Around 60 years ago,a close relative told me about a horrific accident. It took place at her friend Mrs. X's house. That was a time when people butchered chickens at home to make sure that the meat was the freshest. Mrs. X took a sharp knife and cut the chicken's neck through until the blood jetted out from a major artery. It struggled for a while and then became quiet and died. The poor dead chicken was placed in the kitchen. All along,her pet monkey was watching with enormous curiosity.

Half an hour later,her infant son fell asleep. Mrs. X left home for shopping at a nearby grocery and came back 15 minutes later. She opened the door of the room where her son's cot was located. She saw the bedclothes soaked in blood. When she took a closer look,she instantly fainted after seeing her infant baby dead. His neck was cut. She came to herself a few minutes later only to find her pet monkey sitting on the table laughing with joy,with a knife dyed with blood in its hand. There was and had been nobody else in the house.

How did the naughty monkey learn to kill? It seemed to have an accurate memory about butchering the chicken. What kind of memory was its action based upon,long-term memory,short-term memory,or working memory? Is there anything else you can learn from this incident? Please think about this incident when you read the article.

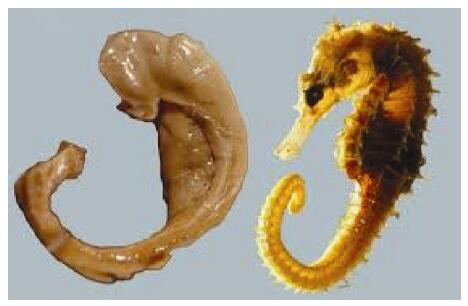

2 IntroductionThe mass readers of a journal of translational science should be clinicians instead of basic scientists. They are busy professionals and do not have much time to read about a rare topic such as the hippocampal formation (HF),which is never high on the agenda in medical education. However,it is exactly where dementia starts. From now on,the HF should and will become a very important part of medical education in the global actions against dementia. The Bolognese anatomist Giulio Cesare Aranzi was the first to coin the term "hippocampus" (Greek) in 1587 based on similarity in shape between the anatomical structure and the sea animal (Figure 1). Clinicians are not sufficiently updated with the recent advances in basic sciences about dementia. If the reading is overly challenging,they may switch off instantly. Therefore,this article is not designed to satisfy basic neuros-cientists who are armed to the teeth with all the advanced knowledge but to offer some basics to busy clinicians working on the frontline so that they can join forces to fight against dementia.

|

| Figure 1 Dissected hippocampus of human brain compared with a marine hippocampus (seahorse in Latin). It was prepared by László Seress in 1980. |

Cognitive impairment is a general term that includes anything and everything related to the mind and intelligence that are weakened or distorted. This article is focused on only one disorder: dementia. To be straightforward and honest,in many people's eyes, dementia is such a frustrating and challenging issue that a lack of interest and apathy quite often prevails. Therefore,the World Health Organization (WHO) officially labels it as a BURDEN. Denial is common. An overly serious scientific article full of difficult jargons may send most clinicians straight to snoring. The author is trying to prevent this from happening. To find the truth about dementia is like a mouse in a maze (Figure 2). Some neuroscientists have courageously invaded the maze and smelled the cheese. However,there remains some distance before they locate and eat it with joy and pleasure.

|

| Figure 2 A mouse in the maze of hippocampal formation. |

To assess the scale of the current scientific under-standing of dementia,the author has searched for books on the Amazon website using keywords "dementia","cognitive impairment",and "cognitive rehabilitation". The total is 35,625 books! The term "Alzheimer's Disease" (AD) was not used because it would have astronomically exaggerated the number of results due to duplications. It is hoped that dropping the word "Alzheimer's Disease" from the search helped avoid,to a certain extent,the massive exaggeration of the real figures. As the search was aimed at providing us with a rough idea,marginal inaccuracy is not an issue. The classified results are as follows:

• Dementia: 11,628;

• Cognitive impairment: 20,491;

• Cognitive rehabilitation: 3,506.

A search using the same keywords on PubMed located 766,691 articles since 1945. Moreover,there were 40 articles and 23 books based on the keywords of animal-assisted therapy.

If half of the staggering number of books and articles published had explained clearly the nature of the disorder and shed a bright light on how to deal with it,the problem would probably have already been resolved,and we would not have to launch the campaign of "Global Action against Dementia" after all. Unfortunately,the reality is the contrary. Clinicians do not have time to go through 6 digits of articles full of jargons they are not familiar with. Easy reading of a good and compact book to have a glance at the issue would be their preference,at least to start with. Browsing through the endlessly long list,the author has failed to locate a book with an in-depth or in- detail discussion about the root of the problem,i.e.,anatomy,physiology,and pathophysiology of the structures related to cognition and its disorder. Most of the books are empirical based on social coping. This is fully understandable because so far there is no cure for the disorder,and coping is the only option at the moment.

Alternatively,this excessive load of the literature could have crushed the community of neuroscience to death. Fortunately,this has not happened. There are warriors around who have dug and are still digging deep into the truth. The obvious example is the publication of the book entitled "Hippocampus Book"(HB) in 2007 (Figure 3)[1]. It is a milestone in the understanding of the root of dementia. One of the editors/authors is the 2014 Nobel Laureate in Physiology and Medicine,Professor John O'Keefe from the University College London. It is not an ordinary book. It is an encyclopedia of the HF. For the past three decades,the massive wealth of knowledge about the root of the problem has been accumulated although it is still far from sufficient to resolve the problem. As two of the authors of the book,Amaral and Lavenex admitted,they had only scratched the surface of the issue[2]. However,it is beyond any doubt that these heroes have largely explained how the hippocampus plays a central role in cognition and its disorders.

|

| Figure 3 The "Encyclopedia" for hippocampus. |

If practitioners are less interested and qualified to speak out about the root of the problem,neuro-scientists,both basic and clinical,should be. It is their unshirkable responsibility to advance the knowledge and translate it to the improvement of care of patients with dementia. The second part of this series of two articles aims to do that. As the population of aged patients with dementia increases sharply,relying on psychologists and psychiatrists alone is far from enough to offer a good service. It would be helpful if all relevant medical and paramedical professionals,sociologists,and social workers or even interested people without specific medical education or training could try to learn some basic knowledge of neuro-anatomy and neurophysiology related to cognition to join forces to fight against dementia. They could be relatives,friends,caregivers,or any other enthusiasts who are willing to help.

This article is not to make the readers experts on the HF. If they want to go further,they have to work on their own. A word of warning is desirable: it would be difficult for average life scientists to learn and relearn the new knowledge. Patience and perseverance required for cross-ocean swimming are indispensable for this task. Recent advances in electrophysiology and biochemistry are not discussed herein because they are too remote for clinicians. The two disciplines of mental health,psychology and psychiatry,are not discussed either unless something very crucial emerges.

3 Technological advances have galvanized basic neuroscience researchAs mentioned in Part 1 of this series of articles,cognitive disorder drew the attention of the US mili-tary first in the form of Posttraumatic Stress Syndrome followed by AD. Since then,particularly for the past 30 years,considerable achievements have been made in basic neuroscience as technologies in basic research have experienced unprecedented advances. The following are only a few of them:

(1) Molecular biology has become very advanced. There is an abundance of technologies to investigate the previously less known and sophisticated system such as the Limbic System (molecular).

(2) The traditional degeneration technique has been replaced by the new tract-tracing technique (mor-phological).

(3) The single-cell and field potential recording has been developed (in vivo electrophysiological).

(4) Acute slice recording for the demonstration of neural functions is available (in vitro morpho- physiological).

(5) The modern imaging technologies have made the invisible psychology visible and quantifiable[3]. The commonly used technologies include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI),positron emission tomography (PET),event-related potentials (ERP),and magneto-encephalography (MEG). The latter two are highly specialized technologies used by experts. Although the results of examination using these technologies may not fully correlate with the clinical manifestations of patients,important infor-mation can be collected regarding the underlying lesion and its progression (imaging).

(6) Computer models have helped to understand the complexity of the function of the HF[4].

As loss of memory is the first and most outstanding symptom of dementia,it is essential that we start from here.

4 MemoryBefore discussing memory,let us understand two technical terms of neuroscience: neural plasticity and potentiation,in simple language. Neural plasticity means a change in nerves. In living subjects,change has no other purpose than adaptation for survival. In physics,life is all about electromagnetic activities. These activities take place at the enlarged end of an axon in the form of a bulb called a synapse. The electromagnetic activity is called potentiation because electrical activity involves a difference in voltage between two points within a circuit,which in physics is known as potentiation. When a child grows,his or her knowledge and experience also grows. This is a process of learning. However,learning alone is not enough. If the child forgets what he or she has learned,the knowledge and experience never grows. The memories of what the child learns have to be stored and consolidated in the brain. These processes are known as memory. Intelligence counts on memory. Patients with dementia lose their memory and hence become less intelligent.

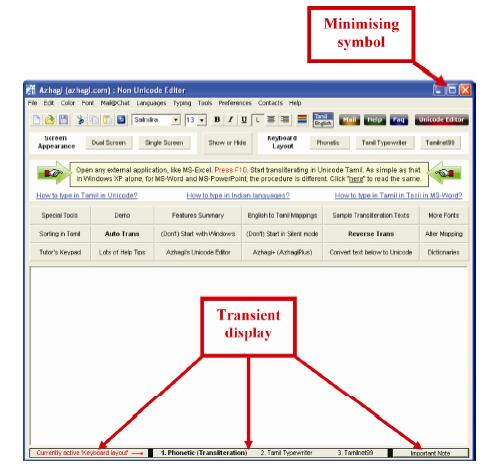

4.1 Type of memories,their creation and storageBased on the perspective of time,there are two types of memories: short-term memory (STM) and long- term memory (LTM). The processes of creating these memories are short-term potentiation (STP) and long- term potentiation (LTP) respectively[5, 6]. STP lasts for a short period,varying individually from a few seconds to minutes,and the information thus created may not be stored permanently. The metaphor of such a scenario could be creating a file on a computer without saving it; it will get lost. This is equivalent to a transient presynaptic form of plasticity. There is a special type of short memory known as the working memory[7]. It can be compared to minimizing the title of a file to the bottom of a computer screen (Figure 4). In this case,the file is not saved; however,it is on transient display. It can be brought back into action when necessary. It will be stored by pressing the save button after having created a file. It will last a long time,if not forever,and can be retrieved in the future. LTP needs sufficient time to maintain the bioelectric activities in active mode at the synapses to create proteins. This is known as LTP that lasts a few seconds to minutes or even longer. It is a process that occurs on both sides of the cell membrane at a quantum level involving ligands (ions)[8-10]. LTM through protein synthesis is retrievable. LTP can be further divided into early and late potentiation (E-LTP and L-LTP) depending upon the intensity and time of stimuli in the presence of inhibitors of protein synthes is[11]. In fact,E-LTP is not protein-dependent (protein synthesis is not required),while L-LTP is. Please note that recent memory is different from short-term memory. The distinction between short-term and long-term memories is determined by whether the memory is retrievable or not. It is an LTP if the recent memory is retrievable under normal circumstances,irrespective of the atten-tion duration paid to the words or event one has come across. People with a sharp mind can remember things in a split second. Their LTP can be very short. Apart from LTP,there is a process known as long- term depression (LTD) that indicates inhibition to counteract excitation or potentiation. In action,LTP always prevails.

|

| Figure 4 Transient display of the titles, equivalent to working memory. |

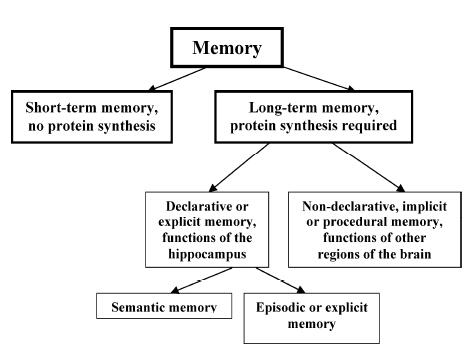

Based on the social perspective,LTMs are divided into declarative (explicit) and non-declarative ones[12] (Figure 5). The former are further divided into semantic and episodic (explicit) memories. Now,we face the barrier of unfamiliar jargons that need some simple explanations. The word "semantic" originates from the Greek word sememe that refers to a symbol. Words evolved from symbols,and hence semantic means word-related; for example,an order or declara-tion such as "Go to the toilet". In episodic memory,the mind might generate a picture of the environment,sometimes even a picture in motion in the back-ground to show the entire event dynamics from the urgency of going to the toilet and to coming out afterward. In this person's mind,everything is clearly displayed in front of him or her in the form of a picture. That is why it is also known as explicit memory. Because it is always associated with a unique environ-ment (occasion or event) or a place,it is alternatively called episodic memory.

|

| Figure 5 Taxonomy of mammalian memories. |

A single surgical operation has already provided the answer. In 1957,the American neurosurgeon William Scoville removed bilaterally the medial aspects of the temporal lobes from several patients in an attempt to relieve a variety of neurological and psychiatric con-ditions. The most exemplary of them was a patient known as H.M. He had severe epilepsy that was reduced after the removal of large part of the HF and its surrounding cortical regions bilaterally. Brenda Milner,a neuropsychologist from the McGill University,Canada was invited to assess this patient who was left with profound global amnesia[13]. This case proved that memory,the key element of cognition,is associated with the temporal lobes. Although the details of all the mechanisms remain to be identified,the HF was already known to be the factory and home of memory at that time.

5.1.1 TerminologyThe neocortex (isocortex) is closely related to cognition. In a broad sense,any cortex is new. Hence,neocortex may simply refer to any cortex[14]. However,neuros-cientists,particularly neuroanatomists use the term "neocortex" to define and describe those parts of the cortex that are interposed between various primary functional areas. They are higher-order sensory or "association" cortices also known as association areas. They include the posterior parietal cortex,prefrontal cortex,temporal association areas,insula,and areas related to language (Broca's and Wernicke's areas).

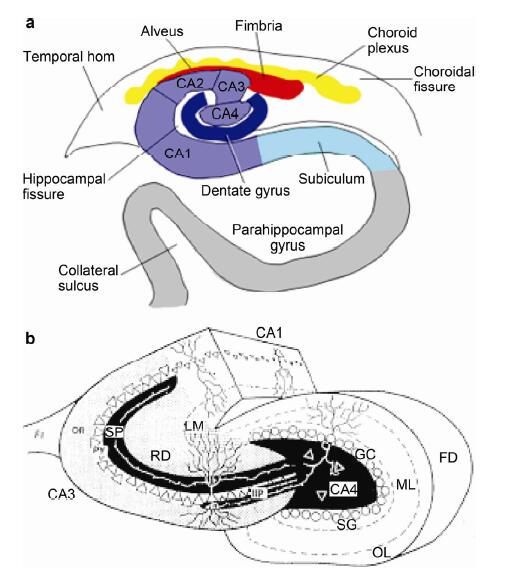

The basic structures responsible for memory are the hippocampus,entorhinal cortex,subiculum,presubiculum,parasubiculum,and dentate gyrus. Collectively,they are given the name HF. The hippocampus is further subdivided into CA1,CA2,CA3,and CA4 (Figures 6). CA stands for the Greek words Cornum Ammon,which mean horns of the Egyptian God Amun. The morphology and functions of the CA2,CA4,and the fimbria are still being investigated. It is worth noting that the fimbria is the middle part of the hippocampo-septal system that originally was thought to be very important for neural plasticity,and it still is. The history-making experiments on the system based on electron micro-scopic findings by one of the pioneers Raisman (1969) have laid the foundation for the modern understanding of neural plasticity[15-18].

|

| Figure 6 he hippocampus proper seen in a relatively horizontal direction. In a,the CA4 is wrapped in the dentate gyrus. In fact,the hippocampus is a continuous structure. Different parts are twisted and interlocked together as seen in b. Some scientists consider CA4 part of the dentate gyrus and hence it may not appear in their publications. |

The HF belongs to the LS,one of the three most ancient structures of the human central nervous system (CNS). The other two systems are the reticular for-mation and the olfactory systems. They are not only of similar age but also in close vicinity of each other[19]. Following are some of the unique features of the HF[1].

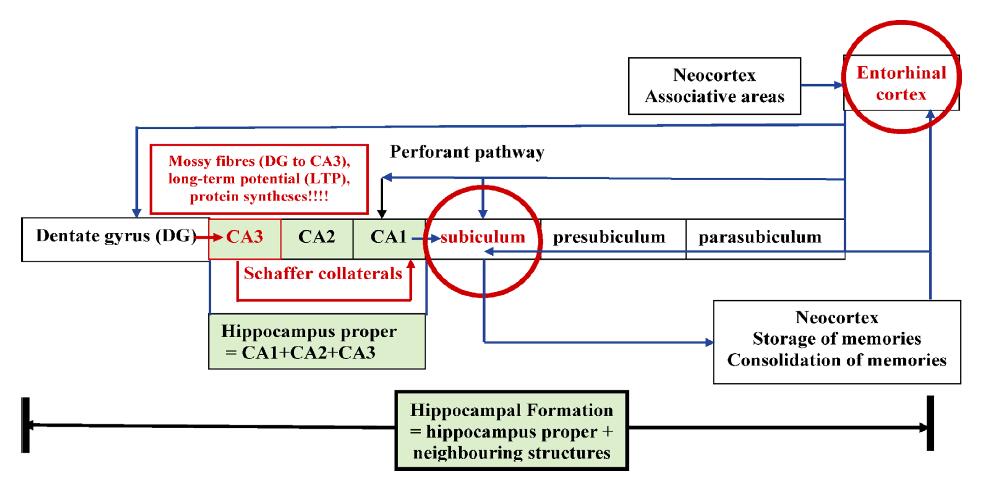

(1) Unlike other cortical projections that are reciprocal (sending a return projection),almost all projections of the HF's subdivisions are nonreciprocal and hence unidirectional. This guarantees the train of signals traveling from the entorhinal cortex to the dentate gyrus without going astray. Because this flow penetrates all subdivisions of the HF,it is named the perforant path. This specific feature might have been designed during phylogenic evolution for the specific purpose of survival instead of generalization.

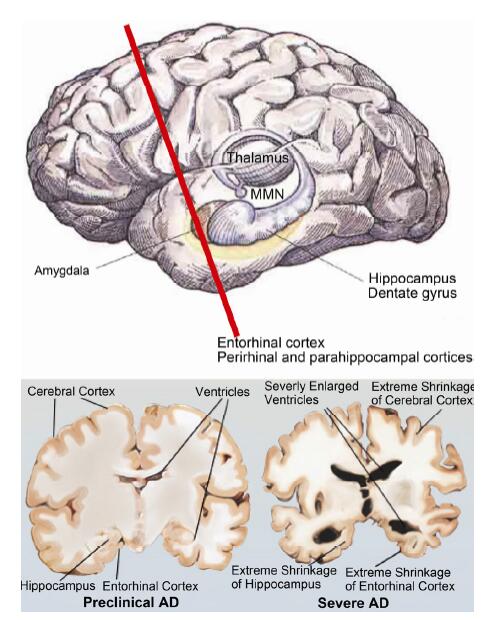

(2) The entorhinal cortex is the gateway from almost all neocortices to the entire HF. It is in here where the pathology of AD starts (Figure 7). It plays an extraordinarily important role in the flow of information through the HF.

|

| Figure 7 Cross-sections through the entorhinal cortices. The left shows mild shrinkage of the entorhinal cortices whilst the right displays severe shrinkage (courtesy of UCSF Memory and Aging Center/http://memory.ucsf.edu/education/diseases/alzheimer) (MMN: mammillary nucleus). |

(3) High-frequency stimuli of sufficient duration can initiate LTP in the mossy fibers and the Schaffer collaterals. Proteins are synthesized in the process for storage of LTM.

(4) Not all memory proteins are stored in the hippo-campus; however,spatial memory is stored there. Other types of memory use the HF as a random- access memory (RAM) to process the data,while the actual memories are stored in the hard disc (neocortex). The spatial memory is crucial for episodic memory and depends upon the existence of place cells in the hippocampus.

Figure 8 summarizes the basic information about the anatomical basis of memory. As LTP does not involve protein synthesis,transient memory is lost. LTP in the mossy fibers facilitates protein synthesis and results in the formation of LTM. The proteins are transported to the subilicum,and after exit from the hippocampus,they are transported to the neocortical regions to be stored. When necessary,they can be retrieved for use. Damage to the hippocampus alone does not wipe out these proteins in the neocortical regions. Therefore,past memories are intact and can still be retrieved. However,when another new event takes place,it is difficult,if not impossible,to create new memories because most information can no longer go through the damaged entorhinal cortex. That is why patients with dementia suffer from loss of memory about recent events while past memories survive.

Although it is dubbed as a Memory Machine,not all types of memories are created and managed by the hippocampus. The main type of memory associated with it is the spatial memory. The cell responsible for it is the place cell. A place cell is a type of pyramidal neuron within the hippocampus that becomes active when an animal enters a particular place that is known as the place field[20]. We do not live in a vacuum. Hence,the memory about any event must be associated with a place or environment. It is extremely important for memory as the first step in cognition. For this discovery,O'Keefe,May-Britt Moser,and Edvard I. Moser were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2014. The memory is probably stored in the entorhinal cortex. According to Braak and Braak,damage only to this part of the HF is classified as the transentorhinal stages I-II[21]. It is difficult at these stages to create STM. If the pathology underlying dementia extends to the entire limbic system,retrieval of the existing spatial memory is impaired. We often see patients with dementia disoriented or lost in the street. These are the limbic stages III-IV. If the lesion spreads further to most of the neocortices,the patient can become severely confused and reach the neocortex stages V-VI. Therefore,space is not just an isolated region. It is associated with all events known as declara-tive or explicit memory.

|

| Figure 8 Schematic summaries of structures of the hippocampal formation. Please note that there is only one entrance at the entorhinal cortex and one exit at the subiculum. They are both highlighted in a red circle. The proteins necessary for long-term memory are synthesized when passing through the mossy fibres. The projections jump from CA3 to CA1 via the Schaffer collaterals. |

It is known,in general,that LTM is stored in the neocortices in a distributed fashion except spatial memory[22]. So far,there is no definitive information about the details of storage. Memory has to be con-solidated. Otherwise,it will fade away quickly with time. The exact mechanisms of consolidation are still being investigated. As mentioned above,if the pathology extends beyond the hippocampus to the neocortices,the storage of memories may also be destroyed,and past memories will suffer.

5.1.4 Changing boundaries of the LSTraditionally,LS is comprised of a series of con-tiguous cortical and subcortical structures located on the medial surface of the brain and surrounding the ventricles along its border of the cortical mantle. The word "limbic" means border in Latin (limbus). It stems from the description by Broca (1878) "le grande lobe limbique"[2]. It is thought to be responsible for cognition (including memory) and emotion. Anderson et al. suggest that the HF is independent from the LS due to its unique contribution to memory and cognition[1]. However,they stop short of abandoning the term LS completely. The close connections among structures such as the amygdala,hypothalamus,and periaqueductal gray,suggest that the HF does not act alone in cognition without the involvement of other systems like the amygdala,autonomic organs,and endocrine glands[22, 23]. It seems that cognition must be affected by or affect emotion.

New discoveries indicate that the boundaries of the LS-specific for cognition are not well-defined[24]. In 1987,the nucleus basalis of Meynert outside the LS was found to be severely damaged in dementia[25, 26]. The interest in the septohippocampal system persists,and it remains under investigation. Even more recently,it was discovered that the cerebellum,normally a motor controller,has cognitive function[27]. However,it is understood that the cerebellum is involved in developing dexterity that requires repeated adjustment of movements in the learning process. Sciences are evolving fast,and we must keep pace with its rhythm.

6 Symptomatology and diagnosis of dementiaThis section is not aimed at describing the sympto-matology and diagnosis of dementia in detail. It is to point out that over-diagnosis is better than under- diagnosis because the latter may cause the patient and all involved to slacken their vigilance,and appropriate interventions may be delayed. Decline in cognitive function (cognitive impairment) is associated with aging. The questions are "what is normal (benign) aging?" and "what is premature (malignant) decline?" It is difficult in marginal cases to make the exact distinction. Therefore,a special,universally accepted term is created,called Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)[28, 29]. It is like sitting on the fence overseeing both sides so that nothing would be missed. This may also be important for legal reasons to indicate that the physician has not missed anything. More importantly,this cautious attitude can raise early suspicion and detection leading to early diagnosis and interventions.

7 What can we do innovatively to tackle dementia?The existing medications for dementia on the market are far from satisfactory. Neither the US nor the UK health authorities widely recommend them because of the uncertainty of the effect and the high cost/effect ratio. Readers can find such information easily on the internet. That is why WHO calls for developing innovative methods. Herein,we discuss four aspects of the issue: insulin-like growth factor (IGFs),brain stimulations,cell transplantation,and animal-assisted therapy.

7.1 Can insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) contribute to the modulation or repair of the hippocampus?We know that insulin regulates glucose metabolism. In 1967,insulin was found in the cerebrospinal fluid[30]. Later,it was connected to a hippocampal lesion and AD[3]. There are a group of hormones with high sequence similarity to insulin; however,their functions are somewhat different. In the beginning,scientists mixed insulin secreted by β cells of the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas with the nerve growth factor. This newly discovered hormone has another function of stimulating growth. Combining this similarity and difference,early scientists gave them the name insulin-like growth factors (IGFs). It was previously called somatomedin. The word "somato" means body while "medin" means origin. What "medin" means herein is not clear. Two types of IGF (IGF-1 and -2) are most important. The former is produced in the pancreas while the latter in the liver and other tissues. IGF was discovered as early as 1976 to have an impact on the hippocampus[31]. Since the beginning of the 21st century,the interest in this hor-mone of the neuroscience c ommunity has soared[32-49]. The key question of the role of insulin or insulin-like substance on the hippocampus is how the blood- brain-barrier (BBB) allows the large molecules of a complete protein to pass through. Normally,BBB only allows glucose and amino acids to permeate. Hence,some scientists assumed that there had to be a similar hormone produced inside the brain[47-49]. However,most scientists believe that IGFs are secreted from the pancreas and liver under the stimulation by the growth hormone. IGF-1 is produced during pregnancy,while secretion of IGF-2 carries on during adult life. Scientists still debate how they could pass through the BBB,or if they are produced in the brain.

On top of the BBB,there is the blood-brain-CSF barrier. That they combined is not a tight molecular system. The capillary endothelium in the choroid plexus and other places in the ventricles is fenestrated and can let the substances from the blood pass through. These exceptional regions are called circumventricular organs[50]. Some large molecules can pass through probably by chance via these small windows. Others suggest that the permeability of the BBB is also dependent upon neuron receptors that regulate the opening of the window[36-38, 42]. There are reports that insulin could pass along the olfactory nerve into the brain via the intranasal delivery of insulin[39, 43]. A report even suggests a transanal route of delivery[40]. Furthermore,the BBB can be faulty under pathological situations,and it depends upon insulin-receptor to allow IGF to pass through. Whatever its source,the evidence of insulin in the CSF after peripheral delivery confirms that there are IGFs in the brain[51]. This would have important positive implications for its potential use for neurogenesis whether as an independent agent or a supplement in tackling dementia.

7.2 Brain stimulationThe types of brain stimulation are:

(1) Noninvasive

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS);

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

(2) Invasive

Deep brain stimulation (DBS).

In rTMS,repetition is to enhance the effect by changing polarity regularly. This is similar to the electric stimulation of a muscle in which only alternative current works. DBS requires an operation to implant the parts of the devices into the body. All these electric procedures are high expertise job of electrical engineering. Brain stimulation has been approved by Food and Drug Administration for Parkinson's Disease,other motor disorders,and depression. They are in the phase of tentative clinical trial or early phase of therapy. The technology is yet to be approved by FDA for dementia. Only two articles report the use of these methods of brain stimulation for dementia[52, 53]. Properly organized studies on brain stimulations for dementia are yet to be conducted. These methods claim moderate benefit to this devastating disorder,and there are some problems that need to be addressed.

The most unpleasant and unsafe side effect is the occurrence of seizures,although it is rare but very worrying. This is almost unavoidable in theory because the area of the firing neurons for seizures is located in the vicinity of or within the HF itself[54]. These neurons have a lower threshold of firing than others do. Another unpleasant feature of TMS and rTMS is not a side effect but annoying or even unbearable for many. It is the high pitch loud noise from generating the magnetic field. Some patients even refuse to carry on for this simple and single reason. Another pro-blem common to the methods is the repetition of the therapeutic session that normally takes 40 minutes each,5 days a week for 4-6 weeks. Therefore,it is still a cumbersome method needing close monitoring. Whether these results are acceptable for trial for a devastating condition due to the lack of a better alternative,remains to be seen.

7.3 Cell transplantationOlfactory ensheathing cell transplantation (OECT) has been successful in some conditions; however,many works with less than satisfactory reorganization are not universally recognized[55-57]. Despite this hurdle,cell therapy seems to be unstoppable. So far,this method has not been approved worldwide or by FDA for dementia. High-quality animal experiments and tentative clinical studies are necessary to set a standard for its translation to bedside.

There are a number of theoretical reasons to support this initiative. Anderson and his group in a series of studies in rats have convincingly proven that hippocampal synapses are highly plastic[4]. These studies have laid a solid foundation,among other things for cell transplantation based on plasticity. Hippocampal neurons are transplantable with retention of many basic properties. Probably there is nothing more encouraging than this skill for animal survival. However,Raisman warned that the reor-ganization was not necessarily adaptive or functionally important. This may be an underestimation of its po-tential. Furthermore,vigorous animal experiments and human clinical trials may deliver a more optimistic outcome.

Hippocampal cells also grow well in culture with both neurons and glia readily identifiable and may be manipulated[4]. This is extremely important in avoiding the risk that stem cells can go astray during mutation. However,with time in culture,the original cytoar-chitecture disappears,suggesting a loss of function. More preclinical experiments are needed to resolve this problem,and using other highly potential cells of any of the most ancient parts of the human CNS is an alternative.

In both brain stimulation and cell transplantation,the interventions directly affect the brain. It might be reasonable to compare the advantages and disad-vantages of cell transplantation. It could be useful in selecting the right project. Many institutions and individuals are reluctant to embark on this most challenging mission. For this reason,let us discuss its disadvantages first to understand why people's attitudes are so cautious.

7.3.1 AdvantagesWith meticulous preparation and successful outcome,it may have the following advantages.

(1) No adverse effects have been reported in cell transplantation into the human CNS with pre-cursor cells or more mature cells. It seems that the procedure is safe as Phase One of a clinical trial. The next target is Phase Two (efficacy).

(2) The three most ancient systems of the human CNS,the reticular formation,limbic system,and olfactory system,retain the ability to regenerate or to stimulate regeneration although more evidence is needed to substantiate the claim further[2-3, 17].

(3) Living cells are nanomachines. Transplanted cells are no exception. They possess the capability of self-assembly and self-repair through adaptation to the new environment. Their biocompatibility must be high[10]. Once the operation is uneventful,there is no need for frequent interventions as in brain stimulation. The author saw an incidental patient from the US 10 years ago with motor neuron disease who had received OECT into the corona radiata. She was operated upon by Dr. Hongyun Huang,the Chinese neurosurgeon who was first in the world to perform OECT in humans[54]. The author saw her around 6 months after the OECT. She told the author that the original positive results were fading. She wanted to have another transplantation. The author questioned the rationale of doing so; however,the patient insisted it is the correct decision for her because the quality of life had improved after the first OECT. However,Dr. Huang declined another attempt. He was concerned that it would be too many repetitive operations during her lifetime,and the positive results might decline. It is possible that the clinical trials for dementia may offer a better outcome for a system phylogenetically more ancient than the motor- related corona radiata.

7.3.2 Disadvantages(1) Only an institution with advanced expertise in neuroscience and neurosurgery can be qualified to take on the mission.

(2) It needs special approval.

(3) It may have adverse effects including mutation into malignancy. That is why now scientists use precursors that will only grow into nerve tissues.

(4) It is a method that needs long hi-tech preparation from harvesting cells to culture and from animal experiment to operating theater.

(5) It is associated with risks of any neurosurgical operation.

(6) It requires a relatively long in-hospital stay.

(7) It is an expensive procedure,the benefits of which may not last forever.

7.4 Animal-assisted therapyAnimal-assisted therapy (AAT) is an ancient idea as the human-animal bond is a normal part of animal evolution[58]. In this article,we discuss the problems of the modern time. Animals can be used for the treatment of physical disorders; however,herein we discuss cognition disorders only. An animal can help improve or stabilize the mood of the person concerned,and as a result,the entire mental status. In modern medicine,the founder of Rehabilitation Medicine Dr. Howard Rusk observed depression of an injured young United States soldier during his physical rehabilitation[59]. He did not talk to anybody; however,after a woman offered him a dog,he became happier and began to speak,and the rehab team realized his wife wanted to divorce him.

It has to be emphasized that cognition rehabilitation is not only a science but also an art. Concrete measures have to be tailored to suit the individual's conditions based on some general principles. Innovative thinking is essential. A United Kingdom Royal Navy officer suffered from a severe head injury in the Persian Gulf War in 1990 and lost 50% of his memories. He did not even recognize his wife and longtime neighbors. He later picked up his memory after 5 years' living in com-pany with a dog,the man's best friend. The dog was known as Endal,the world's most decorated dog who passed away[60]. This case is different from dementia where loss of recent memory and damage to the entorhinal cortex are the primary focus. This is a case of widespread traumatic brain injury that affects all sections of the brain including the primary cortex,neocortex,and LS. His memory recovery must have covered all these regions instead of the deep-lying medial temporal lobe alone. There is no reason to believe why this method cannot be used successfully for dementia where the early phase of pathology is restricted to the entorhinal cortex and hence much less severe than the officer's brain damage.

This case suggests that high frequency of inter-actions may have played an important role in the success. No human can look after a patient with such high frequency like a dog. This case is also very encouraging in the sense that if an unresponsive patient can regain responses after many years,the outcome of cognitive rehabilitation may not seem as negative as it appears. With perseverance and creativeness,a better outcome may be achieved. This animal-assisted therapy has been extended to toy animals. With the ever-growing size of the aging po-pulation,shortage of human resources is inevitable. Borrowing a hand from a pet,a working animal or even a toy animal could be helpful.

It deserves special attention that since the end of the last century,an overwhelming number of publications on AAT have universally reported its success. This success does not necessarily mean cure. However,in almost all reports alleviation of symptoms is observed,or the disease is stabilized compared with the control[58, 60-81]. This high rate of success has made AAT stand out from the other three methods mentioned above. It is also based on a long-existent traditional and universal animal-human bond that does not need special and cumbersome application and approval involving health authorities. As the current level of neuroscience stands,this method seems to be the method of choice if available and socially appropriate. Regretfully,so far,neuroscientists are yet to be involved although they are the experts that the patients with dementia and their caregivers trust the most. There could be a misunderstanding that animal-assisted therapy is low-tech that high-profile neuroscientists should not be involved due to the risk lowering their academic status. Tackling dementia is of utmost importance to the society. Neuroscientists must also fulfill their social responsibility to join forces with other professionals. It is hoped that neuroscientists, both basic and clinical,will take on the mission sooner rather than later. There is much of high-profile science that needs to be performed in AAT,particularly in terms of psychology and psychiatry of humans and animals in their interactions.

It is obvious that of all animals,the dog is the first choice being man's best friend for tens of thousand of years. The next question is "which breed is the best for the purpose of companionship?" The Encyclopedia of Dog Breeds describes Labrador as "good tempered,very agile,an adaptable and devoted companion who is intelligent,keen,and biddable,with a very strong will to please[82]." There cannot be a better candidate for this purpose!

Nothing can happen from nowhere. Governments of all countries should encourage and support scientists to innovate new methods of treatment of dementia. Fast track approval similar to that for Ebola virus infection may be necessary for innovative inter-ventions against dementia as well. Although dementia itself is a slow-progressing disease,the scale of its increase is an epidemic. Financial institutions should have the initiatives to invest in this most important humanitarian endeavor. The broken planet needs a new Marshall Aid Plan to save its residents!

Let us innovate!

| [1] | Anderson P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O'Keefe J, eds and auths. The Hippocampus Book. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007 . |

| [2] | Amaral D, Lavenex P. Chapter 3 Hippocampal neuroanatomy. In Anderson P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O'Keefe J. The Hippocampus Book. Anderson P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O'Keefe J, Eds. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007 : 37 -114. |

| [3] | Stuss DT. Introduction to section 2. In Cognitive Neurorehabilitation. Stuss DT, Wincocur G, Robertson IH, Eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008 : 121 -123. |

| [4] | Anderson P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O'Keefe J. Historical perspective: proposed functions, biological characteristics, and neurobilogical models of the hippocampus. In Anderson P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O'Keefe J. The Hippocampus Book. Anderson P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O'Keefe J, Eds. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007 : 9 -36. |

| [5] | Volinanski A, Jensen MS. Transient and sustained types of long-term potentiation in the CA1 area of the rat hippocampus. J Physiol (London) , 2003, 550 (Pt 2) : 459–492. |

| [6] | Bliss TVP, Lomo T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetizsed rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol , 1973, 232 (2) : 331–356. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273 |

| [7] | Baddeley AD. Working memory. Science , 1992, 255 (5044) : 556–559. DOI:10.1126/science.1736359 |

| [8] | Bliss T, Collingridge G, Morris R. Chapter 10 Synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. In The Hippocampus Book. Anderson P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O'Keefe J, Eds. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007 : 343 -474. |

| [9] | Levitan IB, Kaczmarek LK. Chapter 9 Synaptic release of neurotransmitters. In Section IV: Behavior and plasticity, The Neuron: Cell and Molecular Biology. 3rd edn. Levitan IB, Kaczmarek LK, Eds. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002 : 195 -221. |

| [10] | Jones RAL. Wetware: chemical computing from bacteria to brain. In Soft Machines: Nanotechnology and Life. Jones RAL, Ed. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004 6(reprint) : 168 -185. |

| [11] | Frey U, Huang YY, Kandel ER. Effects of cAMP simulate a late stage of LTP in hippocampal CA1! neurons. Science , 1993, 260 (5114) : 1661–1664. DOI:10.1126/science.8389057 |

| [12] | Cohen NJ, Squire LR. Preserved learning and retention of pattern-analyszing skill in amnesia: dissociation of knowing how and knowing that. Science , 1980, 210 (4466) : 207–210. DOI:10.1126/science.7414331 |

| [13] | Scoville WB, Milner B. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry , 1957, 20 (1) : 11–21. DOI:10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11 |

| [14] | Striedter GF. Principles of Brain Evolution, Sinasaur Associates. Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 2005, p 436. |

| [15] | Raisman G, Cowan WM, Powell TPS. The extrinsic afferent, commissural and association fibres of the hippocampus. Brain , 1965, 88 (5) : 963–998. DOI:10.1093/brain/88.5.963 |

| [16] | Raisman G, Cowan WM, Powell TPS. An experimental analysis of the efferent projection of the hippocampus. Brain , 1966, 89 (1) : 83–108. DOI:10.1093/brain/89.1.83 |

| [17] | Raisman G. Neuronal plasticity in the septal nuclei of the adult rat. Brain Res , 1969, 14 (1) : 25–48. DOI:10.1016/0006-8993(69)90029-8 |

| [18] | Raisman G, Field PM. A quantitative investigation of the development of collateral reinnervation after partial dieafferentiation of the sepatial nuclei. Neuronal plasticity in the septal nuclei of the adult rat. Brain Res , 1973, 50 (2) : 241–264. DOI:10.1016/0006-8993(73)90729-4 |

| [19] | Patestas MA, Gartner LP. Chapter 14 Reticular formation. In A Textbook of Neuroanatomy. Patestas MA, Gartdner LP, Eds. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006, pp 241-252. |

| [20] | O'Keefe J, Dostrovsky J. The hippocampus as a spatial map: pPreliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Res , 1971, 34 (1) : 171–175. DOI:10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1 |

| [21] | Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuro-pathol (Berl) , 1991, 82 (4) : 239–259. DOI:10.1007/BF00308809 |

| [22] | Brodal P. Chapter 32 The hippocampal formation: learning and memory. In: The Central Nervous System: Structure and Function, 4th ed. Brodal P, Ed. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010 : 473 -482. |

| [23] | Damasio AR. Toward a neurobiology of emotion and feeling: operational concepts and hypotheses. Neuroscientist , 1995, 1 (1) : 19–25. DOI:10.1177/107385849500100104 |

| [24] | Brodal P. Chapter 32 The amygdale, the basal forebrain, and emotions. In The Central Nervous System-: Structure and Function, 4th ed. Brodal P, Ed. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press,, 2010 : 461 -471. |

| [25] | Arendt T, Bigl V, Arendt A, Tennstedt A. Loss of neurons in the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer's disease, paralysis agitans and Korsakoff's Disease. Acta Neuropathol , 1983, 61 (2) : 101–108. DOI:10.1007/BF00697388 |

| [26] | Brodal P. Chapter 32 The cerebellum In The Central Nervous System: Structure and Function, 4th ed., Brodal P, Eds. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010 : 343 -361. |

| [27] | Flicker CS, Ferris SH, Reisberg B. Mild cognitive impairment in the elderly: predictors of dementia. Neurology , 1991, 41 (7) : 1006–1009. DOI:10.1212/WNL.41.7.1006 |

| [28] | Smith GE, Bondi MW. Chapter 3 Normal cognitive aging. In Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Definitions, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Smith GE, Bondi MW eds and auths, Eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013 : 37 -68. |

| [29] | Margolis RU, Altszuler N. Insulin in the cerebrospinal fluid. Nature , 1967, 215 (5108) : 1375–1376. DOI:10.1038/2151375a0 |

| [30] | De Castro JM, Balagura S. Insulin pretreatment facilitates recovery after dorsal hippocampal lesions. Physiol Behav , 1976, 16 (5) : 517–520. DOI:10.1016/0031-9384(76)90208-0 |

| [31] | Fröolich L, Blum-Degen D, Bernstein HG, Engelsberger S, Humrich J, Laufer S, Muschner D, Thalheimer A, Türk A, Hoyer S, Zöchling R, Boissl KW, Jellinger K, Riederer P. Brain insulin and insulin receptors in aging and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm , 1998, 105 (4-5) : 423–438. |

| [32] | Gaspar JM, Baptista FI, Macedo MP, Ambrósio AF. Inside the diabetic brain: role of different players involved in cognitive decline. ACS Chem Neurosci 2016. ACS Chem Neurosci , 2016, 7 (2) : 131–142. DOI:10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00240 |

| [33] | McGinley LM, Sims E, Lunn JS, Kashlan ON, Chen KS, Bruno ES, Pacut CM, Hazel T, Johe K, Sakowski SA, Feldman EL. Human cortical neural stem cells expressing insulin-like growth factor-I: A novel cellular therapy for Alzheimer's disease. Stem Cells Transl Med , 2016, 5 (3) : 379–391. DOI:10.5966/sctm.2015-0103 |

| [34] | Kimoto A, Kasanuki K, Kumagai R, Shibata N, Ichimiya Y, Arai H. Serum insulin-like growth factor-I and amyloid beta protein in Alzheimer's disease: relationship with cognitive function. Psychogeriatrics , 2016, 16 (4) : 247–254. DOI:10.1111/psyg.2016.16.issue-4 |

| [35] | Willette AA, Bendlin BB, Starks EJ, Birdsill AC, Johnson SC, Christian BT, Okonkwo OC, La Rue A, Hermann BP, Koscik RL, Jonaitis EM, Sager MA, Asthana S. Association of insulin resistance with cerebral glucose uptake in late middle-aged adults at risk for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol , 2015, 72 (9) : 1013–1020. DOI:10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0613 |

| [36] | Grünblatt E, Bartl J, Iuhos DI, Knezovic A, Trkulja V, Riederer P, Walitza S, Salkovic-Petrisic M. Characterization of cognitive deficits in spontaneously hypertensive rats, accompanied by brain insulin receptor dysfunction. J Mol Psychiatry , 2015, 3 (1) : 6. DOI:10.1186/s40303-015-0012-6 |

| [37] | Freude S, Schilbach K, Schubert M. The role of IGF-1 receptor and insulin receptor signaling for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: from model organisms to human disease. Curr Alzheimer Res , 2009, 6 (3) : 213–223. DOI:10.2174/156720509788486527 |

| [38] | Boado RJ, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Xia CF, Pardridge WM. Fusion antibody for Alzheimer's disease with bidirectional transport across the blood-brain barrier and abeta fibril disaggregation. Bioconjug Chem , 2007, 18 (2) : 447–455. DOI:10.1021/bc060349x |

| [39] | Benedict C, Frey WH Ⅱ, Schiöth HB, Schultes B, Born J, Hallschmid M. Intranasal insulin as a therapeutic option in the treatment of cognitive impairments. Exp Gerontol , 2011, 46 (2-3) : 112–115. DOI:10.1016/j.exger.2010.08.026 |

| [40] | Zhang T, Qu H, Li X, Zhao B, Zhou J, Li Q, Sun MJ. Transmembrane delivery and biological effect of human growth hormone via a phage displayed peptide in vivo and in vitro. J Pharm Sci , 2010, 99 (12) : 4880–4891. DOI:10.1002/jps.22203 |

| [41] | Lupien SB, Bluhm EJ, Ishii DN. Systemic insulin-like growth factor-I administration prevents cognitive impairment in diabetic rats, and brain IGF regulates learning/memory in normal adult rats. J Neurosci Res , 2003, 74 (4) : 512–523. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-4547 |

| [42] | Messier C, Teutenberg K. The role of insulin, insulin growth factor, and insulin-degrading enzyme in brain aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neural Plast , 2005, 12 (4) : 311–328. DOI:10.1155/NP.2005.311 |

| [43] | Hanson LR, Frey WH. Strategies for intranasal delivery of therapeutics for the prevention and treatment of neuroAIDS. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol , 2007, 2 (1) : 81–86. DOI:10.1007/s11481-006-9039-x |

| [44] | Recio-Pinto E, Rechler MM, Ishii DN. Effects of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-Ⅱ, and nerve growth factor on neurite formation and survival in cultured sympathetic and sensory neurons. J Neurosci , 1986, 6 (5) : 1211–1219. |

| [45] | Talbot K, Wang HY. The nature, significance, and glucagon-like peptide-1 analog treatment of brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement , 2014, 10 (S1) : S12–S25. |

| [46] | Duarte AI, Candeias E, Correia SC, Santos RX, Carvalho C, Cardoso S, Plácido A, Santos MS, Oliveira CR, Moreira PI. Crosstalk between diabetes and brain: Glucagon-like peptide-1 mimetics as a promising therapy against neuro-degeneration. BBA-Mol Basis Dis , 2013, 1382 (4) : 527–541. |

| [47] | de la Monte SM. Triangulated mal-signaling in Alzheimer's disease: Roles of neurotoxic ceramides, ER stress, and insulin resistance reviewed. J Alzheimers Dis , 2012, 30 : S231–S249. |

| [48] | de la Monte SM., Wands JR. Alzheimer's disease is type 3 diabetes-evidence reviewed. J Diabetes Sci Technol , 2008, 2 (6) : 1101–1113. DOI:10.1177/193229680800200619 |

| [49] | Zemva J, Schubert M. The role of neuronal insulin/ insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: possible therapeutic implications. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets , 2014, 13 (2) : 322–337. DOI:10.2174/18715273113126660141 |

| [50] | Brodal P. Chapter 8 The blood supply of the CNS. In The Central Nervous System: Structure and Function, 4th ed. Brodal P, Ed. Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press,, 2010 : 104 -113. |

| [51] | Plata-Salamán CR. Insulin in the cerebrospinal fluid. Neurosci Biobehav Rev , 1991, 15 (2) : 243–258. DOI:10.1016/S0149-7634(05)80004-1 |

| [52] | Nardone R, Höller Y, Tezzon F, Christova M, Schwenker K, Golaszewski S, Trinka E, Brigo F. Neurostimulation in Alzheimer's disease: from basic research to clinical applications. Neurol Sci , 2015, 36 (5) : 689–700. DOI:10.1007/s10072-015-2120-6 |

| [53] | Kuhn J, Hardenacke K, Lenartz D, Gruendler T, Ullsperger M, Bartsch C, Mai JK, Zilles K, Bauer A, Matusch A, Schulz RJ, Noreik M, Bührle CP, Maintz D, Woopen C, Häussermann P, Hellmich M, Klosterkötter J, Wiltfang J, Maarouf M, Freund HJ, Sturm V. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer's dementia. Mol Psychiatry , 2015, 20 (3) : 353–360. DOI:10.1038/mp.2014.32 |

| [54] | Avoli M. The epileptic hippocampus revisited: Back to the future. Epilepsy Curr , 2007, 7 (4) : 116–118. DOI:10.1111/epc.2007.7.issue-4 |

| [55] | Guest J, Herrera LP, Qian T. Rapid recovery of segmental neurological function in a tetraplegic patient following transplantation of fetal olfactory bulb-derived cells. Spinal Cord , 2006, 44 (3) : 135–142. DOI:10.1038/sj.sc.3101820 |

| [56] | Huang HY, Wang HM, Xiu B, Wang R, Lu M, Chen L, Qi S B, Chen L, Zhang ZH, Wu HQ. Preliminary report on the results of clinical trial of for olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation in the treatmenting of the spinal cord injury. J Naval Gen Hosp , 2002, 15 (1) : 18–21. |

| [57] | Tabakow P, Jarmundowicz W, Czapiga B, Fortuna W, Miedzybrodzki R, Czyz M, Huber J, Szarek D, Okurowski S, Szewczyk P, Gorski A, Raisman G. Transplantation of autologous olfactory ensheathing cells in complete human spinal cord injury. Cell Transplant , 2013, 22 (9) : 1591–612. DOI:10.3727/096368912X663532 |

| [58] | Fine AH, Beck AM. Understanding our kinship with animals: input for health care professionals interested in the human-animal bond. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy. 4th edn. Fine AH, Beck AM, Eds. Amsterdam, Boston: Elsevier, 2015, pp 3-10. |

| [59] | Rusk H. Chapter IV. In A World to Care for: The autobiography of Howard A. Rusk MD, Rusk HA, Eds. New York: Random House, 1972, pp 55-80. |

| [60] | Parton A, Parton SE: How One Extraordinary Dog Brought a Family Back from the Brink. London: Harper, 2009. |

| [61] | Orlandi M, Trangeled K, Mambrini A, Tagliani M, Ferrarini A, Zanetti L, Tartarini R, Pacetti P, Cantore M. Pet therapy effects on oncological day hospital patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Anticancer Res , 2007, 27 (6C) : 4301–4307. |

| [62] | Brickel CM. Depression in the nursing home: A pilot study using pet-facilitated psychotherapy. Center to study Human-Animal Relationships and Environments, Minnesota, USA, 1984, pp 407-415. |

| [63] | Jessen J, Cardiello F, Baun MM. Avian companionship in alleviation of depression, loneliness, and low morale of older patients adults in skilled rehabilitation units. Psychological Rep , 1996, 78 (1) : 339–348. DOI:10.2466/pr0.1996.78.1.339 |

| [64] | Lutwak-Bloom P, Wijewickrama R, Smith B. Effects of pets versus people visits with nursing home residents. J Gerontol Soc Work , 2005, 44 (3-/4) : 137–159. |

| [65] | Bank MR, Banks WA. The effects of animal-assisted therapy on loneliness in an elderly population in long-term care facilities. Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sciogy , 2005, 57 (7) : M428–M432. |

| [66] | Churchill M, Safaoui J, McCabe BW, Baun MM. Using a therapy dog to alleviate the agitation and desocialization of people with Alzheimer's disease. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv , 1999, 37 (4) : 16–22. |

| [67] | Richeson NE. Effects of animal-assisted therapy on agitated behaviors and social interactions of older adults with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen , 2003, 18 (6) : 353–358. DOI:10.1177/153331750301800610 |

| [68] | Fritz CL, Farver TB, Kass PH, Hart LA. Association with companion animals and the expression of noncognitive symptoms in Alzheimer's patients. J Nerv Ment Dis , 1995, 183 (7) : 459–463. DOI:10.1097/00005053-199507000-00006 |

| [69] | Fick KM. The influence of an animal on social interactions of nursing home residents in a group setting. American J Occup Ther , 1993, 47 (6) : 529–534. DOI:10.5014/ajot.47.6.529 |

| [70] | Kongable LG, Buckwalter KC, Stolley JM. The effects of pet therapy on the social behavior of institutionalized Alzheimer's clients. Arch Psy Nursing , 1989, 3 (4) : 191–198. |

| [71] | Majić T, Gutzmann H, Heinz A, Lang UE, Rapp MA. Animal-assisted therapy and agitation and depression in nursing home residents with dementia: a matched case-control trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry , 2013, 21 (11) : 1052–1059. DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.03.004 |

| [72] | Mossello E, Ridolfi A, Mello AM, Lorenzini G, Mugnai F, Piccini C, Barone D, Peruzzi A, Masotti G, Marchionni N. Animal-assisted activity and emotional status of patients with Alzheimer's disease in day care. Int Psychogeriatr , 2011, 23 (6) : 899–905. DOI:10.1017/S1041610211000226 |

| [73] | Banks MR, Willoughby LM, Banks WA. Animal-assisted therapy and loneliness in nursing homes: use of robotic versus living dogs. J Am Med Dir Assoc , 2008, 9 (3) : 173–177. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2007.11.007 |

| [74] | Edwards NE, Beck AM. Animal-assisted therapy and nutrition in Alzheimer's disease. West J Nurs Res , 2002, 24 (6) : 697–712. DOI:10.1177/019394502320555430 |

| [75] | Ruckdeschel K, Van Haitasma K. The impact of live-in animals and plants on nursing home residents: a pilot longitudinal investigation. Alzheimers Care Q , 2001, 2 (4) : 17–27. |

| [76] | Bank MR, Banks WA. The effects of group and individual animal-assisted therapy on loneliness in residents of long-term care facilities. Anthrozoös , 2005, 18 (4) : 396–408. DOI:10.2752/089279305785593983 |

| [77] | Le Roux MC, Kemp R. Effect of a companion dog on depression and anxiety levels of elderly residents in a long-term care facility. Psychogeriatrics , 2009, 9 (1) : 23–26. DOI:10.1111/psy.2009.9.issue-1 |

| [78] | Friedmann E, Galik E, Thomas SA, Hall PS, Chung SY, McCune S. Evaluation of a pet-assisted living intervention for improving functional status in assisted living residents with mild to moderate cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen , 2014, 5,130 (13) : 1276–14289. |

| [79] | Bernstein PL, Friedmann E, Malaspina A. Animal-assisted therapy enhances resident social action interaction and initiation in long-term care facilities. Anthrozoös , 2000, 13 (4) : 213–224. DOI:10.2752/089279300786999743 |

| [80] | Crowley-Robinson P, Blackshaw JK. Nursing home staffs' empathy for a missing therapy dog, their attitudes to animal-assisted therapy programs and suitable dog breeds. Anthrozoös , 1998, 11 (2) : 101–104. DOI:10.2752/089279398787000779 |

| [81] | Kaiser L, Spence LJ, McGavin L, Struble L, Keilman L. A dog and a "happy person" visit nursing home residents. West J Nurs Res , 2002, 24 (6) : 671–683. DOI:10.1177/019394502320555412 |

| [82] | Cunliffe J. The Encyclopedia of Dog Breeds. Bath: Paragon, 2002. |