文章信息

- 姜玉娟, 周思成, 裴炜, 毕建军, 周海涛, 刘骞, 梁建伟, 周志祥

- Jiang Yujuan, Zhou Sicheng, Pei Wei, Bi Jianjun, Zhou Haitao, Liu Qian, Liang Jianwei, Zhou Zhixiang

- 73例结直肠GIST临床病理特征及预后分析

- Clinicopathological characteristics and prognostic analysis of 73 cases of colorectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- 实用肿瘤杂志, 2022, 37(6): 543-548

- Journal of Practical Oncology, 2022, 37(6): 543-548

-

通信作者

- 梁建伟,E-mail: liangjw1976@163.com

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2021-08-05

胃肠道间质瘤(gastrointestinal stromal tumor,GIST)是胃肠道最常见的间叶源性肿瘤,来源于胃肠道Cajal细胞或其前体细胞。GIST主要发生在胃及小肠,直肠是其第三好发部位,结肠发病罕见[1]。由于发病率低,病例资料稀缺,结直肠GIST的预后因素尚未充分阐明。本文旨在回顾性分析中国医学科学院北京协和医学院肿瘤医院收治的73例结直肠GIST临床病理资料并探讨其预后因素,以期为临床诊治提供依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 研究对象回顾性分析中国医学科学院北京协和医学院肿瘤医院结直肠外科2000年1月至2021年1月收治的结直肠GIST临床病理资料。纳入标准:(1)病理诊断为结直肠GIST;(2)常规螺旋CT或MRI检查提示无远处转移;(3)结直肠GIST初诊病例。排除标准:(1)患有严重的心脑血管疾病等其他系统疾病不能耐受手术治疗;(2)合并有其他恶性肿瘤。依据上述标准,共73例结直肠GIST患者入组。本研究的设计及开展经过中国医学科学院北京协和医学院肿瘤医院伦理委员会审批通过。所有患者均签署知情同意书。

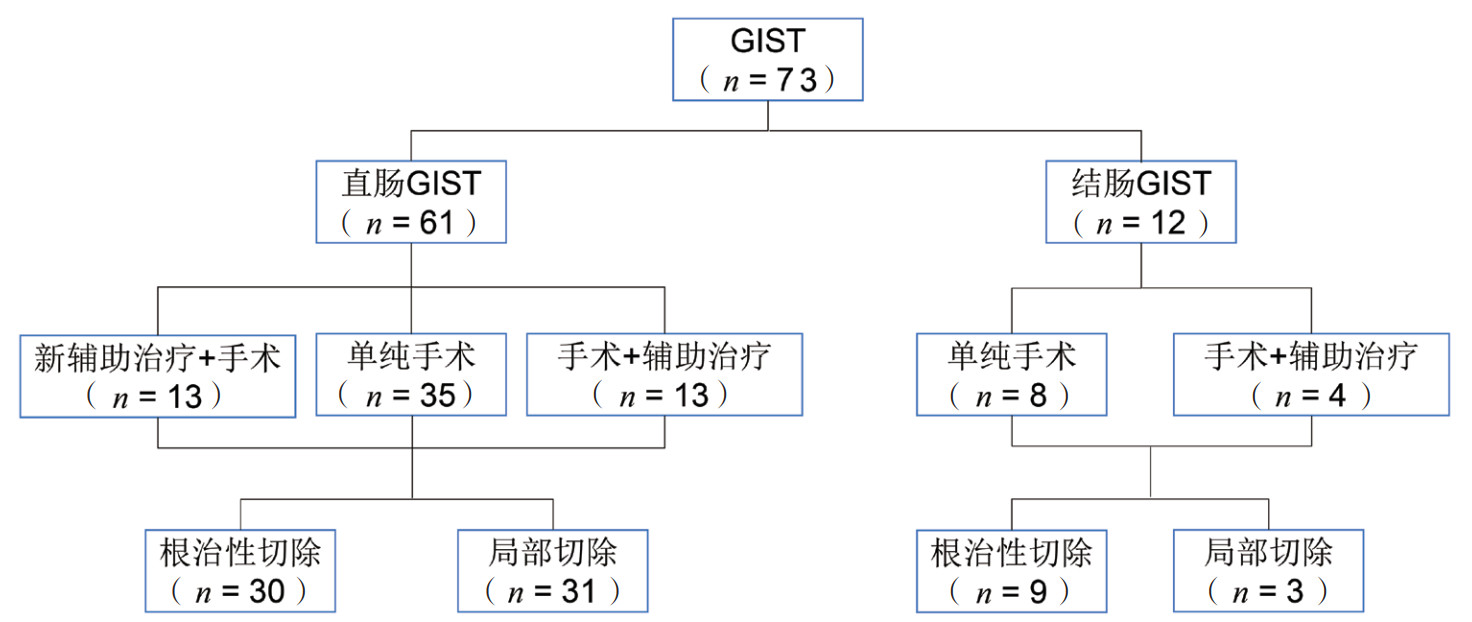

1.2 治疗方案全组患者均接受手术切除。34例(46.6%)行局部切除术,39例(53.4%)行根治性切除术。13例患者术前活检明确间质瘤诊断,接受伊马替尼新辅助治疗(400 mg/d),每3个月依据Choi标准评估疗效[2],连续2次CT或MRI检查肿瘤无显著变化时行手术切除。25例在术后接受伊马替尼(400 mg/d)辅助治疗(包括已接受新辅助治疗的8例)。治疗方案见图 1。

|

| 注 GIST:胃肠道间质瘤(gastrointestinal stromal tumor) 图 1 73例结直肠GIST患者治疗方案图 Fig.1 Treatment plans of 73 patients with colorectal GISTs |

采用门诊与电话结合的方式随访,末次随访日期为2021年5月31日。主要观察指标为无瘤生存期(disease free survival,DFS),定义为手术之日至患者复发转移或末次随访日的时间。随访 > 2年者54例(74.0%),随访 > 5年者39例(53.4%)。

1.4 统计学分析采用SPSS 26.0统计学软件进行数据分析。计量资料采用均数±标准差(x±s)表示。计数资料采用频数(百分比)表示。Kaplan-Meier法绘制生存曲线,Log-rank检验进行预后单因素分析,单因素分析中P < 0.1的变量纳入Cox比例风险回归模型(Forward LR)。以P=0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 一般资料73例结直肠GIST患者发生于结肠12例(16.4%),直肠61例(83.6%),见表 1。男性47例,女性26例。年龄18~77岁,(52.1±11.8)岁;其中≤60岁55例(75.3%)。瘤体直径(3.9±2.4)cm。29例肿瘤位于前壁(39.8%),24例(32.9%)位于侧壁,11例(15.1%)位于后壁,4例(5.5%)累及肠壁全周。全组患者于术前1周内进行血常规检查,RDW值为(13.0±0.0)%。

| 临床特征 | 例数(%) |

| 年龄(岁,x±s) | 52.1±11.8 |

| ≤60岁 | 55(75.3) |

| > 60岁 | 18(24.7) |

| 性别 | |

| 男性 | 47(64.4) |

| 女性 | 26(35.6) |

| 肿瘤位置 | |

| 前壁 | 29(39.8) |

| 侧壁 | 24(32.9) |

| 后壁 | 11(15.1) |

| 全周 | 4(5.5) |

| 未知 | 5(6.9) |

| 肿瘤部位 | |

| 直肠 | 61(83.6) |

| 结肠 | 12(16.4) |

| 瘤体直径(cm,x±s) | 3.9±2.4 |

| ≥5 cm | 24(32.9) |

| < 5 cm | 49(67.1) |

| 术前RDW(%,x±s) | 13.0±0.04 |

| < 13% | 28(38.4) |

| ≥13% | 37(50.7) |

| 未知 | 8(11.0) |

| NIH危险度分级 | |

| 极低/低 | 29(39.7) |

| 中/高 | 44(60.3) |

| 手术方式 | |

| 局部切除术 | 34(46.6) |

| 根治切除术 | 39(53.4) |

| 是否累及周围器官 | |

| 累及阴道 | 5(6.8) |

| 累及前列腺 | 2(2.7) |

| 未累及 | 66(90.4) |

| 术后并发症 | |

| 有 | 14(19.2) |

| 无 | 59(80.8) |

| 辅助治疗 | |

| 是 | 25(34.2) |

| 否 | 41(56.2) |

| 未知 | 7(9.6) |

| 注 GIST:胃肠道间质瘤(gastrointestinal stromal tumor);RDW:术前红细胞分布宽度(red blood cell distribution width);NIH:美国国立卫生研究院(National Institutes of Health) | |

全组患者均接受手术切除,术中未发现肿瘤破裂,经组织病理学证实GIST诊断。7例肿瘤侵犯周围脏器(阴道5例,前列腺2例)。按照2008年美国国立卫生研究院(National Institutes of Health, NIH)改良版危险度分级[3]:极低/低危29例(39.7%),中/高危44例(60.3%)。免疫组织化学染色提示:cluster of differentiation 117(CD117)阳性57例,CD34阳性56例,discovered on GIST-1(DOG-1)阳性31例,S100 proteins(S-100)阳性23例,琥珀酸脱氢酶B(succinate dehydrogenase B,SDH)阳性18例,抗平滑肌抗体(smooth muscle antibody,SMA)阳性14例。8例高危患者进行基因检测,6例存在Kit基因11号外显子突变(缺失突变4例,插入突变1例,剪接突变1例),1例Kit基因13号外显子突变,1例Kit基因9号外显子突变。

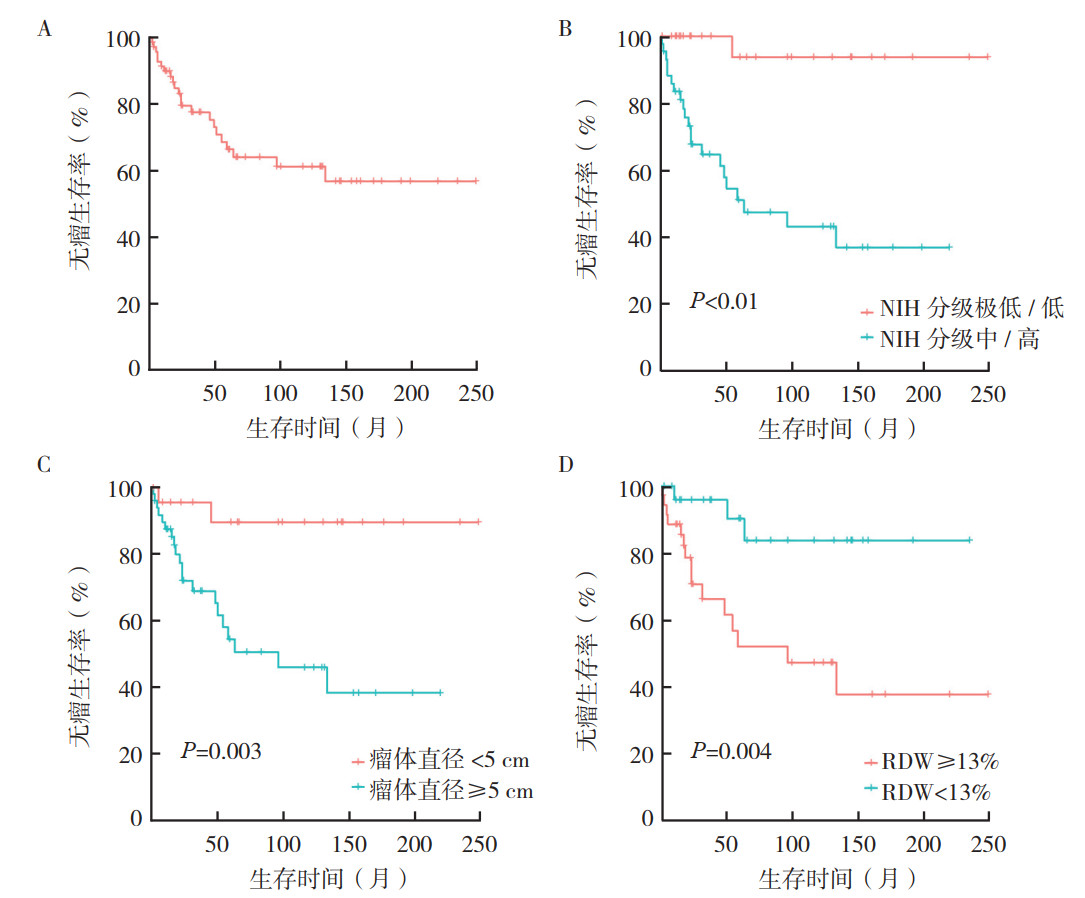

2.3 随访结果中位随访时间66个月。随访发现肿瘤复发18例,远处转移4例(肺转移2例,肝转移2例),因肿瘤死亡4例。3年DFS率为77.6%,5年DFS率为66.5%,截至末次随访日期未观测到中位DFS(图 2A)。本组13例术前评估难以达到R0切除的患者接受新辅助治疗,治疗后肿瘤降期满意均获得R0切除;25例接受术后伊马替尼辅助治疗的患者3年(85.0% vs 73.7%,P=0.336)及5年DFS率(69.5% vs 64.5%,P=0.336)均有增加趋势,但差异均无统计学意义。

|

| 注 A:73例结直肠GIST患者无瘤生存曲线;2B:不同NIH危险度分级患者无瘤生存曲线比较;C:不同瘤体直径患者无瘤生存曲线比较;D:不同RDW水平患者无瘤生存曲线比较;GIST:胃肠道间质瘤(gastrointestinal stromal tumor);NIH:美国国立卫生研究院(National Institutes of Health);RDW:术前红细胞分布宽度(red blood cell distribution width) 图 2 73例结直肠GIST患者无瘤生存曲线及不同临床病理特征对无瘤生存的影响 Fig.2 Disease-free survival curve of 73 patients with colorectal GISTs and the influence of different clinicopathological features on disease-free survival |

单因素分析提示瘤体直径≥5 cm(P=0.003)、术前RDW≥13%(P=0.004)、中/高危NIH危险度分级(P < 0.01)与DFS相关(图 2B~2D,表 2)。以P < 0.1的变量纳入Cox比例风险回归模型,多因素分析提示,NIH危险度分级(HR=15.92,95%CI:2.11~120.32,P=0.007)及术前RDW(HR=0.21,95%CI:0.06~0.72,P=0.014)是影响DFS的独立危险因素(表 2)。

| 临床特征 | 单因素分析 | 多因素分析 | ||||||

| 3年DFS(%) | 5年DFS(%) | χ2值 | P值 | HR | 95%CI | P值 | ||

| 年龄 | 0.91 | 0.340 | ||||||

| ≤60岁 | 82.0 | 71.1 | ||||||

| > 60岁 | 60.3 | 48.2 | ||||||

| 性别 | 0.07 | 0.787 | ||||||

| 男性 | 75.5 | 69.2 | ||||||

| 女性 | 81.2 | 59.0 | ||||||

| 瘤体直径 | 9.03 | 0.003 | 2.84 | 0.29~27.53 | 0.568 | |||

| ≥5 cm | 68.8 | 54.3 | ||||||

| < 5 cm | 95.5 | 89.5 | ||||||

| 肿瘤位置 | 0.58 | 0.900 | ||||||

| 前壁 | 83.7 | 73.2 | ||||||

| 侧壁 | 81.4 | 74.6 | ||||||

| 后壁 | 87.5 | 58.3 | ||||||

| 全周 | 75.0 | 75.0 | ||||||

| 肿瘤部位 | 3.70 | 0.054 | 0.30 | 0.08~1.22 | 0.225 | |||

| 直肠 | 84.5 | 71.3 | ||||||

| 结肠 | 46.7 | 46.7 | ||||||

| 累及其他器官 | 2.18 | 0.140 | ||||||

| 是 | 61.5 | 46.2 | ||||||

| 否 | 81.9 | 71.4 | ||||||

| 术前RDW | 8.17 | 0.004 | 0.21 | 0.06~0.72 | 0.014 | |||

| ≥13% | 66.4 | 52.2 | ||||||

| < 13% | 96.0 | 90.4 | ||||||

| 手术方式 | 0.05 | 0.945 | ||||||

| 局部切除 | 75.6 | 64.8 | ||||||

| 扩大切除 | 79.7 | 68.3 | ||||||

| 辅助治疗 | 0.24 | 0.626 | ||||||

| 是 | 85.0 | 69.5 | ||||||

| 否 | 73.7 | 64.5 | ||||||

| NIH分级 | 14.02 | < 0.01 | 15.92 | 2.11~120.32 | 0.007 | |||

| 极低/低 | 100.0 | 93.8 | ||||||

| 中/高 | 64.7 | 51.0 | ||||||

| 术后并发症 | 0.53 | 0.468 | ||||||

| 有 | 81.3 | 69.6 | ||||||

| 无 | 76.9 | 65.9 | ||||||

| 注 GIST:胃肠道间质瘤(gastrointestinal stromal tumor);DFS:无瘤生存期(disease free survival);RDW:术前红细胞分布宽度(red blood cell distribution width);NIH:美国国立卫生研究院(National Institutes of Health) | ||||||||

GIST可起源于全消化道,主要发生于胃(56.4%)及小肠(32.7%),仅5.9%发生于结直肠[4]。结直肠GIST发病罕见且生物学行为复杂,故其临床特征及预后因素尚未充分阐明。结直肠GIST对放化疗均不敏感,外科切除仍是其主要疗法。手术方式大致分为局部切除术及根治性切除术,由于极少发生淋巴结转移,R0切除是手术首要目标。Hawkins等[5]纳入333例肛管直肠GIST患者,发现根治切除组与局部切除组5年生存率比较,差异无统计学意义(P=0.71),且本研究发现2种术式的5年DFS率比较,差异无统计学意义(P=0.973)。以上说明,局部切除术可提供与根治术相当的生存获益,但局部切除术创伤小恢复快,加之患者直肠肛门功能保留可显著提高术后生活质量,故局部切除术是结直肠GIST的首选术式。但由于结直肠GIST位置特殊,瘤体较大或侵犯周围重要脏器时通常需要接受根治性切除术,具体术式的选择仍需更大样本量的研究进一步探讨。即使肿瘤可获得完整切除,术后复发率仍高达50%[6]。甲磺酸伊马替尼的出现改变了GIST治疗模式。既往研究发现,伊马替尼可显著改善GIST预后且术前用药可有效缩小瘤体和提高R0切除率[7-9]。本研究中术前评估难以达到R0切除的患者接受新辅助治疗,治疗后肿瘤降期满意均获得R0切除;术后接受伊马替尼辅助治疗的患者3年及5年DFS率均提高。手术切除联合伊马替尼靶向治疗已成为结直肠GIST的标准治疗方案[10]。

尽管结直肠GIST发病罕见,但其比胃间质瘤危险度高疗效差,故明确预后影响因素对临床诊治有重要意义[11-12]。目前临床主要采用2008年改良版NIH分级系统对GIST进行危险度评估。相关研究表明,肿瘤越大、NIH分级越高,GIST的预后越差[5, 13]。本研究单因素分析提示,NIH危险度分级越高DFS越短。进一步多因素分析证实,NIH危险度分级是预后的独立危险因素(P=0.007),与既往研究相符相似[5, 13]。尽管单因素分析发现,瘤体直径≥5 cm是DFS相关危险因素(P=0.003),但多因素分析并未证实其是独立危险因素,推测由于结直肠GIST发病率低,本组为单中心小样本研究且患者瘤体偏小(均值3.9 cm)导致结果产生偏倚。

炎症反应在肿瘤的发生和发展中起重要作用。炎症因子通过抑制细胞凋亡促进肿瘤侵袭及血管形成。研究表明,肿瘤患者预后与全身炎症状态密切相关[13-14]。RDW是反映红细胞体积异质性的参数,既往常用于贫血病诊断。近年来研究发现,RDW与多项机体炎症指标呈正相关(r=0.18~0.21, 均P < 0.01)[15]。尽管目前RDW与炎症状态发生和发展的相关机制尚未明确,但高水平的RDW被认为是由慢性炎症及营养不良造成[16-17]。大量研究证实,术前高水平RDW与肺癌[18]、胃癌[19]、肝癌[20]和乳腺癌[21]等癌症的不良预后相关[22]。研究发现,全身炎症反应指数可作为GIST复发的预测因素[23],但RDW是否对GIST预后产生不良影响尚未达成共识。本研究单因素分析发现,不同术前RDW水平的患者DFS比较,差异具有统计学意义(P=0.004)。多因素分析提示,术前RDW是结直肠GIST独立预后因素(P=0.014)。此项血液学资料简便易获取,有望作为结直肠GIST价廉高效的预后指标之一,但尚需大样本前瞻性随机临床试验进一步证实。

本研究存在一定的局限性:(1)本研究为回顾性研究,选择研究对象时难以避免选择性偏倚;(2)单中心小样本研究可能存在统计学偏差,仍需多中心大样本前瞻性研究进一步证实以上结果。尽管存在欠缺,但据笔者所知此为现今国内结直肠GIST最大样本量的研究,可为临床诊疗提供一定参考。

本研究总结了结直肠GIST的临床病理特征,阐明手术切除联合伊马替尼靶向治疗为结直肠GIST的标准治疗方案,证实NIH危险度分级与术前RDW均是DFS独立危险因素(均P < 0.05),发现术前RDW对患者预后有一定预测价值。临床医师应对结直肠GIST患者进行严密评估,结合临床特征及预后因素制定诊疗方案,使更多结直肠GIST患者受益。

| [1] |

Kaneko M, Emoto S, Murono K, et al. Neoadjuvant imatinib therapy in rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors[J]. Surg Today, 2019, 49(6): 460-466. DOI:10.1007/s00595-018-1737-5 |

| [2] |

Choi H, Charnsangavej C, Faria S C, et al. Correlation of computed tomography and positron emission tomography in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor treated at a single institution with imatinib mesylate: proposal of new computed tomography response criteria[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2007, 25(13): 1753-1759. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3049 |

| [3] |

Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor[J]. Hum Pathol, 2008, 39(10): 1411-1419. DOI:10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.025 |

| [4] |

李亚鸿, 解红霞, 王华, 等. 内蒙古地区胃肠道间质瘤804例临床数据分析[J]. 实用肿瘤杂志, 2021, 36(2): 118-124. |

| [5] |

Hawkins AT, Wells KO, Krishnamurty DM, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy and survival for large anorectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A national analysis of 333 cases[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2017, 24(5): 1195-1201. DOI:10.1245/s10434-016-5706-1 |

| [6] |

Centonze D, Pulvirenti E, Pulvirenti D'urso A, et al. Local excision with adjuvant imatinib therapy for anorectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors[J]. Tech Coloproctol, 2013, 17(5): 571-574. DOI:10.1007/s10151-013-0976-0 |

| [7] |

Tang S, Yin Y, Shen C, et al. Preoperative imatinib mesylate (IM) for huge gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST)[J]. World J Surg Oncol, 2017, 15(1): 79. DOI:10.1186/s12957-017-1143-2 |

| [8] |

Kurokawa Y, Yang HK, Cho H, et al. Phase Ⅱ study of neoadjuvant imatinib in large gastrointestinal stromal tumours of the stomach[J]. Br J Cancer, 2017, 117(1): 25-32. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2017.144 |

| [9] |

Jakhetiya A, Garg PK, Prakash G, et al. Targeted therapy of gastrointestinal stromal tumours[J]. World J Gastrointest Surg, 2016, 8(5): 345-352. DOI:10.4240/wjgs.v8.i5.345 |

| [10] |

Del Rio P, Bertocchi E, Dell'abate P, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a single center retrospective 15 years study[J]. Ann Ital Chir, 2016, 87: 426-432. |

| [11] |

麦日耶木姑丽·艾山, 陈志芬. 胃肠间质瘤的临床特征及其内镜下治疗的疗效研究[J]. 实用肿瘤杂志, 2020, 35(6): 559-563. DOI:10.13267/j.cnki.syzlzz.2020.06.016 |

| [12] |

Parab TM, Derogatis MJ, Boaz AM, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a comprehensive review[J]. J Gastrointest Oncol, 2019, 10(1): 144-154. |

| [13] |

Gold JS, Gönen M, Gutiérrez A, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for recurrence-free survival after complete surgical resection of localised primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a retrospective analysis[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2009, 10(11): 1045-1052. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70242-6 |

| [14] |

Dupré A, Malik HZ. Inflammation and cancer: What a surgical oncologist should know[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2018, 44(5): 566-570. DOI:10.1016/j.ejso.2018.02.209 |

| [15] |

Lippi G, Targher G, Montagnana M, et al. Relation between red blood cell distribution width and inflammatory biomarkers in a large cohort of unselected outpatients[J]. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2009, 133(4): 628-632. DOI:10.5858/133.4.628 |

| [16] |

Patel KV, Ferrucci L, Ershler WB, et al. Red blood cell distribution width and the risk of death in middle-aged and older adults[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2009, 169(5): 515-523. DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.11 |

| [17] |

Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Woodman RC, et al. Proinflammatory state and circulating erythropoietin in persons with and without anemia[J]. Am J Med, 2005, 118(11): 1288. |

| [18] |

Koma Y, Onishi A, Matsuoka H, et al. Increased red blood cell distribution width associates with cancer stage and prognosis in patients with lung cancer[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(11): e80240. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0080240 |

| [19] |

Cheng S, Han F, Wang Y, et al. The red distribution width and the platelet distribution width as prognostic predictors in gastric cancer[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2017, 17(1): 163. DOI:10.1186/s12876-017-0685-7 |

| [20] |

Goyal H, Hu ZD. Prognostic value of red blood cell distribution width in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2017, 5(13): 271. DOI:10.21037/atm.2017.06.30 |

| [21] |

Seretis C, Seretis F, Lagoudianakis E, et al. Is red cell distribution width a novel biomarker of breast cancer activity? Data from a pilot study[J]. J Clin Med Res, 2013, 5(2): 121-126. |

| [22] |

Montagnana M, Danese E. Red cell distribution width and cancer[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2016, 4(20): 399. DOI:10.21037/atm.2016.10.50 |

| [23] |

Yilmaz A, Mirili C, Bilici M, et al. A novel predictor in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Systemic immune-inflammation index (SⅡ)[J]. J BUON, 2019, 24(5): 2127-2135. |

2022, Vol. 37

2022, Vol. 37