2. 北京大学电子显微镜实验室, 北京 100871

2. Electron Microscopy Laboratory of Peking University, Beijing 100871, China

俯冲带水的问题一直是一个热点问题,它是壳幔水循环的窗口。水影响着地幔的电导率、扩散率、流变学特征、熔体的行为以及地震波速率,对地幔动力学过程有重要意义。大洋俯冲板片进入俯冲带,沉积物中的游离水以及岩石中含水矿物如角闪石、帘石、硬绿泥石等在俯冲带浅部发生脱水(小于20km);蓝闪石脱水发生在硬柱石蓝片岩向硬柱石榴辉岩转变过程中,深度约为60~70km(魏春景和张颖慧,2008);而蛇纹石脱水发生在120~180km的深度(Ulmer and Trommsdorff, 1995; Wunder and Schreyer, 1997),是引起地幔楔发生部分熔融产生岛弧岩浆以及触发深源地震的重要原因(Scambelluri et al., 1995; Hattori and Guillot, 2007; Kawakatsu and Watada, 2007; 魏春景和张颖慧,2008)。蛇纹石化是大洋底变质作用的一个普遍过程,据统计,占大西洋洋壳面积5%~25%的洋壳发生了蛇纹石化(Cannat et al., 1995,2010; Carlson,2001; Mével,2003; Deschamps et al., 2013)。蛇纹石化可能发生在大洋中脊拉张环境、岛弧聚敛环境和绿岩带环境(李旭平等,2003)。大洋板块俯冲前缘海沟附近,由于板片发生弯折,产生大量深断裂(深达20km)(Ranero et al., 2003),海水贯通其中,也易发生大规模蛇纹石化作用。另外,俯冲上板片悬浮地幔楔在俯冲带流体作用下也可发生蛇纹石化作用(Fyfe and McBirney, 1975; Hyndman and Peacock, 2003)。蛇纹岩在俯冲板片脱水过程中起着至关重要的作用,是俯冲带流体的重要来源。另外,蛇纹岩脱水过程带动流体活动性元素如B、Li、Cl、As、Sb、U、Th和Sr等在地壳与地幔尺度内循环(Hattori and Guillot, 2003; Hilairet et al., 2007; Deschamps et al., 2013; Harvey et al., 2014; Scambelluri et al., 2014,2015; Green and Falloon, 2015)。

俯冲带蛇纹岩既然如此重要,研究其在俯冲带中的变质演化过程就具有重要意义。国内外学者在这方面做过很多研究,取得了重要进展。本文将结合中国西南天山蛇纹岩的研究实例和世界上发现的其他地区的高压蛇纹岩类型,阐述俯冲带蛇纹岩的变质过程以及确定变质蛇纹岩的温压条件的可用方法。文中未注明矿物的缩写据Whitney and Evans(2010)。

2 俯冲带蛇纹岩的变质过程

近几十年来,地质学家对变基性岩、变泥质岩进行了深入研究,利用相平衡模拟与岩石学相结合的方法,获得了全岩体系下这类岩石的变质演化过程,而且成功再现了特定成分岩石中所记录的P-T轨迹(如Wei and Powell, 2003,2005; Wei and Clarke, 2011)。利用岩石中的特征矿物组合、矿物温压计以及特征矿物(如石榴石)的成分环带相结合的方法即可获得岩石的温压条件以及变质P-T轨迹。然而,蛇纹岩的矿物组合简单,除了主要矿物蛇纹石类,通常很少发育其他变质矿物。而高压叶蛇纹石对温压不敏感,可以稳定到50kbar以上(Ulmer and Trommsdorff, 1995; Wunder and Schreyer, 1997),这就给确定蛇纹

岩的温压条件带来了困难。但是,近几十年来,研究者们通过实验岩石学与天然样品相结合的方法,在这方面有了重要进展。

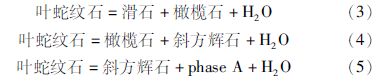

大洋底变质作用过程中,洋壳橄榄岩和辉石岩在海水作用下发生蛇纹石化作用转变成蛇纹岩,发生的反应为:

因此,蛇纹石化作用常伴随着脱Ca和脱H2的过程。与橄榄岩等超基性岩共生或者伴生的基性岩等常在蛇纹石化作用的同时发生钙化作用,形成异剥钙榴岩。纯蛇纹岩含有大约13%的水,主要由蛇纹石矿物组成,次要矿物有磁铁矿、菱镁矿、绿泥石、氢氧镁石、角闪石、滑石等。很多弱蛇纹石化的超基性岩中还保留着橄榄石、斜方辉石、单斜辉石和尖晶石等的残晶。

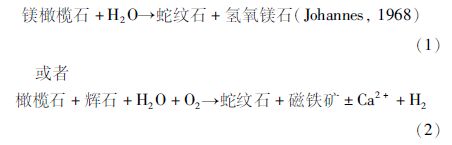

自然界中最常见的蛇纹石矿物主要有三种:纤蛇纹石、利蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石(图 1)。它们形成的地质环境不同,具有不同的物理结构和化学成分。由于颗粒细小,通常在显微镜下较难区分,但是它们具有不同的Raman光谱谱峰,通过Raman光谱仪可以很好的区分它们(图 1)。MSH(MgO-SiO2-H2O)体系下纤蛇纹石和利蛇纹石具有相同的化学通式Mg6Si4O10(OH)8却结构不同,纤蛇纹石为管状结构,利蛇纹石为片状结构。纤蛇纹石和利蛇纹石为低温低压稳定的产物,通常出现于250℃以下,压力较低的环境中,如水分充足的大洋底变质过程中。静压力条件下,纤蛇纹石和利蛇纹石交代原生橄榄石、辉石等形成绢石结构,保留原生矿物的假象或交代橄榄石形成网眼结构。通常纤蛇纹石充填于脉体中,形成梳状结构(图 1)。现代大西洋洋底捕捞的洋底蛇纹岩主要由利蛇纹石和纤蛇纹石组成(Aumento and Loubat, 1971; Christensen,1972; Isabel et al., 2008)。纤蛇纹石和利蛇纹石具有稳定的晶胞参数值,分别为a=5.32Å,b=9.2Å,c=14.64Å,β=90°和a=5.336Å,b=5.336Å,c=7.239Å,β=93.33°(Strunz,1970)。叶蛇纹石为高压状态下稳定的蛇纹石种类,俯冲带中随着温压升高可由利蛇纹石或纤蛇纹石转变而来,呈叶片状,颗粒较为粗大(图 1)。MSH体系下叶蛇纹石的化学通式为Mg3m-3Si2mO5m(OH)4m-6(m为单位晶胞内硅氧四面体的个数)(Kunze,1961; Mellini et al., 1987),与纤蛇纹石和利蛇纹石相比,叶蛇纹石相对富Si。晶体结构为特殊的交替波状结构(图 1,Mellini et al., 1987; Wunder et al., 2001),当m=17时,a=43.505(6)Å,b=9.251(1)Å,c=7.263(1)Å,β=91.32(1)°(Capitani and Mellini, 2004),此时温度约为435℃(Mellini et al., 1987)。其晶胞参数a为不定值,随着温度压力变化,通常在33~50Å之间变化(Mellini et al., 1987),也有报道高达109Å的(Zussman et al., 1957),但是低于33Å不太可能(Mellini and Zussman, 1986)。

| 图 1 三种蛇纹石(纤蛇纹石、利蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石)的晶体结构和晶体形态、标准拉曼谱峰和显微镜图片 [1]纤蛇纹石,利蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石的标准Raman谱峰数据引自Rinaudo et al.(2003);[2]该图片据Evans et al.(2013)修改;[3]该图片据Rinaudo et al.(2003)修改;[4]该图片据Groppo et al.(2006)修改;[5]叶蛇纹石的晶体结构引自Wunder et al.(2001) Fig. 1 Three kinds of serpentines(chrysotile,lizardite and antigorite)with their crystal structures,st and ard Raman spectra and micrographs are shown [1] the st and ard Raman spectra of chrysotile,lizardite and antigorite are quoted from Rinaudo et al.(2003); [2] the micrograph is modified after Evans et al.(2013); [3] the micrograph is modified after Rinaudo et al.(2003); [4] the micrograph is modified after Groppo et al.(2006); [5] the crystal structure of antigorite is quoted from Wunder et al.(2001) |

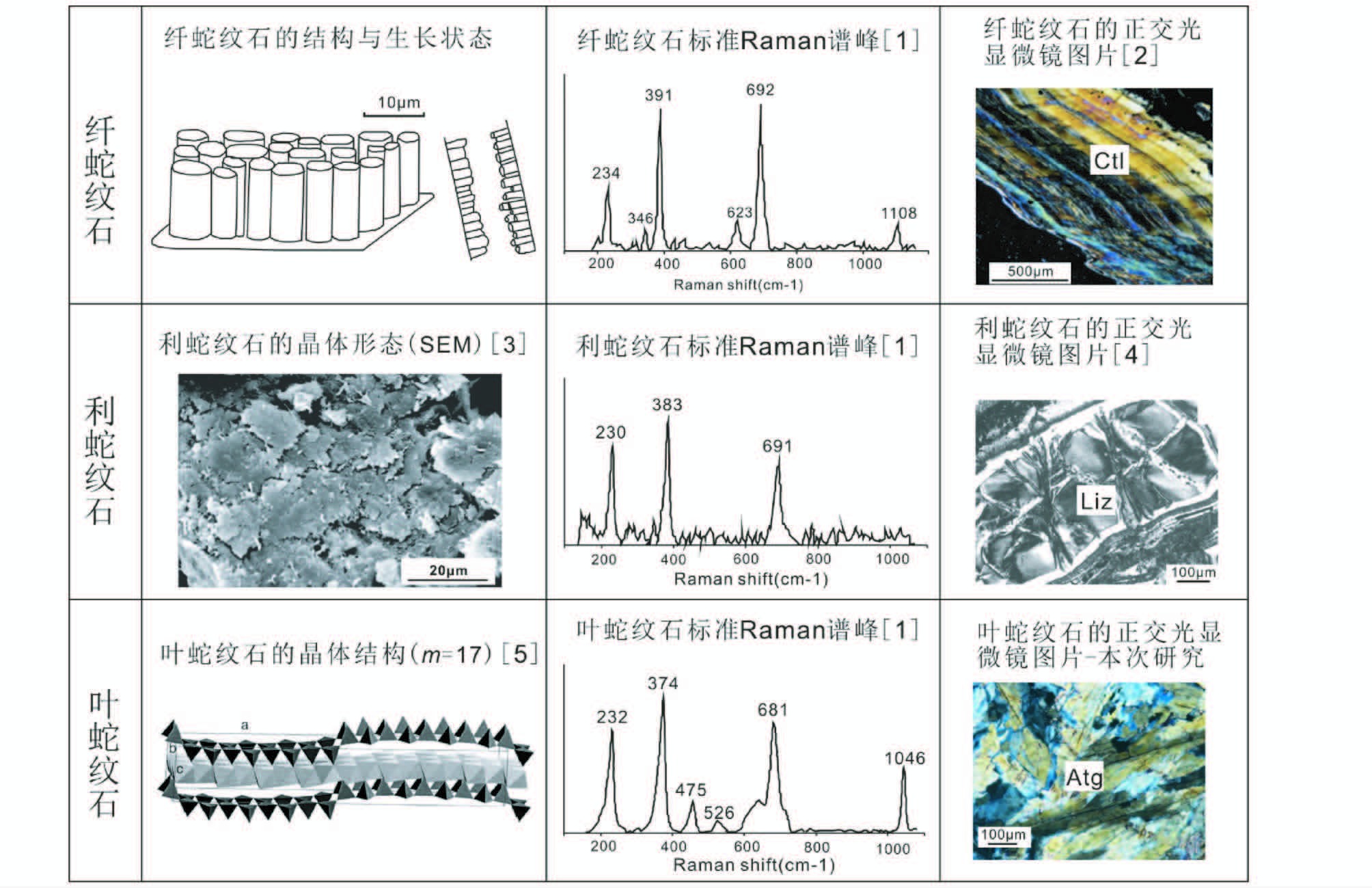

利蛇纹石和纤蛇纹石稳定于低温低压条件下,最新的研究基于第一性原理计算得到利蛇纹石在温度低于250℃,且压力低于25kbar的条件下稳定(Ghaderi et al., 2015; 图 2)。如图 2,随着温压升高利蛇纹石转变成叶蛇纹石+氢氧镁石矿物组合。Hanley and Wicks(1995)观察Cassiar(British Columbia)区的纤蛇纹石矿床发现,利蛇纹石和纤蛇纹石之间也存在转变关系,在大约250±50℃,压力低于1kbar条件下,利蛇纹石被纤蛇纹石+叶蛇纹石组合替代。而利蛇纹石的稳定域还与其Al含量相关,Al含量越高,稳定温度越高(Caruso and Chernosky, 1979;O’Hanley et al., 1989)。

| 图 2 蛇纹石的稳定范围(据Ghaderi et al., 2015) 紫色粗实线为利蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石的理论相边界(Ghaderi et al., 2015);紫色虚线为基于实验结果调整得到的利蛇纹石的稳定域(Ghaderi et al., 2015);黄色区域代表冷俯冲带的地温梯度(NE Japan,lzu-Bonin-Marianas和Tonga);灰色区域为利蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石的相边界(Evans,2004);阴影区域为Schwartz et al.(2013)根据岩石学观察确定的利蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石的相边界;①、②、③、④、⑤分别代表不同研究者确定的叶蛇纹石的稳定域:①红色粗实线(Ulmer and Trommsdorff, 1995);②绿色粗实线(Wunder and Schreyer, 1997);③浅绿色粗实线(Bose and Navrotsky, 1998);④橘色粗实线(Bromiley and Pawley, 2003);⑤蓝色粗实线(Hilairet et al., 2006; Nestola et al., 2010);灰色虚线为无水条件下叶蛇纹石的脱水边界(Perrillat et al., 2005). Liz-利蛇纹石;Atg-叶蛇纹石;Brc-氢氧镁石;phA-phase A;En-顽火辉石;Ol-橄榄石;Tlc-滑石 Fig. 2 Stability field of serpentines(after Ghaderi et al., 2015) Purple solid curve: theoretical phase boundary between Liz and Atg + Brc assemblage determined by Ghaderi et al.(2015); Purple dashed curve: theoretical phase boundary rescaled to the experimental transition temperature at 0 GPa,while keeping the same functional form(Ghaderi et al., 2015); Yellow area: geotherms of cold subduction zones(NE Japan,Izu-Bonin-Marianas, and Tonga); Grey area: Liz/Atg phase boundary determined by Evans(2004); Hatched area: Liz/Atg phase boundary inferred from petrological observations(Schwartz et al., 2013); ①、②、③、④、⑤represent the stability of antigorite determined by different researchers: ① red solid curve(Ulmer and Trommsdorff, 1995); ② green solid curve(Wunder and Schreyer, 1997); ③ light green solid curve(Bose and Navrotsky, 1998); ④ orange solid curve(Bromiley and Pawley, 2003); ⑤ blue solid curve(Hilairet et al., 2006; Nestola et al., 2010); Dashed grey curve shows the dehydration of antigorite under water absent conditions(Perrillat et al., 2005). Liz-lizardite; Atg-antigorite; Brc-brucite; phA-phase A; En-enstatite; Ol-olivine; Tlc-Talc |

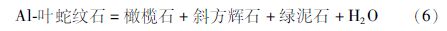

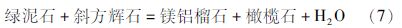

俯冲带中最常见的蛇纹石类型是叶蛇纹石,特别是高压-超高压变质条件下,几乎仅有叶蛇纹石稳定存在。叶蛇纹石的稳定域关系到蛇纹岩的脱水深度,与俯冲带流体、岛弧岩浆作用和深源地震作用密切相关。早期的实验岩石学研究认为MSH体系下高压叶蛇纹石的稳定域取决于三个重要脱水反应(图 2; Ulmer and Trommsdorff, 1995):

这三个反应发生的压力逐一升高。Ulmer and Trommsdorff(1995)的实验压力区间为1~80kbar,选用的叶蛇纹石为天然叶蛇纹石(m=17; Al2O3=1.3%; FeOT=2.59%)。随后,Wunder and Schreyer(1997)同时利用天然叶蛇纹石(m≈17; Al2O3=0.68%; FeOT=1.66%)和合成叶蛇纹石进行实验,压力区间为5~50kbar,认为反应(5)发生的压力在44~55kbar之间,与Ulmer and Trommsdorff(1995)的实验结果相比,脱水曲线往低温低压的方向迁移(图 2)。Bose and Navrotsky(1998)将相平衡实验与矿物的热力学状态方程数据相结合,建立了内部一致性数据库。他们也使用了天然叶蛇纹石(m=?; Al2O3=1.3%; 一些FeO和Fe2O3)进行实验,但是得到的叶蛇纹石脱水曲线与前两组实验有很大的不同,叶蛇纹石脱水发生在50~78kbar,而且50kbar条件下,Bose and Navrotsky(1998)的结果比Wunder and Schreyer(1997)的结果高了近100℃。造成这种不同的原因可能是使用的初始叶蛇纹石的成分和结构不同以及实验方法不同(Wunder and Schreyer, 1997; Mysen et al., 1998)。初始叶蛇纹石的晶胞参数a,即m值的大小影响其P-T稳定域(Wunder et al., 2001);另外,叶蛇纹石中含有Al3+、Cr3+、Fe3+等成分,可能使叶蛇纹石稳定到更高的温度。Ulmer and Trommsdorff(1995)的脱水曲线比Wunder and Schreyer(1997)的脱水曲线在更高温域,正是因为其中含有较高Al和Fe。富Al的叶蛇纹石发生分解时,会产生绿泥石矿物

基于这样的认识,Bromiley and Pawley(2003)使用含Al(Al2O3=3.06%)和不含Al的天然叶蛇纹石(m=17)进行高压实验,分别得到了叶蛇纹石在MSH和MASH(MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O)体系下的分解曲线(图 2),发生的脱水反应分别是反应(4)和反应(6),而且当压力>58kbar,温度高于650℃时,有新反应发生产生了镁铝榴石,叶蛇纹石中的Al又转移到了镁铝榴石中:

反应(7)中绿泥石发生脱水作用,产生石榴石橄榄岩,该反应在天然岩石(Scambelluri et al., 2014)和实验中(Shen et al., 2015)都有报道,是岛弧深度的一个重要反应,对岛弧岩浆作用也有重要贡献(Scambelluri et al., 2014)。

综上发现,使用不同的叶蛇纹石进行实验,得到的脱水曲线不同,也有研究者认为最有效的方法是得到叶蛇纹石的状态方程,才能确定有效的叶蛇纹石的稳定域。Hilairet et al.(2006)和Nestola et al.(2010)分别使用天然叶蛇纹石(m=14; Al2O3=3.45%)和(m=17; Al2O3=3.5%~4.0%)进行实验得到叶蛇纹石的热力学数据,计算得到叶蛇纹石水饱和状态下的理想稳定域(图 2)。也有研究者研究叶蛇纹石在水缺失状态下的分解曲线,发现其在大约500℃即发生了脱水分解产生了橄榄石+斜方辉石组合,比在水饱和状态下降低了50~100℃(图 2; Perrillat et al., 2005)。总结这些实验结果,不难看出叶蛇纹石的Al含量对其稳定域有非常大的影响。最近,Padrón-Navarta et al.(2013)提出了FMASH(FeO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O)体系下叶蛇纹石的理想Tschermak(Al2Mg-1Si-1)模型,该模型很好的适用于FMASH体系的实验结果。虽然蛇纹岩的常见矿物组合叶蛇纹石+橄榄石+绿泥石+流体可以在一个很宽的温压范围内稳定,但是当叶蛇纹石与绿泥石达到平衡时,叶蛇纹石的Al含量对温度特别敏感,因此叶蛇纹石的Al可以作为温度计来使用(Padrón-Navarta et al., 2013)。进行相平衡计算时,在视剖面图中不同稳定域叶蛇纹石的Al等值线为近平行压力轴分布,可以很好的界定温度范围(Padrón-Navarta et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2015)。

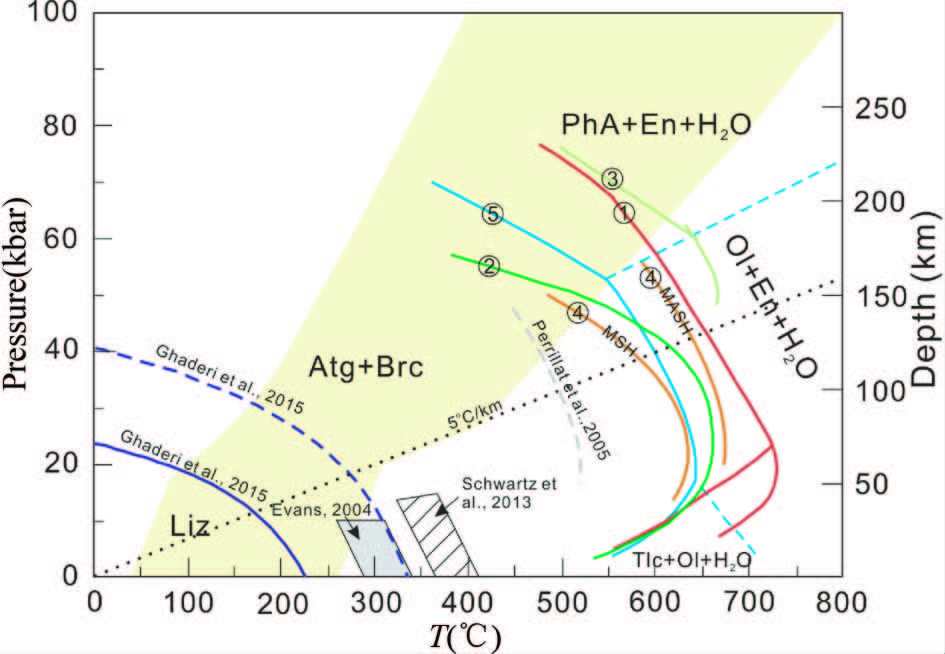

2.2.2 叶蛇纹石的m值叶蛇纹石具有特征的波状结构,a轴方向的四面体个数,即m值随着温度压力变化发生调整,因此其成分(Mg3m-3Si2mO5m(OH)4m-6)和结构不是固定的,而是一个多体系列(Thompson,1978),而且a值不连续变化,对应m值呈整数增长,其成分为不连续的点(Ferraris et al., 1986)。Kunze(1961)认为叶蛇纹石的a值参数可以作为地温计来使用。热力学计算结果表明a轴长的叶蛇纹石稳定于较低温度,而a轴短的叶蛇纹石则稳定于较高温度(Kunze,1961; Trommsdorff,1983)。Mellini et al.(1987)使用TEM方法研究了不同产地、不同变质期次的叶蛇纹石的a轴晶胞参数和m值,发现叶蛇纹石的晶胞参数a确实随着变质级次升高(温度升高)而变短,而且变质级次高的叶蛇纹石结晶度好,其内部的缺陷和位错就少。但是,他们认为叶蛇纹石的晶胞参数a(m值)作为温压计的使用范围是有限的,因为真正的平衡在天然样品中很难达到。Wunder et al.(2001)使用合成的不含Al、Fe的MSH-叶蛇纹石进行系统的高压实验,旨在研究叶蛇纹石的m值与P-T之间是否存在相关关系。实验的P-T条件为350~710℃,2~50kbar。该实验结果显示同一个温压条件下的叶蛇纹石具有不同的m值,表明实验并未真正达到平衡。但是,统计发现叶蛇纹石的m值的峰值随着温度升高而减小,随着压力升高而增大(图 3)。虽然叶蛇纹石的m值不能作为准确的温压计,但是叶蛇纹石的晶胞参数a确实随温度、压力具有一定的变化趋势。自然界中真正的平衡(即叶蛇纹石具有唯一的m值)很难达到,通常同一个样品中的叶蛇纹石具有不同的m值,即使是同一个叶蛇纹石颗粒m值也可能发生变化(Mellini et al., 1987; Wunder et al., 2001),因此不平衡是常态。但是,通过Wunder et al.(2001)的实验方法和结果可得知,大量测试样品的叶蛇纹石的m值,通过统计学方法取得m值的峰值,可以用以指示温压条件。

| 图 3 实验结果显示的叶蛇纹石的m值峰值与温度、压力的关系(据Wunder et al., 2001) 图中的斜点线划分了不同m值的温压区域,其中的斜体数字代表不同m值. 叶蛇纹石的最大稳定域曲线来自Ulmer and Trommsdorff(1995)(红色实线,U&T,95)和Wunder and Schreyer(1997)(绿色实线,W&S,97). 纤蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石的转变线来自Evans et al.(1976)(橘色实线). 蓝色虚线为据Peacock(1990)的模型所确定的一个50Ma的俯冲洋壳经历的理论P-T轨迹 Fig. 3 P,T-dependence of peak m-value of antigorite determined by experimental results(after Wunder et al., 2001) Dotted lines limit P,T ranges for different m-values(labelled by italic numbers). Maximum stability fields of antigorite are shown as determined experimentally by Ulmer and Trommsdorff(1995)(red solid line,U&T,95) and Wunder and Schreyer(1997)(green solid line,W&S,97). The chrysotile to antigorite transformation is taken from Evans et al.(1976)(orange solid line). Blue dashed line represents a theoretical P-T path for the subduction of a 50Ma old oceanic crust as modelled by Peacock(1990) |

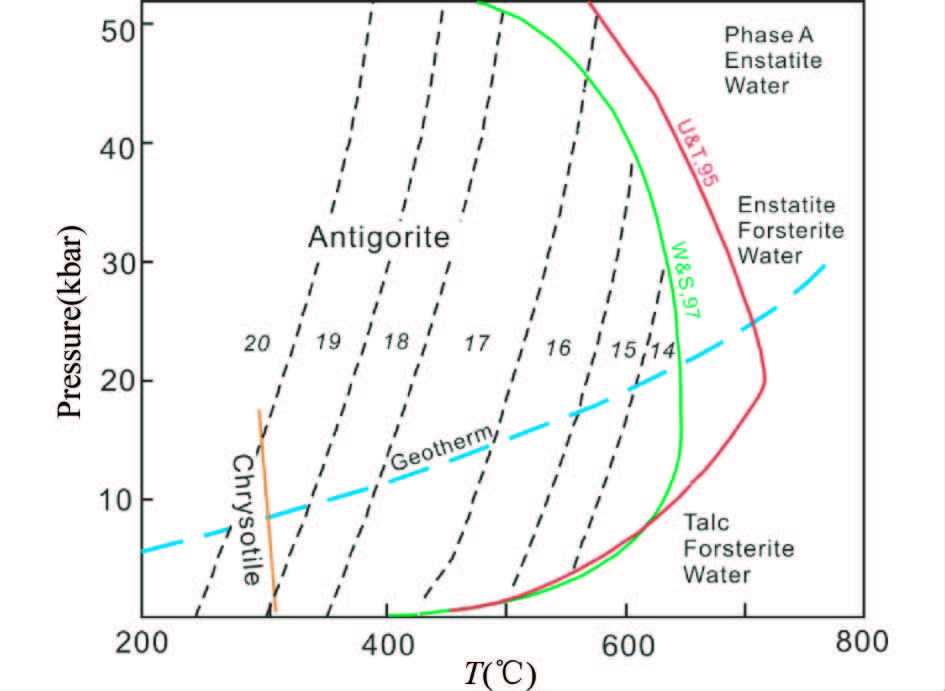

钛斜硅镁石(TiChu; Ti-clinohumite)和钛粒硅镁石(TiChon; Ti-chondrodite)是常在蛇纹岩化超基性岩中出现的次要矿物,它们都属于硅镁石族矿物。这类矿物在岩石中为特征的橘黄色或者红色(图 4),非常容易辨认。硅镁石族矿物的化学通式为:n(M2SiO4)M1-XTiX(OH,F)2-2XO2X [M: Mg,Fe,Mn,Ni,Zn; X<0.5]共有四个不连续端元组分,其中n=1为块硅镁石;n=2为粒硅镁石;n=3为硅镁石;n=4为斜硅镁石。自然界中最常见的是斜硅镁石,而且是含Ti和F的端元,粒硅镁石相对要少一些,而不含Ti和F的纯硅镁石在自然界中尚未发现。硅镁石族矿物的结构由不同含量的橄榄石层(O)与块硅镁石层(N)堆垛而成,其中粒硅镁石为ON,硅镁石为OON,斜硅镁石为OOON(Thompson,1978; Ehlers and Hoinkes, 1987)。硅镁石族矿物结构中存在三种常见的替代结构:FeMg-1,OHF-1和TiO2Mg-1(OH,F)-2,从而具有变化的成分。晶体结构学研究认为含Ti粒硅镁石和Ti斜硅镁石的Ti分布在Mg(OH)O层中(Kocman and Rucklidge, 1973; Fujino and Takéuchi,1978),而不是既存在于橄榄石层又存在于Mg(OH)O层(Robinson et al., 1973)。

| 图 4 西南天山蛇纹岩中钛斜硅镁石(TiChu)颗粒和钛粒硅镁石(TiChon)颗粒的单偏光显微照片 Fig. 4 Photomicrographs(plane-polarized light)of selected Ti-clinohumite(TiChu) and Ti-chondrodite(TiChon)from Chinese southwestern Tianshan serpentinite |

自然界中报道的硅镁石族矿物,特别是斜硅镁石和粒硅镁石,主要是在接触变质或者区域变质的灰岩中(Rice,1977; Franz and Ackerm and ,1980; Kearns et al., 1980; Ehlers and Hoinkes, 1987; Mazzoli et al., 2013),或者是在碳酸盐岩和超基性岩中(McGetchin et al., 1970; Aoki et al., 1976; Trommsdorff and Evans, 1980; Scambelluri et al., 1991; Okay,1994; Rahn and Rahn, 1998; Trommsdorff et al., 2001; Yang,2003; López Sánchez-Vizcaíno et al., 2005,2009)。出现在碳酸盐岩中的硅镁石族矿物多为富F贫Ti的类型(Ehlers and Hoinkes, 1987; Balassone et al., 2002; Mazzoli et al., 2013),而出现在超基性岩中的则多为富Ti贫F的类型(Smith,1977; Dymek et al., 1988; Rahn and Rahn, 1998; López Sánchez-Vizcaíno et al., 2005,2009)。TiChu和TiChon常出现在超基性岩中,而且通常出现在高压-超高压超基性岩中。相比较而言,TiChon出现的频率比TiChu低,而且出现在更高压的岩石类型中。最早报道TiChon和TiChu的共生是在Buell Park Kimberlite(Arizona,USA; Aoki et al., 1976; Smith,1977);随后在3800Ma的Isua Supracrustal Belt蛇纹岩化纯橄岩(western Greenl and ; Dymek et al., 1988)中也报道了TiChon与TiChu互生;在Dabie-Shan超高压带石榴辉石岩中报道了TiChon和TiChu伴生(许志琴等,2003; Hermann et al., 2007);在Beigua unit(Voltri Massif)的富Fe-Ti交代变质辉长岩中(Scambelluri and Rampone, 1999)和Erro-Tobbio unit(Voltri Massif,Ligurian Alps,Italy)的蛇纹岩中(De Hoog et al., 2014)都出现TiChon和TiChu共生;以及最近报道的中国西南天山蛇纹岩中的Tichon和Tichu共生(Shen et al., 2014,2015)。

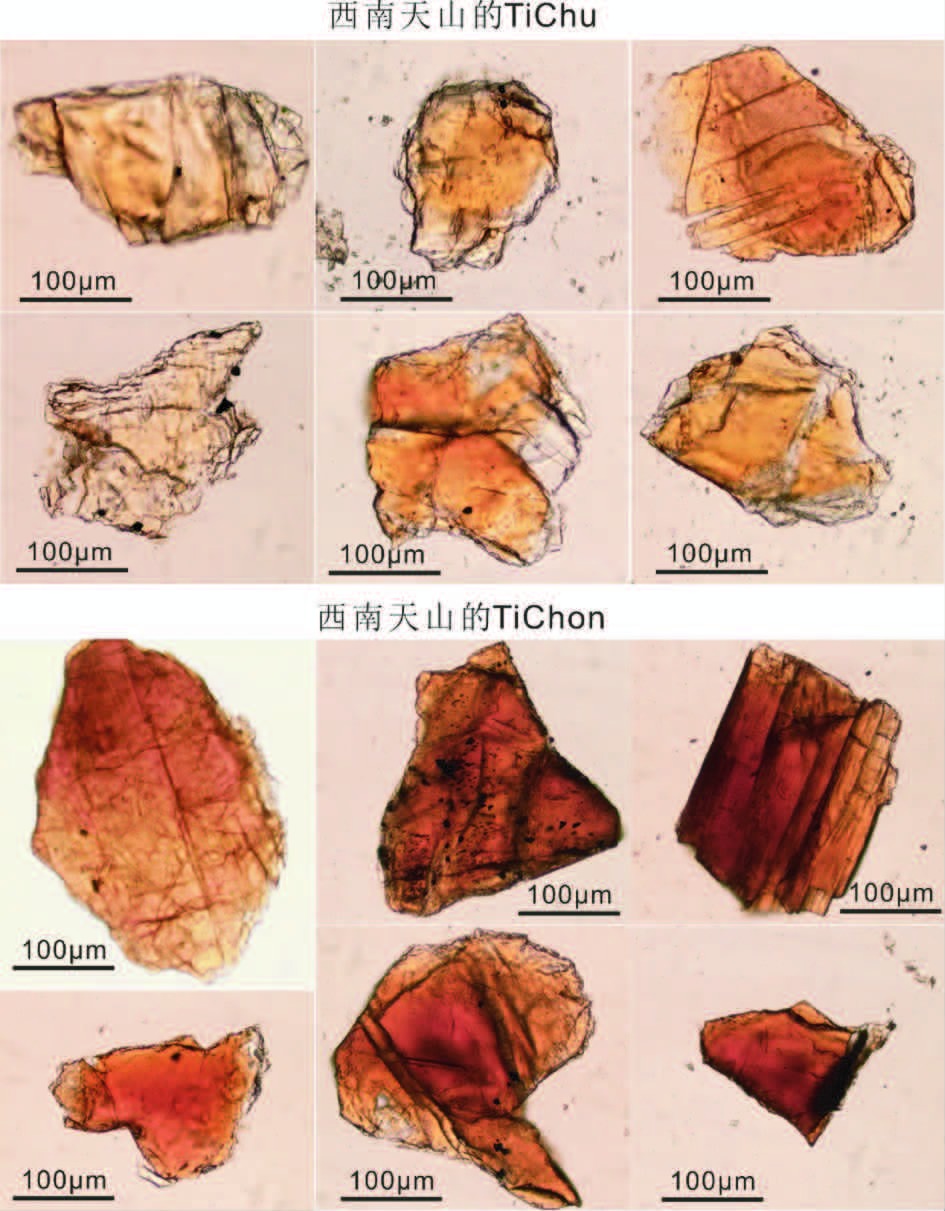

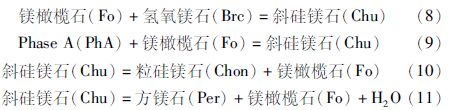

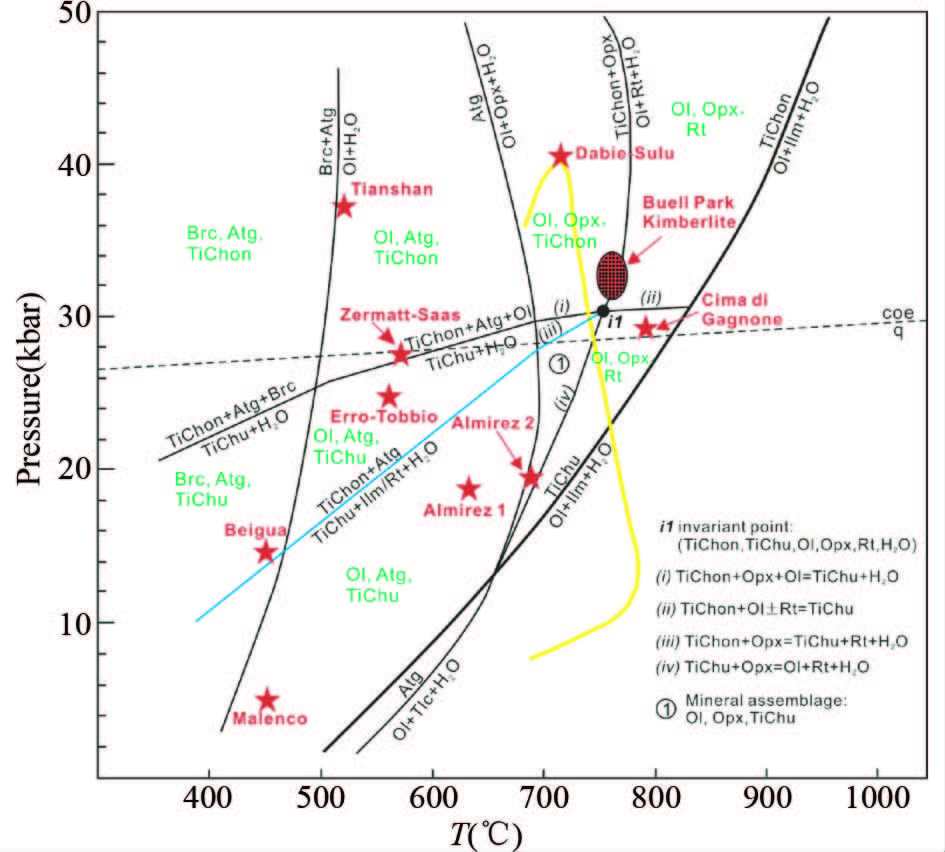

尽管硅镁石族矿物在超基性岩中常见,但是这类矿物的稳定范围是什么,是否对超基性岩的变质作用有指示意义?实验岩石学一直在这方面努力。为了减少参变量,最初的实验研究在MSH体系下进行(图 5a)。含水斜硅镁石(Chu; clinohumite-OH)和含水粒硅镁石(Chon; chondrodite-OH)最早在700~1100℃,29~77kbar的实验条件下合成,而且Chon最初被叫做“phase D”(Yamamoto and Akimoto, 1977)。这次实验虽然得到了一些重要反应的边界,但是本次实验为合成实验,而且反应时间短,并未真正达到平衡,因此得到的反应边界有待商榷(Wunder,1998)。Wunder(1998)采用正反双向实验方法,使用实验室合成的Chu和Chon在500~1100℃,10~100kbar实验条件下研究MSH体系下Chu和Chon的稳定域(图 5a)。Chu的稳定域受制于以下几个反应:

| 图 5 硅镁石族矿物稳定性的实验结果 (a)MSH体系斜硅镁石(Chu)和粒硅镁石(Chon)的稳定域,实验结果来自Yamamoto and Akimoto(1977)和Wunder(1998). 黑色实线代表含钛斜硅镁石(TiChu)的分解反应,实验结果分别来自Engi and Lindsley(1980)(E&L,80)和Weiss(1997)(W,97);(b)全岩体系下(不含F)钛斜硅镁石(TiChu)和钛粒硅镁石(TiChon)稳定性的高压实验结果(据Shen et al., 2015) Fig. 5 Experimental results of the stability of humite-group minerals (a)stability of clinohumite(Chu) and chondrodite(Chon)in MSH system. The experimental results are from Yamamoto and Akimoto(1977) and Wunder(1998). The black solid lines represent the decomposition reaction of Ti-clinohumite(TiChu) and the experimental results are from Engi and Lindsley(1980)(E&L,80) and Weiss(1997)(W,97);(b)stability of Ti-clinohumite(TiChu) and Ti-chondrodite(TiChon)in whole-rock system(F free)constrained by the high-pressure experiments(after Shen et al., 2015) |

Chon的稳定域受制于以下几个反应:

虽然Yamamoto and Akimoto(1977)和Wunder(1998)的实验结果有所偏差,但是由此可知MSH体系下,Chu的稳定压力>15kbar,压力上限并没有很好的确定,可能高达100kbar,稳定温度为600~1100℃;Chon的稳定压力比Chu高,为>20kbar,可能达到100kbar以上,稳定温度为700~1100℃(图 5a)。

考虑到自然界产出的实际情况,Ti或F的加入可能会影响硅镁石族矿物的稳定性。Engi and Lindsley(1980)使用天然TiChu(TiO2=5%~5.6%; Malenco)在400~800℃,1~24kbar的条件下进行分解反应:

结果显示,TiChu在低温条件(<750℃)下地壳深度(<10kbar)即可发生分解。同样,Weiss(1997)也使用天然TiChu(XTi=0.46)进行实验限制分解反应(14),并将压力做到了60kbar,得到的实验结果与Engi and Lindsley(1980)相似,但在低压部分的分解压力要高一些,高压条件下TiChu可以稳定到1000℃(>60kbar)(图 5a)。Ti的加入将Chu的稳定域在P-T图上往低温低压的方向迁移(图 5a),即MSH体系下得到的Chu和Chon的稳定区域并不能代表自然界中产出的TiChu和TiChon,而且实验研究和野外观察都表明F的加入可能使得TiChu稳定到更高温度(Engi and Lindsley, 1980; Weiss,1997; López Sánchez-Vizcaíno et al., 2005,2009; Hermann et al., 2007)。

全岩体系下TiChon和TiChu的稳定性如何,尚缺乏系统的研究。最近,Shen et al.(2015)使用天然TiChon(来自Tianshan)和TiChu(来自Malenco)在全岩体系下(不含F),600~750℃,25~55kbar条件下进行活塞圆筒高压实验,模拟正常地幔超基性岩成分中TiChon和TiChu的稳定性。结果显示TiChon稳定的压力确实比TiChu高,压力高于26kbar(550℃)时,TiChon由TiChu反应生成,而且温度越高,生成TiChon的压力也越高(图 5b)。压力高于55kbar(700℃),TiChon分解消失。TiChon受温度的影响很大,温度高于750℃,TiChon不稳定而逐渐分解。本次实验并没有很好的限定TiChu的稳定域,因为在600~700℃,25~55kbar之间TiChu均存在。虽然不排除有亚稳定存在的可能性,但是没有观察到TiChu消失。25kbar,750℃,TiChu发生分解反应生成了橄榄石和金红石:

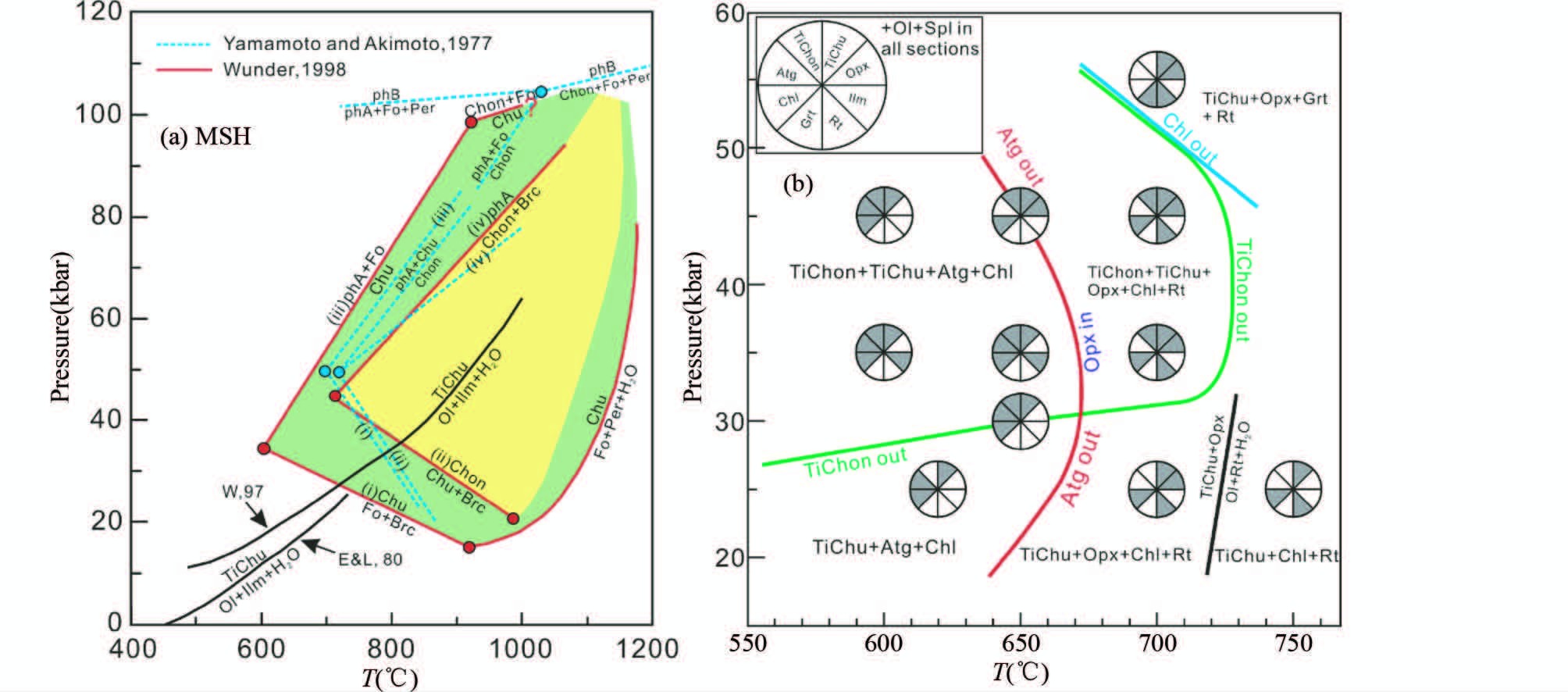

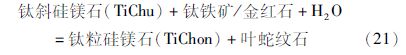

到目前为止,超基性岩含Ti体系的相平衡计算还不能进行,因为目前的常用数据库中都缺乏TiChon和TiChu的数据模型。Shen et al.(2015)根据高压实验结果和Schreinemaker法则确立了正常组分蛇纹岩(由正常地幔组分橄榄岩转变成的蛇纹岩)的变质演化P-T格子(图 6)。将文献中报道的含TiChu和TiChon的超基性岩投图在该P-T格子上,其矿物组合和温压条件很好的吻合该P-T格子(图 6; Shen et al., 2015)。

| 图 6 基于实验结果和Schreinemaker’s法则得到的TiChu和TiChon在超基性岩中的P-T格子(据Shen et al., 2015) 变质反应和矿物组合都标注在图上. 红色五角星代表世界上报道的TiChon/TiChu出露区的峰期温压条件;黄色曲线代表大别山地区石榴辉石岩的P-T轨迹;蓝色曲线表示富Ti超基性岩中发生的反应 Fig. 6 P-T grid for TiChu and TiChon in ultramafic rocks based on experimental results and Schreinemaker’s rule(after Shen et al., 2015) Metamorphic reactions and mineral assemblages are shown in the diagram. Red filled stars represent the peak conditions of TiChu-TiChon bearing rocks from all over the world; yellow curve represents the P-T path of garnet pyroxenes from Dabie-Shan; blue curve represents the reaction occur in Ti-rich ultramafic rocks |

TiChu的稳定压力下限尚不可知,但是由Malenco蛇纹岩的温压条件为450℃,5kbar(Trommsdorff and Evans, 1980)可知,TiChu在低压条件下也可稳定。TiChu在高温下不稳定,发生反应(14)生成橄榄石+钛铁矿组合。高压下TiChu转变成TiChon,在不同温度条件下,发生不同反应:

蛇纹岩对温度更加敏感,低温下叶蛇纹石和氢氧镁石稳定,高温下发生氢氧镁石脱水反应和叶蛇纹石脱水反应,蛇纹岩逐渐转变成橄榄岩,自然界已有这方面的实例:如Cima di Gagnone的石榴二辉橄榄岩(Alps; Evans and Trommsdorff, 1978),Cerro del Almirez的含绿泥石方辉橄榄岩(Spain; Trommsdorff et al., 1998; Padrón-Navarta et al., 2011)等。TiChon+Opx矿物组合稳定温度不能超过750~800℃,而且通常情况下,岩石矿物组合中Opx的含量比TiChon含量高,因此TiChon会在到达完全分解反应:

之前消失。因此,高温条件下TiChon很难稳定存在。由该P-T格子可以看出,正常成分蛇纹岩中出现TiChon为高压-超高压的标志。TiChon的出现不仅与温压条件相关,而且与全岩中的Ti含量密切相关,全岩中的Ti含量越低,出现TiChon所需的压力也越高。特别指出的是,当岩石富Ti,特别是有钛铁矿/金红石存在时,即使在低压条件下也会生长TiChon:

如Beigua Unit(Voltri Massif)的富Fe-Ti交代变质辉长岩中的TiChon(Scambelluri and Rampone, 1999)。

3 西南天山蛇纹岩的变质P-T轨迹和叶蛇纹石的m值西南天山蛇纹岩的变质演化过程,Shen et al.(2015)已经做了详细的论述。西南天山蛇纹岩以透镜体出露于天山超高压变质带的变质泥质岩——石榴云母片岩中。蛇纹岩中还包裹超高压榴辉岩(未发表数据)和异剥钙榴岩。蛇纹岩中尖晶石包裹体中残余的原生矿物可以推测原生橄榄岩的矿物组合;蛇纹岩中大量异剥钙榴岩脉体和蛇纹岩中的利蛇纹石残余表明曾经发生过广泛的大洋底变质作用;TiChon的出现表征经历过超高压变质作用;岩石中TiChon分解产生TiChu的现象又表明后期退变作用的发生。Shen et al.(2015)根据蛇纹化异剥橄榄岩中叶蛇纹石的Al等值线在P-T相图上的投点,结合矿物组合和TiChon/TiChu的稳定性得到其变质峰期的温压条件不低于520±10℃,37±7kbar,经历了复杂的5阶段的变质演化过程(图 7)。西南天山蛇纹岩经历了快速冷俯冲并折返的变质演化过程,已经进入到变质作用的“禁区”——5℃/km地温梯度线以上(Liou et al., 1998),俯冲带中只有俯冲板片在更深处与地幔楔耦合的地温梯度线才能满足这样的温压条件(Syracuse et al., 2010)。

| 图 7 天山蛇纹岩的P-T轨迹(蓝色带箭头的曲线)投在简化的TiChu-TiChon P-T格子上

灰色阴影区为TiChon的稳定区;黄色区域为天山蛇纹岩的峰期温压范围;两条绿色曲线分别代表在80km深度与地幔楔耦合的正常俯冲大洋板片的上表面温度梯度线,和在更深地幔与地幔楔耦合的俯冲大洋板片的上表面温度梯度线(Syracuse et al., 2010);黑色虚线代表 5℃/km地温梯度线

Fig. 7 P-T path of Tianshan serpentinite(blue continuous arrow)on the simplified P-T grid of TiChu-TiChon

Grey area represents the stability field of TiChon; yellow area represents the peak P-T field of Tianshan serpentinite; two green curves represent the top of slab temperatures of a typical subducted oceanic slab fully coupling with the mantle wedge at 80km depth and a subducted slab coupling at greater depth(Syracuse et al., 2010); black dashed line shows the 5℃/km geothermal gradient |

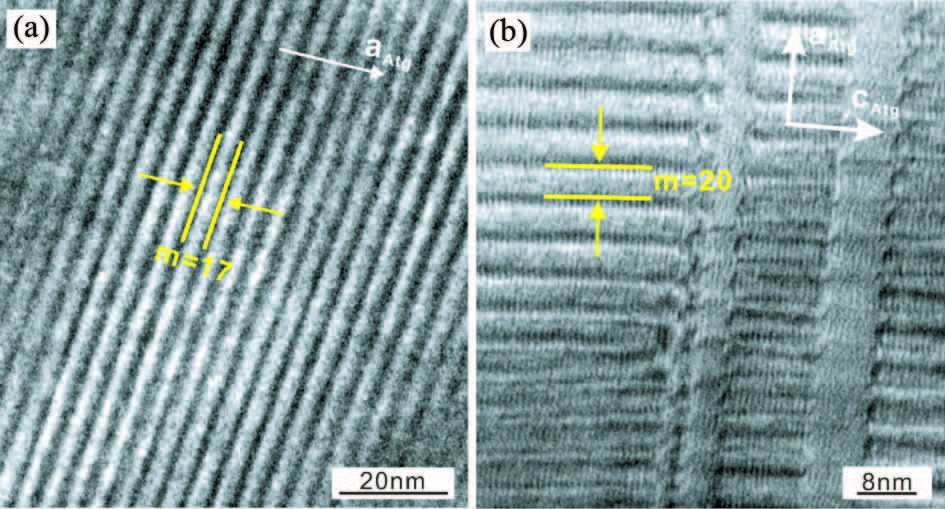

西南天山蛇纹岩经历了超高压变质作用,其主要矿物叶蛇纹石的晶胞参数a或m值是否也记录了这样的过程呢?基于上文对叶蛇纹石m值的论述,我们选取了3个样品C11107 [蛇纹石化异剥橄榄岩;Shen et al.(2015)中选取的计算峰期温压的样品],C107-8(纯蛇纹岩,含有利蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石)和C10728(纯蛇纹岩,仅含有叶蛇纹石),对其中的叶蛇纹石进行透射电子显微镜(TEM)实验测试其m值。

TEM样品的准备采用了两种方法:一种是粉末法,即挑选三个样品中的叶蛇纹石单矿物,将其研磨到200目以下粒度。取少量粉末于丙酮中制成悬浮溶液,用直径2mm的铜网蘸取溶液制成样品;第二种方法是离子减薄法,在薄片中用内径0.8mm的钼环取下要测试的样品,在离子减薄机(加冷台)上将样品减薄至出现适量薄区。TEM实验使用Hitachi H-9000NAR(北京大学电镜中心)仪器,加速电压为100kV。其中样品C11107和样品C107-8都采用了粉末法制样,样品C10728同时采用了两种方法进行制样。

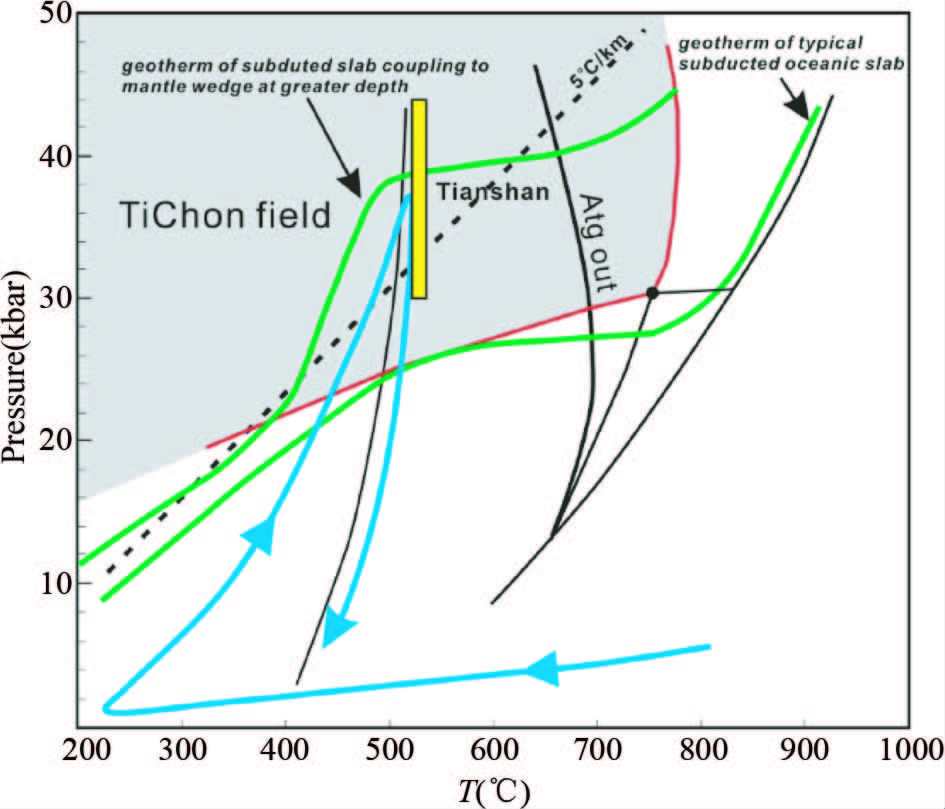

电子显微镜下得到了清晰的叶蛇纹石的晶格条纹(图 8a)。有的颗粒上可以看到两组晶格条纹,a轴和c轴,并伴随着晶格位错(图 8b)。不同样品的叶蛇纹石的m值不同,即使是同一个样品,m值也不同,这说明样品中的叶蛇纹石并没有达到完全的平衡状态,存在不同期次的叶蛇纹石,这与岩相学观察结果是一致的。有的叶蛇纹石颗粒从核部到边部m值由大(m=19)逐渐变小(m=17),这体现了叶蛇纹石从核部到边部的退变过程。

| 图 8 天山蛇纹岩中叶蛇纹石的TEM照片 m值分别为17(a)和20(b),白色箭头代表晶轴方向 Fig. 8 TEM images of antigorite from Tianshan serpentinites m values are 17(a) and 20(b),respectively, and crystal axes are shown(white arrows) |

对得到的实验结果采用统计学的方法,求得样品中叶蛇纹石的m值的峰值(图 9)。样品C11107的峰期温压条件不低于520±10℃,37±7kbar(Shen et al., 2015),其m值的峰值为m=20,因为该样品的温度得到了很好的限定,在此温度条件下,叶蛇纹石m值投在图 3上,记录的压力>50kbar。样品C107-8的矿物组合为叶蛇纹石+磁铁矿+氢氧镁石,含有残余利蛇纹石,叶蛇纹石在利蛇纹石之上生长,温度条件应该在400~500℃之间。该样品的m值的峰值为m=17,几乎达到了叶蛇纹石在常态条件下的m值(Mellini et al., 1987),说明该样品已经退变到了较为低温低压的状态,这与矿物组合代表的温压条件是一致的。样品C10728的矿物组合为叶蛇纹石+磁铁矿+菱镁矿。粉末法和离子减薄法制样得到的m值的统计结果一致,峰值都在m=18。特别指出的是电子显微镜下该叶蛇纹石中含有定向包裹体,包裹体周围的叶蛇纹石的m值无一例外的高达20或以上,笔者推断可能存在某种未知phase,代表更高的压力条件。

| 图 9 不同样品中叶蛇纹石的m值分布图 Fig. 9 Distribution of m value of antigorite from different samples |

蛇纹岩由于成分简单,矿物组合也简单,倘若岩石没有经过流体交代等作用的混染,其成分中通常含有很少的Ca、Al、Na、K等组分,因此在变质过程中参与的变质反应与泥质岩和基性岩相比就少得多。俯冲带蛇纹岩最重要的变质反应是其脱水反应,分为局部脱水和完全脱水。局部脱水由氢氧镁石+叶蛇纹石部分脱水产生橄榄石或角闪石,含Al叶蛇纹石脱水还产生绿泥石矿物;完全脱水即叶蛇纹石分解产生橄榄石+斜方辉石。沿着正常地温梯度俯冲,蛇纹岩都会经历这个过程,通常在大约25kbar,~700℃即发生完全脱水(图 2)。但是,倘若蛇纹岩经历冷俯冲过程,则可以俯冲到深地幔而不发生完全脱水分解(如西南天山蛇纹岩),出现钛粒硅镁石类矿物,叶蛇纹石通过调整自身的m值而稳定到更高压力,甚至在更高压力条件下转变成含水phase,从而将水带到更深的地幔。水是活化地幔的重要组分,金刚石中含水ringwoodite的发现表明410~660km深度的过渡带是富水的(Pearson et al., 2014)。虽然关于水的起源问题尚存在很大争议,但是俯冲带作为壳幔循环的窗口,同时也是水循环的窗口。俯冲带蛇纹岩,特别是冷俯冲的蛇纹岩在这个过程中起着至关重要的作用。对中国西南天山蛇纹岩的研究表明,地球上存在这样的冷俯冲带,蛇纹岩可以发生这样的深俯冲作用,为深部地幔提供大量流体来源。

钛硅镁石类矿物中加入F可以将其稳定性往高温方向提高很多,这已经得到了证实(Engi and Lindsley, 1980; Weiss,1997; López Sánchez-Vizcaíno et al., 2005,2009; Hermann et al., 2007)。自然界中,与壳源物质有关的岩石类型中多为含F的硅镁石类型,如大理岩(Ehlers and Hoinkes, 1987)和大别山石榴辉石岩(Hermann et al., 2007),这使得原岩中含有少量的F,在变质过程中F进入到硅镁石矿物中。西南天山蛇纹岩虽然以透镜体产状出露于变泥质岩中,但是并未受到含F流体的交代,其中的钛硅镁石类为不含F类型(Shen et al., 2014,2015)。含F钛硅镁石可以稳定到叶蛇纹石完全脱水之后,从而将部分水分带到深地幔(Hermann et al., 2007; López Sánchez-Vizcaíno et al., 2009)。

西南天山蛇纹岩叶蛇纹石m值的研究表明,叶蛇纹石的m值记录的压力条件与蛇纹岩矿物组合记录的压力是一致的,其统计值可以用来表征压力条件。确定蛇纹岩温压条件的方法可以总结如下:首先是矿物组合,根据P-T格子(图 6),可以初步推断变质程度。精确获得P-T条件需要进行相平衡计算,利用矿物组合稳定域中的叶蛇纹石的Al等值线可以获得较准确的温度和不太准确的压力。需要注意的是,只有在岩石中存在绿泥石与叶蛇纹石平衡的条件下才可以使用叶蛇纹石等值线。其次,使用岩石中的叶蛇纹石进行TEM测试其m值,并取得m值的统计峰值,结合Al等值线得到的温度,有助于得到更准确的压力值。

目前相平衡模拟尚不能使用含Ti体系,因为数据库中还没有TiChu和TiChon的数据文件,希望在不久的将来我们能够做出所需的TiChu和TiChon的热力学参数,加入到数据库中,从而可以完善相图计算。

致谢 感谢Joerg Hermann教授(澳大利亚国立大学和瑞士伯尔尼大学)对本文思想的重要影响。感谢野外工作中李小犁、彭卫刚等的帮助。感谢Thomas Bader对文章中英文部分的修改。

| [1] | Aoki K, Fujino K and Akaogi M. 1976. Titanochondrodite and titanoclinohumite derived from the upper mantle in the Buell Park Kimberlite, Arizona, USA. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 56(3): 243-253 |

| [2] | Aumento F and Loubat H. 1971. The Mid-atlantic ridge near 45°N. XVI. Serpentinized ultramafic intrusions. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 8(6): 631-663 |

| [3] | Balassone G, Franco E, Mattia CA, Petti C and Puliti R. 2002. Re-examination of fluosiderite, an unknown mineral from southern Italy: Equal to fluorine-rich chondrodite. European Journal of Mineralogy, 14(1): 151-155 |

| [4] | Bose K and Navrotsky A. 1998. Thermochemistry and phase equilibria of hydrous phases in the system MgO-SiO2-H2O: Implications for volatile transport to the mantle. Journal of Geophysical Research, 103(B5): 9713-9719 |

| [5] | Bromiley GD and Pawley AR. 2003. The stability of antigorite in the systems MgO-SiO2-H2O (MSH) and MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O (MASH): The effects of Al3+ substitution on high-pressure stability. American Mineralogist, 88(1): 99-108 |

| [6] | Cannat M, Mével C, Maia M, Deplus C, Durand C, Gente P, Agrinier P, Belarouchi A, Dubuisson G, Humler E and Reynolds J. 1995. Thin crust, ultramafic exposures, and rugged faulting patterns at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (22°-24°N). Geology, 23(1): 49-52 |

| [7] | Cannat M, Fontaine F and Escartín J. 2010. Serpentinization at slow-spreading ridges: Extent and associated hydrogen and methane fluxesat slow spreading ridges. In: Rona PA, Devey CW, Dyment J and Murton J (eds.). Diversity of Hydrothermal Systems on Slow Spreading Ocean Ridges. AGU Geophysical Monograph, Ridges. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union, 188: 241-264 |

| [8] | Capitani G and Mellini M. 2004. The modulated crystal structure of antigorite: The m=17 polysome. American Mineralogist, 89(1): 147-158 |

| [9] | Carlson RL. 2001. The abundance of ultramafic rocks in Atlantic Ocean crust. Geophysical Journal International, 144(1): 37-48 |

| [10] | Caruso LJ and Chernosky JR JV. 1979. The stability of lizardite. The Canadian Mineralogist, 17: 757-769 |

| [11] | Christensen NI. 1972. The abundance of serpentinites in the oceanic crust. Journal of Geology, 80(6): 709-719 |

| [12] | De Hoog JCM, Hattori K and Jung H. 2014. Titanium- and water-rich metamorphic olivine in high-pressure serpentinites from the Voltri Massif (Ligurian Alps, Italy): Evidence for deep subduction of high-field strength and fluid-mobile elements. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 167(3): 990 |

| [13] | Deschamps F, Godard M, Guillot S and Hattori K. 2013. Geochemistry of subduction zone serpentinites: A review. Lithos, 178: 96-127 |

| [14] | Dymek RF, Boak JL and Brothers SC. 1988. Titanian chondrodite- and titanian clinohumite-bearing metadunite from the 3800Ma Isua supracrustal belt, West Greenland: Chemistry, petrology and origin. American Mineralogist, 73(5-6): 547-558 |

| [15] | Ehlers K and Hoinkes G. 1987. Titanian chondrodite and clinohumite in marbles from the Ötztal crystalline basement. Mineralogy and Petrology, 36(1): 13-25 |

| [16] | Engi M and Lindsley DH. 1980. Stability of titanian clinohumite: Experiments and thermodynamic analysis. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 72(4): 415-424 |

| [17] | Evans BW, Johannes W, Oterdoom WH and Trommsdorff V. 1976. Stability of chrysotile and antigorite in the serpentine multisystem. Schweiz. Mineral. Petrogr. Mitt., 56: 79-93 |

| [18] | Evans BW and Trommsdorff V. 1978. Petrogenesis of garnet lherzolite, Cima di Gagnone, Lepontine Alps. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 40(3): 333-348 |

| [19] | Evans BW. 2004. The serpentinite multisystem revisited: Chrysotile is metastable. International Geology Review, 46(6): 479-506 |

| [20] | Evans BW, Hattori K and Baronnet A. 2013. Serpentinite: What, why, where? Elements, 9(2): 99-106 |

| [21] | Ferraris G, Mellini M and Merlino S. 1986. Polysomatism and the classification of minerals. Rend. Soc. Ltal. Mineral. Petrol., 41: 181-192 |

| [22] | Franz G and Ackermand D. 1980. Phase relations and metamorphic history of a Clinohumite-chlorite-serpentine-marble from the Western Tauern Area (Austria). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 75(2): 97-110 |

| [23] | Fujino K and Takéuchi Y. 1978. Crystal chemistry of titanian chondrodite and titanian clinohumite of high-pressure origin. American Mineralogist, 63(5-6): 535-543 |

| [24] | Fyfe WS and McBirney AR. 1975. Subduction and the structure of andesitic volcanic belts. American Journal of Science, 275-A: 285-297 |

| [25] | Ghaderi N, Zhang H and Sun T. 2015. Relative stability and contrasting elastic properties of serpentine polymorphs from first-principles calculations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 120(7): 4831-4842 |

| [26] | Groppo C, Rinaudo C, Cairo S, Gastaldi D and Compagnoni R. 2006. Micro-Raman spectroscopy for a quick and reliable identification of serpentine minerals from ultramafics. European Journal of Mineralogy, 18(3): 319-329 |

| [27] | Harvey J, Garrido CJ, Savov I, Agostini S, Padrón-Navarta JA, Marchesi C, López Sánchez-Vizcaíno V and Gómez-Pugnaire MT. 2014. 11B-rich fluids in subduction zones: The role of antigorite dehydration in subducting slabs and boron isotope heterogeneity in the mantle. Chemical Geology, 376: 20-30 |

| [28] | Hattori KH and Guillot S. 2003. Volcanic fronts form as a consequence of serpentinite dehydration in the forearc mantle wedge. Geology, 31(6): 525-528 |

| [29] | Hattori KH and Guillot S. 2007. Geochemical character of serpentinites associated with high- to ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic rocks in the Alps, Cuba, and the Himalayas: Recycling of elements in subduction zones. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems, 8(9), doi: 10.1029/2007GC001594 |

| [30] | Hermann J, Fitz Gerald JD, Malaspina N, Berry AJ and Scambelluri M. 2007. OH-bearing planar defects in olivine produced by the breakdown of Ti-rich humite minerals from Dabie Shan (China). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 153(4): 417-428 |

| [31] | Hilairet N, Daniel I and Reynard B. 2006. Equation of state of antigorite, stability field of serpentines, and seismicity in subduction zones. Geophysical Research Letters, 33(2): L02302 |

| [32] | Hilairet N, Reynard B, Wang YB, Daniel I, Merkel S, Nishiyama N and Petitgirard S. 2007. High-pressure creep of serpentine, interseismic deformation, and initiation of subduction. Science, 318(5858): 1910-1913 |

| [33] | Hyndman RD and Peacock SM. 2003. Serpentinization of the forearc mantle. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 212(3-4): 417-432 |

| [34] | Isabel RDC, Barriga FJAS, Viti C, Mellini M and Wicks FJ. 2008. Antigorite in deformed serpentinites from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. European Journal of Mineralogy, 20(4): 563-572 |

| [35] | Johannes W. 1968. Experimental investigation of the reaction forsterite + H2O serpentine + brucite. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 19(4): 309-315 |

| [36] | Kawakatsu H and Watada S. 2007. Seismic evidence for deep-water transportation in the mantle. Science, 316(5830): 1468-1471 |

| [37] | Kearns LE, Kite LE, Leavens PB and Nelen JA. 1980. Fluorine distribution in the hydrous silicate minerals of the Franklin Marble, Orange County, New York. American Mineralogist, 65(5-6): 557-562 |

| [38] | Kocman V and Rucklidge J. 1973. The crystal structure of a titaniferous clinohumite. American Mineralogist, 58: 1097-1098 |

| [39] | Kunze G. 1961. Antigorit. Strukturtheoretische Grundlagen und ihre praktische Bedeutung für die weitere Serpentin-Forschung. Fortschr. Mineral., 39: 206-324 |

| [40] | Li XP, Rahn M, Bucher K and Zhang LF. 2003. Lithological association of ultramafic rocks in ophiolites: Serpentinite, rodingite and ophicarbonate: An example from Zermatt-Sass of western Alps. Earth Science Frontiers, 10(4): 457-468 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [41] | Liou JG, Zhang RY, Ernst WG, Rumble D and Maruyama S. 1998. High-pressure minerals from deeply subducted metamorphic rocks. In: Hemley RJ (ed.). Ultrahigh-Pressure Mineralogy: Physics and Chemistry of the Earth's Deep Interior (Reviews in Mineralogy). Washington DC: Mineralogical Society of America, 37: 33-96 |

| [42] | López Sánchez-Vizcaíno V, Trommsdorff V, Gómez-Pugnaire MT, Garrido CJ, Müntener O and Connolly JAD. 2005. Petrology of titanian clinohumite and olivine at the high-pressure breakdown of antigorite serpentinite to chlorite harzburgite (Almirez Massif, S. Spain). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 149(6): 627-646 |

| [43] | López Sánchez-Vizcaíno V, Gómez-Pugnaire MT, Garrido CJ, Padrón-Navarta JA and Mellini M. 2009. Breakdown mechanisms of titanclinohumite in antigorite serpentinite (Cerro del Almirez massif, S. Spain): A petrological and TEM study. Lithos, 107(3-4): 216-226 |

| [44] | Mazzoli S, Martín-Algarra A, Reddy SM, López Sánchez-Vizcaíno V, Fedele L and Noviello A. 2013. The evolution of the footwall to the Ronda subcontinental mantle peridotites: Insights from the Nieves Unit (western Betic Cordillera). Journal of the Geological Society, 170(3): 385-342 |

| [45] | McGetchin TR, Silver LT and Chodos AA. 1970. Titanoclinohumite: A possible mineralogical site for water in the upper mantle. Journal of Geophysical Research, 75(2): 255-259 |

| [46] | Mellini M and Zussman J. 1986. Carlosturanite (not "picrolite") from Taberg, Sweden. Mineralogy Magazine, 50(358): 675-679 |

| [47] | Mellini M, Trommsdorff V and Compagnoni R. 1987. Antigorite polysomatism: Behaviour during progressive metamorphism. Contribution to Mineralogy and Petrology, 97(2): 147-155 |

| [48] | Mével C. 2003. Serpentinization of abyssal peridotites at mid-ocean ridges. Comptes Rendus Géoscience, 335(10): 825-852 |

| [49] | Mysen BO, Ulmer P, Konzett J and Schmidt MW. 1998. The upper mantle near convergent plate boundaries. In: Hemley RJ (ed.). Ultrahigh-Pressure Mineralogy: Physics and Chemistry of the Earth's Deep Interior. Washington, DC: Mineralogical Society of America, 37: 97-138 |

| [50] | Nestola F, Angel RJ, Zhao J, Garrido CJ, Sánchez-Vizcaíno VL, Capitani G and Mellini M. 2010. Antigorite equation of state and anomalous softening at 6GPa: An in situ single-crystal X-ray diffraction study. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 160(1): 33-43 |

| [51] | O'Hanley DS, Chernosky JV and Wicks FJ. 1989. The stability of lizardite and chrysotile. The Canadian Mineralogist, 27(3): 483-493 |

| [52] | O'Hanley DS and Wicks FJ. 1995. Conditions of formation of lizardite, chrysotile and antigorite, Cassiar, British Columbia. The Canadian Mineralogist, 33(4): 753-773 |

| [53] | Okay AI. 1994. Sapphirine and Ti-clinohumite in ultra-high-pressure garnet-pyroxenite and eclogite from Dabie Shan, China. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 116(1): 145-155 |

| [54] | Padrón-Navarta JA, López Sánchez-Vizcaíno V, Garrido CJ and Gómez-Pugnaire MT. 2011. Metamorphic record of high-pressure dehydration of antigorite serpentinite to chlorite harzburgite in a subduction setting (Cerro del Almirez, Nevado-Filábride Complex, Southern Spain). Journal of Petrology, 52(10): 2047-2078 |

| [55] | Padrón-Navarta JA, Sánchez-Vizcaíno VL, Hermann J, Connolly JAD, Garrido CJ, Gómez-Pugnaire MT and Marchesi C. 2013. Tschermak's substitution in antigorite and consequences for phase relations and water liberation in high-grade serpentinites. Lithos, 178: 186-196 |

| [56] | Peacock SA. 1990. Fluid processes in subduction zones. Science, 248(4953): 329-337 |

| [57] | Pearson DG, Brenker FE, Nestola F, McNeill J, Nasdala L, Hutchison MT, Matveev S, Mather K, Silversmit G, Schmitz S, Vekemans B and Vincze L. 2014. Hydrous mantle transition zone indicated by ringwoodite included within diamond. Nature, 507(7491): 221-224 |

| [58] | Perrillat JP, Daniel I, Koga KT, Reynard B, Cardon H and Crichton WA. 2005. Kinetics of antigorite dehydration: A real-time X-ray diffraction study. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 236(3-4): 899-913 |

| [59] | Rahn MK and Rahn K. 1998. Titanian clinohumite formation in the Zermatt-Saas ophiolites, Central Alps. Mineralogy and Petrology, 64(1-4): 1-13 |

| [60] | Ranero CR, Phipps Morgan J, McIntosh K and Reichert C. 2003. Bending-related faulting and mantle serpentinization at the Middle America trench. Nature, 425(6956): 367-373 |

| [61] | Rice JM. 1977. Contact metamorphism of impure dolomitic limestone in the Boulder Aureole, Montana. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 59(3): 237-259 |

| [62] | Rinaudo C, Gastaldi D and Belluso E. 2003. Characterization of chrysotile, antigorite and lizardite by FT-Raman spectroscopy. The Canadian Mineralogist, 41(4): 883-890 |

| [63] | Robinson K, Gibbs GV and Ribbe PH. 1973. The crystal structure of the humite minerals. IV. Clinohumite and titanoclinohumite. American Mineralogist, 58: 43-49 |

| [64] | Scambelluri M, Hoogerduijn Strating EH, Piccardo GB, Vissers RLM and Rampone E. 1991. Alpine olivine- and titanian clinohumite-bearing assemblages in the Erro-Tobbio peridotite (Voltri Massif, NW Italy). Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 9(1): 79-91 |

| [65] | Scambelluri M, Müntener O, Hermann J, Piccardo GB and Trommmsdorff V. 1995. Subduction of water into the mantle: History of an Alpine peridotite. Geology, 23(5): 459-462 |

| [66] | Scambelluri M and Rampone E. 1999. Mg-metasomatism of oceanic gabbros and its control on Ti-clinohumite formation during eclogitization. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 135(1): 1-17 |

| [67] | Scambelluri M, Pettke T, Rampone E, Godard M and Reusser E. 2014. Petrology and trace element budgets of high-pressure peridotites indicate subduction dehydration of serpentinized mantle (Cima di Gagnone, Central Alps, Switzerland). Journal of Petrology, 55(3): 459-498 |

| [68] | Scambelluri M, Pettke T and Cannaò E. 2015. Fluid-related inclusions in Alpine high-pressure peridotite reveal trace element recycling during subduction-zone dehydration of serpentinized mantle (Cima di Gagnone, Swiss Alps). Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 429: 45-59 |

| [69] | Schwartz S, Guillot S, Reynard B, Lafay R, Debret B, Nicollet C, Lanari P and Auzende AL. 2013. Pressure-temperature estimates of the lizardite/antigorite transition in high pressure serpentinites. Lithos, 178: 197-210 |

| [70] | Shen TT, Hermann J, Zhang LF, Padrón-Navarta JA and Chen J. 2014. FTIR spectroscopy of Ti-chondrodite, Ti-clinohumite, and olivine in deeply subducted serpentinites and implications for the deep water cycle. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 167(4): 992, doi: 10.1007/s00410-014-0092-8 |

| [71] | Shen TT, Hermann J, Zhang LF, Lü Z, Padrón-Navarta JA, Xia B and Bader T. 2015. UHP metamorphism documented in Ti-chondrodite- and Ti-clinohumite-bearing serpentinized ultramafic rocks from Chinese southwestern Tianshan. Journal of Petrology, 56(7): 1425-1458 |

| [72] | Smith D. 1977. Titanochondrodite and Titanoclinohumite derived from the upper mantle in the Buell Park kimberlite, Arizona, USA. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 61(2): 213-215 |

| [73] | Strunz H. 1970. Mineralogische Tabellen, 5. Auflage. Leipzig, Germany: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Geest and Portig KG |

| [74] | Syracuse EM, van Keken PE and Abers GA. 2010. The global range of subduction zone thermal models. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, 183(1-2): 73-90 |

| [75] | Thompson JB. 1978. Biopyriboles and polysomatic series. American Mineralogist, 63(3-4): 239-249 |

| [76] | Trommsdorff V and Evans BW. 1980. Titanian hydroxyl-clinohumite: Formation and breakdown in antigorite rocks (Malenco, Italy). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 72(3): 229-242 |

| [77] | Trommsdorff V. 1983. Metamorphose magnesiumreicher Gesteine: Kritischer Vergleich von Natur, experiment und thermodynamischer datenbasis. Fortschr. Mineral., 61: 283-308 |

| [78] | Trommsdorff V, Sánchez-Vizcaíno VL, Gómez-Pugnaire MT and Müntener O. 1998. High pressure breakdown of antigorite to spinifex-textured olivine and orthopyroxene, SE Spain. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 132(2): 139-148 |

| [79] | Trommsdorff V, Risold AC, Reusser E, Connolly J and Ulmer P. 2001. Titanian clinohumite: Ilmenite rod inclusions and phase relations, Central Alps. In: Abstr Vol UHPM Worksh 2001 Fluid/Slab/Mantle Interactions and Ultrahigh-P-Minerals. Tokyo: Waseda University |

| [80] | Ulmer P and Trommsdorff V. 1995. Serpentine stability to mantle depths and subduction-related magmatism. Science, 268(5212): 858-861 |

| [81] | Wei CJ and Powell R. 2003. Phase relations in high-pressure metapelites in the system KFMASH (K2O-FeO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O) with application to natural rocks. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 145(3): 301-315 |

| [82] | Wei CJ and Powell R. 2005. Calculated phase relations in the system NCKFMASH (Na2O-CaO-K2O-FeO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O) for high-pressure metapelites. Journal of Petrology, 47(2): 385-408 |

| [83] | Wei CJ and Zhang YH. 2008. Phase transition in the subducted oceanic lithosphere and generation of the subduction zone magma. Chinese Science Bulletin, 53(23): 3603-3614 |

| [84] | Wei CJ and Clarke GL. 2011. Calculated phase equilibria for MORB compositions: A reappraisal of the metamorphic evolution of lawsonite eclogite. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 29(9): 939-952 |

| [85] | Weiss M. 1997. Clinohumites: A field and experimental study. Ph. D. Dissertation. Zurich: Swiss federal Institte of Technology (ETH), 1-154 |

| [86] | Whitney DL and Evans BW. 2010. Abbreviations for names of rock-forming minerals. American Mineralogist, 95(1): 185-187 |

| [87] | Wunder B and Schreyer W. 1997. Antigorite: High-pressure stability in the system MgO-SiO2-H2O (MSH). Lithos, 41(1-3): 213-227 |

| [88] | Wunder B. 1998. Equilibrium experiments in the system MgO-SiO2-H2O (MSH): Stability fields of clinohumite-OH [Mg9Si4O16(OH)2], chondrodite-OH [Mg5Si2O8(OH)2] and phase A [Mg7Si2O8(OH)6]. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 132(2): 111-120 |

| [89] | Wunder B, Wirth R and Gottschalk M. 2001. Antigorite: Pressure and temperature dependence of polysomatism and water content. European Journal of Mineralogy, 13(3): 485-495 |

| [90] | Xu ZQ, Chen J, Yang JS, Li XP and Chen FY. 2003. Discovery of Titanoclinohumite and Titanochondrodite exsolution in clinopyroxene included in Garnet peridotite and their significance. Acta Geologica Sinica, 77(4): 549-555 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [91] | Yamamoto K and Akimoto S. 1977. The system MgO-SiO2-H2O at high pressures and temperatures; stability field for hydroxyl-chondrodite, hydroxyl-clinohumite and 10Å pahase. American Journal of Science, 277(3): 288-312 |

| [92] | Yang JJ. 2003. Titanian clinohumite-garnet-pyroxene rock from the Su-Lu UHP metamorphic terrane, China: Chemical evolution and tectonic implications. Lithos, 70(3-4): 359-379 |

| [93] | Zussman J, Brindley GW and Comer JJ. 1957. Electron diffraction studies of serpentine minerals. American Mineralogist, 42: 133-153 |

| [94] | 李旭平, Rahn M, Bucher K, 张立飞. 2003. 蛇绿岩套中超基性岩体的岩石组合: 蛇纹岩、异剥钙榴岩和蛇绿碳酸岩-以西阿尔卑斯Zermatt-Saas蛇绿岩为例. 地学前缘, 10(4): 457-468 |

| [95] | 魏春景, 张颖慧. 2008. 俯冲大洋岩石圈的相转变与俯冲带岩浆作用. 科学通报, 53(20): 2449-2459 |

| [96] | 许志琴, 陈晶, 杨经绥, 李旭平, 陈方远.2003. 苏鲁超高压变质带石榴石橄榄岩中含钛硅镁石出溶体的发现及其意义. 地质学报,77(4): 549-555 |

2016, Vol. 32

2016, Vol. 32