Primary trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is characterized by episodic, paroxysmal, and trigger-pain, which can be alleviated through the use of carbamazepine. Trigeminal neuralgia severely compromises the oral hygiene, face-washing abilities, mastication, and quality of life of patients; thus, patients often become depressed. There are 155 habitants out of every 1, 000, 000 that are affected by TN[1]. This retrospective study divided 109 TN cases into 3 groups according to the different microsurgical manners used. The objective of this study was to summarize the surgical outcomes and complications of the microsurgical methods for TN.

2 Methods 2.1 Clinical dataWe retrospectively reviewed 109 TN cases, with 48 males and 61 females, who had retrosigmoid cranial nerve surgery performed for treatment of TN without tumors. Patients’ ages ranged from 26 to 79 years old (mean 55.5±13.0 years), and the duration of TN ranged from 0.2 to 29 years (mean 8.5±6.6 years). All patients had classical TN without sustained pain, according to criteria from the International Headache Society. The TN was right-sided in 73 patients and left-sided in 36 patients. The distribution of TN was V1+2 in 3 patients, V1+2+3 in 4 patients, V2+3 in 32 patients, V2 in 40 patients, and V3 in 30 patients. Operative findings showed no vascular compression in 9 patients (8.3%), vascular compression in 100 patients (91.7%), arterial compressions in 77 patients (70.6%), venous compressions in 8 patients (7.3%), and arterial and venous compressions in 15 patients (13.8%).

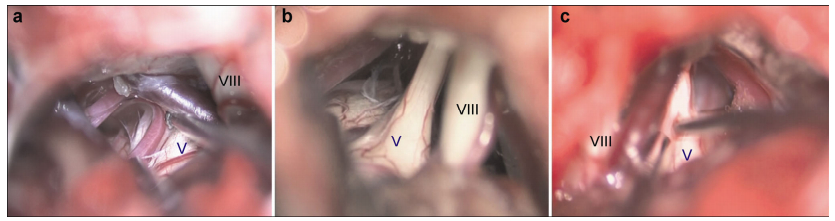

2.2 Microsurgical methods and groupingEach operation was carried out under general anesthesia, with the patient in the lateral decubitus position. A 3 cm × 2 cm retrosigmoid craniotomy was performed. At the connecting point of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses, the dura was shaped cut “^” and sewn hanging. Cerebrospinal fluid was then slowly drained from the paracerebellar cisterns. During the operation, each patient underwent trigeminal nerve decompression (TND), which included the arteries, veins, and the thickened arachnoid membrane from the pons to Meckel’s cave. Based on operational findings and techniques, patients were separated into three treatment groups. Patients who had grossly appreciable indentations in the trigeminal nerves were placed into the trigeminal nerve decompression group (TND group, 19 patients) (Figure 1a). Small sculpted sponge polyesters were then inserted between the nerve and vessel. Patients who had trigeminal nerves without vessel compression and did not have gross indentations in most of the trigeminal nerves were placed into the TND and rhizotomy group (rhizotomy group, 55 patients). The trigeminal nerve was dissociated by coagulating the veins and displacing the artery that touched the nerve, followed by cutting off one-third to two-thirds of the trigeminal nerve sensory root on its dorsolateral side (Figure 1b). Patients who did not have gross indentations in the trigeminal nerves were placed into the TND and selective lesioning group (lesioning group, 35 patients). The trigeminal nerve was dissociated by coagulating the veins and displacing the artery that touched the nerve, followed by the use of a 1 mm nerve detacher with a spherical head to insert into the trigeminal nerve, depending on where the facial pain was (Figure 1c). The nerve detacher was moved forward and backward several times in an oscillatory manner, in order to selectively destroy the trigeminal nerve.

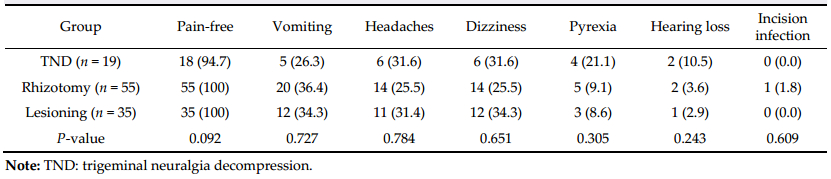

|

| Figure 1 Three group for trigeminal neuragia. (a) The trigeminal nerve was compressed by the artery. (b) The trigeminal nerve without compression needed rhizotomy. (c) The selective lesion was performed on the trigeminal nerve, after decompression. Ⅴ: the trigeminal nerve; Ⅷ: the auditory nerve. |

Short-term surgical outcomes and complications were evaluated by reviewing the medical records. All mid-term data was evaluated through telephone interviews. The telephone interview included two main questions. The first main question was “How is your facial pain presently?” There were three types of answers: ① completely pain-free, no need for medication; ② facial pain decreased after operation, need less medication; ③ facial pain remained the same as before the operation, or the pain relapsed. The second main question was “If you have facial numbness, do you think it impacts your quality of life?” There were two types of answers: ① No, the quality of life did not reduce. There are no signs of facial numbness and no complaints of numbness. ② Yes, the quality of life was reduced due to numbness. There is facial numbness which cannot be tolerated, complaints of swelling in the face, lips, and tongue, and complaints of drooling saliva, tongue biting or mouth mucosa.

2.4 Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using SPSS soft-ware version 13. Group comparisons were performed using Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorized data. Significance was accepted at the 0.05 level.

3 Results 3.1 Short-term surgical outcomes and complications (Table 1)During the hospitalization, 108 patients (99.1%) were completely pain-free and 1 patient (0.9%) had pain relief. There was also no facial paralysis, diplopia, or cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Data showed postopera-tive vomiting in 37 patients (33.9%), headaches in 31 patients (28.4%), dizziness in 32 patients (29.4%), pyrexia in 12 patients (11.0%), and incision infection in 1 patient (0.9%); however, all of these symptoms disappeared before patients left the hospital. Addition-ally, postoperative hearing loss occurred in 5 patients (4.6%); during follow-up, 4 patients had regained normal hearing while 1 patient still had hearing loss. Statistical analysis showed that different microsurgical methods had no effect on the occurrence of vomiting, headaches, dizziness, pyrexia, incision infections, and hearing loss (P > 0.05).

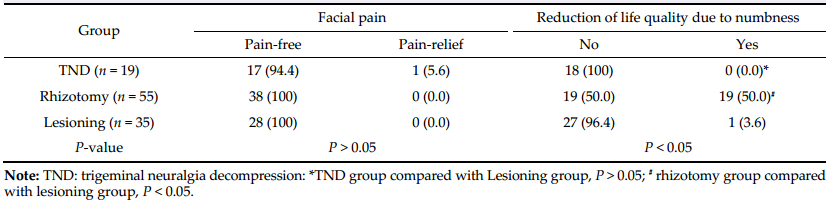

3.2 Mid-term outcomes and numbness (Table 2)Eighty-four patients were followed up through telephone interviews; the follow-up time ranged from 6 to 33 months, with a mean of 17.7 months. In the TND group, 27 of the 28 patients were completely pain-free, and no patient had symptoms of numbness. In the rhizotomy group, all patients were pain-free, but half of the patients thought their quality of life was reduced due to numbness. In the lesioning group, all patients were pain-free, while 1 patient out of 27 thought their quality of life was reduced due to numbness. Based on these statistics, the microsurgical

methods had a significant impact on numbness; the occurrence of numbness was less in the lesioning group compared to the rhizotomy group (P < 0.05), but there were no significant differences between the lesioning and TND groups (P > 0.05).

4 DiscussionSince the 1970s, Jannetta perfected and popularized microvascular decompression (MVD). Vascular compression is widely accepted as the etiology of trigeminal neuralgia, especially in the neurosurgical field. Using this method, 70% of patients reported being pain-free in the long-term[2-4]. The rate of being pain-free at mid-term follow-up was 84%-92.5%[5-7]. The main factor for attaining a high long-term cure rate during MVD was revealing the clear-cut and marked vascular compression[6]. In this study, the follow-up data showed that the rate of being pain-free in the TND group was 94.4%. Firstly, this result could be due to the strict inclusion criteria. Only patients with gross indentations observed were placed into the TND group. In these cases, the vessel responsible for TN was very clear and definite. Secondly, the concept of decompression was expanded in this group. The operation performed was not only decompression of the conflict vessels, but also decompression of the smaller veins and arteries in the surface around the nerve root and pons. It was important to cut off the thickened arachnoid around Meckel’s cave, thus dissociating the fifth nerve. Only one case in this group was not pain-free, and the reason could be that this nerve had problems with self-restoration due to severe nerve damage.

Bederson and Wilson[8] reported that 80% of patients who underwent the combination of MVD and partial sensory rhizotomy (PSR) were pain-free in the long-term. This was higher than patients who underwent only MVD or only PSR, but these differences were not significant. During this study, partial sensory rhizotomy and selective lesioning were performed after TND if the trigeminal nerve did not have gross indentations. In two of the groups, TND may be the reason for no recurrence. The breakage of the trigeminal nerve may be the reason that patients immediately became pain-free after the operations.

In this study, all patients were pain-free after microsurgery in both the rhizotomy and lesioning groups. In the TND group, the rate of becoming pain-free after the operation was 94.4%. This may indicate that artificial lesioning could be a good technique for controlling pain, on the basis of trigeminal nerve decompression. In the lesioning group, the occurrences of numbness were significantly less than in the rhizo-tomy group, but there were no significant differences when compared to the TND group. In addition, there were no significant differences in the frequency of complications between the three groups. Therefore, selective lesioning on the basis of TND could be a good strategy for trigeminal neuralgia, when nerve indentations are not present. It is safer, effective, and improves the quality of patients’ lives.

Revuelta-Gutierrez et al.[9] and Cheng et al.[10] reported that patients without vascular compression underwent trigeminal root compression (minimal trauma). All patients were pain-free after the procedure. In the follow up, the relapse rate ranged from 27% to 38.4%. Compared to these studies, we inflicted more damage on the trigeminal root. We thought this was the reason for no relapse in the lesioning group with respect to pain.

Many studies have reported the complication rates for MVD of TN. Bond et al.[4] reported that no perioperative deaths or major complications, including hearing loss, occurred. Saram et al.[5] reported that transient partial facial palsy was recorded in 0.8% of patients, permanent double vision in 0.5% of patients, and permanent hearing loss in 1.3% of patients. Sandell and Eide[11] reported cerebellar swelling/infarction in 0.7% of the patients, wound infection in 1.5% of patients, and abacterial meningitis in 0.7% of patients. Li et al.[12] reported death in 0.4% of retrosigmoid cranial nerve surgeries, cerebrospinal fluid leakage in 5.6% of patients, and immediate vertigo in 33.3% of patients. Bartek et al.[13] reported permanent hearing loss in 2% of patients, and permanent CN Ⅶ palsy in 1% of patients. In this study, permanent hearing loss appeared in 0.9% of the patients; however, no other permanent complications occurred. The rates of complication were quite different in different departments. They mainly varied according to the surgeon’s personal surgical experience and his/her ability at performing the microsurgical methods. There could be a learning curve for the surgeon who aspires for the “perfect” result and is always critical of their performance[14].

In conclusion, our study found that retrosigmoid surgery was the best choice for treating trigeminal neuralgia. Selective lesioning can ensure both therapeutic efficacy and the improvement of the quality of life in postoperative patients.

5 Conflict of interestsThe authors have no financial interest to disclose regarding the article.

| [1] | Siqueira SR, Teixeira MJ, Siqueira JT. Clinical charac-teristics of patients with trigeminal neuralgia referred to neurosurgery. Eur J Dent , 2009, 3 (3) : 207–212. |

| [2] | Ong KS, Keng SB. Evaluation of surgical procedures for trigeminal neuralgia. Anesth Prog , 2003, 50 (4) : 181–188. |

| [3] | Barker FG, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ, Larkins MV, Jho HD. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med , 1996, 334 (17) : 1077–1083. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199604253341701 |

| [4] | Bond AE, Zada G, Gonzalez AA, Hansen C, Giannotta SL. Operative strategies for minimizing hearing loss and other major complications associated with microvascular decom-pression for trigeminal neuralgia. World Neurosurg , 2010, 74 (1) : 172–177. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2010.05.001 |

| [5] | Sarsam Z, Garcia-Fiñana M, Nurmikko TJ, Varma TRK, Eldridge P. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Br J Neurosurg , 2010, 24 (1) : 18–25. DOI:10.3109/02688690903370289 |

| [6] | Chakravarthi PS, Ghanta R, Kattimani V. Microvascular decompression treatment for trigeminal neuralgia. J Craniofac Surg , 2011, 22 (3) : 894–898. DOI:10.1097/SCS.0b013e31821a07b7 |

| [7] | Tanrikulu L, Hastreiter P, Bassemir T, Bischoff B, Buchfelder M, Dörfler A, Naraghi R. New clinical and morphologic aspects in trigeminal neuralgia. World Neurosurg , 2016, 92 : 189–196. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2016.04.119 |

| [8] | Bederson JB, Wilson CB. Evaluation of microvascular decompression and partial sensory rhizotomy in 252 cases of trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg , 1989, 71 (3) : 359–367. DOI:10.3171/jns.1989.71.3.0359 |

| [9] | Revuelta-Gutierrez R, Martinez-Anda JJ, Coll JB, Campos-Romo A, Perez-Peña N. Efficacy and safety of root compression of trigeminal nerve for trigeminal neuralgia without evidence of vascular compression. World Neurosurg , 2013, 80 (3-4) : 385–389. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2012.07.030 |

| [10] | Cheng J, Lei D, Zhang H, Mao K. Trigeminal root compression for trigeminal neuralgia in patients with no vascular compression. Acta Neurochir (Wien) , 2015, 157 (2) : 323–327. DOI:10.1007/s00701-014-2300-9 |

| [11] | Sandell T, Eide PK. Effect of microvascular decompression in trigeminal neuralgia patients with or without constant pain. Neurosurgery , 2008, 63 (1) : 93–100. DOI:10.1227/01.NEU.0000335075.16858.EF |

| [12] | Li DJ, Wang HB, Fan ZM, Fan Z. Complications in retrosigmoid cranial nerve surgery. Acta Otolaryngol , 2010, 130 (2) : 247–252. DOI:10.3109/00016480903092340 |

| [13] | Bartek J Jr, Gulati S, Unsgård G, Weber C, Förander P, Solheim O, Jakola AS. Standardized reporting of adverse events after microvascular decompression of cranial nerves; a population-based single-institution consecutive series. Acta Neurochir (Wien) , 2016, 158 (9) : 1775–1781. DOI:10.1007/s00701-016-2856-7 |

| [14] | Cohen-Gadol AA. Microvascular decompression surgery for trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm:Naunces of the technique based on experiences with 100 patients and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg , 2011, 113 (10) : 844–853. DOI:10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.06.003 |