晚更新世中期以来以纯逆冲运动为特征,根据构造地貌特征,估计其垂直滑动速率约为0.2mm/y(马保起等,2005)。

2008年Mw 7.9汶川地震造成了多条同震逆冲地表破裂带(图 1),总体走向为NE 10°~30°,主破裂带沿龙门山断裂带的映秀-北川断裂发育,长约275km,破裂带具有逆冲兼右旋走滑性质。次级破裂带沿前山断裂灌县-安县断裂南段发育,长约80km,破裂带基本为纯逆冲性质。另一条长约6km呈NW走向、由SW向NE逆冲并兼有左旋滑动的地表破裂带(小鱼洞破裂带)连接映秀-北川破裂带和灌县-安县破裂带,成为侧向断坡。另外, 在灌县-安县断裂东侧的四川盆地内,由都江堰的聚源到江油发育一条NE向的沙土液化带,可能是四川盆地西部深部盲断裂活动的结果(李海兵等, 2008; Liu-Zeng et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2009; Fu et al., 2011)。其中,灌县-安县破裂带从南端都江堰NW约6km的紫坪铺水库北,向NE不连续分布至彭州市通济场WS侧,然后,从彭州市通济场过白鹿镇、什坊市八角镇、绵竹市九龙镇和汉旺镇,至安县睢水镇南连续分布;主要由地表褶皱弯曲陡坎组成,最大垂直位错3.5~4.0m,破裂带走向NE40°~70°,在一些地区可看见深部断裂面向NW倾,倾角约30°~50°,相对于映秀-北川破裂带要小。

为了认识汶川地震断裂作用和变形过程,地震后的178天(2008年11月6日),由科技部、国土资源部和中国地震局联合行动组织快速实施了汶川地震断裂带科学钻探计划(WFSD)。沿两条主要的汶川地震地表破裂带布置六口科学钻井(WFSD-1、WFSD-2、WFSD-3P、WFSD-3、WFSD-4和WFSD-4S)。这是世界上最快回应大地震的科学钻探,也是第一次研究陆内大地震的科学钻探。其中,WFSD-3P和WFSD-3则位于灌县-安县断裂附近(图 1)。

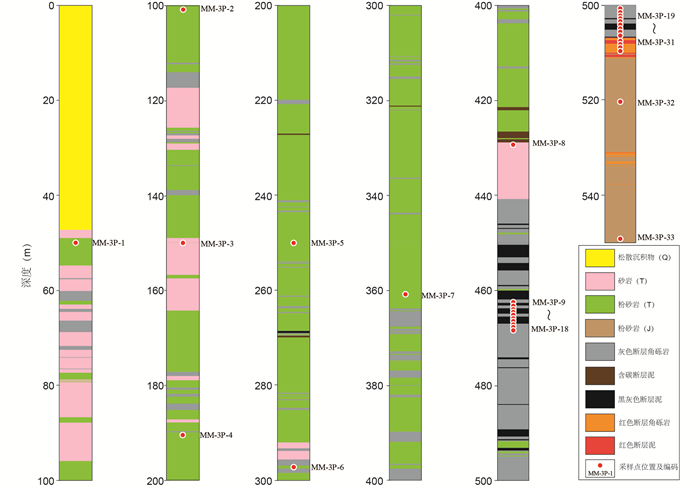

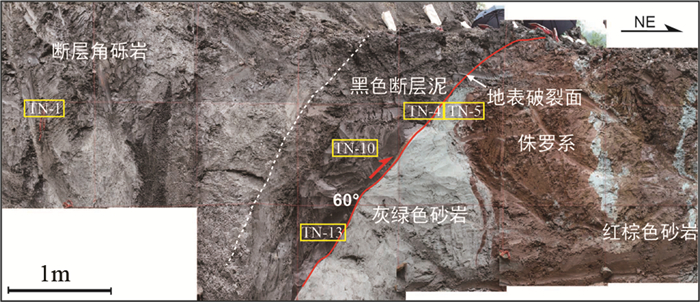

2 样品采集与研究方法 2.1 样品采集本文岩屑分布统计样品为WFSD-3P钻孔463.11~469.04m处具有代表性的断层角砾岩和断层泥岩芯。X射线粉末衍射(XRD)矿物分析样品是采自WFSD-3P钻孔岩芯中灌县-安县断裂带的断层岩及其外部的围岩,包括三叠纪须家河组灰色粉砂岩和侏罗纪棕红色和灰绿色砂岩。33个XRD粉末分析的样品位置如图 2所示,包括8个未蚀变的上盘围岩和破碎带岩石(主要为三叠纪砂岩),23个断层岩样品(10个灰黑色断层泥样品,9个灰黑色断层角砾岩样品,2个棕红色断层泥岩样品,2个棕红色断层角砾岩样品),2个下盘未蚀变侏罗纪围岩(棕红色和灰绿色砂岩)。断层岩显微构造分析样品分别采自WFSD-3P钻孔岩芯以及其附近的九龙探槽(图 3)。

|

图 2 WFSD-3P钻孔岩性柱状图和XRD矿物分析采样位置 Q-第四纪;T-三叠纪;J-侏罗纪 Fig. 2 Lithology chart along WFSD-3 cores and sampling locations Q-Quaternary; T-Triassic; J-Jurassic |

|

图 3 九龙探槽剖面及取样点 TN-探槽北面;红色粗线表示汶川地震地表破裂面位置;红色箭头指示断裂运动方向;白色虚线指示黑色断层泥与断层角砾岩的大致分界线 Fig. 3 The Jiulong trench profile and sampling locations TN-north of the trench; the thick red line represents the location of the surface rupture in Wenchuan earthquake; the red arrow indicates the direction of fault movement; the white dashed line indicates the approximate boundary between the black fault gouge and the fault breccia |

岩屑统计方法主要是通过对所选代表性岩芯进行对半切制,对切至制平面进行高分辨率图像扫描,并通过Photoshop软件对图像进行对比度处理,再通过人工视译对四个粒径范围(< 0.005m、0.005~0.01m、0.01~0.02m和>0.02m)的岩屑数量进行统计,以10cm为单元进行计数,最后将统计结果随深度变化呈现为曲线图。矿物成分分析是将33个代表性样品碾磨成粉末做矿物半定量分析,采用的方法是SY/T 5163—2010沉积岩中黏土矿物和常见非黏土矿物X射线衍射分析方法,测试仪器为X射线衍射仪(D/max-rA)。该实验在北京北达燕园微构分析测试中心有限公司完成。另外,选择具有代表性的地表破裂带和关键岩芯的断层岩制成薄片以进行显微构造观测,主要通过光学显微镜、扫描电镜(SEM)对岩石的矿物组成、颗粒大小、结构、构造及相互关系等进行研究,从而对岩石种类及其变形行为进行分析判断。结合能谱仪(SEM-ESD)可测定其化学成分,来探究断层岩微构造对断裂滑移性质和机制的指示意义。显微构造观测在自然资源部深地动力学重点实验室完成。

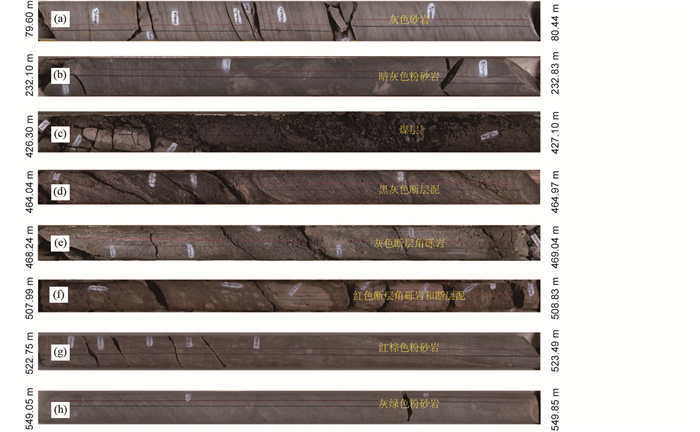

3 灌县-安县断裂带岩石组成 3.1 WFSD-3P钻孔岩性组成灌县-安县断裂带逆冲断裂作用造成晚三叠世须家河组沉积岩(上盘)叠覆在侏罗纪地层(下盘)之上。WFSD-3P钻孔位于灌县-安县断裂带上盘的晚三叠世须家河组中,深约551.5m(图 2),其岩芯主要由晚三叠世须家河组沉积岩(包括灰色粉砂岩和砂岩)、侏罗纪沉积岩(红棕色和灰绿色砂岩和粉砂岩)以及断层岩(断层泥和断层角砾岩)组成,受围岩影响,断裂岩也具有黑灰色和红棕色两种色系,典型岩性的岩芯扫描照片如图 4所示。

|

图 4 WFSD-3P钻孔岩芯主要岩性代表 (a-c)晚三叠世须家河组沉积岩,包括灰色砂岩、暗灰色粉砂岩和煤层;(d-f)断层岩,包括黑灰色断层泥、灰色断层角砾岩、红色断层泥、红色断层角砾岩;(g-h)侏罗纪沉积岩,包括棕红色和灰绿色砂岩 Fig. 4 Main lithologies of the WFSD-3P borehole core (a-c) Triassic Xujiahe Formation sedimentary rocks, including grey sandstone, dark grey siltstone and coal seam; (d-f) fault rocks, including black-gray fault gouge, gray fault breccia, red fault gouge, and red fault breccia; (g-h) Jurassic sedimentary rocks, including brown-red and gray-green sandstones |

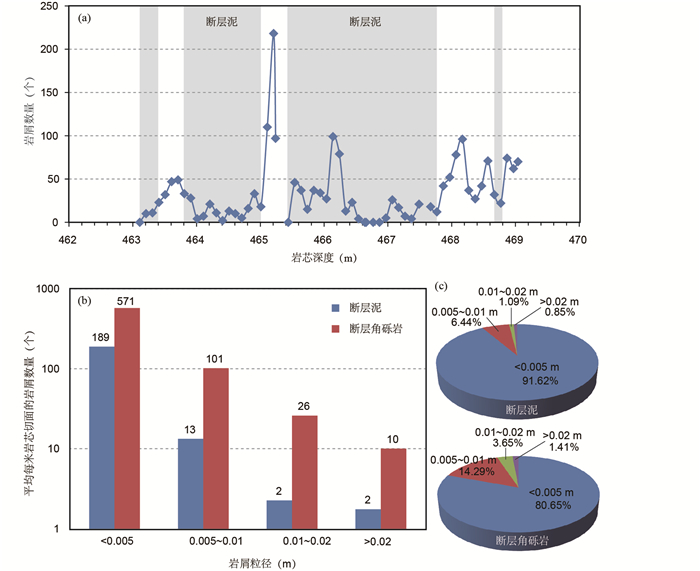

断层岩是围岩在断裂作用过程中发生物理、化学变化所形成的产物。灌县-安县断裂带的断层岩类型主要是断层泥和断层角砾岩,它们均主要由围岩岩屑与细粒基质组成,但二者比例不同,其中的岩屑数量和大小也存在差异。本研究通过对深度为463.11~469.04m的断层泥和断层角砾岩岩芯中的岩屑数量进行统计(图 5a),结果显示断层泥段的岩屑颗粒数量明显小于断层角砾岩,断层泥内部碎屑颗粒数量也有所起伏,局部几乎不见碎屑存在,显示断层泥中还存在次级高应变带。另外,还对断层泥和断层角砾岩中不同大小粒径的岩屑数量进行统计(图 5b,c),断层泥中粒径为 < 0.005m、0.005~0.01m、0.01~0.02m和>0.02m的岩屑数量分别占总数量的91.62%、6.44%、1.09%和0.85%,断层角砾岩中四个粒径范围的岩屑数量百分比分别为80.65%、14.29%、3.65%和1.41%;结果明显展示了断层角砾岩中粒径小于0.005m的岩屑数量是断层泥的3倍多(图 5b),但其所占百分比却小于断层泥,显然,断层角砾岩中粒径大于0.005m的岩屑数量所占百分比高于断层泥(图 5c)。

|

图 5 WFSD-3P钻孔部分断层泥与断层角砾岩的岩屑分布统计图 (a)以10cm为间隔的岩屑数量随岩芯深度变化统计结果,灰色条带为断层泥段;(b)断层泥和断层角砾岩岩屑粒径-数量统计结果;(c)断层泥和断层角砾岩岩屑粒径-百分比统计结果 Fig. 5 Statistical chart of clast distributions of fault gouge and fault breccia in the WFSD-3P borehole (a) the number of clasts vary with core depth at intervals of 10cm, and the gray strip shows the section of the fault gouge; (b) the number of clasts with different grain sizes in fault gouge and fault breccia; (c) the quantitative proportion of clasts with different grain sizes in fault gouge and fault breccia |

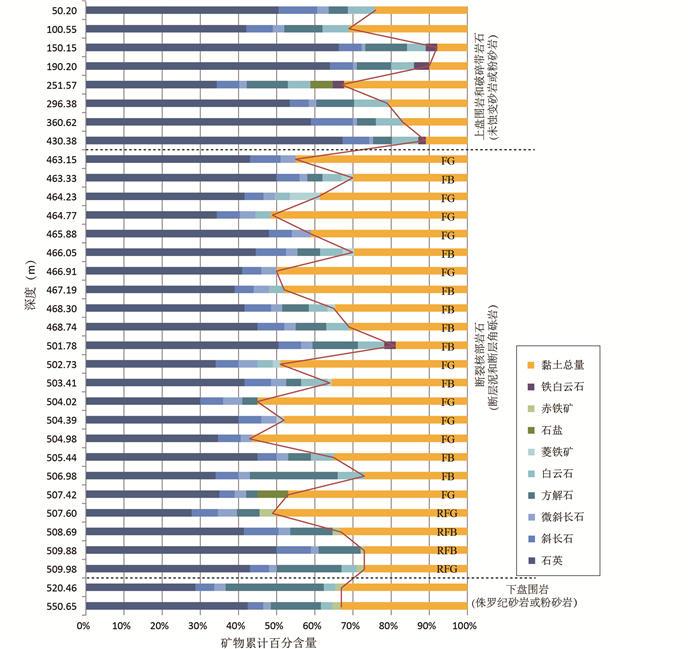

根据WFSD-3P钻孔岩芯中33个样品XRD测试结果显示灌县-安县断裂带围岩、破碎带未蚀变岩石、断层角砾岩和断层泥的矿物成分均可分为可溶解矿物和不溶解矿物。可溶性矿物包括石英、斜长石、微斜长石、碳酸盐矿物等,不溶解矿物以黏土矿物为主(图 6)。从矿物含量变化趋势可见上盘围岩和破碎带未蚀变岩石中的可溶解矿物含量明显大于对应断裂核部断层角砾岩和断层泥,与粘土矿物含量变化趋势恰好相反。断裂核部中矿物含量变化趋势也具有明显规律,断层角砾岩中可溶解矿物含量明显高于断层泥,而粘土矿物含量则小于断层泥,这与上述断层角砾岩中岩屑颗粒明显多于断层泥的现象吻合。断层泥样品的粘土矿物甚至可高达50%以上。然而,这种变化趋势则未显示在断层下盘围岩及其对应断层岩中。从图 6中还可看出只有侏罗纪围岩及其演变成的断层岩含有赤铁矿。铁白云石则几乎只出现在上盘三叠纪砂岩或粉砂岩中,其中501.78m深的断层角砾岩样品也含有少量铁白云石,这可能是由于断层角砾岩中含有相应围岩碎块。石盐只存在与个别样品中,可能与局部流体作用有关。特别的是,黑灰色断层泥样品的测试结果中未见方解石,局部含有少量菱铁矿和白云石,而未蚀变砂岩中完全不含菱铁矿。

|

图 6 WFSD-3P钻孔代表性岩芯样品的XRD矿物含量分析 红色折线表示粘土矿物(不溶矿物)和刚性矿物(可溶解矿物)含量变化趋势;FG-断层泥;FB-断层角砾岩;RFG-红色断层泥;RFB-红色断层角砾岩 Fig. 6 XRD mineral content analysis of representative core samples in the WFSD-3P borehole The red line shows the content variation trend of clay minerals (insoluble minerals) and rigid minerals (soluble minerals). FG-fault gouge; FB-fault breccia; RFG-red fault gouge; RFB-red fault breccia |

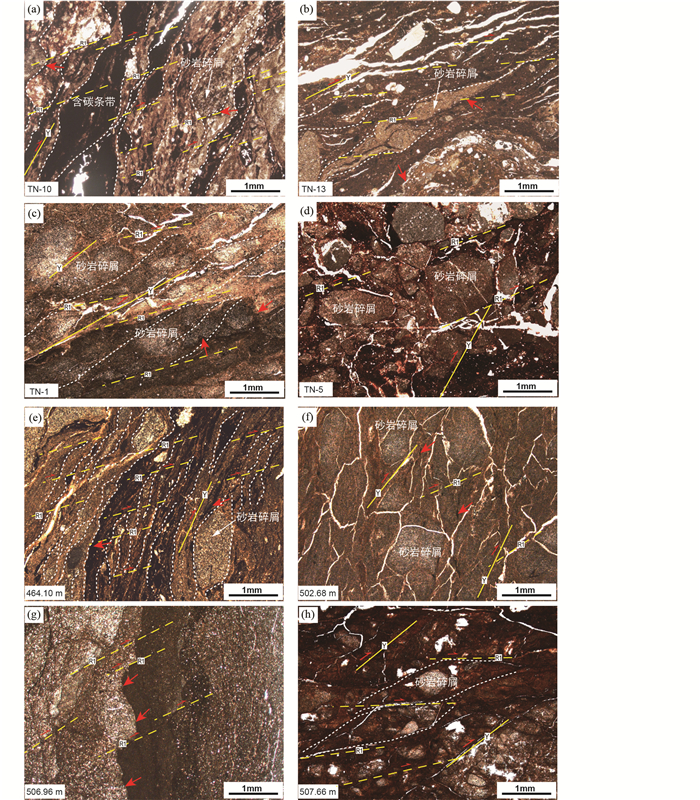

本文综合对九龙探槽和WFSD-3P钻孔的灌县-安县断裂岩进行显微构造分析。根据光学显微镜观察结果显示黑灰色断层泥压溶构造明显,主要表现为面理发育,面理在里德尔剪切体系中发生变形,形成似S-C组构特征(图 7a, b, e),且其中的岩屑随剪切作用发生变形,长轴与面理方向一直,两端呈拖尾构造(图 7a,e),有的碎屑甚至呈现揉皱现象(图 7b),碎屑边缘富集黑色含碳物质(不溶解矿物);基质主要由定向排列的粘土矿物和细小岩屑或刚性矿物颗粒及黑色含碳物质组成,所形成的面理随剪切方向或围绕大碎屑发生变形(图 7a,b,e)。微观显示黑灰色断层角砾岩的砂岩碎屑颗粒明显多于断层泥,其粒度也要大得多,与宏观现象一致,但变形程度则较弱,碎屑呈现出弱定向排列,只有碎屑边缘发生溶解现象(图 7c,f),这种溶解现象多见于碎屑与富含粘土矿物的基质的接触面,但也有发生于两种不同岩性的接触面,如细砂岩和粉砂岩的接触面,溶解边呈波浪状(图 7g)。然而这些构造变形现象则少见于红色断层泥和断层角砾岩中,红色断层角砾岩中的碎屑定向不明显,也少见碎屑拉长现象(图 7d),红色断层泥中的岩屑也多以圆粒状镶嵌于基质中(图 7h)。这可能于断层下盘被动运动相关。

|

图 7 灌县-安县断裂岩光学显微镜下构造特征 (a、b)九龙探槽灰黑色断层泥;(c)九龙探槽黑色断层角砾岩;(d)九龙探槽红色断层角砾岩.样品号标于照片左下角,采样位置如图 3所示; (e)WFSD-3P钻孔灰黑色断层泥;(f、g)WFSD-3P钻孔黑色断层角砾岩;(h)WFSD-3P钻孔红色断层泥.样品深度标于照片左下角.红色箭头指示碎屑颗粒边缘的溶解-沉淀作用;黄线指示里德尔剪切系统;红色半箭头指示剪切方向;白色虚线指示变形的面理 Fig. 7 Structural characteristics of fault rocks in the Guanxian-Anxian fault zone under the optical microscope (a, b) gray-black fault gouge of the Jiulong trench; (c) black fault breccia of the Jiulong trench; (d) red fault breccia of the Jiulong trench. The sample numbers are marked in the lower left corner of the photos, and the sampling location is shown in Figure 3; (e) gray-black fault gouge in WFSD-3P borehole; (f, g) black fault breccia in WFSD-3P borehole; (h) red fault gouge in WFSD-3P borehole. The sample depths are marked in the lower left corner of the photos. The red arrows indicate dissolvation-precipitation at the clasts edges; the yellow lines indicate the Riedel shear system; the red half arrows indicate the direction of shear; the white dotted lines indicate the deformed foliation |

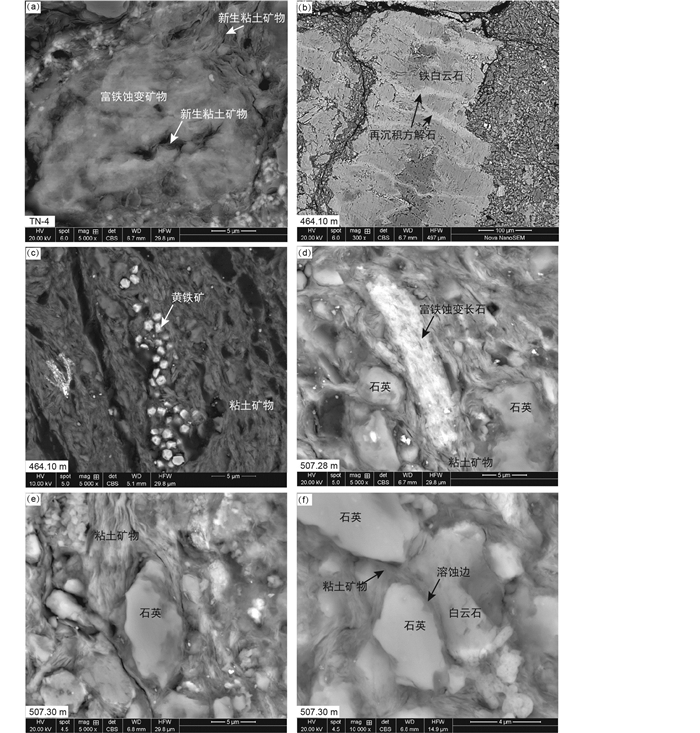

通过扫描电镜对断层泥的基质进行颗粒尺度的微观构造观测,结果显示在流体的辅助及压溶作用下,石英、长石、碳酸盐矿物等发生溶解现象,尤其常见于矿物颗粒边缘,并且发生水岩反应,新生成粘土矿物。图 8a中展示了经历蚀变的矿物富含铁元素,且缝隙及边缘新生出粘土矿物。从图 8b可以看出铁白云石在压溶作用下Ca元素流出并重新在裂隙中沉淀为方解石。铁元素富集于矿物周围及表面,或者与流体反应生成铁硫化物,如黄铁矿(图 8c)。长石在流体和压力作用下则逐渐蚀变成粘土矿物(图 8d)。石英边缘以及其与碳酸盐矿物接触部位发生溶解,与流体反应新生成粘土矿物(图 8e, f)。另外。可溶解矿物的溶解,导致了粘土矿物的被动富集,在剪切应力下作用他们围绕着刚性矿物颗粒边缘滑动、变形,呈定向排列(图 8e, f)。这些显微构造现象与矿物成分分析结果一致,显示出经过断裂作用演变成的断层泥富含粘土矿物和含铁矿物。

|

图 8 灌县-安县断裂岩扫描电镜下显微构造特征 (a)九龙探槽灰黑色断层泥, 样品号标于照片左下角;(b-f)WFSD-3P钻孔灰黑色断层泥,样品深度标于照片左下角 Fig. 8 Microstructure characteristics of fault rocks in the Guanxian-Anxian fault zone under the scanning electron microscope (a) gray-black fault gouge of the Jiulong trench, the sample numbers are marked in the lower left corner of the photos, and the sampling location is shown in Fig. 3; (b-f) gray-black fault gouge of WFSD-3P borehole, the sample depths are marked in the lower left corner of the photo |

目前至少有三种主要的机制可以解释断层弱化和蠕滑变形的增强。第一种与孔隙流体超压有关(Etheridge et al., 1984; Sleep and Blanpied, 1992; Chester et al., 1993),但后来研究表明,这一机制并不能单独解释该断层的弱化及其观测到的蠕滑速率(Fulton and Saffer, 2009; Holdsworth et al., 2011; Mittempergher et al., 2011)。第二种变形机制是摩擦滑移,该机制需要具有速度增强行为的弱矿物,如滑石、蒙脱石和其他低摩擦系数粘土矿物。因此,这一机制既取决于岩石成分,又受温度和压力条件控制(Moore and Rymer, 2007; Carpenter et al., 2009, 2011; Collettini et al., 2009; Tembe et al., 2010; Lockner et al., 2011)。实验还表明,低摩擦系数物质还有利于抑制地震成核(Ikari et al., 2011)。地震粘滑和非震蠕滑这两种滑移方式的出现与滑动面的摩擦特性相关,滑移带物质的摩擦性能可分为速度弱化和速度强化两大类,这意味着断层滑移模式的转变通常与断层滑移带物质的变化有关(Kocharyan et al., 2017)。有学者提出断层泥的速度依赖性可以解释断层不稳定粘滑和稳定的非震滑移行为,即速度弱化的物质产生不稳定的粘滑运动,而速度强化的物质表现出稳定的摩擦滑移(He et al., 2016)。第三种能够适应大的非震变形而不产生热量的蠕滑过程是压溶作用蠕变(Schleicher et al., 2009; Gratier et al., 2011; Holdsworth et al., 2011)。这种变形机制是一种应力驱动的流体辅助传质过程,在上地壳岩石中得到广泛认识(Gratier et al., 2013a)。此外,实验和自然观察都表明,摩擦和压溶作用机制可相互作用,结合为一种摩擦-粘滞蠕滑机制来调节滑动(Bos et al., 2000; Bos and Spiers, 2002; Jefferies et al., 2006)。

压溶作用是个非常缓慢的过程(应变速率小于10-10s-1, Richard et al., 2014),从上文对灌县-安县断裂岩的显微观测结果可以看出压溶作用变形普遍存在于断裂带中(图 7和图 8),特别是在断层泥中,这也是导致断层泥中岩屑数量较少,且粘土矿物较多的主要原因(图 5和图 6),从图 5和图 6中,我们可以看出断层泥带中还发育有次级高应变带,几乎不存在岩屑,粘土矿物含量大于50%,这对断层蠕滑具有重要贡献,也说明灌县-安县断裂带大部分位移发生在非常缓慢的速率下,但断层核部并非均匀蠕滑。本研究观测结果还显示矿物溶解作用多发生在可溶性矿物与粘土矿物接触的边界或不同矿物接触带(图 7a-c, e-g和图 8e, f),该结果和前人自然观察和实验研究结果一致,表明在所有条件相同的情况下,不溶解矿物和可溶性矿物的混合物在压力作用下比只有可溶物组成的单矿物岩石更容易变形(Zubtsov et al., 2004; Gratier, 2011)。这是由于沿层状硅酸盐与可溶矿物边界扩散转移物质速率比沿可溶矿物边界快得多,该现象在自然界和实验中均有发现(Zubtsov et al., 2004; Gratier, 2011)。并且,由于可溶性矿物物质的转移,层状硅酸盐矿物等不溶性矿物被动富集,这有利于溶解作用的加强,由此可见压溶作用与粘土矿物的富集相辅相成。

此外,从WFSD-3P钻孔断层岩矿物组成研究结果可见,相较于未变形的围岩,断层岩粘土矿物含量增长,可溶性矿物,如石英、长石、碳酸盐矿物等含量减小(图 6)。实验表明,断层泥矿物学对断层带摩擦特性具有重要影响作用(Carpenter et al., 2009; Ikari et al., 2011),层状硅酸盐矿物含量增加导致摩擦减少,沿层状硅酸盐矿物的摩擦比沿其他矿物(石英和长石,甚至是岩盐)的摩擦更容易(Bos et al., 2000; Bos and Spiers, 2002)。并且,从微观构造观察和矿物组成分析结果可以推断,在流体和压溶过程共同作用下,粘土矿物含量的增长并非全部是由可溶解矿物含量减少被动富集造成的,还有部分是由于水岩作用新生形成的(图 6和图 8),这当中还伴随着富铁矿物的生成。有学者通过室内摩擦实验确定的圣安德烈亚斯蠕滑段的平均摩擦系数在0.16~0.21之间(Carpenter et al., 2011; Lockner et al., 2011)。Tembe et al.(2010)表明在粘土矿物和石英混合的情况下,粘土含量必须大于50%,摩擦系数才能达到小于0.2。据测试结果可知灌县-安县断裂带断层泥的粘土矿物含量确有大于50% (图 6),满足低摩擦系数条件。实验研究还表明在湿润条件下更少的层状硅酸盐的含量可导致低摩擦系数(Collettini et al., 2009; Niemeijer et al., 2010)。因此,低摩擦系数蠕滑机制的最重要参数是断层核的矿物组成,即弱矿物含量应足够高。

从灌县-安县断裂岩的显微构造中观察到粘土矿物沿许多微剪切面滑动形成类似S-C的组构,或随矿物碎屑旋转而滑动形成碎屑-粘土组构(图 7a, b, e和图 8e, f)。除此之外,在灌县-安县断层泥显微构造中还可见新形成的多种方向生长的粘土矿物和折叠和扭结的粘土矿物(图 8a; He et al., 2018),这些均是强应变断层泥中脆弱组构的表现(Janssen et al., 2012)。粘土矿物的滑动可能与微剪切面的发育和多矿物碎屑或颗粒的旋转有关,所有这些刚性碎屑的旋转拖拽使得面理发生变形。如果碎屑不能在两个剪切面之间旋转,系统就会被锁定,继续变形的唯一方法是不断地形成新的面理,叠加在之前的面理上,或者破坏碎屑(Richard et al., 2014)。压溶作用对蠕滑断裂带所有矿物颗粒碎屑边界滑动都有贡献,这与层状硅酸盐岩石的摩擦-粘性流动模型相一致(Bos et al., 2000; Bos and Spiers., 2002; Jefferies et al., 2006),该模型将摩擦和扩散颗粒滑动变形结合在一起。颗粒滑移是唯一能适应无限剪切过程的机制(Ashby and Verrall, 1973),这正是稳态蠕滑所需要的。

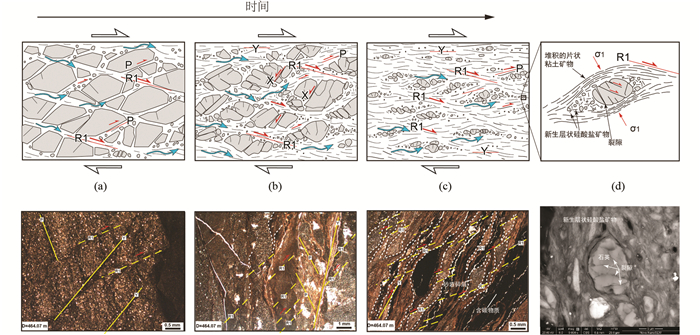

本研究的显微观察和成分分析记录了蠕滑断裂带岩石在压力和流体的作用下随时间变化的变形过程(图 9,He et al., 2018)。在最初较坚硬的岩石中,发生压裂,促进流体进入岩石内(图 9a);在流体和压力作用下,可溶性矿物发生溶解,颗粒变小,不溶解矿物如层状硅酸盐被动富集,加上与流体的反应,新生层状硅酸盐矿物形成,优先沿已存在的裂隙分布(图 9b),因此粘土矿物含量逐渐增加,岩石逐渐软化。随着压溶作用的增强,颗粒尺寸减小,层状硅酸盐矿物不断形成,粘土矿物沿剪切面和颗粒边缘滑动,形成碎屑-粘土组构(图 9c),详见图 9d。因此,灌县-安县断裂蠕滑机制结合了压溶作用和摩擦-颗粒滑移机制。

|

图 9 蠕滑断层在压溶作用下断层岩变形过程的示意图及对应的显微照片(据He et al., 2018修改) (a)受里德尔剪切系统的作用,围岩块体在断裂过程中发生裂隙,形成多个棱角状碎块或具有发散裂缝的矿物颗粒; (b)棱角状碎块或矿物颗粒在里德尔剪切体系中连续破碎并在压溶作用中溶解,使颗粒尺寸减小,在流体作用下形成以石英颗粒和层状硅酸盐矿物为主的细粒基质, 新形成的层状硅酸盐矿物和细粒的石英颗粒在剪切方向(R1、P和Y)上定向排列; (c)残留的碎屑或矿物颗粒不断变小,新形成的层状硅酸盐矿物在增加,同时由于随着细粒物质的增加,水岩反应面积增加,从而压溶作用增强;以往新形成的层状硅酸盐矿物包裹着残余碎屑或矿物颗粒,并随着R1和Y剪方向堆积变形,呈现出粘土-碎屑组合的结构;随机取向的(新形成的)粘土矿物颗粒间的空隙形成;残余碎屑或矿物颗粒沿P和Y剪切方向排列; (d)被放大的压溶构造.红色半箭头为剪切方向,红色箭头为主压应力方向, 蓝色箭头表示流体流动 Fig. 9 Schematic depiction and corresponding photomicrographs of deformation processes of fault rocks under pressure solution in a creeping fault (modified after He et al., 2018) (a) a host rocks patch is fractured during faulting to form several angular clasts or mineral grains with divergent cracks subjected to the Riedel shear system; (b) the angular clasts or mineral grains are continuously are fractured in the Riedel shear system and dissolved under pressure solution, to decrease in grain size and form a fine-grained matrix mainly composed of quartz grains and phyllosilicate minerals under the effect of fluids; the newly formed phyllosilicate minerals and fine-grained quartz grains are aligned in the shear directions (R1, P, and Y); (c) the residual clasts or mineral grains are continuously getting smaller, and newly formed phyllosilicate minerals are increasing, as pressure solution becomes enhanced due to increasing fluid-rock contact areas with increasing fine-grained materials. Previous newly formed phyllosilicate minerals envelope the residual clasts or mineral grains and are stacked and deformed with R1 and Y shears, which show the fabric of CCAs. Randomly oriented (newly formed) clay particles form in intergranular spaces. The residual clasts or mineral grains are aligned in P and Y shear directions; (d) amplified details of residual clasts or mineral grains, red half arrows show shear directions, and red arrows show the direction of the principal compressive stress; blue arrows represent fluid flows |

活跃的蠕滑断层段通常发生小地震,且在时间和地点上经常有规律地重复发生,学者们通常通过这个特征推断断层的蠕滑行为(Nadeau et al., 1995; Senobari and Funning, 2019)。灌县-安县断裂带同样具有这样的特征。郑晨等(2015)通过滑动窗口的波形互相关方法对布设在灌县-安县断裂周边17个流动地震台的连续地震记录进行处理,识别出很多重复地震,这表明灌县-安县断裂一直比较脆弱,汶川地震后并未愈合。

上文阐述了断裂蠕滑的机制,那其发生地震的机制是什么呢?虽然强烈的破裂可通过减小传质距离来促进压溶作用,但之后的裂隙愈合可增加传质距离来减缓蠕滑,从而强化岩石。应力可能因此累积,导致新的脆性变形,这将加速压溶作用蠕滑的速度,并重复变形形成一个周期(Gratier et al., 1999)。由于断裂流体局部差异性,蠕滑断裂的部分区域将会出现地震破裂-压溶蠕滑-愈合强化-应力积累-地震破裂的循环,因此会出现重复地震现象。我们可以从碎屑方解石脉中发现这种可能性的存在(图 8b)。然而,灌县-安县断裂带不仅具有这种蠕滑断裂重复地震的特征,还在2008年Mw 7.9汶川地震中发生破裂,这又是如何造成的呢?虽然可取到的断层岩样品中少有方解石脉,这与长期流体性质相关,但当下地壳或地幔运动发生波动时,流体性质可能发生改变,水岩作用可造成断裂带中存在大量的方解石脉体,这样往往会加强岩石,因为与可溶性和不溶性颗粒的混合物相比,溶解单矿物岩石更加困难(Gratier et al., 2013b),在脉体的晶粒尺度上不易发生,只在薄流体相所在的脉体边界处会发生溶解。这最终导致大面积断层裂缝愈合,因此变得越来越强,应力大量积累,这可能正是大地震破裂过程会发生的位置(Richard et al., 2014)。

根据传统认知,大地震不会在断层蠕滑段上成核,而是在蠕滑和闭锁段之间的边界或者闭锁段成核(Scholz, 1998)。但近些年有研究表明虽然断层可以通过蠕滑容纳其大部分滑动来降低地震危险性,但孕震区以下相对稳定的震间蠕滑仍可能导致整体应力积累,最终导致地震破裂(Harris,2017)。或是,断层闭锁段成核的大地震可能通过近地表断层蠕滑段或薄弱部分上倾而导致破裂(Noda and Lapusta, 2013;Maurer and Johnson, 2014)。并且,有学者认为断层的变形行为也可能随着断层性质和应力状态的改变从连续的蠕滑变形向突发的地震破裂转变(McLaskey and Kilgore, 2013;Rosenau et al., 2019)。另外,还有学者认为断层蠕滑可能是大地震的后作用(Cakir et al., 2012)。然而,Bilham et al.(2016)并不认可该观点,表明尽管有些地震确实存在一些长期影响,但断层蠕滑大部分都是由于构造载荷造成。

到目前为止,人们对地震机制、地震概率、地震爆发的很多研究都受传统观点的约束,没有一个简单的非地震蠕滑和地震能量释放的模型能够解释所有的断层运动现象。断层蠕滑与大地震之间的关系仍然没有得到解决,还有待进一步研究。

6 结论本文通过对具有蠕滑性质的龙门山灌县-安县断裂带九龙探槽和WFSD-3P钻孔断层岩物质组成和显微构造的进一步分析,得到以下结论:

(1) 压溶作用造成灌县-安县断裂带断层岩中可溶性矿物,如石英、长石、碳酸盐矿物等发生溶解,粘土矿物等不溶性物质富集,面理增加,呈拖尾构造、似S-C组构、碎屑-粘土组构等蠕滑变形构造,弱化了断层。

(2) 断层泥粘土矿物含量高达50%以上,是造成灌县-安县断裂带低摩擦性质的主要因素,也是促进颗粒滑移和压溶作用不断进行的关键所在。因此,灌县-安县断裂带的蠕滑过程主要是压溶作用和摩擦-颗粒滑移机制共同作用。

(3) 在地壳应力状态、流体性质等外部环境以及断层内部物质和结构多种因素复杂的作用下,蠕滑断裂局部可发生重复地震现象,甚至可发生大地震,但断层蠕滑与大地震之间的准确关系仍然需要进一步探究。

致谢 汶川地震断裂科学钻研工程实验中心魏金川和吴建国在薄片制备和采集样品时给予了帮助;中国地质科学院地质研究所施斌博士在观察扫描电镜时给予了帮助;二位审稿人中国地质大学(北京)刘俊来教授、西北大学董云鹏教授以及本刊编辑对本文提出了宝贵的修改意见;在此一并表示衷心的感谢!

Allen CR, Luo ZL, Qian H, Wen XZ, Zhou HW and Huang WS. 1991. Field study of a highly active fault zone: The Xianshuihe fault of southwestern China. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 103(9): 1178-1199 DOI:10.1130/0016-7606(1991)103<1178:FSOAHA>2.3.CO;2 |

Anderlini L, Serpelloni E and Belardinelli ME. 2016. Creep and locking of a low-angle normal fault: Insights from the Altotiberina fault in the Northern Apennines (Italy). Geophysical Research Letters, 43(9): 4321-4329 DOI:10.1002/2016GL068604 |

Ashby MF and Verrall RA. 1973. Diffusion-accommodated flow and superplasticity. Acta Metallurgica, 21(2): 149-163 DOI:10.1016/0001-6160(73)90057-6 |

Aslan G, Lasserre C, Cakir Z, Ergintav S, Özarpaci S, Dogan U, Bilham R and Renard F. 2019. Shallow creep along the 1999 Izmit earthquake rupture (Turkey) from GPS and high temporal resolution interferometric synthetic aperture radar data (2011-2017). Journal of Geophysical Research, 124(2): 2218-2236 |

Azzaro R, Mattia M and Puglisi G. 2001. Fault creep and kinematics of the eastern segment of the Pernicana fault (Mt. Etna, Italy) derived from geodetic observations and their tectonic significance. Tectonophysics, 333(3-4): 401-415 DOI:10.1016/S0040-1951(01)00021-X |

Barbot S, Fialko Y and Bock Y. 2009. Postseismic deformation due to the Mw 6.0 2004 Parkfield earthquake: Stress-driven creep on a fault with spatially variable rate-and-state friction parameters. Journal of Geophysical Research, 114(B7): B07405 |

Bilham R, Ozener H, Mencin D, Dogru A, Ergintav S, Cakir Z, Aytun A, Aktug B, Yilmaz O, Johnson W and Mattioli G. 2016. Surface creep on the North Anatolian Fault at Ismetpasa, Turkey, 1944-2016. Journal of Geophysical Research, 121(10): 7409-7431 |

Bos B, Peach CJ and Spiers CJ. 2000. Frictional-viscous flow of simulated fault gouge caused by the combined effects of phyllosilicates and pressure solution. Tectonophysics, 327(3-4): 173-194 DOI:10.1016/S0040-1951(00)00168-2 |

Bos B and Spiers CJ. 2002. Frictional-viscous flow of phyllosilicate-bearing fault rock: Microphysical model and implications for crustal strength profiles. Journal of Geophysical Research, 107(B2): 2028 DOI:10.1029/2001JB000301 |

Burchfiel BC, Royden LH, van der Hilst RD, Hager BH, Chen Z, King RW, Li C, Lü J, Yao H and Kirby E. 2008. A geological and geophysical context for the Wenchuan earthquake of 12 May 2008, Sichuan, People's Republic of China. GSA Today, 18(7): 4-11 DOI:10.1130/GSATG18A.1 |

Cakir Z, Ergintav S, Ozener H, Dogan U, Akoglu AM, Meghraoui M and Reilinger R. 2012. Onset of aseismic creep on major strike-slip faults. Geology, 40(12): 1115-1118 DOI:10.1130/G33522.1 |

Carpenter BM, Marone C and Saffer DM. 2009. Frictional behavior of materials in the 3D SAFOD volume. Geophysical Research Letters, 36(5): L05302 |

Carpenter BM, Marone C and Saffer DM. 2011. Weakness of the San Andreas Fault revealed by samples from the active fault zone. Nature Geoscience, 4(4): 251-254 |

Chen KH and Bürgmann R. 2017. Creeping faults: Good news, bad news?. Reviews of Geophysics, 55(2): 282-286 DOI:10.1002/2017RG000565 |

Chen LC, Ran YK, Chen J, Wang H, Shi X, Liu JF and Dong SP. 2009. Geological and geomorphic evidence for repeatedly occurring severe earthquakes on fronter-range fault of Longmenshan, China. Quaternary Sciences, 29(3): 472-483 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Chester FM, Evans JP and Biegel RL. 1993. Internal structure and weakening mechanisms of the San Andreas Fault. Journal of Geophysical Research, 98(B1): 771-786 DOI:10.1029/92JB01866 |

Collettini C, Niemeijer A, Viti C and Marone C. 2009. Fault zone fabric and fault weakness. Nature, 462(7275): 907-910 DOI:10.1038/nature08585 |

Davison C. 1901. The great Japanese earthquake of October 28, 1891. Geogr. J., 17(6): 635-655 DOI:10.2307/1775216 |

Deng QD, Chen SF and Zhao XL. 1994. Tectonics, scismisity and dynamics of Longmenshan Mountains and its adjacent regions. Seismology and Geology, 16(4): 389-403 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Etheridge MA, Wall VJ, Cox SF and Vernon RH. 1984. High fluid pressures during regional metamorphism and deformation: Implications for mass transport and deformation mechanisms. Journal of Geophysical Research, 89(B6): 4344-4358 DOI:10.1029/JB089iB06p04344 |

Fu BH, Shi PL and Zhang ZW. 2008. Spatial characteristics of the surface rupture produced by the Ms 8.0 Wenchuan earthquake using high-resolution remote sensing imagery. Acta Geologica Sinica, 82(12): 1679-1687 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Fu BH, Shi PL, Guo HD, Okuyama S, Ninomiya Y and Wright S. 2011. Surface deformation related to the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, and mountain building of the Longmen Shan, eastern Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 40(4): 805-824 DOI:10.1016/j.jseaes.2010.11.011 |

Fukushima Y, Hashimoto M, Miyazawa M, Uchida N and Taira TA. 2019. Surface creep rate distribution along the Philippine fault, Leyte Island, and possible repeating of Mw ~6.5 earthquakes on an isolated locked patch. Earth, Planets and Space, 71(1): 118 DOI:10.1186/s40623-019-1096-5 |

Fulton PM and Saffer DM. 2009. Potential role of mantle-derived fluids in weakening the San Andreas Fault. Journal of Geophysical Research, 114(B7): B07408 |

Gao SS, Silver PG and Linde AT. 2000. Analysis of deformation data at Parkfield, California: Detection of a long-term strain transient. Journal of Geophysical Research, 105(B2): 2955-2967 DOI:10.1029/1999JB900383 |

Gratier JP, Renard F and Labaume P. 1999. How pressure solution creep and fracturing processes interact in the upper crust to make it behave in both a brittle and viscous manner. Journal of Structural Geology, 21(8-9): 1189-1197 DOI:10.1016/S0191-8141(99)00035-8 |

Gratier JP. 2011. Fault permeability and strength evolution related to fracturing and healing episodic processes (years to millennia): The role of pressure solution. Oil & Gas Science and Technology, 66(3): 491-506 |

Gratier JP, Richard J, Renard F, Mittempergher S, Doan ML, Di Toro G, Hadizadeh J and Boullier AM. 2011. Aseismic sliding of active faults by pressure solution creep: Evidence from the San Andreas Fault observatory at depth. Geology, 39(12): 1131-1134 DOI:10.1130/G32073.1 |

Gratier JP, Dysthe DK and Renard F. 2013a. The role of pressure solution creep in the ductility of the Earth's upper crust. Advances in Geophysics, 54: 47-179 DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-380940-7.00002-0 |

Gratier JP, Thouvenot F, Jenatton L, Tourette A, Doan ML and Renard F. 2013b. Geological control of the partitioning between seismic and aseismic sliding behaviours in active faults: Evidence from the Western Alps, France. Tectonophysics, 600: 226-242 DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2013.02.013 |

Harris RA. 2017. Large earthquakes and creeping faults. Reviews of Geophysics, 55(1): 169-198 |

He CR, Tan WB and Zhang L. 2016. Comparing dry and wet friction of plagioclase: Implication to the mechanism of frictional evolution effect at hydrothermal conditions. Journal of Geophysical Research, 121(9): 6365-6383 |

He HL, Wei ZY, Shi F and Sun HY. 2010. Near-field postseismic deformation along the rupture of 2008 Wenchuan earthquake and its implications. Chinese Science Bulletin, 55(23): 2535-2541 DOI:10.1007/s11434-010-3259-4 |

He XL, Li HB, Wang H, Zhang L, Xu ZQ and Si JL. 2018. Creeping along the Guanxian-Anxian fault of the 2008 Mw 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake in the Longmen Shan, China. Tectonics, 37(7): 2124-2141 DOI:10.1029/2017TC004820 |

Holdsworth RE, van Diggelen EWE, Spiers CJ, de Bresser JHP, Walker RJ and Bowen L. 2011. Fault rocks from the SAFOD core samples: Implications for weakening at shallow depths along the San Andreas Fault, California. Journal of Structural Geology, 33(2): 132-144 DOI:10.1016/j.jsg.2010.11.010 |

Hubbard J and Shaw JH. 2009. Uplift of the Longmen Shan and Tibetan Plateau, and the 2008 Wenchuan (M=7.9) earthquake. Nature, 458(7235): 194-197 DOI:10.1038/nature07837 |

Ikari MJ, Marone C and Saffer DM. 2011. On the relation between fault strength and frictional stability. Geology, 39(1): 83-86 |

Janssen C, Kanitpanyacharoen W, Wenk HR, Wirth R, Morales L, Rybacki E, Kienast M and Dresen G. 2012. Clay fabrics in SAFOD core samples. Journal of Structural Geology, 43: 118-127 DOI:10.1016/j.jsg.2012.07.004 |

Jefferies SP, Holdsworth RE, Shimamoto T, Takagi H, Lloyd GE and Spiers CJ. 2006. Origin and mechanical significance of foliated cataclastic rocks in the cores of crustal-scale faults: Examples from the Median Tectonic Line, Japan. Journal of Geophysical Research, 111(B12): B12303 |

Jia D, Li YQ, Lin AM, Wang MM, Chen W, Wu XJ, Ren ZK, Zhao Y and Luo L. 2010. Structural model of 2008 Mw 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake in the rejuvenated Longmen Shan thrust belt, China. Tectonophysics, 491(1-4): 174-184 DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2009.08.040 |

Jin ZT, Wan YG, Wang FC, Yang F and Li Y. 2019. Evidence on the stress effect of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake rupture to the northeast. Journal of Geodesy and Geodynamics, 39(8): 783-789 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Jolivet R, Candela T, Lasserre C, Renard F, Klinger Y and Doin MP. 2015. The burst-like behavior of aseismic slip on a rough fault: The creeping section of the Haiyuan fault, China. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 105(1): 480-488 DOI:10.1785/0120140237 |

Kocharyan GG, Novikov VA, Ostapchuk AA and Pavlov DV. 2017. A study of different fault slip modes governed by the gouge material composition in laboratory experiments. Geophysical Journal International, 208(1): 521-528 DOI:10.1093/gji/ggw409 |

Lee JC, Angelier J, Chu HT, Hu JC, Jeng FS and Rau RJ. 2003. Active fault creep variations at Chihshang, Taiwan, revealed by creep meter monitoring, 1998-2001. Journal of Geophysical Research, 108(B11): 2528 DOI:10.1029/2003JB002394 |

Li HB, Fu XF, Van der Woerd J, Si JL, Wang ZX, Hou LW, Qiu ZL, Li N, Wu FY, Xu ZQ and Tapponnier P. 2008. Co-seisimic surface rupture and dextral-slip oblique thrusting of the Ms 8.0 Wenchuan earthquake. Acta Geologica Sinica, 82(12): 1623-1643 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Li HB, Si JL, Pei JL, Fu XF, Wang ZX, Li N, Hou LW, Wu FY and Pan JW. 2010. Investigating the surface rupture process of the Wenchuan earthquake (Ms 8.0). Quaternary Sciences, 30(4): 677-698 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Li HB, Xu ZQ, Niu YX, Kong GS, Huang Y, Wang H, Si JL, Sun ZM, Pei JL, Gong Z, Chevalier ML and Liu DL. 2014. Structural and physical property characterization in the Wenchuan Earthquake Fault Scientific Drilling Project Hole 1 (WFSD-1). Tectonophysics, 619-620: 86-100 DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2013.08.022 |

Li HB, Wang H, Yang G, Xu ZQ, Li TF, Si JL, Sun ZM, Huang Y, Chevalier ML, Zhang WJ and Zhang JJ. 2016. Lithological and structural characterization of the Longmen Shan fault belt from the 3rd hole of the Wenchuan Earthquake Fault Scientific Drilling Project (WFSD-3). International Journal of Earth Sciences, 105(8): 2253-2272 DOI:10.1007/s00531-015-1285-9 |

Li HB, Xu ZQ, Wang H, Zhang L, He XL, Si JL and Sun ZM. 2018. Fault behavior, physical properties and seismic activity of the Wenchuan earthquake fault zone: Evidences from the Wenchuan earthquake Fault Scientific Drilling project (WFSD). Chinese Journal of Geophysics, 61(5): 1680-1697 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Li Y, Huang RQ, Densmore AL, Zhou RJ, Yan L, Richardson N, Dong SL, Ellis MA, Zhang Y, He YL, Chen H, Oiao BC and Ma BL. 2009. Active tectonics and surface rupture of the Pengxian-Guanxian fault, Longmen Mountain, Sichuan, China. Quaternary Sciences, 29(3): 403-415 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Liu-Zeng J, Zhang Z, Wen L, Tapponnier P, Sun J, Xing X, Hu G, Xu Q, Zeng L, Ding L, Ji C, Hudnut KW and Van der Woerd J. 2009. Co-seismic ruptures of the 12 May 2008, Ms 8.0 Wenchuan earthquake, Sichuan: East-west crustal shortening on oblique, parallel thrusts along the eastern edge of Tibet. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 286(3-4): 355-370 DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.017 |

Lockner DA, Morrow C, Moore D and Hickman S. 2011. Low strength of deep San Andreas Fault gouge from SAFOD core. Nature, 472(7341): 82-85 DOI:10.1038/nature09927 |

Ma BQ, Su G, Hou ZH and Shu SB. 2005. Late quaternary slip rate in the central part of the Longmenshan fault zone from terrace deformation along the Minjiang River. Seismology and Geology, 27(2): 234-242 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Mariniere J, Nocquet J M, Beauval C, Champenois J, Audin L, Alvarado A, Baize S and Socquet A. 2020. Geodetic evidence for shallow creep along the Quito fault, Ecuador. Geophysical Journal International, 220(3): 2039-2055 DOI:10.1093/gji/ggz564 |

Maurer J and Johnson K. 2014. Fault coupling and potential for earthquakes on the creeping section of the central San Andreas Fault. Journal of Geophysical Research, 119(5): 4414-4428 |

McLaskey GC and Kilgore BD. 2013. Foreshocks during the nucleation of stick-slip instability. Journal of Geophysical Research, 118(6): 2982-2997 |

Mittempergher S, Di Toro G, Gratier JP, Hadizadeh J, Smith SAF and Spiess R. 2011. Evidence of transient increases of fluid pressure in SAFOD phase Ⅲ cores. Geophysical Research Letters, 38(3): L03301 |

Moore DE and Rymer MJ. 2007. Talc-bearing serpentinite and the creeping section of the San Andreas Fault. Nature, 448(7155): 795-797 DOI:10.1038/nature06064 |

Nadeau RM, Foxall W and McEvilly TV. 1995. Clustering and periodic recurrence of microearthquakes on the San Andreas Fault at Parkfield, California. Science, 267(5197): 503-507 DOI:10.1126/science.267.5197.503 |

Niemeijer A, Marone C and Elsworth D. 2010. Fabric induced weakness of tectonic faults. Geophysical Research Letters, 37(3): L03304 |

Noda H and Lapusta N. 2013. Stable creeping fault segments can become destructive as a result of dynamic weakening. Nature, 493(7433): 518-521 DOI:10.1038/nature11703 |

Ohzono M, Sagiya T, Hirahara K, Hashimoto M, Takeuchi A, Hoso Y, Wada Y, Onoue K, Ohya F and Doke R. 2011. Strain accumulation process around the Atotsugawa fault system in the Niigata-Kobe tectonic zone, central Japan. Geophysical Journal International, 184(3): 977-990 DOI:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04876.x |

Ran YK, Chen LC, Chen GH, Yin JH, Chen J, Gong HL, Shi X and Li CX. 2008. Primary analyses of in-situ recurrence of large earthquake along seismogenic fault of the Ms 8.0 Wenchuan earthquake. Seismology and Geology, 30(3): 630-643 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Reinen LA. 2000. Seismic and aseismic slip indicators in serpentinite gouge. Geology, 28(2): 135-138 |

Richard J, Gratier JP, Doan ML, Boullier AM and Renard F. 2014. Rock and mineral transformations in a fault zone leading to permanent creep: Interactions between brittle and viscous mechanisms in the San Andreas Fault. Journal of Geophysical Research, 119(11): 8132-8153 |

Rosenau M, Rudolf M and Oncken O. 2019. Creep on seismogenic faults: Insights from analogue earthquake experiments. EarthArXiv: 10.31223/osf.io/24u5h

|

Schleicher AM, Warr LN and van der Pluijm BA. 2009. On the origin of mixed-layered clay minerals from the San Andreas Fault at 2.5~3km vertical depth (SAFOD drillhole at Parkfield, California). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 157(2): 173-187 DOI:10.1007/s00410-008-0328-7 |

Schleicher AM, van der Pluijm BA and Warr LN. 2010. Nanocoatings of clay and creep of the San Andreas Fault at Parkfield, California. Geology, 38(7): 667-670 DOI:10.1130/G31091.1 |

Scholz CH. 1998. Earthquakes and friction laws. Nature, 391(6662): 37-42 DOI:10.1038/34097 |

Senobari NS and Funning GJ. 2019. Widespread fault creep in the northern San Francisco bay area revealed by multistation cluster detection of repeating earthquakes. Geophysical Research Letters, 46(12): 6425-6434 DOI:10.1029/2019GL082766 |

Sleep NH and Blanpied ML. 1992. Creep, compaction and the weak rheology of major faults. Nature, 359(6397): 687-692 DOI:10.1038/359687a0 |

Steinbrugge KV and Zacher EG. 1960. Fault creep and property damage, in 'Creep on the San Andreas Fault'. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 50(3): 389-396 |

Tapponnier P, Xu ZQ, Roger F, Meyer B, Arnaud N, Wittlinger G and Yang JS. 2001. Oblique stepwise rise and growth of the Tibet Plateau. Science, 294(5547): 1671-1677 DOI:10.1126/science.105978 |

Tembe S, Lockner DA and Wong TF. 2010. Effect of clay content and mineralogy on frictional sliding behavior of simulated gouges: Binary and ternary mixtures of quartz, illite, and montmorillonite. Journal of Geophysical Research, 115(B3): B03416 |

Thomas MY, Avouac JP, Champenois J, Lee JC and Kuo LC. 2014. Spatiotemporal evolution of seismic and aseismic slip on the Longitudinal Valley Fault, Taiwan. Journal of Geophysical Research, 119(6): 5114-5139 |

Titus SJ, DeMets C and Tikoff B. 2006. Thirty-five-year creep rates for the creeping segment of the San Andreas Fault and the effects of the 2004 Parkfield earthquake: Constraints from alignment arrays, continuous global positioning system, and creepmeters. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 96(4B): S250-S268 DOI:10.1785/0120050811 |

Wang EQ, Kirby E, Furlong KP, Van Soest M, Xu G, Shi X, Kamp PJJ and Hodges KV. 2012. Two-phase growth of high topography in eastern Tibet during the Cenozoic. Nature Geoscience, 5(9): 640-645 DOI:10.1038/ngeo1538 |

Wang H, Li HB, Janssen C, Sun ZM and Si JL. 2015. Multiple generations of pseudotachylyte in the Wenchuan fault zone and their implications for coseismic weakening. Journal of Structural Geology, 74: 159-171 DOI:10.1016/j.jsg.2015.03.007 |

Wang H, Li HB, Si JL, Zhang L and Sun ZM. 2019. Geochemical features of the pseudotachylytes in the Longmen Shan thrust belt, eastern Tibet. Quaternary International, 514: 173-185 DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2018.12.030 |

Xu XW, Wen XZ, Ye JQ, Ma BQ, Chen J, Zhou RJ, He HL, Tian QJ, He YL, Wang ZC, Sun ZM, Feng XJ, Yu GH, Chen LC, Chen GH, Yu SE, Ran YK, Li XG, Li CX and An YF. 2008. The Ms 8.0 Wenchuan earthquake surface ruptures and its seismogenic structure. Seismology and Geology, 30(3): 597-629 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Xu XW, Wen XZ, Yu GH, Chen GH, Klinger Y, Hubbard J and Shaw JH. 2009. Coseismic reverse-and oblique-slip surface faulting generated by the 2008 Mw 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake, China. Geology, 37(6): 515-518 DOI:10.1130/G25462A.1 |

Xu ZQ, Li HQ, Hou LW, Fu XF, Chen W, Zeng LS, Cai ZH and Chen FY. 2007. Uplift of the Longmen-Jinping orogenic belt along the eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: Large-scale detachment faulting and extrusion mechanism. Geological Bulletin of China, 26(10): 1262-1276 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Xu ZQ, Wu ZL, Li HB and Li L. 2018. The most rapid respond to a large earthquake: The Wenchuan Earthquake Fault Scientific Drilling Project. Chinese Journal of Geophysics, 61(5): 1666-1679 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Yang XS, Yang Y and Chen JY. 2014. Pressure dependence of density, porosity, compressional wave velocity of fault rocks from the ruptures of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, China. Tectonophysics, 619-620: 133-142 DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2013.09.012 |

Zhang L, Sun ZM, Li HB, Zhao LS, Song SR, Chou YM, Cao Y, Ye XZ, Wang H and He XL. 2017. Rock record and magnetic response to large earthquakes within Wenchuan Earthquake Fault Scientific Drilling cores. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 18(5): 1889-1906 DOI:10.1002/2017GC006822 |

Zhang PZ, Molnar P and Xu XW. 2007. Late Quaternary and present day rates of slip along the Altyn Tagh Fault, northern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. Tectonics, 26(5): TC5010 |

Zhang PZ, Wen XZ, Shen ZK and Chen JH. 2010. Oblique, high-angle, listric-reverse faulting and associated development of strain: The Wenchuan earthquake of May 12, 2008, Sichuan, China. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 38: 353-382 DOI:10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152602 |

Zheng C, Ding ZF, Zhou XF, Ye QD and Lü MM. 2015. Detection and analysis of repeating earthquakes in Guanxian-Anxian fault by using waveform cross-correlation. Acta Seismologica Sinica, 37(2): 299-311 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

Zubtsov S, Renard F, Gratier JP, Guiguet R, Dysthe DK and Traskine V. 2004. Experimental pressure solution compaction of synthetic halite/calcite aggregates. Tectonophysics, 385(1-4): 45-57 DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2004.04.016 |

陈立春, 冉勇康, 陈杰, 王虎, 史翔, 刘进峰, 董少鹏. 2009. 龙门山前山断裂大地震原地重复发生的地质地貌证据. 第四纪研究, 29(3): 472-483. |

邓起东, 陈社发, 赵小麟. 1994. 龙门山及其邻区的构造和地震活动及动力学. 地震地质, 16(4): 389-403. |

付碧宏, 时丕龙, 张之武. 2008. 四川汶川Ms 8.0大地震地表破裂带的遥感影像解析. 地质学报, 82(12): 1679-1687. |

靳志同, 万永革, 王福昌, 杨帆, 李瑶. 2019. 2008年汶川地震破裂向东北传播的应力作用证据. 大地测量与地球动力学, 39(8): 783-789. |

李海兵, 付小方, Van der Woerd J, 司家亮, 王宗秀, 侯立玮, 邱祝礼, 李宁, 吴富峣, 许志琴, Tapponnier P. 2008. 汶川地震(Ms 8.0)地表破裂及其同震右旋斜向逆冲作用. 地质学报, 82(12): 1623-1643. |

李海兵, 司家亮, 裴军令, 付小方, 王宗秀, 李宁, 侯立玮, 吴富峣, 潘家伟. 2010. 汶川地震(Ms8.0)地表破裂过程探讨. 第四纪研究, 30(4): 677-698. |

李海兵, 许志琴, 王焕, 张蕾, 何祥丽, 司家亮, 孙知明. 2018. 汶川地震断裂带滑移行为、物理性质及其大地震活动性――来自汶川地震断裂带科学钻探的证据. 地球物理学报, 61(5): 1680-1697. |

李勇, 黄润秋, Densmore AL, 周荣军, 闫亮, Richardson N, 董顺利, Ellis MA, 张毅, 何玉林, 陈浩, 乔宝成, 马博琳. 2009. 龙门山彭县-灌县断裂的活动构造与地表破裂. 第四纪研究, 29(3): 403-415. |

马保起, 苏刚, 侯治华, 舒赛兵. 2005. 利用岷江阶地的变形估算龙门山断裂带中段晚第四纪滑动速率. 地震地质, 27(2): 234-242. |

冉勇康, 陈立春, 陈桂华, 尹金辉, 陈杰, 宫会玲, 史翔, 李陈侠. 2008. 汶川Ms 8.0地震发震断裂大地震原地重复现象初析. 地震地质, 30(3): 630-643. |

徐锡伟, 闻学泽, 叶建青, 马保起, 陈杰, 周荣军, 何宏林, 田勤俭, 何玉林, 王志才, 孙昭民, 冯希杰, 于贵华, 陈立春, 陈桂华, 于慎鄂, 冉勇康, 李细光, 李陈侠, 安艳芬. 2008. 汶川Ms 8.0地震地表破裂带及其发震构造. 地震地质, 30(3): 597-629. |

许志琴, 李化启, 侯立炜, 付小芳, 陈文, 曾令森, 蔡志慧, 陈方远. 2007. 青藏高原东缘龙门山-锦屏造山带的崛起――大型拆离断层和挤出机制. 地质通报, 26(10): 1262-1276. |

许志琴, 吴忠良, 李海兵, 李丽. 2018. 世界上最快回应大地震的汶川地震断裂带科学钻探. 地球物理学报, 61(5): 1666-1679. |

郑晨, 丁志峰, 周晓峰, 叶庆东, 吕苗苗. 2015. 利用波形互相关方法识别分析灌县-安县断裂重复地震. 地震学报, 37(2): 299-311. |

2020, Vol. 36

2020, Vol. 36