文章信息

- 韩鑫, 丁元, 孙忠权, 王伟林

- Han Xin, Ding Yuan, Sun Zhongquan, Wang Weilin

- 肝移植在结直肠癌肝转移中的价值

- Value of liver transplantation for colorectal cancer liver metastases

- 实用肿瘤杂志, 2022, 37(1): 16-22

- Journal of Practical Oncology, 2022, 37(1): 16-22

基金项目

- 国家自然科学基金(81773096,82072650,82001673);浙江省重点研发计划项目(2021C03121)

-

通信作者

- 王伟林,E-mail:wam@zju.edu.cn

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2021-12-31

结直肠癌是全球最为常见的恶性肿瘤之一,位居肿瘤相关发病率第三位,也是肿瘤相关的第二大致死原因。据统计,2020年我国新发结直肠癌约56万例,死亡约29万例[1]。肝脏是结直肠癌最常见的远处转移部位,15%~25%的结直肠癌患者初诊时已伴随肝脏转移,18%~25%的患者在早期诊断为结直肠癌后的5年内也发生了肝脏转移[2-3]。传统的“三明治”疗法,即新辅助治疗-手术切除-辅助化疗,被认为是结直肠癌肝转移的标准治疗模式,但患者5年总生存率仍低于60%,且术后复发率高,严重影响患者的预后水平[4-6]。此外,近一半患者失去手术机会,姑息性治疗是其唯一的选择,5年总生存率低于10%[7-9]。因此,亟需探索新的有效治疗方式和策略,突破不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者的治疗困境。

近年来,肝移植作为新兴的治疗方式在不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移的治疗领域中逐渐受到世界各地专家的广泛关注。早在20世纪90年代,奥地利维也纳医科大学F. Mühlbacher团队率先开展了单中心研究,纳入了从1982年至1994年的25例接受肝移植的不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者,其1、3和5年总生存率分别为76%、32%和12%,移植后30 d死亡率高达30%[10-12]。与此同时,欧洲肝移植注册中心1977年至1995年的数据显示,对于初始不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者,共施行肝移植58例,其中1、3和5年总生存率分别为73%、36%和18%,且值得注意的是,44%的患者在肿瘤未复发之前就已出现移植物功能衰竭[13-15]。由于初始探索的结果不理想且缺乏标准的免疫抑制方案、严格的患者筛选标准和成熟的肝移植技术,肝移植应用于不可切除性结直肠癌的研究逐渐迈入冰点[16-17]。

然而,在2006年,挪威奥斯陆大学医院开展了一项开放、前瞻性的试验性研究(SECA Trail),旨在评估肝移植治疗不可切除性结直肠癌的疗效,因其突破性结果而引起了广泛关注[18]。在SECA Ⅰ研究中,共纳入25例患者,其中4例因患有肝外疾病而退出,具体入组标准为:(1)原发病灶R0切除;(2)至少接受化疗6周;(3)无不可切除性肝外转移灶;(4)ECOG评分0或1。通过27个月的中位随访时间,结果显示,患者1、3和5年总生存率分别为95%、68%和60%。在此基础上,进一步分析发现,患者预后与肿瘤大小及生物学行为密切相关,综合四大预后预测因素,提出Oslo评分,即为:(1)肿瘤最大直径>5.5 cm;(2)移植前癌胚抗原(carcinoembryonic antigen,CEA)>80 μg/L;(3)化疗后疾病进展;(4)从诊断到肝移植间隔<2年[18-19]。2011年,SECA Ⅱ临床试验注册启动,该期研究制定了更为严格的纳入标准,要求肝转移灶对化疗的反应>10%,且确诊至肝移植的间隔>1年[20]。结果显示,在中位随访时间为36个月的前提下,1、3和5年总生存率分别为100%、100%和83%,且1、2和3年无瘤生存率分别为53%、44%和35%。目前,SECA Ⅰ(NCT00294827)和SECA Ⅱ临床试验(NCT01479608)仍在进行中,因其出色的阶段性结果,再次把肝移植引入到不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移的治疗队列之中,但仍面临许多困境与难题。本文将围绕以下4个问题开展相关讨论。

1 与标准的姑息性化疗比较,肝移植是否更有优势?2015年,挪威奥斯陆大学医院Svein Dueland团队将SECA Ⅰ试验队列和NORDIC Ⅶ试验队列进行比较,该回顾性研究纳入NORDIC Ⅶ试验中47例仅接受化疗的仅肝脏转移的结直肠癌患者和SECA Ⅰ试验中21例行肝移植的结直肠癌肝转移患者[21-22]。SECA Ⅰ研究和NORDIC Ⅶ研究患者除CEA水平(15 μg/L vs 42 μg/L,P<0.01)外, 其他基线数据比较差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。而在结局方面,SECA Ⅰ研究中患者5年生存率高于NORDIC Ⅶ研究中生存时间最长的21例患者(56% vs 19%,P<0.01)[21]。此外,另一项纳入三项非随机对照试验共48例患者的系统性综述同样提示,相较于姑息性化疗,肝移植具备潜在改善不可切除性结直肠癌患者长期预后的临床价值[23]。

由于以上研究所纳入的证据级别较低,且存在明显偏倚,因此,一些高质量的随机对照临床试验陆续开展,以明确肝移植疗法在不可切除性结直肠癌中的临床价值。法国巴黎萨伯特医院在2016年2月开始开展了一项比较肝移植联合化疗与仅接受化疗在不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移中的多中心、前瞻性、随机对照临床试验(TRANSMET试验,NCT02597348),该试验入组94例患者,是目前比较肝移植与标准化疗疗效的临床试验中样本量最大的一项研究。同年,挪威奥斯陆大学医院于12月开展SECA Ⅲ临床试验(NCT03494946),这项随机对照试验旨在评估肝移植与化疗为主的姑息治疗对不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者的疗效。此后,一系列相关临床试验在世界各地陆续开展(NCT02864485、NCT03803436和NCT04161092等),均制定了严格的入组标准和排除标准,希望为肝移植在结直肠癌肝转移的应用提供高质量的证据。

2 严格筛选后的患者行肝移植能否获得长期生存?一项来自欧洲肝胆联盟的回顾性研究证实,针对严格筛选的不可切除性结直肠癌患者,肝移植可提供良好的生存获益,患者的1、3和5年总生存率分别为83%、62%和50%,且三分之一的患者在肝移植后2年内未复发[24]。虽然该研究仅是小规模回顾性研究(n=12),但其结果是鼓舞人心的。近期,一项纳入18项研究共110例患者的系统性研究揭示,基于严格的患者筛选和规范的外科治疗,不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者应考虑肝移植;结合亚组分析,随着肝移植技术的不断提升,2005年后行肝移植的患者1、3和5年总生存率分别高达94.5%、71.8%和65.8%,1、3和5年无复发生存率分别为46.8%、25.6%和25.6%[25]。

挪威奥斯陆大学医院Svein Dueland团队深度分析并比较了三种评分系统(表 1)在预测不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者肝移植术后长期生存水平的能力,结果显示,移植前Oslo评分0~2,代谢性肿瘤体积(metabolic tumour volume, MTV)值<70 cm3,Fong临床风险评分(Fong Clinical Risk Score, FCRS)为0~2,5年总生存率分别高达67%、78%和100%[26]。因此,这三种评分系统在一定程度上可作为筛选不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者采取肝移植治疗的重要参考[19]。

| 评分标准 | 具体内容 | 赋值 |

| Oslo评分 | 肿瘤最大直径>5.5 cm | 1 |

| 移植前CEA>80 μg/L | 1 | |

| 化疗后疾病进展 | 1 | |

| 从诊断到肝移植间隔<2年 | 1 | |

| MTV | 所有>40% SUVmax的病灶体积 | <70 cm3 |

| FCRS | 淋巴结阳性 | 1 |

| 诊断至肝转移的间隔时间<12个月 | 1 | |

| >1处肝转移灶 | 1 | |

| 术前CEA>200 μg/L | 1 | |

| 肿瘤最大直径>5.0 cm | 1 | |

| 注 MTV: 代谢性肿瘤体积(metabolic tumour volume);Fong临床风险评分(Fong Clinical Risk Score);CEA:癌胚抗原(carcinoembryonic antigen);SUVmax:18F-FDG PET扫描的最大标准摄取值(maximum standard uptake value) | ||

在SECA Ⅰ试验中,几乎所有的患者在2年内均出现了肿瘤复发。尽管SECA Ⅱ研究制定了更为严格的入组标准,但是仍有近65%的患者在3年内复发[18, 20]。相似的移植后高肿瘤复发率也被多项研究所证实[24-25]。但值得注意的是,70%的复发是小且生长缓慢的肺部转移,且60%的肺部转移灶是可以被R0切除的。更关键的是,即使肿瘤复发,患者的复发后4年总生存率仍高达73%[20, 27]。此外,与部分肝切除治疗不同的是,肝移植后患者的多发转移率明显降低,且肝脏复发率极低,仅为3%[28]。同时,回顾性研究发现约40%的肝外转移很可能在肝移植前已经发生[27]。因此,目前尚不清楚不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者行肝移植后出现的肿瘤复发中有多少属于真正的复发,有多少是代表分期失败。不幸的是,目前尚缺乏敏感和特异的方法来检测和诊断结直肠癌肝转移患者中的微小肺转移灶。

传统的免疫抑制方案由于其多种不同的机制可能会增加肿瘤复发进展的风险,因而有学者怀疑移植后高复发率与全身免疫抑制状态有关[29]。挪威奥斯陆大学医院H. Grut团队开展了一项评估免疫抑制治疗是否会加速不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者中肺转移灶生长的研究,有趣的是,免疫抑制治疗对移植组患者的肿瘤进展没有负面影响,且血浆西罗莫司浓度与患者的无瘤生存期及肺转移灶的生长速率无明显相关性[30-31]。因此,目前并没有有力证据证明免疫抑制剂的使用可增加肿瘤复发的风险。但由于该方面的研究规模较小且存在偏倚,未来需要更多的研究来解决这一难题。

4 肝源紧缺下,如何增加供肝来源?近年来,供体短缺的问题深深地影响着全球各个地区,等待移植的患者例数与可供移植的器官数量之间的差距正在不断扩大[32]。为了扩大供肝池,边缘性肝源,如循环死亡后的捐献(donation after circulatory death,DCD)[33]、老年肝[34]、脂肪肝[35]或者丙肝病毒感染的肝脏[36],或将成为可能的供肝来源。但由于这些肝源在移植后会增加并发症发生的风险,容易引起早期移植物功能障碍甚至失去功能和胆管相关并发症等,使得边缘性肝移植在目前仍存在争议[37]。

除此之外,一些先进的外科技术也在不断探索之中。劈裂式肝移植,即“一肝两用”,可为更多的等待移植患者提供肝源,且劈离方式多样,未来可能成为供肝的主要来源之一[38-39]。经典的劈裂肝,即将肝脏分为左外侧叶(Ⅱ+Ⅲ段)和扩展右叶(Ⅰ+Ⅳ~Ⅷ段),左外侧叶肝用于儿童或小型成人受体,而扩展右叶肝则用于成人受体。另一种则将肝脏分为左叶(Ⅰ~Ⅳ段)和右叶(Ⅳ~Ⅷ段),两叶均可用于成人受体[38, 40]。值得一提的是,扩展右叶肝移植可以是传统全肝移植的主要替代方案,且在一定条件下可以完美替代[41]。

此外,活体肝移植,即供体捐献一部分肝脏予受体,而自身留下足够的剩余肝脏来供自身长期生活,引起了世界学者的广泛关注。由于其理论上可提供无限的肝源,极大地缩短患者等待时间,目前已成为有经验中心的一种安全和流行的手术技术[32, 42]。右叶肝最常用于成人对成人的活体肝移植,左叶肝常用于成人对儿童的活体肝移植。而近年来也有许多中心提倡将左叶肝用于成人对成人的活体肝移植[43-44]。体积研究表明,多数的右后叶肝或右外侧叶肝比左叶肝大,使得其作为移植物也成为可能[45]。由于没有切除体积较大的右前叶和左叶肝,供体依旧可以保留足够的剩余肝体积,同时进一步研究表明,18%供体的右后叶肝可用于活体肝移植[46-47]。

对于不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移,挪威奥斯陆大学医院率先发明了“双阶段肝移植”外科技术[肝切除联合部分肝移植的延期全肝切除(resection and partial liver segment 2/3 transplantation with delayed total hepatectomy, RAPID)][48]。在第一阶段,受体肝脏Ⅰ~Ⅲ段切除,移植物(Ⅱ~Ⅲ段肝)植入,并将门静脉血流从固有残体转移到移植物,促进肝脏快速再生;在第二阶段,当移植物体积约为标准肝脏体积的35%~40%时,切除残余肝脏,仅留下移植肝脏[48]。随后,RAPID手术概念逐渐被应用到活体肝移植当中。据报道,辅助活体供肝移植联合两期肝切除术[活体RAPID(living donor RAPID, LD-RAPID)]被认为是可行且安全的,有可能成为不可切除性结直肠癌的治疗新范式,但目前只有个案报道,尚且缺乏有力证据,使得其在该领域的应用仍具有巨大的挑战性[49-50]。因此,为了评估RAPID/LD-RAPID手术理念的有效性及适用性,相关临床研究(NCT02215889和NCT03488953)也在进行当中。

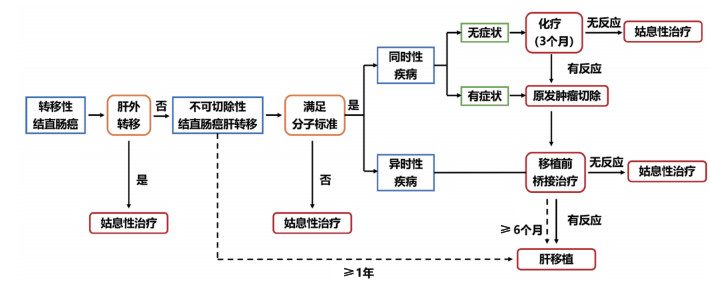

综上所述,越来越多的研究肯定了肝移植在严格筛选条件下可改善不可切除性结直肠癌患者预后的价值,并围绕目前存在的困境与争议展开大量临床研究以全面评估肝移植的安全性与有效性,使得肝移植在未来有可能成为不可切除性结直肠癌的标准治疗之一[51]。2021年9月,国际肝胆胰协会发布了不可切除性结直肠癌行肝移植的指南共识,规范了一系列标准化术语定义,制定了患者选择标准(表 2)、移植前患者生物学行为评估策略、移植物选择与分配原则、受体考虑因素和预期预后水平标准[52]。同时,该共识建立了不可切除性结直肠肝转移肝移植的安全治疗框架(图 1),为未来更好的患者选择和器官分配的实践研究打下坚实的基础,从而提高不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移患者的长期生存。

| 标准类别 | 具体内容 |

| 临床选择标准 | (1)不可切除性结直肠癌肝转移或原发灶切除后复发肝转移患者。 (2)原发肿瘤切除,至少包括1 mm的周切缘在内的切缘阴性。 (3)对于肝内多发转移或肝转移灶较大或两者兼有的患者应谨慎。 (4)几乎没有证据支持肝移植用于可切除性疾病。 (5)暂没有证据支持最初存在或随后发展为肝外/结直肠外转移的患者可行肝移植。 |

| 影像学标准 | (1)初始肝转移灶的可切除性应通过肝脏MRI或CT或两者联合评估。 (2)建议行高分辨率CT胸部检查以排除肺转移。 (3)18F-FDG PET-CT可评估代谢肿瘤体积和病灶总糖酵解量;代谢肿瘤体积为>70 cm3,病灶总糖酵解量为>260 g的患者应排除。 (4)18F-FDG PET-CT被推荐用于排除肝外转移灶,当临床怀疑程度高且术前PET成像不确定时,应考虑系统性淋巴结穿刺。 |

| 病理标准 | (1)排除原发肿瘤组织学为未分化腺癌和印戒细胞癌。 (2)相对排除原发肿瘤淋巴结N2转移的患者。 |

| 分子生物学标准 | (1)对于BRAF和RAS突变以及微卫星不稳定和存在错配修复状态的患者应警惕。 (2)BRAF V600E突变的患者应排除。 (3)如存在其他有利的生物学因素,RAS突变的患者也可考虑肝移植。 (4)由于免疫治疗对微卫星不稳定和(或)存在错配修复状态的患者效果良好,故此类患者暂不考虑肝移植。 |

| 注 BRAF:V-raf鼠肉瘤病毒癌基因同源体B(V-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) | |

| [1] |

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020:GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249. DOI:10.3322/caac.21660 |

| [2] |

van der Geest LGM, Lam-Boer J, Koopman M, et al. Nationwide trends in incidence, treatment and survival of colorectal cancer patients with synchronous metastases[J]. Clin Exp Metastasis, 2015, 32(5): 457-465. DOI:10.1007/s10585-015-9719-0 |

| [3] |

van Gestel YRBM, de Hingh IHJT, van Herk-Sukel MPP, et al. Patterns of metachronous metastases after curative treatment of colorectal cancer[J]. Cancer Epidemiol, 2014, 38(4): 448-454. DOI:10.1016/j.canep.2014.04.004 |

| [4] |

House MG, Ito H, Gönen M, et al. Survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: trends in outcomes for 1, 600 patients during two decades at a single institution[J]. J Am Coll Surg, 2010, 210(5): 744-752. DOI:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.040 |

| [5] |

Viganò L, Capussotti L, Lapointe R, et al. Early recurrence after liver resection for colorectal metastases: risk factors, prognosis, and treatment. A LiverMetSurvey-based study of 6, 025 patients[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2014, 21(4): 1276-1286. DOI:10.1245/s10434-013-3421-8 |

| [6] |

Wei AC, Greig PD, Grant D, et al. Survival after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases: a 10-year experience[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2006, 13(5): 668-676. DOI:10.1245/ASO.2006.05.039 |

| [7] |

Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C, et al. Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer[J]. Ann Surg, 2006, 244(2): 254-259. DOI:10.1097/01.sla.0000217629.94941.cf |

| [8] |

van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2009, 360(14): 1408-1417. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0805019 |

| [9] |

Sanoff HK, Sargent DJ, Campbell ME, et al. Five-year data and prognostic factor analysis of oxaliplatin and irinotecan combinations for advanced colorectal cancer: N9741[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2008, 26(35): 5721-5727. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7147 |

| [10] |

Mühlbacher F, Huk I, Steininger R, et al. Is orthotopic liver transplantation a feasible treatment for secondary cancer of the liver?[J]. Transpl Proc, 1991, 23(1 Pt 2): 1567-1568. |

| [11] |

Mühlbacher F, Piza F. Orthotopic liver transplantation for secondary malignancies of the liver[J]. Transplant Proc, 1987, 19(1 Pt 3): 2396-2398. |

| [12] |

Moris D, Tsilimigras DI, Chakedis J, et al. Liver transplantation for unresectable colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review[J]. J Surg Oncol, 2017, 116(3): 288-297. DOI:10.1002/jso.24671 |

| [13] |

Foss A, Adam R, Dueland S. Liver transplantation for colorectal liver metastases: revisiting the concept[J]. Transpl Int, 2010, 23(7): 679-685. DOI:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2010.01097.x |

| [14] |

Hoti E, Adam R. Liver transplantation for primary and metastatic liver cancers[J]. Transpl Int, 2008, 21(12): 1107-1117. DOI:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00735.x |

| [15] |

Andersen MH, Dueland S, Hagness M, et al. Quality of life following liver transplantation in patients with liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma[J]. Scand J Caring Sci, 2012, 26(4): 713-719. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00984.x |

| [16] |

Kow AWC. Hepatic metastasis from colorectal cancer[J]. J Gastrointest Oncol, 2019, 10(6): 1274-1298. DOI:10.21037/jgo.2019.08.06 |

| [17] |

Gorgen A, Muaddi H, Zhang W, et al. The new era of transplant oncology: liver transplantation for nonresectable colorectal cancer liver metastases[J]. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 2018: 9531925. |

| [18] |

Hagness M, Foss A, Line PD, et al. Liver transplantation for nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer[J]. Ann Surg, 2013, 257(5): 800-806. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182823957 |

| [19] |

Line PD, Dueland S. Liver transplantation for secondary liver tumours: the difficult balance between survival and recurrence[J]. J Hepatol, 2020, 73(6): 1557-1562. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2020.08.015 |

| [20] |

Dueland S, Syversveen T, Solheim JM, et al. Survival following liver transplantation for patients with nonresectable liver-only colorectal metastases[J]. Ann Surg, 2020, 271(2): 212-218. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003404 |

| [21] |

Dueland S, Guren TK, Hagness M, et al. Chemotherapy or liver transplantation for nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer?[J]. Ann Surg, 2015, 261(5): 956-960. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000786 |

| [22] |

Tveit KM, Guren T, Glimelius B, et al. Phase Ⅲ trial of cetuximab with continuous or intermittent fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (Nordic FLOX) versus FLOX alone in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: the NORDIC-Ⅶ study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2012, 30(15): 1755-1762. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2011.38.0915 |

| [23] |

Varley R, Tarazi M, Davé M, et al. Liver transplantation for non-resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. World J Surg, 2021, 45(11): 3404-3413. DOI:10.1007/s00268-021-06248-4 |

| [24] |

Toso C, Marques HP, Andres A, et al. Liver transplantation for colorectal liver metastasis: survival without recurrence can be achieved[J]. Liver Transpl, 2017, 23(8): 1073-1076. DOI:10.1002/lt.24791 |

| [25] |

Giannis D, Sideris G, Kakos CD, et al. The role of liver transplantation for colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review and pooled analysis[J]. Transplant Rev (Orlando), 2020, 34(4): 100570. DOI:10.1016/j.trre.2020.100570 |

| [26] |

Dueland S, Grut H, Syversveen T, et al. Selection criteria related to long-term survival following liver transplantation for colorectal liver metastasis[J]. Am J Transplant, 2020, 20(2): 530-537. DOI:10.1111/ajt.15682 |

| [27] |

Hagness M, Foss A, Line PD, et al. Liver transplantation for nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer[J]. Ann Surg, 2013, 257(5): 800-806. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182823957 |

| [28] |

Line PD, Ruffolo LI, Toso C, et al. Liver transplantation for colorectal liver metastases: what do we need to know?[J]. Int J Surg, 2020, 82: 87-92. |

| [29] |

Geissler EK, Schlitt HJ. Immunosuppression for liver transplantation[J]. Gut, 2009, 58(3): 452-463. DOI:10.1136/gut.2008.163527 |

| [30] |

Grut H, Solberg S, Seierstad T, et al. Growth rates of pulmonary metastases after liver transplantation for unresectable colorectal liver metastases[J]. Br J Surg, 2017, 105(3): 295-301. |

| [31] |

Glinka J, Ardiles V, Pekolj J, et al. Liver transplantation for non-resectable colorectal liver metastasis: where we are and where we are going[J]. Langenbeck's Arch Surg, 2020, 405(3): 255-264. DOI:10.1007/s00423-020-01883-2 |

| [32] |

Sapisochin G, Bruix J. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: outcomes and novel surgical approaches[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017, 14(4): 203-217. DOI:10.1038/nrgastro.2016.193 |

| [33] |

Selck FW, Grossman EB, Ratner LE, et al. Utilization, outcomes, and retransplantation of liver allografts from donation after cardiac death[J]. Ann Surg, 2008, 248(4): 599-607. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a080e |

| [34] |

Lué A, Solanas E, Baptista P, et al. How important is donor age in liver transplantation?[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22(21): 4966-4976. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v22.i21.4966 |

| [35] |

McCormack L, Dutkowski P, El-Badry AM, et al. Liver transplantation using fatty livers: always feasible?[J]. J Hepatol, 2011, 54(5): 1055-1062. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.004 |

| [36] |

Bowring MG, Kucirka LM, Massie AB, et al. Changes in utilization and discard of hepatitis C-infected donor livers in the recent era[J]. Am J Transplant, 2017, 17(2): 519-527. DOI:10.1111/ajt.13976 |

| [37] |

Busuttil RW, Tanaka K. The utility of marginal donors in liver transplantation[J]. Liver Transpl, 2003, 9(7): 651-663. DOI:10.1053/jlts.2003.50105 |

| [38] |

Hackl C, Schmidt KM, Susal C, et al. Split liver transplantation: Current developments[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2018, 24(47): 5312-5321. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v24.i47.5312 |

| [39] |

Broering DC, Esch JSA, Fischer L, et al. Split liver transplantation[J]. HPB, 2004, 6(2): 76-82. DOI:10.1080/13651820310020774 |

| [40] |

Patil NS, Goyal N, Pareek S, et al. In situ splitting of the cadaver liver for two adult recipients by LDLT technique[J]. J Clin Exp Hepatol, 2017, 7(3): 179-183. DOI:10.1016/j.jceh.2017.05.001 |

| [41] |

Lozanovski VJ, Unterrainer C, Döhler B, et al. Outcome of extended right lobe liver transplantations[J]. Liver Transpl, 2021, Epub.

|

| [42] |

Rossler F, Sapisochin G, Song G, et al. Defining benchmarks for major liver surgery: a multicenter analysis of 5202 living liver donors[J]. Ann Surg, 2016, 264(3): 492-500. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001849 |

| [43] |

Halazun KJ, Przybyszewski EM, Griesemer AD, et al. Leaning to the left: increasing the donor pool by using the left lobe, outcomes of the largest single-center North American experience of left lobe adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation[J]. Ann Surg, 2016, 264(3): 448-456. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001860 |

| [44] |

Goldaracena N, Barbas AS. Living donor liver transplantation[J]. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2019, 24(2): 131-137. DOI:10.1097/MOT.0000000000000610 |

| [45] |

Leelaudomlipi S, Sugawara Y, Kaneko J, et al. Volumetric analysis of liver segments in 155 living donors[J]. Liver Transpl, 2002, 8(7): 612-614. DOI:10.1053/jlts.2002.33731 |

| [46] |

Chen CL. The right posterior sector graft in living donor liver transplantation revisited[J]. Liver Transpl, 2014, 20(9): 1019-1020. DOI:10.1002/lt.23967 |

| [47] |

Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, et al. Right lateral sector graft in adult living-related liver transplantation[J]. Transplantation, 2002, 73(1): 111-114. DOI:10.1097/00007890-200201150-00021 |

| [48] |

Line PD, Hagness M, Berstad AE, et al. A novel concept for partial liver transplantation in nonresectable colorectal liver metastases: the RAPID concept[J]. Ann Surg, 2015, 262(1): e5-e9. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001165 |

| [49] |

Nadalin S, Königsrainer A, Capobianco I, et al. Auxiliary living donor liver transplantation combined with two-stage hepatectomy for unresectable colorectal liver metastases[J]. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2019, 24(5): 651-658. DOI:10.1097/MOT.0000000000000695 |

| [50] |

Königsrainer A, Templin S, Capobianco I, et al. Paradigm shift in the management of irresectable colorectal liver metastases[J]. Ann Surg, 2019, 270(2): 327-332. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002861 |

| [51] |

Puia-Negulescu S, Lebossé F, Mabrut JY, et al. Liver transplantation for colorectal liver metastases: current management and future perspectives[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22(6): 3093. DOI:10.3390/ijms22063093 |

| [52] |

Bonney GK, Chew CA, Lodge P, et al. Liver transplantation for non-resectable colorectal liver metastases: the International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association consensus guidelines[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021, 6(11): 933-946. DOI:10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00219-3 |

2022, Vol. 37

2022, Vol. 37