文章信息

- 向瑶, 周伟弘, 王桃丽, 王俊普

- Xiang Yao, Zhou Weihong, Wang Taoli, Wang Junpu

- 结肠腺癌免疫预后基因的开发与验证

- Development and verifi cation of immune prognostic genes in colon adenocarcinoma

- 实用肿瘤杂志, 2022, 37(2): 163-170

- Journal of Practical Oncology, 2022, 37(2): 163-170

-

通信作者

- 王俊普,E-mail: wang-jp2013@csu.edu.cn

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2021-02-20

2. 株洲市中心医院病理科, 湖南 株洲 412007;

3. 中南大学基础医学院病理学系, 湖南 长沙 410013

2. Department of Pathology, Zhuzhou Central Hospital, Zhuzhou 412007, China;

3. Department of Pathology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Central South University, Changsha 410013, China

结肠腺癌(colon adenocarcinoma,COAD)是起源于结肠腺上皮的恶性肿瘤,是结肠肿瘤中最常见的病理类型。COAD是第三大常见的恶性肿瘤,据国际癌症研究机构(International Agency for Research on Cancer,IARC)统计,截至2018年,全世界结肠癌新发病例数为1 096 601例,发生率约为6.1%,死亡551 269例,死亡率约为5.8%[1]。在中国,结肠癌的发生率及死亡率居第五位,是癌症死亡的主要原因之一,严重危险人民生命健康,给社会经济造成极大负担[2-3]。内镜、手术局部切除术、术前放化疗、局部区域和转移性疾病的广泛手术、转移灶的局部消融治疗以及姑息化疗促使部分结肠癌患者从中受益,但手术治疗及化疗治疗的不良反应使结肠癌患者生活质量下降,并且部分不能耐受手术和放化疗的患者预后仍不乐观[4-5]。近年来,随着对肿瘤发展和免疫系统研究的不断深入,利用免疫系统建立有效的抗肿瘤反应的治疗迅速发展。肿瘤免疫治疗作为一种安全且有效的新治疗手段给肿瘤治疗带来新希望[6-8]。本研究旨在探究COAD患者高表达的免疫基因对患者预后研究的价值,为临床诊断及免疫治疗提供潜在生物标志物及治疗靶点。

1 资料与方法 1.1 数据获取2020年10月1日通过R语言TCGAbiolinks包从癌症基因组图谱(The Cancer Genome Atlas,TCGA)数据库(https://cancergenome.nih.gov/)中获取完整的COAD患者临床信息及RNA表达数据(包括284个COAD组织样品及41个COAD癌旁正常组织样品)。2020年10月1日通过Immport数据库(https://www.immport.org/home)下载免疫基因数据。2020年10月3日通过基因本体论(Gene Ontology,GO)(http://geneontology.org/)和东京基因和基因组的百科全书(Tokyo Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes,KEGG)数据库(https://www.kegg.jp/)下载数据并分析免疫基因为潜在的调控机制。

1.2 统计学分析采用R 3.6.1软件(www.r-project.org)进行统计学分析。利用limma包进行差异分析,差异基因筛选标准:校正P≤0.05;|log2差异倍数(fold change,FC)|≥2。将差异基因与免疫基因取交集获得差异的免疫基因。利用R语言clusterProfiler包进行GO和KEGG功能富集分析。利用survival包及survminar包进行单变量Cox回归分析,进一步进行多变量Cox回归分析构建预后风险评分模型,利用Kaplan-Meier曲线验证,并绘制受试者操作特征(receiver operating characteristic,ROC)曲线评估模型的预测能力。

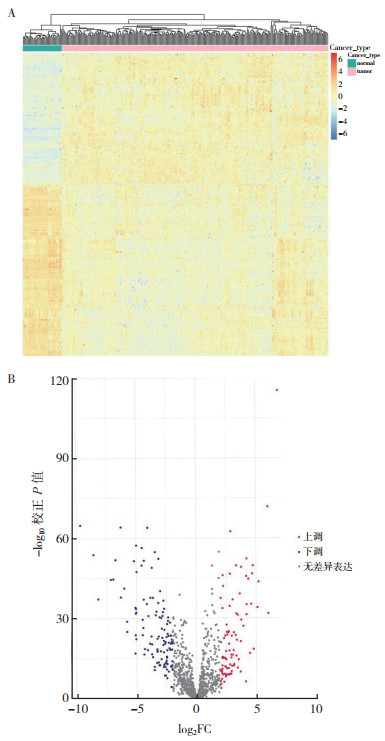

2 结果 2.1 COAD中差异表达免疫基因的筛选利用R语言中limma包并应用Wilcoxon秩和检验分析284个COAD组织样本和41个COAD癌旁组织样本,获得的差异基因与2 498个免疫基因取交集,得到207个差异表达的免疫基因(differential immune related gene,DEIRG)。其中,91个为上调的免疫基因,116个为下调的免疫基因(图 1A~1B)。

|

| 注 A:热图;B:火山图;FC:差异倍数(fold change) 图 1 结肠腺癌和癌旁组织中差异表达的免疫基因的热图和火山图 Fig.1 Heatmaps and volcano plots of differentially expressed immune genes in colon adenocarcinoma and paracancerous tissues |

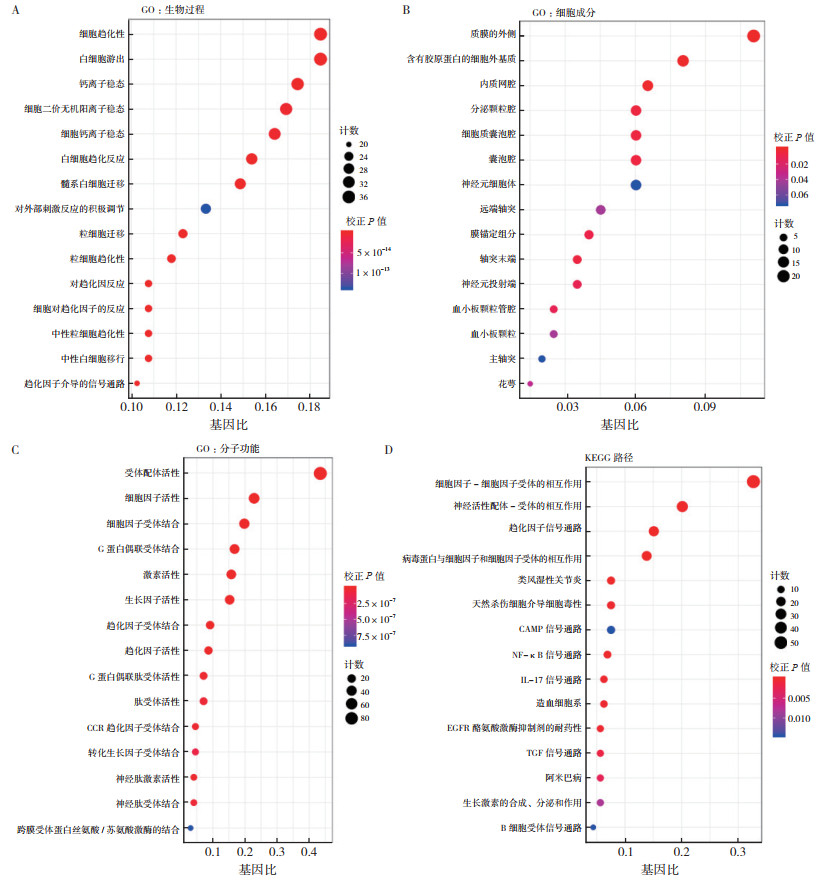

对207个差异表达的免疫基因进行GO和KEGG功能富集分析。GO包括生物过程(biological process,BP)、细胞成分(cellular component,CC)和分子功能(molecular function,MF)。结果显示,这些免疫基因在细胞因子-细胞因子受体相互作用及神经活性配体-受体相互作用的通路上富集(图 2A~2D)。

|

| 注 A:生物过程气泡图;B:细胞成分气泡图;C:分子功能气泡图;D:KEGG通路气泡图;CCR:C-C基序趋化因子受体(C-C motif chemokine receptor);CAMP:环腺苷酸(cyclic adenosine monophosphate);NF-kB:核转录因子kB亚基(nuclear factor kappa B subunit);IL-17:白介素17(interleukin 17);EGFR:表皮生长因子受体(epidermal growth factor receptor);TGF:转化生长因子(transforming growth factor) 图 2 COAD中差异表达的免疫基因的GO和KEGG富集分析 Fig.2 The enrichment analysis of GO and KEGG of the differentially expressed immune genes in COAD |

从TCGA数据库下载COAD患者完整的临床数据,提取生存时间、生存状态、性别、年龄、TNM分期和T分期等。筛除临床信息不完整及随访时间 < 30 d者,最终纳入245例建模。245例患者年龄31~88岁,中位年龄67岁;男性133例,女性112例。对COAD中207个差异表达的免疫基因进行单因素Cox回归分析,确定10个与患者总生存时间相关的免疫基因(均P < 0.05)。为确定预测的模型为最佳的预后模型,进一步将上述基因纳入多因素Cox回归分析中,从而构建精确预测预后的风险评分模型。多因素Cox回归分析结果显示,载脂蛋白12(lipocalin 12,LCN12)、嗜铬素A(chromogranin A,CHGA)、抑制素β亚基(inhibin subunit beta B,INHBB)、R3H域包含像(R3H domain containing like,R3HDML)和黑皮质素1受体(melanocortin 1 receptor,MC1R)5个免疫基因与预后独立相关(均P < 0.05),其中LCN12(HR=1.339,P=0.014)、INHBB(HR=1.221,P=0.030)、R3HDML(HR=1.288,P=0.033)及MC1R(HR=1.389,P=0.049)为高危DEIRG与患者的预后呈负相关;CHGA为低危DEIRG与患者的预后呈正相关(HR=0.893,P=0.028;表 1)。

| 基因 | coef | HR | 95%CI | P值 |

| LCN12 | 0.291 | 1.339 | 1.061~1.689 | 0.014 |

| CHGA | -0.113 | 0.893 | 0.807~0.988 | 0.028 |

| INHBB | 0.200 | 1.221 | 1.019~1.463 | 0.030 |

| R3HDML | 0.253 | 1.288 | 1.021~1.626 | 0.033 |

| MC1R | 0.328 | 1.389 | 1.002~1.925 | 0.049 |

| 注 coef:相关系数(correlation coefficient) | ||||

根据这5个免疫基因的表达量创建总生存时间预测风险评分公式,风险评分为各基因表达值与相关系数的乘积之和。加入年龄、性别、T分期及TNM分期等临床参数进行单因素和多因素Cox风险回归分析显示,年龄、TNM分期及风险评分与患者总生存相关,是COAD的独立预后指标(均P < 0.05,表 2)。

| 临床变量 | 单因素分析 | 多因素分析 | |||

| HR(95%CI) | P值 | HR(95%CI) | P值 | ||

| 年龄 | 1.043(1.010~1.078) | 0.011 | 1.054(1.016~1.094) | 0.005 | |

| 性别 | 1.925(0.904~4.099) | 0.089 | 1.675(0.705~3.977) | 0.243 | |

| TNM分期 | 2.534(1.186~5.415) | 0.016 | 2.838(1.243~6.481) | 0.013 | |

| T分期 | 6.223(0.845~45.820) | 0.075 | 3.017(0.390~23.298) | 0.290 | |

| 风险评分 | 1.587(1.160~2.173) | 0.004 | 1.670(1.143~2.440) | 0.008 | |

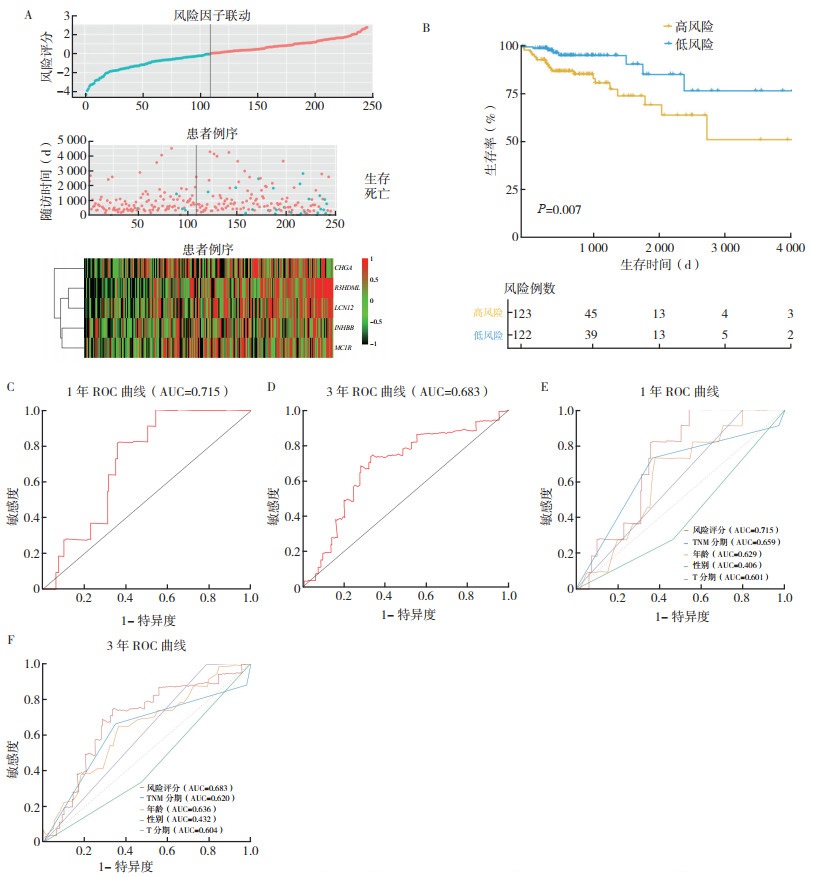

根据风险评分中位值将患者分为高风险组和低风险组。高风险组患者死亡率较高,表达高水平的高风险免疫基因(LCN12、INHBB、R3HDML和MC1R),表达低水平的低风险免疫基因(CHGA)。采用对数秩检验对该模型进行Kaplan-Meier分析显示,高风险组患者预后较差(P=0.007,图 3B)。高风险组1年和3年总生存率分别为76.2%和65.2%。预后风险模型中,风险评分预测1年和3年总生存的ROC曲线下面积(area under curve,AUC)分别为0.715和0.683(图 3C~3D)。临床病理特征TNM分期、年龄、性别及T分期预测1年总生存的ROC AUC为0.659、0.629、0.406和0.601,预测3年总生存的ROC AUC为0.620、0.636、0.432和0.604,均低于风险评分,具有更好的预测性能和准确度(图 3E~3F)。

|

| 注 A:高风险(红色)和低风险(蓝色)患者风险评分分布、生存状态及免疫基因表达的热图(红色代表免疫基因高表达,黑色代表免疫基因低表达);B:高风险和低风险患者生存曲线;C:免疫基因预后模型预测1年总生存的ROC曲线;D:免疫基因预后模型预测3年总生存的ROC曲线;E:风险评分和临床病理特征预测1年总生存的ROC曲线比较;F:风险评分和临床病理特征预测3年总生存的ROC曲线比较 图 3 高风险和低风险COAD患者预后风险模型 Fig.3 Prognostic risk model for high-risk and low-risk COAD patients |

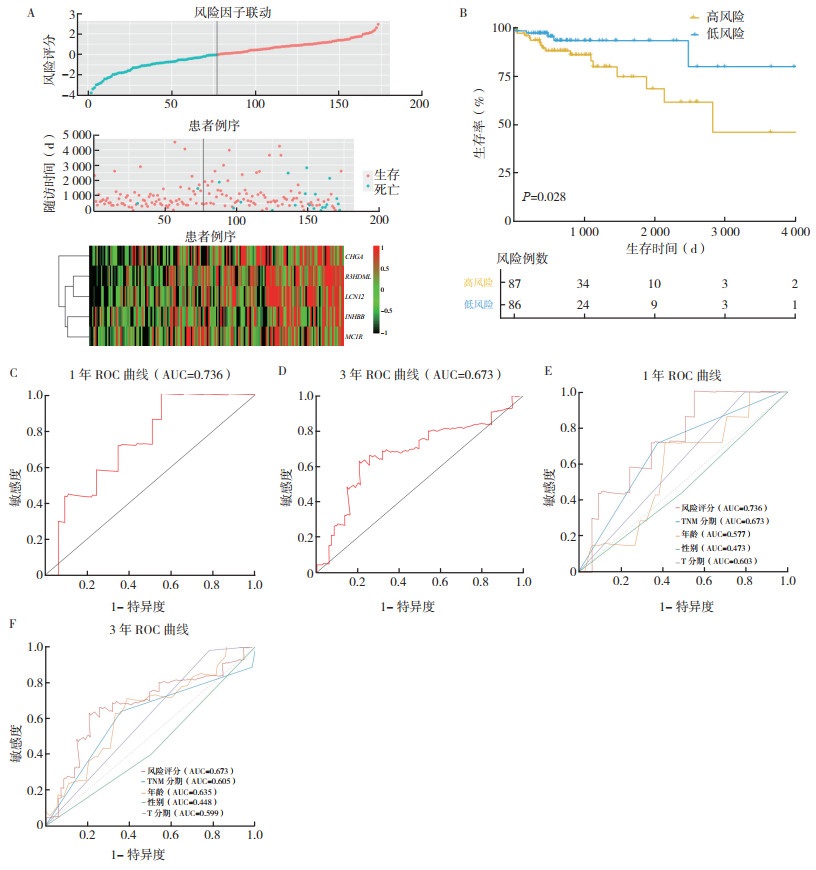

利用R语言caret包从344个COAD样本中,随机抽取172个样本为内部验证组。Kaplan-Meier生存曲线显示,高风险组患者较低风险组患者预后差(P=0.028,图 4B)。高风险组患者1年和3年总生存率分别为84.1%和74.8%。风险评分预测1年和3年总生存的ROC AUC分别为0.736和0.673(图 4C~4D)。TNM分期、年龄、性别及T分期预测1年总生存的ROC AUC分别为0.673、0.577、0.473和0.603,预测3年总生存的ROC AUC分别为0.605、0.635、0.448和0.599,均低于风险评分(图 4E~4F)。内部验证组与运用风险评分模型得到一致的生存分析结果。

|

| 注 A:高风险(红色)和低风险(蓝色)患者风险评分分布、生存状态及免疫基因表达的热图(红色代表免疫基因高表达,黑色代表免疫基因低表达);B:高风险和低风险患者生存曲线;C:免疫基因预后模型预测1年总生存的ROC曲线;D:免疫基因预后模型预测3年总生存的ROC曲线;E:风险评分和临床病理特征预测1年总生存的ROC曲线比较;F:风险评分和临床病理特征预测3年总生存的ROC曲线比较 图 4 内部验证高风险和低风险COAD患者预后风险模型 Fig.4 Internal validation of the prognostic risk model for high-risk and low-risk COAD patients |

近年来,COAD死亡率呈上升趋势,已位居癌症死亡的第二位,为世界范围内癌症相关死亡的重要原因之一[4]。在发达国家,通过筛查进行早期发现可提高COAD患者的5年总生存率,而在发展中国家,由于医疗水平落后,部分患者初次就诊时已为晚期,甚至出现远处转移,这使得COAD患者生存率下降[9-10]。因此,迫切需要解决针对COAD晚期患者开发更有效的治疗方法。在过去的几年中,由于免疫疗法成功地实现了对先前难以治疗实体瘤(如肺癌[11]、黑色素瘤[12-13]和肝癌[14])的长期持久反应,致使研究者们坚信免疫治疗的重要性及其治疗前景。肿瘤细胞随着免疫反应的发展而发展,通过改变甚至停止抗肿瘤免疫,致使免疫系统功能障碍[15]。这种免疫逃避机制会破坏内在发展的抗肿瘤免疫力,从而导致无法控制肿瘤的生长。因此,扭转肿瘤微环境中肿瘤诱导的免疫缺陷,恢复免疫正常化,已成为免疫治疗的基本准则[16-17]。

本研究利用生物信息学技术,筛选出在COAD癌和癌旁样本中差异表达的207个DEIRG,通过GO和KEGG富集DEIRG的分子通路,通过单因素和多因素Cox比例风险回归模型,鉴定出5个与患者总生存预后价值相关的免疫基因(LCN12、CHGA、INHBB、R3HDML和MC1R),并建立一个与免疫相关的基因标签以指导COAD患者的诊断与治疗。

CHGA是一种酸性糖蛋白,存在于内分泌细胞的分泌囊泡和胃肠道嗜镉细胞[18],在神经内分泌肿瘤的血液及组织样本中高表达,已成为神经内分泌肿瘤病理诊断的生物标志物[19]。与结肠正常黏膜比较,CHGA在结肠癌早期阶段的组织中表达下降,可用于结肠癌早期诊断[20]。在神经内分泌前列腺癌中,CHGA表达升高,增加肿瘤血管生成,从而促进癌症进程[21]。INHBB是一种蛋白质编码基因,参与转化生长因子-β(transforming growth factor-beta,TGF-β)家族成员的合成[22]。INHBB的高表达与口腔癌的局部淋巴结转移有关,并促进细胞的增殖和迁移[22]。INHBB在结直肠癌中过表达,且与侵袭深度、远距离转移和TNM分期呈正相关[23]。INHBB与TGF-β信号通路在结肠癌中的DNA损伤反应和DNA损伤修复密切相关[24],表明INHBB可能通过介导这些促癌途径及其下游靶点参与结直肠癌的调节[25]。MC1R是一种G蛋白偶联受体,在人类和小鼠的色素沉着中起关键作用[26]。研究发现,MC1R激活可防止黑色素瘤的发生[27]。R3HDML是含有R3H结构域的基因,最初通过肾脏微阵列芯片筛选获得的肾小球诱导基因[28]。研究表明,R3HDML对于骨骼肌发育和再生,特别是卫星细胞增殖和分化具有重要作用[29]。但MC1R、R3HDML及LCN12基因在COAD中的研究尚未报道。

COAD具有异质性,不同临床疗效的患者群体在基因表达上存在差异。本研究通过生物信息学方法鉴定的5个免疫预后基因和风险评分模型尚未见报道。本研究将为COAD的分子机制、预后的预测及免疫治疗提供新的思路。

| [1] |

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6): 394-424. DOI:10.3322/caac.21492 |

| [2] |

Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2016, 66(2): 115-132. DOI:10.3322/caac.21338 |

| [3] |

陈自喜, 张孟哲, 朱兆伟, 等. 结肠癌患者外周血microRNA-21、淋巴细胞亚群及炎性因子的相关性研究[J]. 实用肿瘤杂志, 2021, 36(4): 314-319. |

| [4] |

Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, et al. Colorectal cancer[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10207): 1467-1480. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32319-0 |

| [5] |

张丽娜, 孔祥兴, 李昕琳, 等. 结直肠癌pT4期诊断的难点及辅助诊断方案的研究进展[J]. 实用肿瘤杂志, 2021, 36(1): 6-10. |

| [6] |

Lohmueller J, Finn OJ. Current modalities in cancer immunotherapy: Immunomodulatory antibodies, CARs and vaccines[J]. Pharmacol Therapeut, 2017, 178(8): 31-47. |

| [7] |

Olson B, Li Y, Lin Y, et al. Mouse models for cancer immunotherapy research[J]. Cancer Discov, 2018, 8(11): 1358-1365. DOI:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0044 |

| [8] |

Zou W, Wolchok JD, Chen L. PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-1 pathway blockade for cancer therapy: Mechanisms, response biomarkers, and combinations[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2016, 8(328): 328rv324. |

| [9] |

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2017, 67(3): 177-193. DOI:10.3322/caac.21395 |

| [10] |

宋昕, 韩文莉, 王盼盼, 等. 食管鳞癌、贲门腺癌和结肠腺癌高频突变基因谱比较[J]. 实用肿瘤杂志, 2020, 35(5): 401-407. |

| [11] |

Iams WT, Porter J, Horn L. Immunotherapeutic approaches for small-cell lung cancer[J]. Nat Rev, Clin Oncol, 2020, 17(5): 300-312. DOI:10.1038/s41571-019-0316-z |

| [12] |

Sahin U, Oehm P, Derhovanessian E, et al. An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma[J]. Nature, 2020, 585(7823): 107-112. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2537-9 |

| [13] |

Grasso CS, Tsoi J, Onyshchenko M, et al. Conserved interferon-γ signaling drives clinical response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy in melanoma[J]. Cancer Cell, 2020, 38(4): 500-515. DOI:10.1016/j.ccell.2020.08.005 |

| [14] |

Greten TF, Mauda-Havakuk M, Heinrich B, et al. Combined locoregional-immunotherapy for liver cancer[J]. J Hepatol, 2019, 70(5): 999-1007. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.027 |

| [15] |

Andrews LP, Marciscano AE, Drake CG, et al. LAG3 (CD223) as a cancer immunotherapy target[J]. Immunol Rev, 2017, 276(1): 80-96. DOI:10.1111/imr.12519 |

| [16] |

Sanmamed MF, Chen L. A Paradigm shift in cancer immunotherapy: from enhancement to normalization[J]. Cell, 2018, 175(2): 313-326. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.035 |

| [17] |

Li Z, Song W, Rubinstein M, et al. Recent updates in cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive review and perspective of the 2018 China Cancer Immunotherapy Workshop in Beijing[J]. J Hematol Oncol, 2018, 11(1): 142. DOI:10.1186/s13045-018-0684-3 |

| [18] |

D'Amico MA, Ghinassi B, Izzicupo P, et al. Biological function and clinical relevance of chromogranin A and derived peptides[J]. Endocr Connect, 2014, 3(2): R45-54. DOI:10.1530/EC-14-0027 |

| [19] |

Mahata SK, Corti A. Chromogranin A and its fragments in cardiovascular, immunometabolic, and cancer regulation[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2019, 1455(1): 34-58. DOI:10.1111/nyas.14249 |

| [20] |

Zhang X, Zhang H, Shen B, et al. Chromogranin-A expression as a novel biomarker for early diagnosis of colon cancer patients[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(12): 2919. DOI:10.3390/ijms20122919 |

| [21] |

Wang Z, Zhao Y, An Z, et al. Molecular links between angiogenesis and neuroendocrine phenotypes in prostate cancer progression[J]. Front Oncol, 2019, 9(6): 1491. |

| [22] |

Namwanje M, Brown CW. Activins and inhibins: roles in development, physiology, and disease[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2016, 8(7): a021881. DOI:10.1101/cshperspect.a021881 |

| [23] |

Yuan J, Xie A, Cao Q, et al. INHBB is a novel prognostic biomarker associated with cancer-promoting pathways in colorectal cancer[J]. BioMed Res Int, 2020, 2020(10): 6909672. |

| [24] |

Zhao M, Mishra L, Deng CX. The role of TGF-β/SMAD4 signaling in cancer[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2018, 14(2): 111-123. DOI:10.7150/ijbs.23230 |

| [25] |

Calon A, Espinet E, Palomo-Ponce S, et al. Dependency of colorectal cancer on a TGF-β-driven program in stromal cells for metastasis initiation[J]. Cancer Cell, 2012, 22(5): 571-584. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.013 |

| [26] |

Jackson E, Heidl M, Imfeld D, et al. Discovery of a highly selective MC1R agonists pentapeptide to be used as a skin pigmentation enhancer and with potential anti-aging properties[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(24): 6143. DOI:10.3390/ijms20246143 |

| [27] |

Chen S, Zhu B, Yin C, et al. Palmitoylation-dependent activation of MC1R prevents melanomagenesis[J]. Nature, 2017, 549(7672): 399-403. DOI:10.1038/nature23887 |

| [28] |

Takemoto M, He L, Norlin J, et al. Large-scale identification of genes implicated in kidney glomerulus development and function[J]. EMBO, 2006, 25(5): 1160-1174. DOI:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601014 |

| [29] |

Sakamoto K, Furuichi Y, Yamamoto M, et al. R3hdml regulates satellite cell proliferation and differentiation[J]. EMBO Rep, 2019, 20(11): e47957. |

2022, Vol. 37

2022, Vol. 37