2. 中国科学院大学,北京 100049

3. 中国科学院广州地球化学研究所 矿物学和成矿学重点实验室,广州 510640

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

3. Key Laboratory of Mineralogy and Metallogeny, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China

蛇纹石化是指基性岩(例如玄武岩)和超基性岩(橄榄岩、科马提岩等)的一种水热蚀变,主要产物为蛇纹石、(±)水镁石、(±)滑石、(±)磁铁矿和氢气。基性或超基性岩发生蛇纹石化后形成蛇纹岩,矿物组成主要是蛇纹石。蛇纹石化过程中,橄榄石和辉石中释放出的Fe2+被氧化成Fe3+,同时水中的氢被还原成氢气。当体系中有二氧化碳时,二氧化碳可被还原为甲烷、乙烷、丙烷等 (Berndt et al., 1996)。因此,以橄榄岩或玄武岩为基底岩石的海底热液常有高含量的氢气和甲烷(Charlou et al., 1998; Kelley et al., 2001)。海底热液往往支撑独特的生物活动系统,温度为20~>350℃,溶液的pH为3~11,常有各种微生物,有些环境下还有虾和螃蟹(Kelley et al., 2001)。蛇纹石化过程中产生的氢气和甲烷为海洋微生物提供能量,这可能代表着地球和其他行星的早期生命演化 (Schrenk et al., 2013)。

蛇纹石化可以出现在不同的构造环境中,例如深海、扩张洋脊和俯冲带等(Mével, 2003)。深海橄榄岩基本上已经全部发生了蛇纹石化(Allen and Seyfried, 2003)。已经发现的Lost City、Rainbow等热液区的基底岩石均为蛇纹石化的橄榄岩。深海橄榄岩可以在低温 (<100℃,例如Lost City热液区)或者高温(>300℃,例如Rainbow热液区)条件下蚀变。在慢速或超慢速扩张洋脊中,也常发生蛇纹石化(Charlou et al., 1998; Beard et al., 2009)。此外,蛇纹石化也会出现在活动板块边缘,例如在Tonga海沟和Mariana海沟中也发现了蛇纹石化的橄榄岩 (Fisher and Engel, 1969; Bloomer, 1983)。俯冲过程中,地幔楔橄榄岩受到板块脱水流体的交代形成蛇纹岩 (Maekawa et al., 2001; Hyndman and Peacock, 2003)。Izu-Bonin和Mariana的弧前存在由大量的蛇纹石化橄榄岩组成的海底山脉 (Fryer et al., 1985)。

蛇纹石是含水矿物,其水含量高达13%,可在温度<650℃,压力小于5GPa时保持稳定 (Ulmer and Trommsdorff, 1995)。随着板块俯冲的进行,蛇纹石被带到深部。高温时蛇纹石容易分解,产生水、橄榄石等。蛇纹石分解产生的水可能对岛弧岩浆的形成有重要作用(Hattori and Guillot, 2003)。此外,蛇纹石富Cl,可高达0.6% (Bonifacie et al., 2008; Anselmi et al., 2000; Kodolányi et al., 2012)。除Cl外,蛇纹石也富集B、F、Li、As、Pb、Sb和Sr等元素(Mével, 2003)。研究表明,俯冲过程中,B、Li、As和Pb等元素在低温时富集在蛇纹岩中,而在高温时 (>700℃) 随着蛇纹石脱水进入到流体中,进而随着流体交代地幔楔,使得岛弧岩浆富集As和Pb等元素 (Hattori and Guillot, 2003)。值得一提的是,铁矿、银矿等矿床可赋存于蛇纹岩中,这表明蛇纹石化可能造成成矿元素的迁移和富集。

综上可知,研究蛇纹石化有助于理解海底热液的成分演化,以及蛇纹石化过程中元素的迁移。本文主要从以下4个方面探讨蛇纹石化的机理以及其成矿潜力:(1)蛇纹石化的产物,主要介绍蛇纹石化过程中流体的组成,蛇纹石化过程中产生氢气的量,利蛇纹石、纤蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石的形成条件,水镁石的形成条件,以及磁铁矿的形成;(2)蛇纹石化的反应速率;(3)蛇纹石化过程中元素的迁移;(4)蛇纹石化的成矿潜力。

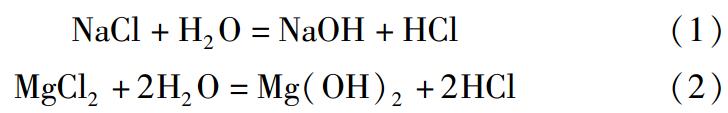

与基性或超基性岩相关的热液区,例如Rainbow、Lost City和Lucky Strike等,其流体成分可能受到蛇纹石化的影响。从表 1可以看出,高温时(>300℃)热液流体的pH小于5,而低温时(40~75℃)热液流体的pH为8.0。热力学计算表明,50℃时流体的pH约为11,400℃时流体的pH约为6 (McCollom and Bach, 2009)。水热实验的结果也表明低温时流体的pH较高,例如200℃、500bar时,橄榄岩蚀变后流体的pH为12.2 (Seyfried et al., 2007)。流体的pH和溶液中Na、K、Fe、Mg、Al和Si的含量有关。NaCl(aq)可以水解成NaOH和HCl(反应方程式(1)),高温时(>300℃),NaOH的电离常数大于HCl的电离常数,NaCl(aq)呈碱性(王玉荣等,1981)。实验表明,300℃、500bar时,含Mg的溶液和玄武岩反应使得流体的pH由初始的7.72降低至6.62,而不含Mg的溶液和玄武岩的反应使得溶液的pH由初始的6.00升高至6.31(Seyfried and Bischoff, 1981)。MgCl2水解为Mg(OH)2和HCl(反应方程式(2)),Mg(OH)2的电离常数随着温度的升高而降低,这导致高温时流体的pH低(McCollom and Bach, 2009)。流体中Mg、Fe等含量是和未蚀变岩石的类型、初始流体和蚀变程度相关的。

|

|

表1 热液流体的组成 Table 1 Hydrothermal fluid composition |

由表 1还可以看出,Ca、Mg和Si在蛇纹石化过程中是活动的。Ca可富集在流体中,主要来自于单斜辉石的蚀变。400℃、500bar时,有单斜辉石的矿物组合(60%的斜方辉石和40%的单斜辉石,或者76%的橄榄石、17%的斜方辉石和7%的单斜辉石)蚀变所产生的流体中的Ca可达40mmol/kg (Allen and Seyfried, 2003),这比橄榄石和斜方辉石蚀变所产生的Ca要高得多。相同的温度压力条件下,橄榄石蚀变后流体中Ca的浓度低于0.3mmol/kg,斜方辉石蚀变后流体中Ca的浓度最高为7.2mmol/kg(Allen and Seyfried, 2003)。Mg在流体中的含量和含Mg矿物的结晶有关。实验表明,200℃、500bar时,随着蛇纹石化的进行,流体中的Mg由初始的59mmol/kg降至低于检出限,这是由于蛇纹石和水镁石的结晶会消耗流体中的Mg (Seyfried et al., 2007)。400℃、500bar时,橄榄石蚀变后流体中的Mg由初始的48~60mmol/kg降至27mmol/kg;斜方辉石蚀变后流体中的Mg降至5.1mmol/kg;两种矿物组合(同上)蚀变后流体中的Mg降至1mmol/kg (Allen and Seyfried, 2003)。流体中的Si主要来自斜方辉石和单斜辉石的溶解。400℃、500bar时,矿物组合蚀变后(60%斜方辉石和40%单斜辉石)流体中的SiO2浓度为4.2mmol/kg,而橄榄石蚀变后流体中的SiO2浓度仅为0.2mmol/kg (Allen and Seyfried, 2003)。

蛇纹石化过程中氢气的产生是由于橄榄石和辉石中的Fe2+被氧化成Fe3+,水中的氢被还原成氢气。300℃、300bar时,蛇纹石化产生氢气的量和蛇纹岩的Fe3+/ΣFe成线性正相关 (Marcaillou et al., 2011)。低温时(<300℃),氢气主要来自于橄榄石的蚀变(McCollom and Bach, 2009);当温度约为300℃时,橄榄石的蚀变最快,产生氢气的量最大(Malvoisin et al., 2012b); 而随着温度的增加,橄榄石的反应速率低于辉石,橄榄石蚀变产生的氢气低于辉石蚀变产生的氢气的量(Allen and Seyfried, 2003)(表 2)。热力学计算表明(水/岩比为1),50℃时橄榄岩蚀变仅产生7mmol/kg氢气; 315℃时

|

|

表2 蛇纹石化实验产生氢气和甲烷的量 Table 2 The amount of hydrogen gas and methane generated during serpentinization experiments |

生成约360mmol/kg氢气;400℃时产生氢气的量低于70mmol/kg,此时氢气主要来自于辉石的蚀变(McCollom and Bach, 2009)。总的来说,氢气的产生受蛇纹石化反应动力学的制约。实验表明,蛇纹石化产生氢气的量随着反应的进行逐渐增加,但氢气的产生速率则随着反应的进行逐渐降低(Allen and Seyfried, 2003)。在封闭体系中,随着氢气的量增加,氢气的分压增大,可能会使得反应速率减小。

研究表明,橄榄岩在蛇纹石化过程中产生的氢气大于玄武岩蚀变产生氢气的量(McCollom and Bach, 2009)。当玄武岩发生蛇纹石化时,部分Fe2+进入绿泥石和角闪石中,使得生成的Fe3+的量减少,最终导致产生氢气的量也减少 (McCollom and Bach, 2009)。表 1中Rainbow的基底岩石是橄榄岩,热液含16mmol/kg的H2和2.5mmol/kg的CH4;TAG热液区的基底岩石是玄武岩,热液中H2和CH4的含量远小于Rainbow热液区,分别为0.18~0.23mmol/kg和0.15~0.16mmol/kg。

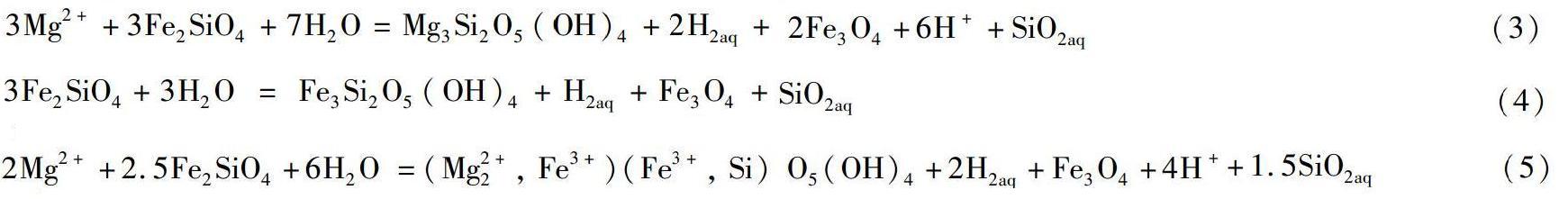

同样,蛇纹石的Fe2+和Fe3+含量也会影响生成氢气的量(Evans et al., 2009)。如果Fe全部富集在磁铁矿中而蛇纹石几乎不含Fe,则反应方程式可以用(3)表达,此时1mol的Fe2SiO4完全反应可以生成0.67mol的氢气。如果蛇纹石中的八面体位置全部为Fe2+,且没有Fe3+替代四面体的Si和八面体的Mg,则方程式可以用(4)表示,此时1mol的Fe2SiO4完全反应可以生成0.33mol的H2。可见,Fe2+富集在蛇纹石中会降低生成氢气的量。如果蛇纹石中只有Fe3+,Fe3+既替代四面体的Si又替代八面体的Mg,则反应方程式可以用(5)表示,此时1mol的Fe2SiO4完全反应生成1.25mol的氢气。可见,Fe3+富集在蛇纹石中使得生成氢气的量增加。这里需注意的是,蛇纹石中只有Fe3+属于极端情况,尚未见报道。Evans et al. (2009) 报道的蛇纹石中的Fe3+/ΣFe最大为0.70,Marcaillou et al. (2011) 报道的蛇纹石中的Fe3+/ΣFe为0.67,其中蛇纹石中的IVFe/ΣFe为0.12。

近年来的研究表明,催化剂的加入使得费托合成产生高含量的烷烃,例如,Fe-Ni合金、铬铁矿、含Co的磁铁矿等 (Horita and Berndt, 1999; Foustoukos and Seyfried, 2004;Ji et al., 2008)。Fe-Ni合金可以大幅度增加CH4的产量,但不能增加C2H6和C3H8的产量 (Horita and Berndt, 1999)。铬铁矿可以增加CH4、C2H6和C3H8的产量 (Foustoukos and Seyfried, 2004)。但含镁的铬铁矿不是催化剂。实验表明,天然科马提岩蚀变时加入19%含镁铬铁矿使得甲烷的产量增加,但是合成的科马提岩和加了19%含镁铬铁矿的合成科马提岩蚀变产生甲烷的量几乎相同,这说明含镁铬铁矿不是费托合成的催化剂(Lazar et al., 2012)(表 2)。含Co的磁铁矿不仅可以增加CH4、C2H6和C3H8的产量,还可以增加C4H10和C5H12的产量 (Ji et al., 2008)。

蛇纹石为层状矿物,由Si-O四面体和Mg-O八面体组成。Al和Fe3+可替代四面体位置的Si,Fe2+、Fe3+、Cr、Al、Ni和Mn可替代八面体位置的Mg。蛇纹石主要有利蛇纹石、纤蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石三种,化学式为Mg3Si2O5(OH)4。虽然三种蛇纹石的化学式相同,但其矿物结构有很大的不同。Si-O四面体和Mg-O八面体呈1:1排布,利蛇纹石呈平面状,纤蛇纹石为卷轴状,而叶蛇纹石由于四面体和八面体的周期性的错位,导致一些八面体位置的缺失,呈波浪状。此外,在化学成分上这三种蛇纹石也有一定差异。比如,利蛇纹石可以容纳更多的Al和Fe;叶蛇纹石相对其他两种蛇纹石更加富Si贫Mg (Uehara and Shirozu, 1985)。利蛇纹石含38%~40% SiO2 (O'Hanley and Dyar, 1993),叶蛇纹石SiO2含量为42%~45% (Dugan, 1979)。

蛇纹石的成分变化较大。由橄榄石蚀变形成的蛇纹石的成分相对贫Al和Cr,富Ni,而由辉石蚀变形成的蛇纹石相对富Al和Cr (Mével, 2003)。蛇纹石的Mg#变化较大,Mg#受到很多外界条件的影响。氧逸度会影响蛇纹石的Fe2+/Fe3+比值,从而会影响Mg#。此外,当蛇纹石不发生重结晶时,生成磁铁矿的多少会影响蛇纹石的Mg#:生成磁铁矿的量多时,蛇纹石相对贫Fe,Mg#较高;生成的磁铁矿少时,蛇纹石相对富Fe,Mg#较低。另外,三种蛇纹石的FeO/Fe2O3是不同的。O'Hanley and Dyar (1993) 通过对蛇纹石矿物的电子探针和穆斯堡尔谱的研究表明,利蛇纹石中Fe2+含量低 (FeO/Fe2O3=0.28±0.21,5个样品;Fe2+/Fe3+=0.7±0.54,10个样品),叶蛇纹石中Fe2+含量最高 (FeO/Fe2O3=2.9±1.7, 3个样品;Fe2+/Fe3+=3.25,1个样品),纤蛇纹石中Fe2+居于以上两种蛇纹石的中间 (FeO/Fe2O3=1.5 ±1.4,6个样品;Fe2+/Fe3+=0.41,2个样品)。

利蛇纹石、纤蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石的稳定温度和压力区间一直备受争议。热力学计算表明,利蛇纹石、纤蛇纹石和叶蛇纹石的形成温度分别为125℃、180℃和235℃ (O'Hanley, 1996)。然而,这并不意味着利蛇纹石只能在温度低于125℃时出现。海底的蛇纹岩主要是由利蛇纹石组成,18O表明温度大于300℃ (Mével, 2003)。此外,水热实验表明,300℃、500bar时海水和橄榄岩反应所产生的蛇纹石主要为利蛇纹石 (Seyfried and Dibble, 1980)。Al和Fe的加入使得利蛇纹石的稳定区间增大,因此,利蛇纹石可能在相对高的温度压力下出现(O'Hanley, 1996)。同样,叶蛇纹石也可能在235℃下出现。Gunnarsson et al. (2005) 报道了叶蛇纹石可在39~150℃形成。叶蛇纹石和纤蛇纹石的形成受多种条件制约,例如,温度、压力、初始物MgO/SiO2摩尔比值和H2O含量的影响(Iishi and Saito, 1973)。高压有利于叶蛇纹石的形成,而高温有利于叶蛇纹石的形成(Iishi and Saito, 1973)。Wunder et al. (2001)报道了350℃、1GPa时有叶蛇纹石的出现。但是,Moody (1976)报道了349℃、1.99kbar时橄榄石和水的反应产物之一为利蛇纹石。

叶蛇纹石是板块俯冲的深部“供水矿物”。叶蛇纹石在500℃、7.0GPa下仍可保持稳定;更高压力时,则形成另一种含水矿物(Phase A, 化学式为Mg7Si2O8(OH)6) (Ulmer and Trommsdorff, 1995)。俯冲深度超过250km时,Phase A仍可以稳定(Schmidt and Poli, 1998)。含水矿物脱水产生的流体交代地幔楔,对岛弧岩浆的形成起着重要作用。

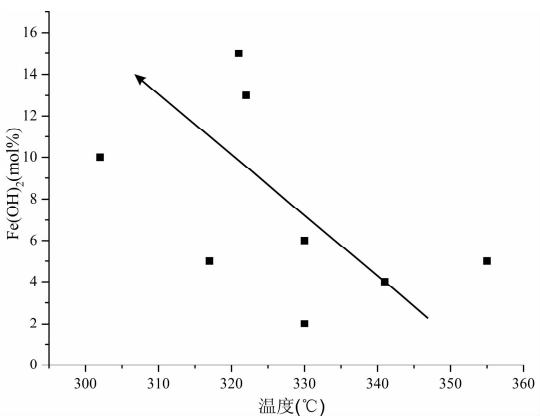

水镁石是蛇纹石化过程中的常见产物,化学式为(Mg, Fe)(OH)2。水镁石可以不同程度的富集Fe。热力学计算表明,低温时(<200℃),水镁石相对富集铁 (Mg#<70);随着温度的升高,水镁石中的Fe含量降低,Mg#升高 (McCollom and Bach, 2009)。富铁的水镁石多有报道,例如,大西洋洋中脊的蛇纹石化方辉橄榄岩和纯橄岩,其水镁石的Mg#=75,Fe含量较高 (Bach et al., 2006)。然而,橄榄石和水的蛇纹石化实验所产生的水镁石的Mg#较高,大于90 (Okamoto et al., 2011;Malvoisin et al., 2012a)。Moody (1976)的数据显示(图 1),水镁石中的Fe(OH)2 mol%随着温度的升高而降低,但误差较大(高达±9mol%)。

| 图1 不同温度下(实验温度为302~355℃,压力为1.01kbar)水镁石((Mg,Fe)(OH)2)的端元组分Fe(OH)2摩尔百分数(数据和误差来自于Moody, 1976) Fig.1 Mole percent of Fe(OH)2 in brucite ((Mg,Fe)(OH)2), at 302~355℃ and 1.01kbar (data and error were from Moody, 1976) |

虽然水镁石是蛇纹石化的常见产物,但并不是任何时候都会出现。300℃、300bar时,尖晶二辉橄榄岩和纯水的反应并不产生水镁石(Marcaillou et al., 2011)。纯橄岩和方辉橄榄岩的蛇纹石化常有水镁石的出现,而二辉橄榄岩的蛇纹石化通常不产生水镁石(O'Hanley, 1996)。下面讨论二辉橄榄岩之所以不产生水镁石的原因。首先,流体中SiO2浓度可能会影响水镁石的形成。当流体中的SiO2含量高时,水镁石会和SiO2反应生成蛇纹石,故水镁石在富SiO2的溶液中不稳定。当温度为300℃、压力为500bar、水/岩比为10时,二辉橄榄岩蚀变产生的流体含3.98mmol/kg Si,但方辉橄榄岩蚀变产生的流体仅含0.055mmol/kg Si (Janecky and Seyfried, 1986)。其次,溶液的pH值可能会影响水镁石的稳定性。由表 1可知,当温度为300℃、压力为500bar、水/岩比为10时,二辉橄榄岩蚀变产生的流体的pH为4.4,而方辉橄榄岩蚀变后流体的pH为11.46 (Janecky and Seyfried, 1986)。如果溶液的pH是影响水镁石形成的因素,那么水镁石在pH为4.4的溶液中是不稳定的。然而,Wang et al. (1998)将流体的pH控制在5左右以合成水镁石。可见,水镁石在pH约为5时是稳定的。因此,溶液的pH也不是影响水镁石生成的关键因素。此外,水镁石能在pH=13.5的碱性溶液中稳定(Lafay et al., 2012)。

水镁石为片状,常和蛇纹石长在一起,难以辨认,也难以估算其含量。在400℃、1GPa时,镁橄榄石完全蚀变生成78vol%的叶蛇纹石和22vol%的水镁石,但只有少量的水镁石能被观测到(O'Hanley, 1996)。水镁石可以用激光拉曼仪检测,主要的峰位是279cm-1、444cm-1和3650cm-1,少量的样品可用微束X射线衍射仪检测。

对蛇纹岩主量元素含量是否有变化的报道差别较大。有些研究者认为,和橄榄岩相比,蛇纹岩的主量元素(CaO, Al2O3, FeOT和MgO等)含量变化很小(Mével, 2003)。蛇纹石化过程中,橄榄岩中少量的CaO可进入流体中,流体中的H2O可进入蛇纹岩,而其他元素含量几乎无变化(Coleman and Keith, 1971)。但是,Costa et al. (2008)报道了蚀变后的橄榄岩的Fe2O3T变化很大(5.21%~19.77%),表明铁在蛇纹石化过程中是活动的。蛇纹石化过程中的Fe来自橄榄岩,蚀变后,Fe可以富集在流体、蛇纹石、水镁石和磁铁矿中。磁铁矿是蛇纹石化的常见产物,但并不是任何时候都会出现。蚀变产生的Fe3+可富集在蛇纹石中,而不是形成磁铁矿。目前已有研究报道蛇纹岩中并没有磁铁矿的出现(Evans et al., 2009; 汪小妹等, 2009)。以下从4个方面介绍磁铁矿的生成条件。

(1)磁铁矿的产生和蛇纹石化程度有关(Bach et al., 2006;Beard et al., 2009)。Bach et al., 2006通过观察洋中脊处蛇纹石化的方辉橄榄岩和纯橄岩表明,蚀变早期没有磁铁矿的出现,而晚期的蛇纹石脉中有磁铁矿。Beardet al. (2009)报道了蚀变样品中有两种脉,第一种脉的蚀变程度较低,叶蛇纹石和水镁石中的铁含量较高(高达10.88% FeO),无磁铁矿;第二种脉穿切第一种脉,蚀变程度较高,利蛇纹石仅含3.12%的FeO,有磁铁矿。Bach et al. (2006)认为蛇纹石化首先形成富铁的蛇纹石和水镁石,后期形成磁铁矿。这似乎表明产生的磁铁矿随着蛇纹石化程度的增加而增加。但是,当蛇纹石发生重结晶时,磁铁矿随着蛇纹石重结晶程度的增加而减少(O'Hanley and Dyar, 1993)。难以理解的是,橄榄石和水的反应中,磁铁矿在几小时内便可生成(Okamoto et al., 2011; Malvoisin et al., 2012b)。这表明橄榄石和橄榄岩反应是不同的。Malvoisin et al., 2012a认为生成的磁铁矿越多,蛇纹石化程度越高(见表 3)。

|

|

表3 不同温度下生成磁铁矿的量 Table 3 The amount of magnetite formed at different temperatures |

(2)蛇纹石的重结晶和不同种类蛇纹石之间的置换会影响生成的磁铁矿的量 (O'Hanley, 1996)。利蛇纹石发生重结晶时,形成新的利蛇纹石,或者置换为纤蛇纹石或叶蛇纹石。O'Hanley, 1996报道了不同的蛇纹岩中蛇纹石重结晶对生成磁铁矿的影响。对于Woodreef蛇纹岩而言,随着蛇纹石化程度的增强和利蛇纹石的重结晶,磁铁矿的量增加,而水镁石的量降低,利蛇纹石中的铁降低;而Jeffery蛇纹岩的磁铁矿降低,利蛇纹石中的铁增加 (O'Hanley, 1996)。可见,磁铁矿和蛇纹石化的程度关系较为复杂。

(3)温度会影响产生磁铁矿的量。表 3列出不同实验条件下生成的磁铁矿的量。水热实验表明,低温时(<200℃)无磁铁矿的产生 (Seyfried et al., 2007; Lafay et al., 2012)。同样,热力学计算也表明,Fe2+在低温时(<200℃)时很容易进入水镁石中,例如,50℃时,Mg#<70,这将导致产生磁铁矿的量降低(Foustoukos et al., 2008; McCollom and Bach, 2009)。高温时(>300℃),有磁铁矿的形成 (Moody, 1976; Janecky and Seyfried, 1986)。当温度为302~377℃, 压力为0.51~1.99kbar时,磁铁矿的量随着温度升高而增加(Moody, 1976)。但是,Evans (2010)认为,400~600℃时蛇纹石化的产物为富Mg的叶蛇纹石和富铁的橄榄石,无磁铁矿形成。相反,McCollom and Bach (2009)认为温度为400℃时,辉石的蚀变可产生磁铁矿。高温下是否有磁铁矿的产生需要相关的实验去验证。另外,由表 3还可以看出,方辉橄榄岩蚀变后生成的磁铁矿的量大于二辉橄榄岩蚀变后磁铁矿的量(Janecky and Seyfried, 1986)。这可能是由于方辉橄榄岩蚀变后的流体为碱性,流体中的Fe含量较低,铁易富集在磁铁矿中;二辉橄榄岩蚀变后产生酸性流体,流体中的Fe含量高,形成磁铁矿的量少。二辉橄榄岩蚀变后流体含1.59mmol/kg Fe,假定流体中的Fe全部生成磁铁矿,相当于0.12%的磁铁矿,这并不能解释方辉橄榄岩蚀变后高含量的磁铁矿(1.79%)。

(4) SiO2的活度(aSiO2)可能会影响磁铁矿的生成。当体系中的aSiO2较高时,较少的Fe3+会替代蛇纹石中的Si,导致磁铁矿的量增加(O'Hanley and Dyar, 1993)。方辉橄榄岩蚀变产生的磁铁矿为0.35%~0.57%,平均为0.44%,而纯橄岩蚀变产生的磁铁矿为0.15%~0.37%,平均为0.22% (Coleman and Keith, 1971)。这可能是由于方辉橄榄岩蚀变时流体中aSiO2较高所致。同样,Bach et al.(2006)认为磁铁矿易在高aSiO2的体系中形成。但是,Frost and Beard (2007)通过热力学计算表明,磁铁矿形成时体系中的aSiO2较低。相关的实验工作值得进一步开展。

磁铁矿可通过光学显微镜、电子显微镜、X射线衍射和磁力仪等方式检测。蛇纹石化过程中产生的磁铁矿比较小,约1μm (Janecky and Seyfried, 1986),或者<1~20μm (Malvoisin et al., 2012a),这种大小的磁铁矿可以用电子显微镜看到。由于磁铁矿和赤铁矿的背散射图像亮度很相似,电子显微镜很难将二者区分开。磁铁矿可以用拉曼光谱和透射电镜的电子衍射来鉴定。X射线衍射仪也可以鉴定磁铁矿,但只对高含量的磁铁矿适合(>2%)。磁力仪对磁铁矿很敏感,但天然的橄榄石常有细小的磁铁矿包裹体,这会干扰判定蛇纹石化过程中产生的磁铁矿的量(Belley et al., 2009)。

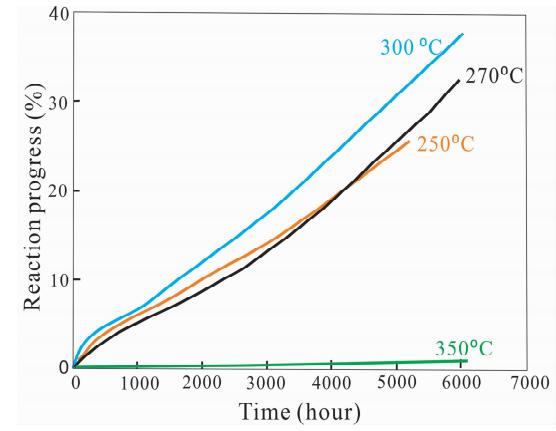

图 2总结了不同温度下橄榄石的蚀变程度(Malvoisin et al., 2012b)。橄榄石的蚀变在300℃时最强,350℃时橄榄石在6000小时内仅有约1.5%的蚀变,这和Martin and Fyfe (1970)的结果相似。辉石和橄榄石不同,在为80~560℃的温度区间内,随着温度的升高蚀变程度增强 (Martin and Fyfe, 1970)。

| 图2 不同温度下橄榄石的蚀变速率(据Malvoisin et al., 2012b) 实验压力均为500bar,初始物为橄榄石,颗粒大小为38~55μm Fig.2 Serpentinization progress at different temperatures (after Malvoisin et al., 2012b) Experiments were conducted at 500bar taking olivine as starting material with 38~55μm grain size |

图 3总结了不同实验研究中蛇纹石化的反应速率。天然橄榄石的蚀变速率比合成的橄榄石要慢很多。Martin and Fyfe (1970)采用合成镁橄榄石为初始物,和Malvoisin et al. (2012b)相比,前者的蚀变速率快。300℃时,合成的镁橄榄石(58~79μm) 在192小时内有60%的蚀变(Martin and Fyfe, 1970),而San Carlos橄榄石(50~63μm)在10000小时内的蚀变不超过50%。Martin and Fyfe (1970)认为蛇纹石化过程可能受扩散控制。然而,较多的实验观察到橄榄石等矿物表面出现溶蚀 (Lafay et al., 2012; Malvoisin et al., 2012b)。Lafay et al., 2012总结出蛇纹石化的三个步骤: (1)橄榄石的快速溶蚀,橄榄石表面上有诸如溶蚀坑等溶蚀特征,水镁石和纤蛇纹石沉淀在橄榄石的表面上。纤蛇纹石和水镁石小于100nm,并像节瘤一样附着在橄榄石表面上的;(2)纤蛇纹石和水镁石的生长;(3)橄榄石颗粒被裂隙分割,形成网状结构,使得蛇纹石化过程进一步进行。可见,蛇纹石化的过程是受橄榄石的溶蚀以及蛇纹石和水镁石的矿物生长等控制的,至少在300℃及300℃以下的温度时是如此。400~600℃时,Evans et al. (2010)认为蛇纹石化是受扩散控制的,橄榄石蚀变后生成富Mg的蛇纹石,残留的橄榄石富Fe,没有磁铁矿生成。

| 图3 蛇纹石化的反应速率 浅蓝色区域为Martin and Fyfe (1970)的数据,用合成的镁橄榄石和镁辉石作为实验的初始物,水是反应介质,实验温度210~245℃, 压力689.5~2758bar,矿物颗粒大小58~79μm;橘黄色表示的是Lafay et al. (2012)的数据,实验的初始矿物为San Carlos橄榄石,矿物颗粒大小分别为<30μm, 30~56μm和56~150μm,实验溶液是1mol/L NaOH溶液,水/岩比为15,实验温度200℃,压力160bar;深蓝色表示的是Malvoisin et al. (2012b)的数据,实验温度为250~350℃,压力为500bar。实验初始物为San Carlos橄榄石(Fo91)和水或0.56mol/L NaCl,水/岩比约为2.5。绿色的线表示Marcaillou et al. (2011)的实验数据,实验温度为300℃,压力是300bar,初始物是橄榄岩粉末,约1μm,水/岩比是1.67;红色的线表示Seyfried et al. (2007)的实验数据,温度为200℃,500bar,初始物是尖晶二辉橄榄岩粉末,50~100μm,水/岩比约为1 Fig.3 Kinetic studies on serpentinization The light blue line represents data of Martin and Fyfe (1970). The starting materials were synthetic forsterite and enstatite with grain sizes of 58~79μm, which interacted with distilled water at temperatures at ranges of 80~560℃, pressures at 689~2758bar; The orange lines represent the data shown in Lafay et al. (2012). The experiments were conducted at 200℃ and 160bar with San Carlos olivine as the starting materials. The solution used in Lafay et al. (2012) was 1mol/L NaOH and water/rock ratio was 15; The dark blue lines come from Malvoisin et al. (2012b). Experiments of Malvoisin et al. (2012b) were conducted at temperatures at ranges of 250~350℃, and pressure at 500bar. The starting materials were San Carlos olivine (Fo91) and pure water, with water/rock mass ratios around 2.5. A few experiments used 0.56mol/L NaCl instead of distilled water. The green line represents the experimental work of Marcaillou et al. (2011), which conducted experiments at 300℃ and 300bar with ground peridotite as starting material (1μm) and water/rock ratio around 1.67. Data of red line comes from Seyfried et al. (2007). Experiments were conducted at 200℃ and 500bar with ground peridotite as starting material (50~100μm) and water/rock ratio around 1 |

比较橄榄石和橄榄岩的蚀变速率(图 3)发现:当颗粒大小约1~5μm时,两者的蚀变速率很相似;当颗粒大于5μm时,橄榄岩的蚀变速率大于橄榄石(Seyfried et al., 2007; Marcaillou et al., 2011; Malvoisin et al., 2012b)。Malvoisin et al., 2012b以橄榄石为初始物 (38~50μm),250℃、500bar时,反应时间约215天时的蚀变程度为26%,而Seyfried et al. (2007)采用橄榄岩粉末为初始物 (50~100μm),200℃、500bar时,215天的反应时间对应的蚀变程度大于40%。和前者相比,后者的颗粒大、温度低,这些因素使得反应速率变慢,但即使如此,橄榄岩的反应速率仍大于橄榄石。

测定蛇纹石化蚀变程度的方法有两种:一是反应产物质量的增加。由于蛇纹石含有水,反应前后固体质量的增加可以表示参加反应的水的质量,以及反应程度。但是,这种方法的误差较大。另一种方法是反应过程中磁铁矿的增加 (Malvoisin et al., 2012b)。这种方法是基于蚀变程度是和生成的磁铁矿的量成正比这一先决条件的。这或许对于橄榄石的蚀变成立,但橄榄岩蚀变的早期可能不产生磁铁矿,因此用生成的磁铁矿的量来表示蚀变程度有待商榷。

Ca、Mg、Si和Fe在蛇纹石化过程中是活动的,这些元素可以赋存在流体中(参考表 1)。Al、Cr、Ni等元素在流体中的含量极低,但在蛇纹石化过程中也是活动的。橄榄石不含Al,但在蛇纹石化的橄榄岩中,由橄榄石蚀变生成的蛇纹石含0.3%~2.5% Al2O3,由斜方辉石蚀变的蛇纹石含1.5%~4.7% Al2O3 (Dugan, 1979)。橄榄石蚀变产生的蛇纹石中的Al来自于辉石或尖晶石。在辉石和尖晶石蚀变时,Al首先进入流体相,而后在蛇纹石结晶时进入其晶体结构。如果是这样,由橄榄石蚀变生成的蛇纹石和由辉石蚀变生成的蛇纹石中的Al2O3的量是相似的。但是,从整体上看,由辉石蚀变生成的蛇纹石的Al2O3的量比由橄榄石蚀变生成的蛇纹石的Al2O3的量要高。

Cr的活动性体现在铬铁矿或尖晶石的蚀变。典型的铬铁矿蚀变后形成三层蚀变环带:富Fe的铬铁矿环带、磁铁矿环带和硅酸岩环带 (Ulmer, 1974)。和未蚀变的铬铁矿相比,富Fe的铬铁矿环带中Al和Cr含量降低,而Fe含量增加。无蚀变的铬铁矿含53.0% Cr2O3、8.8% Al2O3和21.6% FeO;富Fe的铬铁矿环带含有3.3% MgO、52.1% FeO、37.8% Cr2O3和0.3% Al2O3;磁铁矿含有88.0% FeO、1.1% MgO、3.6% Cr2O3和0.1% Al2O3 (Ulmer, 1974)。Saumur and Hattori (2013)也报道了类似的现象,蚀变环带含有1.58% MgO、23.71% Fe2O3、29.26% FeO、41.86% Cr2O3和1.21% Al2O3, 和未蚀变的尖晶石相比(6.19% MgO、8.33% Fe2O3、24.54% FeO、44.68% Cr2O3、15.22% Al2O3),Fe2O3和FeO的量增加,Al、Mg和Cr含量降低。值得注意的是,Fe2O3的量是根据电子探针的数据得到的,不确定性较大(Saumur and Hattori, 2013)。和铬铁矿相比,富Al尖晶石不易蚀变 (Burkhard, 1993)。研究表明,富Al尖晶石的蚀变带由磁铁矿、利蛇纹石和绿泥石组成,这表明蚀变带的形成可能是由于蛇纹石和尖晶石反应形成磁铁矿和绿泥石(Mellini et al., 2005)。蛇纹石含少量的Cr,例如,Golightly and Arancibia (1979)报道的辉石蚀变形成的蛇纹石含0.83% Cr2O3。

Ni在蛇纹石化过程中是活动的。在橄榄岩中,Ni主要来自于橄榄石。蛇纹石化产生的流体中的Ni一般较低,低于2μmol/kg,但Rainbow热液区流体含3μmol/kg Ni(见表 1)。Ni可富集在蛇纹石和磁铁矿中。由橄榄石蚀变形成的蛇纹石含0.28% NiO,由辉石蚀变产生的蛇纹石含0.05% NiO (Golightly and Arancibia (1979))。Tehuitzingo蛇纹岩中蛇纹石含0.03%~0.79% NiO; Tso Morari蛇纹岩中磁铁矿含0.85% NiO,蛇纹石含0.07%~0.34% NiO (Gonzálz-Mancera et al., 2009; Deschamps et al., 2010)。

蛇纹石富Cl,其含量随着蛇纹石化的程度不同而不同 (Beard et al., 2009)。蛇纹石中的Cl高达0.6%(Anselmi et al., 2000; Bonifacie et al., 2008)。意大利中部的Elba、Monti Livornesi 和Murlo的蛇纹岩中Cl的含量为185×10-6~950×10-6 (Anselmi et al., 2000)。Cl在蛇纹石中不是以独立相存在,而是替代蛇纹石中的OH。Cl在蛇纹石中的含量不均一,蚀变的核部比边部的Cl含量高 (Anselmi et al., 2000)。此外,蛇纹石的Cl和主量元素没有相关关系,这表明蛇纹石中的Cl和化学成分无关 (Kodolányi et al., 2012)。水镁石中一般贫Cl,但仍有研究表明富水镁石的脉含0.21%~0.47% Cl (Kodolányi et al., 2012)。目前还没有相关的实验工作去验证Cl在蛇纹石化过程中如何受到温度、压力以及流体成分的影响。

Sr在蛇纹石化过程中容易富集在蛇纹岩中(Scambelluri et al., 2001; Scambelluri et al., 2004;Kodolányi et al., 2012; Lafay et al., 2013)。Erro-Tobbio蛇纹岩中的Sr含量高达38.8×10-6,而围岩中的Sr含量则小于8×10-6 (Scambelluri et al., 2001)。橄榄石中的Sr含量低 (0.002×10-6~0.02×10-6),单斜辉石中的Sr含量比蛇纹石中的低,蛇纹岩中的Sr主要富集在蛇纹石中 (Kodolányi et al., 2012)。蛇纹石(±水镁石)中的Sr含量为0.13×10-6~23×10-6 (Kodolányi et al., 2012)。相关的实验也表明Sr在蛇纹石化过程中易富集,300℃时,蚀变后的橄榄岩的 Sr含量由初始值<8×10-6增加到20×10-6~60×10-6 (Menzies et al., 1993)。同时,蛇纹石化产生的流体也富Sr,蛇纹岩中的流体包裹体中的Sr含量高达44×10-6 (Scambelluri et al., 2004)。

蛇纹石富集As和Sb (Hattori and Guillot, 2003;Hattori et al., 2005;Gonzálz-Mancera et al., 2009; Deschamps et al., 2010; Lafay et al., 2013)。由橄榄石蚀变形成的蛇纹石含18.49×10-6~54.92×10-6 As和4.16×10-6~18.37×10-6 Sb;由辉石蚀变后形成的蛇纹石含4.34×10-6~11.89×10-6 As和0.17×10-6~0.90×10-6 Sb (Deschamps et al., 2010)。可见由橄榄石蚀变形成的蛇纹石更易富集As和Sb。蛇纹岩也含有较高含量的As和Sb。Gonzálz-Manceraet al. (2009)报道的蛇纹岩中的As含量为2.80×10-6~70.6×10-6,Sb的含量为<0.2×10-6~3.00×10-6。As和Sb易在流体中富集,污染的地下水中的As含量可高达100×10-6 (Nordstrom, 2002)。As主要以As3+和As5+的价态存在,300℃且高氧逸度条件下,碱性流体中的As主要以HAsO42-形式存在,而酸性流体中的As主要以H3AsO3°的形式存在 (Hattori et al., 2005)。蛇纹石中的As主要以As5+为主,高达83% (Hattori et al., 2005)。As5+易在有机物、粘土矿物和铁锰氧化物中富集,故蛇纹石中的As可能主要来自于沉积物和俯冲板块(Hattori et al., 2005)。As和Sb是低温下活动的元素。Lafay et al. (2013)报道了五个期次的蛇纹岩,As和Sb在前四期次的蛇纹岩中逐渐富集(<480℃),As的含量高达3.97×10-6,Sb的含量高达0.995×10-6,而在第五期次的蛇纹岩中亏损(>480℃),As的含量为0.44×10-6~0.90×10-6,Sb的含量为0.029×10-6~0.049×10-6。可以看出As和Sb的富集和温度有关。

Li和Cs易富集在蛇纹岩中(Scambelluri et al., 2004; Deschamps et al., 2010; Lafay et al., 2013)。西南部印度洋脊蛇纹岩含0.1×10-6~19×10-6 Li (Decitre et al., 2002)。Lafay et al. (2013)报道的蛇纹岩中Li和Cs的含量分别为0.05×10-6~2.11×10-6、0.01×10-6~3.03×10-6。由橄榄石和辉石蚀变形成的蛇纹石对Li和Cs的富集是不同的 (Deschamps et al., 2010)。由橄榄石蚀变产生的蛇纹石中Li的含量为0.18×10-6~0.78×10-6,Cs的含量为从低于检出限到0.049×10-6;由辉石蚀变产生的蛇纹石含2.79×10-6~17.85×10-6 Li、0.037×10-6~0.194×10-6 Cs (Deschamps et al., 2010)。Li和Cs只在温度低于360℃时富集,在温度高于360℃的蛇纹岩中的含量低于检出限(Lafay et al., 2013)。

蛇纹石化过程中稀土元素几乎不活动(Scambelluri et al., 2001; Scambelluri et al., 2004)。Erro-Tobbio蛇纹石化的橄榄岩和蛇纹糜棱岩的稀土元素含量相似,这表明稀土元素的含量和蛇纹石化的程度以及压力的高低无关(Scambelluri et al., 2001)。蛇纹石化的地幔橄榄岩和科马提岩的稀土含量和未蚀变的超基性岩相似(O'Hanley, 1996)。单斜辉石的含量决定了稀土元素的多少。稀土元素在蛇纹石化过程中的不活动性可能是由于单斜辉石的蚀变较少。Scambelluri et al., 2001的研究表明,蛇纹石脉的稀土含量高,可能是因为脉中透辉石的含量高。然而,在蛇纹岩和石英闪长岩的接触带,富Ca-Mg(Mn)流体的交代作用形成异剥钙榴岩(rodingite),异剥钙榴岩的稀土元素含量高于蛇纹岩,低于石英闪长岩,其配分模式不同于蛇纹岩和石英闪长岩,而是蛇纹岩和石英闪长岩的混合(Leblanc and Lbouabi, 1988)。这说明矿物类型的变化可能会改变稀土元素的含量和配分模式。

赋存于蛇纹岩中的铁矿床是诸多铁矿床类型中较少的一类,例如意大利Aosta Valley铁矿床、摩洛哥Bou-Azzer蛇绿岩中的铁矿床、希腊北部Fe-Ni-Cr矿床等(Michailidis, 1990; Gahlan et al., 2006; Rossetti et al., 2009)。意大利Aosta Valley铁矿体中的磁铁矿含量约50%~60%,一种类型的磁铁矿分散在叶蛇纹石中,平均颗粒大小约200μm;另一种类型的磁铁矿分散在蛇纹石化的纯橄岩中,平均颗粒大小为1~2cm (Rossetti et al., 2009)。该矿床的成因备受争论,Zucchetti et al. (1988)认为矿化和早期海洋环境中的蛇纹石化有关,但Diella et al. (1994)则认为磁铁矿来源于含大量铬铁矿的矿体的蚀变。摩洛哥Bou-Azzer蛇绿岩中的磁铁矿细脉的宽度小于20cm,离铁矿近的蛇纹石化方辉橄榄岩含约4%的FeO,而离磁铁矿远的蛇纹石化方辉橄榄岩含约8% FeO,这表明铁矿中的Fe来自方辉橄榄岩(Gahlan et al., 2006)。希腊北部Fe-Ni-Cr矿床出现在蛇绿岩中,铬铁矿受到蛇纹石化产生的流体交代后其外围形成富磁铁矿的环带(Michailidis, 1990)。但相关的蛇纹石化实验表明,磁铁矿在蛇纹石中呈弥散状分布,大小约1~20μm (Malvoisin et al., 2012b)。当橄榄石全部蚀变时,只有约9.25%磁铁矿形成(Moody, 1976),如此少量的磁铁矿很难形成铁矿。但是,蛇纹石化实验是在封闭的体系中,温度和压力等外界条件相对均一,可能和开放的地质过程有所不同。

一般来说,镍的硫化物常以小颗粒分散在蛇纹岩中,这些矿物在蛇纹岩中的含量较低,且很少能发生富集,难以成为有经济价值的矿床(O'Hanley, 1996)。然而,仍有镍矿床的形成可能和蛇纹石化相关。例如,Dumont镍矿床赋存在蛇纹岩中,含0.4%~0.7%的镍,镍主要富集在硫化物中,典型的矿物组合包括铁镍矿(Ni3Fe)、镍纹石(Ni2Fe)、金属Fe、金属Ni、紫硫镍铁矿(FeNi2S4)和针镍矿(NiS)等(Eckstrand, 1975)。镍矿床中有两种典型的硫化物,一种占据橄榄石的粒间空隙,为圆形,其矿物组成为磁铁矿、铁镍矿或其他的含镍硫化物(几乎无铁硫化物);另一种是以细粒分散在蛇纹石中,颗粒大小约1~100μm,其矿物组成和第一种含镍硫化物相同,只在蛇纹石中出现而在新鲜未蚀变的橄榄石并未出现(Eckstrand, 1975)。

金在蛇纹石化产生的流体中是活动的。Buisson and Leblanc (1985)讨论了金矿化和滑石菱镁岩(listwanite)以及超基性围岩的关系,认为金来自于超基性岩的水热蚀变。水热溶液(含CO2和Ca)交代超基性岩形成滑石菱镁岩。金在滑石菱镁岩中较富集,高达1×10-6~10×10-6,而在超基性围岩中的含量为5×10-9~100×10-9,滑石菱镁岩中的黄铁矿(10×10-6~50×10-6 Au)和钴的砷化物(10×10-6~100×10-6 Au)是主要的赋金矿物(Buisson and Leblanc, 1985)。蛇纹石化过程中金的迁移和富集的过程如下:在岩浆过程中形成的Ni-Fe硫化物或者砷化物以副矿物的形式存在超基性岩中,早期的蛇纹石化流体呈酸性,可以溶解硫化物;金和溶液中的Cl、S和As形成络合物进行迁移,随着蛇纹石化的进行,体系的氧逸度降低,金沉淀并富集在磁铁矿和次生硫化物中;晚期的蛇纹石和磁铁矿发生碳酸盐化形成了滑石和碳酸盐矿物,此时金主要富集在硫化物或者砷化物中(Buisson and Leblanc, 1987)。另外,摩洛哥Bou Azzer含钴砷化物矿床位于蛇纹岩围岩的边部,金在钴矿体中的平均含量为5×10-6~20×10-6,金主要富集在方钴矿(CoAs3)中,含量高达1200×10-6,而斜方砷铁矿(FeAs2)的金含量极低,低于1×10-6 (Leblanc and Fischer, 1990)。

蛇纹岩中的Ag矿可能和蛇纹石化过程相关(Leblanc and Lbouabi, 1988)。Ag矿体主要包含自然银和Co-Fe砷化物。Ag的矿化发生在石英闪长岩和蛇纹岩的接触带,蛇纹岩是Ag的物质来源(Leblanc and Lbouabi, 1988)。

综上所述,蛇纹石化过程有待于深入研究,尤其是开展以下几个方面的实验工作有重要意义:

(1)高温(>400℃)和高压(>1GPa)下,蛇纹石化过程中磁铁矿的形成。这对俯冲过程中Fe的迁移和富集过程研究有重要意义。

(2)低温时(<300℃)蛇纹石化是否生成磁铁矿值得探讨。由于低温时蚀变较慢,实验周期较长,完全蚀变需要1年或更多的时间,故实验难度较大。

(3)纯橄岩、方辉橄榄岩、二辉橄榄岩和玄武岩蛇纹石化的比较。不同温度、压力条件下,由橄榄石蚀变产生的蛇纹石和由辉石蚀变产生的蛇纹石成分的差异,以及不同岩性岩石蚀变产物的对比值得关注。这有助于理解蛇纹石化过程的机理。

(4)稀土元素在蛇纹石化过程中的迁移。橄榄石、辉石和蛇纹石的稀土元素配分有何不同。和天然样品相比,实验样品条件简单,可被控制,这有助于了解蛇纹石化过程中稀土元素的迁移。

(5)不同温度、压力、反应溶液和水/岩比等条件下蛇纹石的Fe2+/Fe3+比值。目前为止,只有O'Hanley and Dyar, 1993对蛇纹石的Fe2+/Fe3+的比值进行了研究,但这些数据是由穆斯堡尔谱得到的,是很多蛇纹石颗粒的平均Fe2+/Fe3+比值,并不直接来自单颗蛇纹石。此外,Marcaillou et al. (2011)通过X射线吸收光谱得到了几乎完全蚀变了的橄榄岩的Fe3+/ΣFe比值,这仍然不是蛇纹石矿物的Fe3+/ΣFe,而是包含了蛇纹石、磁铁矿和少量未反应矿物的Fe3+/ΣFe。

(6)蛇纹石化过程中Cl的迁移、蛇纹石中Cl的含量以及Cl含量和蛇纹石化程度的关系。

致谢

本文修改过程中得到了彭少邦、胡永斌、郭冠华、丁伟等的帮助,在此表示诚挚的感谢。

| [1] | Allen DE and Seyfried WE Jr. 2003. Compositional controls on vent fluids from ultramafic-hosted hydrothermal systems at mid-ocean ridges: An experimental study at 400℃, 500bars. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 67(8): 1531-1542 |

| [2] | Anselmi B, Mellini M and Viti C. 2000. Chlorine in the Elba, Monti Livornesi and Murlo serpentinites: Evidence for sea-water interaction. European Journal of Mineralogy, 12: 137-146 |

| [3] | Bach W, Pualick H, Garrido CJ, Ildefonse B, Meurer WP and Humphris SE. 2006. Unraveling the sequence of serpentinization reactions: Petrography, mineral chemistry, and petrophysics of serpentinites from MAR 15°N (ODP Leg 209, Site 1274). Geophysical Research Letters, 33(13): L13306 |

| [4] | Beard JS, Frost BR, Fryer P, McCaig A, Searle R, Ildefonse B, Zinin P and Sharma SK. 2009. Onset and progression of serpentinization and magnetite formation in olivine-roch Troctolite from IODP hole U1309D. Journal of Petrology, 50(3): 387-403 |

| [5] | Belley F, Ferré EC, Martín-Hernández F, Jackson MJ, Dyar MD and Catlos EJ. 2009. The magnetic properties of natural and synthetic (Fex, Mg1-x)2SiO4 olivines. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 284(3-4): 516-526 |

| [6] | Berndt ME, Allen DE and Seyfried WE Jr. 1996. Reduction of CO2 during serpentinization of olivine at 300℃ and 500bar. Geology, 24(4): 351-354 |

| [7] | Bloomer SH. 1983. Distribution and origin of igneous rocks from the landward slopes of the Mariana Trench: Implications for its structure and evolution. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 88(B9): 7411-7428 |

| [8] | Bonifacie M, Busigny V, Mével C, Philippot P, Agrinier P, Jendrzejewski N, Scambelluri M and Javoy M. 2008. Chlorine isotopic composition in seafloor serpentinites and high-pressure metaperidotites: Insights into oceanic serpentinization and subduction processes. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 72(1): 126-139 |

| [9] | Buisson G and Leblanc M. 1985. Gold in carbonatized ultramafic rocks from ophiolite complexes. Economic Geology, 80(7): 2028-2029 |

| [10] | Buisson G and Leblanc M. 1987. Gold in mantle peridotites from Upper Proterozoic ophiolites in Arabia, Mali, and Morocco. Economic Geology, 82(8): 2091-2097 |

| [11] | Burkhard DJM. 1993. Accessory chromium spinels: Their coexistence and alteration in serpentinites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 57(6): 1297-1306 |

| [12] | Charlou JL, Fouquet Y, Bougault H, Donval JP, Etoubleau J, Jean-Baptiste P, Dapoigny A, Appriou P and Rona PA. 1998. Intense CH4 plumes generated by serpentinization of ultramafic rocks at the intersection of the 15°20'N fracture zone and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 62(13): 2323-2333 |

| [13] | Charlou JL, Donval JP, Fouquet Y, Jean-Baptiste P and Holm N. 2002. Geochemistry of high H2 and CH4 vent fluids issuing from ultramafic rocks at the Rainbow hydrothermal filed (36°14ˊN, MAR). Chemical Geology, 191: 345-359 |

| [14] | Coleman RG and Keith TE. 1971. A chemical study of serpentinization-Burro Mountain, California. Journal of Petrology, 12(2): 311-328 |

| [15] | Costa IRD, Barriga FJAS, Viti C, Mellini M and Wicks FJ. 2008. Antigorite in deformed serpentinites from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. European Journal of Mineralogy, 20(4): 563-572 |

| [16] | Decitre S, Deloule E, Reisberg L, James R, Agrinier P and Mével C. 2002. Behavior of Li and its isotopes during serpentinization of oceanic peridotites. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 3(1): 1-20 |

| [17] | Deschamps F, Guillot S, Godard M, Chauvel C, Andreani M and Hattori K. 2010. In situ characterization of serpentinites from forearc mantle wedges: Timing of serpentinization and behavior of fluid-mobile elements in subduction zones. Chemical Geology, 269(3-4): 262-277 |

| [18] | Diella V, Ferrario A and Rossetti P. 1994. The magnetite ore deposits of the southern Aosta Valley: Chromitite transformed during an alpine metamorphic event. Ofioliti, 19: 247-256 |

| [19] | Douville E, Charlou JL, Oelkers EH, Bienvenu P, Jove Colon CF, Donval JP, Fouquet Y, Prieur D and Appriou P. 2002. The rainbow vent fluids (36°N14'N, MAR): The influence of ultramafic rocks and phase separation on trace metal content in Mid-Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal fluids. Chemical Geology, 184(1-2): 37-48 |

| [20] | Dugan MA. 1979. A microprobe study of antigorite and some serpentine pseudomorphs. Canadian Mineralogist, 17: 771-784 |

| [21] | Eckstrand OR. 1975. The Dumont serpentinite: A model for control of nickeliferous opaque mineral assemblages by alteration reactions in ultramafic rocks. Economic Geology, 70(1): 183-201 |

| [22] | Evans BW, Kuehner SM and Chopelas A. 2009. Magnetite-free, yellow lizardite serpentinization of olivine websterite, Canyon Mountain complex, N.E. Oregon. American Mineralogist, 94(11-12): 1731-1734 |

| [23] | Evans BW. 2010. Lizardite versus antigorite serpentinite: Magnetite, hydrogen, and life. Geology, 38(10): 879-882 |

| [24] | Fisher RL and Engel CG. 1969. Ultramafic and basaltic rocks dredged from the nearshore flank of the Tonga trench. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 80(7): 1373-1378 |

| [25] | Foustoukos DI and Seyfried WE Jr. 2004. Hydrocarbons in hydrothermal vent fluids: The role of chromium-bearing catalysts. Science, 304(5673): 1002-1005 |

| [26] | Foustoukos DI, Savov IP and Janecky DR. 2008. Chemical and isotopic constraints on water/rock interactions at the Lost City hydrothermal field, 30°N Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 72(22): 5457-5474 |

| [27] | Frost BR and Beard JS. 2007. On silica activity and serpentinization. Journal of Petrology, 48(7): 1351-1368 |

| [28] | Fryer P, Ambos EL and Hussong DM. 1985. Origin and emplacement of Mariana forearc seamounts. Geology, 13(11): 774-777 |

| [29] | Gahlan HA, Arai S, Ahmed AH, Ishida Y, Abdel-Aziz YM and Rahimi A. 2006. Origin of magnetite veins in serpentinite from the Late Proterozoic Bou-Azzer ophiolite, Anti-Atlas, Morocco: An implication for mobility of iron during serpentinization. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 46(4): 318-330 |

| [30] | Golightly JP and Arancibia ON. 1979. The chemical composition and infrared spectrum of nickel and iron substituted serpentine from a nickeliferous laterite profile, Soroako, Indonesia. Canadian Mineralogist, 17: 719-728 |

| [31] | González-Mancera G, Ortage-Gutiérrez F, Proenza JA and Atudorei V. 2009. Petrology and geochemistry of Tehuitzingo serpentinites (Acarlán Complex, SW Mexico). Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, 61(3): 419-435 |

| [32] | Gunnarsson I, Arnórsson S and Jakobsson S. 2005. Precipitation of poorly crystalline antigorite under hydrothermal conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 69(11): 2813-2828 |

| [33] | Hattori KH and Guillot S. 2003. Volcanic fronts as a consequence of serpentinite dehydration in the mantle wedge. Geology, 31(6): 525-528 |

| [34] | Hattori K, Takahashi Y, Guillot S and Johanson B. 2005. Occurrence of arsenic (V) in forarc mantle serpentinites based on X-ray absorption spectroscopy study. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 69(23): 5585-5596 |

| [35] | Horita J and Berndt ME. 1999. Abiogenic methane formation and isotopic fractionation under hydrothermal conditions. Science, 285(5430): 1055-1057 |

| [36] | Hyndman RD and Peacock SM. 2003. Serpentinization of the forearc mantle. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 212(3-4): 417-432 |

| [37] | Iishi K and Saito M. 1973. Synthesis of antigorite.American Mineralogist, 58: 915-919 |

| [38] | Janecky DR and Seyfried WE. 1986. Hydrothermal serpentinization of peridotite within the oceninc crust: Experimental investigations of mineralogy and major element chemistry. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 50(7): 1357-1378 |

| [39] | Ji FW, Zhou HY and Yang QH. 2008. The abiotic formation of hydrocarbons from dissolved CO2 under hydrothermal conditions with cobalt-bearing magnetite. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres, 38(2): 117-125 |

| [40] | Kelley DS, Karson JA, Blackman DK, FrÜh-Green GL, Butterfield DA, Lilley MD, Olson EJ, Schrenk MO, Roe KK, Lebon GT, Rivizzigno P and the AT3-60 Shipboard Party. 2001. An off-axis hydrothermal vent field near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at 30°N. Nature, 412: 145-149 |

| [41] | Kodolányi J, Pettke T, Spandler C, Kamber BS and Gméling K. 2012. Geochemistry of ocean floor and fore-arc serpentinites: Constraints on the ultramafic input to subduction zones. Journal of Petrology, 53(2): 235-270 |

| [42] | Lafay R, Montes-Hernandez G, Janots E, Chiriac R, Findling N and Toche F. 2012. Mineral replacement rate of olivine by chrysotile and brucite under high alkaline conditions. Journal of Crystal Growth, 347(1): 62-72 |

| [43] | Lafay R, Deschamps F, Schwartz S, Guillot S, Godard M, Debret B and Nicollet C. 2013. High-pressure serpentinites, a trap-and-release system controlled by metamorphic conditions: Example from the Piedmont zone of the western Alps. Chemical Geology, 343: 38-54 |

| [44] | Lazar C, McCollom TM and Manning CE. 2012. Abiogenic methanogenesis during experimental komatⅡte serpentinization: Implications for the evolution of the Early Precambrian atmosphere. Chemical Geology, 326-327(9): 102-112 |

| [45] | Leblanc M and Lbouabi M. 1988. Natice silver mineralization along a rodingite tectonic contact between serpentinite and quartz diorite (Bou Azzer, Morocco). Economic Geology, 83(7): 1379-1391 |

| [46] | Leblanc M and Fischer W. 1990. Gold and platinum group elements in cobalt-arsenide ores: Hydrothermal concentration from a serpentinite source-rock (Bou Azzer, Morocco). Mineralogy and Petrology, 42(1-4): 197-209 |

| [47] | Maekawa H, Yamamoto K, Teruaki I, Ueno T and Osada Y. 2001. Serpentinite seamounts and hydrated mantle wedge in the Izu-Bonin and Mariana forearc regions. Bull. Earthq. Res. Inst. Univ.Tokyo, 76: 355-366 |

| [48] | Malvoisin B, Carlut J and Brunet F. 2012a. Serpentinization of oceanic peridotites: 1. A high sensitivity method to monitor magnetite production in hydrothermal experiments. Journal of Geophysical Research, 117: B01104, doi:10.1029/2011JB008612 |

| [49] | Malvoisin B, Brunet F, Carlut J, Roumejon S and Cannat M. 2012b. Serpentinization of oceanic peridotites: 2. Kinetics and processes of San Carlos olivine hydrothermal alteration. Journal of Geophysical Research, 117: B04102, doi:10.1029/2011JB008842 |

| [50] | Marcaillou C, Muñoz M, Vidal O, Parra T, Harfouche M. 2011. Mineralogical evidence for H2 degassing during serpentinization at 300℃/300bar. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 303(3-4): 281-290 |

| [51] | Martin B and Fyfe WS. 1970. Some experimental and theoretical observations on the kinetics of hydration reactions with particular reference to serpentinization. Chemical Geology, 6: 185-202 |

| [52] | McCollom TM and Bach W. 2009. Thermodynamic constraints on hydrogen generation during serpentinization of ultramafic rocks. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 73(3): 856-875 |

| [53] | McCollom TM and Seewald JS. 2001. A reassessment of the potential for reduction of dissolved CO2 to hydrocarbons during serpentinization of olivine. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 65(21): 3769-3778 |

| [54] | Mellini M, Rumori C and Viti C. 2005. Hydrothermally reset magmatic spinels in retrograde serpentinites: Formation of "ferritchromit" rims and chlorite aureoles. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 149(3): 266-275 |

| [55] | Menzies MA, Long A, Ingram G, Tatnel M and Janecky D. 1993. MORB-peridotite-sea water interaction: Experimental constraints on the behavior of trace elements, 87Sr/86Sr and 143Nd/144Nd ratios. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 76(1): 309-322 |

| [56] | Mével C. 2003. Serpentinization of abyssal peridotites at mid-ocean ridges. Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 335(10-11): 825-852 |

| [57] | Michailidis KM. 1990. Zoned chromites with high Mn-contents in the Fe-Ni-Cr-laterite ore deposits from the Edessa area in Northern Greece. Mineralium Deposita, 25(3): 190-197 |

| [58] | Moody JB. 1976. An experimental study of the serpentinization of iron-bearing olivines. Canadian Mineralogist, 14: 462-478 |

| [59] | Nordstrom DK. 2002. Worldwide occurrences of arsenic in ground water. Science, 296(5576): 2143-2145 |

| [60] | Normand C, Willilams-Jones AE, Martin RF and Vali H. 2002. Hydrothermal alteration of olivine in a flow-through autoclave: Nucleation and growth of serpentine phases. American Mineralogist, 87(11-12): 1699-1709 |

| [61] | O'Hanley DS and Dyar MD. 1993. The composition of lizardite 1T and the formation of magnetite in serpentinites. American Mineralogist, 78: 391-404 |

| [62] | O'Hanley DS. 1996. Serpentinites: Records of Tectonic and Petrological History. New York: Oxford University Press |

| [63] | Okamoto A, Ogasawara Y, Ogawa Y and Tsuchiya N. 2011. Progress of hydration reactions in olivine-H2O and orthopyroxenite-H2O systems at 250℃ and vapor-saturated pressure. Chemical Geology, 289(3-4): 245-255 |

| [64] | Proskurowski G, Lilley MD, Seewald JS, FrÜh-Green GL, Olson EJ, Lupton JE, Sylva SP and Kelley DS. 2008. Abiogenic hydrocarbon production at Lost City hydrothermal field. Science, 319(5863): 604-606 |

| [65] | Rossetti P, Gatta GD, Diella V, Carbonin S, Giusta AD and Ferrario A. 2009. The magnetite ore districts of the southern Aosta Valley (Western Alps, Italy): A mineralogical study of metasomatized chromite ore. Mineralogical Magazine, 73(5): 737-751 |

| [66] | Saumur BM and Hattori K. 2013. Zoned Cr-spinel and ferritchromite alteration in forearc mantle serpentinites of the Rio San Juan Complex, Dominican Republic. Mineralogical Magazine, 77(1): 117-136 |

| [67] | Scambelluri M, Rampone E and Piccardo GB. 2001. Fluid and element cycling in subducted serpentinite: A trace-element study of the Erro-Tobbio high-pressure ultramafites (western Alps, NW Italy). Journal of Petralogy, 42(1): 55-67 |

| [68] | Scambelluri M, Fiebig J, Malaspina N, MÜntener O and Pettke T. 2004.Serpentinite subduction: Implications for fluid processes and trace-element recycling. International Geology Review, 46(7): 595-613 |

| [69] | Schmidt K, Koschinsky A, Garbe-Schnberg D, Carvalho LM and Seifert R. 2007. Geochemistry of hydrothermal fluids from the ultramafic-hosted Logatchev hydrothermal field, 15°N on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge: Temporal and spatial investigation. Chemical Geology, 242(1-2): 1-21 |

| [70] | Schmidt MW and Poli S. 1998. Experimentally based water budgets for dehydrating slabs and consequences for arc magma generation. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 163(1-4): 361-379 |

| [71] | Schrenk MO, Brazelton WJ and Lang SQ. 2013. Serpentinization, carbon, and deep life. Review in Mineralogy & Geochemistry, 75(1): 575-606 |

| [72] | Seyfried WE Jr and Dibble WE Jr. 1980. Seawater-peridotite interaction at 300℃ and 500bars: Implications for the origin of oceanic serpentinites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 44(2): 309-321 |

| [73] | Seyfried WE Jr and Bischoff JL. 1981. Experimental seawater-basalt interaction at 300℃, 500bars, chemical exchange, secondary mineral formation and implications for the transport of heavy metals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 45: 135-147 |

| [74] | Seyfried WE Jr, Foustoukos DI and Fu Q. 2007. Redox evolution and mass transfer during serpentinization: An experimental and theoretical study at 200℃, 500bar with implications for ultramafic-hosted hydrothermal systems at Mid-Ocean Ridges. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 71(15): 3872-3886 |

| [75] | Uehara S and Shirozu H. 1985. Variations in chemical composition and structural properties of antigorites. Mineralogical Journal, 12(7): 299-318 |

| [76] | Ulmer GC. 1974. Alteration of chromite during serpentinization in the Pennsylvania-Maryland district. American Mineralogist, 59: 1236-1241 |

| [77] | Ulmer P and Trommsdorff V. 1995. Serpentine stability to mantle depths and subduction-related magmatism. Science, 268(5212): 858-861 |

| [78] | Wang JA, Novaro O, Bokhimi X, López T, Gómez R, Navarrete J, LIanos ME and López-Salinas E. 1998. Characterizations of the thermal decomposition of brucite prepared by sol-gel technique for synthesis of nanocrystallize MgO. Materials Letters, 35(5-6): 317-323 |

| [79] | Wang XM, Zeng ZG and Chen JB. 2009. Serpentinization of peridotite in the Mariana Arc. Progress in Natural Science, 19(8): 859-867 (in Chinese) |

| [80] | Wang YR, Fan WL and Yu YM. 1981. Geochemical mechanism of alkali metasomatism and the formation of iron deposits. Geochimica, (1): 95-102 (in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [81] | Wunder B, Wirth R and Gottschalk M. 2001. Antigorite: Pressure and temperature dependence of polysomatism and water content. European Journal of Mineralogy, 13(3): 485-495 |

| [82] | Zucchetti S, Mastrangelo F, Rossetti P and Sandrone R. 1988. Serpentinization and metamorphism: Their relationships with metallogeny in some ophiolitic ultramafics from the Alps. In: Zuffar' Days Symposium in Honor of Piero Zuffardi. Cagliari: University of Cagliari, 137-159 |

| [83] | 汪小妹, 曾自刚, 陈俊兵. 2009. 马里亚纳前弧南部橄榄岩的蛇纹石化. 自然科学进展, 19(8): 859-867 |

| [84] | 王玉荣, 樊文苓, 郁云妹. 1981. 碱交代与铁矿形成的地球化学机理探讨. 地球化学, (1): 95-102 |

2013, Vol. 29

2013, Vol. 29