Jianrong Ma is a professor, chief and Master’s supervisor of the Neurosurgery Department at Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Dr. Ma graduated from Hunan Medical College with BS degree in 1982 and obtained his PhD (Neurosurgery) degree from Hunan Medical College in 1990. He was the editor of Chinese Journal of Otorhinolaryngologic and Skull Base Surgery and Journal of International Neurology and Neurosugery. He carried out the “ischemic preconditioning on cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury of protection mechanism research (1991)” and won second Award for Science and Technology Progress of Hunan Province and the third prize of Medical Science and Technology and Third Award for Medical Science and Technology of Hunan Province. He experts in surgical treatment of complicated aneurysm, giant arteriovenous malformation and skull base tumor. His major interests and research studies focus on surgical treatment of cerebrovascular diseases..

Yiwei Liao is an attending of the Neurosurgery Department at Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Dr. Liao graduated from Xiangya Medical School of Central South University with Master degree in 2007 and obtained his PhD (Neurosurgery) degree from Xiangya Medical School of Central South University in 2009. He also was visiting scholar of Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 2016. He has published 5 SCI papers in recent 5 years. His major interests and research studies focus on surgical treatment of cerebrovascular diseases..

Cavernous malformation (CM) originated from brain stem is a rare vascular disease in the population, with the constitution of 0.01%-0.05%[1-5]. By the reason of eloquent locations, brainstem cavernous malformations (BSCMs)[6, 7] present prodigious microsurgical challenge for neurosurgeons, with high morbidity and mortality. Although the decision of surgical resection should be prudently made, there is no doubt that surgical resection has been considered as the optimal choice for the symptomatic and hemorrhagic BSCMs[2, 8]. Brain stem is anatomically divided into three parts: midbrain, pons and medulla. The existing problem is that no single approach can expose the whole area of brainstem. Usually, we advocate tailoring surgical approach personally according to the lesion. BSCMs are different from CMs in other parts of brain in that the surrounding cranial nerves, brainstem nuclei and fibrous tracts are challenging for neurosurgeons to deal with[4, 9-11]. There are numerous approaches to handle BSCMs, which can be generally divided into three types: anterior, lateral and posterior approach. The anterior approaches mainly include pterional, orbitozygomatic and transoral. The lateral approaches mainly include subtemporal, Kawase and presigmoid approach. The posterior approach handling BSCMs mainly include infratentorial approach, midline suboccipital with or without telovelar, retrosigmoid approach and far lateral approach. In this article, we summarized our experience in treatment and choice of surgical approach of BSCM, and reviewed the recent relevant articles, to discuss the advance of surgical treatments of brain stem cavernous malformation.

2 Patients and methodsFrom May 1, 2014 to April 30, 2016, 20 consecutive patients underwent operations in order to resect brainstem cavernous malformations. Of these patients, 10 were men and 10 women, with a mean age of 38.5 years (SD 10.4 years; range, 20-52 years). All those patients were surgically treated by our senior doctor (J. R. Ma) in Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. The inpatient, clinical, and surgical records, radiologic imaging and follow-up data were reviewed.

All the patients were evaluated preoperatively with Magnetic Resonace Imaging (MRI) examination. Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) was performed in 5 cases, and digital subtract angiography (DSA) in 3 cases. The volume of the lesions was calculated by estimating the volume of an ellipsoid. The simplified formula (1/2 × sagittal diameter × coronal diameter × axial diameter) was used in calculating the volume after measurement in MRI.

The follow-up information mainly came from two parts: outpatient physical examination, and phone call contacting patients and their relatives. The follow-up time ranged from 2 months to 20 months (mean 9.5 months, SD 6.6 months). Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) was used to evaluate patients' states both pre-and postsurgery[12, 13].

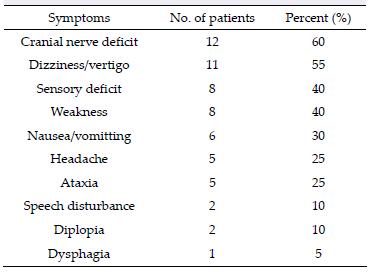

3 Clinical presentation and diagnosisThere is significant difference between BSCMs and CMs located in other parts of brain in signs and symptoms. Almost all of the patients (20 patients) had a sudden onset of focal neurological deficits. Typical symptoms of those patients include hemianesthesia or hemiparesis and either dizziness, headache, nausea, or vertigo. Common symptoms are showed on Table 1. The most common symptoms of those patients are cranial nerve deficits (60%) and dizziness or vertigo (55%).

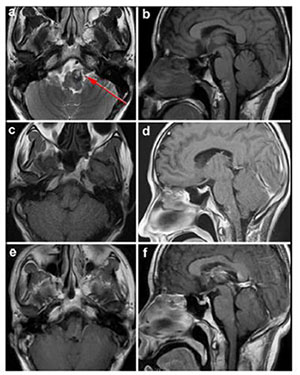

MRI is the most necessary examination for BSCMs in terms of diagnosis and differential diagnosis. CTA and DSA play important roles in distinguishing CMs with AVMs. Because of hemorrhage, typical imaging appearances of BSCMs are hyperintense core (methemoglobin) surrounded by hypointense rim (hemosiderin) on both T1-and T2-weighted MRI (Figure 1). Gradient-echo scan, especially susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI), can be used to find small occult lesions. CTA or DSA generally failed to reveal the BSCMs because of lacking feeding arteries.

|

| Figure 1 MRI demonstrated the typical "porpcorn" or "mulberry-like" BSCMs. (a), (b) and (c) showed one patient with pontine cavernoma. (d), (e) and (f) showed another patient with left cerebellar peduncle cavernoma. (a) and (d) axial T1-weighted, (b) and (e) axial T2-weighted, (c) axial enhanced T1-weighted, (f) SWI. |

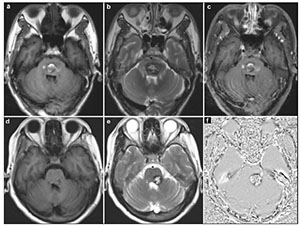

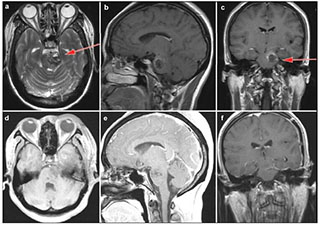

The surgical approach was designed according to the neurological examination and MRI (including diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), Figure 2). The 2-point method advocated by Spetzler and co-authors was employed in selecting surgical approaches[5, 7, 14, 15]. All the lesions were resected under electrophysiological monitoring including motor-evoked potential, somatosensoryevoked potential, and brainstem auditory-evoked potential. All of the operations were performed in park bench positions or supine positions. Totally, we applied the following 3 basic skull base approaches in handling the 20 BSCMs: midline suboccipital approach (14 patients), retrosigmoid approach (3 patients), and subtemporal approach (3 patients). As our experience with BSCMs has enriched, we advocate using simple and protective approaches instead of complex and invasive approaches. Spetzler et al. proposed that almost any BSCMs can be exposed adequately with one of the following basic skull base approaches or their variations: retrosigmoid, far lateral, midline suboccipital with or without telovelar, orbitozygomatic, and supracerebellar-infratentorial. We truly agree with their opinion but we believe that subtemporal approach could be performed in a minimally invasive way with lumbar drainage and protection of vein of Labbé.

|

| Figure 2 The surgical approach designed with the aid of DTI. T1-weighted (a) showed the lesion located in the right side of pontine. The three dimensional DTI (b) showed that the anterior and posterior side of the lesion was surrounded by tracts. The right approach to resect this lesion should be from the lateral side (we chose subtemporal approach). |

According to MRI findings and symptoms of the patients, sixteen (80%) symptomatic patients underwent surgery after first bleeding episode within 3 months; four patients (20%) underwent surgery after two or more bleeding episodes. The localization of the BSCMs included one in midbrain, eleven in pons and two in medulla oblongata. Six BSCMs were large enough to implicate adjacent area: including three pontomesencephalic and three medullary-pontine. The mean volume of these lesions was 3.15 cm3, with a standard deviation of 3.33 cm3. A total of 20 operative procedures were performed for the 20 patients without surgical related mortality. The postoperative MRI within 72 hours demonstrated that all the lesions were completely removed.

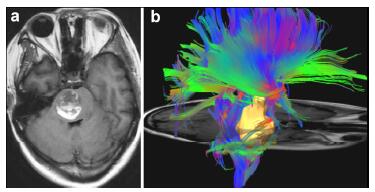

Case 1: A 21-year-old woman presented with acute onset of headache, vertigo, nausea, and vomiting; right hemibody numbness and weakness (2/5); ataxia; mRS 4. The CM was located in the centre of pons (Figure 3). We approached the lesion by a midline suboccipital with telovelar approach. At 17 months follow-up, the patient has improved numbness and weakness (4/5) on the right but slight ataxia and facial droop on the left, mRS 2.

|

| Figure 3 Case 1: Central pontine cavernous malformation. Axial gradient-echo image (a), enhanced T1-weighted postoperative with 72 hours (b) and enhanced T1-weighted postoperative scans at 3 month (c). White arrow showed the entry point. |

Case 2: A 40-year-old man was admitted to hospital because of right hemibody weakness (4/5), mRS 2. He was found to have a left anterolateral medullary hemorrhage as a result of underlying CM (Figure 4). A left retrosigmoid approach was applied to gain access to the lateral medulla oblongata, where the cavernous malformation was observed to come to the surface. When he was discharged, the right hemibody weakness (3/5) was slightly worsened. At 5 months' follow up, the patient had completely recovered and returned to work, mRS 0.

|

| Figure 4 Case 2: Left anterolateral medullary cavernous malformation. Axial T2-weighted (a) and sagital T1-weighted (b) showed the location of the lesion. Axial T1-weighed (c) and enhanced sagittal T1-weighted (d) postoperative within 72 h showed that the lesion was totally resected. Enhanced axial T1-weighted (e) and enhanced sagittal T1-weighted (f) at 5-month postoperative follow-up. Red arrow showed the entry approach (retrosigmoid approach). |

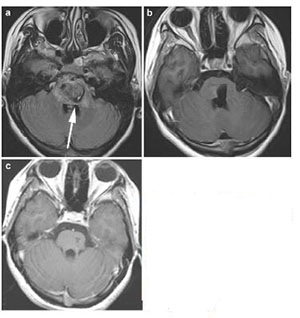

Case 3: A 30-year-old woman developed acute onset of headache, right hemibody weakness (4/5), mRS 2. Because of her CM located in the left pons and lower midbrain, a left subtemporal approach was performed (Figure 5). She developed slightly worsening of her right hemibody weakness (3/5) postoperatively. At 2 months' follow up, the patient had improved her right hemibody weakness, mRS 1.

|

| Figure 5 Case 3: Cavernous malformation in the left pons and lower midbrain. T2-weighted (a), enhanced sagittal T1-weighted (b) and enhanced coronal T1-weighted (c) demonstrated the location of the cavernous malformation. Enhanced axial T1-weighted (d) and sagittal T1-weighted (e) postoperative within 72 hours showed that the lesion was totally resected. Enhanced coronal T1-weighted (f) showed no recurrence after 3 months follow-up. Red arrow showed the entry approach (subtemporal approach). |

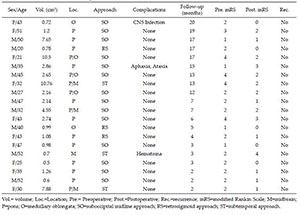

The Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score was used to evaluate the preoperative and postoperative clinical status. At the mean follow-up time of 9.5 months (2-20 months), the mean mRS score improved from 2.25 (preoperative) to 1.40. Compared with the preoperative mRS score, fifteen patients had improved, three patients unchanged, and two patients deteriorated. Therefore, 90% (18/20) of the patients were better or the same at their last follow-up examination. The follow-up information is listed in Table 2.

|

The annual hemorrhage rates of BSCMs ranged from 2.3% to 4.1% in studies of the natural history of the malformations[1, 15-17]. After the first hemorrhage, however, the risk of further bleeding is increased from 4.5% to 40% annually[18-21]. In considering that the high morbidity and mortality after first hemorrhage and the much increased re-hemorrhage rate, the microsurgery intervention should be planned for the symptomatic and hemorrhagic BSCMs. In recent years, technological advances, including MRI-guided navigation, neurophysiological monitoring and endoscopic techniques, have already changed the surgical manner of handling BSCMs[8]. We will discuss how to plan an appropriate approach with adequate exposure of BSCMs and how to remove the BSCM in a minimally invasive manner.

7.1 ApproachesAs we have mentioned, we advocate abandoning the skull base approaches with high rates of morbidity, such as Kawse approach and presigmoid approach. We hold that most of the BSCMs can be adequately exposed and successfully resected with following approaches: midline suboccipital with or without telovelar approach, retrosigmoid approach, and subtemporal approach. Only a small part of BSCMs located in interpeduncle fossa, quadrigeminal area and lower medulla, need orbitozygomatic, supracerebellar infratentorial and far lateral approach. For a few BSCMs located in ventrolateral pons, pterional transsylvian transtentorial approach is a wise choice.

7.1.1 Midline suboccipital with or without telovelar approachMidline suboccipital with or without telovelar approach is the main approach we used in this series. We prefer park bench positions when we perform this approach. With careful division of tela choroidea and inferior medullary velum, it can provide access to the entire floor of the fourth ventricle up to the aqueduct. In most cases, with the underlying risk of postoperative truncal ataxia, the resection of vermis is not necessary[22]. For the uppermost part of the fourth ventricle lesions, we needed additional exposure by splitting a small portion of the inferior vermis. Giliberto et al. concluded the safe entry zones: the median sulcus above the facial colliculus, the suprafacial triangle, and the infrafacial triangles[23]. We hold that only the BSCM or hemorrhage which can be visible on the floor of fourth ventricle should be excised by means of this approach. In the exceptional lesions, the entry point should be ensured with the aid of DTI, MRI-guided navigation, and neurophysiological monitoring.

7.1.2 Subtemporal approachSubtemporal approach is used in three cases of this series. All three patients were positioned supine with the head rotated toward the contralateral side of the lesion (the sagittal suture parallel to the floor), and the shoulder was elevated with a sandbag on the operative side in order to minimize excessive rotation of the neck. The lumbar drainage should be placed to release CSF and reduce the temporal lobe retraction. Frontotemporal or temporal craniotomy should be achieved to expose middle fossa base. Vein of Labbé was an important landmark and should be protected carefully. We always chose the surgical route in front of the vein by means of neuronavigation (also called anterior temporal approach). After finding the CN Ⅳ entry point, an incision should be made medial to CN Ⅳ. An area of lateral peduncle and pons, inferior to posterior root of CN Ⅴ, and medial to the basilar artery can be achieved. This approach can't expose the area below the posterior root of CN Ⅴ, which can be exposed through retrosigmoid approach. Šteňo et al. had used the electrical stimulation technique for detection of the topography of pyramidal tract. They reported 9 cases of CMs located in the upper pons and mesencephalon, and by means of this technique they achieved an excellent result[24]. Rigante et al. had described this approach with ten cases and achieved a remarkable outcome with the aid of neuronavigation[25].

7.1.3 Retrosigmoid approachRetrosigmoid approach was also used in another three cases of this series. The three patients adopted park bench position. We adopted inverted "L-type" skin incision behind the auricle instead of straight or "S-type" skin incision. We believe that this incision is helpful in exposing the deeper and lower lesions. The bone window should be enough to expose the edge of transverse and sigmoid sinuses. The lower edge of the bone window could be adjusted according to the size and location of the lesion. The CN Ⅳ down to the CN XI can be exposed. Lesions of the lateral pons, pontomedullary junction and upper medulla can be resected through this approach. The well-described safety entry zone "peritrigeminal area" located medially to the CN Ⅴ and laterally to the pyramidal tract[23, 26]. Wang et al. reported a large surgical series of pontine cavernomas; and they got a good result with retrosigmoid approach[27].

7.1.4 Other approachesOrbitozygomatic approach is used to expose the anterior and lateral midbrain, interpeduncular fossa, rostral pons and pontomesencephalic junction. We didn't use this approach handling BSCMs in this series, but we often used this approach handling middle fossa base meningomas, Schwannomas, and basilar apex aneurysms. The main complications of this approach include temporary or permanent paresis of frontalis muscle, temporary orbital swelling, enophthalmos of an entrapped globe, cranial neuropathy, and leakage of CSF. Spezler et al. described a large series of BSCMs with 300 patients in 2010. They applied this approach in 18 patients and they achieved a remarkable outcome[5]. More recently, Sekhar et al. reported 22 patients with BSCMs and applied this approach in 5 patients. 4 patients improved in their mRS score; one patient remained, and none reduced[28].

Supracerebellar infratentorial (SCIT) approach has three variant: the median, paramedian, and lateral. BSCMs located on the posterolateral surface of the upper pons and midbrain can be reached through one of the SCIT approaches. The choice of approach depends on the best trajectory between the most superficial point of the lesion and the surface of the cranium ("two points" principle)[15]. In a large series of 300 BSCM patients, they applied the SCIT approach in more than 20% of adult patients[5]. De Oliveira et al. described this approach in detail with 45 BSCM patients. They concluded the indications, techniques, complications, and outcomes of the SCIT approach and its variants[15]. However, we didn't use this approach in this series. The reason can be concluded in two aspects: there was no lesion located in dorsal midbrain in this series and we chose midline suboccipital approach and retrosigmoid approach to resect lesions located in the posterolateral surface of the upper pons.

Far lateral approach was only used in a small part of BSCM patients. This approach can expose inferolateral pons and anterolateral medulla. We used this approach to manage the vertebral aneurysms and lower clival meningiomas. By opening the foramen magnum, the retrosigmoid approach can reach most area of lateral medulla. This was the reason why we rarely used far lateral approach in handling BSCMs. However, Lawton et al. modified this approach and developed the far lateral transpontomedullary sulcus approach (TPMS) to access the deep pontine lesions. They reported four patients underwent this approach and they achieved good outcomes (mRS score ≤2, three patients improved or unchanged) in all patients[29].

The pterional transsylvian approach was proposed by Yarsargil[30] in order to manage aneurysms. With dissection of tentorium edge medially to the CN Ⅳ entry point, the ventrolateral pons can be exposed. Many clinical studies showed this approach is effective and can achieve remarkable outcomes in handling pontine CMs[2, 3, 31]. Most recently, Bao et al. described this approach with four impressive cases and concluded that the exposure of the upper ventral pons around the CN Ⅳ entry zone can be achieved[31].

7.2 Minimally invasive but maximally effective techniquesThe preoperative planning should be made carefully, having decided to proceed with resection. How to choose the proper approach to reach the lesion was the first problem. A proper approach not only can expose the lesion sufficiently, but also brings a lower rate of morbidity. When tailoring the approach of the BSCM, the two-point method and the safety entry point should be taken into consideration. When the lesion doesn't come to the pial surface, DTI is helpful in identifying the fiber tracts surrounding the lesion bilaterally.

MRI-guided navigation and neurophysiological monitoring are effective techniques during the operation of BSCMs. For the small or deep lesions, navigation plays an important role in finding minimally invasive corridors accessing the lesions. Brain shift after brain retraction and releasing CSF can impact the accuracy of navigation. So, localization of small or deep lesions should be made before large retraction of brain and releasing a large amount of CSF. We advocate monitoring motor-evoked potentials, somatosensoryevoked potentials, and brainstem auditory-evoked potentials in all BSCM patients.

Once the lesion has been accessed through a small corridor, manipulation should be strictly limited within the lesion. The cavernoma should always be resected piece by piece, initially from the central part of cavernoma. Unlike CMs in other parts of brain, the venous anomalies associated with BSCMs and hemosiderin-stained brain tissue should be preserved[5, 32, 33].

Sufficient dissection of arachnoid membrane and cisterns can enlarge the operational room and reduce retraction of the brain tissue. After dissecting cerebellomedullary fissure and inferior medullary velum in the telovelar approach to brainstem, the whole fourth ventricle can be exposed without splitting the vermis[22, 33]. In the retrosigmoid approach, releasing CSF from the cisterna magna or cerebellopotine cistern can relax the cerebellum and reduce retraction.

7.3 EndoscopyWith the development of endoscopic technique, a few surgeons are trying to resect BSCMs under endoscopy combined with the aid of MRI-guided navigation. Under the endoscopy, there was no difficulty in accessing the whole area of anterior side of brainstem. One of the advantages of endoscopy is that it can deliver the operative focus to the area between cranial nerves. The prominent problem is that how to prevent CSF leakage after operation. Endoscopic endonasal transclival approach resecting ventral pontine CMs was applied in several cases and achieved amazing outcomes[16, 22, 34]. We believe that endoscopy will become an important manner in resecting BSCMs with the development of endoscopic manipulation and skull base reconstruction technique.

8 ConclusionThe three common basic skull base approaches, combined with minimally invasive but maximally effective techniques can handle most of BSCMs with good surgical results. MRI-guided navigation and neurophysiological monitoring are essential during operation. Endoscopy will be an important manner in resecting BSCMs. The familiar and less invasive skull base approaches will replace the invasive and complex skull base approaches in handling the BSCMs and we conclude the minimally invasive basic skull base approaches to access the BSCMs.

Conflict of interests

All contributing authors have no conflict of interests.

| [1] | Cantu C, Murillo-Bonilla L, Arauz A, Higuera J, Padilla J, Barinagarrementeria F. Predictive factors for intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with cavernous angiomas. Neurol Res, 2005, 27(3): 314–318. DOI:10.1179/016164105X39914 |

| [2] | Chen L, Zhao Y, Zhou L, Zhu W, Pan Z, Mao Y. Surgical strategies in treating brainstem cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery, 2011, 68(3): 609–620. DOI:10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182077531 |

| [3] | Gross BA, Batjer HH, Awad IA, Bendok BR, Du R. Brainstem cavernous malformations:1390 surgical cases from the literature. World Neurosurg, 2013, 80(1-2): 89–93. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2012.04.002 |

| [4] | Kim DS, Park YG, Choi JU, Chung SS, Lee KC. An analysis of the natural history of cavernous malformations. Surg Neurol, 1997, 48(1): 9–17. DOI:10.1016/S0090-3019(96)00425-9 |

| [5] | Abla AA, Lekovic GP, Turner JD, de Oliveira JG, Porter R, Spetzler RF. Advances in the treatment and outcome of brainstem cavernous malformation surgery:A single-center case series of 300 surgically treated patients. Neurosurgery, 2011, 68(2): 403–414. DOI:10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181ff9cde |

| [6] | El Ahmadieh TY, Aoun SG, Bendok BR, Batjer HH. Management of brainstem cavernous malformations. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med, 2012, 14(3): 237–251. DOI:10.1007/s11936-012-0181-x |

| [7] | Gross BA, Batjer HH, Awad IA, Bendok BR. Brainstem cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery, 2009, 64(5): E805–818. DOI:10.1227/01.NEU.0000343668.44288.18 |

| [8] | Abla AA, Spetzler RF. Brainstem cavernoma surgery:The state of the art. World Neurosurg, 2013, 80(1-2): 44–46. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2012.06.011 |

| [9] | Bogucki J, Czernicki Z, Gielecki J. Cytoarchitectonic basis for safe entry into the brainstem. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2000, 142(4): 383–387. DOI:10.1007/s007010050446 |

| [10] | Kumar A, Sharma R, Garg A, Sharma BS. Contralateral anterior interhemispheric transparaterminal gyrus approach for thalamopeduncular pilocytic astrocytoma in an adult:Technical report. World Neurosurg, 2016, 87: 21–25. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.09.021 |

| [11] | Recalde RJ, Figueiredo EG, de Oliveira E. Microsurgical anatomy of the safe entry zones on the anterolateral brainstem related to surgical approaches to cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery, 2008, 62(3 Suppl 1): 9–15. |

| [12] | Francois P, Ben Ismail M, Hamel O, Bataille B, Jan M, Velut S. Anterior transpetrosal and subtemporal transtentorial approaches for pontine cavernomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2010, 152(8): 1321–1329. DOI:10.1007/s00701-010-0667-9 |

| [13] | Rankin J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60. Ⅲ. Diagnosis and treatment. Scott Med J, 1957, 2(6): 254–268. |

| [14] | Abla AA, Lekovic GP, Garrett M, Wilson DA, Nakaji P, Bristol R, Spetzler RF. Cavernous malformations of the brainstem presenting in childhood:Surgical experience in 40 patients. Neurosurgery, 2010, 67(6): 1589–1598. DOI:10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181f8d1b2 |

| [15] | de Oliveira JG, Lekovic GP, Safavi-Abbasi S, Reis CV, Hanel RA, Porter RW, Preul MC, Spetzler RF. Supracerebellar infratentorial approach to cavernous malformations of the brainstem:surgical variants and clinical experience with 45 patients. Neurosurgery, 2010, 66(2): 389–399. DOI:10.1227/01.NEU.0000363702.67016.5D |

| [16] | Sanborn MR, Kramarz MJ, Storm PB, Adappa ND, Palmer JN, Lee JY. Endoscopic, endonasal, transclival resection of a pontine cavernoma:case report. Neurosurgery, 2012, 71(1 Suppl Operative): 198–203. |

| [17] | Chen LH, Zhang HT, Chen L, Liu LX, Xu RX. Minimally invasive resection of brainstem cavernous malformations:Surgical approaches and clinical experiences with 38 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg, 2014, 116: 72–79. DOI:10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.10.012 |

| [18] | Aiba T, Tanaka R, Koike T, Kameyama S, Takeda N, Komata T. Natural history of intracranial cavernous malformations. J Neurosurg, 1995, 83(1): 56–59. DOI:10.3171/jns.1995.83.1.0056 |

| [19] | Almefty KK, Spetzler RF. Management of brainstem cavernous malformations. World Neurosurg, 2015, 83(3): 317–319. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2014.03.019 |

| [20] | Chotai S, Qi S, Xu S. Prediction of outcomes for brainstem cavernous malformation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg, 2013, 115(10): 2117–2123. DOI:10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.07.033 |

| [21] | Sekhar LN, Mantovani A. Surgical approaches to brain stem cavernous hemangiomas. World Neurosurg, 2014, 82(6): 1028–1029. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2013.07.104 |

| [22] | Mussi AC, Rhoton AL, J r. Telovelar approach to the fourth ventricle:Microsurgical anatomy. J Neurosurg, 2000, 92(5): 812–823. DOI:10.3171/jns.2000.92.5.0812 |

| [23] | Giliberto G, Lanzino DJ, Diehn FE, Factor D, Flemming KD, Lanzino G. Brainstem cavernous malformations:Anatomical, clinical, and surgical considerations. Neurosurgical focus, 2010, 29(3): E9. DOI:10.3171/2010.6.FOCUS10133 |

| [24] | Steno J, Bizik I, Stenova J, Timarova G. Subtemporal transtentorial resection of cavernous malformations involving the pyramidal tract in the upper pons and mesencephalon. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2011, 153(10): 1955–1962. DOI:10.1007/s00701-011-1123-1 |

| [25] | Sabatino G, Rigante L, Marchese E, et al. Anterior subtemporal approach for posterolateral brainstem cavernomas:report of ten cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2012, 154(11): 2009–2016. DOI:10.1007/s00701-012-1496-9 |

| [26] | Yagmurlu K, Rhoton AL, Jr., Tanriover N, Bennett JA. Three-dimensional microsurgical anatomy and the safe entry zones of the brainstem. Neurosurgery, 2014, 10(Suppl 4): 602–619. |

| [27] | Wang CC, Liu A, Zhang JT, Sun B, Zhao YL. Surgical management of brain-stem cavernous malformations:Report of 137 cases. Surg Neurol, 2003, 59(6): 444–454. DOI:10.1016/S0090-3019(03)00187-3 |

| [28] | Mai JC, Ramanathan D, Kim LJ, Sekhar LN. Surgical resection of cavernous malformations of the brainstem:Evolution of a minimally invasive technique. World Neurosurg, 2013, 79(5-6): 691–703. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2012.04.030 |

| [29] | Abla AA, Benet A, Lawton MT. The far lateral transpontomedullary sulcus approach to pontine cavernous malformations:Technical report and surgical results. Neurosurgery, 2014, 10(Suppl 3): 472–480. |

| [30] | Yasargil MG, Reichman MV, Kubik S. Preservation of the frontotemporal branch of the facial nerve using the interfascial temporalis flap for pterional craniotomy. Technical article. J Neurosurg, 1987, 67(3): 463–466. DOI:10.3171/jns.1987.67.3.0463 |

| [31] | Hu P, Liang J, Bao Y, Li M, Ling F. The pterional transsylvian transtentorial approach to ventrolateral pontine cavernomas:Indications and techniques. World Neurosurg, 2014, 82(6): 1276–1282. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2013.06.011 |

| [32] | Asaad WF, Walcott BP, Nahed BV, Ogilvy CS. Operative management of brainstem cavernous malformations. Neurosurg Focus, 2010, 29(3): E10. DOI:10.3171/2010.6.FOCUS10134 |

| [33] | Abla AA, Spetzler RF. Minimally invasive, but not at the cost of maximally effective, in the surgical removal of brainstem cavernous malformations. World Neurosurg, 2013, 79(5-6): 638–640. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2013.01.053 |

| [34] | Linsler S, Oertel J. Endoscopic endonasal transclival resection of a brainstem cavernoma:A detailed account of our technique and comparison with the literature. World Neurosurg, 2015, 84(6): 2064–2071. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.08.029 |