文章信息

- 倪文, 王羲, 王奇胜, 段俊伟

- Ni Wen, Wang Xi, Wang Qisheng, Duan Junwei

- c-Met与GPC1在非小细胞肺癌中的表达及预后意义

- Expression of c-Met and glypican1 in non-small-cell lung cancer and its prognostic significance

- 实用肿瘤杂志, 2020, 35(6): 506-510

- Journal of Practical Oncology, 2020, 35(6): 506-510

-

作者简介

- 倪文(1986-), 男,湖北汉川人,主治医师,从事急诊医学临床研究.

-

通信作者

- 段俊伟, E-mail: 378939321@qq.com

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2019-06-03

2. 汉川市人民医院肿瘤科,湖北 汉川 431600

2. Oncology Department, Hanchuan People's Hospital, Hanchuan 431600, China

肺癌已成为全球发病率最高的恶性肿瘤,其中 > 90%的患者被诊断为非小细胞肺癌(non-small-cell lung cancer, NSCLC)[1],患者预后不佳,5年生存率较低[2]。肝细胞生长因子受体(hepatocyte growth factor receptor, c-Met)是一种由原癌基因c-Met编码的蛋白产物[3]。c-Met作为一种跨膜受体蛋白,已经发现在胃癌[4]、大肠癌[5]和胰腺癌[6]中过表达,与肿瘤的恶性增殖和远处转移密切相关。磷脂酰肌醇蛋白聚糖1(glypican 1,GPC1)是一种磷脂酰肌醇蛋白聚糖,是肝素结合生长因子的共受体。研究发现,GPC1在乳腺癌[7]、子宫颈癌[8]以及脑胶质瘤[9]中存在异常表达。本研究拟分析c-Met和GPC1在NSCLC组织及其癌旁组织中的表达情况,并分析其表达与患者临床病理资料之间的关系,对患者进行为期5年的预后随访。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料收集本院于2012年1月至2014年1月确诊治疗的234例NSCLC患者肿瘤组织及癌旁组织。其中男性160例,女性74例;年龄45~85岁,平均年龄65岁;< 60岁77例,≥60岁157例。有吸烟史99例,无吸烟史135例。临床分期:Ⅰ~Ⅱ期和Ⅲ~Ⅳ期分别有108例和126例;病理类型:鳞癌、腺癌、腺鳞癌、大细胞癌和其他类型分别有94、104、6、10和20例,104例腺癌中含52例混合型腺癌、39例腺泡型腺癌、7例乳头状腺癌及6例实性腺癌;分化程度:低、中和高分化分别有86、102及46例。有和无淋巴结转移病例分别为110和124例。按照肿瘤部位分类有120例中央型和114例周围型。所有患者均采用电话随访5年进行预后统计。患者及家属均签署知情同意书。排除标准:临床资料不完整以及严重肝、肾脏器功能不全者。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 试剂兔抗人c-Met单抗购自上海善然生物科技有限公司。兔抗人GPC1单抗购自北京鼎国昌盛生物技术有限责任公司。DAB显色剂购自上海烜雅生物科技有限公司。苏木精购自上海宝曼生物科技有限公司。c-Met二抗购自上海北诺生物科技有限公司。GPC1二抗购自上海钰博生物科技有限公司。

1.2.2 免疫组织化学染色将肿瘤组织和癌旁组织分别进行石蜡包埋并切片,脱蜡水化后清洗切片。加入阻断液后封闭处理,分别加入c-Met一抗(1:100稀释)和GPC1一抗(1:700稀释)溶液,4℃孵育24 h后清洗,加入对应的二抗溶液孵育30 min后清洗,链霉菌抗生素蛋白-过氧化物酶溶液室温孵育30 min后再次清洗,DAB显色剂进行显色处理后清洗,苏木精对比染色后封固,显微镜下观察。

免疫组织化学实验结果评定[10]按染色深浅度积分和染色细胞阳性率评分。染色深浅度积分:0分为无染色,1分为浅染色,2分为棕黄色染色,3分为深棕黄色染色。染色细胞阳性率评分:0分为没有阳性细胞,1分为 < 10%的阳性细胞,2分为10%~50%的阳性细胞,3分为 > 50%~100%的阳性细胞。将上述2种积分相加,< 4分为阴性表达,≥4分为阳性表达。

1.3 统计学分析采用SPSS21.0软件进行统计学分析。计量资料采用t检验。计数资料采用χ2检验。Spearman进行相关性分析。Kaplan-Meier(K-M)法进行预后生存分析。以P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 肺癌组织中c-Met和GPC1的表达c-Met阳性表达主要在肿瘤细胞胞质和胞膜。c-Met在肺癌组织和癌旁组织中的表达阳性率分别为68.0%(159/234)和8.6%(20/234),差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。GPC1阳性表达主要在肿瘤细胞胞膜。GPC1在肺癌组织和癌旁组织中的表达阳性率分别为79.1%(185/234)和20.9%(49/234),差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。

2.2 肺癌组织中c-Met和GPC1表达与患者临床病理资料的关系在肺癌组织中,c-Met阳性表达在NSCLC患者的临床分期、淋巴结转移和分化程度方面差异均具有统计学意义(均P < 0.05);GPC1阳性表达在NSCLC患者的临床分期和淋巴结转移方面比较,差异均具有统计学意义(均P < 0.05);两者的阳性表达在患者的性别、年龄、是否吸烟、肿瘤组织病理类型及肿瘤部位方面比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P > 0.05,表 1)。

| 临床病理特征 | 例数 | c-Met | GPC1 | |||||

| 阳性(例,%) | χ2值 | P值 | 阳性(例,%) | χ2值 | P值 | |||

| 性别 | 0.128 | 0.775 | 0.794 | 0.391 | ||||

| 男性 | 160 | 117(73.1) | 117(73.1) | |||||

| 女性 | 74 | 42(56.8) | 68(91.9) | |||||

| 年龄 | 0.015 | 0.947 | 0.088 | 0.796 | ||||

| < 60岁 | 91 | 53(58.2) | 66(72.5) | |||||

| ≥60岁 | 143 | 106(74.1) | 119(83.2) | |||||

| 吸烟 | 0.211 | 0.529 | 0.326 | 0.627 | ||||

| 有 | 135 | 101(74.8) | 118(87.4) | |||||

| 无 | 99 | 58(58.6) | 67(67.7) | |||||

| 病理类型 | 0.377 | 0.549 | 0.203 | 0.715 | ||||

| 鳞癌 | 94 | 51(54.3) | 78(83.0) | |||||

| 腺癌 | 104 | 89(85.6) | 84(80.8) | |||||

| 腺鳞癌 | 6 | 3(50.0) | 2(33.3) | |||||

| 大细胞癌 | 10 | 4(40.0) | 7(70.0) | |||||

| 其他类型 | 20 | 12(60.0) | 14(70.0) | |||||

| 临床分期 | 3.138 | 0.034 | 10.016 | 0.003 | ||||

| Ⅰ~Ⅱ | 108 | 41(38.0) | 66(61.1) | |||||

| Ⅲ~Ⅳ | 126 | 118(93.7) | 119(94.4) | |||||

| 淋巴结转移 | 12.345 | 0.001 | 22.018 | < 0.01 | ||||

| 有 | 160 | 127(79.4) | 146(91.3) | |||||

| 无 | 74 | 32(43.2) | 39(52.7) | |||||

| 分化程度 | 8.016 | 0.017 | 0.067 | 0.805 | ||||

| 低 | 86 | 80(93.0) | 67(77.9) | |||||

| 中 | 102 | 73(71.6) | 84(82.4) | |||||

| 高 | 46 | 6(13.0) | 34(73.9) | |||||

| 肿瘤部位 | 0.386 | 0.642 | 0.234 | 0.703 | ||||

| 中央型 | 120 | 72(60.0) | 92(76.7) | |||||

| 周围型 | 114 | 87(76.3) | 93(81.6) | |||||

| 注 c-Met:肝细胞生长因子受体(hepatocyte growth factor receptor);GPC1:磷脂酰肌醇蛋白聚糖1(glypican 1) | ||||||||

在NSCLC患者的肿瘤组织中,c-Met蛋白和GPC1蛋白的表达呈正相关(r=0.706,P < 0.01,表 2)。

| c-Met | GPC1 | 合计 | r值 | P值 | |

| 阳性 | 阴性 | ||||

| 阳性 | 134 | 25 | 159 | 0.706 | < 0.01 |

| 阴性 | 51 | 24 | 75 | ||

| 合计 | 185 | 49 | 234 | ||

| 注 c-Met:肝细胞生长因子受体(hepatocyte growth factor receptor);GPC1:磷脂酰肌醇蛋白聚糖1(glypican 1) | |||||

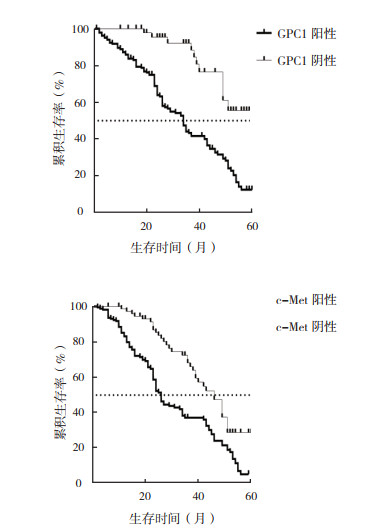

对所有纳入研究的患者进行为期5年的预后随访。GPC1阳性患者的5年生存率低于GPC1阴性患者,差异具有统计学意义(12.6% vs 56.3%,χ2=22.58,P < 0.01)。c-Met阳性患者的5年生存率低于c-Met阴性患者,差异具有统计学意义(5.3% vs 28.5%,χ2=17.84,P < 0.01;图 1)。

|

| 图 1 GPC1和c-Met阳性和阴性表达NSCLC患者总生存曲线 Fig.1 Overall survival curves of NSCLC patients with positive and negative expression of GPC1 and c-Met |

对上述多个变量进行回归分析发现,c-Met阳性表达、GPC1阳性表达、NSCLC临床分期以及淋巴结转移是NSCLC患者生存时间的主要影响因素(均P < 0.01, 表 3)。

| 因素 | B | S.E. | P值 | 95%CI |

| 性别 | 0.125 | 0.012 | 0.523 | 0.124 5~1.056 7 |

| 年龄 | 0.201 | 0.032 | 0.425 | 0.053 6~1.235 3 |

| 吸烟 | 0.142 | 0.052 | 0.325 | 0.020 5~1.325 0 |

| 病理类型 | 0.132 | 0.086 | 0.625 | 0.201 5~1.523 6 |

| 临床分期 | 0.801 | 0.115 | < 0.01 | 0.578 1~1.021 8 |

| 淋巴结转移 | 0.879 | 0.152 | < 0.01 | 0.513 4~1.046 8 |

| 分化程度 | 0.230 | 0.023 | 0.325 | 0.125 3~1.625 6 |

| 肿瘤部位 | 0.201 | 0.015 | 0.852 | 0.230 5~1.425 6 |

| c-Met | 0.791 | 0.117 | < 0.01 | 1.094 5~1.964 3 |

| GPC1 | 0.679 | 0.123 | < 0.01 | 1.071 6~1.987 2 |

目前已知的所有恶性肿瘤中,肺癌的发病率和死亡率均居首,其中以NSCLC最多见。NSCLC在临床病理类型中主要类型有2类,即腺癌和鳞癌[11]。传统的放化疗方法虽能暂时缓解患者的痛苦,但预后较差,5年生存率 < 15%[12]。

目前学术界普遍认为肿瘤新生血管生成是肿瘤生长和发展的基础,新生血管生成则是由多种因素综合长期影响的结果[13-15]。近年来研究发现,由原癌基因c-Met编码的跨膜受体蛋白c-Met蛋白能够刺激内皮细胞的分化和迁移等过程,最终可以有效促进新生血管生成[16]。研究显示,NSCLC患者肿瘤组织中c-Met过表达,超出正常组织近3倍表达量[17];肺癌中c-Met的表达与肺癌的临床分期有关[18]。c-Met的表达量与肺癌的分化程度存在关联,分化程度越高,表达量越高[19]。多项研究结果均表明,c-Met的表达参与NSCLC的发生和发展过程[20-21]。GPC1是一种磷脂酰肌醇蛋白聚糖,通过糖基磷脂酰肌醇附着于细胞膜表面[22]。在多种肿瘤细胞上呈过表达状态,如乳腺癌、子宫颈癌以及脑胶质瘤等。GPC1的过表达与肿瘤细胞的增殖、转移及新生血管生成之间存在密切的关联性[23]。在肿瘤患者的外周血血清中可以检测到GPC1阳性的外泌体[24]。胰腺癌组织中GPC1过表达,可以作为胰腺癌总生存率的独立预后指标[25]。

本研究结果显示,在NSCLC组织中,c-Met和GPC1蛋白均过表达,与以往研究结果一致[26-28]。相关性分析发现,在NSCLC组织中c-Met和GPC1蛋白的表达呈正相关(r=0.706,P < 0.01),提示两者可能发挥协同作用,共同促进NSCLC的发生和发展过程。c-Met与GPC1在NSCLC组织中的阳性表达与患者的临床分期和淋巴结转移有关。生存分析结果发现,c-Met阴性表达和GPC1阴性表达患者的5年生存率均高于对应阳性表达患者。通过预后影响因素分析发现,c-Met阳性表达、GPC1阳性表达、NSCLC临床分析以及淋巴结转移是NSCLC患者生存时间的主要影响因素(均P < 0.01)。

综上所述,NSCLC患者肿瘤组织中c-Met和GPC1阳性表达且预后不良,两者表达呈正相关,提示可能共同作用、协同促进NSCLC的发生和发展。本研究结论可能为NSCLC患者的临床靶向治疗提供参考依据。

| [1] |

Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Nature, 2018, 553(7689): 446-454. DOI:10.1038/nature25183 |

| [2] |

Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL, et al. Lung cancer: current therapies and new targeted treatments[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389(10066): 299-311. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30958-8 |

| [3] |

Ho-Yen CM, Jones JL, Kermorgant S. The clinical and functional significance of c-Met in breast cancer: a review[J]. Breast Cancer Res, 2015, 17(1): 52. DOI:10.1186/s13058-015-0547-6 |

| [4] |

Yao JF, Li XJ, Yan LK, et al. Role of HGF/c-Met in the treatment of colorectal cancer with liver metastasis[J]. J Biochem Mol Toxicol, 2019, 11(20): e22316. |

| [5] |

Bouattour M, Raymond E, Qin S, et al. Recent developments of c-Met as a therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2018, 67(3): 1132-1149. DOI:10.1002/hep.29496 |

| [6] |

Herreros-Villanueva M, Bujanda L. Glypican-1 in exosomes as biomarker for early detection of pancreatic cancer[J]. Ann Transl Med, 2016, 4(4): 64. |

| [7] |

Li J, Li B, Ren C, et al. The clinical significance of circulating GPC1 positive exosomes and its regulative miRNAs in colon cancer patients[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(60): 101189-101202. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.20516 |

| [8] |

Frampton AE, Prado MM, López-Jiménez E, et al. Glypican-1 is enriched in circulating-exosomes in pancreatic cancer and correlates with tumor burden[J]. Oncotarget, 2018, 9(27): 19006-19013. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.24873 |

| [9] |

Li J, Chen Y, Guo X, et al. GPC1 exosome and its regulatory miRNAs are specific markers for the detection and target therapy of colorectal cancer[J]. J Cell Mol Med, 2017, 21(5): 838-847. DOI:10.1111/jcmm.12941 |

| [10] |

Dammeijer F, Lievense LA, Veerman GD, et al. Efficacy of tumor vaccines and cellular immunotherapies in non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2016, 34(26): 3204-3212. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3955 |

| [11] |

Bahrami A, Shahidsales S, Khazaei M, et al. C-Met as a potential target for the treatment of gastrointestinal cancer: Current status and future perspectives[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2017, 232(10): 2657-2673. DOI:10.1002/jcp.25794 |

| [12] |

Melo SA, Luecke LB, Kahlert C, et al. Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer[J]. Nature, 2015, 523(7559): 177-182. DOI:10.1038/nature14581 |

| [13] |

Verrier ER, Colpitts CC, Bach C, et al. A targeted functional RNA interference screen uncovers glypican 5 as an entry factor for hepatitis B and D viruses[J]. Hepatology, 2016, 63(1): 35-48. DOI:10.1002/hep.28013 |

| [14] |

Hellmann MD, Nathanson T, Rizvi H, et al. Genomic features of response to combination immunotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. Cancer Cell, 2018, 33(5): 843-852. DOI:10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.018 |

| [15] |

Ng CS, Zhao ZR, Lau RW. Tailored therapy for stage Ⅰ non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2017, 35(3): 268-270. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4718 |

| [16] |

Harada E, Serada S, Fujimoto M, et al. Glypican-1 targeted antibody-based therapy induces preclinical antitumor activity against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(15): 24741-24752. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.15799 |

| [17] |

Zhou CY, Dong YP, Sun X, et al. High levels of serum glypican-1 indicate poor prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma[J]. Cancer Med, 2018, 7(11): 5525-5533. DOI:10.1002/cam4.1833 |

| [18] |

Wu YL, Soo RA, Locatelli G, et al. Does c-Met remain a rational target for therapy in patients with EGFR TKI-resistant non-small cell lung cancer?[J]. Cancer Treat Rev, 2017, 61(22): 70-81. |

| [19] |

Marona P, Górka J, Kotlinowski J, et al. C-Met as a key factor responsible for sustaining undifferentiated phenotype and therapy resistance in renal carcinomas[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(3): E272. DOI:10.3390/cells8030272 |

| [20] |

Gao W, Kim H, Feng M, et al. Inactivation of Wnt signaling by a human antibody that recognizes the heparan sulfate chains of glypican-3 for liver cancer therapy[J]. Hepatology, 2014, 60(2): 576-587. DOI:10.1002/hep.26996 |

| [21] |

Zhou F, Shang W, Yu X, et al. Glypican-3: A promising biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and treatment[J]. Med Res Rev, 2018, 38(2): 741-767. DOI:10.1002/med.21455 |

| [22] |

Fu J, Wang H. Precision diagnosis and treatment of liver cancer in China[J]. Cancer Lett, 2018, 412(20): 283-288. |

| [23] |

Yang H, Fan HX, et al. Relationship between contrast-enhanced CT and clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Oncol Res Treat, 2017, 40(9): 516-522. DOI:10.1159/000472256 |

| [24] |

Hatam LJ, Devoti JA, Rosenthal DW, et al. Immune suppression in premalignant respiratory papillomas: enriched functional CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and PD-1/PD-L1/L2 expression[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2012, 18(7): 1925-1935. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2941 |

| [25] |

Duan L, Hu XQ, Feng DY, et al. GPC-1 may serve as a predictor of perineural invasion and a prognosticator of survival in pancreatic cancer[J]. Asian J Surg, 2013, 36(1): 7-12. DOI:10.1016/j.asjsur.2012.08.001 |

| [26] |

Xu Y, Fan Y. Responses to crizotinib can occur in c-Met overexpressing nonsmall cell lung cancer after developing EGFR-TKI resistance[J]. Cancer Biol Ther, 2019, 20(2): 145-149. DOI:10.1080/15384047.2018.1523851 |

| [27] |

宋启斌, 胡胜. EGFR突变与非小细胞肺癌[J]. 中国肿瘤, 2007, 16(11): 910-914. |

| [28] |

袁世洋, 彭赖水, 谢军平, 等. ddPCR检测NSCLC患者血液EGFR基因突变准确性的Meta分析[J]. 中国肿瘤, 2019, 28(6): 461-469. |

2020, Vol. 35

2020, Vol. 35